Paperskin: barkcloth across the Pacific - Queensland Art Gallery

Paperskin: barkcloth across the Pacific - Queensland Art Gallery

Paperskin: barkcloth across the Pacific - Queensland Art Gallery

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

2<br />

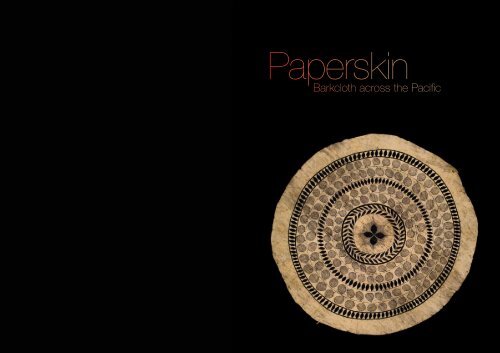

<strong>Paperskin</strong><br />

Barkcloth <strong>across</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pacific</strong>

Publishers<br />

<strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong><br />

stanley Place, south bank, brisbane<br />

PO box 3686, south brisbane<br />

<strong>Queensland</strong> 4101 Australia<br />

www.qag.qld.gov.au<br />

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa<br />

Cable street, Wellington<br />

PO box 467, Wellington<br />

New Zealand<br />

www.tepapa.govt.nz<br />

<strong>Queensland</strong> Museum<br />

Cnr Grey and Melbourne streets, south brisbane<br />

PO box 3300, south brisbane<br />

<strong>Queensland</strong> 4101 Australia<br />

www.qm.qld.gov.au<br />

Published for ‘<strong>Paperskin</strong>’, an exhibition organised by <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong>, Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa<br />

and <strong>Queensland</strong> Museum<br />

‘<strong>Paperskin</strong>: <strong>barkcloth</strong> <strong>across</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pacific</strong>’<br />

<strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong><br />

31 October 2009 – 14 February 2010<br />

‘<strong>Paperskin</strong>: The <strong>Art</strong> of Tapa Cloth’<br />

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa<br />

18 June 2010 – 26 september 2010<br />

CurATOrs<br />

PREVIOUS PAGE<br />

Siapo unknown<br />

Samoa<br />

Barkcloth, dye / 160cm (diam) /<br />

Collected 1885. Gift of Mr. D.<br />

Grahame, 1957 / Collection:<br />

Museum of New Zealand<br />

Te Papa Tongarewa<br />

Maud Page, Curator, Contemporary <strong>Pacific</strong> <strong>Art</strong>, <strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong><br />

sean Mallon, senior Curator, <strong>Pacific</strong> Cultures,<br />

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa<br />

imelda Miller, Assistant Curator, Torres strait islander and <strong>Pacific</strong> indigenous<br />

studies, <strong>Queensland</strong> Museum<br />

© <strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong>, Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa<br />

and <strong>Queensland</strong> Museum, 2009<br />

This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under <strong>the</strong> Copyright<br />

Act 1968, no part may be reproduced or communicated to <strong>the</strong> public without<br />

prior written permission of <strong>the</strong> publishers. No illustration may be reproduced<br />

without <strong>the</strong> permission of <strong>the</strong> copyright owners. Copyright for texts in this<br />

publication is held by <strong>the</strong> <strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong>, Museum of New Zealand<br />

Te Papa Tongarewa and <strong>Queensland</strong> Museum. Copyright of photographic<br />

images is held by individual photographers and <strong>the</strong> three institutions.<br />

isbN: 978 1 921503 09 2<br />

<strong>Paperskin</strong><br />

Barkcloth <strong>across</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pacific</strong><br />

<strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa <strong>Queensland</strong> Museum

Contents<br />

Foreword 6<br />

Tony ellwood / Michelle hippolite / ian Galloway<br />

Preface 8<br />

Nicholas Thomas<br />

<strong>Paperskin</strong>: An introduction 10<br />

Maud Page<br />

beyond <strong>the</strong> paperskin 22<br />

sean Mallon<br />

The <strong>Pacific</strong> perspective on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Queensland</strong><br />

Museum: Tradition is present in <strong>the</strong> past<br />

and here in <strong>the</strong> present 32<br />

imelda Miller<br />

Plates 38<br />

list of works 72<br />

selected bibliography 76<br />

Acknowledgments 78<br />

Authors 80

Foreword<br />

Tony Ellwood<br />

Michelle Hippolite<br />

Ian Galloway<br />

‘<strong>Paperskin</strong>’ brings toge<strong>the</strong>r works from hawai‘i to Papua New Guinea, dating from<br />

<strong>the</strong> late eighteenth century to 2006. since its introduction into <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pacific</strong> from islands<br />

of south-east Asia over 3000 years ago, cloth beaten from bark and patterned with<br />

striking designs has been an important mode of artistic and cultural expression in<br />

many <strong>Pacific</strong> nations and regions. Yet, in art history terms, it has not received <strong>the</strong><br />

attention accorded to o<strong>the</strong>r media. ‘<strong>Paperskin</strong>’ introduces Australian and New Zealand<br />

contemporary art audiences to <strong>the</strong>se works and to <strong>the</strong> cultures that made <strong>the</strong>m.<br />

The <strong>barkcloth</strong>s on display in this exhibition vary from intricate crosshatched designs from<br />

<strong>the</strong> solomon islands to spectacular performance masks from <strong>the</strong> baining and elema<br />

peoples of Papua New Guinea. The relationship to place is a significant element in all <strong>the</strong><br />

works; <strong>the</strong> importance of nature and <strong>the</strong> complex cosmologies of <strong>Pacific</strong> cultures are<br />

also evident. With strident use of patterning and colour, <strong>the</strong> cloths express <strong>the</strong> vitality of<br />

<strong>the</strong>se cultures and <strong>the</strong> importance of visual expression as a means of communication.<br />

The capacity for change, demonstrated by <strong>the</strong> incorporation of new ideas and<br />

materials, can be traced in <strong>the</strong> works created during <strong>the</strong> early period of colonisation and<br />

missionary activity in <strong>the</strong> late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.<br />

Given <strong>the</strong> importance of exchange for <strong>Pacific</strong> culture, all three institutions involved in<br />

<strong>the</strong> organisation of ‘<strong>Paperskin</strong>’ — <strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong>, Museum of New Zealand Te<br />

Papa Tongarewa and <strong>Queensland</strong> Museum — are delighted to have collaborated on<br />

<strong>the</strong> presentation of this significant exhibition. Works have been selected from each of<br />

our public collections and that of private collector harold Gallasch in south Australia.<br />

We are grateful to <strong>the</strong> curators, Maud Page, Curator of Contemporary <strong>Pacific</strong> <strong>Art</strong>,<br />

<strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong>; sean Mallon, senior Curator, <strong>Pacific</strong> Cultures, Museum of<br />

New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa; and imelda Miller, Assistant Curator, Torres strait<br />

islander and <strong>Pacific</strong> indigenous studies, <strong>Queensland</strong> Museum, for <strong>the</strong>ir commitment<br />

to <strong>the</strong> exhibition. We also extend our thanks to all <strong>the</strong> staff involved in realising this<br />

ambitious cross-Tasman project.<br />

PREVIOUS PAGE<br />

Mask (detail) unknown<br />

Papua New Guinea<br />

Orokolo, Gulf Province<br />

Barkcloth, dye, cane / 31.5 x<br />

95 x 21cm / Collected by S.G.<br />

MacDonell, 1913 / Collection:<br />

<strong>Queensland</strong> Museum<br />

Kapa (detail) 1770s<br />

Hawai‘i<br />

Barkcloth, dye / 63.5 x 129cm /<br />

A.H. Turnbull Collection.<br />

Presented by <strong>the</strong> Trustees of <strong>the</strong><br />

Turnbull Estate, 1918 / Collection:<br />

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa<br />

Tongarewa<br />

On a more sombre note, it is with great regret that we note <strong>the</strong> passing of Dr seddon<br />

bennington, who was Chief executive Officer of Museum of New Zealand Te Papa<br />

Tongarewa until his tragic death in July this year. seddon was an enthusiastic<br />

supporter of <strong>the</strong> ‘<strong>Paperskin</strong>’ exhibition throughout its development. his unerring<br />

commitment to <strong>the</strong> public relevance of state museums has been a significant<br />

inspiration to those working in <strong>the</strong> fields of art, culture and science in this region and<br />

he will be greatly missed.<br />

‘<strong>Paperskin</strong>’ is an important new consideration of <strong>the</strong> <strong>barkcloth</strong> medium. We trust<br />

that Australian and New Zealand audiences will find a rich source of inspiration in<br />

this exhibition.<br />

Tony Ellwood<br />

Director, <strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> / <strong>Gallery</strong> of Modern <strong>Art</strong><br />

Michelle Hippolite<br />

Acting Chief executive / Kaihautu, Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa<br />

Dr Ian Galloway<br />

Director and Chief executive Officer, <strong>Queensland</strong> Museum<br />

6 7

Preface<br />

Nicholas Thomas<br />

since <strong>the</strong> eighteenth century, <strong>the</strong> <strong>barkcloth</strong> of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pacific</strong> has intrigued travellers and<br />

captured <strong>the</strong> attention of connoisseurs in europe. From <strong>the</strong> 1770s, <strong>the</strong> decoration of<br />

Tongan ngatu, hawaiian kapa and o<strong>the</strong>r fabrics sparked <strong>the</strong> interest of collectors, and<br />

soon after Cook’s voyages, sheets of <strong>barkcloth</strong> began to be cut up for distribution<br />

among albums of samples. it was briefly <strong>the</strong> fashion for london ladies to adapt <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

garments, incorporating tapa, which has thus been a cross-cultural fabric for nearly<br />

250 years.<br />

if, early on, <strong>barkcloth</strong> spoke eloquently of <strong>the</strong> exotic, it is strange that it has only recently<br />

been seriously studied, and only recently recognised as a major Oceanic art form. Though<br />

<strong>the</strong>re are brief reports and discussions scattered through many early anthropological<br />

monographs, it was only in 1972 that a book dedicated to tapa in Polynesia (by simon<br />

Kooijman, a Dutch anthropologist) was published, and still more recently that a book (Neich<br />

and Pendergrast’s 1997 <strong>Pacific</strong> Tapa) with colour plates appeared, that could be said to do<br />

justice to <strong>the</strong> aes<strong>the</strong>tics of <strong>the</strong> medium. There are, of course, explanations for this neglect.<br />

Tribal art studies and art markets have long been biased toward sculptural forms<br />

and toward works of art made by men, while fabrics have been neglected. equally<br />

unfortunate was <strong>the</strong> perception that patterned and painted cloth is merely ‘decorated’,<br />

and decoration, perceived as a lower-order, sub-artistic level of cultural creativity. until<br />

recently, <strong>the</strong>se fabrics were seen as bearers of patterns ra<strong>the</strong>r than works of art, and<br />

were typically exhibited as backdrops in museum display cases ra<strong>the</strong>r than presented<br />

as objects that could be appreciated for <strong>the</strong>ir integral value.<br />

No major art exhibition has been dedicated to <strong>barkcloth</strong> until now. ‘<strong>Paperskin</strong>’ is a<br />

landmark project that brings into view a stunning selection of fabrics, primarily from <strong>the</strong><br />

rich but largely un-researched collections of Te Papa and <strong>the</strong> <strong>Queensland</strong> Museum.<br />

some of <strong>the</strong>se — <strong>the</strong> samoan, hawaiian and Fijian examples — will be familiar to those<br />

who already have an interest in <strong>the</strong> genre. but some, such as <strong>the</strong> animated Niuean<br />

Hiapo (detail) 19th century<br />

Niue (attributed)<br />

Barkcloth, dye / 105 x 171.5cm /<br />

Collection: Museum of New<br />

Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa<br />

hiapo example, are extraordinary and unlike any o<strong>the</strong>r Niuean piece in any collection,<br />

anywhere in <strong>the</strong> world. Hiapo such as <strong>the</strong>se remind us that <strong>the</strong>y are not examples of<br />

an object type but unique works of art. At <strong>the</strong> same time, <strong>barkcloth</strong>s are not solely, or<br />

not exactly, works of art: <strong>the</strong> terminological debate is ultimately unproductive, but it is<br />

important to remember that <strong>the</strong>se were not made for aes<strong>the</strong>tic appreciation in a narrow<br />

sense, but ra<strong>the</strong>r to constitute sanctity, to define a ceremony, to wrap around a body,<br />

to bear knowledge or to effect a gift. These art forms were embedded in <strong>the</strong> lives of<br />

<strong>Pacific</strong> islanders and in many places, and in many ways, <strong>the</strong>y still are.<br />

The curators are to be congratulated on a sparkling and singular exhibition which may<br />

be <strong>the</strong> first but should definitely not be <strong>the</strong> last. let us hope that it encourages islanders,<br />

artists, students, curators and o<strong>the</strong>r interested people to look again, and more intently, at<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>barkcloth</strong> of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pacific</strong>.<br />

Nicholas Thomas is Director of <strong>the</strong> Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology and Professor of historical<br />

Anthropology, Cambridge university.<br />

8 9

10<br />

Ngatu 1940s<br />

Tonga<br />

Barkcloth, dye / 196.4 x 160cm /<br />

Gift of Valerie Morris, 1989 /<br />

Collection: Museum of New<br />

Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa<br />

<strong>Paperskin</strong>: An introduction<br />

Maud Page<br />

in admiration of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pacific</strong> <strong>barkcloth</strong> samples brought home by early explorers,<br />

elizabeth Cook embroidered and fashioned a waistcoat from this cloth for her<br />

husband’s expected return in 1780. 1 Captain Cook, however, never felt its supple and<br />

silky texture on his skin: only his bones knew <strong>the</strong> material, when <strong>the</strong>se were carefully<br />

bundled in hawaiian <strong>barkcloth</strong> after his violent death at Kealakekua bay in 1779.<br />

<strong>barkcloth</strong> — wrapped around chiefly bodies, dancers, brides, grooms, babies and <strong>the</strong><br />

deceased, or offered as ceremonial gifts — is <strong>the</strong> subject of <strong>the</strong> ‘<strong>Paperskin</strong>’ exhibition,<br />

and conjures precious narratives from <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pacific</strong>.<br />

Across one third of <strong>the</strong> world, and over many centuries, <strong>Pacific</strong> people have been<br />

creating, adapting and repeating designs on <strong>the</strong> fibrous <strong>barkcloth</strong> surface. These<br />

creations can be utilitarian, but most are still used in important ceremonies. some<br />

<strong>barkcloth</strong>s record <strong>the</strong> passage of time, such as <strong>the</strong> Tongan ngatu featured in<br />

‘<strong>Paperskin</strong>’, which depicts Tonga’s World War Two alliances. 2 similarly, Niuean hiapo<br />

was sometimes used as parchment to inscribe <strong>the</strong> names of people and tracts of land,<br />

which often indicate <strong>the</strong> date <strong>the</strong> hiapo were created. 3 in o<strong>the</strong>r cultures, such as that<br />

of Papua New Guinea’s baining people, <strong>barkcloth</strong> is used to construct impermanent,<br />

intricate sculptures dedicated to transcendence of <strong>the</strong> temporal world.<br />

Whatever <strong>the</strong> intent, most <strong>barkcloth</strong>s exhibit an extraordinary array of dexterously<br />

applied geometric forms that transfix <strong>the</strong> eye. From <strong>the</strong> fine crosshatch work of <strong>the</strong><br />

solomon islands and Futuna practitioners to <strong>the</strong> bold, angular lines in Fijian textiles, and<br />

to <strong>the</strong> combination of straight and curved mark-making on Papuan <strong>barkcloth</strong>s, <strong>the</strong>re is<br />

in each an aes<strong>the</strong>tic of symmetry and dynamism. ‘<strong>Paperskin</strong>’ celebrates this art form,<br />

accentuating <strong>the</strong> diversity of its two-dimensional and sculptural practice while also<br />

noting some of <strong>the</strong> striking synergies in both pattern and use.<br />

To those outside <strong>the</strong> communities in which <strong>the</strong>y are generated, <strong>barkcloth</strong>’s visual<br />

idiom is largely incomprehensible. 4 in Papua New Guinea, for example, much of <strong>the</strong><br />

11

information in <strong>barkcloth</strong> designs is not meant to be shared with outsiders. The Omie<br />

women from Oro (or Nor<strong>the</strong>rn) Province, on <strong>the</strong> country’s north-east coast, speak of<br />

<strong>the</strong> cloths as <strong>the</strong>ir ‘wisdom’ and, of <strong>the</strong> symbols in <strong>the</strong>ir works, will recount only those<br />

intended for outsiders. The titles of <strong>the</strong>ir nioje (<strong>barkcloth</strong>s) refer to <strong>the</strong> rich, volcanic<br />

landscape that dominates <strong>the</strong>ir villages, including Mount lamington, mountains with<br />

clouds, jungle vines, tree bark, spider webs, frogs, and <strong>the</strong> backbones of mountain fish.<br />

Yet, each woman imagines this same landscape differently. some like Vivian Marumi<br />

can have entirely different interpretations of <strong>the</strong> same subject — one version of ‘jungle<br />

vines’ shows row upon row of symmetrically freehand horizontal lines as thick as a<br />

canopy. Ano<strong>the</strong>r images this same jungle as chaotic and filled with spirals, diamond<br />

shapes and blocks of colour. This interpretive freedom is bountiful and produces an<br />

incredible diversity in <strong>barkcloth</strong>s made within <strong>the</strong> same small, remote community.<br />

Australian writer Drusilla Modjeska spent time with <strong>the</strong>se artists, and recounts that:<br />

When a woman comes into her vai hero (wisdom), it is not simply that she has learned<br />

<strong>the</strong> iconography, but that she lives it so fully that it forms, and informs, her relationship<br />

with <strong>the</strong> cloth. 5<br />

Modjeska’s engagement with <strong>the</strong> nioje, and her attempt to divulge customary<br />

knowledge of <strong>the</strong> work and practice to a Western audience, is evocative of how o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

<strong>barkcloth</strong> from <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pacific</strong> can be viewed:<br />

While <strong>the</strong> alphabet of motifs can be named, it is absorbed in such a way that parts do<br />

not require naming. The iconography works not by being broken into separate elements,<br />

but by a complex patterning of sensation and image that is not translatable — a way of<br />

seeing that is affective as well as instructive. 6<br />

As with much o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>Pacific</strong> <strong>barkcloth</strong>, <strong>the</strong> Omie’s nioje is a physical manifestation of<br />

<strong>the</strong> makers — who <strong>the</strong>y are, <strong>the</strong>ir locality, <strong>the</strong>ir history and <strong>the</strong>ir cosmology. Titles<br />

of abstract works, such as ‘clan history’ and ‘wisdom’, allude to <strong>the</strong>se textiles’<br />

genealogical memory. The Omie say <strong>the</strong>ir wisdom is intertwined with <strong>the</strong> wellbeing of<br />

12<br />

ABOVE<br />

Vivian Marumi<br />

Papua New Guinea b.1980<br />

Omie people, Oro Province<br />

Odunege 1 (Jungle vines 1) 2006<br />

Barkcloth, dye / 142 x 114cm /<br />

Purchased 2007. <strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong><br />

<strong>Gallery</strong> Foundation<br />

RIGHT<br />

Vivian Marumi<br />

Odunege 4 (Jungle vines 4)<br />

(detail) 2006<br />

Barkcloth, dye / 163 x 99cm /<br />

Purchased 2007. <strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong><br />

<strong>Gallery</strong> Foundation

Mount lamington. its eruption in 1951, <strong>the</strong> resulting deaths of 4000 of <strong>the</strong>ir Orokaivian<br />

neighbours and <strong>the</strong>ir own dislocation is interpreted as a consequence of <strong>the</strong> war on <strong>the</strong><br />

Kokoda Trail which, among o<strong>the</strong>r horrors, grounded <strong>the</strong> dead soldiers’ restless spirits.<br />

some Omie blamed <strong>the</strong> eruption on <strong>the</strong> persistence of customary practices over those<br />

of Christianity, and proceeded to erase many of <strong>the</strong>m. As a consequence, initiation<br />

ceremonies and <strong>the</strong> ensuing tattooing of clan insignia on <strong>the</strong> body ceased and designs<br />

were instead transposed to <strong>barkcloth</strong>. <strong>Art</strong>ist Nerry Keme has said, ‘i paint on <strong>barkcloth</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> designs that were on my grandparents’ bodies’. 7 These materialise on <strong>the</strong> nioje as<br />

three small concentric circles, repeated in several configurations <strong>across</strong> <strong>the</strong> textile, and<br />

were once confined to <strong>the</strong> area around <strong>the</strong> navels of her ancestors. in reviewing this<br />

dynamic transposition, Modjeska refers to <strong>the</strong>se as ‘double skin’ designs.<br />

When speaking about <strong>barkcloth</strong>, <strong>the</strong> allusion to marked skin is particularly evocative<br />

and has been used in connection with o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>Pacific</strong> practices. Anthropologist Alfred<br />

Gell noted that <strong>the</strong> Marquesans called <strong>the</strong>ir full-body tattoos pahu tiki, which translates<br />

as ‘wrapping in images’. researching samoan tattooing practices, he later concluded<br />

that <strong>the</strong>y functioned as a second skin — wrapping, protecting and containing <strong>the</strong><br />

person’s essence. The similarity of motifs from samoan tattoos to <strong>the</strong>ir siapo (<strong>barkcloth</strong>)<br />

is evident in works from <strong>the</strong> collection of Wellington’s Museum of New Zealand Te Papa<br />

Tongarewa, such as a 1940s example composed of horizontal rows of triangles. 8 Many<br />

<strong>Pacific</strong> peoples, most notably Tongans and Fijians, also wrap <strong>the</strong>ir bodies in <strong>barkcloth</strong><br />

for important ceremonies. like tattooing, <strong>the</strong> cloth confers an entire matrix of meaning<br />

on <strong>the</strong> bearer. A drawing from 1877 shows a Fijian chief layered head to toe in masi with<br />

an accompanying description around that time, claiming that over 200 metres of cloth<br />

could be used for this purpose.<br />

There are many accounts of <strong>barkcloth</strong> being treated as an extension of <strong>the</strong> body — an<br />

extension of <strong>the</strong> skin. samoans would wrap <strong>barkcloth</strong> around <strong>the</strong> bride, and <strong>the</strong> material<br />

would <strong>the</strong>n be ritually stained by <strong>the</strong> first intercourse. 9 Fijians rubbed turmeric on <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

The Tui Nadrau, dressed in masi<br />

for ceremonial presentation.<br />

Drawn from life by Theodor<br />

Kleinschmidt, Natuatuacoko,<br />

October, 1877 / Fiji Museum<br />

Collection<br />

Masi (detail) unknown<br />

Fiji<br />

Barkcloth, dye / 94.5 x 127.5cm /<br />

Collection: Museum of New<br />

Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa<br />

masi as well as on <strong>the</strong> bodies of a new mo<strong>the</strong>r and baby, binding <strong>the</strong>m indistinguishably<br />

in this sweet-smelling, warm, earthy spice. likewise, <strong>the</strong> dead were also impregnated<br />

with turmeric and laid upon masi in <strong>the</strong>ir graves. 10 in 1920s Collingwood bay, Papua New<br />

Guinean women used to crawl around <strong>the</strong> village beneath a <strong>barkcloth</strong> when mourning<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir husbands, <strong>the</strong> cloth isolating <strong>the</strong>m from sight and contact. 11<br />

Archaeologists Chris ballard and Meredith Wilson have posited a relationship between<br />

Melanesian rock art designs and those on tapa, specifically in mortuary contexts. The<br />

motifs, <strong>the</strong>y argue, transfer between <strong>the</strong> two media and also appear in tattoos, carvings<br />

and engravings. 12 As ballard has said:<br />

Most of <strong>the</strong> rock art sites with tapa motifs are burial sites, with human remains in cliff<br />

niches or caves, and <strong>the</strong>re are lots of instances of tapa being used to cover <strong>the</strong> bones,<br />

as a form of surrogate skin. 13<br />

O<strong>the</strong>r scholars have also pointed to <strong>the</strong> link between designs found on ancient<br />

<strong>Pacific</strong> lapita pottery, tattooing and <strong>barkcloth</strong>s, alluding to a complex aes<strong>the</strong>tic that is<br />

revitalised and used in a number of different art forms. 14 This ubiquitous transference<br />

of motifs can be understood as a method of communication (particularly as <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pacific</strong><br />

region had no written language prior to european contact), and its continued use<br />

suggests an audience for whom <strong>the</strong>se symbols represent a particular sense of being<br />

and place.<br />

For <strong>the</strong> baining people of <strong>the</strong> mountainous Gazelle Peninsula of New britain, Papua<br />

New Guinea, <strong>the</strong> creation of <strong>barkcloth</strong> masks enacts an intricate relationship with both<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir everyday agricultural subsistence and that of <strong>the</strong> spirits, particularly those of <strong>the</strong><br />

recently departed. The ten baining masks in ‘<strong>Paperskin</strong>’ represent only a portion of <strong>the</strong><br />

sculptures being made today, and include works from throughout <strong>the</strong> peninsula. 15 The<br />

masks are worn by men, with rare exceptions, such as <strong>the</strong> two Siviritki with fringes and<br />

accompanying fibre skirts that camouflage <strong>the</strong> dancer. each of <strong>the</strong> ten masks — except<br />

14 15

for <strong>the</strong> four-metre-high, three-pronged work — exhibit <strong>the</strong> baining characteristics of<br />

large, accentuated eyes, accompanied by vibrant designs painted directly onto <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>barkcloth</strong> in a restricted palette of red and black.<br />

These complex sculptures are used for a single ceremony and <strong>the</strong>n discarded,<br />

even though <strong>the</strong>y consume much of <strong>the</strong> villagers’ time and resources. The abstract<br />

designs featured on both sides are drawn mostly from memory, allowing for individual<br />

interpretation and change. Although customarily using designs drawn from nature —<br />

such as wild vines, insects or even pig intestines (<strong>the</strong> latter being a pattern used in<br />

several masks in ‘<strong>Paperskin</strong>’) — more recent designs include those derived from car<br />

tyre treads, mission crosses and manufactured cloth, as well as introduced figurative<br />

elements, such as flags and <strong>the</strong> ‘thumbs up’ gesture.<br />

The masks are produced for day or night ceremonies and represent female and male<br />

spirits in <strong>the</strong> form of animals or composite beings, such as bird–humans or snake–<br />

birds. Day dances are commonly associated with <strong>the</strong> commemoration of <strong>the</strong> dead and<br />

with <strong>the</strong> cyclical fertility of harvests and gardens, while night fire dances are thought to<br />

pertain to male initiation.<br />

A 1931 written account of a night fire ceremony is remarkably similar to more recent<br />

accounts, from <strong>the</strong> 1970s to <strong>the</strong> mid 2000s, as described by collector harold Gallasch.<br />

This points to <strong>the</strong> continued relevance of <strong>the</strong> practice despite <strong>the</strong> advent of modernity. 16<br />

each begins by noting <strong>the</strong> anticipation of <strong>the</strong> villagers following a long period of mask<br />

preparation, which occurs in locations inaccessible to women and children. Pigs are killed,<br />

food is distributed and a large bonfire ignited in <strong>the</strong> centre of <strong>the</strong> village. Gallasch recounts:<br />

. . . [A]t its zenith <strong>the</strong> chanting and drumming increased in tempo, as if in great<br />

urgency. Sweeping in from <strong>the</strong> blackness of <strong>the</strong> night, of <strong>the</strong> jungle, came <strong>the</strong><br />

apparition of a bush spirit, a large white face outlined in red and black, large eyes to<br />

see in <strong>the</strong> darkness. As it came closer <strong>the</strong> disembodied face, shrouded behind <strong>the</strong><br />

16<br />

ABOVE<br />

Kavat masks in performance,<br />

Malasaet village, East New Britain<br />

Province, Papua New Guinea,<br />

2009 / Image courtesy: John Wilson<br />

RIGHT<br />

Gabriel Asekia<br />

Papua New Guinea, b. Unknown<br />

Sibali Baining people, East New<br />

Britain Province<br />

Anui Lagun<br />

Papua New Guinea, b. Unknown<br />

Sibali Baining people, East New<br />

Britain Province<br />

Mandas mask c. 1995<br />

Barkcloth, dye, felt pen, cane /<br />

410 x174 x 40cm / Collection:<br />

Harold Gallasch, Hahndorf, South<br />

Australia<br />

17

18<br />

Kavat mask (front and back) 1971<br />

Papua New Guinea<br />

Kairak Baining people, East New<br />

Britain Province<br />

Barkcloth, paper, dye, felt<br />

pen, wood and cane / 135 x<br />

133 x 60cm / Purchased<br />

2009. <strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong><br />

Foundation Grant.<br />

croton leaves, was propelled on black legs, pounding in time with <strong>the</strong> drumming,<br />

racing forwards, reversing, <strong>the</strong>n stomping ever closer, <strong>the</strong> head swaying and<br />

pirouetting . . . children screamed in fear and ran to escape. In one last, swift burst<br />

of fervour, <strong>the</strong> masked apparition turned, raced and jumped in to <strong>the</strong> centre of <strong>the</strong><br />

bonfire. There, for a few long seconds it stomped and twisted, burning sticks and<br />

embers scattering in all directions. 17<br />

The baining masks in ‘<strong>Paperskin</strong>’ bear <strong>the</strong> traces of <strong>the</strong>ir performance: soot from fires,<br />

and <strong>the</strong> remnants of dyes and oils used to paint and perfume <strong>the</strong> dancer’s skin.<br />

however, <strong>the</strong>se masks are more than <strong>the</strong>atrical devices: <strong>the</strong>y allow for an interaction<br />

with, and a continuation of, a specific cosmology. living in <strong>the</strong> Gazelle Peninsula in <strong>the</strong><br />

1970s, <strong>the</strong>ologians Karl hesse and Theo Aerts recorded that <strong>the</strong> ‘baining worldview<br />

accepts as it were two worlds, in which <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r one (a rimbab) is <strong>the</strong> replica of this<br />

world’. 18 The invisibility of <strong>the</strong> rimbab becomes visible in <strong>the</strong> dances. Masked, <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

bodies adorned with paint and leaves, <strong>the</strong> dancers become <strong>the</strong> manifestation of spirits:<br />

They show <strong>the</strong> forces of nature — but at <strong>the</strong> same time also <strong>the</strong>ir limitations — <strong>the</strong><br />

power of man, and <strong>the</strong> ambiguity of his relationship with that which is constantly<br />

beyond his immediate grasp. 19<br />

in many cultures <strong>across</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pacific</strong>, <strong>barkcloth</strong> continues to be significant. The<br />

deliberate repetition of geometric patterns has enabled a visual idiom historically linking<br />

<strong>barkcloth</strong> with o<strong>the</strong>r important cultural practices such as tattooing and weaving, as<br />

well as defunct art forms such as rock engravings and lapita pottery. recognition<br />

and appreciation of <strong>the</strong>se designs has ensured <strong>the</strong> art form’s ongoing practice. On<br />

a fibrous surface, using a restricted colour palette and limited combinations of linear<br />

and curvilinear non-figurative designs, <strong>barkcloth</strong> makers have created extraordinarily<br />

diverse works that mediate <strong>the</strong> social and spiritual transformation of both individuals<br />

and groups.<br />

For some, <strong>the</strong> need to sustain this practice — to work communally, and to have goods<br />

to give and exchange — is so strong that, even when lacking <strong>the</strong> essential materials,<br />

<strong>the</strong>y continue to innovate. in <strong>the</strong> mid 1990s in sydney’s west, for example, susana<br />

Kaafi ga<strong>the</strong>red a group of women toge<strong>the</strong>r to cut and glue interfacing material into long<br />

strips. laying <strong>the</strong>m onto a large makeshift table in Kaafi’s backyard, <strong>the</strong>y <strong>the</strong>n painted<br />

<strong>the</strong> strips — using <strong>the</strong> dust scraped from red bricks — with <strong>the</strong> gridded emblems of <strong>the</strong><br />

Tongan monarchy alongside stylised images of <strong>the</strong> sydney Opera house.<br />

Maud Page is Curator, Contemporary <strong>Pacific</strong> <strong>Art</strong>, <strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> / <strong>Gallery</strong> of Modern <strong>Art</strong>.<br />

19

ACKNOWleDGMeNT<br />

i would like to acknowledge <strong>the</strong><br />

research and thoughtful input<br />

of ruth McDougall, Curatorial<br />

Assistant, Asian and <strong>Pacific</strong> <strong>Art</strong>,<br />

<strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> / <strong>Gallery</strong> of<br />

Modern <strong>Art</strong> to ‘<strong>Paperskin</strong>’.<br />

eNDNOTes<br />

1 Peter sharrad, ‘Trade and<br />

textiles in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pacific</strong> and india’,<br />

in Diana Wood Conroy and<br />

emma ru<strong>the</strong>rford, Fabrics<br />

of Change: Trading Identities<br />

[exhibition catalogue], university<br />

of Wollongong, NsW, p.14.<br />

2 see Adrienne Kaeppler,<br />

‘The structure of Tongan<br />

<strong>barkcloth</strong> design’, in <strong>Pacific</strong><br />

<strong>Art</strong>: Persistence, Change and<br />

Meaning, Anita herle, Nick<br />

stanley, Karen stevenson and<br />

robert l Welsch (eds), Crawford<br />

house Publishing, hindmarsh,<br />

sA, 2002, pp.291–309.<br />

3 John Pule in John Pule and<br />

Nicholas Thomas, Hiapo:<br />

Past and Present in Niuean<br />

Barkcloth, university of Otago<br />

Press, Dunedin, 2005, p.47.<br />

4 simon Kooijman in his seminal<br />

and often quoted 1972 text on<br />

<strong>barkcloth</strong>, Tapa in Polynesia,<br />

thought that fur<strong>the</strong>r study was<br />

needed on <strong>the</strong> names given to<br />

<strong>barkcloth</strong> patterns to decipher<br />

some of <strong>the</strong> meanings, but<br />

concluded that, ‘in <strong>the</strong> present<br />

state of our knowledge<br />

<strong>the</strong>y have no interpretative<br />

significance’ and <strong>the</strong>refore did<br />

not include any. There has been<br />

some attempt at adding to this<br />

body of knowledge, but by and<br />

large, <strong>the</strong>re remains remarkably<br />

little written information on<br />

<strong>barkcloth</strong> motifs <strong>across</strong><br />

Polynesia and Melanesia.<br />

One pertinent example is rod<br />

ewins’s 1982 research on<br />

Fijian motifs (originally related<br />

to mats) and his more recent<br />

study of <strong>the</strong>se in Staying Fijian:<br />

Vatulele Island Barkcloth and<br />

Social Identity, Crawford house<br />

Publishing, hindmarsh, sA,<br />

and university of hawaii Press,<br />

honolulu, 2009.<br />

5 Drusilla Modjeska, ‘This<br />

place, our art’, in Omie: The<br />

Barkcloth <strong>Art</strong> of Omie, [exhibition<br />

catalogue], Annandale Galleries,<br />

sydney, 2006, p.16.<br />

6 Modjeska, in Omie: The<br />

Barkcloth <strong>Art</strong> of Omie, p.16.<br />

rod ewins, speaking on Fijian<br />

masi (<strong>barkcloth</strong>), also states:<br />

‘Thus it is <strong>the</strong> totality of <strong>the</strong><br />

pattern that gives meaning,<br />

and no one component of <strong>the</strong><br />

pattern can carry more than a<br />

small part of <strong>the</strong> meaning by<br />

itself’, in Staying Fijian: Vatulele<br />

Island Barkcloth and Social<br />

Identity, p.147.<br />

7 Omie: The Barkcloth <strong>Art</strong> of<br />

Omie, p.29.<br />

8 Caption details: Siapo mamanu,<br />

samoa, <strong>barkcloth</strong>, dye / 173.5 x<br />

128.2cm / Collected by sir Guy<br />

richardson Powles c.1949–60.<br />

Gift of Michael Powles, 2001 /<br />

Collection: Museum of New<br />

Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa<br />

9 Nicholas Thomas, ‘The case<br />

of <strong>the</strong> misplaced ponchos:<br />

speculations concerning <strong>the</strong><br />

history of cloth in Polynesia’,<br />

in Clothing <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pacific</strong>, Chloe<br />

Colchester (ed.), berg, Oxford,<br />

2003, p.90.<br />

10 simon Kooijman, Tapa in <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Pacific</strong>, bernice P. bishop<br />

Museum bulletin 234, bishop<br />

Museum Press, honolulu,<br />

hawai‘i, 1972, p358.<br />

11 roger Neich and Mick<br />

Pendergrast, <strong>Pacific</strong> Tapa, David<br />

bateman, Auckland Museum,<br />

Auckland, 1997, p.136.<br />

12 Chris ballard, email to <strong>the</strong><br />

author, 4 March 2009.<br />

13 rod ewins has also observed<br />

that human remains were<br />

found wrapped in black masi in<br />

a mortuary cave in Vanualevu,<br />

Fiji, in Staying Fijian: Vatulele<br />

Island Barkcloth and Social<br />

Identity, p.138.<br />

14 Most of Papua New Guinea,<br />

<strong>the</strong> outer islands and parts of<br />

<strong>the</strong> solomon islands have been<br />

inhabited for over 40 000 years.<br />

The rest of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pacific</strong> was settled<br />

by speakers of Austronesian<br />

languages from south-east<br />

Asia approximately 4000 years<br />

ago. This expansion is marked,<br />

in particular, by <strong>the</strong> distinctive<br />

Barkcloth (detail) 19th century<br />

Papua New Guinea<br />

Doriri people, Oro Province<br />

Barkcloth, dye / 57.6 x 117.3cm /<br />

Collected by Captain F.R. Barton,<br />

1901. Donated 1966 / Collection:<br />

<strong>Queensland</strong> Museum<br />

pottery style known as lapita.<br />

15 it includes work by <strong>the</strong> simbali<br />

people in <strong>the</strong> south of <strong>the</strong><br />

Gazelle Peninsula, <strong>the</strong> Chachet<br />

in <strong>the</strong> north-west, and <strong>the</strong><br />

uramot and Kairak people in<br />

<strong>the</strong> central and central-east<br />

regions of <strong>the</strong> tip of this New<br />

britain island.<br />

16 see W.J. read, ‘A snake dance<br />

of <strong>the</strong> baining’, in Oceania,<br />

vol. 3, 1931–32, pp.232–37.<br />

17 harold Gallasch, letter to <strong>the</strong><br />

author, 20 July 2009.<br />

18 Karl hesse and Theo Aerts,<br />

Baining Life and Lore, university<br />

of Papua New Guinea Press,<br />

Port Moresby, 1996, p.41.<br />

19 hesse and Aerts, Baining Life<br />

and Lore, p.41.<br />

20 21

Hiapo (detail) 19th century<br />

Niue (attributed)<br />

Barkcloth, dye / 97 x 216cm / Gift<br />

of A. Hamilton, 1912 / Collection:<br />

Museum of New Zealand Te<br />

Papa Tongarewa<br />

Beyond <strong>the</strong> paperskin<br />

Sean Mallon<br />

My grandfa<strong>the</strong>r was buried in Whenuatapu Cemetery, on a gentle hillside near Porirua<br />

City, in New Zealand. his casket was wrapped in a large Tongan ngatu. he was<br />

samoan and a matai (chief) in our extended family, and he was laid to rest in cold clay<br />

soil, an ocean away from home.<br />

One of my museum colleagues, a Tongan, was preparing human skulls for special<br />

storage in Te Papa’s wahi tapu. 1 she chose to individually wrap each skull in small<br />

sheets of plain <strong>barkcloth</strong> from Tonga. like my grandfa<strong>the</strong>r, <strong>the</strong>se human remains,<br />

collected in <strong>the</strong> nineteenth and twentieth centuries from Papua New Guinea, were far<br />

from <strong>the</strong>ir place of origin.<br />

Ano<strong>the</strong>r former colleague was married in Newtown, Wellington, in a flowing wedding<br />

dress made from undecorated <strong>barkcloth</strong> from Fiji and Tonga. she walked down <strong>the</strong><br />

aisle of <strong>the</strong> Congregational Christian Church of samoa on a length of ngatu more than<br />

12 metres long.<br />

in <strong>the</strong> 2005 Auckland secondary schools’ Polyfest dance competition, a samoan<br />

fuataimi for Auckland Girls’ Grammar school wore a dress made from ngatu. she led<br />

her dance troupe to first place in front of a captive audience on <strong>the</strong> ‘samoan stage’. 2<br />

The use of <strong>barkcloth</strong> in <strong>the</strong>se different situations fascinates me. how is it that Tongan<br />

tapa can officiate as a wrapping, a garment and a draping in cultural situations that are<br />

not Tongan? What enables <strong>barkcloth</strong> to move between cultural contexts and functions?<br />

Why wrap Papua New Guinean trophy skulls in Tongan <strong>barkcloth</strong>? What guides <strong>the</strong><br />

choices that allow this to happen? Are <strong>the</strong>re o<strong>the</strong>r aes<strong>the</strong>tic dimensions in <strong>the</strong> layers of<br />

this special cloth? These questions permit us to probe for <strong>the</strong> significance of <strong>barkcloth</strong><br />

among <strong>the</strong> contemporary diasporas of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pacific</strong>. They allow us to consider <strong>barkcloth</strong>s<br />

as mediators of actions that are not reliant on its markings, and to ask whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> art of<br />

<strong>barkcloth</strong> is contained in <strong>the</strong> markings of its ‘paper skin’, or beneath and beyond <strong>the</strong>m.<br />

23

Traffic in ideas and cultural material is not new to Polynesia and its peoples. since at<br />

least <strong>the</strong> 1700s, Tonga, samoa and Fiji have influenced each o<strong>the</strong>r culturally and have<br />

been connected through networks of exchange. Textiles, whales’ teeth, tattooing and<br />

people were among <strong>the</strong> commodities that moved between islands. in <strong>the</strong> twenty-first<br />

century, <strong>the</strong> sharing and appropriation of cultural material continues within <strong>the</strong> island<br />

archipelagos and beyond. in New Zealand, this sharing is sometimes conspicuous, in<br />

a cultural milieu where <strong>the</strong> assertion of ethnic distinctions is important, as much as <strong>the</strong><br />

formation of cultural alliances is strategic.<br />

in ‘<strong>Paperskin</strong>’, <strong>the</strong> decorated <strong>barkcloth</strong>s, displayed in warm, artificial light, offer a<br />

view that highlights design, composition, symmetry, and <strong>the</strong> creative impulses of<br />

individuals and groups. This type of presentation encourages us to see <strong>barkcloth</strong> with<br />

a heightened sense of its surface qualities, and enhances <strong>the</strong> possibilities for viewing<br />

<strong>the</strong>se textiles as creative works. it also offers us a chance to examine <strong>the</strong> patterns,<br />

linger over motifs and look for cultural and individual distinctions; to see <strong>the</strong> differences<br />

and similarities <strong>across</strong> this medium. The art of <strong>barkcloth</strong> is also evident in <strong>the</strong> labourintensive<br />

working of <strong>the</strong> raw materials, <strong>the</strong> preparation and beating of <strong>the</strong> cloth and<br />

fibres, and <strong>the</strong> manufacture of pigments and dyes.<br />

‘<strong>Paperskin</strong>’ is a departure from presentations of <strong>barkcloth</strong> as <strong>the</strong> backdrop to o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

artefacts, common in <strong>the</strong> museum exhibitions of <strong>the</strong> past. There is something more<br />

at work here, something not overtly named in <strong>the</strong> exhibition, but intrinsic to it — in <strong>the</strong><br />

curation and selection of <strong>the</strong> <strong>barkcloth</strong>s, and in <strong>the</strong> creation of <strong>the</strong> works <strong>the</strong>mselves.<br />

We often think of <strong>barkcloth</strong> in its decorated, finished form. however, while <strong>barkcloth</strong> is<br />

often beautifully decorated, given as a gift, or wrapped around objects or people, it is<br />

also a raw material giving shape and texture to things. <strong>barkcloth</strong> helps manifest social<br />

processes and cultural values. it mediates in ceremonies and events, and its uses and<br />

value often transcend its appearance, its surface decorations and artistic intent. The art<br />

of <strong>barkcloth</strong>, <strong>the</strong> art of tapa, is nei<strong>the</strong>r paper thin nor skin deep.<br />

in New Zealand-based <strong>Pacific</strong> island communities, familiarity with <strong>barkcloth</strong> does not<br />

always indicate an awareness of <strong>the</strong> specificities of its origin. <strong>barkcloth</strong> is often used like<br />

an old-time museum display: it serves as a backdrop at community meetings, at news<br />

conferences; it hangs in community buildings, politicians’ offices, in school hallways.<br />

it is also used in presentations, in funerals and weddings, or as a ceremonial garment.<br />

in <strong>the</strong>se situations, <strong>barkcloth</strong> is almost always Tongan or Fijian in origin, due to <strong>the</strong><br />

continuity of <strong>the</strong> art form and scale of production on those islands. samoan <strong>barkcloth</strong><br />

is not produced in similar sizes and quantities. Many <strong>Pacific</strong> islanders can visually<br />

distinguish a Fijian masi from a Tongan ngatu, although <strong>the</strong>y may not always know <strong>the</strong><br />

indigenous terms to describe <strong>the</strong>m. Despite <strong>the</strong>ir specific cultural origins, <strong>the</strong>y are often<br />

generically referred to as tapa. 3<br />

Why is this so? it seems that although masi and ngatu have distinctive markings, 4<br />

<strong>Pacific</strong> peoples in New Zealand find uses for <strong>the</strong>m that transcend <strong>the</strong>ir culture of origin.<br />

As textiles, <strong>the</strong>y can convey meaning beyond <strong>the</strong> motifs that signal <strong>the</strong>ir Tongan-ness,<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir Fijian-ness. it is as if <strong>the</strong>se elements, while distinctive and readable, are not always<br />

relevant. The textiles and <strong>the</strong> people who use <strong>the</strong>m are not bound to <strong>the</strong> nation.<br />

24<br />

Siapo mamanu (detail) 1940s<br />

Samoa<br />

Barkcloth, dye / 173.5 x 128.2cm /<br />

Collected by Sir Guy Richardson<br />

Powles c.1949–60. Gift of Michael<br />

Powles, 2001 / Collection:<br />

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa<br />

Tongarewa

26<br />

Pare’eva (mask) unknown<br />

Cook Islands, Mangaia,<br />

(attributed)<br />

Barkcloth, dye / 66cm x 30cm x<br />

20cm / Collected by T.W. Kirk. Gift<br />

of Masonic Lodge, Paraparaumu,<br />

1950 / Collection: Museum of New<br />

Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa<br />

This often happens when objects travel; when <strong>the</strong>y are used to mediate new social<br />

situations in new places. in art forms such as music, dance, tattooing and oratory,<br />

<strong>the</strong>re are innovations reflecting location-specific circumstances. The greater <strong>the</strong><br />

distance that tapa (or o<strong>the</strong>r cultural products) travel in institutional, spatial and temporal<br />

terms, knowledge related to <strong>the</strong>m becomes increasingly ‘partial, contradictory and<br />

differentiated’. 5 As ngatu or masi moves fur<strong>the</strong>r from its place of origin, <strong>the</strong> narratives,<br />

knowledge and contexts that give meaning to it in one place fragment and become<br />

less clear, eventually reflecting new ‘local’ concerns, transmitting some key cultural<br />

messages, and taking on new ones.<br />

Tapa may be admired for <strong>the</strong>ir beautiful decoration, but <strong>the</strong>y are also a medium<br />

for negotiating <strong>the</strong> politics of relationships and cultural identity. The fur<strong>the</strong>r a group<br />

is away from home, <strong>the</strong> more charged or urgent expressions of ethnic or cultural<br />

identity can become. Groups of people will often temporarily seek out, latch onto and<br />

express identity through cultural practices in order to make sense of <strong>the</strong> particular<br />

circumstances in which <strong>the</strong>y find <strong>the</strong>mselves. serving this purpose, tapa does its<br />

‘cultural’ work not only through <strong>the</strong> pigment that decorates its surface, but also<br />

through <strong>the</strong> fibres comprising <strong>the</strong> cloth itself.<br />

in <strong>the</strong> case of my grandfa<strong>the</strong>r’s burial casket, <strong>the</strong> ngatu in which it was wrapped was<br />

a way of reconnecting him to his island home, not through a cloth that was samoan,<br />

but through a cloth that was foreign to <strong>the</strong> cold clay soil, a cloth that was indigenous to<br />

a place beyond New Zealand’s shores. it also highlighted <strong>the</strong> fact that, while he lived<br />

<strong>the</strong> last decades of his life with us in New Zealand, he was of ano<strong>the</strong>r place. he was a<br />

samoan, a <strong>Pacific</strong> islander, and <strong>the</strong> tapa helped to bridge this distance, reconnecting<br />

him to his island identity despite <strong>the</strong> ngatu’s Tongan motifs. similarly, my colleague’s<br />

wrapping of <strong>the</strong> trophy skulls in <strong>barkcloth</strong> was perhaps a means of reconnecting<br />

<strong>the</strong>m with a tangible representation of something ‘<strong>Pacific</strong>’, a way of separating <strong>the</strong>m<br />

and protecting <strong>the</strong>m while <strong>the</strong>y were in <strong>the</strong> liminal space of a museum storeroom. My<br />

colleague’s <strong>barkcloth</strong> wedding garment was beautiful, and <strong>the</strong> church itself was draped<br />

in an extravagant length of ngatu down <strong>the</strong> aisle. The dress was remarkable: its texture;<br />

its plain, natural colour; <strong>the</strong> heavy drape of <strong>the</strong> cloth. undecorated with <strong>the</strong> freehand<br />

motifs of a samoan siapo mamanu or <strong>the</strong> rubbed-on patterns of a siapo ’elei, observers<br />

remarked on its similarity to raw silk, its tactility. 6 For <strong>the</strong> wearer, <strong>the</strong> garment was valued<br />

more than for its cosmetic appearance, and reflected ‘a love and passion for things <strong>Pacific</strong>’. 7<br />

in <strong>the</strong> examples i have described above, <strong>the</strong> functional value of <strong>barkcloth</strong>, as a<br />

decorated object, is less important than its symbolic value. On <strong>the</strong>se occasions,<br />

<strong>barkcloth</strong> mediates and creates relationships; it bridges distance and time. The use<br />

of <strong>barkcloth</strong> in <strong>the</strong>se situations shows that tapa mediates actions that are not solely<br />

reliant on <strong>the</strong> markings on its surface. The cloth itself can be important — <strong>the</strong> texture,<br />

<strong>the</strong> memory imbued in its layers, <strong>the</strong> worked fibres and <strong>the</strong> energy of <strong>the</strong> maker.<br />

While we know that <strong>the</strong> value attached to materials often affects <strong>the</strong> value attached to<br />

things, <strong>the</strong>y are not <strong>the</strong> same. 8 The materiality of <strong>barkcloth</strong>, its geo-cultural origins and<br />

‘o<strong>the</strong>rness’ are aes<strong>the</strong>tic dimensions that are easily overlooked, but <strong>the</strong>y are important<br />

in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pacific</strong> island diaspora, and particularly in a world where <strong>the</strong> production of<br />

cultural material is less fixed and its movement more global.<br />

27

in New Zealand, people share a range of meanings and value around tapa despite <strong>the</strong><br />

culturally distinct manner in which <strong>the</strong>y are marked. in <strong>the</strong> diaspora, tapa mediates a<br />

form of cultural recovery in a global maelstrom. i think that, for many <strong>Pacific</strong> islanders<br />

in New Zealand, regardless of <strong>the</strong>ir origins or descent, <strong>barkcloth</strong> is symbolic of an<br />

idealised past (or present) way of life that is geographically distant. Tapa is a tangible<br />

link to ‘a past’ as well as a signifier of cultural conditions in <strong>the</strong> present. indeed, Fijian<br />

Nina Nawalowalo has described masi as a ‘map back to my own cultural roots’ with<br />

‘<strong>the</strong> fibres’ providing a way back ‘to a time and place’. 9 What <strong>the</strong> case studies above<br />

have in common is <strong>the</strong> deployment of tapa as a tool for bringing <strong>the</strong> past closer to <strong>the</strong><br />

present. Tapa, like o<strong>the</strong>r cultural productions, is used in ‘<strong>the</strong> mediation of ruptures of<br />

time and history — to heal disruptions in cultural knowledge, historical memory, and<br />

identity between generations’, people and places. 10 in this way, people can lay claim to<br />

a cultural or ethnic identity through <strong>the</strong> process of using a ‘thing’, whe<strong>the</strong>r it is tapa, <strong>the</strong><br />

haka, or tattoos. The ceremonies tapa mediates, like <strong>the</strong> events for which it serves as a<br />

backdrop, are expressions of connectedness.<br />

Ngatu is also made from syn<strong>the</strong>tic material in transnational Tongan communities.<br />

like <strong>the</strong>ir organic counterparts, syn<strong>the</strong>tic ngatu pieces are used in presentations, as<br />

wrappings, and are also given as gifts. Tongan ngatu artists who produce syn<strong>the</strong>tic<br />

tapa indicate a preference for indigenous materials, but, <strong>the</strong>y say, <strong>the</strong>y will use syn<strong>the</strong>tic<br />

tapa for <strong>the</strong>ir presentations if necessary. As anthropologist roger Neich has argued, for<br />

items of samoan cultural value such as <strong>the</strong> ie toga (cloth for toga) 11 , often <strong>the</strong> aes<strong>the</strong>tic<br />

focus is not only on how <strong>the</strong> item appears, but also what it represents for <strong>the</strong> event or<br />

context in which it mediates <strong>the</strong> ceremony and actions surrounding its presentation or<br />

use. This would explain how Tongan ngatu can be used at a samoan wedding, or a<br />

funeral, or worn by a samoan chief’s daughter in a performance. 12<br />

This is not to say <strong>the</strong> markings on tapa’s paperskin are unimportant, but to highlight<br />

that <strong>the</strong>y coexist with o<strong>the</strong>r dimensions of meaning and interpretation. We seek <strong>the</strong><br />

‘materiality’ of <strong>barkcloth</strong> not only for its markings but also for its qualities as something<br />

made by human hands, a cloth crafted. We seek its power to bring <strong>the</strong> past, people,<br />

history and <strong>the</strong> islands closer — to make <strong>the</strong>m tangible. <strong>barkcloth</strong> connects us in a way<br />

that fascinates, entrances and inspires us.<br />

The meanings of <strong>barkcloth</strong> are as unfixed and changing as <strong>the</strong> identities of <strong>the</strong> people<br />

who use <strong>the</strong>m. if an object’s value is dependent on context we cannot assume a<br />

completeness of cultural transmission despite an increasingly transnational and<br />

interconnected world. When thinking about <strong>barkcloth</strong> we have to consider disjunctions<br />

between <strong>the</strong> spaces where <strong>the</strong>y originate and <strong>the</strong> meanings people give to, and make<br />

through, <strong>the</strong>m in new locations. These circumstances create room for us to celebrate<br />

<strong>barkcloth</strong> as a form of beautifully inscribed paper skin from <strong>Pacific</strong> places distant in time<br />

and location. They also allow us to probe beyond this veneer for a significance that is<br />

deeper and closer to home.<br />

Sean Mallon is senior Curator, <strong>Pacific</strong> Cultures at <strong>the</strong> Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa.<br />

28<br />

Siapo or Ngatu c.1955<br />

Samoa or Tonga<br />

Barkcloth, dye / 176.5 x 84.7cm /<br />

Collected by Sir Guy Richardson<br />

Powles c. 1949-60. Gift of<br />

Michael Powles, 2001. Collection:<br />

Museum of New Zealand Te<br />

Papa Tongarewa<br />

29

Masi (and detail) late 19th century<br />

Fiji<br />

Barkcloth, dye<br />

170.5 x 191cm / A.H. Turnbull<br />

Collection. Presented by <strong>the</strong><br />

Trustees of <strong>the</strong> Turnbull Estate,<br />

1918 / Collection: Museum of New<br />

Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa<br />

eNDNOTes<br />

1 A Maori term for sacred space<br />

or place.<br />

2 Fuataimi literally means ‘to<br />

measure time’, and refers to<br />

a person who guides both<br />

dance and music, conducting<br />

<strong>the</strong> choir as it accompanies<br />

<strong>the</strong> dancers with singing and<br />

movement.<br />

3 ironically, tapa is a samoan<br />

term, which refers to<br />

undecorated <strong>barkcloth</strong>.<br />

4 There are various regional<br />

styles, as well as individual<br />

variations in Fiji.<br />

5 Arjun Appadurai (ed.),<br />

The Social Life of Things:<br />

Commodities in Cultural<br />

Perspective, Cambridge<br />

university Press, Cambridge,<br />

uK, 1986, p.57.<br />

6 Paula Chan Cheuk, interview<br />

with author, Auckland, 1999.<br />

7 Jackie leota-ete, ‘Te Papa<br />

buys unique wedding dress’,<br />

in New Zealand Weddings:<br />

The Complete Guide, starlight<br />

Publications, Christchurch, 1998.<br />

8 robert Friedel, ‘some matters<br />

of substance’, in s lubar<br />

and W David Kingery (eds),<br />

History from Things: Essays on<br />

Material Culture, smithsonian<br />

institution Press, Washington<br />

DC, 1993, p.46.<br />

9 Nina Nawalowalo, brochure for<br />

Vula, The Conch, Wellington,<br />

undated, p.5.<br />

10 Faye Ginsburg, ‘indigenous<br />

media: Faustian contract or<br />

global village?’ in Cultural<br />

Anthropology: Journal for<br />

<strong>the</strong> Society of Cultural<br />

Anthropology, vol.6, no.1,<br />

1991, p.104.<br />

11 Toga is a category of exchange<br />

valuables.<br />

12 roger Neich, ‘Processes of<br />

change in samoan arts and<br />

crafts’, in P.J.C. Dark (ed.),<br />

Development of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Art</strong>s in <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Pacific</strong> [occasional papers],<br />

no.1, <strong>Pacific</strong> <strong>Art</strong>s Association,<br />

National Museum, Wellington,<br />

1983, pp.42–6.<br />

31

32<br />

Marsang<br />

Papua New Guinea, b.1918<br />

Kairak Baining people, East New<br />

Britain Province<br />

Siviritki 1974<br />

Barkcloth, dye, felt pen, natural<br />

fibre, wood and cane / Two<br />

components: 160 x 45.5 x 50cm<br />

(mask); 97cm (fibre) / Collected<br />

by Harold Gallasch, 1974 /<br />

Collection: <strong>Queensland</strong> Museum<br />

The <strong>Pacific</strong> perspective on<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Queensland</strong> Museum:<br />

tradition is present in <strong>the</strong> past and here in <strong>the</strong> present<br />

Imelda Miller<br />

<strong>barkcloth</strong> brings toge<strong>the</strong>r sculpture, music, art, dance, ceremony and story. everything<br />

in <strong>the</strong> ‘<strong>Paperskin</strong>’ exhibition is part of somebody’s story about <strong>the</strong>ir identity and<br />

connection to place. The <strong>barkcloth</strong>s and sculptures have <strong>the</strong>ir own stories, which exist<br />

as <strong>the</strong> past, in <strong>the</strong> present and for <strong>the</strong> future.<br />

in this exhibition we can liken <strong>the</strong> collected <strong>barkcloth</strong>s to a favourite novel — albeit one<br />

that is all middle without <strong>the</strong> beginning or <strong>the</strong> end, or all beginning and end without<br />

<strong>the</strong> middle. Consider that <strong>the</strong> words from a wise storyteller’s mouth become <strong>the</strong> story<br />

written on <strong>the</strong> pages of this book, dance and music become <strong>the</strong> beautiful illustrations,<br />

and <strong>the</strong> ceremony is <strong>the</strong> experience of reading from it. sometimes, we go back to our<br />

favourite pages because something in <strong>the</strong> present that has changed <strong>the</strong> way we think.<br />

When we revisit those pages, <strong>the</strong>re are always more lessons to be learnt about <strong>the</strong><br />

story being told.<br />

Museums collect and preserve evidence in <strong>the</strong> form of objects and information about<br />

<strong>the</strong>m. in doing so, museums also collect parts of culture and build stories. Museum<br />

collections tell us about <strong>the</strong> cultural and physical environments in which objects<br />

originated, <strong>the</strong>ir many uses, and <strong>the</strong> skill, status and mark of <strong>the</strong> maker. As time passes<br />

and attitudes change, more indigenous peoples <strong>across</strong> <strong>the</strong> world are accessing<br />

collections held in institutions to reconnect and bring to life <strong>the</strong>se objects to tell stories<br />

about <strong>the</strong> person, <strong>the</strong> people, <strong>the</strong> community, and <strong>the</strong>ir connection to place in <strong>the</strong> past<br />

and <strong>the</strong> present.<br />

<strong>Queensland</strong> Museum has been collecting for nearly 150 years. its <strong>Pacific</strong> collection has<br />

approximately 26 000 objects and 4000 historical photographs, and its large collection<br />

of <strong>barkcloth</strong>s display a balance between masculine and feminine, old and new.<br />

<strong>Queensland</strong> is strongly connected to <strong>the</strong> people in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pacific</strong>, particularly Melanesia.<br />

Melanesia includes <strong>the</strong> Torres strait islands, Papua New Guinea, <strong>the</strong> solomon islands,<br />

Vanuatu, New Caledonia and Fiji. From 1884, responsibility for british New Guinea<br />

33

ested with <strong>Queensland</strong>, and <strong>the</strong>se links continued after Federation until Papua New<br />

Guinea’s independence in 1975. The associations continue with trade and family<br />

connections between Papua New Guinea and Torres strait islanders, <strong>the</strong> introduction<br />

of south sea islander labour to <strong>the</strong> <strong>Queensland</strong> sugar industry, and <strong>the</strong> new wave of<br />

<strong>Pacific</strong> islanders coming to <strong>Queensland</strong> today. These historical accounts can each be<br />

demonstrated through <strong>the</strong> <strong>Queensland</strong> Museum’s collection.<br />

Tapa, ngatu, kapa, masi, lepau and siapo are names used for <strong>barkcloth</strong> <strong>across</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Pacific</strong>. each place and people has its own unique story for <strong>barkcloth</strong>. some are made<br />

by women, o<strong>the</strong>rs by men, some for cloth and some for masks, some are for everyday<br />

and o<strong>the</strong>rs are for special ceremonies. each piece comes with its own unique story<br />

that has instruction on how it is to be made, how it is to worn, who is to wear it and<br />

<strong>the</strong> power that it holds in <strong>the</strong> ceremony, in dance or as a gift. For this exhibition, <strong>the</strong><br />

Museum has focused on <strong>barkcloth</strong> from Melanesia, and <strong>the</strong> selected objects come<br />

from Papua New Guinea and <strong>the</strong> solomon islands.<br />

A major strength in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Queensland</strong> Museum collection is <strong>the</strong> comprehensive Papuan<br />

ethnographic material, collected by sir William Macgregor in <strong>the</strong> later decades of<br />

<strong>the</strong> nineteenth century. Macgregor had a background in medicine with scientific and<br />

humanitarian interests and he collected this material during his travels in Papua. in<br />

keeping with this vision that this collection would be kept in trust for <strong>the</strong> Papuan people,<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Queensland</strong> Museum repatriated objects back to <strong>the</strong> Papua New Guinea National<br />

Museum between 1983 and 1995, and it was agreed that <strong>the</strong> <strong>Queensland</strong> Museum<br />

would keep a percentage of it. 1 The Macgregor Collection now totals 5627 objects. Not<br />

only aes<strong>the</strong>tically pleasing, <strong>the</strong>se <strong>barkcloth</strong>s also tell us stories about people. in Papua<br />

New Guinea, everyday tapa can include loincloths, wrap around skirts and cloaks.<br />

some groups decorate tapa with painted patterns, as <strong>the</strong> pieces in this exhibition show,<br />

while some attach beads and shells. Worn for ceremonies and rituals, Oro (or Nor<strong>the</strong>rn)<br />

Province is one of <strong>the</strong> most well-known tapa-producing areas of Papua New Guinea. 2<br />

Dance object unknown<br />

Papua New Guinea<br />

Orokolo, Gulf Province<br />

Barkcloth, dye, cane / 28 x 205 x<br />

75.5cm / Collected by S.G.<br />

MacDonell, 1913 / Collection:<br />

<strong>Queensland</strong> Museum<br />

The <strong>barkcloth</strong> from Collingwood bay, Papua New Guinea, was collected by Macgregor<br />

and entered <strong>the</strong> <strong>Queensland</strong> Museum’s collections in 1897.<br />

The designs in <strong>the</strong> Papua New Guinea tapas are somewhat abstract and free-flowing,<br />

similar to those in Vanuatu and in contrast with those from santa Cruz and o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

Polynesian locations. Not much is known about use and manufacture of <strong>barkcloth</strong><br />

(lepau) in santa Cruz. The <strong>barkcloth</strong> from santa Cruz came into <strong>the</strong> <strong>Queensland</strong><br />

Museum’s collections in March 1899. These cloths are known to be worn by men in an<br />

apron-styled fashion, and <strong>the</strong>y have been photographed being worn by important men<br />

like a tall cylinder around <strong>the</strong> top of <strong>the</strong> head. There was an absence of tapa-making<br />

between 1930 and 1970 in santa Cruz. 3 restrictions on practice; political, technical or<br />

environmental changes; <strong>the</strong> movement of people; or a change of interest: <strong>the</strong>se can<br />

all contribute to such absences. however, everybody has <strong>the</strong> culture within <strong>the</strong>m, and<br />

museum collections can help to trigger memories of, emotions about, and connections<br />

between, people and place.<br />

This is happening around <strong>the</strong> world for indigenous cultures, where people are strongly<br />

tied to place. The masks included in ‘<strong>Paperskin</strong>’ are deeply enmeshed in <strong>the</strong> spirit<br />

world of <strong>the</strong> people who made <strong>the</strong>m. For those who believe in <strong>the</strong>se spirits, <strong>the</strong><br />

masks hold strong powers and are respected as part of that world. The eharo masks<br />

represent bush spirits, look like little bush animals and are used during ceremonies<br />

called Hevehe. used to interact with <strong>the</strong> spirit world, sometimes in a humorous way,<br />

and in a time before Christianity, 4 <strong>the</strong> size and diversity of <strong>the</strong>se masks, sometimes<br />

decorated with fea<strong>the</strong>rs and hornbills, reflect <strong>the</strong> diverse Papua New Guinean cultures.<br />

The two-headed crocodile was used in eharo ceremonies, but <strong>the</strong>re is little information<br />

regarding its use or representation. Collected between 1912 and 1914 in <strong>the</strong> Gulf<br />

Province, this beautiful work is made of <strong>barkcloth</strong> wrapped around a cane frame. 5 More<br />

research is required on this piece, but one day, someone somewhere will be reminded<br />

34 35

y this crocodile <strong>barkcloth</strong> of <strong>the</strong>ir connection to people, spirit and place, and <strong>the</strong>y will<br />

be reignited. This is why it is important for Museum collections to be made accessible<br />

to communities through visits, repatriation and exhibitions.<br />

<strong>Pacific</strong> <strong>barkcloth</strong> comes in many forms, shapes and sizes, has many meanings,<br />

and plays an important part in maintaining <strong>the</strong> connections between people and<br />

place. Collections like <strong>the</strong> one held in <strong>Queensland</strong> Museum maintain a connection<br />

between people and place. They connect <strong>the</strong> people who create <strong>the</strong>se works, and<br />

<strong>the</strong> movement that continues between <strong>Pacific</strong> countries and Australia. <strong>barkcloth</strong> is a<br />

beautiful aes<strong>the</strong>tic way to show that <strong>Pacific</strong> people have a presence in <strong>Queensland</strong>’s<br />

history and will continue to have a presence into <strong>the</strong> future.<br />

Imelda Miller is Assistant Curator, Torres strait islander and <strong>Pacific</strong> indigenous studies, <strong>Queensland</strong> Museum.<br />

eNDNOTes<br />

1 Patricia Ma<strong>the</strong>r, A Time for a<br />

Museum: The History of<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Queensland</strong> Museum<br />

1862–1986, <strong>Queensland</strong><br />

Museum, brisbane, 1986,<br />

pp.202–4.<br />

2 roger Neich and Mick<br />

Pendergrast, <strong>Pacific</strong> Tapa,<br />

David bateman, Auckland<br />

Museum, Auckland, 1997, p.133.<br />

36<br />

3 Neich and Pendergrast, p.125.<br />

4 robert l Welsch, Coaxing<br />

<strong>the</strong> Spirits to Dance: <strong>Art</strong> and<br />

Society in Papuan Gulf of New<br />

Guinea [exhibition catalogue],<br />

Nils Nadeau (ed.), hood<br />

Museum of <strong>Art</strong>, hanover, New<br />

hampshire, 2006, pp.23-9.<br />

5 Memoirs of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Queensland</strong><br />

Museum, <strong>Queensland</strong> Museum,<br />

brisbane, vol.2, 1913, pp.9–23.<br />

ABOVE<br />

Mask unknown<br />

Papua New Guinea<br />

Chachet Baining people, East New<br />

Britain Province<br />

Barkcloth, dye, cane / 90 x 52 x<br />

74cm / Collection: <strong>Queensland</strong><br />

Museum<br />

OPPOSITE FROM TOP<br />

Woman from Wanigela, Oro<br />

Province, Papua New Guinea.<br />

Photograph taken by Percy<br />

J. Money c.1900 / Collection:<br />

<strong>Queensland</strong> Museum<br />

Barkcloth (detail) unknown<br />

Papua New Guinea<br />

Collingwood Bay, Oro Province<br />

Barkcloth, dye / 156.8 x 45cm /<br />

Collected by Sir William Macgregor,<br />

1897 / Collection: <strong>Queensland</strong><br />

Museum<br />

37

Plates<br />

38<br />

Marsang<br />

Papua New Guinea b.1918<br />

Kairak Baining people, East New<br />

Britain Province<br />

Mandas mask 1975<br />

Barkcloth, dye, wood, natural fibres,<br />

fea<strong>the</strong>rs / 310 x 74.5 x 59cm /<br />

Collection: Harold Gallasch,<br />

Hahndorf, South Australia<br />

39

40<br />