seri$ I I sslsh G".nd - Canterbury Christ Church University

seri$ I I sslsh G".nd - Canterbury Christ Church University

seri$ I I sslsh G".nd - Canterbury Christ Church University

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

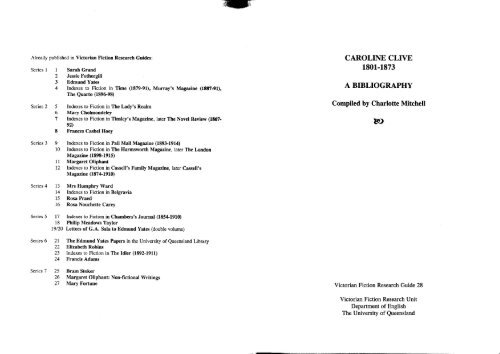

Alrcady published in viclodaD <strong>nd</strong>or Re!€.ftb cuider: CAROLINE CLM<br />

<strong>seri$</strong> I I <strong>sslsh</strong> G".<strong>nd</strong><br />

1E0r_1973<br />

2 Jesie Fotheirill<br />

3 Edmu<strong>nd</strong> Yat€€<br />

4 lld.res to Fictid in rine (lsze-er), Mrr.y,r Mis.,i (rEE74l),<br />

Thc Quarto (1896-98)<br />

seriq 2 5 r<strong>nd</strong>crcs ro Fictid hrhe r,sdy,s R€otm<br />

6 Mart Cholmo<strong>nd</strong>eley<br />

7 Itrd.,t* io Ficrion h lbsleyk Mrgad$, l,r€I The Noycl RGd.r (r$t<br />

92')<br />

E Fr3lB CahdHory<br />

S€rie! 3 9 I<strong>nd</strong>Ex$ io Fiction in Pau MrI Mrggire (1E9U914)<br />

10 ID&rs to FictioD in Tb. Hrlmrworrh Magarin€, latd Tt Llldon<br />

Masdre (1898-r9rt<br />

1l Mrrgarct Onphsd<br />

12 Lrdcrcs to Fictid h Crss€lt fanlly Mr$riDe, lttc. C.!r.ll's<br />

Mryarhc (ff41910)<br />

Series 4 13 Mr6 Humphry Wrrd<br />

14 I<strong>nd</strong>er.q to Fidiotr ir BelgaYia<br />

15 Rola Prr€d<br />

16 RoEa Nouch€{te Crr€y<br />

Series 5 17 I<strong>nd</strong>qes to FictioD in Chmb€.s" JoUInrl O8*r910)<br />

18 Philip Meadors Tryln<br />

19/20 I4tterE of G,A. SrIr to EdDEd Yrtls (double volune)<br />

Series 6 2l TIle f,dmu<strong>nd</strong> Ysaes P.p.n in tte Univcrsity of Quffildd Libnry<br />

22 Elizrb€lh RobiG<br />

23 I<strong>nd</strong>ets io Fiction in The Idl€r (1E92-1911)<br />

24 FYmd. AdMs<br />

A BIBLIOGRAPIfI<br />

Compiled by Charloite Mitchell<br />

Series 7 25 Bram Stoker<br />

26 Margaret Oliphant: Non-fictional Writings<br />

27 Mary Fortune Victorian Fiction Research Guide 28<br />

fA)<br />

Victorian Fiction Research Unit<br />

Department of English<br />

The <strong>University</strong> of Queensla<strong>nd</strong>

Copyright @ Charlotte Mitchell 1999<br />

ISBN 1-86499-t194<br />

ISSN 0158 3921<br />

Published by<br />

Victorian Fiction Research Unit<br />

Department of English<br />

The <strong>University</strong> of Queensla<strong>nd</strong><br />

Australia 4072<br />

VICTORIAN FICTION RESEARCH GUIDES<br />

Victorian Fiction Research Guides are published by the Victorian<br />

Fiction Research Unit within the Department of English, The <strong>University</strong><br />

of Queensla<strong>nd</strong>.<br />

The Unit concentrales on minor or lesser-known writers active during<br />

the period from about 1860 to about 1910, a<strong>nd</strong> on fiction published in<br />

journals during the same period. We would be interested to hear from<br />

anyone working on relevant author-bibliographies or on i<strong>nd</strong>exes to<br />

fiction in journals of ttre period. Any information about the location of<br />

manuscripts, rare or unrecorded editions, a<strong>nd</strong> other material would be<br />

most welcome. Information about gaps or errors in our bibliographies<br />

a<strong>nd</strong> i<strong>nd</strong>exes would also be appreciated.<br />

The subscription for the current (seventh) series of Victorian Fiction<br />

Research Guides is $40 (Ausnalian) for four Guides; single volumes<br />

$A12. Copies of earlier Guides are available at the following prices:<br />

Series 1, 2,3,4,5: $A25 (single volumes $A7); Series 6: $A35 (single<br />

volumes $A10).<br />

Orders should be sent to Dr Barbara Garlick a<strong>nd</strong> editorial<br />

communications to the general editor, Professor Peter Edwards, both at<br />

the Department of English, The <strong>University</strong> of Queensla<strong>nd</strong>, Australia<br />

4O72: fax: 7 -3365-2799; email: b.garlick@mailbox.uq.edu.au.

Caroline Clive in about 1860<br />

Introduction<br />

CONTENTS<br />

Primary Bibliography<br />

Non-fiction<br />

Verse<br />

Fiction<br />

Contributions to periodicals a<strong>nd</strong> anthologies<br />

Translation<br />

Diary<br />

Microfilm edition<br />

Manuscripts<br />

Seco<strong>nd</strong>ary Bibliography<br />

Obituaries<br />

Contemporary Reviews<br />

Other References by Contemporaries<br />

Later Criticism<br />

Thesis<br />

Reference Works<br />

Brief References<br />

lll<br />

29<br />

30<br />

30<br />

32<br />

36<br />

37<br />

38<br />

38<br />

38<br />

4L<br />

4t<br />

4I<br />

45<br />

47<br />

48<br />

48<br />

49

,<br />

a/rt /" 1o--' 7p',//.^ /o-"1 .,<br />

/a./.,i'-ofr /"r "-/J;q<br />

dt^. e" rl<br />

/r4"<br />

/1*/ ,7,<br />

,h lr'.Lnn (o-.c 2<br />

PAUI FBRROI,L<br />

&aIt<br />

BI<br />

'TIII' AUTIIOIT OI'"IX. PODTTS BY<br />

" llot littlc wc know of $hn( nNrcc ir cml ollcr! mi<strong>nd</strong>s,"<br />

lDrtr SfITr(d Ltrriftd.<br />

Jourtt itrElitior,<br />

IYITII A CONCLUDINC IfOTIUII.<br />

'ONDON:<br />

s,ruNDnRS ltND OTtrry, coNl)ul'f sTnI'nT.<br />

&

INTRODUCTION<br />

Mrs Cayhill, in Henry Ha<strong>nd</strong>el Richardson's first novel Maurice Guest (1908),<br />

is an i<strong>nd</strong>olent American who uses fiction as a drug, happy to settle in l-eipzig<br />

because of its "circulating library rich in English novels". Maurice himself<br />

appeases her with tribute of "old Taucbnitz volumes". One of the novels Mrs<br />

Cayhill reads "like a tippler in the company of his bottle" is Caroline Clive's<br />

third novel, Why Paul Ferroll Killed His Wife (1860); she fi<strong>nd</strong>s it, Richardson<br />

says, "dry reading".l No doubt she had the Tauchnitz edition, published in<br />

Leipzig in 1861, one of the little cream paper-covered Collection of British<br />

Authors Series which entertained generations of English-speaking travellers on<br />

the continent of Europe during the railway age.<br />

One would like to know what Richardson expected her readers to<br />

u<strong>nd</strong>ersta<strong>nd</strong> by this reference; whether, for example, she assumed that some of<br />

them would be aware that the novel a<strong>nd</strong> its predecessor, Paul Fenoll (1855),<br />

are, like Maarice Guest itself, studies of a triangular sexual passion, treated<br />

with more detachment a<strong>nd</strong> more emphasis on sexual violence than<br />

contemporary audiences expected from novels by women. Perhaps she simply<br />

took the title because it contrasted nicely with Mrs Cayhill's lazy a<strong>nd</strong><br />

unreflecting personality, so as to emphasize how an appetite for novels may<br />

coexist with an absolute lack of interest in art a<strong>nd</strong> ideas a<strong>nd</strong> an i<strong>nd</strong>ifference to<br />

the human personalities which surrou<strong>nd</strong> one. That Mrs Cayhill is an<br />

u<strong>nd</strong>iscriminating reader is suggested by the heterogeneous list of other novels<br />

she reads:<br />

Shadowed by Three, a most delightful Book. On Friday, Richard<br />

Elsmere, a<strong>nd</strong>-oh yes, I know, it was about a farm, an Australian farm<br />

... a nice book, but a little coarse in parts, a<strong>nd</strong> very foolish at the e<strong>nd</strong>.2<br />

The Story of an African Farm (1883) arfi Roben Elsmere (1888), so<br />

controversial in their day, are reduced to fictional fodder for Mrs Cayhill,<br />

down at the level of. Shadowed by Three (1884), a forgoffen detective story by<br />

Emma M. Murdoch. To those intrigued by the dense u<strong>nd</strong>ergrowth of Victorian<br />

fiction, this picture of Mrs Cayhill i<strong>nd</strong>ulging herself with the Leipzig<br />

circulating library offers tantalizing possibilities. Richardson is interested in<br />

the ironies thrown up by the sordid lives of dedicated artists; no doubt she also<br />

remembers that her own novel may meet an obscure fate like that of those titles<br />

she plays with. In another irony, the unpredictable fashions of twentieth-

2<br />

century literary history have belatedly canonized Richardson in the namo of<br />

"Australian literature" a<strong>nd</strong> *women's writing". They have also brought somo<br />

revival of interest n W Paul Ferroll Killed His Wife a<strong>nd</strong>, in its author, an<br />

interesting personality a<strong>nd</strong> a notable diarist, the disabled wife of a rich<br />

Victorian clergyman, author of meditative verse a<strong>nd</strong> sardonic, intermittently<br />

impressive novels which shocked a<strong>nd</strong> impressed her contemporaries.<br />

$$$$$0$$$$$$<br />

The author of Paul Fenoll was born on 30 June 1801 at Brompton Grove, a<br />

now demolished Georgian terrace in the Brompton Road some hu<strong>nd</strong>red yards<br />

west of the present site of Harrods,3 then a pleasant suburban area. She was the<br />

seco<strong>nd</strong> daughter a<strong>nd</strong> third child of a barrister a<strong>nd</strong>, from 1789 to 1802, Whig<br />

M.P., Edmu<strong>nd</strong> Wigley (1758-1821) a<strong>nd</strong> his wife, Anna Maria Meysey (1770-<br />

1836). Her mother had inherited the ancient Meysey estate of Shakenhurst,<br />

near Cleobury Mortimer, on the Shropshire/Worcestershire border. When<br />

Caroline was about ten Edmu<strong>nd</strong> Wigley changed his surname to Meysey<br />

Wigley; soon afterwards he retired from legal practice a<strong>nd</strong> settled at<br />

Shakenhurst, a country house to which he a<strong>nd</strong> Anna Maria had addcd, in 1798,<br />

soon after their marriage, a red-brick classical facadc in the latest modcrn<br />

fashion.<br />

The Wigleys had five children, Anna, Edmu<strong>nd</strong>, Caroline, Mary r<strong>nd</strong><br />

Meysey, a<strong>nd</strong> seem to have been a happy, prosperous a<strong>nd</strong> united family,'<br />

However, when Caroline was two she contracted a severe illness with a high<br />

fever (perhaps infantile poliomyelitis). She recovered, but both legs worc<br />

partly paralysed, a<strong>nd</strong> she never walked without a stick. Her younger sister,<br />

describing her own childhood in idyllic terms, remembered that the ha<strong>nd</strong>icap<br />

seemed to affect Caroline more as she grew older:<br />

... though her strong mi<strong>nd</strong> & high spirits canied her through childhood<br />

with the same feelings as the rest her privations told as she grew up &<br />

she felt sharply the loss of all the active pleasures in which all her<br />

companions revelled.5<br />

Her consciousness of being crippled was later deeply to affect her writing; it is<br />

also likely that her enthusiasm for literary pursuits was encouraged by her<br />

enforced passivity. A diary of hers which survives for the year 1815 i<strong>nd</strong>icates<br />

that she was learning music, drawing, French, Latin, Greek, history,<br />

geography, mathematics, a<strong>nd</strong> possibly also German; a<strong>nd</strong> the attempts at verse<br />

a<strong>nd</strong> passages of flowery moralizing which she has copied into it speak<br />

eloquently of adolescent intellectual aspiration.6 Scribbled at the front are the<br />

words:<br />

Swift says "that after all her boasted acquirements Woman will generally<br />

speaking be fou<strong>nd</strong> to profess less of what is called learning than a<br />

common school-boy["] Alas! Alas! Alas! Alas! Alas! Alas! Alas! Alas!<br />

Alas!<br />

During Caroline's childhood the Wigley family lived betrveen Lo<strong>nd</strong>on<br />

a<strong>nd</strong> Worcestershire. They had a house in Sackville Street, off Piccadilly, until<br />

about 1813, a<strong>nd</strong> used to spe<strong>nd</strong> some time each year at Shakenhurst, which was<br />

three days'journey from Lo<strong>nd</strong>on. They seem also to have kept a house at<br />

Richmo<strong>nd</strong>, from where one could visit Lo<strong>nd</strong>on a<strong>nd</strong> return within the day, but<br />

to which they used to go a<strong>nd</strong> stay for a week or so. After the move to the<br />

country there were occasional visits to Lo<strong>nd</strong>on or Cheltenham, a<strong>nd</strong> a tour of<br />

Scotla<strong>nd</strong> in 1815. They had a house in Cumberla<strong>nd</strong> Square in Lo<strong>nd</strong>on in 1819.<br />

It was probably at about this time that Caroline developed an attachment,<br />

remembered later with embarrassment, to the novelist Catherine Gore (1799-<br />

1861):<br />

... she was a gay Lo<strong>nd</strong>on y[oun]g lady & very ki<strong>nd</strong> to me in my<br />

chrysalis state ... I used to fall into the most viol[en]t frie<strong>nd</strong>ships & the<br />

one I felt for her was n[ea]rly the str[on]gest of my pass[ion]s. Of<br />

course she did not return it, to an ugly, awkward, half taught,<br />

unintelligible girl like me ...7<br />

In 1821 Edmu<strong>nd</strong> Meysey Wigley died leaving his widow a<strong>nd</strong> three<br />

unmarried daughters of 24, 20 a<strong>nd</strong> 19 living together in genteel comfort.<br />

Edmu<strong>nd</strong>, 23, was already in the army; Meysey, 18, was to be a clergyman.<br />

Anna, the eldest daughter, was attached to a family frie<strong>nd</strong>, John Severne,<br />

whom she married in 1825. Caroline a<strong>nd</strong> Mary, who would inherit some<br />

money, were naturally expected to marry likewise. But Caroline was<br />

ha<strong>nd</strong>icapped by a plain face a<strong>nd</strong> crippled legs a<strong>nd</strong>, besides, had immortal<br />

yearnings. The literary critic Isaac D'Israeli (1766-1848) wrote to her in 1823,<br />

answering an impassioned letter about her aspirations which she had written<br />

u<strong>nd</strong>er a male pseudonym:<br />

I have offered you at your desire such advice as I should give my Son;<br />

but I own I should be uneasy that my son should suffer such a feverish<br />

irritability after... a Poet's name, as you evidently do. Your personal<br />

happiness is too deeply involved in your writing.

4<br />

In 1827 she addressed a similar lener, with samples of her poetry, to the<br />

philosopher Dugald Stewart (1753-1828), whose wife replied in frie<strong>nd</strong>lier<br />

terms. She also published u<strong>nd</strong>er an assumed name, a<strong>nd</strong> no doubt at her own<br />

expense, a volume of theological essays which seems to have been greeted with<br />

absolute i<strong>nd</strong>ifference by an ungrateful public.<br />

In 1829 the Meysey Wigleys were delighted to hear that a distant a<strong>nd</strong><br />

childless cousin on their father's side had died, leaving a large estate, Malvern<br />

Hall, Solihull, near Birmingham, a<strong>nd</strong> a ha<strong>nd</strong>some fortune (more than f8000 a<br />

year) to Caroline's brother Edmu<strong>nd</strong>, who was to change his surname to<br />

Greswolde. Caroline seems to have u<strong>nd</strong>ertaken the office of lady of the houee<br />

for him (he remained in the army a<strong>nd</strong> was often absent with his regimcnt),<br />

while also visiting her mother a<strong>nd</strong> sister.<br />

However, this piece of good forhrne was followed by uncxpcctcd<br />

disasters. First of all her younger brother, the Rev. Mcysey Meysey Wigley,<br />

died as a result of an accident in the house in 1830. Then Edmu<strong>nd</strong>, who seems<br />

to have been close to Caroline, also died young in especially distressing<br />

circumstances. As was not unusual among the English la<strong>nd</strong>ed class, the<br />

Malvern estate was entailed; Edmu<strong>nd</strong> had, that is, a life interest in the estatc<br />

which was held by trustees for the benefit of the family's male heirs. Wishing<br />

to raise a large sum of money to buy himself a colonelcy, he borrowed it<br />

against the security of insurance policies taken out with several different<br />

companies. As he was a young man in apparently good health, with a largc<br />

income a<strong>nd</strong> no depe<strong>nd</strong>ants, there seemed nothing especially imprudent in this<br />

step. Unfortunately, however, Edmu<strong>nd</strong> was one of the victims of the first<br />

European cholera epidemic (he died with his regiment in Irela<strong>nd</strong> in January<br />

1833). The insurance companies refused to pay up, claiming that Edmu<strong>nd</strong> was<br />

an alcoholic a<strong>nd</strong> an epileptic. It is hard to determine the rights a<strong>nd</strong> wrongs of<br />

this issue, which led to a prolonged a<strong>nd</strong> inconclusive legal battle, but Caroline<br />

a<strong>nd</strong> her sisters were convinced of Edmu<strong>nd</strong>'s innocence a<strong>nd</strong> the wickedness of<br />

the insurance companies. She was later to use the experience in her seco<strong>nd</strong><br />

novel, Year after Year (1858).<br />

As a result of Edmu<strong>nd</strong>'s death, Caroline left Malvern, which was<br />

inherited by their uncle Henry Wigley (who changed his name to Greswolde),<br />

a<strong>nd</strong> she moved to Olton Hall nearby, a house of some antiquity which had also<br />

come to the family by inheritance. She spent her time between there a<strong>nd</strong> her<br />

mother's house. The latter's death in 1836 (which had followed Mary's<br />

marriage in 1834) left her living full+ime at Olton. In the division of assets<br />

between the three sisters, Mary a<strong>nd</strong> her husba<strong>nd</strong> Charles Wicksted took the<br />

estate at Shakenhurst a<strong>nd</strong> Anna a<strong>nd</strong> Caroline other property, which amounted<br />

to approximately f75,000 each. Caroline was thus extremely well-off, but<br />

rather lacking in obvious duties a<strong>nd</strong> occupations. She solaced her loneliness<br />

a<strong>nd</strong> filled her leisure partly with literary pursuits, a<strong>nd</strong> partly with an increasing<br />

obsession with her closest frie<strong>nd</strong>, the Rector of Solihull, the Rev. Archer Clive<br />

(1800-1878). Like him she engaged in charitable work in the neighbourhood<br />

a<strong>nd</strong> was interested in the new Poor Law. She also held office as a Surveyor of<br />

Highways. He was frie<strong>nd</strong>ly to Caroline (she was already showing him her<br />

manuscripts before Edmu<strong>nd</strong>'s death) but wanted to marry a much younger a<strong>nd</strong><br />

prettier woman, Georgiana Duff Gordon (c1815-1906), whose mother was<br />

keener on his suit than she herself, a<strong>nd</strong> who finally refused him in February<br />

1839.8 After this experience he seems to have turned increasingly to Caroline.<br />

She discussed with him her reading a<strong>nd</strong> her compositions-for she was still<br />

writing poetry. In May 1840 he brought from Lo<strong>nd</strong>on for her the first copies<br />

of her first volume of verse, N Poems fo V. In the summer of that year they<br />

read the first complimentary reviews a<strong>nd</strong> planned a holiday together in<br />

Germany. Soon after their return in September he proposed marriage to her,<br />

a<strong>nd</strong> they were married at Bayton <strong>Church</strong>, near Shakenhurst, on l0 November.<br />

Thus in a very short space of time she obtained, aged 39, belatedly,<br />

unexpectedly a<strong>nd</strong> to her great delight, a measure of public recognition of her<br />

literary work, the companionship of the man she loved a<strong>nd</strong> the status of a<br />

married woman. This was followed by the birth of a son in January 1842 a<strong>nd</strong> a<br />

daughter in October 1843. Nor did she fi<strong>nd</strong> that these longed-for pleasures<br />

turned to ashes. Her children proved healthy a<strong>nd</strong> beloved; she continued to<br />

idolize her congenial husba<strong>nd</strong>; her small literary success gave her enonnous<br />

satisfaction. In Solihull Rectory, to which she moved after her marriage, she<br />

published two more slim volumes of verse, a story rn Blachuood's a<strong>nd</strong> a satire<br />

on the Oxford Movement. None of these made a gte t noise in the world,<br />

though there were some respectful reviews.<br />

In 1845 their prosperity was further enhanced by the successive deaths<br />

of Archer's elder brother a<strong>nd</strong> his father. From their comfortable rectory in<br />

Warwickshire they moved to Whitfield, near Hereford, a<strong>nd</strong> they became<br />

people of consequence in society. Archer Clive gave up his parish a<strong>nd</strong> lived<br />

the life of a country squire; they had a house in Lo<strong>nd</strong>on as well as a large<br />

country house, a<strong>nd</strong> in both places they entertained more people more often a<strong>nd</strong><br />

more lavishly. Caroline's pronounced taste for literary life was given scope,<br />

a<strong>nd</strong> she cultivated the acquaintance of a number of the celebrities of the day. In<br />

1853 the Clives left Engla<strong>nd</strong> for sixteen months on the Continent while their<br />

house was enlarged, spe<strong>nd</strong>ing the winter in Rome with their two children. The<br />

year after their return Caroline published her first novel, Paul Ferroll, which<br />

made something of a sensation. In 1856 they visited Paris a<strong>nd</strong> she enjoyed a<br />

taste of fame. Her poems were republished, a<strong>nd</strong> a new career seemed about to<br />

open to her as a novelist. In March 1857 she wrote in her diary:<br />

5

6<br />

I thtinlk the past winter has been the happiest time, the culminat[in]g<br />

point of my life. Not that I expect any misfornrnes, but it has been high<br />

Tide-Personally I have enjoyed Life, reading interest[in]g books, &<br />

writing freely-I have given m[ysellf over to Comfort-wheeling about<br />

the house in a chair-not riding; therefore being neither cold tircd nor<br />

afraid.<br />

But advancing age a<strong>nd</strong> successive falls a<strong>nd</strong> strokes inexorably limited<br />

her mobility a<strong>nd</strong> probably prevented her from taking full advantage of the<br />

success of her first novel. Though she published three mote, Year afier Year<br />

(1858), Wy Paul Ferroll Killed his Wik Q860), md John Greswold (1864),<br />

reviewers made it clear (a<strong>nd</strong> a modern reader may well agree) that the promise<br />

of the first was not completely fulfilled. An accident in July 1860 paralysed<br />

her completely at first, a<strong>nd</strong> her legs were almost useless afterwards. In 1865<br />

she had a seizure at the foot of the Alps while on a journey to spe<strong>nd</strong> another<br />

winter in Rome. She recovered the use of one ha<strong>nd</strong>, though her ha<strong>nd</strong>writing<br />

from this point is very shaky, a<strong>nd</strong> her voice was permanently affected. After<br />

this stre never wrote anything more which was published, but she continued to<br />

correspo<strong>nd</strong> with frie<strong>nd</strong>s, a<strong>nd</strong> she supervised the selection of her Poems (1872),<br />

In the late afternoon of 12 July 1873 she was sining in this helpless state<br />

by the fire in the library at Whitfield, surrou<strong>nd</strong>ed by newspapers, when a spark<br />

caught her dress; by the time the footman answered her feeble ring at the bell,<br />

she was enveloped in flame. He beat out the fire with cushions, but she had<br />

been badly burned a<strong>nd</strong> soon sank into a coma, dying at 5 p.m. the following<br />

day.n<br />

$$$$$$$$$$$s<br />

Though she lived more than three score years a<strong>nd</strong> ten, Caroline Clive's career<br />

as a published writer was thus not a long one: she began late a<strong>nd</strong> her career<br />

was cut short. Between 1840 a<strong>nd</strong> 1864 she published with some frequency a<strong>nd</strong><br />

experimented with a considerable variety of literary forms. Rougily speaking,<br />

she began with verse a<strong>nd</strong> moved on to prose, a<strong>nd</strong> on the whole her most<br />

considerable achievements are in prose. Her work in various gerues, however,<br />

does exhibit cornmon features. There are similarities of theme-she is<br />

preoccupied with tension, transience, foreboding, violence a<strong>nd</strong> death-a<strong>nd</strong><br />

there are stylistic similarities-she loves clarity, precision, irony, the morbid<br />

a<strong>nd</strong> the fantastic.<br />

In the spring of 1840 Caroline Meysey Wigley published her first book,<br />

a small thin volume of verse entitled IX Poems. Like most women writers at<br />

this period, she refrained from putting her name on the title page, but signed<br />

the title page "V.", short for "Vigolina', a nickname given her by Archer<br />

Clive. Review copies were sent out, a<strong>nd</strong> she soon received a letter, dated 12<br />

June 1840, from John Gibson Lockhart, the editor of the Quanerly Revi*v,<br />

which afforded her u<strong>nd</strong>ying pleasure:<br />

It is impossible to read the verses of V without being deeply impressed<br />

with his talents, & accomplishments[.] I regret that this No of the<br />

Quarterly Review had been made up before yr little volume reached a<strong>nd</strong><br />

take the liberty, in the view of noticing it next time if possible, of asking<br />

whether you have not published some work of more considerable bulk or<br />

meditate doing so soon[.]to<br />

This was followed by an enthusiastic review in the September issue<br />

which was part of Henry Nelson Coleridge's article on "Modern English<br />

Poetesses", a<strong>nd</strong> which was often referred to by later critics of Clive's work.<br />

He quotes her poem "The Grave", which, probably as a direct result, became<br />

much the best-known of her poems. Terseness a<strong>nd</strong> masculine clarity of thought<br />

were detected by Coleridge a<strong>nd</strong> by subsequent critics, such as Thackeray's<br />

frie<strong>nd</strong> Dr John Brown, an Edinburgh physician a<strong>nd</strong> belleslettrist, whose oncepopular<br />

volume ofessays Horae Subsecivae (1858) includes a rapturous review<br />

of IX Poems which he had first published in 1849. But, in spite of this, neither<br />

a seco<strong>nd</strong> edition, with additions, of IX Poems, nor the longer, melancholy a<strong>nd</strong><br />

reflective narrative poems which followed it-/ Watched the Heavens (L842),<br />

The Valley of the Rea (1851), The Morlas (1853)-achieved as much<br />

recognition as had that first thin little book. She also published two occasional<br />

poems, The Queen's Ball (1847), a grim comedy in octosyllabic couplets based<br />

on a frie<strong>nd</strong>'s story that invitations to a court ball had been sent to 150 dead<br />

people; a<strong>nd</strong> The Glass-berg (1851), a blank verse celebration of the Great<br />

Exhibition in the Crystal Palace.<br />

In l85l Clive recorded in her diary a meeting with the travel writer a<strong>nd</strong><br />

historian Eliot Warburton, who "said such fine things about my poetry that I<br />

was quite astonished. It seemed to me to have so entirely passed out of every<br />

bodys head."rr She made one more attempt to impress the public with a long<br />

poem, also in octosyllabic couplets. In a preface to The Morlns she declared<br />

that she had been working on the poem for many years, a<strong>nd</strong> had had it<br />

corrected by "one of the ablest pencils of the day"(probably that wielded by<br />

Caroline Norton, 1808-1877):<br />

I improved it as far as I was able according to those criticisms, a<strong>nd</strong> now<br />

I feel justified in offering it to the world as the best I can do; which if it<br />

fails to please, fails through want of ability, not for want of pains.<br />

7

8<br />

The narrator of the poem, resting in a clearing in a forest, hears the voice of<br />

the spirit of the valley, speaking of the change of history, the progress of man<br />

towards enlightenment, the inevitability of the natural cycle of lovc a<strong>nd</strong> death,<br />

all of which appear mysterious until <strong>Christ</strong>ianity gives them meaning. The<br />

paradox of the existence of suffering a<strong>nd</strong> multifarious humanity in the midst of<br />

a calm a<strong>nd</strong> inexorable universe is the contrast which interests her. The spirit<br />

remarks to the narrator:<br />

I love thy melancholy eye,<br />

The portal of a musing mi<strong>nd</strong>,<br />

The lip where the long stifled sigh<br />

Tums to a smile for human ki<strong>nd</strong>.<br />

The poem was no more popular than its predecessors, a<strong>nd</strong> this may have<br />

influenced Clive's decision to embody her quizzical view of life in fictional<br />

form. She had hitherto published in prose only a macabre story in Blacl

l0<br />

gentry. He discourages the attachment between his daughter Janet a<strong>nd</strong> one of<br />

their neighbours, a<strong>nd</strong> refuses a seat in parliament after hearing that Franks's<br />

widow has recovered from an illness. When Mrs Franks is arrested he<br />

confesses that he had himself killed his first wife. His seco<strong>nd</strong> wife dies of<br />

shock. Janet with her lover's help bribes the prison governor a<strong>nd</strong> escapes<br />

abroad with her father. The novel e<strong>nd</strong>s with him asking if she can still love<br />

him. She says yes. A Concluding Notice, in effect an additional chapter, was<br />

added to the third a<strong>nd</strong> subsequent editions of the book. It shows the death in<br />

America of Ferroll, who has escaped from prison.<br />

The Concluding Notice was no doubt added in response to the anxiety<br />

a<strong>nd</strong> perplexity the book created in its first readers. The principal reasons for<br />

this were two: Ferroll escapes punishment, a<strong>nd</strong> the way the story is revealed<br />

leaves it extremely unclear what the reader is supposed to think about his<br />

character. Is he a villain? Or is he a hero? Is he (most unsettling of all) both at<br />

once? What does the novelist mean by having this plot a<strong>nd</strong> telling it in this<br />

way? None of these questions can be answered straightforwardly.<br />

The epigraph to the novel is: "How little we know of what passes in<br />

each other's mi<strong>nd</strong>s." The gradual revelation of Ferroll's guilt is contrived<br />

through i<strong>nd</strong>irect hints. At moments Clive seems to be suggesting that her<br />

technique is purely dramatic, in a way which recalls the experiments of<br />

Dickens a<strong>nd</strong> Wilkie Collins:<br />

If he had been in the habit of talking over his secrets to himself, it is<br />

probable he might have said something very much to the purpose of this<br />

story. However, he was not, so what he thought remains unrevealed;<br />

what he did say, casts no light on the past or the future. (118)<br />

The reader is only to know what is revealed by utterance, by action. This is, of<br />

course, disingenuous; we have already gathered more than we have been told.<br />

But even the approach to such a technique challenged the reading-habits of her<br />

mid-Victorian audience. The central innovation is the presentation of the hero.<br />

We are invited to fi<strong>nd</strong> him selfish, autocratic a<strong>nd</strong> obsessive, but also admirable<br />

a<strong>nd</strong> exceptional. Clive plays with the reader's expectations throughout. Early<br />

on, his i<strong>nd</strong>ifference to his first wife, his failure to visit her corpse or pray<br />

beside her coffin, are ambiguously placed so that the reader is uncertain<br />

whether the function of the incidents is to i<strong>nd</strong>ict Ferroll or to mock the<br />

simplicity a<strong>nd</strong> conventionality of the onlookers:<br />

A man more anxious about appearance would probably have constrained<br />

himself to visit the room where the body of his wife lay; but Mr. Ferroll<br />

was perfectly i<strong>nd</strong>ifferent in this, a<strong>nd</strong> all other instances, as to what was<br />

said of him. (15)<br />

In fact the comment has both effects: it is an early example of the way his<br />

crime is made to elevate him above as well as set him apart from other men.<br />

Thus the authorial detachment conceals a real ambiguity of attinrde throughout.<br />

Even after his crime is apparent Ferroll continues to assert his intelligence a<strong>nd</strong><br />

humour at the expense of his neighbours, a<strong>nd</strong> the novelist, regardless of<br />

literary morality, never satisfies her readers with a thoroughgoing expression<br />

of remorse from her hero's lips.<br />

Clive replied to her critics after the book came out in the Concluding<br />

Notice, in the Prefix to her next novel, Year after Year, a<strong>nd</strong> in the 1860<br />

"prequel" Wlry Paul Fenoll Killed His Wife.ln the first she killed him off; in<br />

the seco<strong>nd</strong> she described him as "a man in whom conscience is superseded by<br />

intellect"; a<strong>nd</strong> in the third she elaborated on his sufferings at the ha<strong>nd</strong>s of his<br />

first wife. She also recorded in her diary a conversation with the novelist<br />

Prosper M6rim6e in which she denied that Ferroll was amiable.l6 None of<br />

these statements amounts to a recantation, a<strong>nd</strong> it is difficult to see how she<br />

could have resolved the difficulties of her early readers without extensive<br />

rewriting. In the late twentieth century the shock of discovering that a man of<br />

high intellect a<strong>nd</strong> good social sta<strong>nd</strong>ing is a murderer is no doubt less keenly<br />

felt, but in 1855 Ferroll's mixture of good a<strong>nd</strong> bad qualities, a<strong>nd</strong> the fact ttrat<br />

his crime is revealed only by his own scrupulous confession, subverted<br />

fu<strong>nd</strong>amental beliefs in the consistency of character a<strong>nd</strong> in the effectiveness of<br />

social controls.<br />

Reviews of Paul Ferroll gave almost unanimous praise to the writing,<br />

even though the story was often fou<strong>nd</strong> immoral a<strong>nd</strong>/or unlikely. The reviewer<br />

in the National Review (perhaps R. H. Hutton) respo<strong>nd</strong>ed to Clive's<br />

characteristic irony:<br />

There is a peculiar mixture of emphatic simplicity a<strong>nd</strong> yet rhetorical art<br />

in the style; so that a thought or sentence which begins in the<br />

commonplace is heightened into point a<strong>nd</strong> pungency by a single<br />

unexpected finishing-stroke as it concludes. t7<br />

The structural irony is u<strong>nd</strong>erlined by the tone of the narrative voice, in a way<br />

that, as Hutton implies, becomes one of the chief pleasures for the reader.<br />

Black comedy is not infrequent; Ferroll often makes jokes at tense moments,<br />

as when a chatty neighbour observes that no-one will mention Mrs Franks to<br />

Mrs Ferroll, "Certainly it is not a subject upon which any judicious person<br />

would wish to entertain her" Q29).<br />

Another noteworthy feature of the book is its treatment of Ferroll's<br />

ll

12<br />

obsession with his seco<strong>nd</strong> wife. When she is absent he displacos his sexual<br />

frustration by riding furiously on a horse a<strong>nd</strong> swimming u<strong>nd</strong>cr a waterfall.<br />

When she is present he monopolizes her, is jealous of their child, doma<strong>nd</strong>s her<br />

attention regardless of her health. It is all very unusual as a portrayal of<br />

reciprocated married love at this period. The author refrains from offering her<br />

opinion as to how far the Ferrolls' mutual passion is ideal, how far excessive,<br />

morbid a<strong>nd</strong> distorted. On ttrat subject as on others, one has to make up one's<br />

own mi<strong>nd</strong>.<br />

Ferroll himself is a writer, a contributor to reviews a<strong>nd</strong> an occasional<br />

poet. This is curious, because Clive's own first book, the long-forgotten<br />

venture into theology, had been published u<strong>nd</strong>er the name Ferrol. One begins<br />

to suspect an element of identification, especially when she attributes her own<br />

verses to him a<strong>nd</strong> treats his literary eminence with a deference amounting to<br />

intellectual snobbery, which is striking in a book so concerned to mock<br />

pretension of all ki<strong>nd</strong>s:<br />

He had written a few things which gave him fame, a<strong>nd</strong> from time to<br />

, time there issued from the Tower a brilliant article, a few exquisite<br />

verses, or a fine fiction, which kept the attention of the reading public<br />

upon him. (28)<br />

The extent to which the hero is a projection of the author's fantasies of literary<br />

success is perhaps the final enigma in a very enigmatic text.<br />

Year after Year (1858), Clive's next novel, though it made less noise<br />

than its predecessor, also bears her personal stamp. It is based on a single<br />

character a<strong>nd</strong> a single idea: it is concise, harsh, ironical, intelligent, a<strong>nd</strong> relates<br />

interestingly to some developments in the contemporary novel.<br />

The story is recounted by Katherine Buckwell, the plain a<strong>nd</strong> illegitimate<br />

daughter of a rich baronet. She is brought up with her legitimate brother Gray,<br />

whom she adores a<strong>nd</strong> who is the only person who values her. Orphaned, they<br />

set up house together, a<strong>nd</strong> for a year live quietly a<strong>nd</strong> happily, saving money to<br />

pay off debts Gray has contracted as a child. But a frie<strong>nd</strong> tempts Gray to join<br />

in county society, a<strong>nd</strong> Katherine becomes gradually isolated. Then he is<br />

accidentally killed, a<strong>nd</strong> the insurance companies from whom he has raised<br />

money make difficulties, claiming he has acted dishonestly. The rest of the<br />

novel is taken up with the legal processes, as Katherine risks destitution to<br />

fight for her brother's honour. It e<strong>nd</strong>s as she wins.<br />

It is a novel about the i<strong>nd</strong>ividual a<strong>nd</strong> society, the pressures of the<br />

community, the needs of the affections a<strong>nd</strong> family love a<strong>nd</strong> loyalty. Katherine<br />

is an interesting character; her tone is dry a<strong>nd</strong> plangent, her anitude plausibly<br />

shaped by her co<strong>nd</strong>ition, "a disgraceful situation, a<strong>nd</strong> an unamiable exterior"<br />

(4). Of her brother she says:<br />

He was of honourable station, beautiful, a<strong>nd</strong> rich; a<strong>nd</strong> his feelings<br />

towards the world were the very opposite to those which I acquired.<br />

Confident of welcome, accustomed to ornament society, a<strong>nd</strong> to be<br />

wished for when he was to come, missed when he stayed away, he took<br />

frankly to the world ... (4)<br />

Katherine is a spectator, conscious of the doubleness of life: "the things<br />

spoken in a corner, a<strong>nd</strong> those which are said aloud in company, may differ<br />

very much from one another" (2). Her role is to expose to the reader the ugly<br />

reality. The figure of Dr Monkton, disillusioned by an unhappy past, sta<strong>nd</strong>s<br />

for those who have aba<strong>nd</strong>oned optimism. He recomme<strong>nd</strong>s resignation to<br />

Katherine:<br />

It was very evident that philosophy was made on purpose for me. I was<br />

ugly, a<strong>nd</strong> philosophy says beauty is of no sort of consequence; I held to<br />

happiness by only one tie, a<strong>nd</strong> that was my connexion with Gray, which<br />

the natural progress of life a<strong>nd</strong> its events threatened almost visibly to<br />

weaken. Philosophy said that self-depe<strong>nd</strong>ence was the finest state of<br />

mental existence, a<strong>nd</strong> that solitude had charms of the first order for<br />

those who knew how to enjoy it. To impart philosophy to me, therefore,<br />

was a favourite aim of Dr. Monkton; a<strong>nd</strong> I was a very docile pupilonly<br />

in my heart I never either u<strong>nd</strong>erstood nor allowed that it would not<br />

be better to be rich, admirable, a<strong>nd</strong> happy, than to be poor, plain, a<strong>nd</strong><br />

philosophical. (64)<br />

Her voice mingles irony a<strong>nd</strong> i<strong>nd</strong>ignation. Another aspect of this theme is<br />

touched on in the figure of Jonathan Wolfe, a lone autodidact befrie<strong>nd</strong>ed by the<br />

Buckwells, who weeps over Alison's Essays on Taste because he has no-one to<br />

discuss it with: "He said he never heard any comment, except 'That's all very<br />

good, a<strong>nd</strong> all very right, a<strong>nd</strong> all very true ...'' (37). While she has Gray,<br />

Katherine has a companion to sympathise with "the crude strange fancies<br />

which haunt everybody's youth" (30); losing him, she is cut off from<br />

everything familiar. His uncle inherits a<strong>nd</strong> she sees:<br />

... how a hu<strong>nd</strong>red objects were become superfluous in the house, which<br />

used to belong to its most intimate habits. All those which had got their<br />

place through the custom ofa life spent there, a<strong>nd</strong> which were necessary<br />

to our old ways of passing time, or which were the marks of how it had<br />

been passed, were now fit only to be cast away by a new possessor.<br />

13

l4<br />

(183)<br />

Such is the tone of the novel: morbid, tense, self-conscious a<strong>nd</strong> acute.<br />

Katherine reproves the heartlessness of Dr Monkton, but her own emotions<br />

fi<strong>nd</strong> no satisfactory outlet, a<strong>nd</strong> she e<strong>nd</strong>s in much the same case as Jonathan<br />

Wolfe was fou<strong>nd</strong> in: cut off from the commerce of the intellect or the<br />

affections. In her role as narrator she is given the novelist's authority to<br />

interpret a<strong>nd</strong> u<strong>nd</strong>ersta<strong>nd</strong> the other characters. In this capacity she contrasts<br />

with Gray, whose straightforwardness permits him to be deceived by the<br />

fashionable beauty Mrs Carey-he takes people at face value. There is a<br />

persistent theme about the interpretation of the feelings of others. A relation,<br />

Mr Tapeworm, is a caricature of precision, who remi<strong>nd</strong>s us of the difficulty of<br />

sympathy: "I see, by fictitiously representing myself to be the inner man of<br />

your consciousness ... the state ofyour ratiocination on the subject ..." (140).<br />

On another occasion he says of the insurance men: *Do you know their<br />

interest is so great in disbelieving the truth, a<strong>nd</strong> believing the untruth, that<br />

obliquity of vision is not unlikely to be generated by fiction of self-concern<br />

[?]" (204-0s).<br />

As the word "fiction" remi<strong>nd</strong>s the reader, the task of the novelist is to<br />

put the reader into sympathy with the mi<strong>nd</strong>s of others, to enlarge his solipsistic<br />

vision. PauI Ferroll had been attacked for doing so too thorougtrly, for<br />

aba<strong>nd</strong>oning the moral spectacles which correct vision. In that novel the<br />

unexpectedness of the story's being told from the murderer's point of view<br />

achieves an effect of freshness, of a narrative slightly askew. Year afier Year,<br />

very much an autobiography about ways of interpreting the world, continually<br />

remi<strong>nd</strong>s us that the heroine's personality gives her a special obliquity of vision.<br />

In fact there is mutual u<strong>nd</strong>ersta<strong>nd</strong>ing between none of the characters, a<strong>nd</strong> only<br />

in a few cases mutual affection. The extent to which even Katherine's feelings<br />

are governed by her own interests is expressed when during the legal process<br />

she has to go a<strong>nd</strong> see Dr Monkton: "I ... remembered, with great pleasure,<br />

that my old frie<strong>nd</strong> was at this time suffering from one of his frequent attacks of<br />

lumbago, which I was quite certain would secure me in fi<strong>nd</strong>ing him at home"<br />

(275-6). Another scene with a similar a<strong>nd</strong> characteristic irony occurs at the<br />

height of the insurance trial, at a moment of great tension:<br />

The door of the court opened again, a<strong>nd</strong> nvo dusky figures issued<br />

together, whom we presently recognised to be the two principal<br />

champions, a<strong>nd</strong> of whom, Mr Son's burning face a<strong>nd</strong> moist brow bore<br />

witness that he had but that moment ceased from energetic exertion. Sir<br />

John Interest a<strong>nd</strong> he walked slowly rou<strong>nd</strong> the hall, in order, probably,<br />

that they might grow cool before going into the outer air; a<strong>nd</strong> it seemed<br />

v<br />

i<br />

I<br />

as though they had taken the moment to confer on some point in which<br />

they both were greatly concerned.<br />

... They were so intent upon their own conversation that they did not<br />

observe us; a<strong>nd</strong> as they passed, Mr. Son said-<br />

"There's no doubt Jenkins will be acquitted if you can prepossess the<br />

jury that train oil is of the nature of spermaceti." (362-3)<br />

The gra<strong>nd</strong> illusion of the legal process, its acting, its arcana, contrasts<br />

with the burning emotion of Katherine's feelings about the outcome, but<br />

matches the preoccupation throughout the book with the way objective reality'<br />

is patterned by the subjective view of the i<strong>nd</strong>ividual. Like the debris of<br />

Katherine's daily life at the house she must leave, the material of her law case<br />

is, for other people, devoid of significance. In the examples I have quoted a<strong>nd</strong><br />

throughout the novel there is an effective tension between the passion of her<br />

feeling a<strong>nd</strong> the coldness of her description, a<strong>nd</strong> between the importance of her<br />

identity a<strong>nd</strong> experience to herself, a<strong>nd</strong> the i<strong>nd</strong>ifference of those about her.<br />

Llke Paul Ferroll, Year afier Year is full of waiting a<strong>nd</strong> of anticipation:<br />

a<strong>nd</strong> again there is a marked absence of interpretive conclusion, a refusal to<br />

u<strong>nd</strong>ertake the part of fate dispensing justice, to an extent which might be held<br />

to i<strong>nd</strong>icate a lack of faith in such patterns. Clive terminates both books without<br />

asserting the authority of the narrative voice. Her concern seems to be<br />

principally with the i<strong>nd</strong>ividual u<strong>nd</strong>er the pressure of neurotic states of mi<strong>nd</strong>. At<br />

the e<strong>nd</strong> of both books the outsider has no prospect of readmission into society,<br />

for Ferroll is a murderer a<strong>nd</strong> Katherine's brother is dead. The reader is<br />

deserted at what is only a moment of stasis, a<strong>nd</strong> the author does not<br />

acknowledge a duty to resolve these difficulties: conveying the uncertainty of<br />

the operations of the universe appears to be part of her project. Characters a<strong>nd</strong><br />

reader remain in the ha<strong>nd</strong>s of an ordering principle as unknown as it is<br />

perverse.<br />

Great emphasis is laid on the necessity for love, conversation, comfort,<br />

family a<strong>nd</strong> frie<strong>nd</strong>s. The time which Katherine a<strong>nd</strong> Gray spe<strong>nd</strong> alone together<br />

peacefully a<strong>nd</strong> charitably is referred to as "my own Eden", a<strong>nd</strong> their gradual<br />

involvement with the outside world is the beginning of her troubles, just as<br />

Ferroll's domestic haven is threatened by the encroaching world. However<br />

Clive proposes no source of comfort other than family love: <strong>Christ</strong>ian<br />

asceticism is explicitly rejected both as Monkton's cold philosophy a<strong>nd</strong> as<br />

Wolfe's self-flagellating fanaticism. God is absent; a<strong>nd</strong> all that remains is the<br />

i<strong>nd</strong>ividual, with a subjective view derived from personal experience, operating<br />

ignorantly within the networks of society, upheld only by a stoic pride.<br />

The form in which Year afrer Year is cast was a popular one in the<br />

1850s: the plain woman's autobiography. The huge success of. Jane Eyre<br />

15

l6<br />

(1847) set a fashion for first-person narratives, a<strong>nd</strong> stories of clever,<br />

i<strong>nd</strong>epe<strong>nd</strong>ent women. The 1840s had seen a move towards the novel of middleclass<br />

domesticity, usually patterned as a love-story, a<strong>nd</strong> there was a fashion for<br />

naming novels after their heroines, which i<strong>nd</strong>icates a bias in favour of the stuff<br />

of female lives: examples are Lady Georgiana Fullerton's Ellen Middleton: A<br />

Tale (1844), Elizabeth Sewell's Margaret Percival (1847), Anne Marsh's<br />

Emilia lfi<strong>nd</strong>ham (1846), a<strong>nd</strong> Catherine Sinclair's Jane Bouverte, or,<br />

Prosperity a<strong>nd</strong> Adversity (1846). Such a title also is Jane Eyre: An<br />

Autobiography, i<strong>nd</strong>icating that it proposes to deal with a woman's life from a<br />

woman's point of view, a<strong>nd</strong>, in the deliberate unpretentiousness a<strong>nd</strong><br />

unglamorousness of the name, making a statement about the novel's realism.<br />

Publishers notoriously influence the selection of titles in response to the<br />

dema<strong>nd</strong>s of the market, a<strong>nd</strong> the flood of titles of this ki<strong>nd</strong> after 1847<br />

u<strong>nd</strong>oubtedly reflects the Jane Eyre phenomenon. Not unheard of before<br />

(Amelia Opie, Adeline Mowbray, 1804; Disraeli, Henrietta Temple: A Inve<br />

Story, 1837), it was used for the first time by many novelists after 1847. Julia<br />

Kavanagh published Daisy Burns (1853); Geraldine Jewsbury, Marian Withers<br />

(1851). Even the hack G.W.M. Reynolds turned fromThe Parricide , or, The<br />

Youth's Career of Crime (1847) to Mary Prtce, or, The Memoirs of a Servant-<br />

Maid (1852), a<strong>nd</strong> the veteran historical novelist G.P.R. James was reduced to<br />

writing a love story about Poor Law reform called Margaret Graham: A Tale<br />

Fou<strong>nd</strong>ed on Fact (1848). Elizabeth Gaskell called her first novel Mary Barton:<br />

A Tale of Manchester Life (1848), a<strong>nd</strong> Margaret Oliphant called hers Passages<br />

in the Ltfe of Mrs. Margaret Maitla<strong>nd</strong>, of Sunnyside, Written by Herself<br />

(1849). Other novelists announced in title or subtitle that their novel was<br />

prosaic, domestic, autobiographical, or concerned with the outsider; examples<br />

include Dinah Craik, Bread upon the Waters: A Governess's Life (1852), Mary<br />

Martha Sherwood, Caroline Mordaant, or, The Governess, Harriet Parr<br />

("Holme Lee'), Kathie Bra<strong>nd</strong>e: A Fireside History of a Quiet Life (1856).<br />

Not all these novels, of course, live up to the expectations raised by<br />

their titles, but the fashion reflects a desire to depict the lives of "ordinary"<br />

middle-class women which was inspired by Charlotte Brontd. This raised<br />

groans from some contemporary critics. The Westmiruter Review declared in<br />

1854 that "these self-involved a<strong>nd</strong> self-reliant young ladies, misu<strong>nd</strong>erstood, as<br />

a matter of course, by their nearest ki<strong>nd</strong>red, a<strong>nd</strong> all apparently 'done after'<br />

'Jane Eyre' ... have been much the fashion of late".lE The Examiner observed<br />

plaintively in 1856:<br />

Here are four of the last story-books that have reached us. They are all<br />

written in one form- ... autobiographies by women .... Perhaps this<br />

may not be an unsuitable oppornrnity of calling the attention of all<br />

persons who are at this moment, or may be hereafter, engaged on<br />

projecting novels, to the fact that the form, a<strong>nd</strong> much of the subject too,<br />

of that ki<strong>nd</strong> of sentimental autobiography whereof a lady is the heroine,<br />

is by this time very nearly as familiar to the public as it can be made.le<br />

Walter Bagehot complained in 1858 of the fraud perpetrated on the<br />

unsuspecting purchaser of a novel who discovers that "he has only to peruse a<br />

narrative of the co<strong>nd</strong>uct a<strong>nd</strong> sentiments of an ugly lady'.2o One of the<br />

reviewers of The MilI on the Floss in 1860 praised Maggie Tulliver for being<br />

"far, far removed from the 'faultless monster' of the old romance, a<strong>nd</strong> still as<br />

far from the pale, clever, a<strong>nd</strong> sharp-spoken young women whom Jane Eyre<br />

made fashionable for a time".21<br />

Margaret Oliphant, discussing the phenomenon of the influence of Jane<br />

Eyre less sarcastically a<strong>nd</strong> a<strong>nd</strong> at greater length in Blachuood's in 1855,<br />

realized the feminist implications of the new heroine, who does not want<br />

deference but fights with men on tenns of emotional equality.22 This novel of<br />

anti-romance a<strong>nd</strong> anti-chivalry was a crucial stage in the serious treaEnent of<br />

women in fiction. Though the heroine of Year afier Year is not a governess<br />

a<strong>nd</strong> does not have a love-affair, her sense of being an outsider, her<br />

autobiographical self-analysis, a<strong>nd</strong> her passionate desire for involvement in<br />

society, identify her strongly with this fashion of the 1850s; the novel thus<br />

belongs firmly in its period, though its author wrote it out of memories more<br />

than nrenty years old, an example of the evolving novel of the woman of<br />

character.<br />

Late in 1860 Clive published Why Paul Feroll Killed His Wife, which<br />

purports to show the events which preceded those n Paul Fenoll: the<br />

machinations whereby his first wife estranged him from his seco<strong>nd</strong>, an episode<br />

which has only been mentioned in the earlier book. Elinor Ladylift, pretty a<strong>nd</strong><br />

poor a<strong>nd</strong> brought up in a man-hating convent, is sent to live with her elderly<br />

guardian a<strong>nd</strong> his young, rich half-sister Laura. Laura loves Leslie (not his real<br />

name, we are told), who is arrogant a<strong>nd</strong> possessed of great ability, but has<br />

been brought up without parents a<strong>nd</strong> therefore lacks humanity. Leslie teaches<br />

Elinor to admire waterfalls, a<strong>nd</strong> gradually she learns something of the world's<br />

corruptions. He aba<strong>nd</strong>ons his original intention of simply making her love<br />

him, a<strong>nd</strong> offers her marriage. Laura, however, succeeds in making him think<br />

Elinor deceitful, a<strong>nd</strong>, after nursing him through brain fever, marries him<br />

herself. The marriage proves unhappy, her lies are revealed, a<strong>nd</strong> kslie fi<strong>nd</strong>s<br />

Elinor in the convent, where he is permitted one interview. The novel e<strong>nd</strong>s in<br />

deadlock:<br />

Violent were the passions of the strong but fettered man, fierce the<br />

17

l8<br />

hatred of the powerful but baffled intellect; wild was the fury of the<br />

man, who believed in but one world of good, a<strong>nd</strong> saw the mortal<br />

moments passing away, unenjoyed, a<strong>nd</strong> irretrievable.<br />

Out of those hours arose a purpose. The reader sees the man, a<strong>nd</strong><br />

knows the deed. From the premises laid before him, he need not i<strong>nd</strong>eed<br />

have concluded that even that man would do that deed; but since it was<br />

told, in 1855, that the husba<strong>nd</strong> killed the wife, so now, in 1860, it is<br />

explained why he killed her. (333)<br />

It is not so much a justification as an explanation, a<strong>nd</strong> has no surprises to offer<br />

the reader of the earlier novel. The hint of atheism which we are given here<br />

("believed in but one world of good") is not a persistent theme: Ferroll is<br />

i<strong>nd</strong>eed godless, but so is the novel as a whole-no character is a touchstone of<br />

grace, for Elinor's religiosity is merely an aspect of her placability a<strong>nd</strong><br />

obedience. As is usual in Clive's novels, the moral reflections are left for the<br />

reader to infer. The narrator preserves some, though not all, of the detachment<br />

maintained rn Paul Fenoll. The plot, being less ambiguous, re<strong>nd</strong>ers more<br />

explicit the reflections on the selfishness of Leslie a<strong>nd</strong> Laura, a<strong>nd</strong> this is<br />

accompanied by authorial comments to that effect. Yet, though it is clear that<br />

our sympathies are to be with Elinor, against Laura, a<strong>nd</strong> partly for Leslie, the<br />

story is told by an omniscient narrator whose interest is evenly shared between<br />

the three characters, a<strong>nd</strong> is told dramatically, mostly in dialogue a<strong>nd</strong> action, so<br />

as to postpone the moral implications to some area outside the reading process.<br />

Nevertheless the innocence of the seco<strong>nd</strong> wife a<strong>nd</strong> the cruelty a<strong>nd</strong> selfishness<br />

of the first are heavily stressed, a<strong>nd</strong> Fenoll/Leslie himself is portrayed as at<br />

once arrogant a<strong>nd</strong> sensitive in a way which is consistent with his later<br />

behaviour in Paul Fenoll.<br />

Like Clive's other novels it is short, with few characters, a<strong>nd</strong> few<br />

episodes, a<strong>nd</strong> its best features are the dry narrative voice a<strong>nd</strong> the moments of<br />

observant irony. Laura/Anne is a stock character of selfish worldliness, a<strong>nd</strong><br />

her machinations, involving forged notes a<strong>nd</strong> false assignations, are extremely<br />

hackneyed, but Clive shows her customary interest in abnormal states of mi<strong>nd</strong><br />

in depicting Laura's jealousy:<br />

She learned to know that beating heart, that dry mouth, that distaste to<br />

food, that early waking a<strong>nd</strong> no more falling asleep, which make up the<br />

personal sufferings of mental anguish. She had to talk, to listen, to make<br />

music, while intensely preoccupied ... (47)<br />

Though some readers seem to have thought so, it would not be accurate to say<br />

that this novel is a clearer co<strong>nd</strong>emnation of Ferroll's character than the other,<br />

but as before he is the object of the occasional authorial irony:<br />

"How moveable her nature is," said he. "It was made on purpose, I<br />

think, to complete mine, cast in my mould, when a man had been<br />

completed, a<strong>nd</strong> it was fit only to form a woman." (140)<br />

There are some touches of feminist feeling: Laura says, "'I could have<br />

laughed at times to think how the great, tle manly intellect yielded to despised<br />

woman."' (316), a<strong>nd</strong> at the e<strong>nd</strong> we are told that "He was fast bou<strong>nd</strong> in the<br />

meshes, which a woman, a mere woman, had fou<strong>nd</strong> the means to twine arou<strong>nd</strong><br />

him" (332). Three women, in fact, the author, Laura a<strong>nd</strong> Elinor, have by the<br />

e<strong>nd</strong> tied him down, Clive by inventing him a<strong>nd</strong> thus in a way acquiring his<br />

self-confidence a<strong>nd</strong> the genius ascribed to him. Though he does not dominate<br />

this book quite as he did Paul Ferroll, he is the central character, a<strong>nd</strong> his<br />

brilliance a<strong>nd</strong> authority are much referred to, though less convincingly evoked<br />

than in that novel. His literary genius is attested to by the fact that he has<br />

written Clive's early poem "The Grave" (151).<br />

Wy Paul Ferroll Killed His Wife has some of the properties of a short<br />

story, being elliptical, theatrical, striking a<strong>nd</strong> brief. It is unique :rmong Clive's<br />

novels in that it contains no violent crime or frightful death, but its title,<br />

promising both, kept it on the railway station bookstalls throughout the<br />

century. Though it suffered the fate of most sequels a<strong>nd</strong> was adjudged inferior<br />

to Paul Fenoll, it was approved by some reviewers. The Saturday Review<br />

thought it written by a "pen of genius" a<strong>nd</strong> that it made reparation for the<br />

"ambiguity of tone" in the earlier novel.23 The Examiner objected to the<br />

"purely narrative' method adopted by the novelist, but thought that within the<br />

limitations of such a technique she had shown 'rare a<strong>nd</strong> precious" strengths.24<br />

Some critics were impressed with the coherence of the two-part story,<br />

including the Rev. James Davies:<br />

A tragedy, in its entirety worthy to be classed with the intensely wrought<br />

creations of the Greek drama; a tragedy evoking strongest sentiments of<br />

i<strong>nd</strong>ignation, pity, a<strong>nd</strong> sympathy; a tragedy in which, though convention<br />

will not suffer us to justif, the chief actor, yet every one agrees that the<br />

wretched successor of the Clytemnestras a<strong>nd</strong> Lady Macbeths of the<br />

ancient a<strong>nd</strong> modern drama deserved her fate, or even a worse.2s<br />

Classical tragedy offered a convenient analogy: "we feel that we are in the<br />

unrelenting grasp of a Greek fate ..." wrote William Allingham.26 If the novels<br />

were inte<strong>nd</strong>ed to depict a long-drawn-out cycle of inevitable retribution,<br />

Ferroll's outrageous behaviour can be seen as elemental, Clive's starkness as<br />

19

20<br />

strength. The dearly-held conviction that the universe is ultimately orderly a<strong>nd</strong><br />

providential, which Clive's novels, so unusually at this date, seem to<br />

u<strong>nd</strong>ermine, could be surreptitiously reasserted. Guided, surely, by such<br />

feeling, Florence Nightingale wrote to Clive:<br />

So far from "not liking" your book, it interested me extremely. To the<br />

truth of Paul Ferroll's character I can testify from personal experience.<br />

... But I think as a work of art it is now lop-sided. It ought to be like a<br />

Greek Trilogy ought it not? Ought there not to be a third part, shewing<br />

what Janet the offspring of those two characters, became, a<strong>nd</strong> what Paul<br />

Ferroll himself became in his old age. I think this would be the most<br />

curious a<strong>nd</strong> interesting part of all.27<br />

Clive gratified Nightingale's curiosity, but in a letter which apparently does<br />

not survive, a<strong>nd</strong> the public was not vouchsafed another sequel.28<br />

In 1864 Clive published the last, least noticed, a<strong>nd</strong> perhaps oddest, of all<br />

her novels, John Greswold. The hero, younger son of a poor gentry family,<br />

tells the story. He is first articled to an attorney, who drops down dead in a<br />

gaming house leaving the narrator a fortune which he nobly resigns to his<br />

employer's family. He falls in love, becomes a la<strong>nd</strong> agent, witnesses the<br />

unsuccessful romances of his brother a<strong>nd</strong> his new employer, a<strong>nd</strong> has no better<br />

luck in love himself. The novel e<strong>nd</strong>s with him still ignorant of what the future<br />

holds, a<strong>nd</strong> the reader no wiser. Her calm a<strong>nd</strong> ironic style was praised by<br />

reviewers in the Examiner a<strong>nd</strong> the Saturday Review, who saw the novel as a<br />

ki<strong>nd</strong> of still life: "less a novel than what the French call an 6tude" .2e But these<br />

were exceptional; the novel was little noticed a<strong>nd</strong> never reprinted. Like Paul<br />

Fenoll a<strong>nd</strong> Year after Year it e<strong>nd</strong>s with a central character speaking, on a note<br />

of i<strong>nd</strong>eterminacy:<br />

Twenty-three years ago I was born into this world, a<strong>nd</strong> now the twentythird<br />

is run out. The time is gone; the known things are all over, all<br />

buried in the darkness behi<strong>nd</strong>. Before me lies the great blank page of the<br />

future, a<strong>nd</strong> no writing is traced upon it. But it is nothing to me; I won't<br />

ask, nor think, nor hope, nor fear about it. The leaf of the book is<br />

turned, a<strong>nd</strong> there's an e<strong>nd</strong>-the tale is told. (ll,2l9)<br />

Clive's detached authorial technique, brought to bear in both Paul<br />

Ferroll a<strong>nd</strong> Wy Paul Ferroll Killed His Wife on a retribution plot with a<br />

recognizable pattern, encounters tnJohn Greswold a story nearly as formlessly<br />

serial as realiry, to curious effect. There is an absence of authoritative closure<br />

which is formally disruptive-there are pathos, humour, melodrama a<strong>nd</strong> the<br />

Characteristic tension in John's story, but no resolution. Clive's customary<br />

unwillingness to provide a point of authority reaches a peak in the last chapter<br />

with the revelation that the autobiographer has nearly reached the reader's own<br />

time, so ttrat the story exists like the reader on the edge of ignorance of the<br />

future:<br />

It was the 5th of last February, a night, as the reader will recollect, of<br />

severe frost; the thermometer was down below zero fifteen degrees in<br />

the Southern counties. (ll,2l7)l<br />

There is an intrusion of reality which makes the statement desultory,<br />

conversational. The weather has at this point none of the significance one<br />

anticipates in a nineteenth-century novel, where it usually functions<br />

symbolically, or affects characters or action. Here it simply demonstrates, as<br />

do other episodes in the novel, the inexplicable hazards of experience. Just as<br />

Katherine Buckwell's household arrangements were reorganized by others, so<br />

John Greswold is forced to realize the failure of his attempt to bring Pattern to<br />

his life. His story tails off, as real autobiographies so often do, into anecdote,<br />

because no plot can be detected in recent or current experience. Novelists,<br />

however, generally i[range that closure will take place at some significant<br />

moment: the breaking-off will affect our interpretation of the preceding story.<br />

Thus e<strong>nd</strong>ing a<strong>nd</strong> morality are intimately connected, a<strong>nd</strong> Clive's eccentric<br />

treatment of her last hero is the final expression of her i<strong>nd</strong>ifference to the<br />

literary proprieties.<br />

The freshness which her contemporary admirers conrmented on derives<br />

partly from this feahrre of her work. one might argue that it is as much a<br />

-onsequence of incompetence as of a deliberate attempt to break the mould of<br />

mid-Victorian convention; a certain amateurishness u<strong>nd</strong>oubtedly clings to her<br />

fiction. Yet her eccentricities were ones which had imporant implications for<br />

the future of the novel: having a murderer for a hero; having a plain spinster<br />

for a heroine; e<strong>nd</strong>ing novels without telling the reader what has happened a<strong>nd</strong><br />

what it means; e<strong>nd</strong>ing two autobiographies with neither death nor marriage;<br />

writing very short fictions. By the e<strong>nd</strong> of the century some of these aberrations<br />

were cornmonplaces: the three-decker was dead, a<strong>nd</strong> literary morality had been<br />

transformed.<br />

$$s$$$$$$$$$<br />

Unlike many of the women who embarked on literary careers during the<br />

nineteenth century, Clive was not out to make money. She was gratified to<br />

receive her small eamings, but they were never significant to the family<br />

2l

BFI'<br />

22<br />

income, a<strong>nd</strong> her decision to publish was uninfluoncod by financial<br />

considerations. This fact is highly significant. One cannot know whethcr, had<br />

she published more a<strong>nd</strong> been u<strong>nd</strong>er pressure to respo<strong>nd</strong> to tho doma<strong>nd</strong>s of the<br />

market, the oddity of her style would have been modiflod for bottcr or for<br />

worse-whether she would have refined it, or degenerated into a mere hack.<br />

Speculation on this point is profitless. But her carcer affords somc interesting<br />

sidelights on the profession of authorship in her time.<br />

All discussion of authorship a<strong>nd</strong> literary genius in the nincteenth century<br />

was pervaded by the languages of ge<strong>nd</strong>er a<strong>nd</strong> class. Clivo's own remarks on<br />

the subject are no exception to this rule-two women writers of her<br />

acquaintance were described as having "something nameless about them which<br />

was Authoress more than Lady'3o Her early letters to men of letters, full of<br />

ambition, signed with male pseudonyms, i<strong>nd</strong>icate aspirations towards an ideal<br />

of Poetic Genius not wholly congruous with her identity as a lame young lady<br />

of the la<strong>nd</strong>ed gentry. Reviewers of her work respo<strong>nd</strong> to the same sense of<br />

discrepancy when they praise it for its unfeminine virtues:<br />

.... these few pages are distinguished by a sad Lucretian tone, which very<br />

seldom comes from a woman's lyre.3t JOf IX Poems by V.l<br />

... the distinctive features of V.'s poems are virile force a<strong>nd</strong> a stern<br />

simplicity.32 [Of Poems, 18721<br />

Similarly, when her first novel Paul Fenoll (1855) came out, reviewers were<br />

to praise the power of its writing a<strong>nd</strong> marvel at the sex of its author. One<br />

should not exaggerate the significance of this-sales of her poetry were never<br />

considerable, a<strong>nd</strong> until 1855 she was not a well-known writer. But had she<br />

been less isolated from the literary market-place, had she, for instance, tried to<br />

earn her living selling verse to illustrated annuals as Caroline Norton did, she<br />

might have developed a more sentimental, picturesque a<strong>nd</strong> lyrical strain. She<br />

might sooner have tried her ha<strong>nd</strong> at a novel. But, financially i<strong>nd</strong>epe<strong>nd</strong>ent, she<br />

could i<strong>nd</strong>ulge a fantasy of herself as a Poet transce<strong>nd</strong>ing barriers of ge<strong>nd</strong>er,<br />

while being cautious of those whose circumstances, less socially secure, forced<br />

them to try a<strong>nd</strong> reconcile the roles of Authoress a<strong>nd</strong> Lady:<br />

She [Caroline Norton] was anxious to please & to flatter-why should<br />

she be except that she feels her position doubtful [?] however, exciting<br />

& new as her sociefy is, I was delighted to get o[u]t lofl it.33<br />

It is customary to think of the ge<strong>nd</strong>er prejudice of Victorian readers as<br />

being a ha<strong>nd</strong>icap to women writers. However, it seems clear in Clive's case<br />

it<br />

I<br />

thst the unexpected qualities of her writing were recognized partly because she<br />

was known to be a woman. Reviewers of PauI Ferroll were conscious of<br />

surprise that a woman should publish such a book, a<strong>nd</strong> the terms in which they<br />

refer to this point i<strong>nd</strong>icate that their assumptions about women a<strong>nd</strong> writing<br />

te<strong>nd</strong>ed on the whole to impress them with Clive's literary skill:<br />

We are the more ready to canvass the strange moral of this story from<br />

deference to the remarkable power with which it is written, a<strong>nd</strong> which is<br />

the more remarkable still if its author be a lady.3a<br />

We are naturally anxious lest the masculine nerve pass wholly from our<br />

letters .... We must needs look askance at the maudlin effeminacy that is<br />

stealing in [to English fiction] .... Yet, on the other ha<strong>nd</strong>, we cannot<br />

wholly sympathize with the unfeminine strides of a Mrs. Shelley or a<br />

Mrs. Clive ...35<br />

A complex of prejudices surrou<strong>nd</strong>ed the ideas of genius, immorality a<strong>nd</strong><br />

fenrininity. Growing numbers of women writers led to an anxiety about their<br />

influence on English literature, although they were acknowledged as the<br />

guardians of mid-Victorian social morality. Deeply as most reviewers believed<br />

in that morality, they worried whether its rigour sorted well with genius. As<br />

Fitzjames Stephen observed in 1857, "surely it is very questionable whether it<br />

is desirable that no novels should be written except those fit for young ladies to<br />

read?'36 Justin MacCarthy echoed him in 1864, disparaging novelists who<br />

"coldly, stiffly, prudishly agreed to paint for us as a rule only such life as<br />

might be lectured on in a young ladies'boarding school".37 Just as in 1840<br />

Caroline Clive's verse was seen as possessing strengths in comparison with the<br />

sentimental lyrics turned out by ladies for publication in illustrated annuals, so<br />

in the 1850s, her first novel was favourably contrasted with the domestic<br />

realist novels then dominating the market. A<strong>nd</strong> in both cases a ge<strong>nd</strong>ered<br />