Scientific American Mind-June/July 2007

Scientific American Mind-June/July 2007

Scientific American Mind-June/July 2007

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

(perspectives)<br />

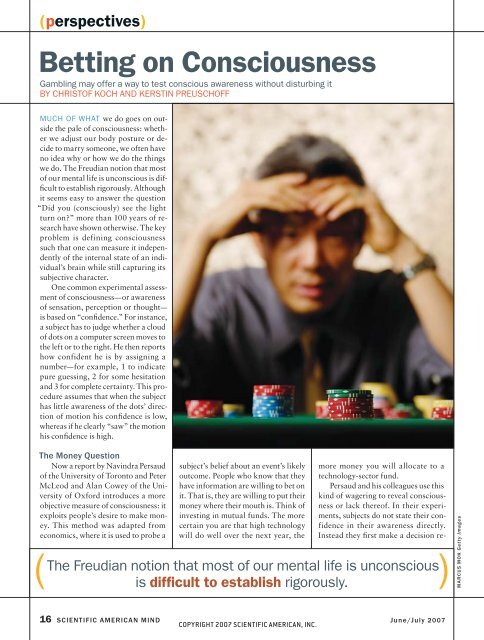

Betting on Consciousness<br />

Gambling may offer a way to test conscious awareness without disturbing it<br />

BY CHRISTOF KOCH AND KERSTIN PREUSCHOFF<br />

MUCH OF WHAT we do goes on outside<br />

the pale of consciousness: whether<br />

we adjust our body posture or decide<br />

to marry someone, we often have<br />

no idea why or how we do the things<br />

we do. The Freudian notion that most<br />

of our mental life is unconscious is diffi<br />

cult to establish rigorously. Although<br />

it seems easy to answer the question<br />

“Did you (consciously) see the light<br />

turn on?” more than 100 years of research<br />

have shown otherwise. The key<br />

problem is defining consciousness<br />

such that one can measure it independently<br />

of the internal state of an individual’s<br />

brain while still capturing its<br />

subjective character.<br />

One common experimental assessment<br />

of consciousness—or awareness<br />

of sensation, perception or thought—<br />

is based on “confi dence.” For instance,<br />

a subject has to judge whether a cloud<br />

of dots on a computer screen moves to<br />

the left or to the right. He then reports<br />

how confident he is by assigning a<br />

number—for example, 1 to indicate<br />

pure guessing, 2 for some hesitation<br />

and 3 for complete certainty. This procedure<br />

assumes that when the subject<br />

has little awareness of the dots’ direction<br />

of motion his confi dence is low,<br />

whereas if he clearly “saw” the motion<br />

his confi dence is high.<br />

The Money Question<br />

Now a report by Navindra Persaud<br />

of the University of Toronto and Peter<br />

McLeod and Alan Cowey of the University<br />

of Oxford introduces a more<br />

objective measure of consciousness: it<br />

exploits people’s desire to make money.<br />

This method was adapted from<br />

economics, where it is used to probe a<br />

subject’s belief about an event’s likely<br />

outcome. People who know that they<br />

have information are willing to bet on<br />

it. That is, they are willing to put their<br />

money where their mouth is. Think of<br />

investing in mutual funds. The more<br />

certain you are that high technology<br />

will do well over the next year, the<br />

more money you will allocate to a<br />

technology-sector fund.<br />

Persaud and his colleagues use this<br />

kind of wagering to reveal consciousness<br />

or lack thereof. In their experiments,<br />

subjects do not state their confidence<br />

in their awareness directly.<br />

Instead they fi rst make a decision re-<br />

( The Freudian notion that most of our mental life is unconscious )<br />

is diffi cult to establish rigorously.<br />

16 SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN MIND <strong>June</strong>/<strong>July</strong> <strong>2007</strong><br />

COPYRIGHT <strong>2007</strong> SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN, INC.<br />

MARCUS MOK Getty Images