Graduate Recital: Program Notes - InstantEncore

Graduate Recital: Program Notes - InstantEncore

Graduate Recital: Program Notes - InstantEncore

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

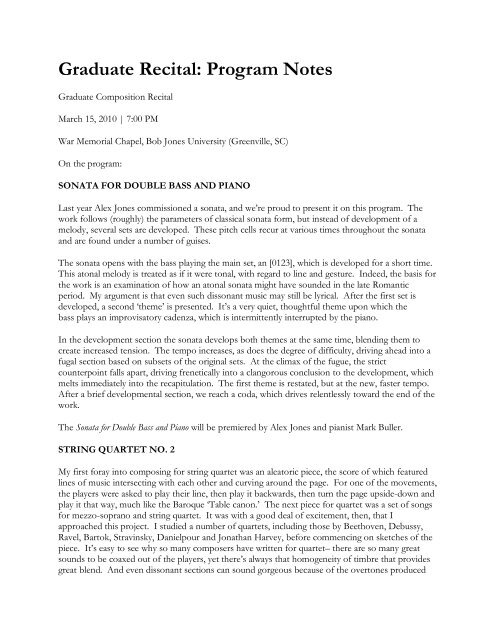

<strong>Graduate</strong> <strong>Recital</strong>: <strong>Program</strong> <strong>Notes</strong><br />

<strong>Graduate</strong> Composition <strong>Recital</strong><br />

March 15, 2010 | 7:00 PM<br />

War Memorial Chapel, Bob Jones University (Greenville, SC)<br />

On the program:<br />

SONATA FOR DOUBLE BASS AND PIANO<br />

Last year Alex Jones commissioned a sonata, and we’re proud to present it on this program. The<br />

work follows (roughly) the parameters of classical sonata form, but instead of development of a<br />

melody, several sets are developed. These pitch cells recur at various times throughout the sonata<br />

and are found under a number of guises.<br />

The sonata opens with the bass playing the main set, an [0123], which is developed for a short time.<br />

This atonal melody is treated as if it were tonal, with regard to line and gesture. Indeed, the basis for<br />

the work is an examination of how an atonal sonata might have sounded in the late Romantic<br />

period. My argument is that even such dissonant music may still be lyrical. After the first set is<br />

developed, a second ‘theme’ is presented. It’s a very quiet, thoughtful theme upon which the<br />

bass plays an improvisatory cadenza, which is intermittently interrupted by the piano.<br />

In the development section the sonata develops both themes at the same time, blending them to<br />

create increased tension. The tempo increases, as does the degree of difficulty, driving ahead into a<br />

fugal section based on subsets of the original sets. At the climax of the fugue, the strict<br />

counterpoint falls apart, driving frenetically into a clangorous conclusion to the development, which<br />

melts immediately into the recapitulation. The first theme is restated, but at the new, faster tempo.<br />

After a brief developmental section, we reach a coda, which drives relentlessly toward the end of the<br />

work.<br />

The Sonata for Double Bass and Piano will be premiered by Alex Jones and pianist Mark Buller.<br />

STRING QUARTET NO. 2<br />

My first foray into composing for string quartet was an aleatoric piece, the score of which featured<br />

lines of music intersecting with each other and curving around the page. For one of the movements,<br />

the players were asked to play their line, then play it backwards, then turn the page upside-down and<br />

play it that way, much like the Baroque ‘Table canon.’ The next piece for quartet was a set of songs<br />

for mezzo-soprano and string quartet. It was with a good deal of excitement, then, that I<br />

approached this project. I studied a number of quartets, including those by Beethoven, Debussy,<br />

Ravel, Bartok, Stravinsky, Danielpour and Jonathan Harvey, before commencing on sketches of the<br />

piece. It’s easy to see why so many composers have written for quartet– there are so many great<br />

sounds to be coaxed out of the players, yet there’s always that homogeneity of timbre that provides<br />

great blend. And even dissonant sections can sound gorgeous because of the overtones produced

y the instruments — listen, for example, to the Harvey quartets, which at times are microtonal, and<br />

still there’s that underlying sense of lushness and beauty that holds sway.<br />

The Second String Quartet is in three movements. The first is ‘Aria,’ which begins with a simple E<br />

major chord. One by one, instruments take turns coming out of the texture and ’singing’ their line<br />

to the accompaniment underneath. As the players increasingly embark on solo lines, the<br />

accompaniment ceases to exist, and we’re left with a confusing mixture of four independent lines.<br />

This climax gradually settles back down to the opening E major chord.<br />

The second movement is a rowdy ‘Toccata’ that begins with a forceful [016] sonority played on four<br />

successive downbows. This is immediately contrasted with a quieter section, a combination of<br />

pizzicati strings and folksy viola. For 26 measures these alternate in a tug-of-war, before giving way<br />

to a nervous B section. In this section the strings present an ostinato on an [0127]; much like the<br />

first movement, each player takes a turn playing his signature theme against the backdrop. As<br />

players increasingly quote (and even trade) their respective themes and abandon the ostinato, the<br />

tension increases, driving us into a short restatement of the original measures.<br />

The third movement is entitled ‘Chorale’ and alternates sections of counterpoint with cadences. The<br />

main theme is presented by the first violin, and is complemented by the other players who enter in<br />

turn. The movement is comprised of increasingly tense sections (in which each of the instruments<br />

presents a take on the main theme) which ‘resolve’ into cadences. After 38 measures, the players<br />

play a single F natural, then fan out chromatically into a chord. This occurs two more times; after<br />

the latter, the viola is left holding that same F natural, which provides a sort of tonal base against the<br />

restating of the original theme by the other instruments. The work ends with the first violin holding<br />

an F-sharp against the B-flat major triad in the other instruments, providing a peaceful, if somewhat<br />

uncertain, close.<br />

The String Quartet No. 2 will be premiered by Sam Arnold, Allison Chetta, Lydia Minnick, and Chris<br />

Erickson.<br />

WIND QUINTET NO. 1 ‘QUODLIBETS’<br />

I’ve always enjoyed small wind ensembles because the great mixture of timbres can create any<br />

number of moods and colors. I chose to follow the pensive string quartet with a playful wind<br />

quintet because it’s always quite enjoyable writing music in a more lighthearted vein. In planning the<br />

quartet, I considered a number of possibilities, but settled on a style used for several centuries: the<br />

quodlibet.<br />

A quodlibet is a work which combines popular tunes, usually in a humorous manner. The earliest<br />

quodlibets known are from the 15th century, when musicians would combine folk tunes. As time<br />

went on, composers began to incorporate popular tunes into their works to show their prowess in<br />

contrapuntal styles. Modern composers such as Ives, Cage, Zimmerman, and Berio also used<br />

musical quotations in major works. For my wind quintet, I decided to quote (mostly) well-known<br />

pieces, some quoted more blatantly than others, and juxtapose them with my own melodies,<br />

blending them so that it is at times difficult to tell who wrote what melody.

The first movement is a march and quotes ‘Do you know the muffin man,’ ‘A-hunting we will go,’ a<br />

march by Sousa, and ‘Bringing In the Sheaves’ (the latter an homage to Ives). The second<br />

movement, a graceful waltz, quotes a popular tune by Strauss. The third movement is a bourée,<br />

a dance, often pastoral, originating the the Auvergne region of France. It is in a quick cut time and<br />

features both a melody from Beethoven’s 6th symphony (the Pastoral) and, appropriately, a folk<br />

song from Auvergne.<br />

The fourth movement, a passacaglia, deserves some explanation. Students of composition have for<br />

centuries studied counterpoint, a discipline which requires the composer to write countermelodies to<br />

a cantus firmus (a pre-written melody against which other lines of music are written in a polyphonic<br />

piece). Perhaps the most popular cantus firmus is one by Johannes Fux, a 17th-century master of<br />

counterpoint. This D minor cantus firmus gradually becomes well-known to students of<br />

counterpoint. Since a passacaglia is a series of variations over a fixed bass, a cantus firmus is<br />

needed. Naturally, the Fux D minor proved a logical choice, but in this passacaglia, nothing is<br />

tonal. For the first time, I was allowed to write dissonant, unresolved counterpoint against the<br />

cantus firmus. So, each instrument plays a theme by another composer: a melody from Britten’s<br />

Peter Grimes, a theme from Brahms’ Second Piano Concerto, and Pachelbel’s Canon in D, itself<br />

arguably a passacaglia. After a ‘train wreck,’ I give in and write some tonal counterpoint to the Fux.<br />

The final movement is a gigue, a dance form which often ended Baroque suites. Like those from<br />

the Baroque, this is in a fast 6/8; unlike Baroque works, this quotes a famous English jig as well as<br />

the theme for a well-known early-1960s television show.<br />

The Wind Quintet No. 1 will be premiered by Lydia Carroll, Meagan O’Malley, Fiona Knoll, Aaron<br />

Gellos, and Brittany Batdorf.<br />

FIVE MOTETS<br />

In the Five Motets for choir I’ve set some of my favorite sacred Latin texts. I’ve arranged their order<br />

so that they provide a sort of commentary on the life of Christ. The first motet, O nata lux, deals<br />

with the incarnation:<br />

O Light born of Light, Jesus, redeemer of the world, with loving-kindness deign to receive<br />

supplicant prayer and praise. Thou who once deigned to be clothed in flesh for the sake of the lost,<br />

grant us to be members of thy blessed body.<br />

The second text, O magnum mysterium, is well-known:<br />

O great mystery, and wonderful sacrament, that animals should see the birth of the Lord lying in a<br />

manger. We have witnessed His birth, and heavenly choirs praising the Lord. Alleluia!<br />

The third motet, Tenebrae factae sunt, deals with the crucifixion:<br />

Darkness covered the earth when Jesus was crucified. And around the ninth hour Jesus cried out<br />

with a loud voice: My God, why hast thou forsaken me? And with his head inclined, he gave up his<br />

spirit. Jesus, crying out again with a loud voice, said: Father, into thy hands I commend my spirit.

Ave verum corpus is similarly concerned:<br />

Hail, true Body, born of the virgin Mary, who has truly suffered, was sacrificed on the cross for<br />

mortals, whose side was pierced, whence flowed water and blood: Be for us a foretaste of heaven<br />

during our final examining. O Jesus sweet, O Jesus pure, O Jesus, son of Mary, have mercy on me.<br />

Amen.<br />

The final motet, Ascendit Deus, a Latin version of Psalm 47:5, completes the set by commenting on<br />

the ascension:<br />

God is ascended amid jubilation, and the Lord to the sound of the trumpet. Alleluia!<br />

In creating the sound-world for these motets, I aimed for a style that’s up-to-date yet eerily<br />

reminiscent of earlier choral styles. Throughout the set may be heard echoes of plainchant, parallel<br />

fourths (Machaut, e.g.), and Renaissance cadences. Each motet dons a specific affect, similar to the<br />

Baroque aesthetic: chant in O nata lux, added-tone chords and incidental dissonances in O Magnum,<br />

wrenching dissonance alternating with simple cadences in Tenebrae, chant again in Ave verum corpus,<br />

and jubilation in Ascendit Deus.<br />

Five Motets will be premiered by a chamber choir directed by John Hudson, with pianist Mark Buller.