2006 Edition 2 (Issue 144) - Sasmt-savmo.org.za

2006 Edition 2 (Issue 144) - Sasmt-savmo.org.za

2006 Edition 2 (Issue 144) - Sasmt-savmo.org.za

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

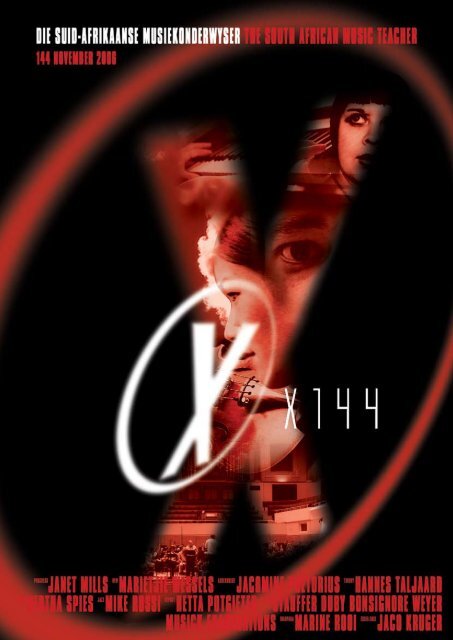

South African Music Teacher |<strong>144</strong> | November <strong>2006</strong>

Suid-Afrikaanse Musiek Onderwyser |<strong>144</strong> | November <strong>2006</strong>

South African Music Teacher |<strong>144</strong> | November <strong>2006</strong><br />

UKUSA is based at the Durban campus of UKZN. It is a developmental<br />

community performing arts NGO for students sixteen<br />

years and older. It offers beginner’s tuition in music, dance, and<br />

drama. Initiated in 1987, UKUSA was one of the first local arts outreach<br />

programmes for historically disadvantaged people in Kwa-<br />

Zulu-Natal. About 300 students take lessons in keyboards, trumpet,<br />

saxophone, lead guitar, bass guitar, maskanda, drumming,<br />

dance, drama, choir and music theory. At the end of each year<br />

certificates of merit are awarded to successful students. UKUSA<br />

aims to help students who show willingness to work, ability in the<br />

creative arts, and a desire to share what they have learned with<br />

others in their communities.

t h e s o u t h a f r i c a n m u s i c t e a c h e r ~ d i e s u i d - a f r i k a a n s e m u s i e k o n d e r w y s e r<br />

editor ~ redakteur<br />

Hannes Taljaard<br />

business manager ~ bestuurder<br />

Annette Massyn<br />

copy editor ~ kopie-redakteur<br />

Jaco Kruger<br />

directory editor ~ ledelysredakteur<br />

Hubert van der Spuy<br />

advertising manager ~ advertensies<br />

Annette Massyn<br />

editorial assistants ~ redaksionele assistente<br />

Danell Herbst<br />

Elize Verwey<br />

design & layout ~ ontwerp & uitleg<br />

Polar Design Solutions<br />

(082 770 5734)<br />

info@polard.com<br />

reproduction & printing<br />

d.comm.<br />

(018) 290 5554<br />

distribution ~ verspreiding<br />

Prestige Bulk Mailers<br />

(011) 708-2324<br />

postal address ~ posadres<br />

SA Music Teacher<br />

PO Box 20573, Noordbrug 2522<br />

South Africa<br />

Tel. +27 (0)18 299 1702<br />

musdjt@nwu.ac.<strong>za</strong><br />

http://www.samusicteacher.<strong>org</strong>.<strong>za</strong>/magazine<br />

physical address ~ fisiese adres<br />

Conservatory ~ Konservatorium<br />

Van Der Hoff Road, Potchefstroom 2531<br />

South Africa<br />

directory lists ~ ledelyste<br />

Directory Editor ~ Ledelysredakteur<br />

PO Box 36242, Menlo Park 0102<br />

Fax. (012) 429-3644<br />

vdspuhh@unisa.ac.<strong>za</strong><br />

The South African Music Teacher is the official <strong>org</strong>an of<br />

the South African Society of Music Teachers (SASMT). It is<br />

published and distributed biannually in the interest of music<br />

and Southern African musicians. The SASMT is an association<br />

not for gain incorporated in terms of Section 21 of the 1974<br />

Companies Act, and all following amendments to the same,<br />

and applies its income to the promotion of its goals.<br />

Reg. no. 1932/004247/08<br />

ISSN:0038-2493<br />

Copyright © <strong>2006</strong>, South African Music Teacher<br />

All rights reserved<br />

No article, picture or portions thereof in this magazine may<br />

be reproduced, copied or transferred in any form whatsoever<br />

without the express written consent of the writer(s) and the<br />

editor. Contributors keep the intellectual property rights to<br />

their work.<br />

Opinions expressed in this magazine are not necessarily those<br />

of the editor, publisher, the SASMT, sponsors or advertisers.<br />

The South African Music Teacher is indexed in the Music Index<br />

and the International Index to Music Periodicals.<br />

p r e a m b l e<br />

There are x-chromosomes which<br />

we all have (some twice as many<br />

as others); x-rays which are<br />

useful, but also harmful if we are<br />

exposed to them without proper<br />

care; and The X-Files of which<br />

each episode is supposed to<br />

baffle us until the end when we sometimes feel a huge<br />

sense of relief. Many of us have xses (and many have too<br />

many) whom most of us would prefer not to experience<br />

again.<br />

Then there are x-<strong>za</strong>ms. Many musicians have (had)<br />

them (some many more than others) — they are useful,<br />

but can be harmful; they certainly baffle most of us,<br />

and only when they are over do we sometimes feel a<br />

great sense of relief. Many of us would prefer not to<br />

experience them again.<br />

Thirty years ago evolutionary biologist Richard<br />

Dawkins made himself a couple of friends and more<br />

than a few enemies when he published his book The<br />

Selfish Gene, in which he argued that the reason for<br />

our existence — and those of all living creatures — is<br />

simply to serve as survival machines that ensure the<br />

preservation of replicators, those egotistic molecules<br />

known as genes. Dawkins’s idea of the selfish gene<br />

found its way into the minds of many thinkers and so<br />

did another, even more controversial idea: the selfish<br />

meme. Memes would be the cultural equivalent of<br />

genes and our minds — simply meme machines.<br />

I toyed with these ideas when trying to understand<br />

this perplexing phenomenon of music exams. I must<br />

confess to having strong and contradicting feelings<br />

about music exams, and to being unable to make up<br />

my mind. Sometimes we seem to be taking exams,<br />

and often we seem to be taken hostage by them. So I<br />

have been asking myself: might those music exams be<br />

pernicious examples — indeed proof — of the theory<br />

of the selfish meme? Or are they responsible ways to aid<br />

the progress of our learners?<br />

The editor would like to include many voices in The<br />

South African Music Teacher. If you are interested in contributing<br />

to the magazine, please contact the editor via<br />

email for advice and guidelines on the editorial process<br />

and the format of articles and reviews. Contributions will<br />

most likely be edited to suit the vision, style and format of<br />

the magazine. Please send photos and graphics as hard<br />

copies and/or electronically as cmyk jpeg with a resolution<br />

of at least 300 dpi and a compression ratio not less than 8.<br />

Suid-Afrikaanse Musiek Onderwyser |<strong>144</strong> | November <strong>2006</strong>

4 preamble<br />

8 editorial<br />

9 letters<br />

features ~ artikels<br />

12 Michael Whiteman<br />

— Reino Ottermann<br />

14 assessing progress in music<br />

— Janet Mills<br />

17 dis te ver om te ry...<br />

— Marietjie Wessels<br />

20 no more hating theory<br />

— Jacomine Pretorius & Hannes Taljaard<br />

24 Waar is die musiek in die musiekteorie?<br />

— Bertha Spies<br />

27 the jazz exam dilemma<br />

— Mike Rossi<br />

43 the music faculty of the NIHE<br />

— Faan Malan<br />

news ~ nuus<br />

7&9 SASMT AGM<br />

10 scholarship winners<br />

11 the <strong>2006</strong> Sanlam competition<br />

26 AGM <strong>2006</strong><br />

26 ISME<br />

40 honorary members<br />

52 SAMRO Scholarship winners<br />

53 Oemf<br />

design: Heilene Oosthuizen<br />

(Polar Design Solutions)<br />

South African Music Teacher |<strong>144</strong> | November <strong>2006</strong><br />

c o n t e n t s ~ i n h o u d<br />

7, 33, 37, 49, 51, 55 reviews<br />

39, 40, 51 resources<br />

56 subscription form<br />

report ~ verslag<br />

36 reader’s survey — Hetta Potgieter<br />

reviews ~ resensies<br />

29 W. Meuris et al. Speel Viool!<br />

— Estelle Stuaffer<br />

29 P. Murray. Essential Bass Technique<br />

— Marc Duby<br />

30 M. Dartsch. Der Geigenkasten<br />

— Estelle Stauffer<br />

31 P. Inglis. Guitar Playing and How it Works<br />

— Jenny Bonsignore<br />

32 S. Bernstein. With Your Own Two Hands<br />

— Waldo Weyer<br />

46 Starting and Running a music studio<br />

— Hannes Taljaard<br />

columns ~ rubrieke<br />

41 in diaspora<br />

— Mariné Rooi<br />

50 PG: an emphasis on performance<br />

— Janet Mills<br />

opinion ~ opinie<br />

34 in pursuit of excellence — Jaco Kruger<br />

competitions ~ kompetisies<br />

26 Music Giveaway #143: winners<br />

26 Reader’s Survey: winners<br />

47 Music Giveaway #<strong>144</strong>

Suid-Afrikaanse Musiek Onderwyser |<strong>144</strong> | November <strong>2006</strong>

Universal <strong>Edition</strong> produced Soundsnew. 19 Easy<br />

Piano Pieces (ISBN: 3-7024-2921-2) edited by Peter<br />

Roggenkamp. The technical demands of the pieces correspond<br />

to Books II and III of the Mikrokosmos. Roxanne<br />

Panufnik, Johannes Maria Staud and Ian Wilson wrote<br />

works specifically for this collection, while pieces by<br />

Bartók and Webern, as well as by Jenö Takács, Karl Heinz<br />

Füssl, Friedrich Cerha, György Kurtág, Anthony Hedges,<br />

Arvo Pärt, Peter Roggenkamp, and Richard Rodney Bennet<br />

are also included. Notes on all the composers are<br />

included in German, English and French. Since new<br />

techniques and notation are gradually introduced, this<br />

collection can form part of a very interesting discovery<br />

of new music by young pianists.<br />

South African Music Teacher |<strong>144</strong> | November <strong>2006</strong><br />

r e v i e w s ~ r e s e n s i e s<br />

Well-known British pianist Joanna MacGregor’s edition<br />

of twelve contemporary pieces for piano — Unbeaten<br />

Tracks — is published by Faber Music (ISBN: 0-571-<br />

52409-5). It is indeed a pleasure to notice so many<br />

unfamiliar names on the cover: Parricelli, Mukaiyama,<br />

Lodder, Hinde, McGarr and a few more. MacGregor<br />

writes in the introduction: “I asked a group of creative,<br />

talented musicians to come up with pieces that would<br />

not only stretch you technically, but would also give you<br />

other important things — a sense of groove, the chance<br />

to improvise, music that would unlock your imagination.”<br />

My impression is that the ‘you’ here refers to pianists<br />

from about Grade IV to Grade VII level. The ‘biopics’<br />

of the composers and their realisations in sounds are<br />

fascinating, and well-worth investigating.

t h e s o u t h a f r i c a n s o c i e t y o f m u s i c t e a c h e r s ~ d i e s u i d - a f r i k a a n s e v e r e n i g i n g v a n m u s i e k o n d e r w y s e r s<br />

president<br />

Dr Tim Radloff<br />

president-elect ~ aangewese president<br />

Prof Hubert van der Spuy<br />

past-president ~ uittredende president<br />

Mev Marie Gaerdes<br />

vice-president ~ vise-president<br />

eastern cape ~ oos-kaap<br />

Mr Pierre Malan<br />

vice-president ~ vise-president<br />

kwazulu-natal<br />

Dr Ros Conrad<br />

vice-president ~ vise-president<br />

transvaal & free state ~ vrystaat<br />

Mev Riètte Swart<br />

vice-president ~ vise-president<br />

western cape ~ weskaap<br />

Mr Leon Hartshorne<br />

executive officer ~ uitvoerende beampte<br />

Mr Jaco van der Merwe<br />

executive committee ~ uitvoerende komitee<br />

Dr Tim Radloff (president)<br />

Ms Carolyn Stevenson-Milln<br />

(minuting secretary ~ notule)<br />

Ms Mandy Carver<br />

Ms Jillian Haarhoff<br />

Mr Pierre Malan<br />

Mr Ian Smith<br />

standing committee ~ vaste komitee<br />

Mr Hannes Taljaard (chair ~ voorsitter)<br />

Mr Jaco van der Merwe<br />

(executive officer ~ uitvoerende beampte)<br />

Ms Dikonelo Booysen<br />

Mrs Estelle Stauffer<br />

honorary members ~ ere-lede<br />

Mrs Noreen Currie, Ms Inga Heineberg, Ms Diane Heller, Mr<br />

Ivan Killian, Prof Rupert Mayr, Prof Reino Otterman,<br />

Prof Hubert van der Spuy, Prof Michael Whiteman<br />

official correspondence ~ amptelike korrespondensie<br />

Executive Officer SASMT ~ Uitvoerende Beampte SAVMO<br />

PO Box 20573<br />

Noordbrug 2522<br />

South Africa<br />

tel./fax. +27 (0)18 299-1699<br />

sasmt@samusicteacher.<strong>org</strong>.<strong>za</strong><br />

http://www.samusicteacher.<strong>org</strong>.<strong>za</strong>/<br />

e d i t o r i a l<br />

I think most people discover somewhere near the start of<br />

their careers that it is almost as easy to criticize as it is<br />

difficult to develop and implement improvements. This<br />

can have the paralyzing result that we simply accept the<br />

status quo and keep on doing things the way they have<br />

been done, without reflecting upon the outcomes of our<br />

actions. This is clearly not a suitable course of action for<br />

educators.<br />

The difficulty of evaluating and improving current practices<br />

should not make us reluctant to criticize where criticism<br />

is due. The unpleasant (for most) experience of receiving<br />

criticism should not seduce us into ostracising those who<br />

dare speak their minds. It is easier to live together cosily,<br />

but it is not conducive to growth and excellence. We need<br />

a bit of sibling rivalry, and often criticism highlights what<br />

is good and gives more energy for further improvements.<br />

Sometimes pupils are taught exams, not music — this is<br />

not the fault of the examination boards.<br />

When educators are trying to produce good and happy<br />

cooks, here is what they will not do. Make the child choose<br />

four recipes. These recipes should be from four different<br />

countries, but the child should not have clear ideas about<br />

the culture of those countries. Have them practise incessantly<br />

only these four recipes at home for eight months;<br />

taking them to cooking lessons once a week. They may be<br />

allowed to make a sandwich once in a while, but do not<br />

confuse them. Now get some background into their heads.<br />

Make them endlessly copy a few other recipes. Be inventive:<br />

leave out certain words and then teach them rhymes<br />

and riddles so that they will know which words were left<br />

out. Above all, make them count the letters, and show<br />

them the dresses of the people in those foreign countries.<br />

Do not f<strong>org</strong>et — they should memorise the names of those<br />

dresses: kimono, sarong, kilt, kikoy, aba, camis. It does not<br />

really matter if the pictures are old and not so realistic. If<br />

you do not have pictures of the dresses, the children should<br />

still know all the names. Then have them take a cooking<br />

examination during which the cooking teacher should<br />

look worried, as if their self-esteem depended upon the<br />

outcome of this examination.<br />

One often hears criticism of music examinations. “It’s all<br />

UNISA’s fault.” Is it? I think not. Music educators, be they<br />

private or part of an institution, have considerable freedom<br />

— and responsibility — to choose what they do before and<br />

after music examinations which for most pupils are played<br />

and/or written but once a year. The problems in music<br />

education in South Africa is less the result of the presence<br />

of music exams and more the necessary consequences of<br />

our teaching strategies. Improvements of strategies can<br />

happen when we are learner-centered and when we try<br />

to establish authentic musical contexts for the activities of<br />

our pupils. Examinations can be part of a healthy music<br />

education, but never the only or the most important one.<br />

Suid-Afrikaanse Musiek Onderwyser |<strong>144</strong> | November <strong>2006</strong>

Thank you for my copy of issue 143 of the South<br />

African Music Teacher. It is full of interesting and informative<br />

articles. The contents, layout and general<br />

production have given us a magazine of the highest<br />

quality and one of which the SASMT can be truly<br />

proud. Congratulations.<br />

There are, however, some points that cause concern.<br />

The magazine belongs to the members of the<br />

SASMT. Society developments and activities are of<br />

interest to them and many would welcome space<br />

being allocated to bringing some of these to their<br />

attention.<br />

In March / April 2005, the Annual Conference<br />

took place in Natal. Apart from Marie Gaerdes’s<br />

thought provoking presidential address, there is no<br />

further mention of the conference. Several important<br />

matters were discussed and decisions taken. Interesting<br />

papers were read and master classes were<br />

presented by leading members of the society. Facts<br />

regarding resolutions passed and short reviews of<br />

other activities would surely encourage a higher<br />

attendance at future conferences. Part of the time<br />

was devoted to the election of new office bearers.<br />

These are of utmost importance for the well–being<br />

and future of the SASMT, but few of our members<br />

are aware of the results.<br />

Since 2004, three prominent members, Prof<br />

Rupert Mayr, Prof Hubert van der Spuy and Mr Ivan<br />

Kilian have been awarded honorary membership.<br />

This is the greatest honour the society can bestow<br />

and is surely worthy of a photograph and some biographical<br />

notes appearing in the magazine. Reading<br />

of the achievements of these senior members could<br />

well lead to the formation of role models for ex students<br />

and less active members, which is something<br />

our society desperately needs.<br />

Diane Heller, Johannesburg Centre<br />

Artikels, resensies en nuus kan in enige van die amptelike<br />

landstale geskryf word. Bydraes word geplaas in die taal<br />

waarin dit ontvang word. Voorstelle oor die ingewikkelde<br />

taalkwessies is altyd welkom.<br />

n e w s ~ n u u s<br />

Improvisation Re-visited<br />

South African Music Teacher |<strong>144</strong> | November <strong>2006</strong><br />

l e t t e r s ~ b r i e w e<br />

Baie geluk met ‘n puik tydskrif. Die voorkoms, samestelling<br />

en leesinhoud beïndruk en ek vind die artikels,<br />

spesifiek dié oor die Alexandertegniek baie insiggewend<br />

en leersaam. Ek sien met afwagting uit na die volgende<br />

uitgawe vir nog interessante leesstof.<br />

Marietjie Renison, Parys<br />

Voor ek die laaste uitgawe van Die Suid-Afrikaanse<br />

Musiekonderwyser in die hand gehad het, was ek nie ‘n<br />

gereelde leser daarvan nie. Dit het nou verander. Die<br />

tydskrif lyk so goed, en wanneer ‘n mens begin deurblaai<br />

is dit duidelik dat dit nie net aanbieding is waaraan<br />

julle aandag gee nie. Die tydskryf het ‘n samehang en<br />

variasie van inhoud wat geen klein prestasie is nie. En dit<br />

behandel temas en bring inligting aan die bod waarvan<br />

ek nie andersins sou kennis neem nie. Alles baie professioneel<br />

en vakkundig solied. Bravo! Ek sien uit na die<br />

volgende uitgawe.<br />

Stephanus Muller<br />

Is there something in the magazine that you find<br />

informative, provocative, challenging, annoying or even<br />

infuriating? Maybe you would like us to remove some<br />

content or change some aspect of the magazine’s layout.<br />

Did this issue of the magazine connect, inform, challenge<br />

and support you?<br />

Your letter can help The South African Music Teacher<br />

and the South African Society of Music Teachers to reach<br />

important goals. Your opinions can move people to look<br />

differently at their own situations. If your letter is considered<br />

for publication, you will be consulted.<br />

The best letter will earn a R200<br />

gift voucher to be used at<br />

Write to: The South African Music Teacher, PO Box 20573,<br />

Noordbrug 2522, South Africa<br />

Fax. (018) 299 1699 / musdjt@nwu.ac.<strong>za</strong><br />

The AGM and conference of the South African Society of Music Teachers will take place at Rhodes University in<br />

Grahamstown from 2 to 5 April 2007. Please send suggestions and submissions for contributions before 15 January<br />

to the president: t.radloff@ru.ac.<strong>za</strong>.<br />

Die algemene jaarvergadering en konferensie van die Suid-Afrikaanse Vereniging van Musiekonderwysers sal plaasvind<br />

vanaf 2 tot 5 April 2007 by die Rhodes Universiteit in Grahamstad. Stuur voorstelle vir bydraes voor 15 Januarie<br />

aan die president: t.radloff@ru.ac.<strong>za</strong>.

n e w s ~ n u u s Musiekkamp Beurse 2005 & <strong>2006</strong><br />

Twee jong Suid-Afrikaanse musici het in 2005 en <strong>2006</strong> die musiekkamp in Bottineau, Noord Dakota, by die International<br />

Peace Gardens op die grens van Kanada bygewoon.<br />

Deo du Plessis (2005)<br />

Hierdie jong perkussiespeler van Pretoria was een van ongeveer 200 leerlinge<br />

waarvan 35 van buite die VSA afkomstig was. Die personeel van ongeveer<br />

vyfhonderd het wêreldberoemde leermeesters en dirigente ingesluit. Deo is<br />

gekies as leier van die perkussieseksie in beide die International Youth Band en<br />

die International Wind Ensemble. Hy het ook vir ‘n week lank deelgeneem aan die<br />

marimba en vibrafoon kursus, verskeie meestersklasse ontvang, en as solis saam<br />

met ensembles opgetree.<br />

Gedurende die twee weke het Deo saam met 120 ander musici deelgeneem aan<br />

‘n World’s Fastest Drummer kompetisie. Hy was die algehele wenner en kon die<br />

meeste note binne dertig sekondes op ‘n spesiale trom speel! Deo was verder een<br />

van net dertig leerlinge wat ‘n Outstanding Camper-sertifikaat ontvang het.<br />

Deo is hierdie jaar in matriek aan Pretoria Boys High waar hy as dux-leerling ook<br />

die toekenning vir die beste musiekstudent van 2002 tot <strong>2006</strong> ontvang het. Hy<br />

het hierdie jaar sy graad VIII perkussie-eksamen met lof geslaag en deelgeneem<br />

aan die UNISA beurskompetisie op 13 Oktober waar hy een van nege musici in die finale rondte was. Hy was ook die<br />

dux-leerling by Pro Arte Alphen Park se Musiekakademie. Deo beplan om volgende jaar meganiese ingenieurswese<br />

te studeer, maar steeds in ensembles en bands betrokke te wees. Hy wil graag na voltooiing van sy studies in Amerika<br />

sy studies in perkussie — veral ligte musiek — voortsit.<br />

Annelize de Villiers (<strong>2006</strong>)<br />

Annelize het in 1999 by die Hugo Lambrects Musiekskool onder Elize Nel met<br />

klarinetonderrig begin. Sedert 2001 ontvang sy verdere onderrig by Charlene<br />

Verster. Sy het al haar eksamens met lof geslaag en verskeie cum laude diplomas<br />

by die Stellenbosch Eisteddfod ontvang. Sy het al in verskeie ensembles en<br />

orkeste gespeel: Hugo Lambrechts Simfoniese Blaasorkes (2003, 2004), Nasionale<br />

Jeug Simfoniese Blaasorkes (2004), Hugo Lambrechts Simfonie Orkes (2004),<br />

en die Hugo Lambrechts Houtblaaskwintet. In 2005 word sy genooi om aan die<br />

Stellenbosch Internasionale Kamermusiekfees deel te neem en slaag haar UNISA<br />

Graad VII eksamen met 86%.<br />

Sy het vir twee weke deelgeneem aan die International Youth Band Program waarin<br />

sy eerste klarinet en seksieleier was in beide die International Youth Band en die<br />

Honour Band. Een van die dirigente — Dr. Reed Thomas, Director of Bands by Middle<br />

Tennessee State University het haar genooi om aan sy universiteit te kom studeer.<br />

Hulle het daagliks vir ‘n uur meestersklasse gehad, en sy het ook beide weke in<br />

‘n houtblaaskwintet gespeel wat elke dag vir ‘n uur geoefen het, en ‘n paar keer uitvoerings gelewer het. Sy het drie<br />

toekennings ontvang: Outstanding Music Camper, Outstanding Achievement by a Band Member (wat slegs aan een<br />

meisie en een seun toegeken is) en ‘n beurs om die sewende sessie, ‘n ekstra week, by te woon.<br />

0 Suid-Afrikaanse Musiek Onderwyser |<strong>144</strong> | November <strong>2006</strong>

From 18 to 22 September this year the Tygerberg centre<br />

of the SASMT successfully presented the eighteenth<br />

Sanlam National Music Competition in the marvellous<br />

auditorium of the Hugo Lambrechts Music Centre in<br />

Parow, Cape Town. Over the past two decades this event<br />

has become an important, permanent feature of the<br />

South African cultural landscape.<br />

The overall winner this year was the thirteen year old<br />

saxophonist, Hamman Schoonwinkel, who delivered an<br />

impassioned recital programme, maturely conceived<br />

and executed. He was ably supported by the emotionally<br />

charged piano playing of Phillipus Hugo. Hamman’s<br />

programme comprised a complex set of pieces, and<br />

included a masterful interpretation of Pequeña C<strong>za</strong>rda<br />

by Ilturralde. Selmari du Toit (also thirteen years<br />

old), a pianist who was participating for the seventh<br />

consecutive year, was awarded the second prize. Her<br />

performance of numerous advanced compositions<br />

included the demanding third movement from Ravel’s<br />

Sonatina. Selmari’s playing was marked by clarity and<br />

precision, transparent textures and stylistic awareness<br />

throughout the competition. Christina Brabetz, twelve<br />

years old and a violinist, was awarded the third prize.<br />

A strong, dashing player, Christina rendered works by<br />

Wieniaswki and Paganini-Kreisler like a virtuoso. This<br />

exciting tour de force was given substantial backing<br />

by Tersia Downie, who officiated at the piano. Jason<br />

Mayr (twelve) was awarded a category prize for ‘other<br />

instruments’ for his recorder playing.<br />

The identification and fostering of exceptional learners<br />

during their primary school years is one of the aims stated<br />

by the founder of this competition — Prof Hubert van<br />

der Spuy. The success of participants after the competition<br />

is proof that this aim is achieved. The competition<br />

provides a unique and rewarding learning experience<br />

for each participant, and an atmosphere of supportive<br />

camaraderie exists between the participants, their parents<br />

and teachers. A ‘family spirit’ is experienced during<br />

the competition week, and fostered in and outside<br />

the performance venue. Marie Gaerdes’s observation in<br />

her presidential address (SAMT, May <strong>2006</strong>: 26) that “the<br />

healthy music education of the very young child [is one<br />

aspect, whilst] on the other hand [there are] competitions”<br />

suggests a polarisation of the two activities. The<br />

positive and amicable climate which has been guarded<br />

at the Sanlam competition since its inception and the<br />

results of the competition show that Gaerdes’s observation<br />

is not necessarily universally true.<br />

To progress from the Sanlam competition to the ABSA<br />

competition (for high school learners) has become a<br />

natural path for most Sanlam participants. For example,<br />

in 2004 nineteen of the forty participants in the<br />

ABSA competition had previously ‘cut their teeth’ in the<br />

South African Music Teacher |<strong>144</strong> | November <strong>2006</strong><br />

The Sanlam National Music Competition <strong>2006</strong><br />

Sanlam competition. The fruits of the Sanlam competition<br />

are evident when the ever-increasing tender age of<br />

prize-winners at the ABSA Competition is considered.<br />

This year Reabetswe Thipe (2004 overall winner of the<br />

Sanlam competition) and Michael Duffet (a participant<br />

in the 2003 and 2004 Sanlam competitions) won joint<br />

first prize at the ABSA competition. Both winners are fifteen<br />

years of age and perform with consummate skill.<br />

Numerous entrants in the ABSA competition frequently<br />

continue to develop their performance careers in early<br />

adulthood through participating in the ATKV national<br />

competition as well as through appearances with professional<br />

orchestras. In 2004 seven out of twenty-eight<br />

finalists in the ATKV competition were former Sanlam<br />

participants. All this clearly displays the musical and<br />

educational value of the Sanlam competition.<br />

A further dimension of the Sanlam competition is the<br />

promotion of South African compositions. This is due, to<br />

a certain extent, to the existence of a prize for the best<br />

performance of a South African composition during the<br />

competition. During this year’s competition the works of<br />

thirteen South African composers were showcased with<br />

Peter Klatzow and Hubert du Plessis each represented<br />

by two works. In previous competitions the Cape Town<br />

composer Dimtri Roussopoulos was commissioned to<br />

write works which were premiered by participants at the<br />

competition, such as The Edge of Eternity (2003) for flute<br />

and Song of the Old Buccaneer (2004) for saxophone. The<br />

trend was unfortunately not continued this year. It is,<br />

in my opinion, an important aspect of the competition<br />

which ought to be endorsed and expanded by participants<br />

and their teachers, since the competition strives<br />

to inculcate both the creative and performance aspects<br />

of South African classical music.<br />

A successful innovation at this year’s competition was<br />

the inclusion of a short recital performed by the 1991<br />

winner, guitarist James Grace. This is a feature which<br />

the <strong>org</strong>anising committee could successfully develop<br />

in future competitions. The opening programme on<br />

Monday, 18 September, highlighted the talent of the<br />

2005 winner, Jacqueline Wedderburn-Maxwell. She performed<br />

with musical insight the Bruch Violin Concerto,<br />

and was supported by the Hugo Lambrechts Symphony<br />

Orchestra under the direction of Leon Hartshorne. The<br />

appearance of both Wedderburn-Maxwell and Grace<br />

during the competition displays the interest of the <strong>org</strong>anisers<br />

in building upon the foundations of the competition<br />

and in f<strong>org</strong>ing a festive atmosphere during the<br />

week of the competition.<br />

This landmark event has evolved into a celebration of<br />

South African talent and deserves the support of all<br />

who encourage our young and growing musicians.<br />

Dr Jeffrey Brukman

Michael Whiteman, musician, mathematician and mystic,<br />

completed a lifespan of one hundred years on 2 November<br />

<strong>2006</strong>. And he still is very much up and about!<br />

Those who know him are incredulous of the idea that he<br />

has, in fact, aged in years. Admittedly, his body has not<br />

been able to escape all attendant symptoms of aging<br />

(his knees are a bit ‘wobbly’ and he had to sell his car!),<br />

but his indefatigable mind and spirit are as agile as ever.<br />

Always active, they are constantly weighing up new<br />

ideas against handed down traditional beliefs, probing<br />

with relentless logic and dissecting with the sharp edge<br />

of a scalpel. That is Michael, the mathematician and<br />

scientist.<br />

Michael the mystic is another side of this great mind,<br />

developing profound strands of thought on mysticism,<br />

comparative religion, philosophy of science, parapsychology<br />

and psychopathology — writing and publishing<br />

widely. His next book is due to be published<br />

in time for his hundredth birthday celebrations.<br />

When thinking of Michael the musician, what first<br />

comes to mind is his unselfish dedication to the<br />

South African Society of Music Teachers through<br />

more than five decades. (I partly quote from my<br />

presidential address in March 1991 at the Stellenbosch<br />

conference, when Prof Whiteman’s 50<br />

years as editor of our society’s journal were celebrated;<br />

published in The South African Music<br />

Teacher, vol 118, June 1991.) He became editor of<br />

this journal in July 1941 (No. 20) and continued<br />

compiling, editing and seeing through publication,<br />

each and every issue of the journal until No.<br />

127 in December 1995. Apart from this he has<br />

been President (1948, 1957 and 1962), Vice-President<br />

Western Cape (1950, 1952-1956), member<br />

of council for at least 50 years; also member of<br />

many executive committees, for many years trustee<br />

of the SASMT Benevolent Fund, also for many<br />

years representative of the SASMT on the CAPAB<br />

Music Committee, our anchor and adviser in constitutional<br />

and other matters of the SASMT and<br />

— how else could it be? — an outstanding music<br />

teacher in his own right. He regularly held licentiate<br />

classes for piano teaching method and paper<br />

work and prepared piano students for their practical<br />

examination, resulting in about 65 diploma<br />

successes.<br />

A major contribution to the structure of the<br />

SASMT was his reworking of the constitution in<br />

Prof Michael Whiteman on his 100th birthday<br />

Reino Ottermann<br />

order to also include institutional membership for universities<br />

and other centres of music education. Those<br />

of us who have been more closely associated with the<br />

SASMT remember him as the indefatigable defender of<br />

the constitution of the SASMT, sometimes to the irritation<br />

of less informed conference members, but many<br />

times saving us embarrassment vis-à-vis our own constitution<br />

or, even worse, being caught off-side to our<br />

own detriment. No wonder that honorary membership<br />

of the SASMT was conferred on him in 1971.<br />

Michael Whiteman was born on Tulse Hill, London, on 2<br />

November 1906. He was educated at Highgate School<br />

and at Caius College in Cambridge. After some time in<br />

his father’s publishing business and a number of years<br />

as scholastic head of Stafford’s School in Harrow Weald<br />

he and his wife, Sona, came to South Africa in January<br />

1937 where he accepted a position at the Diocesan<br />

Suid-Afrikaanse Musiek Onderwyser |<strong>144</strong> | November <strong>2006</strong>

College in Rondebosch. In 1939 he joined the University<br />

of Cape Town’s staff, lecturing pure mathematics and,<br />

later, applied mathematics. In 1943 he was awarded a<br />

doctorate for research into the philosophical foundations<br />

of mathematics. And then, also in 1943, he became<br />

lecturer in music at Rhodes University College in<br />

Grahamstown! His eminent suitability for this post is<br />

best proven by a quotation from the South African Music<br />

Encyclopedia (vol. 4, 1986) in which his development as<br />

a musician is outlined:<br />

His piano lessons had started in 1913 and later<br />

were continued with his future wife Sona at Stafford’s<br />

School. In 1938 he obtained the L. Mus. TCL<br />

in composition and then consecutively the FTCL<br />

(1940), the B. Mus. of UNISA (1943), and an M. Mus.<br />

of the University of Cape Town (1947). From 1937<br />

to about 1942 he devoted himself to the French<br />

horn and to conducting (under the supervision of<br />

Professor Stewart Deas). In Cape Town he acted for<br />

many years as an additional horn player in the city<br />

orchestra and as the originator and conductor of<br />

a small orchestra which performed at ballet performances<br />

produced by Dulcie Howes and at Rose<br />

Ehrlich’s Shakespearean Productions. Between<br />

1940 and 1942 he also applied himself to learning<br />

the cello and eventually participated in chamber<br />

music performances.<br />

In Grahamstown he lectured, played chamber music<br />

and two piano works, conducted a madrigal choir and<br />

occupied himself with composition. But he returned to<br />

the Department of Applied Mathematics at Cape Town<br />

University in 1946 where he finally became Associate<br />

Professor. What a fascinating life story!<br />

When I think of Michael Whiteman, loyalty, reliability<br />

and integrity, absolute dedication, sincerity and modesty,<br />

and a wonderful sense of humour are some of the<br />

most outstanding characteristics that come to mind. All<br />

this is not only supported, but also, as it were, transilluminated<br />

by the profound spirituality which I so deeply<br />

admire in him. We are indeed fortunate to have a man<br />

like him who has through all these years not only shown<br />

but also lived an unconditional involvement in the weal<br />

and woe of our society.<br />

Prof Michael Whiteman became involved in the affairs<br />

of the SASMT at the beginning of 1941. And now, after<br />

65 years and after a lifespan of a whole century, he still<br />

has the affairs of the society at heart — albeit somewhat<br />

detached, leaving space for all the other interests which<br />

have made the life of this remarkable musician, mathematician<br />

and mystic so unique.<br />

We congratulate him on this extraordinary birthday and<br />

thank him for everything he has done for our society.<br />

May the following years be as rewarding and brimful of<br />

the marvellous thoughts and ideas that have been the<br />

distinctive features of a life richly and humbly lived.<br />

South African Music Teacher |<strong>144</strong> | November <strong>2006</strong><br />

South African Auditions for<br />

The World (Youth) Orchestra<br />

International tours in Canada<br />

and Europe<br />

The World Orchestra of Jeunesses<br />

Musicales International (WOJM) is<br />

preparing its annual auditions for the<br />

2007/08 season. South African musicians<br />

and musicians of all nationalities wanting<br />

to become members of this wonderful<br />

project can apply for auditions online<br />

on www.lmwo.<strong>org</strong> before the 15th of<br />

November <strong>2006</strong>. Candidates must be<br />

aged between 18 and 28, and auditions<br />

will be <strong>org</strong>anised in each country by<br />

national sections of Jeunesses Musicales<br />

– in South Africa by Jeunesses Musicales<br />

South Africa, based at the Potchefstroom<br />

campus of the North-West University,<br />

step one being applying online.<br />

Since WOJM moved its headquarters to<br />

Valencia (Spain), it has toured China,<br />

the Netherlands, Austria, Spain and<br />

Cyprus. New members will join The<br />

World Orchestra for the next season to<br />

travel in Canada and Europe.<br />

As UNESCO Artist for Peace, The World<br />

Orchestra is committed to peace,<br />

interculturality, solidarity and cooperation<br />

between cultures. Formed by a hundred<br />

musicians from forty countries and<br />

conducted by Maestro Josep Vicent,<br />

WOJM tries to communicate its message<br />

all over the world.<br />

The new WOJM focuses on contemporary<br />

classical music of the 20th and 21st<br />

centuries and encourages interactions<br />

between other musical forms and<br />

traditions such as ethnic, jazz or<br />

contemporary non-classical music. The<br />

repertoire always includes new pieces<br />

specially written for the orchestra.<br />

www.jmwo.<strong>org</strong><br />

Department of Culture, NWU, Potchefstroom,<br />

2520. Tel (018) 2992844, Fax.<br />

(018) 29928942.

A s s e s s i n g P r o g r e s s i n M u s i c<br />

T h o r o u g h r e s e a r c h o n t h e a s s e s s m e n t o f<br />

m u s i c p e r f o r m a n c e s , r e v e a l s u n e x p e c t e d<br />

i n s i g h t s . F a r f r o m b e i n g i m p e n e t r a b l e<br />

a n d u n r e l i a b l e , i t m a y b e a p a r a d i g m f o r<br />

s u m m a t i v e a s s e s s m e n t i n o t h e r s u b j e c t s .<br />

Much has been written on assessment in music. For example,<br />

the US publication Assessing the Developing Child<br />

Musician by Tim Brophy (2000), runs to almost 500 pages.<br />

I do not intend to duplicate all that effort here, but to make<br />

some observations about what it might mean to assess<br />

progress in music musically.<br />

The system for assessing music in the national curriculum<br />

for music in England is ‘holistic’ rather than ‘segmented’.<br />

Instead of giving students marks (perhaps out of ten) for<br />

many different aspects of music, and adding them all up to<br />

give a total mark that tells you how good a student is (segmented<br />

assessment), teachers are expected to consider a<br />

student ‘in the round’ (what I would call holistically), and<br />

to consider which of the published ‘level descriptions’ they<br />

match most closely. While I have already questioned some<br />

of the content of the published level descriptions, 1 I think<br />

that this is a musical approach to assessment.<br />

Let us take the example of performance in music. As I<br />

leave a concert, I have a clear notion of the quality of the<br />

performance that I have just heard. If someone asks me to<br />

justify my view, I may start to talk about rhythmic drive,<br />

or interpretation, or sense of ensemble, for example. But I<br />

move from the whole performance to its components. I do<br />

not move from the components to the whole. In particular,<br />

I do not think: the notes were right, the rhythm was<br />

right, the phrasing was coherent, and so on – therefore I<br />

must have enjoyed this performance. And I certainly do<br />

not think something such as:<br />

SKILLS + INTERPRETATION = PERFORMANCE<br />

I recall performances that have overwhelmed me, despite<br />

there being a handful of wrong notes. I remember others<br />

in which the notes have been accurate, and the interpretation<br />

has been legitimate, and yet the overall effect has been<br />

sterile. A performance is much more than a sum of skills<br />

and interpretation.<br />

Segmented marking systems are used routinely in some<br />

other subjects, and may be appropriate in some fields of<br />

music. For example, teachers assessing students’ recall of<br />

Janet Mills<br />

factual information about music, or success in solving a<br />

mathematical problem, typically use such schemes. The<br />

point is that the assessment needs to fit the behaviour being<br />

assessed. A musical performance is not a mathematical<br />

problem.<br />

Mathematical problems are sometimes set to provide a<br />

context for the assessment of qualities such as aspects of<br />

mathematical thought. Here, it makes sense to use a segmented<br />

marking scheme that will tease out the aspects to<br />

be assessed, and to ask students to present their solutions<br />

so that they can be given a mark for each of the aspects<br />

that they have grasped. Otherwise, a student who has been<br />

through the intended thought processes, but has produced<br />

no evidence of this, and who perhaps gives an incorrect<br />

answer because of some trivial computational error at<br />

the end, for example, will not receive appropriate credit.<br />

Musical performances are not like this. There is no need<br />

for musical performance to be set in a context: it provides<br />

its own. The musical performance assessor is fortunate in<br />

being presented with the actual behaviour that he or she<br />

is to assess. It makes no sense to dissect the performance,<br />

give a mark for each of the bits, and then reassemble them<br />

by adding up the marks.<br />

One sometimes hears teachers arguing for segmented assessment<br />

on the grounds that holistic assessment is ‘subjective’.<br />

Of course, all assessment is subjective, in the sense<br />

that human beings determine how it is done. Even the<br />

most detailed mark scheme for a mathematics problem<br />

— perhaps one that justifies exactly what a student has to<br />

write in order to gain each mark — is subjective because<br />

it was designed by a human being. Other human beings<br />

might have set a different problem, or structured the mark<br />

scheme in some other way. That assessment is subjective,<br />

in the sense that human beings are involved in it, is surely<br />

something to be celebrated rather than bewailed. The material<br />

being assessed is, after all, human endeavour.<br />

Subjectively, then, I would argue is not necessarily a problem.<br />

But what of reliability? Are students who are assessed<br />

holistically more likely to be given differing marks by<br />

Suid-Afrikaanse Musiek Onderwyser |<strong>144</strong> | November <strong>2006</strong>

different assessors than students who are assessed using a<br />

segmented scheme? Not necessarily. Holistic assessment<br />

is not totally reliable, in the sense that all assessors will<br />

always come to complete agreement. On the other hand,<br />

neither is segmented assessment totally reliable. It is not<br />

clear why marks for components of performance, such as<br />

rhythm, should be any more reliable than marks for performance<br />

itself, and a segmented marking scheme simply<br />

combines a series of marks for such components. In fact,<br />

Harold Fiske, 2 working in Canada, reported an experiment<br />

in which holistic assessment was found to be more reliable<br />

than segmented assessment. Fiske collected cassette<br />

recordings of a series of trumpet performances, and asked<br />

music students to assess them on five scales used in local<br />

music festivals: overall, intonation, rhythm, technique,<br />

and interpretation. He found greater interjudge reliability<br />

for the overall grade than for any of the segmented grades.<br />

In other words, there was much less agreement about ratings<br />

for intonation, rhythm, technique, and interpretation<br />

than there was for overall ratings. Why should this be? I<br />

would suggest two reasons:<br />

1.<br />

2.<br />

Overall performance is real. In other words, all<br />

the judges hear the same performance. If we are<br />

to assess a component of the performance, such<br />

as rhythm, on the other hand, we must filter out<br />

much of the other material. Our ability to do this,<br />

or our technique of doing this, will vary. Thus our<br />

perceptions of the rhythmic element of a performance<br />

may differ. Abstracting rhythm from melody<br />

is not a conceptually simple matter like filtering out<br />

impurities from a sample of rain water, or absorbing<br />

light rays within some defined frequency range:<br />

melody consists of a dynamic relationship between<br />

rhythm, pitch, and a host of other variables. Indeed,<br />

it is not clear what the expression ‘the rhythm of a<br />

performance’ really means.<br />

We are practised in the assessment of overall performance.<br />

Every time we listen to a TV theme tune,<br />

a pop song, a Mahler symphony, or the ringing of<br />

mobile phone, we have the opportunity to make<br />

judgements about what we hear. On the other hand,<br />

we are less frequently presented with examples of<br />

pure rhythm or intonation, whatever either of these<br />

mean, to assess.<br />

It might be possible to train assessors to become more<br />

reliable in segmented assessment. But why should one<br />

bother to do this? If holistic assessment is already more<br />

reliable, surely it makes sense to use training in an attempt<br />

to strengthen it further?<br />

Holistic assessment is sometimes criticized on the grounds<br />

that assessment is credible only if it is possible for an assessor<br />

to verbalize exactly what they are doing. Musical<br />

performance is an essentially nonverbal activity, and its<br />

reduction to a verbal common denominator seems of uncertain<br />

value. Yet there are elements of holistic assessment<br />

that can be verbalized, as an experiment that I carried out<br />

some years ago illustrates. 3<br />

South African Music Teacher |<strong>144</strong> | November <strong>2006</strong><br />

I started by arguing that, as holistic assessment has some<br />

inter-judge reliability, it is reasonable to suppose that there<br />

are common aspects to individuals’ holistic assessments.<br />

However, we do not know what these common aspects<br />

are: the experiment was intended to find them.<br />

The theoretical background to the experiment was drawn<br />

from personal construct theory (PCT). 4 Ge<strong>org</strong>e Kelly, a<br />

psychotherapist, believed that a person sees other people<br />

through a personal system of constructs. A psychotherapist<br />

who knows a client’s construct system has a basis for<br />

planning, and then starting, therapy. But clients typically<br />

cannot explain their construct system to the psychotherapist:<br />

it has to be elicited. Consequently, Kelly developed a<br />

technique that he called triangulation: a client is presented<br />

with the names of three people he or she knows, and asked<br />

to state a way in which two are the same and the other is<br />

different. The extent to which the factor suggested is one<br />

of the client’s constructs is then explored.<br />

In my experiment, I looked for the constructs that might<br />

be used as a framework for holistic assessment of performance<br />

in music. Again, they were hidden. But a substantial<br />

difference from Kelly’s situation was that I hoped to find<br />

a universal, not personal, system. However, triangulation<br />

again proved a useful technique.<br />

Initially, I made a videotape of five solo musical performances,<br />

each on a different instrument. All the performers<br />

were judged by their teachers to be of at least Grade 8<br />

standard, and were of similar age (15-19). Eleven student<br />

teachers with widely differing musical experience watched<br />

and ranked the five video performances, and then I interviewed<br />

each of them individually. I chose three performances,<br />

and asked students to describe a characteristic that<br />

two performances had, but the other lacked. I then asked<br />

students to tell me whether the remaining two performances<br />

had, or lacked, this characteristic. By repeating the<br />

exercise with different groups of three performances, I<br />

established what was, I hoped, some of the individual’s<br />

constructs. I then pooled the supposed constructs of the<br />

eleven individuals, obtaining the following list:<br />

C1 The performer was CONFIDENT/NERVOUS<br />

C2 The performer DID ENJOY/ DID NOT ENJOY playing<br />

C3 The performer WAS FAMILIAR WITH/HARDLY KNEW<br />

the piece<br />

C4 The performer MADE SENSE/DID NOT MAKE SENSE of<br />

the piece as a whole<br />

C5 The performer’s use of dynamics was APPROPRIATE/<br />

INAPPROPRIATE<br />

C6 The performer’s use of tempi was APPROPRIATE/<br />

INAPPROPRIATE<br />

C7 The performer’s use of phrasing was APPROPRIATE/<br />

INAPPROPRIATE<br />

C8 The performer’s technical problems were HARDLY<br />

NOTICEABLE/DISTRACTING<br />

C9 The performance was FLUENT/HESITANT<br />

C10 The performance was SENSITIVE/INSENSITIVE<br />

C11 The performance was CLEAN/MUDDY<br />

C12 I found this performance INTERESTING/DULL

The next stage was to see what happened when another<br />

29 assessors were asked to use C1-C12 to judge performances.<br />

This time, the video recording consisted of a series<br />

of ten solo performances, each on a different instrument.<br />

There were two groups of assessors:<br />

Group 1: Twelve music teachers and student teachers<br />

specializing in music<br />

Group 2: Seventeen student teachers specializing in subjects<br />

other than music<br />

Some members of this group had shown interest in<br />

music through, for example, joining their college<br />

choir. But none had studied music at school beyond<br />

the age of 16, or taken instrumental lessons since<br />

leaving school.<br />

The assessors were asked to imagine that each performance<br />

was part of a Grade 8 examination, and to assess the<br />

performance as seen and heard without making any allowances,<br />

for example for performers who looked younger.<br />

For each performance there was a double-sided sheet to<br />

be completed. On the first side, the assessor gave a single<br />

mark of up to 30 using the Associated Board of the Royal<br />

Schools of Music’s criterion-referenced classification system<br />

(distinction, merit, pass, and fail) as a guide. On the<br />

second side, the assessor rated the performance on each of<br />

the twelve bipolar constructs using a four-point scale.<br />

The marks given by individuals for performances were converted<br />

into ranks, with the performance given the highest<br />

mark being assigned a rank of one. The constructs were<br />

scored from one to four according to their placing on the<br />

four-point scale. There was a positive correlation between<br />

each of the constructs and the overall rank ranging from r<br />

= 0.4 (C6) to r = 0.7 (C10 and C11) (n = 290). 5 I followed<br />

this up with another statistical technique: multiple regression<br />

analysis. 6 This showed that the constructs accounted<br />

for more than two-thirds of the variance in the ranking<br />

of the performances, for both Group 1 and Group 2. This<br />

indicates that the holistic assessment could be accounted<br />

for in terms of common constructs to a substantial extent.<br />

It is interesting that there is so little difference in the results<br />

for Groups 1 and 2, i.e. that there is little apparent difference<br />

in the holistic assessment according to the extent of<br />

formal musical expertise. This offers tentative support to<br />

the theory that the reliability of holistic assessment stems,<br />

at least partly, from practice in every situation.<br />

We have seen that holistic assessment has advantages over<br />

segmented assessment. It is more musically credible, in<br />

the sense that it is more like assessment made of musical<br />

performance in the real world. In addition, it can be more<br />

reliable, and no more subjective.<br />

This discussion has been possible only because there is<br />

some general understanding of what is meant by ‘performer’<br />

and ‘performance’. We have some idea of what assessment<br />

systems in this field are trying to predict. We can<br />

tell if the marks produced are nonsense.<br />

This is an unusual situation. Much educational assessment<br />

with an outcome of a single mark or grade takes place in<br />

a less certain context. We may know what a performer is,<br />

but do we know what a musician is? Yet we routinely combine<br />

marks obtained for listening, composing, and performing<br />

to give a music GCSE, or A level grade. Is there an<br />

understanding of what a mathematician or a scientist is?<br />

Yet we combine marks to give single grades also in these<br />

subjects.<br />

It is sometimes argued that there is something particularly<br />

difficult about assessment in the arts. Might it not be that<br />

some areas of the arts offer opportunities for particularly<br />

rigorous assessment? If we understand what behaviour<br />

we are trying to measure, then we can tell if the marks<br />

we obtain are sensible. Perhaps those who devise summative<br />

assessment systems for non-arts subjects could learn<br />

something from looking at aspects of the arts.<br />

BIBLIOGRAPHY AND FURTHER READING<br />

FISKE, M. 1977. Relationship of Selected Factors in Trumpet<br />

Performance Adjudication Reliability. Journal of<br />

Research in Music Education. 25(4):256-263<br />

KELLY, G. 1955. The Psychology of Personal Constructs.<br />

New York: Norton.<br />

MILLS, J. 1991. Assessing Musical Performance Musically.<br />

Educational Studies. 17(2):173-181.<br />

MILLS, J. 2005. Music in the School. Oxford: Oxford University<br />

Press.<br />

Reproduced from Music in the School by permission of<br />

Oxford University Press (www.oup.com).<br />

ISBN 0-19-322300-7<br />

Janet Mills is a Research Fellow at the Royal College of Music, London.<br />

She began her career as a secondary school music teacher,<br />

and was a teacher trainer prior to working for<br />

ten years as an HM inspector of Schools. She<br />

works widely in schools, universities and the<br />

community. Her writing includes Music in the<br />

School (OUP 2005), Music in the Primary School<br />

(CUP 2001) and many research articles.<br />

1.<br />

2.<br />

3.<br />

4.<br />

5.<br />

6.<br />

See Mills 2005:156<br />

Fiske 1977<br />

Mills 1991<br />

Kelly 1955<br />

Correlation coefficients (denoted r) can range from 1 (perfect<br />

positive correlation) to 0 (no correlation) to -1 (perfect negative<br />

correlation). So the marks that assessors gave the performance<br />

were influenced most by whether the performance was<br />

clean or sensitive, and least by whether they thought that the<br />

tempo was appropriate.<br />

The multiple regression analysis searched for values a1 to a12<br />

such that a ‘regression’ equation of the form:<br />

Rank = a1C1 + a2C2 +a3C3 + … + a12C12<br />

accounts for as much as possible of the variance in ranks, when<br />

calculated across the 29 x 10 = 290 performances heard. The<br />

regression equation that was calculated here accounts for<br />

71% (n = 290) of the variance in the ranks. The separate figures<br />

for Groups 1 and 2 are 73% (n = 120) and 69% (n = 170)<br />

respectively.<br />

Suid-Afrikaanse Musiek Onderwyser |<strong>144</strong> | November <strong>2006</strong>

D i s t e v e r o m t e r y . . .<br />

I t w a s t o o f a r t o d r i v e . . . W i t h t h e n e a r e s t e x a m i n a t i o n<br />

c e n t r e s i x h o u r s ’ a w a y , t h i s m u s i c t e a c h e r d e c i d e d t o<br />

e s t a b l i s h o n e i n h e r h o m e t o w n .<br />

When we moved to the United States in January 1999, I<br />

knew that my life would change dramatically. I had always<br />

been a ‘career woman’, working full-time through my pregnancies<br />

and while bringing up two boys. Now, because of<br />

visa restrictions I would not be allowed to earn an income<br />

in our new country of residence. I decided to throw myself<br />

into being a ‘lady of leisure’, which meant running a<br />

household, driving two teenage boys and their friends to<br />

and fro, and getting involved in volunteer work. After four<br />

years of this, I felt I needed something new in my life. The<br />

dream of returning to piano, which I had always pushed<br />

away far into the distant future, finally became a reality<br />

when I signed up for lessons with Olga Jaynes at Burt Music<br />

School, in Cary, my new hometown in North Carolina.<br />

In the fall of 2003 I also signed up for theory lessons with<br />

Tom Lohr at the School of Music at Meredith College for<br />

Women, a local private university, in Raleigh, our capital<br />

and neighboring city. Olga, originally from Ukraine, and<br />

a recent transplant like me, inspired me with her love for<br />

the piano and her dedication to her students. Tom at the<br />

same time opened up a whole new world for me with his<br />

knowledge of music theory and his amazing ability to convey<br />

all this knowledge in a concrete way to a student. I was<br />

hooked, and knew that from now on piano would be a major<br />

part of my life, as it had been when I was growing up.<br />

Coming from South Africa, I knew about the music examination<br />

system of the University of South Africa<br />

(UNISA) as well as those of the Associated Board of the<br />

South African Music Teacher |<strong>144</strong> | November <strong>2006</strong><br />

Marietjie Wessels<br />

Royal Schools of Music (ABRSM), and similar systems in<br />

other countries. I was keen to find a corresponding system<br />

in the United States, and work to get up to at least Grade<br />

8 level. To my surprise, I couldn’t find anything similar<br />

in the United States. The closest I could get was the program<br />

of the National Guild of Piano Teachers that offers<br />

18 different levels of adjudication, in six different categories,<br />

but with no prescribed lists of repertoire to choose<br />

from (only guidelines). The Guild system did not seem to<br />

set any national standard for music teaching and learning,<br />

and my music teachers were not participating members of<br />

the Guild at the time, so I abandoned the idea of enrolling<br />

in their program.<br />

In September of 2003 we received our permanent residence<br />

permits (‘green cards’), and I was now allowed to<br />

work in the United States, something my husband had<br />

been looking forward to! There was no way I was going<br />

to give up my piano and music lessons, so I had to make<br />

a plan. A friend suggested that I become a piano teacher.<br />

I balked at the idea initially because I felt I had not been<br />

trained as a music teacher. However, both Olga and Tom<br />

encouraged me to do that, and suggested that I join the<br />

local piano teachers’ associations. In the summer of 2004<br />

I joined both the Cary-Apex Piano Teachers’ Association<br />

(CAPTA — 53 members) and the Raleigh Piano Teachers’<br />

Association (RPTA — 140 members), and slowly became<br />

involved in the world of piano teaching.

In January 2005 I noticed in a RPTA newsletter that RACE<br />

was looking for a center representative in North Carolina.<br />

When I made further enquiries I found out that RACE was<br />

the acronym for Royal American Conservatory Examinations,<br />

which had just been established in the summer of<br />

2004. When I logged on to their website (http://www.royalamericanconservatory.<strong>org</strong>),<br />

I became really excited. This<br />

was just what I had been looking for!<br />

RACE offers a Certificate Program in collaboration with<br />

The Royal Conservatory of Music, founded in Canada<br />

in 1886. As is the case with the UNISA exams in South<br />

Africa, students are assessed in the practical areas of repertoire,<br />

technique, ear training and sight reading, while<br />

there are separate theoretical examinations in rudiments,<br />

harmony, keyboard harmony, counterpoint, analysis and<br />

music history. Unlike the UNISA system, the levels in<br />

both the RCM and RACE systems range from Grade 1 to<br />

Grade 10, with the top certificates being the Performer’s<br />

and the Teacher’s ARCT (Associate of the Royal Conservatory<br />

of Toronto). In addition, RACE offers two pre-grade<br />

levels, namely, Preparatory A and Preparatory B, roughly<br />

corresponding to one and two years of piano study respectively.<br />

In order to receive their Preparatory Level Certificate,<br />

students need to do both the A and B levels practical<br />

examinations, and write a Preparatory Theory paper.<br />

Another difference between RACE/RCM and the UNISA<br />

system is that the former offers the student a much bigger<br />

choice of repertoire in each list. For instance, in Grade 8,<br />

the number of works ranges from 21 in List B (Classical<br />

and Classical-style) to 56 in list D (20th century).<br />

What I found particularly appealing about RACE is that<br />

their certificate program offers a national standard, based<br />

on an internationally recognized system that is more than<br />

a hundred years old. (More than 17,000 teachers and<br />

100,000 students are involved in the RCM/RACE program<br />

every year, the majority of them being from Canada at this<br />

stage.) I knew that I had found the program I wanted to<br />

do, but was not sure whether I was ready to take on the<br />

task of becoming a RACE center representative, since that<br />

would take time away from my own music studies. (By<br />

this time I had switched to Tom Lohr for piano instruction<br />

and was also taking music courses (for non-degree<br />

purposes) in the Department of Music at Meredith College.)<br />

However, when I saw that the closest RACE center<br />

was about six hours’ drive from Cary, in the neighboring<br />

state of Virginia, I started toying with the idea of getting<br />

a center started in our area. I contacted the president of<br />

RPTA, Kathy Sparks, who informed me that no one had<br />

responded to the invitation yet.<br />

To cut a long story short, in the summer of 2005 I signed<br />

the contract to become the first RACE center representative<br />

in North Carolina, with my home studio being the<br />

center for the time being. Kathy Sparks was very enthusiastic,<br />

and recommended to the Board of RPTA that they<br />

invite Dr Scott McBride Smith, president<br />

of RACE, to come and do a workshop on<br />

RACE at the November RPTA meeting.<br />

The workshop was open to all interested piano teachers,<br />

parents and students in the area, and was attended by<br />

about one hundred people. It was a great success. For close<br />

to two hours Dr Smith kept the audience informed and<br />

entertained with background on the state of music teaching<br />

in the USA, and the objective of RACE to provide a<br />

national standard. A point he stressed is that RACE uses<br />

RACE encourages students to register online, to<br />

speed up the process and cut out unnecessary paper<br />

work for the RCM staff in Toronto, who do the<br />

administration. Teachers are also encouraged to<br />

register with RACE and obtain a Teacher Number.<br />

When students register online, they get the opportunity<br />

to enter their teacher’s number, which gives<br />

the teacher access to the students’ examination<br />

information on the RACE web site, via the Teacher<br />

Services link. When students register the first time,<br />

they receive a Candidate Identification Number<br />

which they keep for as long as they take part in the<br />

RACE program. They also receive a confirmation<br />

number and get the opportunity to print out an Examination<br />

Appointment Confirmation form, as well<br />

as a Piano Examination Schedule. The latter form<br />

includes all the student’s particulars, the scheduled<br />

time of the practical examination, and the Piano<br />

Examination Program. Students are required to indicate<br />

on the Examination Program whether they<br />

prefer to start with the repertoire or the technical<br />

requirements during the examination. They also<br />

need to list all pieces played in the order in which<br />

they will be played for the judge.<br />

On the day of the examinations candidates need<br />

to bring both forms with them to the examination<br />

center. The center representative checks the first<br />

one against her/his list of registered candidates, and<br />

checks that the second one is completed correctly<br />

before the candidate hands it to the examiner.<br />

examiners who are trained to be as objective as possible<br />

and assess performance according to a uniform standard.<br />

Examiners are also constantly monitored to ensure that<br />

they ‘stick to the standard’ and provide useful, informative<br />

comments on the evaluation forms. After the workshop I<br />

was approached by Janet Mahoney, a fellow CAPTA member,<br />

who offered her brand new business, Village Music<br />

School, Inc. in Carpenter Village subdivision in Cary as a<br />

possible center for RACE. (A subdivision is almost like a<br />

gated community development in South Africa, but without<br />

the gates.) When I visited Village Music School, Inc.<br />

and saw the lovely facilities I knew that I had found the<br />

ideal venue. So, in December 2005, Village Music School,<br />

Inc. officially became the first RACE center in North<br />

Carolina.<br />

Suid-Afrikaanse Musiek Onderwyser |<strong>144</strong> | November <strong>2006</strong>

In the meantime I had received the facility booking forms<br />

(electronically) from Robin Virzi, the very efficient RACE<br />

Center Coordinator in Dayton, Ohio, which required me<br />

to estimate the number of students who would take part<br />

in the practical and theory examinations in May <strong>2006</strong>.<br />

(RACE offers examination sessions twice a year, in December<br />

and in May, but because ours was a new center,<br />

we had to wait for the May session.) Since examiners are<br />

sent from Canada for the practical examinations, I also<br />

had to provide names and addresses of suitable hotels on<br />

the booking forms.<br />

By then I had put together an email list of interested teachers,<br />

who sent me their estimates for the examinations. It<br />

seemed that there would be around 20 students doing the<br />

practical and two doing theory examinations. On 10 January<br />

<strong>2006</strong> Robin informed all center representatives that<br />

online registrations had opened, with the due date set as<br />

27 February (which was eventually extended to 6 March).<br />

In April I received the paperwork for the theory and practical<br />

examinations via courier from Toronto. It turned out<br />

that two students had registered for the theory examinations<br />

as expected, while 23 students had registered for the<br />

practical examinations, covering a range from Preparatory<br />

A to Grade 7. The RACE/RCM theory examinations have<br />

a fixed timetable, with examinations taking place on the<br />

Friday afternoon and the Saturday morning of the second<br />

weekend in December, May and August respectively. So,<br />

on Saturday, 13 May, I supervised (or proctored, as they<br />

say over here) the two theory candidates, aged 6 and 8.<br />

The experience brought back memories of my own childhood,<br />

and the writing of similar exams decades before in<br />

South Africa. I thought about how much had happened<br />

in my life since then. When I wrote my theory papers in<br />

the early seventies, who would ever have dreamt that more<br />

than 30 years later, I would be supervising two students in<br />

the USA, doing the same kind of examination!<br />

On 20 May, the next Saturday, I arrived early in the morning<br />

at Village Music School, armed with my list of instructions<br />

for the day, posters to be put up in conspicuous places,<br />

and food and drink for the examiner, Judy Home, who<br />

arrived shortly after me. (I took my role as host to the examiner<br />

very literally, to her amusement, I suspect). Soon<br />

after that, the first nervous-looking student arrived. (For<br />

USA students, a RACE examination is something totally<br />

new). Judy showed me how she would like the examination<br />

program to be filled out, and then we were ready to<br />

begin, a few minutes ahead of schedule.<br />

As the day went on, students and parents turned up in<br />

drips and drabs, according to their scheduled times, and<br />

I had the opportunity to interact with a number of new<br />

people, and put faces to the names on my lists. It was an<br />

interesting mix of students and parents: some were from<br />

the UK originally and were keen to find a system similar<br />

to those of the ABRSM and Trinity-Guildhall; some were<br />

from Canada where they participated<br />

in RCM exams; others, like<br />

my students, were USA born and<br />

South African Music Teacher |<strong>144</strong> | November <strong>2006</strong><br />

bred — or immigrants, like the young student from Russia<br />

— but keen to investigate something new.<br />

At the end of the day, Judy and I packed up and said goodbye,<br />

both hoping that this was not the last time we would<br />

see each other. (We had got to know each other a bit over<br />

the lunch break that day, when we swapped life stories<br />

over a salad and a cup of tea at the pleasant little café right<br />

next door to the music school.) We expressed our thanks<br />

to Janet Mahoney and her husband (the ‘general manager’)<br />

for their trouble to make the first RACE session at the<br />

North Carolina center in Cary so memorable for everyone<br />

involved. As I drove home that afternoon I felt really<br />

good about how the day went, and proud that I could have<br />

been part of the process of getting RACE established in<br />

North Carolina. I have since ‘handed over the reigns’ to<br />