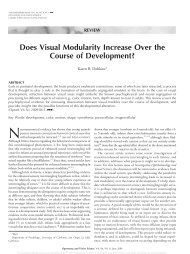

Confirmation Bias: A Ubiquitous Phenomenon in Many Guises

Confirmation Bias: A Ubiquitous Phenomenon in Many Guises

Confirmation Bias: A Ubiquitous Phenomenon in Many Guises

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

176 RAYMOND S. NICKERSON<br />

assumption that people can and do engage <strong>in</strong><br />

case-build<strong>in</strong>g unwitt<strong>in</strong>gly, without <strong>in</strong>tend<strong>in</strong>g to<br />

treat evidence <strong>in</strong> a biased way or even be<strong>in</strong>g<br />

aware of do<strong>in</strong>g so, is fundamental to the<br />

concept.<br />

The question of what constitutes confirmation<br />

of a hypothesis has been a controversial matter<br />

among philosophers and logicians for a long<br />

time (Salmon, 1973). The controversy is exemplified<br />

by Hempel's (1945) famous argument<br />

that the observation of a white shoe is<br />

confirmatory for the hypothesis "All ravens are<br />

black," which can equally well be expressed <strong>in</strong><br />

contrapositive form as "All nonblack th<strong>in</strong>gs are<br />

nonravens." Goodman's (1966) claim that<br />

evidence that someth<strong>in</strong>g is green is equally good<br />

evidence that it is "grue"—grue be<strong>in</strong>g def<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

as green before a specified future date and blue<br />

thereafter—also provides an example. A large<br />

literature has grown up around these and similar<br />

puzzles and paradoxes. Here this controversy is<br />

largely ignored. It is sufficiently clear for the<br />

purposes of this discussion that, as used <strong>in</strong><br />

everyday language, confirmation connotes evidence<br />

that is perceived to support—to <strong>in</strong>crease<br />

the credibility of—a hypothesis.<br />

I also make a dist<strong>in</strong>ction between what might<br />

be called motivated and unmotivated forms of<br />

confirmation bias. People may treat evidence <strong>in</strong><br />

a biased way when they are motivated by the<br />

desire to defend beliefs that they wish to<br />

ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>. (As already noted, this is not to<br />

suggest <strong>in</strong>tentional mistreatment of evidence;<br />

one may be selective <strong>in</strong> seek<strong>in</strong>g or <strong>in</strong>terpret<strong>in</strong>g<br />

evidence that perta<strong>in</strong>s to a belief without be<strong>in</strong>g<br />

deliberately so, or even necessarily be<strong>in</strong>g aware<br />

of the selectivity.) But people also may proceed<br />

<strong>in</strong> a biased fashion even <strong>in</strong> the test<strong>in</strong>g of<br />

hypotheses or claims <strong>in</strong> which they have no<br />

material stake or obvious personal <strong>in</strong>terest. The<br />

former case is easier to understand <strong>in</strong> commonsense<br />

terms than the latter because one can<br />

appreciate the tendency to treat evidence<br />

selectively when a valued belief is at risk. But it<br />

is less apparent why people should be partial <strong>in</strong><br />

their uses of evidence when they are <strong>in</strong>different<br />

to the answer to a question <strong>in</strong> hand. An adequate<br />

account of the confirmation bias must encompass<br />

both cases because the existence of each is<br />

well documented.<br />

There are, of course, <strong>in</strong>stances of one wish<strong>in</strong>g<br />

to disconfirm a particular hypothesis. If, for<br />

example, one believes a hypothesis to be untrue,<br />

one may seek evidence of that fact or give undue<br />

weight to such evidence. But <strong>in</strong> such cases, the<br />

hypothesis <strong>in</strong> question is someone else's belief.<br />

For the <strong>in</strong>dividual who seeks to disconfirm such<br />

a hypothesis, a confirmation bias would be a<br />

bias to confirm the <strong>in</strong>dividual's own belief,<br />

namely that the hypothesis <strong>in</strong> question is false.<br />

A Long-Recognized <strong>Phenomenon</strong><br />

Motivated confirmation bias has long been<br />

believed by philosophers to be an important<br />

determ<strong>in</strong>ant of thought and behavior. Francis<br />

Bacon (1620/1939) had this to say about it, for<br />

example:<br />

The human understand<strong>in</strong>g when it has once adopted an<br />

op<strong>in</strong>ion (either as be<strong>in</strong>g the received op<strong>in</strong>ion or as<br />

be<strong>in</strong>g agreeable to itself) draws all th<strong>in</strong>gs else to<br />

support and agree with it. And though there be a greater<br />

number and weight of <strong>in</strong>stances to be found on the<br />

other side, yet these it either neglects and despises, or<br />

else by some dist<strong>in</strong>ction sets aside and rejects; <strong>in</strong> order<br />

that by this great and pernicious predeterm<strong>in</strong>ation the<br />

authority of its former conclusions may rema<strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>violate.. . . And such is the way of all superstitions,<br />

whether <strong>in</strong> astrology, dreams, omens, div<strong>in</strong>e judgments,<br />

or the like; where<strong>in</strong> men, hav<strong>in</strong>g a delight <strong>in</strong><br />

such vanities, mark the events where they are fulfilled,<br />

but where they fail, although this happened much<br />

oftener, neglect and pass them by. (p. 36)<br />

Bacon noted that philosophy and the sciences<br />

do not escape this tendency.<br />

The idea that people are prone to treat<br />

evidence <strong>in</strong> biased ways if the issue <strong>in</strong> question<br />

matters to them is an old one among psychologists<br />

also:<br />

If we have noth<strong>in</strong>g personally at stake <strong>in</strong> a dispute<br />

between people who are strangers to us, we are<br />

remarkably <strong>in</strong>telligent about weigh<strong>in</strong>g the evidence and<br />

<strong>in</strong> reach<strong>in</strong>g a rational conclusion. We can be conv<strong>in</strong>ced<br />

<strong>in</strong> favor of either of the fight<strong>in</strong>g parties on the basis of<br />

good evidence. But let the fight be our own, or let our<br />

own friends, relatives, fraternity brothers, be parties to<br />

the fight, and we lose our ability to see any other side of<br />

the issue than our own. .. . The more urgent the<br />

impulse, or the closer it comes to the ma<strong>in</strong>tenance of<br />

our own selves, the more difficult it becomes to be<br />

rational and <strong>in</strong>telligent. (Thurstone, 1924, p. 101)<br />

The data that I consider <strong>in</strong> what follows do<br />

not challenge either the notion that people<br />

generally like to avoid personally disquiet<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>in</strong>formation or the belief that the strength of a<br />

bias <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>terpretation of evidence <strong>in</strong>creases<br />

with the degree to which the evidence relates<br />

directly to a dispute <strong>in</strong> which one has a personal