By Jean C. Florman - College of Liberal Arts & Sciences - The ...

By Jean C. Florman - College of Liberal Arts & Sciences - The ...

By Jean C. Florman - College of Liberal Arts & Sciences - The ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

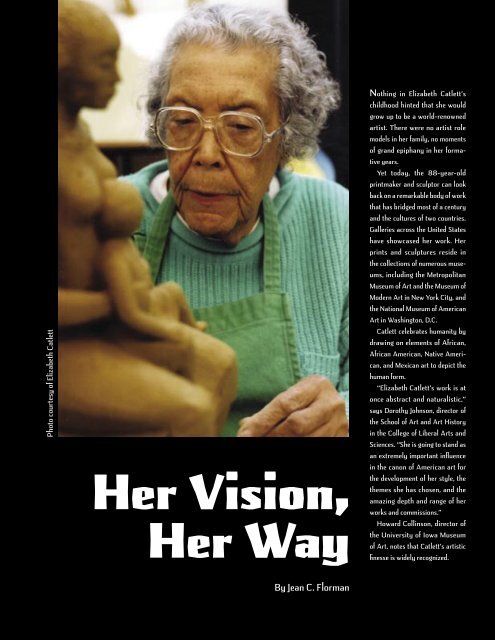

Photo courtesy <strong>of</strong> Elizabeth Catlett<br />

Her Vision,<br />

Elizabeth Catlett<br />

Her Way<br />

<strong>By</strong> <strong>Jean</strong> <strong>Florman</strong><br />

<strong>By</strong> <strong>Jean</strong> C. <strong>Florman</strong><br />

Nothing in Elizabeth Catlett’s<br />

childhood hinted that she would<br />

grow up to be a world-renowned<br />

artist. <strong>The</strong>re were no artist role<br />

models in her family, no moments<br />

<strong>of</strong> grand epiphany in her formative<br />

years.<br />

Yet today, the 88-year-old<br />

printmaker and sculptor can look<br />

back on a remarkable body <strong>of</strong> work<br />

that has bridged most <strong>of</strong> a century<br />

and the cultures <strong>of</strong> two countries.<br />

Galleries across the United States<br />

have showcased her work. Her<br />

prints and sculptures reside in<br />

the collections <strong>of</strong> numerous museums,<br />

including the Metropolitan<br />

Museum <strong>of</strong> Art and the Museum <strong>of</strong><br />

Modern Art in New York City, and<br />

the National Museum <strong>of</strong> American<br />

Art in Washington, D.C.<br />

Catlett celebrates humanity by<br />

drawing on elements <strong>of</strong> African,<br />

African American, Native American,<br />

and Mexican art to depict the<br />

human form.<br />

“Elizabeth Catlett’s work is at<br />

once abstract and naturalistic,”<br />

says Dorothy Johnson, director <strong>of</strong><br />

the School <strong>of</strong> Art and Art History<br />

in the <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Liberal</strong> <strong>Arts</strong> and<br />

<strong>Sciences</strong>. “She is going to stand as<br />

an extremely important influence<br />

in the canon <strong>of</strong> American art for<br />

the development <strong>of</strong> her style, the<br />

themes she has chosen, and the<br />

amazing depth and range <strong>of</strong> her<br />

works and commissions.”<br />

Howard Collinson, director <strong>of</strong><br />

the University <strong>of</strong> Iowa Museum<br />

<strong>of</strong> Art, notes that Catlett’s artistic<br />

finesse is widely recognized.<br />

<strong>The</strong> University <strong>of</strong> Iowa 7

8 <strong>Arts</strong> & <strong>Sciences</strong><br />

“All <strong>of</strong> Catlett’s works—whether 18 inches<br />

or four feet tall—are magnificently crafted. She<br />

pays particular attention to surfaces, and even<br />

the bronzes have a beautiful texture.”<br />

Catlett was born in 1915. Her father, who had<br />

taught mathematics at Tuskeegee University,<br />

succumbed to tuberculosis shortly before Elizabeth<br />

was born. Left with three children to support,<br />

Elizabeth’s mother became a truant <strong>of</strong>ficer<br />

in Washington, D.C. She taught her children to<br />

follow their dreams by becoming educated, a<br />

lesson she had learned from her own parents.<br />

“Education was very important to my mother’s<br />

parents, who had been slaves,” Catlett<br />

says. “After the Civil War, they made sure that<br />

all four <strong>of</strong> their sons graduated from university<br />

and all four <strong>of</strong> their daughters graduated from<br />

seminary school.”<br />

Catlett followed suit. In 1935 she graduated<br />

cum laude from Howard University with<br />

a B.S. degree in printmaking, drawing, and art<br />

history. She then became an educator herself,<br />

teaching art in a North Carolina high school for<br />

two years.<br />

<strong>By</strong> 1938 she had decided to continue her<br />

formal training at an artistic mecca in the Midwest.<br />

At <strong>The</strong> University <strong>of</strong> Iowa, she studied<br />

with sculptor Henry Stinson and regionalist<br />

painter Grant Wood.<br />

“Grant Wood was a very generous teacher,”<br />

Catlett says, “and he influenced all my work.<br />

He would tell his students, ‘Paint what you<br />

know.’ ”<br />

For Catlett, that mostly meant black women.<br />

<strong>The</strong> mother-child bond, a recurring motif in her<br />

work, was inspired by the strong bond with her<br />

own mother and grandmothers.<br />

“For Grant Wood’s class, I painted a young<br />

girl ironing,” Catlett recalls. “My grandmother<br />

taught me to iron. First I started with overalls,<br />

then overall shirts. <strong>The</strong>n I finally graduated to<br />

dress shirts. I’m a good ironer, so that’s what<br />

I painted.”<br />

While at Iowa, Catlett spent many 11-hour<br />

days and weekends in the school’s art studios.<br />

Her $35-per-month budgeted expenses<br />

included $10 rent for a room in a local home.<br />

At the time, African American students were<br />

not allowed to live in University residence<br />

halls, so the young artist roomed in the home<br />

<strong>of</strong> a Mrs. Scott.<br />

Catlett says that because she had grown<br />

up in Washington, D.C., a city divided by clear<br />

and unyielding race lines, Iowa’s combination<br />

<strong>of</strong> openness and segregation<br />

surprised her.<br />

“I’d lived in an African<br />

American culture my whole<br />

life,” she says. “In Iowa City, I<br />

suddenly was living among white<br />

people, but I still couldn’t do things<br />

like live in the dorms.”<br />

Although Catlett excelled in her course<br />

work, the University almost didn’t award<br />

her a degree. Near the end <strong>of</strong> her final<br />

semester, she was told that she could not<br />

receive an M.F.A. because she had not taken<br />

printmaking.<br />

“<strong>The</strong> head <strong>of</strong> the department apparently<br />

was unhappy because I had taken a bronze<br />

foundry course at the <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> Engineering<br />

instead <strong>of</strong> printmaking,” she says. “I had<br />

taken the engineering course to learn about<br />

lost wax and sand casting.”<br />

At the time, the school’s art gallery<br />

was displaying Catlett’s graduate work,<br />

including stone carvings, cast cement<br />

nudes, a fresco painting, terra-cotta<br />

masks, and a bronze mask—one <strong>of</strong><br />

the three pieces she created during<br />

the engineering course. Catlett says<br />

the issue still hadn’t been settled<br />

by the day <strong>of</strong> her thesis defense,<br />

and at the end <strong>of</strong> her defense,<br />

her committee sent her out <strong>of</strong><br />

the room.<br />

“I waited for the longest<br />

time,” she says. “Finally, Grant<br />

Wood came out and said, ‘Congratulations.<br />

You have earned<br />

your degree.’ ”

Catlett and two other students earned the<br />

first M.F.A. degrees awarded by the University.<br />

Her graduate thesis project, a stone carving <strong>of</strong><br />

a black mother and child, earned first prize in<br />

Chicago’s 1940 American Negro Exposition<br />

and then graced the University campus for<br />

many years.<br />

Following graduation, Catlett taught at several<br />

schools, including Dillard University in<br />

New Orleans, where she became head <strong>of</strong> the<br />

art department. During a summer spent learning<br />

ceramic techniques at the Art Institute <strong>of</strong><br />

Chicago, she met and married her first husband,<br />

artist Charles White. In 1944 the couple<br />

moved to New York City, where she served<br />

two years as a fund-raiser and teacher at the<br />

George Washington Carver School in Harlem.<br />

“<strong>The</strong> people who came to the school worked<br />

all day as laundresses, elevator operators, and<br />

domestics, and then went to class from seven<br />

to ten at night,” Catlett says. “We charged<br />

three dollars a course, and most <strong>of</strong> the teachers<br />

were volunteers.<br />

“I discovered that these were the people<br />

I wanted to create art for,” she adds. “<strong>The</strong>se<br />

were humble, hardworking, intelligent people,<br />

hungry for culture and for education. <strong>The</strong>y<br />

embraced everything—authors who came to<br />

visit the school, musicians from Juilliard, art at<br />

the Metropolitan.”<br />

During her tenure at the Carver School,<br />

Catlett continued to mature as an artist. Russian<br />

sculptor Ossip Zadkine, who was living in<br />

New York, became her mentor. Her work was<br />

exhibited in the New Orleans Museum <strong>of</strong> Art<br />

and the Modern Art Museum <strong>of</strong> Mexico, and in<br />

1945 she won the first <strong>of</strong> two grants from the<br />

Julius Rosenwald Foundation. Catlett used the<br />

grants to study public art in Mexico City.<br />

Years before, a brief stint with the<br />

Depression-era Public Works Administration<br />

had sparked Catlett’s fascination with public<br />

art. As a sophomore at Howard University,<br />

she had been employed briefly by the PWA<br />

as a muralist.<br />

“I was supposed to paint a mural for the<br />

dome <strong>of</strong> a local teacher’s college,” she recalls,<br />

“but I had never seen a mural, and didn’t know<br />

what one was supposed to look like. So I went<br />

to school all week, worked on Friday nights,<br />

and then spent Saturdays in the Congressional<br />

Library looking up everything I could<br />

find about murals. I became fascinated by the<br />

murals <strong>of</strong> Diego Rivera, but never really understood<br />

how I was supposed to actually create a<br />

two-foot-high painting around a circular dome.<br />

After five weeks, I was fired.”<br />

Nevertheless, Catlett says, the experience<br />

gave her two things: a love <strong>of</strong> large-scale public<br />

art and an understanding that opportunities<br />

should be seized. Both helped ease her into the<br />

heady art world <strong>of</strong> mid-century Mexico, where<br />

she moved in 1946. Catlett quickly became<br />

part <strong>of</strong> the vibrant inner circle <strong>of</strong> Latin American<br />

Social Realists that included Rivera, Frida<br />

Kahlo, David Alfaro Siquerios, and painter<br />

Francisco Mora. When Catlett and Mora fell<br />

in love, she divorced her first husband. Mora<br />

died in 2002, but the couple enjoyed 56 years<br />

<strong>of</strong> marriage strengthened by shared artistic<br />

ambitions, political passions, and parenthood.<br />

In Mexico, Catlett found an environment<br />

that welcomed and nurtured artists. She was<br />

appointed the first woman to head the sculpture<br />

department at the National School <strong>of</strong><br />

Fine <strong>Arts</strong>, in Mexico City, a position she held<br />

from 1959 until 1976. Because she wanted<br />

to exercise her political rights in her adopted<br />

home, Catlett became a citizen <strong>of</strong> Mexico in<br />

1962. Today she divides her time between her<br />

Cuernavaca home outside Mexico City and an<br />

apartment in New York City.<br />

In 1996 <strong>The</strong> University <strong>of</strong> Iowa awarded<br />

Catlett the Distinguished Alumni Award.<br />

Iowa’s Museum <strong>of</strong> Art owns a Catlett linocut,<br />

“Sharecropper (Cosechadora de algodon),”<br />

and the University has commissioned a sixfoot-high<br />

bronze statue for display on campus.<br />

Above: “Sharecropper,” 1968, linocut, 25 9/16 x 19 12/16 inches,<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Iowa Museum <strong>of</strong> Art, purchased by the friends <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Jean</strong> Davidson<br />

Left: “Stepping Out,” 2000, bronze, 30 inches, courtesy <strong>of</strong> June<br />

Kelly Gallery, New York City<br />

Recently the artist won a competition to<br />

honor African American writer Ralph Ellison.<br />

Her 15-foot bronze will be installed in<br />

New York City near the apartment where the<br />

author’s widow still lives. Catlett also has been<br />

commissioned to create three pieces honoring<br />

civil rights activist Mary Church Terrell.<br />

“When I went to Washington, D.C., to chat<br />

about the work,” Catlett says, “I walked into<br />

the meeting room and there were 15 people<br />

sitting there telling me where the sculpture<br />

was going to go, what it should look like, what<br />

materials I should use. I let it go on for a while,<br />

and then I said, ‘I’m not listening to you.’ <strong>The</strong>y<br />

were very surprised.”<br />

<strong>The</strong>re is no doubt Catlett is an artist to be<br />

reckoned with. She continues to work every<br />

day except Sunday, and until two years ago,<br />

she still wielded a chain saw to rough out her<br />

wood sculptures. Her humanism and compassion<br />

for the ordinary individual suffuse every<br />

curved arm cradling a child and sharp chin<br />

tilted upward in grace and defiance. <strong>By</strong> following<br />

Grant Wood’s gentle advice to “depict<br />

what you know,” Catlett has used the language<br />

<strong>of</strong> her own heritage and experience to speak to<br />

the world.<br />

<strong>The</strong> University <strong>of</strong> Iowa 9