OdonataTaxonomy_WfHC_PDF - CSIRO

OdonataTaxonomy_WfHC_PDF - CSIRO

OdonataTaxonomy_WfHC_PDF - CSIRO

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Water for a Healthy Country<br />

Taxon Attribute Profiles Order ODONATA<br />

Dragonflies and Damselflies<br />

Introduction<br />

Dragonflies and damselflies are large, strong flying insects<br />

which have fascinated watchers throughout time. They are<br />

among the best known insects, and because of their large size<br />

(usually 30-90 mm, but some species are known up to 150 mm),<br />

captivating behaviour, and ease of identification by the nonspecialist,<br />

they have been referred to as "bird-watchers" insects.<br />

Many species are territorial, and they can display complex and<br />

intriguing behaviour. Dragonflies and damselflies are<br />

components of most riparian ecosystems. Both adult and larval<br />

stages are predaceous, and mostly prey upon other invertebrate<br />

species.<br />

Taxonomy and Ecology<br />

Synopsis of included taxa<br />

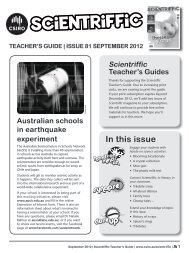

The Odonata includes two suborders: Dragonflies (Anisoptera)<br />

and Damselflies (Zygoptera). Damselflies are smaller and more<br />

delicate, and have the forewing and hindwing similar in shape;<br />

dragonflies tend to be larger and stouter, and have the forewing<br />

and hindwing different in shape, with the base of the hindwing<br />

being wider than that of the forewing. In living specimens, the<br />

dragonflies generally rest with their wings extended, while the<br />

damselflies rest with wings folded together over their back. The<br />

larvae live underwater and breathe through gills. Damselfly<br />

larvae have the gills in the form of three long appendages<br />

extending from the tail end of their abdomen; dragonflies lack<br />

these appendages, and have internal rectal gills.<br />

Dragonfly larvae<br />

Notoaeschna sagittata<br />

Hemianax papuensis<br />

Brachydiplax denticauda

Synthemis macrostigma<br />

Damselfly larvae<br />

Austroargiolestes icteromelas<br />

Austrolestes annulosus<br />

Rhyothemis graphiptera<br />

Indolestes obiri<br />

Nososticta coelestina<br />

The classification of Odonata is not settled. Watson & O'Farrell (1991) and Watson et al., (1991) list 11 families of<br />

damselflies and 6 families of dragonflies, while the ABIF Fauna List shows 12 families of damselflies and 18<br />

families of dragonflies. Despite discrepancies concerning the number of families, authors do agree that there are<br />

just over 300 species of Odonata in Australia (302 in Watson & O'Farrell, 1991; 320 in ABIF).<br />

General overviews of Australian Odonata, including morphology, biology and keys to the suborders and families<br />

are provided by Watson et al. (1991) and Watson & O'Farrell (1991).<br />

2

Life Form<br />

Dragonflies and damselflies are among the best known and recognized insects. Adults are generally large and<br />

elongate, with two pairs of large, membranous wings which have a dense network of veins. The compound eyes are<br />

quite large, and often occupy most of the head. Many species are quite beautiful, with bright metallic markings on<br />

the body, or various banded patterns on the wings. Adults are strong flyers, and are among the fastest of all insects.<br />

The larvae are aquatic, and have elongate, prehensile<br />

mouthparts which they use to capture their prey.<br />

Distribution<br />

Dragonflies and damselflies are widely distributed and<br />

common. Within Australia, they are most diverse in the<br />

tropical regions of north-eastern Queensland and Cape York.<br />

The aquatic habit of the larvae restricts reproduction to water<br />

sources, but lone adults may be found throughout Australia,<br />

often many kilometers from the nearest water source.<br />

Habitat<br />

Dragonflies and damselflies are tied to aquatic habitats.<br />

Although the adults are free living and capable of strong<br />

flight, the other life stages require a riparian habitat.<br />

Dragonfly and damselfly eggs are laid in water. Most<br />

commonly, the hovering females dip their abdomens into the<br />

water to deposit their eggs, and they can frequently be seen<br />

doing this, either singly or still coupled to the male. Larvae<br />

spend their entire life submerged in water, where they are predators on other small aquatic organisms. Various<br />

species can occupy most freshwater habitats, including waterfalls, torrents, streams, lakes, ponds, swamps, bogs<br />

and estuaries.<br />

Adult emergence takes place when the larva crawls up out of the water<br />

onto a rock or branch, firmly grasps the substrate with its legs, and the<br />

adult emerges from the cast larval skin. Adults are strong flyers. Males<br />

are often territorial, and can be observed returning to a favourite perch<br />

where they observe their territory and are ready to fly out to capture<br />

food or guard against other males.<br />

Status in Community<br />

Both adults and larvae are predaceous, and will be responsible for<br />

removing numerous prey items during their life. Adults catch other<br />

invertebrates which they eat during flight. Larval prey items are<br />

generally other invertebrates, but larger species can take small fish and<br />

tadpoles.<br />

Cast skins of Hemicordulia tau<br />

3

Reproduction and Establishment<br />

Reproduction<br />

The Odonata are unusual in that the male has secondary genitalia at the base of the abdomen, to which he transfers<br />

sperm prior to mating. This produces a very characteristic coupling pose, where the male grasps the female behind<br />

the head with claspers at the end of his abdomen, and the female places the tip of her abdomen up to the base of the<br />

male abdomen. Elaborate courtship rituals are often precede mating.<br />

Dispersability<br />

Coenagrion lyelli<br />

Eusynthemis virgula<br />

Animals which inhabit standing, often temporary, water sources often display the ability for dispersal and<br />

migration over great distances. Adult dragonflies are strong fliers, and even though their larvae require water, lone<br />

adults are often seen great distances from water. This enables them to recolonize patches of standing water that are<br />

either unsuitable or non-existent during parts of the year.<br />

Juvenile period<br />

Larvae vary in habit, but all are aquatic. They can moult up to 15 times before they reach the final instar and are<br />

ready to emerge. All larvae are predaceous, and they are generally ambush predators which remain concealed in<br />

silt, or under rocks and plants, waiting for slow-moving prey. Odonata larvae are unusual in having hinged,<br />

prehensile mouthparts with strong teeth which they can shoot out to capture their prey.<br />

Hydrology and Salinity<br />

Salinity Tolerance<br />

Kefford et al. (2003) reported Odonata to be more tolerant to salinity than many other aquatic macroinvertebrates;<br />

however, Bailey et al. (2002), Gooderham & Tsyrlin (2002) and Chessman (2003) showed a wide range of<br />

tolerance within the group. For example, on the SIGNAL 2 grades of 1-10 (1 being least sensitive and 10 being<br />

most sensitive), Odonata families ranged from 1 (Lestidae) to 10 (Austrocorduliidae) (Chessman, 2003).<br />

Flooding Regimes<br />

Alternating periods of flooding and drought could affect dragonfly and damselfly larvae, which need water for<br />

survival. The strong flying ability of adults will allow recolonization of aquatic habitats after periods of drought.<br />

Several species of Australian Odonata have larvae that are drought resistant, and can survive temporarily in an<br />

inactive state if free water is withdrawn (Watson, 1982).<br />

4

Conservation Status<br />

Hawking (1999) reviewed the conservation status of 314 Australian dragonflies and damselflies. Of the 314 known<br />

Australian species, 1 was listed as Critically Endangered, 12 Endangered, 24 Vulnerable, 39 Near Threatened, 84<br />

Data Deficient, and the remaining 154 Least Concern.<br />

The critically endangered species, Adams emerald dragonfly (Archaeophya adamsi), is one of Australia's rarest<br />

dragonflies, with only 5 adults having been captured. The species is known only from the greater Sydney region,<br />

and some remaining habitats are under threat from development.<br />

Hawking (1999) pointed out three major concerns: 1) the large number of endangered species, 2) the large number<br />

of species which deserve priority conservation action; 3) the number of species where there is insufficient data to<br />

make a proper assessment.<br />

Uses<br />

Although there are no records of Aboriginal use of dragonflies or damselflies as food, it is not unlikely that certain<br />

species were eaten. It is well known that many insect species were eaten by Aborigines (Tindale, 1966); and the use<br />

of dragonflies and damselflies as food items in Asia and elsewhere in the world is well documented (Pemberton,<br />

1995; Ramos-Elorduy, 1998; Menzel & D'Alusio, 1998).<br />

Summary<br />

Several authors have suggested that macroinvertebrates, including Odonata, can be effectively included in<br />

programs for monitoring water quality (Watson, 1982; Water and Rivers Commission, 1996; Chessman, 2003;<br />

Minnesota Pollution Control Agency, 2004). Due to the variability of response to environmental factors within the<br />

order, certain groups may be much more suitable as bioindicator species than others. The fact remains that they are<br />

large, easy to observe, and can be recognized by non-specialists, making them a very suitable group for a variety of<br />

monitoring purposes.<br />

5

List of MDB Species<br />

Table 1. Odonata recorded from the Murray Darling Basin<br />

(Classification from Houston et al., 1999).<br />

DAMSELFLIES DRAGONFLIES<br />

Coenagrionidae Aeshnidae<br />

Austroagrion watsoni Lieftinck, 1982 Aeshna brevistyla (Rambur)<br />

Austrocnemis splendida (Martin, 1901) Aeshna brevistyla (Rambur)<br />

Caliagrion billinghursti (Martin, 1901) Austrogynacantha heterogena Tillyard, 1908<br />

Coenagrion lyelli (Tillyard, 1913) Hemianax papuensis (Burmeister, 1839)<br />

Ischnura aurora aurora (Brauer, 1865)<br />

Ischnura heterosticta (Burmeister, 1839) Austrocorduliidae<br />

Pseudagrion aureofrons Tillyard, 1906 Apocordulia macrops Watson, 1980<br />

Pseudagrion ignifer Tillyard, 1906 Austrocordulia refracta Tillyard, 1909<br />

Xanthagrion erythroneurum (Selys, 1876)<br />

Austropetaliidae<br />

Diphlebiidae Austropetalia patricia (Tillyard, 1909)<br />

Diphlebia lestoides lestoides (Selys, 1853)<br />

Diphlebia lestoides tillyardi Fraser, 1956 Cordulephyidae<br />

Diphlebia nymphoides Tillyard, 1912 Cordulephya pygmaea Selys, 1870<br />

Hemiphlebiidae Gomphidae<br />

Hemiphlebia mirabilis Selys, 1869 Antipodogomphus acolythus (Martin, 1901)<br />

Austrogomphus amphiclitus (Selys, 1873)<br />

Isostictidae Austrogomphus angeli Tillyard, 1913<br />

Rhadinosticta simplex (Martin, 1901) Austrogomphus australis Dale, 1854<br />

Austrogomphus cornutus Watson, 1991<br />

Lestidae Austrogomphus divaricatus Watson, 1991<br />

Austrolestes analis (Rambur, 1842) Austrogomphus guerini (Rambur, 1842)<br />

Austrolestes annulosus (Selys, 1862) Austrogomphus melaleucae Tillyard, 1909<br />

Austrolestes aridus (Tillyard, 1908) Austrogomphus ochraceus (Selys, 1869)<br />

Austrolestes cingulatus (Burmeister, 1839) Hemigomphus gouldii (Selys, 1854)<br />

Austrolestes io (Selys, 1862) Hemigomphus heteroclytus Selys, 1854<br />

Austrolestes leda (Selys, 1862)<br />

Austrolestes psyche (Hagen, 1862) Hemicorduliidae<br />

Hemicordulia australiae (Rambur, 1842)<br />

6

Megapodagrionidae Hemicordulia intermedia (Selys, 1871)<br />

Austroargiolestes amabilis (Forster, 1899) Hemicordulia superba Tillyard, 1911<br />

Austroargiolestes brookhousei Theischinger &<br />

O'Farrell, 1986<br />

Hemicordulia tau (Selys, 1871)<br />

Austroargiolestes calcaris (Fraser, 1958) Procordulia jacksoniensis (Rambur, 1842)<br />

Austroargiolestes christine Theischinger &<br />

O'Farrell, 1986<br />

Austroargiolestes icteromelas (Selys, 1862) Libellulidae<br />

Austroargiolestes isabellae Theischinger &<br />

O'Farrell, 1986<br />

Austrothemis nigrescens (Martin, 1901)<br />

Griseargiolestes eboracus (Tillyard, 1913) Crocothemis nigrifrons (Kirby, 1894)<br />

Griseargiolestes griseus (Hagen, 1862) Diplacodes bipunctata (Brauer, 1865)<br />

Griseargiolestes intermedius (Tillyard, 1913) Diplacodes haematodes (Burmeister, 1839)<br />

Nannophlebia risi Tillyard, 1913<br />

Nannophya dalei (Tillyard, 1908)<br />

Protoneuridae Orthetrum caledonicum (Brauer, 1865)<br />

Nososticta solida (Hagen, 1860) Orthretrum villosovittatum villosovittatum<br />

(Brauer, 1868)<br />

Pantala flavescens (Fabricius, 1898)<br />

Synlestidae Trapezostigma loewii (Kaup, 1866)<br />

Synlestes selysi Tillyard, 1917<br />

Synlestes weyersii tillyardi Fraser, 1948 Synthemistidae<br />

Archaeosynthemis orientalis (Tillyard, 1910)<br />

Choristhemis flavoterminata (Martin, 1901)<br />

Eusynthemis aurolineata (Tillyard, 1913)<br />

Eusynthemis brevistyla (Selys, 1871)<br />

Eusynthemis guttata (Selys, 1871)<br />

Eusynthemis tillyardi Theischinger, 1995<br />

Eusynthemis virgula (Selys, 1874)<br />

Parasynthemis regina (Selys, 1874)<br />

Synthemis eustalacta (Burmeister, 1839)<br />

Telephlebiidae<br />

Austroaeschna atrata Martin, 1909<br />

Austroaeschna flavomaculata Tillyard, 1916<br />

Austroaeschna inermis Martin, 1901<br />

Austroaeschna multipunctata (Martin, 1901)<br />

Austroaeschna obscura Theischinger, 1982<br />

7

References<br />

Austroaeschna parvistigma (Selys, 1883)<br />

Austroaeschna pulchra Tillyard, 1909<br />

Austroaeschna sigma Theischinger, 1982<br />

Austroaeschna subapicalis Theischinger, 1982<br />

Austroaeschna unicornis unicornis<br />

(Martin,1901)<br />

Notoaeschna geminata Theischinger, 1982<br />

Notoaeschna sagittata (Martin, 1901)<br />

Spinaeschna tripunctata (Martin, 1901)<br />

Telephlebia brevicauda Tillyard, 1916<br />

Telephlebia cyclops Tillyard, 1916<br />

Telephlebia godeffroyi Selys, 1883<br />

Telephlebia tillyardi Campion, 1916<br />

Bailey, P., Boon, P. & Morris, K. (2002) Australian Biodiversity Salt Sensitivity Database. Land & Water<br />

Australia. http://www.rivers.gov.au/research/contaminants/saltsen.htm<br />

Chessman, B. (2003) SIGNAL 2 - A Scoring System for Macroinvertebrate ('Water Bugs') in Australian<br />

Rivers, Monitoring River Heath Initiative Technical Report no 31, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra.<br />

http://www.deh.gov.au/water/rivers/nrhp/signal/<br />

Gooderham, J. & Tsyrlin, E. (2002) The Waterbug Book: a guide to the freshwater macroinvertebrates of<br />

temperate Australia. <strong>CSIRO</strong> Publishing.<br />

Hawking, J.H. (1999) An evaluation of the current conservation status of Australian dragonflies (Odonata).<br />

Pp 354-360, in: W. Ponder & D. Lunney (eds), The Other 99%. The Conservation and Biodiversity of<br />

Invertebrates. Transactions of the Royal Zoological Society of New South Wales, Mosman.<br />

Houston, W.W.K., Watson, J.A.L. & Calder, A.A. (1999) Australian Faunal Directory: Checklist for<br />

Odonata. Australian Biological Resources Survey, Department of the Environment and Heritage.<br />

http://www.deh.gov.au/cgi-bin/abrs/abif-fauna/tree.pl?pstrVol=ODONATA&pintMode=1<br />

Kefford, B.J., Papas, P.J., Nugegoda, D. (2003) Relative salinity tolerance of macroinvertebrates from the<br />

Barwon River, Victoria, Australia. Marine and Freshwater Research, 54: 755-765.<br />

Menzel, P. & D'Alusio, F. (1998) Man Eating Bugs: The Art and Science of Eating Insects. Ten Speed<br />

Press, Hong Kong.<br />

Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (2004). Wetlands: Monitoring Aquatic Invertebrates.<br />

http://www.pca.state.mn.us/water/biomonitoring/bio-wetlands-invert.html<br />

Pemberton, R. W. (1995) Catching and eating dragonflies in Bali and elsewhere in Asia. American<br />

Entomologist, 41: 97-102<br />

8

Ramos-Elorduy, J. (1998) Creepy Crawly Cuisine: The Gourmet Guide to Edible Insects. Park Street Press,<br />

Rochester, Vermont.<br />

Tindale, N.B. (1966) Insects as food for the Australian Aborigines. Australian Natural History, 15(6), p.<br />

179-183.<br />

Water and Rivers Commission (1996). Macroinvertebrates & Water Quality. Water Facts 2.<br />

http://www.wrc.wa.gov.au/public/waterfacts/2_macro/WF2.pdf<br />

Watson, J.A.L. (1982) Dragonflies in the Australian environment: taxonomy, biology and conservation.<br />

Adv. Odonatol., 1: 293-302.<br />

Watson, J.A.L. & O'Farrell, A.F. (1991) Odonata (dragonflies and damselflies). Pp. 294-310, in Insects of<br />

Australia: A textbook for students and research workers. <strong>CSIRO</strong>. 2 nd Edition.<br />

Watson, J.A.L., Theischinger, G. & Abbey, H.M. (1991) The Australian Dragonflies: A Guide to the<br />

Identification, Distributions and Habitats of Australian Odonata. <strong>CSIRO</strong>.<br />

More information contact:<br />

Dr Judy West<br />

02 6246 5113<br />

judy.west@csiro.au<br />

www.csiro.au<br />

9