Confirmation Bias: A Ubiquitous Phenomenon in Many Guises

Confirmation Bias: A Ubiquitous Phenomenon in Many Guises

Confirmation Bias: A Ubiquitous Phenomenon in Many Guises

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

188 RAYMOND S. NICKERSON<br />

notes. As the participants made their choices,<br />

they were given feedback accord<strong>in</strong>g to a<br />

predeterm<strong>in</strong>ed schedule that was <strong>in</strong>dependent of<br />

the choices they made, but that <strong>in</strong>sured that the<br />

feedback some participants received <strong>in</strong>dicated<br />

that they performed far above average on the<br />

task while that which others received <strong>in</strong>dicated<br />

that they performed far below average.<br />

Follow<strong>in</strong>g completion of Ross et al.'s (1975)<br />

task, researchers <strong>in</strong>formed participants of the<br />

arbitrary nature of the feedback and told them<br />

that their rate of "success" or "failure" was<br />

predeterm<strong>in</strong>ed and <strong>in</strong>dependent of their choices.<br />

When the participants were later asked to rate<br />

their ability to make such judgments, those who<br />

had received much positive feedback on the<br />

experimental task rated themselves higher than<br />

did those who had received negative feedback,<br />

despite be<strong>in</strong>g told that they had been given<br />

arbitrary <strong>in</strong>formation. A follow-up experiment<br />

found similar perseverance for people who<br />

observed others perform<strong>in</strong>g this task (but did not<br />

perform it themselves) and also observed the<br />

debrief<strong>in</strong>g session.<br />

Nisbett and Ross (1980) po<strong>in</strong>ted out how a<br />

confirmation bias could contribute to the perseverance<br />

of unfounded beliefs of the k<strong>in</strong>d<br />

<strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> experiments like this. Receiv<strong>in</strong>g<br />

feedback that supports the assumption that one<br />

is particularly good or particularly poor at a task<br />

may prompt one to search for additional<br />

<strong>in</strong>formation to confirm that assumption. To the<br />

extent that such a search is successful, the belief<br />

that persists may rest not exclusively on the<br />

fraudulent feedback but also on other evidence<br />

that one has been able to f<strong>in</strong>d (selectively) <strong>in</strong><br />

support of it.<br />

It is natural to associate the confirmation bias<br />

with the perseverance of false beliefs, but <strong>in</strong> fact<br />

the operation of the bias may be <strong>in</strong>dependent of<br />

the truth or falsity of the belief <strong>in</strong>volved. Not<br />

only can it contribute to the perseverance of<br />

unfounded beliefs, but it can help make beliefs<br />

for which there is legitimate evidence stronger<br />

than the evidence warrants. Probably few beliefs<br />

of the type that matter to people are totally<br />

unfounded <strong>in</strong> the sense that there is no<br />

legitimate evidence that can be marshalled for<br />

them. On the other hand, the data regard<strong>in</strong>g<br />

confirmation bias, <strong>in</strong> the aggregate, suggest that<br />

many beliefs may be held with a strength or<br />

degree of certa<strong>in</strong>ty that exceeds what the<br />

evidence justifies.<br />

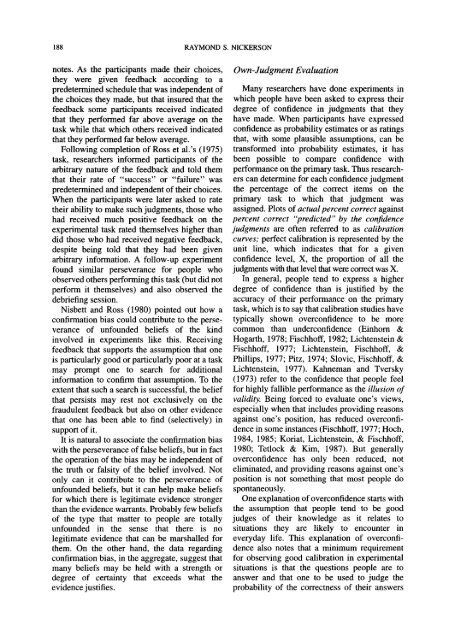

Own-Judgment Evaluation<br />

<strong>Many</strong> researchers have done experiments <strong>in</strong><br />

which people have been asked to express their<br />

degree of confidence <strong>in</strong> judgments that they<br />

have made. When participants have expressed<br />

confidence as probability estimates or as rat<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

that, with some plausible assumptions, can be<br />

transformed <strong>in</strong>to probability estimates, it has<br />

been possible to compare confidence with<br />

performance on the primary task. Thus researchers<br />

can determ<strong>in</strong>e for each confidence judgment<br />

the percentage of the correct items on the<br />

primary task to which that judgment was<br />

assigned. Plots of actual percent correct aga<strong>in</strong>st<br />

percent correct "predicted" by the confidence<br />

judgments are often referred to as calibration<br />

curves; perfect calibration is represented by the<br />

unit l<strong>in</strong>e, which <strong>in</strong>dicates that for a given<br />

confidence level, X, the proportion of all the<br />

judgments with that level that were correct was X.<br />

In general, people tend to express a higher<br />

degree of confidence than is justified by the<br />

accuracy of their performance on the primary<br />

task, which is to say that calibration studies have<br />

typically shown overconfidence to be more<br />

common than underconfidence (E<strong>in</strong>horn &<br />

Hogarth, 1978; Fischhoff, 1982; Lichtenste<strong>in</strong> &<br />

Fischhoff, 1977; Lichtenste<strong>in</strong>, Fischhoff, &<br />

Phillips, 1977; Pitz, 1974; Slovic, Fischhoff, &<br />

Lichtenste<strong>in</strong>, 1977). Kahneman and Tversky<br />

(1973) refer to the confidence that people feel<br />

for highly fallible performance as the illusion of<br />

validity. Be<strong>in</strong>g forced to evaluate one's views,<br />

especially when that <strong>in</strong>cludes provid<strong>in</strong>g reasons<br />

aga<strong>in</strong>st one's position, has reduced overconfidence<br />

<strong>in</strong> some <strong>in</strong>stances (Fischhoff, 1977; Hoch,<br />

1984, 1985; Koriat, Lichtenste<strong>in</strong>, & Fischhoff,<br />

1980; Tetlock & Kim, 1987). But generally<br />

overconfidence has only been reduced, not<br />

elim<strong>in</strong>ated, and provid<strong>in</strong>g reasons aga<strong>in</strong>st one's<br />

position is not someth<strong>in</strong>g that most people do<br />

spontaneously.<br />

One explanation of overconfidence starts with<br />

the assumption that people tend to be good<br />

judges of their knowledge as it relates to<br />

situations they are likely to encounter <strong>in</strong><br />

everyday life. This explanation of overconfidence<br />

also notes that a m<strong>in</strong>imum requirement<br />

for observ<strong>in</strong>g good calibration <strong>in</strong> experimental<br />

situations is that the questions people are to<br />

answer and that one to be used to judge the<br />

probability of the correctness of their answers