journal

journal

journal

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

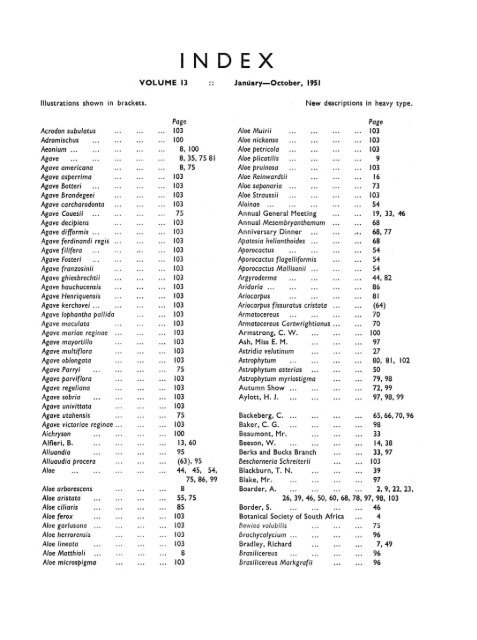

INDEX<br />

VOLUME 13 January—October, 1951<br />

Illustrations shown in brackets. New descriptions in heavy type.<br />

Page<br />

Acrodon subulatus 103<br />

Adromischus 100<br />

Aeonium 8, 100<br />

Agave 8,35,75 81<br />

Agave americana 8,75<br />

Agave asperhma 103<br />

Agave Botteri 103<br />

Agave Brandegeei 103<br />

Agave carcharodonta 103<br />

Agave Couesii 75<br />

Agave decipiens 103<br />

Agave difformis ... ... ... ... 103<br />

Agave ferdinandi regis 103<br />

Agave fitifera ... ... ... ... 103<br />

Agave Fosteri 103<br />

Agave franzosinii 103<br />

Agave ghiesbrechtii 103<br />

Agave hauchucensis 103<br />

Agave Henriquensis ... ... ... 103<br />

Agave kerchovei 103<br />

Agave lophantha pallida 103<br />

Agave maculata ... ... ... 103<br />

Agave mar/ae reginae 103<br />

Agave mayortillo ... ... ... 103<br />

Agave multiflora 103<br />

Agave oblongata 103<br />

Agave Parryi ... ... 75<br />

Agave parviflora 103<br />

Agave regeliana 103<br />

Agave sobria 103<br />

Agave univittata 103<br />

Agave utahensis 75<br />

Agave victoriae reginae 103<br />

Aichryson 100<br />

Alfieri, B 13,60<br />

Alluandia 95<br />

Alluaudia procera (63), 95<br />

Aloe 44, 45, 54,<br />

75, 86, 99<br />

Aloe arborescens 8<br />

Aloe aristata 55,75<br />

Aloe ciliaris 85<br />

Aloe ferox 103<br />

Aloe garlusana 103<br />

Aloe herrorensis 103<br />

Aloe lineata 103<br />

Aloe Matthioli 8<br />

Aloe microspigma 103<br />

Page<br />

Aloe Muirii 103<br />

Aloe nickense 103<br />

Aloe petricola 103<br />

Aloe plicatilis 9<br />

Aloe pruinosa 103<br />

Aloe Reinwardtii 16<br />

Aloe saponaria 73<br />

Aloe Straussii 103<br />

Aloinae 54<br />

Annual General Meeting 19, 33, 46<br />

Annual Mesembryanthemum 68<br />

Anniversary Dinner 68, 77<br />

Apatesia helianthoides 68<br />

Aporocactus 54<br />

Aporocactus flagelliformis 54<br />

Aporocactus Mallisonii 54<br />

Argyroderma 44, 82<br />

Aridaria 86<br />

Ariocarpus 81<br />

Ariocarpus fissuratus cristata (64)<br />

Armatocereus 70<br />

Armatocereus Cartwrightianus 70<br />

Armstrong, C. W 100<br />

Ash, Miss E. M. 97<br />

Astridia velutinum 27<br />

Astrophytum 80, 81, 102<br />

Astrophytum aster/as 50<br />

Astrophytum myr/ostigma 79,98<br />

Autumn Show 72,99<br />

Aylott, H. J 97,98,99<br />

Backeberg, C 65,66,70,96<br />

Baker, C. G 98<br />

Beaumont, Mr. 33<br />

Beeson, W 14,38<br />

Berks and Bucks Branch 33,97<br />

Beschorneria Schreiterii 103<br />

Blackburn, T. N 39<br />

Blake, Mr 97<br />

Boarder, A 2,9,22,23,<br />

26, 39, 46, 50, 60, 68, 78, 97, 98, 103<br />

Border, S. 46<br />

Botanical Society of South Africa ... 4<br />

Bowiea volubilis 75<br />

Brachycalycium 96<br />

Bradley, Richard 7,49<br />

Brasi/icereus 96<br />

Brasilicereus Markgrafii 96

Page<br />

Bromeliads ... 71<br />

Bruce, Mrs. P. M 102<br />

Bryophyllum 7, 100, 102<br />

Bryophyllum tubiflorum 26<br />

Bulbine annua 75<br />

Bulbine semibarbata 75<br />

Buxbaum, Professor 4,45,56<br />

Cacti in Switzerland 80<br />

Cactus icosagonus ... 70<br />

Cactus lanatus 70<br />

Cactus Cultural Notes 78<br />

Caralluma 5<br />

Caralluma mammillaris 5(11)<br />

Carey, L. H. W 95<br />

Carnegiea gigantea 74<br />

Carpanthea pomeridiana 68<br />

Carpobrotus ... 75<br />

Cephalocereus senilis 79<br />

Cephalophyllum 86<br />

Cereeanae 98, 99<br />

Ceropegia stapeliiformis 103<br />

Cereus 40,71,72,75,<br />

81,95<br />

Cereus flagelliformis 80<br />

Cereus Mallisonii 54<br />

Cereus marginatus (36)<br />

Cereus Maynardii 54<br />

Cereus phaeacanthus 96<br />

Cereus serpens 71<br />

Cereus Smithii 54<br />

Chamaecereus Silvestrii 9,51,79<br />

Chamaeg/'gas intrepidens 69, 72, 81<br />

Cheiridopsis 82, 86<br />

Cheiridopsis candissima 5<br />

Chiastophyllum 75<br />

Churchman, Mr. 33<br />

Cleistocactus 71<br />

C/e/stocactus anguineus 71<br />

Cleistocactus Straussii 98<br />

Coarctata Group {Haworthia) ... 16, 17<br />

Collings, P. V. 14,44,46,50<br />

79, 97, 98, 99<br />

Comments on Spines 21<br />

Compositae 58,75<br />

Conophytum 10,15,82<br />

Conophytum albescens 15<br />

Conophytum altile 15<br />

Conophytum bilobum 10, 15<br />

Conophytum calculum 15<br />

Conophytum cauliferum 10, 15<br />

Conophytum cordatum 15<br />

Conophytum corniferum 10<br />

Conophytum frutescens 10, 15<br />

Conophytum globosum 15<br />

Conophytum gratum 15<br />

Page<br />

Conophytum Julii 15<br />

Conophytum Meyeri 10, 15<br />

Conophytum minutum 15<br />

Conophytum obcordellum 15<br />

Conophytum obmetale 15<br />

Conophytum pallidum 15<br />

Conophytum pisinnum 15<br />

Conophytum Purpusii 15<br />

Conophytum ramosus 10<br />

Conophytum saxetanum 15<br />

Conophytum truncatellum 15<br />

Conophytum Wettsteinii 15<br />

Cooke, Captain H. J 31,46, 101<br />

Coryphantha 7,43,75,96<br />

Coryphantha radians 79<br />

Coryphanthanae 4, 20, 21<br />

98,99<br />

Cotyledon 44, 75, 99,<br />

100<br />

Cotyledon grandiflora 73<br />

Cotyledon orbiculata 9, 73<br />

Court, F. M 33<br />

Covent Garden Succulent Corner ... 19<br />

Cowell, John 49<br />

Crassula 44, 75, 99,<br />

100<br />

Crassula arborescens 100<br />

Crassula Archeri 100<br />

Crassula arta 100<br />

Crassula Barklyii 100<br />

Crassula coccinea 100<br />

Crassula Cooperi 52, 100<br />

Crassula corymeulosa 100<br />

Crassula deceptrix 100<br />

Crassula falcata 52<br />

Crassula farinosa 100<br />

Crassula Gillii 100<br />

Crassula hemisphaerica 100<br />

Crassula Hookeri 100<br />

Crassula impressa 100<br />

Crassula Justus corderoy 52,100<br />

Crassula lanuginosa 100<br />

Crassula lycopodioides 9, 100<br />

Crassula orbiculata 100<br />

Crassula Pearsonii 100<br />

Crassula perforata 100<br />

Crassula pyramidalis 100<br />

Crassula rosu\aris 100<br />

Crassula rupestris 100<br />

Crassula Schmidtii 9,100<br />

Crassula sarcocaulis 55, 74, 75,<br />

83, 100<br />

Crassula socialis 100<br />

Crassula tecta 100<br />

Crassula teres 100

Page<br />

Crassula tetragona 100<br />

Crassuhceae 54, 75, 95,<br />

100<br />

Cristate, Five Branched (65)<br />

Crossing a River ... (65)<br />

Cryophytum 75<br />

Cultural Notes 2,26,50,68<br />

Cultivation of Succulents 82<br />

Dactylopsis digitata 15<br />

Dale, W. 100<br />

Darrah Collection 81<br />

Delosperma 86<br />

Denton, W 46, 68, 82,<br />

95, 98, 99<br />

Diacanthium (Euphorbia) 4<br />

Didymaotus lapidiformis 15<br />

Dinteranthus 31<br />

Dinteranthus microspermus 31<br />

Dinteranthus van Zijlii 29<br />

Do/ichothele 43<br />

Dolichothele longimamma 79<br />

Dorotheanus 68, 75<br />

Dorotheanus bellidiformis (66), 68<br />

Dorotheanus luteus 68<br />

Dorotheanus oculatus 68<br />

Drosanthemum 86<br />

Duvalia 5<br />

Dyke, Mrs 97<br />

Dyke, Miss J 97<br />

Eastbourne Succulents 8(14)<br />

Eberlanzia spinosa 103<br />

Bcheveria 9, 54, 74,<br />

75,99, 100<br />

Echeveria farinosa 9<br />

Echeveria metallica 102<br />

Ech/nocactus 97,98,99<br />

Echinocactus Grusonii 2, 78, 79<br />

Echinocereeanae 98, 99<br />

Echinocereus 50,75, 102<br />

Echinocereus Fendleri 50<br />

Echinocereus procumbens 79<br />

Echinocereus pulchellus (63)<br />

Echinopsis 20, 55<br />

Echinopsis Eyriesii ... 79<br />

Echinopsis multiplex 9<br />

Ech/nops/s violacea ... (64)<br />

Editorial 1,25,49,77<br />

Edwards, A. J 14, 18, 31,<br />

46, 68, 77, 98, 99<br />

Electricity in the Greenhouse ... 18<br />

Elkan, Dr. E 37<br />

Epiphyllum 25,55,74<br />

Epiphyllum Ackermannii 79<br />

Epithelantha micromeris 2,79<br />

Page<br />

Espostoa lanata 71<br />

Espostoa sericata (65)<br />

Euechinocactanae ... 4<br />

Euphorbia 30, 44, 73,<br />

74, 81, 83, 98, 99, 100, 102<br />

Euphorbia bupleurifolia 83<br />

Euphorbia canadensis 4, 83<br />

Euphorbia caput medusae 59,73<br />

Euphorbia cereiformis 83<br />

Euphorbia coerulescens 73<br />

Euphorbia Dregeana 73<br />

Euphorbia gorgonis 83<br />

Euphorbia Ledienii 73<br />

Euphorbia Morinii ... ... ... 83<br />

Euphorbia neriifolia 4<br />

Euphorbia Neumanniana 83<br />

Euphorbia nivulia 4<br />

Euphorbia obesa 83<br />

Euphorbia pentagona 4<br />

Euphorbia pugniformis 83<br />

Euphorbia Reinhardtii 4<br />

Euphorbia Royleana ... ... ... 4(11)<br />

Euphorbia splendens 83<br />

Euphorbia squarrosa 83<br />

Euphorbiaceae 40,75<br />

Evans, S. M 103<br />

Exploration Trip to Northern Peru ... 70<br />

Faucaria 51, 99<br />

Fenestraria 82<br />

Ferocactus latispinus 78<br />

Ferocactus longihamatus (36)<br />

Fiedler, S. G 19<br />

Furcreae Roezlii 103<br />

Gasteria 9,54,86,99<br />

Gasteria gigantea 103<br />

Gasteria nitens ... 103<br />

Gasteria wroomii 103<br />

Gates, Howard E. 44, 64<br />

Geyer, Dr. A. L 19, 28, 31<br />

Gibbaeum 15, 82, 86<br />

Gilbert, C. E. L. 103<br />

Glauca group (Haworthia) ... ... 16<br />

Glauser, Emil 80<br />

Glottiphyllum Muihi 103<br />

Glottiphyllum Nellii 103<br />

Glottiphyllum oligocarprea 103<br />

Glottiphyllum platycarpin 103<br />

Glottiphyllum Salmii 103<br />

Green, G. G 10, 33, 34,<br />

35, 39, 58, 66<br />

Groth, I. 36<br />

Grow, do not Keep Cacti 22<br />

Growing Succulents Outdoors ... 74

Page<br />

Gymnocalycium 96<br />

Gymnocalycium multiflorum 79<br />

Gymnocalycium platense (14)<br />

Gymnanthocereus microspermus ... 72<br />

Gymnolobiviae ... ... ... ... 96<br />

Haage, jr., F. A. 63,64<br />

Haageocereus ... ... 72<br />

Haageocereus versicolor 72<br />

Hall, H 5,11,59,73<br />

Hamatocactus setispinus : (14), 79<br />

Harle, K. W 39, 44, 46,<br />

95<br />

Haworth, Adrian 7<br />

Haworthia 9, 16, 86,<br />

98,99<br />

Haworthia attenuata 16<br />

Haworthia attenuata caespitosa ... 16<br />

Haworthia Blackburniae ... ... 16<br />

Haworthia Chalwinii 17<br />

Haworthia cuspidata 16<br />

Haworthia cymbiformis 16<br />

Haworthia fasciata 16<br />

Haworthia graminifolia 16<br />

Haworthia Greenii 17<br />

Haworthia limifolia 16<br />

Haworthia margaritifera 16<br />

Haworthia mucronata 16<br />

Haworthia nigra 16<br />

Haworthia planifolia 16<br />

Haworthia Reinwardtii 16, 17, 86<br />

Haworthia Reinwardtii adelaidensis ... 17<br />

Haworthia Reinwardtii archibaldiae ... 17<br />

Haworthia Reinwardtii bellula 17<br />

Haworthia Reinwardtii brevicula ... 17, 86<br />

Haworthia Reinwardtii chalumnensis ... 17, 86<br />

Haworthia Reinwardtii committeesensis 17, 86<br />

Haworthia Reinwardtii conspicua ... (12), 17<br />

Haworthia Reinwardtii diminuta ... (13), 17<br />

Haworthia Reinwardtii faltax (12), 17<br />

Haworthia Reinwardtii grandicula ... 17, 86<br />

Haworthia Reinwardtii hunstdriftensis 17, 86<br />

Haworthia Reinwardtii kafprdriftensis (12), 17, 86<br />

Haworthia Reinwardtii major (12), 16, 17<br />

Haworthia Reinwardtii minor (13), 17<br />

Haworthia Reinwardtii olivacea ... 17<br />

Haworthia Reinwardtii peddiensis ... 17,86<br />

Haworthia Reinwardtii pseudocoarctata 17<br />

Haworthia Reinwardtii riebeekensis ... 17, 86<br />

Haworthia Reinwardtii tenuis (13), 17<br />

Haworthia Reinwardtii triebneri ... 17<br />

Haworthia Reinwardtii valida 17, 86<br />

Haworthia Reinwardtii zebrina ... 17<br />

Haworthia tessellata 16, 86<br />

Haworthia truncata 16<br />

Page<br />

Haworthia viscosa 16<br />

Heliaporus Smithii 54<br />

Heliocereus 54, 55<br />

Heliocereus amecamensis 55<br />

Heliocereus speciosus 54<br />

Helioselenius Maynardtii 54<br />

Hepworth, E 39<br />

Hermann, J. ... ... 17<br />

Herre, H 45,66,68<br />

Hesperaloe parviflora 103<br />

Hewitt, G. D 95<br />

Homalocephala texensis 103<br />

Hood/o 30<br />

Howard, Mrs. Pryke 98,99<br />

Hurford, Mrs. G. N 99, 103<br />

Hylocereus 72<br />

Hylocereus peruvianus 72<br />

Hylocereus triangularis 34 (35)<br />

Hymenogyne conica 68<br />

Imitaria Muirii 15<br />

Jacobs, Dr 97<br />

Jacobsen, H 45, 59, 69,<br />

102<br />

Janse, J. H 4,11<br />

Jensen, Miss 97<br />

Judd, H. N 98<br />

Kalanchoe 95, 100<br />

Kalanchoe beharensis 81<br />

Kalanchoe bentii 54<br />

Kalanchoe diagremontianum 9<br />

Kalanchoe flammea 54<br />

Kalanchoe x kewensis 54<br />

Kidd, Miss M. Maytham 4,45<br />

Kleinia 7, 9, 58, 67<br />

Kleinia articulata 9<br />

Kleinia neriifolia (38)<br />

Kleinia pendula 67<br />

Kleinia repens 9, 73<br />

Kleinia tomentosa 67<br />

Krainz, H 80<br />

Label, The Ideal 32<br />

Lady shows her Cups ! 59<br />

Lamb, E. 97<br />

Lampranthus aurantiacus 103<br />

Large plant portage (66)<br />

Lawrence, Miss M 46<br />

Lemaireocereus pruinosus 27, 78, 79<br />

Lenophyllum 100<br />

Leuchtenbergia principis 99<br />

Lewisia 75<br />

Liliaceae .. 75, 86

Page<br />

Lithops 10, 19, 28,<br />

39, 44, 51, 67, 69, 82, 102<br />

Lithops bella 67, 82<br />

Lithops brevis 29<br />

Lithops Bromfieldii 28,29<br />

Lithops chrysocephala 29<br />

Lithops Comptonii 28<br />

Lithops dendritka 29<br />

Lithops Dinteri 29<br />

Lithops divergens 30<br />

Lithops Dorotheae 28,29<br />

Lithops Fulleri 28,29<br />

Lithops fulviceps 29<br />

Lithops Geyeri 29<br />

Lithops Gulielmi 28<br />

Lithops Helmuti 29<br />

Lithops Herrei 29<br />

Lithops insularis 28<br />

Lithops Jocobseniana 29<br />

Lithops karasmontana 29,82<br />

Lithops kuibisensis 29<br />

Lithops kunjasensis 28<br />

Lithops lateritiq 29<br />

Lithops Lericheana 29<br />

Lithops Lesliei ... 28,29,82<br />

Lithops marmorata 29<br />

Lithops Marthae 29<br />

Lithops Mennellii 28,29<br />

Lithops Meyeri 29<br />

Lithops mickbergensis 29<br />

Lithops Nelii 28<br />

Lithops olivacea 28<br />

Lithops opalina 29<br />

Lithops Otzeniana 29<br />

Lithops pseudotruncatella 28,29,82<br />

Lithops rugosa 28<br />

Lithops Schwantesii 28,39<br />

Lithops summitata 29<br />

Lithops terricolor 28, 82<br />

Lithops Triebneri 28<br />

Lithops turbiniformis ... 29<br />

Lithops urikosensis 29<br />

Lithops van Zijlii 28, 29<br />

Lithops verruculosa 28<br />

LITHOPS WERNERI 29,59,69<br />

Lists received 39<br />

Lobivio 16,81,96<br />

Lobivia Backebergii 79<br />

Lobivia famatimensis cinnabarini ... (13)<br />

Lobivia Nealeana 96<br />

Lobivia Pentlandii 51<br />

Lobivio rebutioides 96<br />

Lophophora 7,95<br />

Lophophora Williamsii 101<br />

Page<br />

Machaerocereus gummosus (64)<br />

Malacocarpus vorwerkianus 79<br />

Mammillaria 3, 16, 21,<br />

22, 26, 27, 42, 50, 51 (60), 78, 97, 102<br />

Mammillaria amoena 42<br />

Mammillaria angularis ... ... 42,43, 44<br />

Mammillaria arietina 43<br />

Mammillaria Blossfeldiana 51<br />

Mammillaria bocasana 27, 50, 51,<br />

78, 79, 98, 102<br />

Mammillaria Bockii 44<br />

Mammillaria bogotensis 102<br />

Mammillaria Boucheana 42<br />

Mammillaria centricirrha 42, 43, 44<br />

Mammillaria ceratophora 43<br />

Mammillaria cirrhifera ... 43<br />

Mammillaria cirrosa 43<br />

Mammillaria columbiana 78<br />

Mammillaria conopsea 44<br />

Mammillaria decipiens ... 43<br />

Mammillaria deflexispina 44<br />

Mammillaria denudata 50<br />

Mammillaria destorum 42<br />

Mammillaria de tampico 42<br />

Mammillaria diacantha ... ... 43<br />

Mammillaria diadema 44<br />

Mammillaria divaricata 43,44<br />

Mammillaria divergens 43<br />

Mammillaria dolichocentra 43<br />

Mammillaria Bhrenbergii 44<br />

Mammillaria elegans (38), 102<br />

Mammillaria falcata 44<br />

Mammillaria Foersteri 44<br />

Mammillaria formosa 43<br />

Mammillaria fulvispina 43<br />

Mammillaria Gebweileriana ... ... 44<br />

Mammillaria gladiata 43<br />

Mammillaria glauca ... 44<br />

Mammillaria globosa 42<br />

Mammillaria gracilis ... 20<br />

Mammillaria grandicornis ... ... 44<br />

Mammillaria grandidens 43<br />

Mammillaria Guilleminiana ... ... 43<br />

Mammillaria Haageana 43<br />

Mammillaria Hahniana (64)<br />

Mammillaria Herrerae 102<br />

Mammillaria hexacantha 43,44<br />

Mammillaria Heyderi 102<br />

Mammillaria hystrix ... ... ... 43<br />

Mammillaria Jorderi 43<br />

Mammillaria Krameri 44<br />

Mammillaria Kraussei 44<br />

Mammillaria Kunzeana 50<br />

Mammillaria lactescens 44<br />

Mammillaria latimamma 43

Page<br />

Mammillaria Lehmannii 43<br />

Mammillaria longiflora 50<br />

Mammillaria longispina 43<br />

Mammillaria macracantha 43<br />

Mammillaria magnimamma 22, 42, 43<br />

Mammillaria mammillaris 78<br />

Mammillaria megacantha ... ... 43<br />

Mammillaria microceras 44<br />

Mammillaria Montsii 43<br />

Mammillaria Moritziana 43<br />

Mammillaria multiceps 51<br />

Mammillaria Neumanniana 44<br />

Mammillaria Nordmannii 43<br />

Mammillaria obconella 43<br />

Mammillaria obscura 43<br />

Mammillaria pachythele 43<br />

Mammillaria Pazzanii ... ... 43<br />

Mammillaria pentacantha 43<br />

Mammillaria picta ... ... ... 50<br />

Mammillaria polyedra 43<br />

Mammillaria polygona ... ... ... 43<br />

Mammillaria polytricha 43<br />

Mammillaria posteriana 43<br />

Mammillaria prolifera 51<br />

Mammillaria pulchra 43<br />

Mammillaria pygmaea 50<br />

Mammillaria recurva 44<br />

Mammillaria rhodantha 50,79<br />

Mammillaria Schiedeana 43<br />

Mammillaria Schelhasei 50<br />

Mammillaria Schmidtii 44<br />

Mammillaria sempervi'vi 43<br />

Mammillaria sericata 43<br />

Mammillaria spinosoir 43<br />

Mammillaria subcurvata 43<br />

Mammillaria subpolyedra 43<br />

Mammillaria tetracantha 43, 79<br />

Mammillaria tetracentra 44<br />

Mammillaria tolimensis longispina ... (36)<br />

Mammillaria triacantha 44<br />

Mammillaria uberimamma 43<br />

Mammillaria uncinata 102<br />

Mammillaria valida 43<br />

Mammillaria versicolor 43<br />

Mammillaria Viereckii 102<br />

Mammillaria viridescens 43<br />

Mammillaria viridis 44<br />

Mammillaria Wildiana 22, 50, 51<br />

Mammillaria Zooderi 43<br />

Mammillaria Zuccariniana 43<br />

Manfreda maculosa 103<br />

Mansfield, The Earl of 46<br />

Mediolobivia 96<br />

Melocactus 72<br />

Mesembryanthemaceae 45,68<br />

Page<br />

Mesembryanthemum 10, 15, 73,<br />

79,81,87,97,98,99, 100<br />

Mesembryanthemum australe 102<br />

Mesembryanthemum criniflorum ... 68<br />

Mickelson, Mrs. 50<br />

Milton, S. F 97<br />

Monanthes 100<br />

Morgenstern, K. D 79<br />

Muiria hortenseae 86<br />

Murray, Mrs. J. E 98<br />

Myrtillocactus grandiareolis (37)<br />

Naylor, S 20,21,56<br />

Neale's Photographic Plates 4<br />

Neale, W. T. and Co. Ltd 39<br />

Neave, Miss J. 99<br />

Neomammillaria 103<br />

Neoraimondia gigantea 72<br />

Noakes, Captain E. J. W 64<br />

Nolina longiflora 103<br />

Nopalxochia 55<br />

North Kent Branch 97<br />

Notes on Euphorbia 4<br />

Notocactus concinnus 79<br />

Notocactus Haselbergii 50<br />

Notocactus mammulosus ... ... 50<br />

Opuntia 7, 20, 25,<br />

26,74,75,81, 102<br />

Opuntia basilaris 86<br />

Opuntia Burbank special 74<br />

Opuntia cantabrigiensis 75<br />

Opuntia castillae 74<br />

Opuntia Ellisiana ." 74<br />

Opuntia ficus indica 74<br />

Opuntia fragilis 86<br />

Opuntia imbricata 102<br />

Opuntia leucotricha 86<br />

Opuntia lurida 102<br />

Opuntia microdasys 9, 79<br />

Opuntia Rafinesquei 55 (63), 75,<br />

Opuntia robusta 75<br />

Opuntia subulata (37)<br />

Opuntieae 57<br />

Orostachys 75, 100<br />

Pachycereus Pringlei (64)<br />

Pachyphytum 9, 54, 100<br />

Pam, Major A 39<br />

Pelargonium ... 102<br />

Pereskia 20, 56, 57<br />

Pereskia grandiflora 81<br />

Pereskieae 57<br />

Phy//ocactus 25,80<br />

95

Page<br />

Phytolaccaceae 56<br />

Piaranthus 5<br />

Pilocereus 71<br />

Pilocereus Tweedyanus ... 71,72<br />

Pizarro Monument (66)<br />

Platyopuntia 97<br />

Pleiospilos 15, 52, 69,<br />

82, 101, 102<br />

Pleiospilos Bolusii 101<br />

Pleiospilos Hilmari 83<br />

Pleiospilos Nelii 69,101<br />

Pleiospilos simulans 101<br />

Polygonae (Euphorbia) 4<br />

Poore, Miss D. M 17,46,99<br />

Portulaca 7,54,75<br />

Portulaca grandiflora 52, 53, 54<br />

Powell, J 38<br />

Pullen, S. J 46, 98, 99,<br />

100<br />

Punctillaria 101<br />

Puya 39<br />

Rebutia 50,96<br />

Rebutia miniscula 51<br />

Rebutia senilis 79<br />

Rebutia Steinbachii 96<br />

Reinwardtii group (Haworthia) ... 16<br />

Reviews 45<br />

Reynolds, G. W 45<br />

Reynolds, L. J 98<br />

Rhinephyllum Broomii 83<br />

Rhipsalis 74<br />

Rosularia 75, 100<br />

Round the Shows 97<br />

Rowland, C. H. 46<br />

Rowley, Gordon D 6, 40, 52,<br />

74, 84<br />

Ruschia 86<br />

Ruschia impressa 84<br />

Ruschia nonimpressa 84<br />

Ruschia uncinata 55, 75, 84<br />

Salicornia 102<br />

Schellenberg, Mr 80<br />

Schmoll, F 36<br />

Schwantes, G 69<br />

Scientific Approach to Succulents ... 6,40,52,84<br />

Sedum 75, 100<br />

Sedum acre 75,84<br />

Sedum album 75<br />

Sedum Nussbaumeri 102<br />

Seedlings in trough (60)<br />

Selenicereus 7, 54, 55<br />

Selenicereus grandiflorus 54<br />

Sempervivella 75, 100<br />

Page<br />

Sempervivum 75,81, 100<br />

Senecio 58<br />

Senecio fulgens 67<br />

Senecio longifolius 67<br />

Senecio Medley-woodii 58(66)<br />

Senecio pyramidatus ... 67<br />

Senecio scaposus 58<br />

Senecio stapeliiformis 58,67<br />

Senecio vestita 58<br />

Seticereus Humboldtii 71<br />

Seticereus icosagonus ... 71<br />

Sherman Hoyt Trophy 103<br />

Shurly, E. 8,9,21,22,<br />

38, 42, 80<br />

Shurly, Mrs. D. F 98,99<br />

Simms, M 97<br />

Smuts, Field Marshal 45<br />

Spines 20, 56<br />

Sparks, Miss 97<br />

Stapelia 5,7,28,31,<br />

40, 44, 75, 83<br />

Stapelia hirsuta 28<br />

Stapelia nobilis (38)<br />

Stemless Mesembryanthemum 10<br />

Stillwell, Mrs. M 33, 59, 69,<br />

79, 97, 98, 99, 101<br />

Stillwell's, Mrs. Propagator (14)<br />

Stringer, H 32<br />

Strombocactus disciformis (37)<br />

SULCOREBUTIA 96<br />

Sulcorebutia Steinbachii 96<br />

Summer Show 98<br />

Synadenium Crantii 102<br />

Tillandsia 71<br />

Titanopsis 82,83<br />

Trichocereus pachanoi 71<br />

Tnchocereus Scm'ckendantz/i 75<br />

Trichodiadema 86<br />

Triebner, W 69<br />

Uitewaal, A. J. A 12, 13, 16<br />

Umbilicus 75, 100<br />

Variability within Haworthia Reinwardtii 16<br />

Volk, Professor Dr. O. H 45<br />

Walden, K. H 46, 98, 99,<br />

102<br />

Wells, Mrs. J. Luty 97, 98, 99<br />

West, R. H 98,99<br />

Wheldon, and Wesley Ltd 39<br />

Windsor Show 97<br />

Winter Care of Cacti 9

Page<br />

Winter, H 39,64<br />

Xantholithops 69<br />

Yucca 39<br />

Yucca gloriosa 74<br />

Page<br />

Yucca Whipplei 74<br />

Zurich Collection 80<br />

Zygococtus 41<br />

Zygocactus truncatus 79

THE<br />

CACTUS<br />

AND SUCCULENT<br />

JOURNAL<br />

OF GREAT BRITAIN<br />

Established 1931<br />

Vol. 13 JANUARY 1951 No. 1<br />

Contents<br />

PAGE<br />

Editorial I<br />

Cultural Notes 2<br />

Notes on Euphorbias 4<br />

Caralluma mammillaris 5<br />

The Scientific Approach to Succulents 6<br />

Eastbourne Succulents 8<br />

Stemless Mesembryanthemums 10<br />

Haworthia Reinwardtii 16<br />

Electricity in the Greenhouse 18<br />

Spines 20<br />

Grow, do not keep Cacti 22<br />

Published Quarterly by the Cactus and Succulent Society of Great<br />

Britain at 7 Deacons Hill Road, Elstree, Herts.<br />

Strange tbe Printer Ltd., Eastbourne and London. L&637

Branches<br />

President : Rt. Hon. The Earl of Mansfield<br />

Vice-Presidents : Captain H. J. Dunne Cooke, K. W. Harle<br />

COUNCIL:<br />

A. J. EDWARDS, A.M.Tech.l.(Gt. Bt.) W. DENTON, B.E.M.<br />

H. J. AYLOTT Chairman. Miss E pgRGUSSON KELLY<br />

A. BOARDER E. SHURLY, F.C.S.S.<br />

P. V. COLLINGS K. H. WALDEN<br />

Secretary : C. H. Rowland, 9 Cromer Road, Chadwell Heath, Essex.<br />

Treasurer : Miss D. M. Poore, 48 The Mead, Beckenham, Kent.<br />

Ed/tor : E. Shurly, 7 Deacons Hill Road, Elstree, Herts.<br />

Librarian : P. V. Callings, St. John, Northumberland Road, New Barnet, Herts.<br />

Exchanges : A. Boarder, Marsworth, Meadway, Ruislip, Middlesex.<br />

Assistant Secretary : K. H. Walden, IS2 Ardgowan Road, Catford, London, S.E.6.<br />

Meeting Place : New Hall, Royal Horticultural Society, Vincent Square, London, S.W.I.<br />

1951<br />

February 6th, 7 p.m. Annual General Meeting.<br />

Subscription : 21/- per annum<br />

SOCIETY NEWS<br />

March 20th, 6 p.m. Dr. A. L. Geyer : Lithops.<br />

April 3rd, 7 p.m. Covent Garden Succulent Corner.<br />

Berks & Bucks : Secretary : Mrs. M. Stillwell, 18 St. Andrews Crescent, Windsor.<br />

West Kent : Secretary : J. H. Grimshaw, 67 Masons Hill, Bromley, Kent.<br />

North Kent : Secretary : S. F. Milton, 75 Portland Avenue, Gravesend.<br />

Back Numbers of the Journal<br />

The following are still available :—<br />

Volume 2 Parts 1, 3 and 4.<br />

3 Parts 3 and 4.<br />

,, 4 Complete.<br />

„ 5 Parts 1, 2 and 3.<br />

„ 6 Parts I and 2.<br />

„ 7 Parts 3 and 4.<br />

8, 9, 10 and 11 complete.<br />

Prices : Volumes 12/- each.<br />

Single parts 3/- each.<br />

Post free from The Editor, 7 Deacons Hill Road, Elstree, Herts.

THE<br />

CACTUS<br />

AND SUCCULENT<br />

JOURNAL<br />

OF GREAT BRITAIN<br />

ESTABLISHED 1931<br />

Vol. 13 JANUARY, 195! No.<br />

EDITORIAL<br />

In the course of my business I have occasion to read through the names and details of new limited companies.<br />

I recently saw one had been formed in the Midlands, with considerable capital, for the growing of cacti and<br />

succulents.<br />

I have also seen, in florist shops, crates marked with names of many growers and it is obvious their number<br />

increases almost, one might say, daily. It is a repetition of the early thirties. Before founding our society I launched<br />

a campaign in the gardening papers by letters and articles and got in touch with existing collectors and then called<br />

the meeting at St. Bride's Institute. The existing collectors were, directly or indirectly, the result of similar work<br />

by Walton, the Midland dealer, in the latter years of the nineteenth century. The only dealers, so far as I am aware,<br />

were Endean and Neales, both of whom gave me generous assistance in the preliminary work. The campaign<br />

and the formation of the society created public interest and articles and cartoons appeared even in our national<br />

Press and many became aware of the good market for cacti and succulents. Of later years the tendency has been<br />

to grow for bulk buyers and rather neglect the ordinary collector whose wants were less profitable to satisfy.<br />

1 am just wondering whether this helps us. It is perfectly true that several members commenced with the<br />

purchase of one of these bulk plants, but I wonder how many more lost their interest when they lost plants through<br />

ignorance ? I believe it is correct to say that for every one that survived, thousands were lost. Obviously, the<br />

remedy is to provide the purchasers with cultivation details, but distribution presents a problem. The Society<br />

helps where it is known, but notwithstanding the years we have been established, thousands owning cacti do not<br />

know of our existence.<br />

We cannot complain of the business instincts of growers, most of whom generously support the various<br />

societies, but I suggest it might be of more service to take steps to ensure the survival of these plants rather than<br />

benefit, unwillingly probably, from repeat sales for those that are lost. There is an opening for somebody to cater<br />

for collectors exclusively.<br />

We are modestly rather proud of the Journal, so it is with gratitude that we read in the July, I9S0, issue of<br />

" Fuaux Herbarium Bulletin " (Australia)—" It is a most valuable Journal, maintaining what is probably the highest<br />

technical standard of any similar publication in the English language."<br />

If you have not already remitted your subscription for 1951, please do so without delay to the Hon. Treasurer,<br />

Miss D. M. Poore, 48 The Mead, Beckenham, Kent, so that the 1951 programme can be completed. It also helps<br />

our honorary treasurer considerably and saves correspondence and expense.

2 THE CACTUS AND SUCCULENT January, 1951<br />

CULTURAL NOTES<br />

By A. BOARDER<br />

The next three months are the very important ones as far as the cultivation of Cacti and other Succulents<br />

are concerned. During this time all plants should be repotted and seed should be sown. I consider that the first<br />

task is the preparation for potting. There are two schools of thought concerning the advisability of repotting<br />

each year. The old timers are often of the opinion that repotting should be reduced to a minimum and if we take<br />

notice of some of the old directions given in some books we cannot expect our plants to flower until the plant is<br />

pot bound. I often see collections of such growers and the very look of the plants tells me at once that the plants<br />

have not grown for years and are not likely to do so unless they are repotted. The newer school recognise the<br />

fact that Cacti are, after all, just rather unusual plants and are not something apart. That Cacti will flourish and<br />

bloom if they get proper treatment is apparent to anyone who takes the trouble to treat the Cacti in a reasonable<br />

manner considering that they are living plants which require very much the same in the way of nourishment as<br />

for instance, a chrysanthemum.<br />

To really understand their requirements it may be useful here if I run through briefly the necessary essentials<br />

for healthy growth. All plants require in fair quantities, nitrogen, phosphorus, sulphur, potassium, calcium and<br />

magnesium. Also, but in smaller amounts, they need iron, manganese, sodium, chlorine and silicon, and then<br />

minute particles of the so-called trace elements such as, copper, zinc, boron, etc. In addition a large amount of<br />

hydrogen and oxygen are taken in by the roots of the plant and carbon is obtained from the atmosphere. There<br />

is no need for me to go over the complicated methods employed by the plants to obtain these substances but the<br />

mention of them alone will serve to bring home the point that it is absolutely impossible for the required amounts<br />

of these elements to remain in a small pot of soil which has been watered fairly frequently for a year or two. In<br />

a pot which has considerable drainage, as is so often recommended, it can be imagined how easily the repeated<br />

waterings can wash the elements from the pot. This all leads up to the fact that I consider it is absolutely necessary<br />

to repot all Cacti at least once each year.<br />

There is another very good reason for repotting and that is the prevention of root pests. The root bug is a<br />

pest which resembles the mealy bug but which only attacks the roots of a plant. Unless a plant is removed from<br />

its pot it is often impossible to know whether a plant is so attacked or not. I have found from experience that root<br />

bug thrives in root-bound pots which have been left undisturbed for a few years. I am quite sure that many<br />

readers will remember turning a plant from a pot after it has been there for say three years and then finding that<br />

all the roots appear dead and the soil, if there is any left, is in a very poor condition and does not contain any<br />

nourishment. I have given, in previous articles, the mixture which I recommend and so shall not repeat it here.<br />

I would like to emphasise though that the quality of the loam is of the utmost importance. From the loam the<br />

plant will receive many of the necessary elements and so it is important that the loam should be from a good source.<br />

A quantity of soil from your garden is not likely to be of much value. The best loam is the top five or six inch spit<br />

from an old standing meadow which has been stacked grass down for about six months. Loams vary considerably<br />

with regard to their locality. Some growers favour Kettering loam and I experimented with some of this last year<br />

and found that it was excellent, especially for seedlings. The average Cacti grower needs such a small amount<br />

of potting soil each year that I consider that it is money well spent to obtain as good a loam as possible as a basis<br />

for the potting soil.<br />

The time for repotting will depend a great deal on your own particular circumstances. If you have a few plants<br />

or have no greenhouse, then you can leave the repotting until March. If, on the other hand, you have a fairly large<br />

collection you will find that repotting must commence much earlier so as to enable all the plants to be moved<br />

before the late spring. I usually start my repotting in January and carry on as fast as I can through the month.<br />

As long as the potting medium is just moist at the time of potting there is no need to water any plants for perhaps<br />

a month. I find it a good plan to deal with the larger plants first as then the pots can be cleaned ready for other<br />

plants which perhaps require larger pots. Never repot a plant into a pot until the pot has been washed. Whether<br />

you give a plant a larger pot than the one which it has come from will depend not only on the size and health of<br />

the plant, but also on the genus and sometimes species. Some plants never grow very large and so it is unwise<br />

to put such a plant in a large pot. Nothing looks worse in a collection than a plant such as a half-inch diameter<br />

Epithelantha m/'cromer/s in a four-inch pot. Not only will it look odd but it is not as likely to thrive as if it was in<br />

a pot of two inch diameter. On the other hand, a large specimen plant of, say Ech/nocactus grusoni, as large as a

January, 1951 JOURNAL OF GREAT BRITAIN 3<br />

football, will have a considerable amount of root and it is wrong to pack such a plant In a pot only just a trifle larger<br />

than the plant. The amount of root which a large Cactus plant can make cannot be realised until one tries to<br />

move such a plant after it has been planted out in a warm garden for a season. Whilst repotting remember the<br />

tip I have given before and that is, if a plant does not appear to have healthy roots do not repot right away in the<br />

usual potting medium, but re-root the plant first in some verrnicuiite.<br />

The next task will be the sowing of seeds. Each year I get my greatest interest from seed raising, as I have<br />

proved that plants raised from seed in this country grow better and flower earlier than off-sets or imported plants.<br />

The time when they should be sown will depend on when you are able to maintain a temperature of 70 degrees.<br />

If you are unable to do this, then do not sow until April when the natural temperature should be enough to start<br />

the germination of the seeds. Anyone with a little skill can manage to make a small propagating frame, which<br />

can easily keep up a suitable temperature with very little cost. I like to get my seeds sown, either late in January<br />

or early in February, but if I am delayed over late despatch of seeds and am unable to sow until March, I find that<br />

the seedlings are not very far behind by the summer. I have usually so many other things to attend to that I am<br />

glad to get my seeds safely sown in good time. There is no need for me to go over all the details for seed sowing<br />

as my notes of other seasons will give all the necessary detail. If your methods are successful, then do not let<br />

anyone make you change them. If the seeds are fresh and good all that is required for their germination is moisture,<br />

warmth and air. A temperature of about 70 degrees is the best, and don't think that a temperature of 80 will give<br />

you better seedlings, it will probably give weak drawn-up seedlings. Do not cover the small seeds, shade them<br />

from sunshine and do not allow them to dry out. I hear that some people recommend standing the seed pans in<br />

a tray of water. I am afraid I cannot agree with this method. I have never been successful with this method as<br />

I find that the excessive moisture encourages damping off. The pans can be stood in damp, not wet, peat, and I<br />

water overhead with a fine spray and find that, as long as I do not overdo the watering, I get very little trouble<br />

with my seedlings. By the way, the seeds should be plump, and if they are not and appear shrunken, then I am<br />

afraid that the seeds were either not properly fertilised or they were gathered too early. If this is the case, then<br />

the seeds will not germinate at all. Once the seedlings are up you must allow some air in the frame or they will<br />

not thrive. Try to keep them growing all the time ; not too wet, and not too dry.<br />

Among a collection of Cacti, especially Mammillarias, one can occasionally find a plant which has a top-heavy<br />

appearance. The part of the plant near the soil, the neck, is much smaller than the upper part. This may have<br />

been caused by a stunted early growth followed by a period of good and healthy growth. The narrow neck never<br />

seems to swell out to match the upper, fuller growth, and the plant will never make a show specimen without<br />

special treatment. The necessary treatment is given in late April or May when plenty of sun may be expected.<br />

Use a very sharp knife and cut through the plant at the spot where the thickest part of the plant commences.<br />

Leave the lower part in the pot to develop fresh off-sets and place the upper part in the sun to dry the base. This<br />

may take a week, depending on the weather. Do not allow the cutting to get wet through drip. After the base<br />

has calloused over—piace it in some verrnicuiite and keep this just damp. It must not be continually wet or it may<br />

rot. Roots will soon form when the plant can be potted up. !t is amazing how soon the piant develops and the<br />

new growth will be very strong and healthy. This treatment may be used for any plant which does not grow and<br />

which appears to have a shrunken, dried-up neck or stem.<br />

On all bright days the greenhouse should have some windows open, so that plenty of fresh air can get around<br />

the plants. Close the house fairly early each day, before the sun actually leaves the house, if possible, as the warmth<br />

will soon leave by the upper windows as soon as the sun goes down. You must start to water the plants as soon<br />

as they show signs of growth. This is usually apparent at the top growing centre of the plant ; some plants will<br />

start to make new growth earlier than others and so it will not be possible to treat all the plants in the house the<br />

same.<br />

If you introduce any fresh plants into your greenhouse give them a thorough examination first to see that<br />

they have no pests on them. A short time in quarantine will help a great deal as many an otherwise clean and healthy<br />

collection has been infected by afresh plant bearing mealy bug, scale, or red spider. Keep a watchful eye on the<br />

whole collection for pests, as it is so easy to deal with these if there are only a few, but if they are allowed to increase<br />

without check, then the task will be much greater. Always remember too that a healthy growing plant is less likely<br />

to be attacked by pests than an unhealthy one. As the days lengthen you should givs more water to those plants<br />

which are making good growth and, when watering, do see that all the soil in a pot gets moistened. The little<br />

drop necessary to fill up the top of a small pot is net likely to be enough to keep the piant growing well. In<br />

conclusion, may I suggest that fresh labels may be necessary for some plants as you repot them, don't wait until<br />

the old one is unreadable before effecting this change.

THE CACTUS AND SUCCULENT January, 1951<br />

NOTES ON EUPHORBIAS (III)<br />

By J. A. JANSE, F.R.H.S.<br />

(Section Diacanthium)<br />

Euphorbia Royleana Boiss., in D.C., XV, 2, 83 (1862) ; id. in Brandis, Forest Flora of N.W. & C. India, 438 (1874) ;<br />

id. in Hooker, Flora Br. India, V, 255 (1890) ; id. in Berger, Sukk. Euph., 65 (1907) ; E. pentagona Royle, lllustr.<br />

Bot. Himal. Mnt., t 82, fig I, not of Haw (1839).<br />

Original description (translated from the Latin original) ; a shrub, branched ; branches 5-angled, ascending ;<br />

angles acutely prominent, margins undulate with paired spines, more or less subulate, flowers sessile aggregate<br />

or solitary.<br />

This Indian species was first described and illustrated by Royle in his beautiful work on Himalayan plants,<br />

however, the author chose a name already used by Haworth for a South African species, twelve years previously.<br />

Boissier, in his revision of the genus, in De Candolle's Prodromus, therefore, re-named it after Royle. This botanist,<br />

a medical officer in the Indian Army, later Director of the Botanical Garden at Saharanpur, ended his life as Professor<br />

of Botany at Queen's College, London.<br />

Royle's illustration gives a short part of a stem, without leaves and, therefore, apparently made from a specimen<br />

in its resting period. Hooker writes, " leaves not described," and this might have misled Berger to place it in<br />

his sub-section Polygonae between E. canariensis and £. Reinhardtii, two species with which it is only remotely allied.<br />

Its general habit shows much more resemblance with the other Indian species, E. neriifolia L., and E. nivulia Ham.<br />

E. Royleana may be recognised by the 5 to 7-angled, thick stem with the wings sharply prominent. Between them<br />

the sides are rather flat, especially in the older parts of the stem. The large leaves, developed at the tip of the<br />

stem, and soon deciduous, are oblanceolate, at the broadest part 2-| cm. by about 12 cm. in length. In its native<br />

country, the hills of the Suevalak district, it attains a height of 15-16 feet, its circumference being about six feet.<br />

It is difficult to say when E. Royleana has been introduced in our collections ; Berger did not see it in a living<br />

state when compiling his little booklet on Succulent Euphorbias in 1907. I have seen rather large specimens in<br />

the Palmengarten of Frankfurt (Main, Germany), of which one is illustrated in one of the accompanying figures.<br />

Fig. I. E. Royleana Boiss, a young specimen imported from France.<br />

Fig. 2. E. Royleana Boiss, an older specimen in the collection of the Palmengarten, Frankfurt, Germany.<br />

We must apologize to Miss M. Maytham Kidd and to the Botanical Society of South Africa for the wrong<br />

impression and confusion caused by our notice, on page 93, October, 1950. We believed there was only one book<br />

being published, but we now learn there are two. " Wild Flowers of the Cape Peninsula," by Miss M. Maytham<br />

Kidd, by post £3 4s. 2d. and " Wild Flowers of the Cape of Good Hope," issued by the Botanical Society of South<br />

Africa, by post 52/6. These books deal with general flora of South Africa, but contain some succulent material.<br />

Once more we apologize for mentioning the product of one of our advertisers because we feel it is of special<br />

value to the members. We refer to Neale's Photographic Plates. Approximately one hundred plates have already<br />

been issued and their quality and distinctness is extremely good. We need such clear, distinct photographs.<br />

It is not known to many that Curtis' Botanical Magazine commenced, in 1786, as a publication by Curtis and Salisbury,<br />

Seedsmen, of Botanic Nursery, Queen's Elm Turnpike, Brompton, and continues to the present day by the Royal<br />

Horticultural Society and runs into thousands of plates. Neale's Photographic Plates are well on the way to<br />

becoming the Curtis of the cactus and succulent world.<br />

Professor Buxbaum wishes us to draw attention to an unfortunate mistake occurring in the " Euechinocactanae<br />

development " illustration on page 83 of the October, 1950, Journal. In Ramis III Choryphanthanae should, of<br />

course, be Coryphanthanae.

January, 1951 JOURNAL OF GREAT BRITAIN<br />

CARALLUMA MAMMILLARIS, N.E.Br.<br />

By H. HALL<br />

Although this fine " Stapeliad " has been known for a very long time—it was figured as far back as 1783—it<br />

is rarely seen in collections of succulent plants. In the first place, it is not by any means easy to grow, although<br />

I have seen a few vigorous specimens in one English greenhouse where abundant sunshine and clean air were available.<br />

Another factor is the plant's reluctance to root from cuttings though these have been known to do so when they<br />

feel like it ! Furthermore, since it is unlikely to flower, at any rate in England, and if it did, less likely to produce<br />

seeds, the chances of increasing the stock by this speedy means are practically nil.<br />

As I have seen this Caralluma in the wild state in a number of places in S. Africa, a few words about it might<br />

be of interest to readers who like to grow Stapelias. It has a very wide distribution, from the Little Karoo to the<br />

Orange River in the N.W. corner of Cape Province—many hundreds of miles apart—always, however, in very arid<br />

situations. It is not a common plant ; one might not drop across a single specimen in a day's wanderings, and see<br />

perhaps a dozen or so on another occasion. Like most of the Stapelia tribe it is met with in the partial shade of<br />

a shrub or rock as a general rule, nor is this habit confined to this class of succulent. Naturally, such shelter will<br />

offer the best chances for the germination of their seeds but it must not be overlooked that they are wind-borne<br />

seeds in the case of Stapelias and thus readily arrested in their flight by shrubs, etc. As a matter of fact, I have<br />

tracked more than one Stapelia to its lair after observing the drift of the tell-tale " parachutes." Often a plant<br />

will be so completely intergrown with the shrub that supplied the initial shade that the two cannot be separated.<br />

Piaranthus and Duvalia spp are very fond of intermingling with the stems of twiggy shrubs, being extremely difficult<br />

to discern in the sharp shadows cast over them. Frequently the Caralluma has outlived the plant that gave the welcome<br />

shade in its infancy, then taking on the purplish hue so characteristic when in full exposure, a condition it<br />

seems to endure happily. The largest Caralluma mammillaris I have met with in the wild was near Calitzdorp<br />

in the Little Karoo. It stood on a rocky rise, in full sun, with a few branches of a shrub, long since dead, still<br />

existing among the thorny stems of the succulent. It was about two feet tall and about two and a half feet across,<br />

the thorny stems being nearly two inches thick. It would weigh about sixty pounds. To attempt to transport<br />

a specimen of this size would be hopeless for even with the protection of stout gloves (almost a necessity for this<br />

species) the branches would snap off with their own weight when tilted from the vertical, for this tribe is very<br />

brittle and fibreless. The root system is generally central, the bases of the outer branches, though resting on the<br />

ground, rarely have roots of their own. I have seen many examples where branches have been lying on the ground,<br />

perhaps for years, judging by their extreme dessication, but none bore roots, a point which bears out my earlier<br />

remark about reluctance in rooting.<br />

In Namaqualand the species seems to differ in no way from those of the more southerly and eastern Karoo.<br />

The flowers are formed in bunches of about twelve, on extremely short stalks, are nearly two inches across,<br />

the corolla lobes slender and of a rich, velvety, purplish-black colour. They are produced in summer and autumn,<br />

and like many other Stapeliads the fruits appear months after the flowers have withered and fallen, the fruits, of<br />

course, being the usual twin pods characteristic of the entire family. The accompanying photograph depicts a plant<br />

about ten inches tall with several flower clusters, growing in the open at Kirstenbosch. It was collected on the<br />

Ceres Karoo, about 100 miles north of Cape Town, and has endured our somewhat copious rains of the past two<br />

winters surprisingly well. In the wild state it would get about one-tenth of the amount it gets here. Planted in<br />

the crevices of flat rocks on a slight slope in full sun, maximum drainage is obtained. To the right of the plant,<br />

and in front of a second Caralluma, are plants of the silvery leaved Cheiridopsis candidissima, a Namaqualand species<br />

of great beauty.<br />

I have obtained seeds of the thorny Caralluma by gathering branches from wild plants bearing nearly ripe<br />

seed pods which have matured later. In fact, only by such means has it been possible to include this species in the<br />

list of seeds distributed by these Gardens this year, and the reports of good germination, especially from England,<br />

has been our reward for the trouble taken.<br />

The seeds, in common with most of the Stapelia tribe, germinate in a matter of hours, no little encouragement<br />

to those who include this smelly-flowered family in their collections.<br />

If you have not already remitted your subscription for 1951, please do so without delay to the Hon. Treasurer,<br />

Miss D. M. Poore, 48 The Mead, Beckenham, Kent, so that the 1951 programme can be completed. It also helps<br />

our honorary treasurer considerably and saves correspondence and expense.

6 THE CACTUS AND SUCCULENT January, 1951<br />

THE SCIENTIFIC APPROACH TO SUCCULENTS<br />

Champions of fact, fad and fable<br />

By GORDON D. ROWLEY<br />

INSTALMENT ONE<br />

The news of the formation of an International Organisation for Succulent Plant Research—news that will be<br />

welcomed by all seriously interested in the study of succulents—re-opens the old thorny question of the relations<br />

between the scientist and the amateur grower. For years a gulf between them has been apparent, and at worst<br />

this has led to harsh words and isolationism on behalf of just those parties that should be working hand in hand.<br />

The amateurs, forming the vast majority, saw no inducement to attempt to understand the savants, whom they<br />

regarded (often quite justifiably) as incomprehensible and out of touch with any such down-to-earth everyday<br />

topics as plant cultivation. The scientists, for their part, grew cliquish and looked down their learned noses at<br />

anything that had not the official sanction of a University or Research Station. Shall the twain never meet ?<br />

My interest here is two fold. I want, first, to show that both scientist and amateur have something to offer<br />

each other ; that by joining forces their joint effort would be more than merely the sum of the two parts put<br />

together. Then, second, I want to suggest how you,—yes, even the humble grower with a tiny glasshouse—can<br />

make real contributions to the study of succulents if you have but three qualifications ; time, patience, and the<br />

enthusiasm to learn.<br />

First Impressions ; The dark ages<br />

If one looks into the history that lies behind succulent growing in England today, or makes any attempt to<br />

assess how much is reality and how much old wives' tales in current literature, one fact stands out pre-eminently.<br />

It is that the amateur, not the scientist, laid the foundations, ran up the walls, and very nearly tiled the v/hole roof<br />

of our present day knowledge of these most curious plants. In cultivation, at least, practically all our notions go<br />

back to the Smiths and the Joneses who killed a hundred plants in growing three successfully on their sitting-room<br />

window sills or conservatory shelves.<br />

The Scientist<br />

On the other hand, in botanic gardens, universities and research stations no group of plants has been more<br />

neglected, and hence none has lagged farther behind in specialist treatment. The reasons for this, so far as any can<br />

be assigned, are obvious to those with a little experience of growing these plants. They have, to begin with, the<br />

initial and largely false reputation of being difficult to grow. Some, undoubtedly, are. Others are so amenable<br />

to glasshouse treatment that they are every bit as difficult to kill. Then they lack the utilitarian value of the potato,<br />

and the obvious voluptuous gorgeousness of the rose ; theirs is a much more subtle beauty that is often only fully<br />

realised when one has lived with the plant all the year round. Again, because many are so prolific and multiply<br />

so freely, they escape that " rarity complex " that enshrouds the orchids, which are collectors' pieces from the<br />

moment their fungal partner launches the seedling into its perilous and fragile existence. Finally—and this is<br />

perhaps the most potent influence of all in bringing disfavour on succulents—they never know when they are<br />

beaten. Where every other greenhouse plant succumbs to drought, overcrowding, suffocation and starvation,<br />

the Cactus lives on, wrinkling with age and adversity like some embittered hermit to a ghastly skeleton of living<br />

death, expressing in every gnarled deformity the torment of a hostile world. The result ? That collections<br />

everywhere are cluttered up with these veteran warriors, and the public at large sees no reason to change its belief<br />

that Cacti are the freaks of the vegetable world ; nature's little legpull for all the other beautiful things she has<br />

provided. A succulent collection can, after a remarkably short period of neglect, lose its sparkle and freshness ;<br />

if the plants died, no one would be any the wiser, but they do not—they go on, unless a rare benefactor again takes<br />

them in hand, to shout aloud for the rest of their days the struggles of their youth.<br />

So much for the scientist ; our duty to him lies clear. We must build up and publicise collections of such<br />

high quality, authenticity and clean condition that he will be attracted to grow and study them.<br />

The Amateur<br />

Now for the amateur—what of his rights and wrongs ?<br />

I have already handed him a bouquet for so much donkey-work in building up our knowledge of succulents<br />

in cultivation, but how much of that knowledge will stand the test of experiment ?

January, 1951 JOURNAL OF GREAT BRITAIN<br />

When Bradley grew a Selenicereus up the wall of his conservatory and noticed it sending out aerial roots into<br />

the brickwork he concluded, just as anyone else might, that it liked a diet of bricks, and consequently he planted<br />

it and many other succulents in a soil rich in broken bricks. Thus began the mortar rubble craze that continued<br />

for over two and a quarter centuries and, until last year, had never been challenged by strictly controlled and<br />

analysable experiments. The use of tiny pots, a high winter temperature, excessive drainage and many other<br />

popular fads and fancies are handed on year after year as hearsay ; I have traced many of them back to the beginning<br />

of the nineteenth century, and some even earlier.<br />

The need for research<br />

In meeting succulent enthusiasts in various parts of the country I have been very much struck by the lack of<br />

modern experimental work on these plants. The simplest questions fired at one at a meeting so often have to<br />

be answered by saying : " It is generally supposed that . . ." where one v/ould so much like to quote chapter and<br />

verse and say ; "So-and-so PROVED that . . ." Only in a few isolated cases has the necessary research been<br />

carried out, as in the bud formation and metabolic peculiarities of Bryophyllum, the alkaloids of Lophophora, the<br />

flower colour inheritance of Portulaca, and the notable Cactus researches of the Desert Laboratory, California.<br />

Especially is our knowledge deficient where two subjects are jointly involved, as in the relation of plants to insects<br />

or to other plants—think, for instance of the many mysterious fungal and bacterial diseases of Opuntias, or the soft<br />

and dry rots of Stapelias, about which v/e know so little.<br />

A further incentive to research is the great improvement in facilities for cultivating plants under glass : the<br />

design of modern glasshouses to give maximum light and cleanliness ; the use of sterile, standardised compost<br />

mixtures ; the range and potency of new insecticides, and the many efficient types of heating system now at our<br />

disposal. The possibilities of adapting these findings to the special needs of succulents requires immediate, extensive<br />

examination ; they have so far been sampled only by the event garde of enterprising amateurs. The present<br />

wave of enthusiasm for succulents deserves better recognition by the laboratory worker—indeed, it will dwindle<br />

and die prematurely if nothing is done to provide answers for the hosts of problems encountered by the grower.<br />

Will the snow melt to expose our black ignorance back just where we started ?<br />

The Specialist<br />

I have mentioned the term "specialist" once so far, and that term requires some definition here, for<br />

specialists may belong to either of the groups that I have—for want of better names—termed " amateurs " and<br />

" scientists." All modern scientists are specialists—they have to be, for the world of learning is so vast that they<br />

would get nowhere if they attempted to know an equal amount about everything. Of the amateurs turned<br />

specialist, there have been many grand examples. I can quote none better than Adrian Haworth, who entirely<br />

by his own efforts achieved world renown as a writer and authority on all succulents, and was largely responsible<br />

for their return to favour at the start of the nineteenth century. It is surprising how the public rallies when a<br />

strong lead is shown to guide them. Amateur specialists can, on the other hand, be great nuisances when, out of<br />

touch with herbaria and libraries (do you realise just how much has been written on succulents ? I doubt it ! )<br />

they dash around, like frightened burglars, grabbing everything in sight and making a " new species " of it.<br />

A word here, if I may, on the frequent exhortations one reads to turn specialist and purge the collection of<br />

everything but the one chosen group. Hard words are these for people who, like myself, take delight in everything<br />

that comes even within the fringes of the great natural assemblage of succulent plants I But the general idea is<br />

sound and should be the goal of everyone once they get on top of their hobby ; there is more of value and interest<br />

in a collection of twenty plants of one genus than in one of a hundred plants, each of a different genus. The<br />

change-over, however, need not be drastic—there need be no mass slaughter of the innocents overnight. A gradual<br />

infiltration of the selected group, whether they be Coryphanthas or Kleinias, and a little firmness in refusing all but<br />

the best of other sorts, will soon bring about the desired effect. You can always retain the best of your general<br />

collection, and will never be short of eager offers of exchange for the others.<br />

Future Forecast<br />

This opening article is necessarily rather generalised and by way of an introduction. In future articles I should<br />

like to attempt some details of scientific method, the layout of experiments, and suggestions of simple tests that<br />

can give the humblest grower the feeling he is adding a little to our understanding of some of the world's most<br />

advanced and enigmatical plants. Now is as good a time as any to make good the past neglect. The I.O.S.P.R.,<br />

with its imposing programme of research projects, provides one light on a horizon dark with ignorance and<br />

indifference.

8 THE CACTUS AND SUCCULENT January, 1951<br />

EASTBOURNE SUCCULENTS<br />

By E. SHURLY<br />

The middle of October saw us visiting Eastbourne once more where we always admire the really wonderful<br />

show of flowering plants that is Eastbourne's speciality, but our main interest was centred upon the succulents<br />

known to so many who have visited the town.<br />

I have, for years, known of them, but the discussions about air for succulents and pre-occupation with this<br />

number of the Journal made me make enquiries that resulted in meeting Eastbourne's Head Gardener, Mr. A. E.<br />

Clark, who was very co-operative and suggested my seeing Mr. G. Cottington, their nursery manager. So, the<br />

following day, we went to the nurseries at Hampden Park.<br />

Our weekend coincided with the lifting of the succulents from their promenade bed to the nurseries, there<br />

to winter. They plant the succulents out in May or June, according to the weather, leave them out in the open,<br />

with no protection of any kind, until October. They have to stand every kind of weather and all the elements<br />

can centre on them.<br />

I asked Mr. Cottington when they commenced their collection. I was informed that it was so long ago that<br />

nobody present was able to even indicate when, we got to more than thirty years ago, but at that time the collection<br />

was old. Of course, plants have come and gone, visitors and institutions have helped by adding new varieties as it<br />

is their policy not to keep old plants for years. Plants multiply freely and cuttings are taken and the old plants<br />

often thrown away. It is remarkable no publication seems to have taken note of them, certainly they have been<br />

ignored by the cactus Press. It is possible this is mainly due to their not being rare plants, but the virtue is in<br />

their cultivation. We have read of lovely collections in many places which are grown out of doors, usually abroad,<br />

and it is pleasing to sing the praises of those so successfully grown in this country. It will be remembered that I<br />

wrote about Tresco, in the Scillies, in 1946.<br />

The climate of Eastbourne is more salubrious than any in which our plants have to grow, but Eastbourne is<br />

not a perfect Riviera at times—my weekend was cold and wintry. The weather charts for Eastbourne indicate<br />

during 1949 the lowest temperatures for each month, in order of the months, were 30, 25, 30, 33, 36, 44, 50, 49,<br />

51, 33, 32, 31 degrees. Therefore, five of the twelve months were at freezing point or under, and February was<br />

only 25 degrees ! During 1950 the first five months the lowest temperatures were 25, 27, 25, 32, 39—all but one<br />

at freezing or below.<br />

I expressed surprise at the large, free growth of their plants and that I had seen how freely they flower and<br />

offset. Mr. Cottington smiled at my enthusiasm as their efforts were to keep the plants small by throwing away<br />

the over-grown ones, by cutting off roots and in other ways prevent them from becoming unwieldy.<br />

I asked what was their method of cultivation, and was told there was none of special importance. Mr. Cottington<br />

handled nearly a quarter of a million pot plants as well as innumerable seedlings, sown plants, etc. There was<br />

no time for special treatment and, except for an occasional extra sand and lime, the succulents received exactly<br />

the same treatment as everything else. I had witnessed the lifting of the succulents during the weekend and saw<br />

the apparent careless lifting ! We have been warned how carefully we must transplant so as not to injure the<br />

rootlets ! Eastbourne soil is medium loam, inclined to be chalky, but is continually turned over. There is sandstone<br />

under the soil so there is good drainage. When lifted for the winter most are potted up, but taken out of the pots<br />

when planted out in May. Others winter in boxes or ordinary soil, almost just heeled in. Greenhouses are only<br />

heated during the winter, but only just sufficient to keep out frost. The plants become so hardy they can withstand<br />

rough handling and slight injury hardly affects them. Certain of the plants are kept in pots all the time because<br />

of size.<br />

I will now deal with a few of the plants we saw in the promenade gardens and afterwards in the nurseries where<br />

they were examined in the rough after lifting.<br />

Aeoniums : single heads up to 24 inches wide. Every three years they flower, make offsets, which are taken and<br />

the old plants thrown away. There are three kinds ; the largest has a florescence two feet high and thirty<br />

inches wide.<br />

Agave americana : up to four feet in width, always kept in twelve-inch pots. Another Agave, of a smaller type,<br />

six inches in width.<br />

Aloe arborescens : up to two feet high, always in pots, usually simple, offset after one year, offsets taken off and<br />

rooted. When lifted each plant had buds in the form of small cones ; they flower every year. A. Matthioli,

January, 1951 JOURNAL OF GREAT BRITAIN<br />

two feet high, that had been In the open, winter and summer, right through the war and was still perfectly<br />

healthy. It flowered in 1949 for the first time. Other smaller Aloes flowered annually.<br />

Chamaecereus Silvestrii ; make short, compact clumps, each averaging twenty-four heads, from a single small<br />

cutting in eighteen months ; surprising to see the short 2-3-inch heads instead of the long trails we are used to.<br />

Cotyledon orbiculata : as an unnamed Kalanchoe. When kept in the greenhouse it retains its white mealy<br />

appearance, but when planted outside this is lost and it becomes an uninteresting green plant, but makes<br />

plenty of branches.<br />

Crassula lycopodioides : very long and gross, very light in colour. C. Schmidtii grew and flowered freely.<br />

Echeveria : eight different hybrids, growing to eighteen inches wide. Heavy flowering and offsetting. One<br />

retains its red edging in the greenhouse, but loses it outside. Echeveria farinosa is extensively used for carpet<br />

bedding and edging.<br />

Echinops/s multiplex : about two dozen, well grown, healthy and beautifully green, four inches across, offset freely,<br />

flower from May right through the season.<br />

Casteria : one type of star formation, leaves jut out in all directions, large and healthy, free flowering. Another<br />

Gasteria with opposite leaves like Aloe plicatilis, had a history. When Neale's first intended to branch into<br />

cacti and succulents, Mr. Cottington visited them and was given this unnamed Casteria. Still very healthy,<br />

quite eighteen inches across, but had never flowered or offset.<br />

Haworthia : many of the attenuata type, all healthy, but in size no more than we are used to ; free flowering and<br />

offsetting.<br />

Kalanchoe diagremontianum : given by Kew, up to eighteen inches high, flowers freely and gives plantlets every<br />

year.<br />

Kleinia repens : extensively used for carpet bedding and edging. Large plants, broken up for cuttings, boxed<br />

during the winter, free flowering. K. articulata grew to eighteen inches long, branches up to nine inches<br />

long, snails like them ! Broken stems give off pungent smell like menthol. A mealy white Kleinia, much like<br />

Echeveria farinosa, except with narrower leaves, in clumps up to six inches, clumps split up do not flower until<br />

they mature.<br />

Opuntia microdasys : pads not large, but they multiply in close, bunched up sets ; always kept in pots—snails<br />

like them also !<br />

Pachyphytum ; two kinds, larger and thicker than usual.<br />

Mr. Cottington was good enough to send me six plants which I showed to members at the December meeting<br />

and they saw how large they grow and how successfully they have been cultivated in the open. Outdoor cultivation<br />

makes them grosser and many lose colourings that intrigue us, but the full open-air treatment does not prevent<br />

them from flowering and offsetting even more freely than with us, but cacti clump rather than lengthen.<br />

The Eastbourne collection has a lesson for us, and Mr. Clark and Mr. Cottington are to be congratulated.<br />

At the 5th December meeting, Mr. E. Shurly addressed the members on " The Winter care of Cacti." He<br />

first stated that there was little more he could tell them than what Mr. Boarder had written in his many articles,<br />

but he warned members against taking anybody's cultivation advice literally and as final ; members should gather<br />

the principle behind the advice and apply it to their own circumstances ; it was quite impossible for advice to be<br />

given to meet the innumerable conditions under which our plants have to be cultivated. He hoped all members<br />

had taken the preliminary precaution of making their greenhouses and frames weatherproof, as drips, draughts, and<br />

such like were even more fatal to plants than frost. Plants can stand a great deal of cold, but frost is<br />

highly dangerous. On all suitable days ventilation should be given, as air is vital to the well-being of the plants.<br />

While perfectly dry plants rarely are affected by frost, he did not recommend keeping absolutely dry, he believed<br />

in giving them a light watering-can shower occasionally on bright, but not too cold days, as it kept the soil in<br />

condition so that when the warm spring came the plant was able to make progress without checks. Another great<br />

enemy of our plants was the muggy days we have in winter when the air is over saturated with moisture. Heat<br />

is the only remedy. He did not believe in high temperatures during the winter as it prevented the plants getting<br />

their normal dormancy, heat should be only just sufficient to keep out frost.

10 THE CACTUS AND SUCCULENT January, 1951<br />

STEMLESS MESEMBRYANTHEMUMS-cont/nued<br />

By G. G. GREEN<br />

Before describing further species in this wonderful family of succulents, it would be as well, perhaps, to spare<br />

a few words on the wintering problems. I have noticed the various talks, lectures and articles given or to be given,<br />

on the " Wintering of cacti " by various sources, but have failed to find even one given over to succulents. Maybe<br />

the two are to be combined, but the implication is there that these plants present no problems during our cold<br />

months, which goes to prove how easily the collector finds them to understand.<br />

There are, however, one or two points thac should be considered when discussing the Mesembryanthemums,<br />

and I will touch briefly upon them here, leaving the other succulents to those who possess a few back numbers<br />

of this Journal, wherein can be found such necessary details as are required.<br />

If my previous articles have been read, the stemless Mesemfcs. should present no difficulty in winter. The<br />

first requisite, as in the case of Cacti, is a house free from draughts, drips and frost. The first two should rave<br />

been seen to before now, and where no heating system is installed, the plants can be protected during the v/orst<br />

nights by covering with newspaper or brown paper, which should be removed in the morning and dried before<br />

replacing at night.<br />

For those who have planted their Mssembs. into gardens or sunk the pots in gravel, etc., there should be no<br />

fear of the plants freezing over as the soil surface should be dry and the covering of paper at night will be quite<br />

satisfactory.<br />

Indoor plants should be removed from the windows each night and replaced in the mornings. As some species<br />

need some water in the winter, this should be given from the bottom, by standing the pots in water for a little<br />

while, or, in the case of permanently planted species, by the method of the empty pots described before. This<br />

will keep the surfaces dry and prevent damping off of the tender bodies. Should drips from the sash bars appear<br />