You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

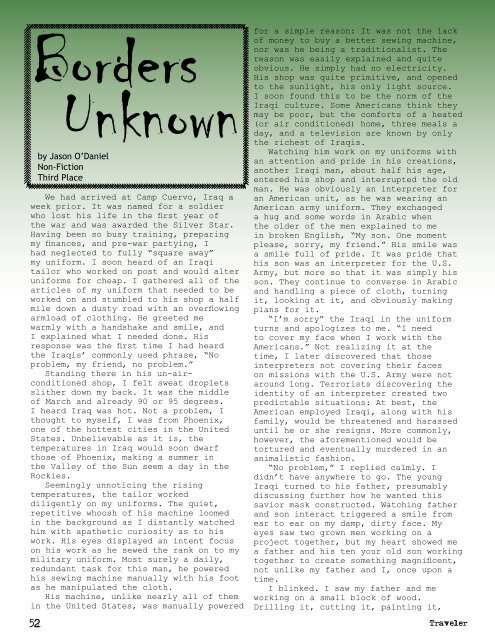

Borders<br />

Unknown<br />

by Jason O’Daniel<br />

Non-Fiction<br />

Third Place<br />

We had arrived at Camp Cuervo, Iraq a<br />

week prior. It was named for a soldier<br />

who lost his life in the first year of<br />

the war and was awarded the Silver Star.<br />

Having been so busy training, preparing<br />

my finances, and pre-war partying, I<br />

had neglected to fully “square away”<br />

my uniform. I soon heard of an Iraqi<br />

tailor who worked on post and would alter<br />

uniforms for cheap. I gathered all of the<br />

articles of my uniform that needed to be<br />

worked on and stumbled to his shop a half<br />

mile down a dusty road with an overflowing<br />

armload of clothing. He greeted me<br />

warmly with a handshake and smile, and<br />

I explained what I needed done. His<br />

response was the first time I had heard<br />

the Iraqis’ commonly used phrase, “No<br />

problem, my friend, no problem.”<br />

Standing there in his un-airconditioned<br />

shop, I felt sweat droplets<br />

slither down my back. It was the middle<br />

of March and already 90 or 95 degrees.<br />

I heard Iraq was hot. Not a problem, I<br />

thought to myself, I was from Phoenix,<br />

one of the hottest cities in the United<br />

States. Unbelievable as it is, the<br />

temperatures in Iraq would soon dwarf<br />

those of Phoenix, making a summer in<br />

the Valley of the Sun seem a day in the<br />

Rockies.<br />

Seemingly unnoticing the rising<br />

temperatures, the tailor worked<br />

diligently on my uniforms. The quiet,<br />

repetitive whoosh of his machine loomed<br />

in the background as I distantly watched<br />

him with apathetic curiosity as to his<br />

work. His eyes displayed an intent focus<br />

on his work as he sewed the rank on to my<br />

military uniform. Most surely a daily,<br />

redundant task for this man, he powered<br />

his sewing machine manually with his foot<br />

as he manipulated the cloth.<br />

His machine, unlike nearly all of them<br />

in the United States, was manually powered<br />

52<br />

for a simple reason: It was not the lack<br />

of money to buy a better sewing machine,<br />

nor was he being a traditionalist. The<br />

reason was easily explained and quite<br />

obvious. He simply had no electricity.<br />

His shop was quite primitive, and opened<br />

to the sunlight, his only light source.<br />

I soon found this to be the norm of the<br />

Iraqi culture. Some Americans think they<br />

may be poor, but the comforts of a heated<br />

(or air conditioned) home, three meals a<br />

day, and a television are known by only<br />

the richest of Iraqis.<br />

Watching him work on my uniforms with<br />

an attention and pride in his creations,<br />

another Iraqi man, about half his age,<br />

entered his shop and interrupted the old<br />

man. He was obviously an interpreter for<br />

an American unit, as he was wearing an<br />

American army uniform. They exchanged<br />

a hug and some words in Arabic when<br />

the older of the men explained to me<br />

in broken English, “My son. One moment<br />

please, sorry, my friend.” His smile was<br />

a smile full of pride. It was pride that<br />

his son was an interpreter for the U.S.<br />

Army, but more so that it was simply his<br />

son. They continue to converse in Arabic<br />

and handling a piece of cloth, turning<br />

it, looking at it, and obviously making<br />

plans for it.<br />

“I’m sorry” the Iraqi in the uniform<br />

turns and apologizes to me. “I need<br />

to cover my face when I work with the<br />

Americans.” Not realizing it at the<br />

time, I later discovered that those<br />

interpreters not covering their faces<br />

on missions with the U.S. Army were not<br />

around long. Terrorists discovering the<br />

identity of an interpreter created two<br />

predictable situations: At best, the<br />

American employed Iraqi, along with his<br />

family, would be threatened and harassed<br />

until he or she resigns. More commonly,<br />

however, the aforementioned would be<br />

tortured and eventually murdered in an<br />

animalistic fashion.<br />

“No problem,” I replied calmly. I<br />

didn’t have anywhere to go. The young<br />

Iraqi turned to his father, presumably<br />

discussing further how he wanted this<br />

savior mask constructed. Watching father<br />

and son interact triggered a smile from<br />

ear to ear on my damp, dirty face. My<br />

eyes saw two grown men working on a<br />

project together, but my heart showed me<br />

a father and his ten your old son working<br />

together to create something magnificent,<br />

not unlike my father and I, once upon a<br />

time.<br />

I blinked. I saw my father and me<br />

working on a small block of wood.<br />

Drilling it, cutting it, painting it,<br />

Traveler