download - InstantEncore

download - InstantEncore

download - InstantEncore

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

10-13 Mahler:Layout 1 10/3/11 11:38 AM Page 27<br />

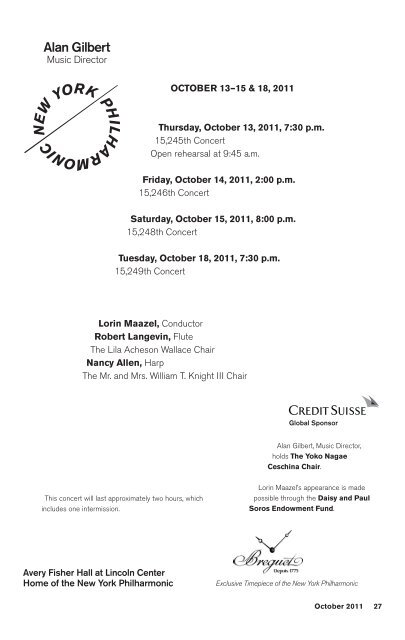

OCTOBER 13–15 & 18, 2011<br />

Thursday, October 13, 2011, 7:30 p.m.<br />

15,245th Concert<br />

Open rehearsal at 9:45 a.m.<br />

Friday, October 14, 2011, 2:00 p.m.<br />

15,246th Concert<br />

Saturday, October 15, 2011, 8:00 p.m.<br />

15,248th Concert<br />

Tuesday, October 18, 2011, 7:30 p.m.<br />

15,249th Concert<br />

Lorin Maazel, Conductor<br />

Robert Langevin, Flute<br />

The Lila Acheson Wallace Chair<br />

Nancy Allen, Harp<br />

The Mr. and Mrs. William T. Knight III Chair<br />

This concert will last approximately two hours, which<br />

includes one intermission.<br />

Avery Fisher Hall at Lincoln Center<br />

Home of the New York Philharmonic<br />

Global Sponsor<br />

Alan Gilbert, Music Director,<br />

holds The Yoko Nagae<br />

Ceschina Chair.<br />

Lorin Maazel’s appearance is made<br />

possible through the Daisy and Paul<br />

Soros Endowment Fund.<br />

Exclusive Timepiece of the New York Philharmonic<br />

October 2011<br />

27

10-13 Mahler:Layout 1 10/3/11 11:38 AM Page 28<br />

New York Philharmonic<br />

Lorin Maazel, Conductor<br />

Robert Langevin, Flute, The Lila Acheson Wallace Chair<br />

Nancy Allen, Harp, The Mr. and Mrs. William T. Knight III Chair<br />

MOZART Symphony No. 38 in D major, Prague, K.504 (1786)<br />

(1756–91) Adagio — Allegro<br />

Andante<br />

Finale: Presto<br />

MOZART Concerto in C major for Flute and Harp,<br />

K.299/297c (1778)<br />

Allegro<br />

Andantino<br />

Rondeau: Allegro<br />

ROBERT LANGEVIN<br />

NANCY ALLEN<br />

Intermission<br />

DEBUSSY Jeux: Poème dansé (1912–13)<br />

(1862–1918) Très lent — Scherzando (Tempo initial)<br />

DEBUSSY Ibéria, from Images for Orchestra (1905–08)<br />

By the Highways and By-ways<br />

Parfumes of the Night<br />

Morning of a Festival Day<br />

(The second and third movements are played without pause)<br />

28<br />

Classical 105.9 FM WQXR is the Radio Station of<br />

the New York Philharmonic.<br />

The New York Philharmonic This Week,<br />

nationally syndicated on the WFMT Radio Network,<br />

is broadcast 52 weeks per year; visit nyphil.org<br />

for information.<br />

New York Philharmonic<br />

The New York Philharmonic’s concert-recording<br />

series, Alan Gilbert and the New York Philharmonic:<br />

2011–12 Season, will be available for<br />

<strong>download</strong> this fall at all major online music stores.<br />

Visit nyphil.org/recordings for more information.<br />

Follow us on Facebook, Tumblr, Twitter, and<br />

YouTube.<br />

Please be sure that your cell phones and electronic devices have been silenced.

10-13 Mahler:Layout 1 10/3/11 11:38 AM Page 29<br />

Notes on the Program<br />

By James M. Keller, Program Annotator<br />

The Leni and Peter May Chair<br />

Symphony No. 38 in D major,<br />

Prague, K.504<br />

Concerto in C major for Flute<br />

and Harp, K.299/297c<br />

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart<br />

When Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart left his native<br />

provincial Salzburg for the exciting Austrian<br />

capital of Vienna in 1781, he seems to have<br />

assumed that the world would be his oyster.<br />

This was not to be, however. He met with a<br />

good measure of success, to be sure, gaining<br />

a following as a virtuoso pianist and as a composer<br />

— the latter even in the high-stakes<br />

world of the musical theater — but Vienna<br />

was full of other talented<br />

composers, and many of<br />

them were more politically<br />

savvy than Mozart, whose<br />

genius was often accompanied<br />

by an obstreperous<br />

streak. The decade<br />

he would spend in Vienna<br />

(where he died in 1791)<br />

might be characterized<br />

as a love-hate relationship<br />

in which Mozart<br />

derived important aesthetic<br />

sustenance from<br />

the city’s cultural life<br />

but often felt personally<br />

underappreciated.<br />

Not so Prague — which<br />

Mozart also loved, and<br />

which loved him back.<br />

Germany, Austria, and<br />

In Short<br />

Born: January 27, 1756, in Salzburg, Austria<br />

Died: December 5, 1791, in Vienna<br />

Bohemia shared an active cultural exchange<br />

in the 18th century. In the balance of artistic<br />

trade, Bohemia seems to have been a net exporter:<br />

its gifts to the musical world included<br />

the flotilla of Czech musicians who elevated<br />

Mannheim (in southern Germany) into a midcentury<br />

musical center so prominent that its<br />

orchestra set the standard to which all others<br />

aspired. For all its openness to outsiders,<br />

Prague seems not to have attracted immigrants<br />

quite so easily. Its welcome mat was<br />

out to Mozart, though, and its music-loving<br />

populace was quick to embrace such operas<br />

as Le nozze di Figaro and Don Giovanni unconditionally,<br />

even when Vienna had given<br />

them a more guarded reception. Franz Xaver<br />

Works composed and premiered: Symphony No. 38: composed 1786, in<br />

Vienna; Mozart entered it into his catalogue of compositions on December 6;<br />

premiered apparently January 19, 1787, in Prague, Bohemia (now Czech Republic),<br />

the composer conducting<br />

Concerto for Flute and Harp: composed April 1778 in Paris; we have no information<br />

about the early performance history of this work<br />

New York Philharmonic premieres and most recent performances:<br />

Symphony No. 38: premiered January 27, 1866, Carl Bergmann, conductor; most<br />

recently performed November 10, 2009, Neeme Järvi, conductor<br />

Concerto for Flute and Harp: premiered October 17, 1931, Erich Kleiber, conductor,<br />

John Amans, flute, and Theodore Cella, harp; most recently performed February 24,<br />

2007, Lorin Maazel, conductor, Robert Langevin, flute, and Nancy Allen, harp<br />

Estimated durations: Symphony No. 38: ca. 29 minutes; Concerto for Flute and<br />

Harp: ca. 29 minutes<br />

October 2011<br />

29

10-13 Mahler:Layout 1 10/3/11 11:38 AM Page 30<br />

Niemetschek, the composer’s early biographer,<br />

clarified the difference when recounting<br />

the first performances of Mozart’s Figaro:<br />

In Vienna … they slandered him and did<br />

their best to belittle his art…. [In Prague]<br />

the enthusiasm shown by the public was<br />

without precedent; they could not hear it<br />

enough.<br />

In 1786 Mozart received an invitation to<br />

visit Prague — apparently extended by a coterie<br />

of culturally inclined citizens of the city’s<br />

German-speaking community, well known for<br />

its patriotic support of the Austro-Germanic<br />

arts. At the beginning of 1787 Mozart, his<br />

wife, and a considerable entourage (including<br />

their dog) traveled by coach to the Bohemian<br />

capital for what would be the closest<br />

the composer ever came to a pleasure trip.<br />

His musical obligations were few, limited to<br />

an evening conducting Le nozze di Figaro<br />

and a couple of performances as a pianist,<br />

during which he particularly distinguished<br />

himself as an improviser.<br />

Mozart had arrived bearing gifts, chief<br />

among them the Symphony in D major<br />

that he had completed late in 1786 and that<br />

Listen for … Echoes of Figaro<br />

would forever have the name of “Prague” attached<br />

to it. Mozart led a distinguished<br />

orchestra — albeit a small one of about 20<br />

players — in the work’s premiere, which appears<br />

to have taken place on January 19, 1787.<br />

Years later, in 1808, Niemetschek reported:<br />

the symphonies he composed for this occasion<br />

are real masterpieces … full of surprising<br />

modulations, and have a quick, fiery<br />

gait, so that the very soul is transported to<br />

sublime heights. This applies particularly<br />

to the Symphony in D major, which remains<br />

a favorite in Prague, although it has<br />

doubtless been heard a hundred times.<br />

Indeed, this is one of Mozart’s most impressive<br />

symphonies — in spite of its having<br />

only three movements rather than the by<br />

then traditional four. What’s missing is the<br />

minuet-and-trio that normally occupies the<br />

third movement of a classical symphony. No<br />

one knows why Mozart decided not to include<br />

one, but he more than compensates<br />

for its absence by attaching a slow introduction<br />

to the opening Allegro. Although such<br />

introductions are found in the later symphonies<br />

of Haydn and in those of Beethoven,<br />

Commentators are wont to find both Don Giovanni and Die Zauberflöte prefigured in the Prague Symphony;<br />

but one might just as easily hear reflections of the good-humored wisdom of Le nozze di Figaro as the moody<br />

introduction gives way to the main stretch of the first movement, where the drama of quiet syncopations gives<br />

way to jubilant outbursts from the trumpets and timpani. The spirit of Figaro again returns with the concluding<br />

Presto — and quite directly so, since its main theme is derived from that opera, or in any case relates closely<br />

to the fleeting duet between Susanna and Cherubino (Act II, scene 7) that culminates in the latter leaping from<br />

the window of the Countess’s boudoir:<br />

Mozart wrote this movement at about the same time he was completing Figaro. Just why he embarked on a<br />

stand-alone D-major symphonic Presto in the spring of 1786 remains a mystery, but, practical craftsman that<br />

he was, Mozart found a use for it later that year and built the rest of his symphony to fit with it.<br />

30<br />

New York Philharmonic

10-13 Mahler:Layout 1 10/3/11 11:38 AM Page 31<br />

they are not much associated with Mozart. In<br />

this opening, Mozart seems to be looking<br />

ahead to the perplexing chromatic ruminations<br />

of Don Giovanni, which, as it happens,<br />

Prague would giddily idolize within a year.<br />

By the time Mozart turned 21, in January<br />

1777, he had already experienced more of<br />

the world than most young adults of any era<br />

would approach in a lifetime. As a child<br />

prodigy, he had impressed musical connoisseurs<br />

and had entertained crowned heads in<br />

At the Time<br />

many European capitals. When he reached<br />

his majority, Mozart’s compositions at least<br />

equaled and often surpassed the best work<br />

of his contemporaries, and he had begun to<br />

make a mark in all the major genres. However,<br />

the young composer felt repressed in<br />

what he viewed as the artistic backwater of<br />

Salzburg, and he yearned to pursue his career<br />

elsewhere.<br />

In September 1777 Mozart and his mother<br />

embarked on a journey north and west, tracing<br />

a route from their home in Salzburg to<br />

In the years 1786–87, when Mozart composed and premiered his Symphony No. 38, the following events were<br />

taking place:<br />

1786: Jacques Balmat and Dr. Michel-Gabriel Paccard become the first<br />

men to climb France’s Mont Blanc; Robert Burns (top right) publishes<br />

Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect, his first book of poetry; Charles<br />

Cornwallis, whose surrender to American forces at Yorktown signaled<br />

the end of major fighting in the American Revolution, is appointed governor-general<br />

of India; George Washington calls for the abolition of slavery;<br />

the Necklace Affair (“L’Affiare du Collier”) trial ends in Paris; Reykjavík,<br />

the capital of Iceland, is founded; Johann Wolfgang von Goethe embarks<br />

on his travels to Italy; Daniel Shays, a Revolutionary War veteran, leads a<br />

rebellion that begins in Springfield, Massachusetts, to protest evictions<br />

and seizure of property for non-payment of debts<br />

1787: William Herschel discovers Titania and Oberon, moons of<br />

Uranus; Milan’s Teatro alla Scala is built by Giuseppe Piermarini<br />

(center); the Constitutional Convention convenes in Philadelphia<br />

(bottom); Morocco becomes the first country to recognize<br />

the United States as a sovereign nation; the Ottoman Empire<br />

declares war on Russia; Irish painter Robert Barker invents and<br />

patents the panorama; the first left and right shoes are made;<br />

Alexander Hamilton becomes the first U.S. Treasury secretary;<br />

the Constitution of the United States is completed and signed,<br />

going into effect on March 4; the first ships carrying convicts<br />

leave Great Britain for Australia’s Botany Bay<br />

(penal transports will continue until 1853)<br />

— The Editors<br />

October 2011 31

10-13 Mahler:Layout 1 10/3/11 11:38 AM Page 32<br />

distant Paris, with visits in Munich and Augsburg<br />

and a lengthy stay in Mannheim along<br />

the way. The composer’s father, Leopold, remained<br />

at home; the family could not subsist<br />

without the income he earned there. “The<br />

purpose of the journey,” Leopold reminded<br />

his son in a letter on November 27, “the sole<br />

purpose, was, is, and must be to obtain a position<br />

or earn some money.” Mozart failed to<br />

accomplish the former, although he claimed<br />

to have turned down a well-paying post as<br />

an organist at Versailles. In any case, the<br />

money he acquired from composing, performing,<br />

and teaching during his months<br />

away wouldn’t have been impressive even if<br />

he had been paid as promised for his engagements,<br />

which on numerous occasions<br />

he was not. Tragedy struck on July 3, 1778,<br />

when Mozart’s mother died as the result of a<br />

sudden illness. The 22-year-old composer<br />

(who had never before been without parental<br />

supervision) was left to make burial arrangements,<br />

break the news to his father and sister<br />

back home, and struggle on in a foreign<br />

country before making his way back to<br />

Salzburg, where he arrived in January 1779,<br />

dreading his return to the provincial routine<br />

he had hoped to escape.<br />

During the six months that Mozart had<br />

spent in Paris he made serious efforts to<br />

stake a place in that metropolis’s musical life.<br />

Immediately after his arrival on March 23,<br />

1778, he sought out an old family friend,<br />

Baron von Grimm, who had opened numerous<br />

Parisian doors when the Mozarts had<br />

visited Paris in 1763. The Baron again<br />

alerted his aristocratic circle, but the jobseeking<br />

adult Mozart was a harder sell than<br />

the seven-year-old prodigy had been, and he<br />

was received into Parisian salons with less<br />

excitement, if at all. Leopold, who in his barrage<br />

of correspondence proved to be a veritable<br />

Niagara of advice, reminded his son<br />

32<br />

New York Philharmonic<br />

Mozart and the Flute<br />

Mozart, 1789<br />

Much has been made of the fact that Mozart once<br />

spoke disparagingly of the flute. “I am quite inhibited<br />

when I have to compose for an instrument which I<br />

cannot endure,” he wrote to his father (from<br />

Mannheim on February 14, 1778, while on his way to<br />

Paris). It was the end of a litany of excuses<br />

explaining why he had not yet fulfilled a commission<br />

for some flute concertos (though he had found<br />

plenty of time to spend with his then girlfriend).<br />

This comment, clearly made in a snit, is often<br />

cited as proof that Mozart truly loathed the flute. It is<br />

weak evidence, especially since the composer never<br />

repeated anything to that effect in his remaining<br />

years, and since he would spotlight that instrument<br />

sensitively in many of his symphonies and operas, in<br />

addition to his two flute concertos (which he<br />

eventually did finish) and his four flute quartets, as<br />

well as the Flute and Harp Concerto. Would a<br />

composer who detested the flute have permitted it<br />

to serve as the “title character” of Die Zauberflöte<br />

(The Magic Flute), where it is exalted as a repository<br />

of mystical powers of salvation? In the end, the<br />

music would seem to put this question to rest. If<br />

Mozart really had misgivings about the instrument,<br />

listening to the concerto that he himself wrote for it<br />

would probably have converted him.<br />

(on April 20) to “be guided by the French<br />

taste” while in Paris (italics his). “If you only<br />

win applause and get a decent sum of<br />

money, let the devil take the rest.”

10-13 Mahler:Layout 1 10/3/11 11:38 AM Page 33<br />

Leopold was responding to a letter that his<br />

wife had sent him two weeks earlier that had<br />

reported that Wolfgang was already busy with<br />

several projects, among them “two concertos,<br />

one for the flute and the other for the harp.”<br />

She had it not quite right: it was one concerto<br />

for both instruments together, and in writing it<br />

Mozart was indeed taking his father’s advice<br />

about being guided by French taste, since the<br />

particular passion of French audiences just<br />

then was the symphonie concertante, effectively<br />

a concerto with multiple soloists.<br />

Mozart wrote the piece for a friend of<br />

Baron Grimm’s: the Duc de Guînes, an accomplished<br />

flutist whose daughter was receiving<br />

daily two-hour composition lessons<br />

from Mozart. As in much of Mozart’s music<br />

“in the French taste,” this concerto treads<br />

lightly in matters of harmonic bravery, but<br />

it makes up for that in its abundance of<br />

Angels and Muses<br />

melodic invention and the sheer sonic beauty<br />

of the instrumental combination. The concerto’s<br />

success was more aesthetic than pecuniary:<br />

by the end of July Mozart had still<br />

not been paid for the work; in addition, the<br />

duke tried to stiff him of half the money for<br />

his daughter’s lessons.<br />

Instrumentation: The Symphony No. 38<br />

employs two flutes, two oboes, two bassoons,<br />

two horns, two trumpets, timpani, and<br />

strings. The Concerto in C major for Flute<br />

and Harp calls for two oboes, two horns, and<br />

strings, in addition to the solo flute and harp.<br />

Cadenzas: As Mozart provided no cadenzas,<br />

though he calls for them in all three<br />

movements, the soloists in this performance<br />

of the Concerto for Flute and Harp play<br />

those crafted by Karl Hermann Pillney.<br />

Mozart composed his Flute and Harp Concerto on commission from Adrien-Louis de Bonnières de Souastre,<br />

Duc de Guînes (1735–1806). This music-loving aristocrat (who played the flute) had started life as a mere count,<br />

distinguished himself as a soldier in the Seven Years War, and served as French Ambassador to Berlin (where<br />

he had played flute duets with Frederick the Great) and to London (from whence he was recalled for financial<br />

improprieties). On returning to France, in 1776, he was elevated to the status of duke, and in 1788 was named<br />

Governor of Artois. On May 14, 1778, Mozart wrote to his father about the Duc de Guînes, “whose daughter is my<br />

pupil in composition, plays the flute extremely well, and … plays the harp magnifique.” He continued:<br />

She has a great deal of talent and even genius, and in particular a<br />

marvelous memory, so that she can play all her pieces,<br />

actually about 200, by heart. She is, however, extremely<br />

doubtful as to whether she has any talent for<br />

composition, especially as regards invention or<br />

ideas. But her father who, between ourselves, is<br />

somewhat too infatuated with her, declares that<br />

she certainly has ideas and that it is only that she<br />

is too bashful and has too little self-confidence.<br />

Well, we shall see. If she gets no inspiration or<br />

ideas (for at present she really has none<br />

whatever), then it is to no purpose, for — God<br />

knows — I can’t give her any. Her father’s intention<br />

is not to make a great composer of her. “She is not,”<br />

he said, “to compose operas, arias, concertos, sym pho -<br />

nies, but only grand sonatas for her instrument and mine.”<br />

The Concert, attributed to Jean-Honoré Fragonard<br />

October 2011<br />

33

10-13 Mahler:Layout 1 10/3/11 11:38 AM Page 34<br />

Jeux: Poème-dansé<br />

Ibéria, from Images for<br />

Orchestra<br />

Claude Debussy<br />

Claude Debussy developed a knotty relationship<br />

with the stage. He carried out work<br />

in each of the three principal stage genres:<br />

opera, ballet, and incidental music for plays.<br />

Yet he managed to complete only a single<br />

example of each — Pelléas et Mélisande,<br />

Jeux, and Le Martyre de Saint Sébastien, respectively,<br />

leaving numerous other attempts<br />

in various stages of incompletion. So far as<br />

ballet is concerned, he had essentially fulfilled<br />

a commission (between 1910 and<br />

1912) for a piece titled Khamma for the<br />

choreographer Maud Allan, though he left<br />

the orchestration to his fellow composer<br />

Charles Koechlin; but the piece never received<br />

even a concert performance until 1924 (six<br />

years after Debussy’s death) and did not<br />

reach the stage until<br />

1947. It remains largely<br />

unheard today. Two other<br />

ballet scores also remained<br />

incomplete: the<br />

children’s ballet La Boîte<br />

à joujoux of 1913 (which<br />

made it up to the orchestration<br />

stage), and<br />

No-ja-li (Le palais du silence)<br />

of 1913–14.<br />

In posterity, the score<br />

for Jeux (Games) has<br />

made up for the lack of<br />

the others. It is Debussy’s<br />

last completed<br />

orchestral work, and it<br />

has been cited as an essential<br />

point of departure<br />

for a certain strand<br />

34 New York Philharmonic<br />

In Short<br />

of later composers. Pierre Boulez maintained<br />

that it signified:<br />

the arrival of a kind of musical form which,<br />

renewing itself from moment to moment,<br />

implies a similarly instantaneous mode of<br />

perception.<br />

Debussy composed it for the impresario<br />

Serge Diaghilev, whose Ballets Russes —<br />

launched in Paris in 1909 — became quickly<br />

identified with the vanguard of the European<br />

arts scene. Diaghilev soon commissioned new<br />

ballet scores, of which the very first was<br />

Stravinsky’s Firebird, premiered in 1910. More<br />

Stravinsky followed, including Petrushka, premiered<br />

in 1911, and Le Sacre du printemps<br />

(The Rite of Spring) on May 29, 1913 — a<br />

date that earned legendary status thanks to<br />

the riot that broke out at its premiere. That<br />

event eclipsed the more minor disappointment<br />

that precisely two weeks earlier had attended<br />

the premiere of Jeux, with a score by Debussy.<br />

Born: August 22, 1862, in St. Germain-en-Laye, just outside Paris, France<br />

Died: March 25, 1918, in Paris<br />

Works composed and premiered: Jeux: composed 1912–13, but largely in<br />

August 1913; premiered May 15, 1913, in a staged production by the Ballets<br />

Russes at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, Pierre Monteux, conductor; it was<br />

given the following year in concert form by the Orchestre des Concerts Colonne,<br />

conducted by Gabriel Pierné.<br />

Ibéria: begun in 1905 as a piano duet; completed as an orchestral work on<br />

December 25, 1908; premiered February 20, 1910, Gabriel Pierné conducting<br />

the Orchestre des Concerts Colonne in Paris<br />

New York Philharmonic premieres and most recent performances:<br />

Jeux: premiered January 13, 1938, Georges Enesco, conductor; most recently<br />

performed March 18, 1986, Pierre Boulez, conductor<br />

Ibéria: premiered January 3, 1911, Gustav Mahler, conductor; most recently<br />

performed February 13, 2007, Alan Gilbert, conductor<br />

Estimated durations: Jeux: ca. 18 minutes; Ibéria: ca. 20 minutes

10-13 Mahler:Layout 1 10/3/11 11:38 AM Page 35<br />

The concept of Jeux was expounded by<br />

the dancer Vaslav Nijinsky over lunch with<br />

Diaghilev and the designer Léon Bakst at<br />

the Savoy Hotel in London, the notes being<br />

jotted down on the tablecloth. The event was<br />

recounted to the painter Jacques-Émile<br />

Blanche, who, in his memoirs, related the scenario<br />

drawn up on that occasion:<br />

There should be no corps de ballet, no ensembles,<br />

no variations, no pas de deux,<br />

only boys and girls in flannels and rhythmic<br />

movement. A group at a certain stage was<br />

to depict a fountain, and a game of tennis<br />

was to be interrupted by the crashing of<br />

an aeroplane.<br />

Nijinsky also detailed this work’s genesis<br />

in his diary, adding the detail that the action<br />

would depict the story of “three young men<br />

making love to each other.” It fell to Blanche<br />

to telegraph the concept to Debussy. The<br />

composer immediately responded “I should<br />

not dream of writing a score for this work,”<br />

but then amended his answer to say that he<br />

could find a way to write it after all, if his fee<br />

were to be doubled.<br />

In the end, the plane crash was blessedly<br />

eliminated and the three young men Nijinsky<br />

imagined were turned into one young man and<br />

two young women. Nijinsky ended up falling<br />

out of love with the project, but Debussy seems<br />

to have warmed to it, producing his score with<br />

uncharacteristic speed, apparently within the<br />

course of about three weeks in August 1913.<br />

Near the end of the month he wrote to his<br />

friend, the composer André Caplet:<br />

How was I able to forget the cares of this<br />

world and manage to write music that is<br />

nevertheless joyous and alive with droll<br />

rhythms? Nature, so absurdly harsh, sometimes<br />

takes pity, it seems, on her children.<br />

Sources and Inspirations<br />

Nijinsky’s initial inspirations for the ballet Jeux<br />

underwent a considerable amount of refinement,<br />

eventually yielding this scenario, which was supplied<br />

to Debussy as the foundation on which he should<br />

construct his score:<br />

In a park, at dusk, a tennis ball goes astray; a<br />

young man, then two young women hurriedly try to<br />

find it. The artificial light of huge electric lamps<br />

casts its fantastic gleam about them and suggests<br />

the idea of children’s games; they play hide-andseek,<br />

run after each other, quarrel and sulk for no<br />

good reason; the night is warm, the sky bathed in<br />

gentle light, they kiss. But the spell is broken by a<br />

tennis ball thrown by some malicious hand. Surprised<br />

and frightened, the young man and two<br />

young women disappear into the depths of the<br />

night-enshrouded park.<br />

Nonetheless, Debussy hated Nijinsky’s<br />

choreography and he was glad to be rid of the<br />

ballet, which was poorly received. While the<br />

performance was underway on opening night,<br />

he left his box to smoke a cigarette outside.<br />

Almost 10 years earlier the final work on this<br />

program, Ibéria,, had been premiered. The<br />

Spanish composer Manuel de Falla wrote in<br />

an article he contributed to an all-Debussy<br />

issue of the Revue musicale, published in<br />

December 1920:<br />

Without knowing Spain, or without having<br />

set foot on Spanish ground, Claude Debussy<br />

has written Spanish music. He came<br />

to know Spain through books and paintings,<br />

through songs and dances performed<br />

by native Spaniards.<br />

He continued, replete with admiration:<br />

Debussy, who did not actually know Spain,<br />

spontaneously — I dare say unconsciously —<br />

October 2011<br />

35

10-13 Mahler:Layout 1 10/3/11 11:38 AM Page 36<br />

Debussy in May 1902<br />

In the Composer’s Words<br />

Debussy may have insisted that IIbbéérriiaa was not based<br />

on any plot or program, but in a letter to his colleague<br />

André Caplet, written six days after the work’s premiere,<br />

he revealed just how specific his imagery was:<br />

You can’t imagine how naturally the transition works<br />

between Parfumes of the Night and Morning of a<br />

Festival Day. It sounds as though it’s improvised. …<br />

The way it comes to life, with people and things<br />

waking up ….. There’s a man selling watermelons<br />

and urchins whistling: I see them all quite clearly.<br />

created such Spanish music as was to<br />

arouse the envy of many who knew Spain<br />

only too well. He crossed the border only<br />

once, and stayed for a few hours in San Sebastián<br />

to attend a bullfight: little enough<br />

experience indeed. However, he kept a vivid<br />

memory of the unique light in the bullring, of<br />

the astonishing contrast between the side<br />

flooded by sunlight and the one in shadow.<br />

Perhaps an evocation of that afternoon<br />

passed on Spain’s threshold is to be found<br />

in Morning of a Festival Day from Ibéria.<br />

Debussy’s Spain, then, was a romantic<br />

Spain born of fantasy. It was an imaginary<br />

journey the composer would take often and<br />

would inspire a number of compositions.<br />

Some proclaimed their Spanish connection<br />

explicitly, such as his piano piece La Soirée<br />

dans Grenade (from Estampes), while others<br />

36 New York Philharmonic<br />

reflected it more subtly through the specific<br />

sounds of their music, as when the string<br />

players mimic the strumming of a guitar in<br />

the second movement of his String Quartet.<br />

Falla applauded Debussy’s achievements<br />

as revelatory for Spanish composers themselves.<br />

“While the Spanish composer to a<br />

large extent uses in his music the authentic<br />

popular material,” Falla wrote,<br />

the French master avoids them and creates a<br />

music of his own, borrowing only the essence<br />

of its fundamental elements. There is still another<br />

interesting fact regarding the particular<br />

texture of Debussy’s music. In Andalusia they<br />

are produced on the guitar in the most spontaneous<br />

way. It is curious that Spanish composers<br />

have neglected, even despised as<br />

barbaric, those effects, or they have adapted<br />

them to the old musical procedures. Debussy<br />

has taught the way to use them.<br />

Ibéria is the most imposing of Debussy’s<br />

imaginary “postcards from Spain,” occupying<br />

three full movements for a colorfully constituted<br />

orchestra, themselves the central<br />

group of the composer’s symphonic triptych<br />

Images. (Although Debussy titled the set only<br />

Images, it is commonly referred to as Images<br />

for Orchestra to distinguish it from his two<br />

earlier sets of Images for piano.) The three<br />

Images for Orchestra drew on national music<br />

from different lands — the first part, Gigues,<br />

evokes English folk dance; the third, Rondes<br />

de printemps, portrays an Italian May Day<br />

celebration — and as a whole they occupied<br />

him for some eight years. He began Ibéria in<br />

1905 and by the following July reported to<br />

his publisher that he expected to complete it<br />

by the next week. Two and a half years later<br />

he finally did finish it, and by that time what<br />

he had envisioned as a work for piano duet<br />

had grown into a score for full orchestra.

10-13 Mahler:Layout 1 10/3/11 11:38 AM Page 37<br />

“It is useless to ask me for anecdotes about<br />

this work,” Debussy protested to the exasperated<br />

program annotator charged with producing<br />

materials to accompany the premiere of<br />

Ibéria, in 1910. “There is no story attached to<br />

it, and I depend on the music alone to arouse<br />

the interest of the public.” Even if Ibéria has<br />

no extramusical plot, the scenes it evokes are<br />

nonetheless specific. The first movement is a<br />

street scene, its brilliant light thrown into<br />

greater relief by the shadowy contrast heard<br />

midway. Mystery pervades the night air in the<br />

second movement. And the third, which follows<br />

without pause, vividly portrays a festival.<br />

Sources and Inspirations<br />

Instrumentation: Jeux calls for two flutes<br />

and two piccolos, three oboes and English<br />

horn, three clarinets and bass clarinet, three<br />

bassoons and contrabassoon, four horns,<br />

four trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani,<br />

tambourine, triangle, cymbals, xylophone,<br />

celesta, two harps, and strings. Ibéria<br />

employs three flutes (one doubling piccolo)<br />

and piccolo, two oboes and English horn,<br />

three clarinets, three bassoons and contrabassoon,<br />

four horns, three trumpets, three<br />

trombones, tuba, timpani, tambourine, castanets,<br />

snare drum, xylophone, chimes, two<br />

harps, celesta, and strings.<br />

The three pieces of Debussy’s Images evoke three different cultures: Gigues points to England, with its use of<br />

the Northumbrian folk song “The Keel Row,” and Rondes du printemps draws on two French folk songs, “Nous<br />

n’irons plus au bois,” and “Do, l’enfant, do.” IIbbéérriiaa contains no specific national musical references to Spain, but<br />

a Spanish feeling can surely be felt throughout it, so much so that it could surprise a listener to learn that Debussy<br />

had never spent any significant time in that country. The Spanish composer Manual de Falla inferred that<br />

his French colleague had learned the sights, sounds, scents, and sense of Spain through the art created by<br />

Spaniards, such as Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida (1863–1923).<br />

— The Editors<br />

Sorolla’s Beach at Valencia or Afternoon Sun, 1908<br />

October 2011<br />

37

10-13 Mahler:Layout 1 10/3/11 11:38 AM Page 38<br />

New York Philharmonic<br />

2011–2012 SEASON<br />

ALAN GILBERT, Music Director, The Yoko Nagae Ceschina Chair<br />

Case Scaglione, Assistant Conductor<br />

Joshua Weilerstein, Assistant Conductor<br />

Leonard Bernstein, Laureate Conductor, 1943–1990<br />

Kurt Masur, Music Director Emeritus<br />

VIOLINS<br />

Glenn Dicterow<br />

Concertmaster<br />

The Charles E. Culpeper<br />

Chair<br />

Sheryl Staples<br />

Principal Associate<br />

Concertmaster<br />

The Elizabeth G. Beinecke<br />

Chair<br />

Michelle Kim<br />

Assistant Concertmaster<br />

The William Petschek<br />

Family Chair<br />

Enrico Di Cecco<br />

Carol Webb<br />

Yoko Takebe<br />

Hae-Young Ham<br />

The Mr. and Mrs. Timothy<br />

M. George Chair<br />

Lisa GiHae Kim<br />

Kuan-Cheng Lu<br />

Newton Mansfield<br />

The Edward and Priscilla<br />

Pilcher Chair<br />

Kerry McDermott<br />

Anna Rabinova<br />

Charles Rex<br />

The Shirley Bacot Shamel<br />

Chair<br />

Fiona Simon<br />

Sharon Yamada<br />

Elizabeth Zeltser<br />

The William and Elfriede<br />

Ulrich Chair<br />

Yulia Ziskel<br />

Marc Ginsberg<br />

Principal<br />

Lisa Kim*<br />

In Memory of Laura Mitchell<br />

Soohyun Kwon<br />

The Joan and Joel I. Picket<br />

Chair<br />

Duoming Ba<br />

38 New York Philharmonic<br />

Marilyn Dubow<br />

The Sue and Eugene<br />

Mercy, Jr. Chair<br />

Martin Eshelman<br />

Quan Ge<br />

The Gary W. Parr Chair<br />

Judith Ginsberg<br />

Stephanie Jeong+<br />

Hanna Lachert<br />

Hyunju Lee<br />

Joo Young Oh<br />

Daniel Reed<br />

Mark Schmoockler<br />

Na Sun<br />

Vladimir Tsypin<br />

VIOLAS<br />

Cynthia Phelps<br />

Principal<br />

The Mr. and Mrs. Frederick<br />

P. Rose Chair<br />

Rebecca Young*<br />

Irene Breslaw**<br />

The Norma and Lloyd<br />

Chazen Chair<br />

Dorian Rence<br />

Katherine Greene<br />

The Mr. and Mrs. William J.<br />

McDonough Chair<br />

Dawn Hannay<br />

Vivek Kamath<br />

Peter Kenote<br />

Kenneth Mirkin<br />

Judith Nelson<br />

Robert Rinehart<br />

The Mr. and Mrs. G. Chris<br />

Andersen Chair<br />

CELLOS<br />

Carter Brey<br />

Principal<br />

The Fan Fox and Leslie R.<br />

Samuels Chair<br />

Eileen Moon*<br />

The Paul and Diane<br />

Guenther Chair<br />

Eric Bartlett<br />

The Shirley and Jon<br />

Brodsky Foundation Chair<br />

Maria Kitsopoulos<br />

Elizabeth Dyson<br />

The Mr. and Mrs. James E.<br />

Buckman Chair<br />

Sumire Kudo<br />

Qiang Tu<br />

Ru-Pei Yeh<br />

The Credit Suisse Chair<br />

in honor of Paul Calello<br />

Wei Yu<br />

Wilhelmina Smith++<br />

BASSES<br />

Timothy Cobb++<br />

Acting Principal<br />

The Redfield D. Beckwith<br />

Chair<br />

Orin O’Brien*<br />

Acting Associate Principal<br />

The Herbert M. Citrin Chair<br />

William Blossom<br />

The Ludmila S. and Carl B.<br />

Hess Chair<br />

Randall Butler<br />

David J. Grossman<br />

Satoshi Okamoto<br />

FLUTES<br />

Robert Langevin<br />

Principal<br />

The Lila Acheson Wallace<br />

Chair<br />

Sandra Church*<br />

Mindy Kaufman<br />

PICCOLO<br />

Mindy Kaufman<br />

OBOES<br />

Liang Wang<br />

Principal<br />

The Alice Tully Chair<br />

Sherry Sylar*<br />

Robert Botti<br />

The Lizabeth and Frank<br />

Newman Chair<br />

ENGLISH HORN<br />

The Joan and Joel Smilow<br />

Chair<br />

CLARINETS<br />

Mark Nuccio<br />

Acting Principal<br />

The Edna and W. Van Alan<br />

Clark Chair<br />

Pascual Martinez<br />

Forteza*<br />

Acting Associate Principal<br />

The Honey M. Kurtz Family<br />

Chair<br />

Alucia Scalzo++<br />

Amy Zoloto++<br />

E-FLAT CLARINET<br />

Pascual Martinez<br />

Forteza<br />

BASS CLARINET<br />

Amy Zoloto++<br />

BASSOONS<br />

Judith LeClair<br />

Principal<br />

The Pels Family Chair<br />

Kim Laskowski*<br />

Roger Nye<br />

Arlen Fast<br />

CONTRABASSOON<br />

Arlen Fast

10-13 Mahler:Layout 1 10/3/11 11:38 AM Page 39<br />

HORNS<br />

Philip Myers<br />

Principal<br />

The Ruth F. and Alan J. Broder Chair<br />

Stewart Rose++*<br />

Acting Associate Principal<br />

Cara Kizer Aneff<br />

R. Allen Spanjer<br />

Howard Wall<br />

David Smith++<br />

TRUMPETS<br />

Philip Smith<br />

Principal<br />

The Paula Levin Chair<br />

Matthew Muckey*<br />

Ethan Bensdorf<br />

Thomas V. Smith<br />

TROMBONES<br />

Joseph Alessi<br />

Principal<br />

The Gurnee F. and Marjorie L. Hart<br />

Chair<br />

Daniele Morandini*<br />

Acting Associate Principal<br />

David Finlayson<br />

The Donna and Benjamin M. Rosen<br />

Chair<br />

BASS TROMBONE<br />

James Markey<br />

The Daria L. and William C. Foster<br />

Chair<br />

TUBA<br />

Alan Baer<br />

Principal<br />

TIMPANI<br />

Markus Rhoten<br />

Principal<br />

The Carlos Moseley Chair<br />

Kyle Zerna**<br />

PERCUSSION<br />

Christopher S. Lamb<br />

Principal<br />

The Constance R. Hoguet Friends of<br />

the Philharmonic Chair<br />

Daniel Druckman*<br />

The Mr. and Mrs. Ronald J. Ulrich<br />

Chair<br />

Kyle Zerna<br />

HARP<br />

Nancy Allen<br />

Principal<br />

The Mr. and Mrs. William T. Knight III<br />

Chair<br />

KEYBOARD<br />

In Memory of Paul Jacobs<br />

HARPSICHORD<br />

Lionel Party<br />

PIANO<br />

The Karen and Richard S. LeFrak<br />

Chair<br />

Harriet Wingreen<br />

Jonathan Feldman<br />

ORGAN<br />

Kent Tritle<br />

LIBRARIANS<br />

Lawrence Tarlow<br />

Principal<br />

Sandra Pearson**<br />

Sara Griffin**<br />

ORCHESTRA PERSONNEL<br />

MANAGER<br />

Carl R. Schiebler<br />

STAGE REPRESENTATIVE<br />

Louis J. Patalano<br />

AUDIO DIRECTOR<br />

Lawrence Rock<br />

* Associate Principal<br />

** Assistant Principal<br />

+ On Leave<br />

++ Replacement/Extra<br />

The New York Philharmonic uses<br />

the revolving seating method for<br />

section string players who are<br />

listed alpha betically in the roster.<br />

HONORARY MEMBERS OF THE<br />

SOCIETY<br />

Emanuel Ax<br />

Pierre Boulez<br />

Stanley Drucker<br />

Lorin Maazel<br />

Zubin Mehta<br />

Carlos Moseley<br />

Instruments made possible, in part, by<br />

The Richard S. and Karen<br />

LeFrak Endowment Fund.<br />

Programs are supported, in part, by<br />

public funds from the New York<br />

City Department of Cultural<br />

Affairs, New York State Council<br />

on the Arts, and the National<br />

Endowment for the Arts.<br />

Steinway is the Official Piano of<br />

the New York Philharmonic and<br />

Avery Fisher Hall.<br />

October 2011<br />

39

10-13 Mahler:Layout 1 10/3/11 11:38 AM Page 40<br />

The Artists<br />

Lorin Maazel served as Music Director of<br />

the New York Philharmonic from 2002 to<br />

2009. In the 2010–11 season he completed<br />

his fifth and final year as the inaugural music<br />

director of the Palau de les Arts Reina Sofia<br />

opera house in Valencia, Spain, and at the<br />

start of the 2012–13 season he will become<br />

music director of the Munich Philharmonic.<br />

Mr. Maazel is also the founder and artistic director<br />

of the Castleton Festival, based on his<br />

farm property in Virginia, which was launched<br />

to great acclaim in 2009. The festival is expanding<br />

its activities nationally and internationally<br />

in 2011 and beyond.<br />

Mr. Maazel is also a composer, with a<br />

wide-ranging catalogue of works written primarily<br />

over the last dozen years. His first<br />

opera, 1984, based on George Orwell’s literary<br />

masterpiece, had its world premiere at<br />

the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, in<br />

May 2005, and was revived at Milan’s Teatro<br />

40 New York Philharmonic<br />

alla Scala in May 2008. A Decca DVD of the<br />

original London production was released in<br />

May 2008.<br />

A second-generation American born in<br />

Paris, France, Lorin Maazel began violin lessons<br />

at age five, and conducting lessons at<br />

age seven. He studied with Vladimir Baka -<br />

leinikoff, and appeared publicly for the first<br />

time at age eight. Between ages nine and fifteen<br />

he conducted most of the major American<br />

orchestras, including the NBC Symphony<br />

at the invitation of Arturo Toscanini. In the<br />

course of his decades-long career Mr. Maazel<br />

has conducted more than 150 orchestras in<br />

no fewer than 5,000 opera and concert performances.<br />

He has made more than 300<br />

recordings, including symphonic cycles of<br />

complete orchestral works by Beethoven,<br />

Brahms, Debussy, Mahler, Schubert, Tchai -<br />

kovsky, Rachmaninoff, and Richard Strauss,<br />

winning 10 Grands Prix du Disques.<br />

Lorin Maazel has been music director of<br />

the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra<br />

(1993–2002); music director of the Pittsburgh<br />

Symphony (1988–96); general manager<br />

and chief conductor of the Vienna<br />

Staatsoper (1982–84, the first American to<br />

hold that position); music director of The<br />

Cleveland Orchestra (1972–82); and artistic<br />

director and chief conductor of the Deutsche<br />

Oper Berlin (1965–71). His close association<br />

with the Vienna Philharmonic has included<br />

11 internationally televised New<br />

Year’s Concerts from Vienna.

10-13 Mahler:Layout 1 10/3/11 11:38 AM Page 41<br />

Robert Langevin joined the New York Philharmonic<br />

as Principal Flute, The Lila Acheson<br />

Wallace Chair, in the 2000–01 season. In May<br />

2001 he made his solo debut with the Orchestra<br />

in the U.S. premiere of Siegfried<br />

Matthus’s Concerto for Flute and Harp with<br />

Philharmonic Principal Harp Nancy Allen, led<br />

by then Music Director Kurt Masur. Prior to the<br />

Philharmonic, Mr. Langevin held the Jackman<br />

Pfouts Principal Flute Chair of the Pittsburgh<br />

Symphony, was an adjunct professor at<br />

Duquesne University in Pittsburgh, and served<br />

as associate principal of the Montreal Symphony<br />

Orchestra for 13 years. As a member<br />

of Musica Camerata Montreal and l’Ensemble<br />

de la Société de Musique Contemporaine du<br />

Québec, he premiered many works, including<br />

the Canadian premiere of Pierre Boulez’s Le<br />

Marteau sans maître. In addition, Mr. Langevin<br />

has performed as soloist with Quebec’s most<br />

distinguished ensembles and has recorded<br />

many recitals and chamber music programs<br />

for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation.<br />

He also served on the faculty of the University<br />

of Montreal for nine years.<br />

Born in Sherbrooke, Quebec, Robert<br />

Langevin won the prestigious Prix d’Europe, a<br />

national competition open to all instruments<br />

with a first prize of a two-year scholarship to<br />

study in Europe. He subsequently worked<br />

with Aurèle Nicolet at the Staatliche<br />

Hochschule für Musik in Freiburg, Germany,<br />

from which he graduated in 1979. He also<br />

studied with Maxence Larrieu in Geneva, winning<br />

second prize at the Budapest International<br />

Competition in 1980. Robert Langevin is a<br />

member of the Philharmonic Quintet of New<br />

York, and has given recitals and master classes<br />

throughout the United States and abroad.<br />

Nancy Allen joined the New York Philharmonic<br />

in June 1999 as Principal Harp, The<br />

Mr. and Mrs. William T. Knight III Chair. She<br />

maintains a busy international concert schedule<br />

as well as heading the harp departments of<br />

The Juilliard School and the Aspen Music Festival<br />

and School. In addition, Ms. Allen appears<br />

regularly with The Chamber Music Society of<br />

Lincoln Center and the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra.<br />

In May 2001 she was featured in the<br />

Philharmonic’s U.S. premiere of Siegfried<br />

Matthus’s Concerto for Flute and Harp with<br />

then Music Director Kurt Masur and Principal<br />

Flute Robert Langevin.<br />

Ms. Allen’s performing schedule includes<br />

solo appearances at major international festivals,<br />

and has featured collaborations with soprano<br />

Kathleen Battle, clarinetist Richard<br />

Stoltzman, and guitarist Manuel Barrueco; and<br />

with flutist Carol Wincenc and Philharmonic<br />

Principal Viola Cynthia Phelps in their trio, Les<br />

October 2011<br />

41

10-13 Mahler:Layout 1 10/3/11 11:38 AM Page 42<br />

Amies. She has appeared on PBS’s Live From<br />

Lincoln Center with The Chamber Music Society<br />

of Lincoln Center, as well as with Ms. Battle,<br />

and has performed as a recitalist on “Music<br />

at the Supreme Court” in Washington, D.C. Ms.<br />

Allen’s recording of Ravel’s Introduction and<br />

Allegro with the Tokyo String Quartet, flutist<br />

Ransom Wilson, and clarinetist David Shifrin<br />

42 New York Philharmonic<br />

received a Grammy Award nomination; she can<br />

also be heard on recordings on the Sony Classical,<br />

Deutsche Grammophon, and CRI labels.<br />

Nancy Allen studied with Marcel Grandjany<br />

at The Juilliard School. She won the<br />

Fifth International Harp Competition in Israel,<br />

and was awarded a National Endowment for<br />

the Arts Solo Recitalist Award.

10-13 Mahler:Layout 1 10/3/11 11:38 AM Page 43<br />

New York Philharmonic<br />

The New York Philharmonic, founded in 1842<br />

by a group of local musicians led by Americanborn<br />

Ureli Corelli Hill, is by far the oldest symphony<br />

orchestra in the United States, and one of<br />

the oldest in the world. It plays some 180 concerts<br />

a year, and on May 5, 2010, gave its<br />

15,000th concert — a milestone unmatched by<br />

any other symphony orchestra in the world.<br />

Music Director Alan Gilbert, The Yoko Nagae<br />

Ceschina Chair, began his tenure in September<br />

2009, the latest in a distinguished line of 20thcentury<br />

musical giants that has included Lorin<br />

Maazel (2002–09); Kurt Masur (Music Director<br />

1991–2002, Music Director Emeritus since<br />

2002); Zubin Mehta (1978–91); Pierre Boulez<br />

(1971–77); and Leonard Bernstein (appointed<br />

Music Director in 1958; given the lifetime title of<br />

Laureate Conductor in 1969).<br />

Since its inception the Orchestra has championed<br />

the new music of its time, commissioning<br />

and/or premiering many important works, such<br />

as Dvorˇák’s Symphony No. 9, From the New<br />

World; Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 3;<br />

Gershwin’s Piano Concerto in F; and Copland’s<br />

Connotations. The Philharmonic has also given<br />

the U.S. premieres of such works as Beethoven’s<br />

Symphonies Nos. 8 and 9 and Brahms’s Symphony<br />

No. 4. This pioneering tradition has continued<br />

to the present day, with works of major<br />

contemporary composers regularly scheduled<br />

each season, including John Adams’s Pulitzer<br />

Prize– and Grammy Award–winning On the<br />

Transmigration of Souls; Melinda Wagner’s Trombone<br />

Concerto; Esa-Pekka Salonen’s Piano Concerto;<br />

Magnus Lindberg’s EXPO and Al largo;<br />

Wynton Marsalis’s Swing Symphony (Symphony<br />

No. 3); Christopher Rouse’s Odna Zhizn; and, by<br />

the end of the 2010–11 season, 11 works in<br />

CONTACT!, the new-music series.<br />

The roster of composers and conductors who<br />

have led the Philharmonic includes such historic<br />

figures as Theodore Thomas, Antonín Dvorˇák,<br />

Gustav Mahler (music director 1909–11), Otto<br />

Klemperer, Richard Strauss, Willem Mengelberg<br />

(Music Director 1922–30), Wilhelm Furtwängler,<br />

Arturo Toscanini (Music Director 1928–36), Igor<br />

Stravinsky, Aaron Copland, Bruno Walter (Music<br />

Advisor 1947–49), Dimitri Mitropoulos (Music Director<br />

1949–58), Klaus Tennstedt, George Szell<br />

(Music Advisor 1969–70), and Erich Leinsdorf.<br />

Long a leader in American musical life, the Philharmonic<br />

has become renowned around the<br />

globe, appearing in 430 cities in 63 countries on<br />

5 continents. Under Alan Gilbert’s leadership, the<br />

Orchestra made its Vietnam debut at the Hanoi<br />

Opera House in October 2009. In February 2008<br />

the Philharmonic, conducted by then Music Director<br />

Lorin Maazel, gave a historic performance<br />

in Pyongyang, D.P.R.K., earning the 2008 Common<br />

Ground Award for Cultural Diplomacy. In<br />

2012 the Philharmonic becomes an International<br />

Associate of London’s Barbican Centre.<br />

The Philharmonic has long been a media pioneer,<br />

having begun radio broadcasts in 1922, and<br />

is currently represented by The New York Philharmonic<br />

This Week — syndicated nationally and<br />

internationally 52 weeks per year, and available<br />

at nyphil.org. It continues its television presence<br />

on Live From Lincoln Center on PBS, and in<br />

2003 made history as the first symphony orchestra<br />

ever to perform live on the Grammy Awards.<br />

Since 1917 the Philharmonic has made nearly<br />

2,000 recordings, and in 2004 became the first<br />

major American orchestra to offer <strong>download</strong>able<br />

concerts, recorded live. Since June 2009 more<br />

than 50 concerts have been released as <strong>download</strong>s,<br />

and the Philharmonic’s self-produced<br />

recordings will continue with Alan Gilbert and the<br />

New York Philharmonic: 2011–12 Season, comprising<br />

12 releases. Famous for its long-running<br />

Young People’s Concerts, the Philharmonic has developed<br />

a wide range of educational programs,<br />

among them the School Partnership Program that<br />

enriches music education in New York City, and<br />

Learning Overtures, which fosters international exchange<br />

among educators.<br />

Credit Suisse is the Global Sponsor of the New<br />

York Philharmonic.<br />

October 2011<br />

43

10-13 Mahler:Layout 1 10/3/11 11:38 AM Page 44<br />

The Music Director<br />

Music Director Alan Gilbert, The Yoko<br />

Nagae Ceschina Chair, began his tenure at<br />

the New York Philharmonic in September<br />

2009, launching what New York magazine<br />

called “a fresh future for the Philharmonic.”<br />

His creative approach to programming combines<br />

works in fresh and innovative ways,<br />

and he has developed artistic partnerships,<br />

including the positions of The Marie-Josée<br />

Kravis Composer-in-Residence and The Mary<br />

and James G. Wallach Artist-in-Residence; an<br />

annual three-week festival; and CONTACT!,<br />

the new-music series. The first native New<br />

Yorker to hold the post, he has sought to<br />

make the Orchestra a point of civic pride for<br />

the city as well as for the country.<br />

In the 2011–12 season Alan Gilbert conducts<br />

world premieres, three Mahler symphonies,<br />

a residency at London’s Barbican<br />

Centre, tours to Europe and California, and a<br />

season-concluding musical exploration of<br />

space that features Stockhausen’s theatrical<br />

immersion, Gruppen, to be given at the Park<br />

Avenue Armory. Highlights of the previous<br />

season include two tours of European music<br />

capitals, Carnegie Hall’s 120th Anni versary<br />

44 New York Philharmonic<br />

Concert, and an acclaimed production of<br />

Janáček’s The Cunning Little Vixen, hailed<br />

by The Washington Post as “another victory,”<br />

building on 2010’s wildly successful staging<br />

of Ligeti’s Le Grand Macabre, which The New<br />

York Times called “an instant Philharmonic<br />

milestone.” Other highlights of Mr. Gilbert’s inaugural<br />

season comprise the Asian Horizons<br />

tour in October 2009, which included the Orchestra’s<br />

Vietnam debut at the historic Hanoi<br />

Opera House; the EUROPE / WINTER<br />

2010 tour; world premieres; and chamber<br />

performances as violinist and violist with Philharmonic<br />

musicians.<br />

In September 2011 Alan Gilbert became<br />

Director of Conducting and Orchestral Studies<br />

at The Juilliard School, where he is also<br />

the first to hold the William Schuman Chair in<br />

Musical Studies. He is Conductor Laureate of<br />

the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra<br />

and Principal Guest Conductor of Hamburg’s<br />

NDR Symphony Orchestra; he regularly conducts<br />

leading orchestras in the U.S. and<br />

abroad. His 2011–12 season engagements<br />

include appearances with the Munich Philharmonic,<br />

San Francisco Symphony, Cleveland<br />

Orchestra, Orchestre Philharmonique de<br />

Radio France, Royal Swedish Opera, and the<br />

Royal Stockholm Philharmonic.<br />

Alan Gilbert made his acclaimed Metropolitan<br />

Opera debut in November 2008 leading<br />

John Adams’s Doctor Atomic. His recordings<br />

have been nominated for Grammy Awards,<br />

and his recording of Mahler’s Symphony No. 9<br />

received top honors from the Chicago Tribune<br />

and Gramophone magazine. Mr. Gilbert<br />

studied at Harvard University, The Curtis Institute<br />

of Music, and The Juilliard School, and<br />

served as the assistant conductor of The<br />

Cleveland Orchestra (1995–97). In May 2010<br />

he received an Honorary Doctor of Music degree<br />

from The Curtis Institute of Music.

10-13 Mahler:Layout 1 10/3/11 11:38 AM Page 45<br />

LGOs<br />

October 2011<br />

45

10-13 Mahler:Layout 1 10/3/11 11:38 AM Page 46<br />

LGOs<br />

46 New York Philharmonic