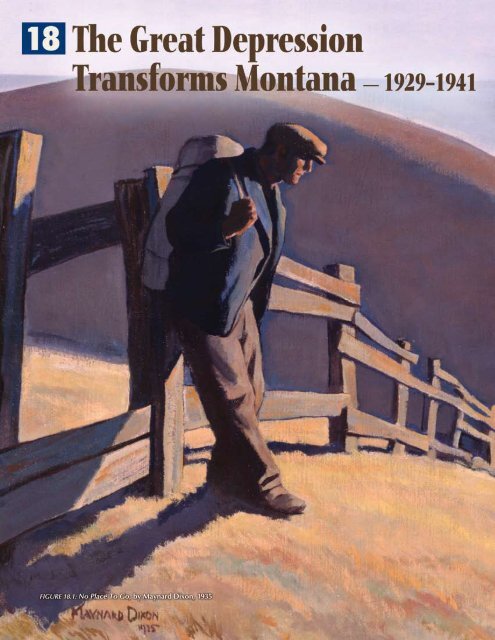

No Place To Go, by Maynard Dixon, 1935 - Montana Historical Society

No Place To Go, by Maynard Dixon, 1935 - Montana Historical Society

No Place To Go, by Maynard Dixon, 1935 - Montana Historical Society

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

FIGURE 18.1: <strong>No</strong> <strong>Place</strong> <strong>To</strong> <strong>Go</strong>, <strong>by</strong> <strong>Maynard</strong> <strong>Dixon</strong>, <strong>1935</strong>

READ TO FIND OUT:<br />

■ Why <strong>Montana</strong>ns were already struggling<br />

when the Great Depression began<br />

■ What <strong>Montana</strong>ns did to survive during<br />

the Great Depression<br />

■ How the government helped put people<br />

back to work<br />

■ How the Great Depression changed <strong>Montana</strong><br />

The Big Picture<br />

The Great Depression brought tremendous hardship<br />

to <strong>Montana</strong> towns and families. Just as hard times<br />

transform a person, the Great Depression changed<br />

<strong>Montana</strong>’s personality.<br />

What was the hardest time you have ever had to live through?<br />

How did surviving that time change you?<br />

In the 1920s and 1930s, <strong>Montana</strong> plunged into a crisis so deep<br />

and so serious that it changed <strong>Montana</strong>’s personality. It affected<br />

everyone who lived here, from the state capital to the Indian<br />

reservations.<br />

The crisis came in two parts. First, a ten-year drought (beginning<br />

in 1917) dried up <strong>Montana</strong>’s farmlands. Homesteaders<br />

lost their crops, their homes, their farms, and their life savings.<br />

Impacts from the drought affected every <strong>Montana</strong> community—<br />

especially in the agricultural east.<br />

Then, in 1929, the U.S. economy crashed. America entered<br />

the worst economic crisis in its history—the Great Depression.<br />

Instead of helping <strong>Montana</strong> out of its economic troubles, the rest<br />

of the country fell into the same desperate condition.<br />

This was a time like no other time in <strong>Montana</strong>. For many<br />

people, the Depression Era was so diffi cult and so painful that it<br />

changed their whole outlook on life. People who had been optimistic<br />

and hopeful became bitter and disappointed. Some became<br />

very suspicious of change. Other people have fond memories<br />

of this time because their families drew closer together. Some<br />

people also benefi ted from some of the changes the Depression<br />

Era brought.<br />

3 5 3

FIGURE 18.2: For <strong>Montana</strong>ns like sheep<br />

rancher Charles McKenzie, the 1920s<br />

and 1930s brought daily toil and few<br />

luxuries.<br />

1915<br />

1917<br />

Drought begins<br />

1919–25<br />

Half of <strong>Montana</strong> farmers<br />

lose their land<br />

1918<br />

World War I ends<br />

354<br />

3 5 4 P A R T 3 : W A V E S O F D E V E L O P M E N T<br />

The Depression changed <strong>Montana</strong> as a state, too. The government<br />

sponsored projects to put unemployed Americans back to work. These<br />

projects brought new technologies and new conveniences like electricity,<br />

telephones, and modern roads to rural areas. Even while the economy<br />

slumped, <strong>Montana</strong> became more modern.<br />

If you have been through a very diffi cult time in your life, chances<br />

are that your ability to survive and heal has become an important part<br />

of who you are. This happens to societies, too. How people survived the<br />

Depression, responded to challenges, and came up with new ideas is an<br />

important part of the <strong>Montana</strong> story.<br />

1920s: Depression Comes Early to <strong>Montana</strong><br />

A host of changes came to <strong>Montana</strong> just before the 1920s. Automobiles<br />

arrived, making travel and transportation much easier—especially for<br />

people who lived in the country. The Progressive Era brought new laws<br />

to improve life and make government work better. <strong>Montana</strong>’s homesteading<br />

boom brought thousands of new residents. They carved up<br />

most of its last remaining open<br />

lands into farms, ranches, and<br />

townships.<br />

America’s involvement in<br />

World War I boosted <strong>Montana</strong>’s<br />

economy. The war created a huge<br />

demand for <strong>Montana</strong>’s copper,<br />

lumber, and wheat. Then the infl<br />

uenza epidemic of 1918 killed<br />

5,000 <strong>Montana</strong>ns in their beds.<br />

Before the events of this chapter<br />

began, <strong>Montana</strong> already was undergoing<br />

many changes.<br />

In 1917 the drought began: years<br />

of dry, hot summers; springs with<br />

no rain. In 1918 World War I ended.<br />

The military canceled its purchases<br />

1920 1925<br />

1924<br />

State taxes increased on<br />

mining companies<br />

1928<br />

<strong>Montana</strong> has 50 paved<br />

miles of highway

of copper, lumber, and wheat. The price of copper<br />

plummeted (fell dramatically). Thousands<br />

of lumbermen, miners, and smelter workers lost<br />

their jobs. Farmers had planted as much wheat<br />

as they could—and no other crop—to support<br />

the war. But when wartime demand disappeared,<br />

farmers could no longer make a living.<br />

Half of <strong>Montana</strong>’s farmers lost their land between 1919 and 1925, and<br />

70,000 people moved away. Businesses failed, banks closed, and many families<br />

lost their life savings. When people could not pay their taxes, county<br />

governments went bankrupt. While much of the rest of the country<br />

enjoyed growth and prosperity in the 1920s, <strong>Montana</strong> struggled.<br />

Drought destroyed many farms on the Indian reservations. Without<br />

crops to sell, many Indian farmers sold off their lands. Tribes already<br />

battled against allotment (the federal program of subdividing Indian<br />

reservations into privately owned parcels), which subdivided some<br />

reservations (land that tribes had reserved for their own use through<br />

treaties) and sold off millions of acres of Indian-owned lands to farmers<br />

and homesteaders (see Chapters 11 and 13).<br />

Hope Dawns—Briefl y<br />

1929<br />

U.S. stock market crashes<br />

1932<br />

Franklin Delano Roosevelt<br />

elected president<br />

1930<br />

Drought returns<br />

“<br />

In the mid-1920s rain began to fall again—in some places. Crops grew,<br />

and some farmers began to prosper again, especially those who had<br />

adopted good conservation techniques and who had planted a variety<br />

of crops.<br />

Another thing helped farmers prosper: bigger farms. The drought<br />

had driven thousands of homesteaders off their land. The farmers who<br />

survived could buy up neighboring farms at very low prices. Gas-driven<br />

tractors and trucks enabled them to work more land. They had learned<br />

that standard 160- or 320-acre homesteads could not produce enough<br />

to support a family—but a 1,000-acre farm could.<br />

A new tax law also brought relief. Until 1924 mining companies like<br />

the Anaconda Copper Mining Company paid the lowest state taxes of<br />

any group in <strong>Montana</strong>—yet earned more money than other industries.<br />

1933<br />

New Deal begins<br />

1934<br />

Congress passes the<br />

Indian Reorganization<br />

Act (IRA)<br />

1933<br />

<strong>Go</strong>ing-to-the-Sun Road in<br />

Glacier National Park opens<br />

Windstorms normally lasted three days.<br />

The wind rose in early morning, died<br />

down toward the third evening, and<br />

rose again before sun-up.<br />

”<br />

—CHARLES VINDEX, A FARMER NEAR PLENTYWOOD<br />

1936<br />

Beartooth<br />

Highway<br />

opens<br />

1934<br />

International Mine, Mill and<br />

Smelterworkers strike revitalizes<br />

<strong>Montana</strong> union movement<br />

1939<br />

World War II<br />

begins in Europe<br />

1937<br />

Drought ends<br />

1941<br />

United States enters<br />

World War II<br />

1930 <strong>1935</strong> 1940<br />

1941<br />

<strong>Montana</strong> has more than<br />

7,000 miles of paved roads<br />

(thanks to the New Deal)<br />

355<br />

1 3 — H O M E S T E A D I N G T H I S D R Y L A N D 3 5 5

FIGURE 18.3: Many <strong>Montana</strong>ns, like this thin,<br />

tired woman of Flathead Valley, were used<br />

to working hard to build a better life for their<br />

families. But when they lost what little they<br />

had during the Depression, they wondered<br />

if it was all worth it.<br />

FIGURE 18.4: Millions of Mormon crickets<br />

hopped across <strong>Montana</strong>’s farmlands in the<br />

1930s. Farmers dug trenches and built metal<br />

fences around their crops to keep them out,<br />

but the Mormon crickets just piled up and<br />

walked over one another’s backs. Here a Big<br />

Horn County farmer cleans out a cricket trap.<br />

3 5 6 P A R T 3 : W A V E S O F D E V E L O P M E N T<br />

In 1924 <strong>Go</strong>vernor Joseph <strong>Dixon</strong>, a Progressive, supported an initiative<br />

(a law passed <strong>by</strong> the people rather than <strong>by</strong> the legislature) increasing<br />

state taxes on mining companies. The new tax law made mine owners<br />

pay a larger share. The Company made sure that <strong>Dixon</strong> lost his bid for<br />

reelection for what he had done. But the initiative succeeded. Farmers<br />

no longer had to pay most of the costs of state government. Life started<br />

to look more hopeful for <strong>Montana</strong>’s farmers.<br />

The World Comes Crashing Down<br />

In 1929 the entire U.S. economy crashed. A deep and lasting economic<br />

depression hit the United States, Canada, and most of the developed<br />

countries of the world. It was the worst economic crisis in U.S. history.<br />

The stock market crashed. The average income of American workers was<br />

cut in half. Thousands of businesses and banks failed, and across the<br />

country one out of every four workers lost his or her job.<br />

Historians still argue about what really caused the Great Depression<br />

of 1929–41. Most of them agree it was a combination of forces. But the<br />

results were devastating. Across the United States, people became almost<br />

as poor as many <strong>Montana</strong>ns had been for a decade.<br />

The Great Depression pitched <strong>Montana</strong>’s economy into a downward<br />

spiral. Crop prices dropped sharply again. Beef prices collapsed.<br />

The price of copper fell from 18 cents per pound to 5 cents per pound.<br />

The Anaconda Copper Mining Company cut its production levels <strong>by</strong><br />

90 percent. Industrial plants in Butte, Anaconda, East<br />

Helena, and Great Falls closed. Mines and smelters laid<br />

off thousands of workers. Every industry suffered.<br />

Drought Returns—Worse than Ever<br />

Then, in 1930, the drought returned. This time it covered<br />

the entire Plains region from Canada to Mexico,<br />

from the Rocky Mountains to the Mississippi River.<br />

The Plains became so dry that great swaths of topsoil<br />

simply blew away in hot, dry windstorms. Swarms of<br />

grasshoppers fl ew so thick they blotted out the sun.<br />

Mormon crickets marched across the dry soil, devouring<br />

everything in their path.<br />

A weather observer said that 1931 was the driest in<br />

30 years—only 5.67 inches of rain, less than half the<br />

normal annual rainfall. A farmer in Daniels County<br />

wrote in his diary, “The world is a dreary spot for<br />

<strong>Montana</strong> grain growers.”<br />

That year <strong>Go</strong>vernor John Erickson visited Scobey, a<br />

town that promoted itself as the world’s largest wheatshipping<br />

town. What he saw made him bury his head

in his hands. Of the 5,000 people living in Daniels<br />

County, 3,500 of them were broke.<br />

What Would You Do?<br />

What would you do if you could not work,<br />

could not grow food, and had no money? Many<br />

<strong>Montana</strong>ns left for the West Coast, where things<br />

were not as bad. Many others found part-time<br />

work or odd jobs.<br />

Charles Vindex, a farmer outside Plentywood,<br />

helped a neighbor cut and store ice, sawing until his<br />

muscles trembled. “I would have said this was the<br />

hardest work a man could do for $1.25,” he wrote<br />

later. “A year later I did the same job for 75¢ a day.”<br />

For the fi rst few years at least, the farmers could<br />

feed their families on what they grew. City folk had<br />

it tougher. With no jobs, no money, and no hope,<br />

they appealed to the Red Cross and other agencies<br />

for aid.<br />

People scrimped (used less) and re-used<br />

everything they could. Neighbors shared labor,<br />

wagons, cars, and water. They patched their clothes,<br />

then patched the patches. When their clothes wore out altogether, they<br />

cut them into strips and wove rugs out of them. All across the state,<br />

people hunted deer and elk until they nearly wiped them out. When one<br />

group studied people in Butte in 1934, they discovered that fi ve out of<br />

every six kids were malnourished (seriously underfed).<br />

Local Relief Efforts<br />

Were <strong>No</strong>t Enough<br />

<strong>To</strong>wns and counties started their own programs<br />

for work relief (relieving poverty<br />

<strong>by</strong> giving people jobs). <strong>To</strong>wns hired men<br />

to build playgrounds and parks. Counties<br />

hired teams to build roads. But with so<br />

many people too poor to pay their taxes,<br />

towns and counties quickly ran out of<br />

money to hire people.<br />

Charities set up food banks and distributed<br />

clothing to people in desperate<br />

need. In 1931 the Red Cross shipped to<br />

<strong>Montana</strong> and <strong>No</strong>rth Dakota 200 freightcar<br />

loads of food and clothing donated<br />

from people in other states. But soon the<br />

“<br />

A Letter from the<br />

Depths of Despair<br />

“I am an old man, 70 years old. I and my old<br />

wife at the present time have one baking of<br />

flour left and one pound of coffee. We have<br />

no credit and no work . . . We have lived here<br />

20 years and I have paid $3,500 in taxes<br />

since I have been in <strong>Montana</strong> and this is the<br />

end. What can you or anyone do about it?”<br />

—J. E. FINCH, FARMER NEAR SUMATRA, IN A LETTER<br />

TO GOVERNOR JOHN ERICKSON, JULY 16, 1931<br />

Our family hadn’t had a crop in four<br />

years. When you went to lunch,<br />

the grasshoppers would gnaw at<br />

the salt from your hands on your<br />

pitchfork. Anyone who could get<br />

out did.<br />

”<br />

—SAM RICHARDSON, WHO FARMED IN DANIELS COUNTY<br />

FIGURE 18.5: Many Americans were<br />

horrifi ed at the idea of being “down<br />

and out”—so bad off that they could<br />

not take care of themselves. So when<br />

people helped one another, they also<br />

offered encouragement. This woman<br />

serves dinner to two unemployed<br />

men at the Salvation Army in Butte.<br />

1 8 — T H E G R E A T D E P R E S S I O N T R A N S F O R M S M O N T A N A 3 5 7

“<br />

“<br />

Many of us have put in the best years of<br />

our life out here; we know what hardship,<br />

privation and hard work means.<br />

We realize that we must start over<br />

somewhere else, as we have lost faith<br />

and confi dence in this part of the country.<br />

It isn’t easy for us to give up our<br />

homes and admit defeat but we must<br />

admit that we are done.”<br />

—WARNER JUST, GARFIELD COUNTY FARMER, WRITING<br />

TO SENATOR JAMES E. MURRAY, AUGUST 10, 1936<br />

The thirties I don’t want to remember at<br />

all. That was bad all the way through . . .<br />

<strong>No</strong>body had any money . . . You could buy<br />

a set of overalls for 25 cents but nobody had<br />

25 cents. ”—WALLACE LOCKIE, MONTANA FARMER<br />

FIGURE 18.6: Some people packed up and<br />

moved to the West Coast, where there were<br />

more opportunities. More than once, road<br />

crews working on MacDonald Pass (east of<br />

Helena) had to help heavily packed automobiles<br />

get over the pass. They sometimes<br />

gave the desperate families an extra dollar<br />

or two to help out.<br />

3 5 8 P A R T 3 : W A V E S O F D E V E L O P M E N T<br />

churches and the charities were overwhelmed.<br />

There were just too many families in need. For<br />

<strong>Montana</strong>ns who had carved farms out of the<br />

grasslands <strong>by</strong> hard work and stout-heartedness,<br />

asking for help was humiliating.<br />

<strong>Montana</strong> hit bottom between 1930 and<br />

1932. In 1930 one out of every four <strong>Montana</strong><br />

households received some kind of aid. In<br />

January 1931 <strong>Go</strong>vernor Erickson told the<br />

legislature (the branch of government that<br />

passes laws) that he thought “the great<br />

heart of the people of <strong>Montana</strong> will see<br />

to it that destitution [extreme pov-<br />

erty] and suffering are relieved.” But he<br />

also told the legislature not to spend<br />

any more money. The state had no<br />

more money to provide relief, anyway.<br />

<strong>Montana</strong>, along with many other states,<br />

began pressuring the federal government<br />

to help.<br />

The 1932 Election: How Should the <strong>Go</strong>vernment Help?<br />

If you were president, what would you do? Herbert Hoover, a Republican,<br />

was president of the United States in 1931. He did not think the government<br />

should directly help poor people. He feared that giving aid directly<br />

to poor people would make them dependent<br />

on the government. He thought that<br />

relief to individual families should come<br />

from private sources—churches, charities,<br />

and the Red Cross.<br />

Hoover thought that government<br />

should aid businesses. If businesses were<br />

healthy, people would get their jobs back<br />

and the economy would recover. He<br />

thought that people needed jobs more<br />

than food. “<strong>No</strong>body is starving,” he said.<br />

But people were starving. Even if they<br />

were not dying in the streets, long-term<br />

poverty had weakened the health of<br />

even hardy people. Some of the hardest<br />

hit were disabled people who had been<br />

injured while working and could not get<br />

work at all.<br />

The election of 1932 pitted two opposing<br />

political ideas against each other.

LINCOLN<br />

Hoover’s opponent was Franklin D. Roosevelt,<br />

a Democrat. Roosevelt thought that the government<br />

should use its resources to help the<br />

millions of people who were suffering. He<br />

proposed that the government strike a “new<br />

deal” with the American people. Under this<br />

“new deal,” the government would feed huge<br />

amounts of money into each troubled state<br />

to build roads, bridges, dams, sewer systems,<br />

and other improvements. The government<br />

would also provide loans to farmers to get<br />

through the tough years and back on their feet.<br />

The voters overwhelmingly elected Franklin D. Roosevelt. As<br />

soon as he took offi ce, in 1933, his New Deal programs began.<br />

Roosevelt knew that two of his most powerful supporters were<br />

<strong>Montana</strong>’s two Democratic senators, Thomas J. Walsh (a senator from<br />

1913 to 1933) and Burton K. Wheeler (a senator from 1923 to 1947). He<br />

later repaid Walsh and Wheeler for their political backing <strong>by</strong> sending<br />

important projects to <strong>Montana</strong>.<br />

SANDERS<br />

MINERAL<br />

FLATHEAD<br />

LAKE<br />

MISSOULA<br />

RAVALLI<br />

GLACIER<br />

GRANITE POWELL<br />

SILVER<br />

BOW<br />

DEER LODGE<br />

BEAVERHEAD<br />

PONDERA<br />

TETON<br />

LEWIS<br />

&<br />

CLARK<br />

JEFFERSON<br />

MADISON<br />

TOOLE<br />

CASCADE<br />

BROAD-<br />

WATER<br />

LIBERTY<br />

GALLATIN<br />

CHOUTEAU<br />

MEAGHER<br />

PARK<br />

“<br />

HILL<br />

JUDITH<br />

BASIN<br />

“<br />

We became shy of other people<br />

during those patched and shab<strong>by</strong><br />

years. ”—CHARLES VINDEX<br />

The world owes no man a living, but it<br />

certainly owes all of its people a chance<br />

to make a living.<br />

”<br />

—JOHN F. HAUGE, A GROCER IN PARADISE, WRITING TO<br />

GOVERNOR JOHN E. ERICKSON, NOVEMBER 1931<br />

BLAINE<br />

WHEATLAND<br />

MUSSELSHELL<br />

GOLDEN<br />

VALLEY<br />

SWEET<br />

GRASS<br />

STILLWATER<br />

CARBON<br />

0-10<br />

11-20<br />

PHILLIPS<br />

FERGUS GARFIELD<br />

PETROLEUM<br />

YELLOWSTONE<br />

21-30<br />

31-40<br />

TREASURE<br />

BIG HORN<br />

VALLEY<br />

ROSEBUD<br />

MCCONE<br />

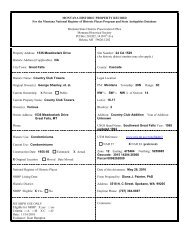

Percentage of <strong>Montana</strong>ns on Relief <strong>by</strong> County, February <strong>1935</strong><br />

FIGURE 18.7: In February <strong>1935</strong> all but<br />

ten <strong>Montana</strong> counties had more than<br />

10 percent of their population on relief.<br />

DANIELS SHERIDAN<br />

ROOSEVELT<br />

CUSTER<br />

DAWSON<br />

PRAIRIE<br />

POWDER<br />

RIVER<br />

RICHLAND<br />

WIBAUX<br />

FALLON<br />

CARTER<br />

1 8 — T H E G R E A T D E P R E S S I O N T R A N S F O R M S M O N T A N A 3 5 9

FIGURE 18.8: President Franklin D.<br />

Roosevelt, shown here at Fort Peck,<br />

visited <strong>Montana</strong> three times during<br />

the 1930s. Tribal leaders at the Fort<br />

Peck Indian Reservation made him<br />

an honorary chief in 1934.<br />

3 6 0 P A R T 3 : W A V E S O F D E V E L O P M E N T<br />

Roosevelt and the New Deal<br />

Roosevelt’s New Deal lasted from 1933 to 1939. It had three goals: to<br />

bring relief to hungry, unemployed people; to help the economy to recover;<br />

and to bring reforms that would make sure an economic crisis<br />

like this never happened again.<br />

First, Roosevelt sent relief funds to each state to help the people who<br />

were in the most desperate situations. He closed all the banks temporarily<br />

so they could reorganize and open up again on stronger footing. The<br />

government also created a federal insurance program for banks. <strong>To</strong>day,<br />

if your bank fails, the government insures your family’s deposits so you<br />

would not lose your life savings.<br />

The second phase was a series of work programs. These programs<br />

put unemployed people back to work. They brought practical, muchneeded<br />

improvements to cities and counties across the country. And <strong>by</strong><br />

doing these things, they restored hope and pride to people whose spirits<br />

had been crushed <strong>by</strong> despair.<br />

The New Deal included an alphabet of laws and programs designed<br />

to improve the economy:<br />

• AAA (1933)—The Agricultural Adjustment Acts were several laws<br />

to help farmers. They allowed the government to raise prices of farm<br />

goods and to pay farmers to reduce their crop production so that<br />

there would not be so much extra on the market. The AAA brought

“<br />

between $5 million and $10 million to <strong>Montana</strong><br />

farmers. They came to rely on this program to<br />

survive.<br />

• FCA (1933)—The Farm Credit Administration<br />

gave farmers easy loans so they could pay<br />

taxes and buy grain. This program helped prevent<br />

farmers from losing their land, as so many had in the 1920s.<br />

• REA (<strong>1935</strong>)—The Rural Electrifi cation Administration formed<br />

non-profi t corporations to provide electricity to rural farms and<br />

ranches. Low-cost electricity greatly improved life in <strong>Montana</strong>’s<br />

rural communities. It also created competition for <strong>Montana</strong> Power<br />

Company—which was not pleased.<br />

• CCC (1933)—The Civilian Conservation Corps was one of the<br />

most popular of the New Deal programs. The CCC hired young men<br />

17 to 25 years old to work in national parks, national forests, state<br />

forests, and campgrounds. They fought fi res, planted trees, and prevented<br />

stream bank erosion (wearing away). They also built trails,<br />

fi re lookout towers, and campgrounds. Young men earned $30 per<br />

month (equal to about $467 today), kept $5, and sent $25 home<br />

to their families. By the time the program ended, in 1942, it had<br />

employed nearly 3 million young men around the country.<br />

• NIRA (1933) and Wagner Act (<strong>1935</strong>)—The National Industrial<br />

Recovery Act and the Wagner Act guaranteed workers the right to<br />

organize unions. Anaconda Copper Mining Company workers took<br />

advantage of these laws, striking for higher wages in 1934.<br />

When you listened to Franklin D., you<br />

were listening to hope.<br />

”<br />

—JOHN C. HARRISON OF THE JUDITH BASIN, WHO WAS<br />

16 WHEN THE GREAT DEPRESSION BEGAN<br />

FIGURE 18.9: The WPA—Works<br />

Progress Administration—created<br />

projects to put people to work and<br />

improve their communities. The WPA<br />

sponsored bookmobiles like this one<br />

in Fairfi eld. Trucks from town libraries<br />

drove to neighborhoods and rural areas<br />

carrying library books, which residents<br />

could check out and return the next<br />

time the bookmobile came through.<br />

1 8 — T H E G R E A T D E P R E S S I O N T R A N S F O R M S M O N T A N A 3 6 1

We Learned to Drive<br />

on the Fort Peck Project<br />

“Erick Olson, who went to work on the Fort<br />

Peck Dam in the mid-1930s, recalled that he<br />

‘never knew what a tractor was till I got to<br />

Fort Peck.’ A superintendent came up to his<br />

crew one day and asked, ‘Is there any man<br />

here that can drive a pick-up?’ And there<br />

never was a hand that had lifted and he went<br />

on to the next crew and do you know there<br />

was not a man that could drive a pick-up.’<br />

Olson learned to drive on the Fort Peck job.”<br />

—MARY MURPHY, HOPE IN HARD TIMES (2003)<br />

FIGURE 18.10: Indian Civilian<br />

Conservation Corps crews, like<br />

this Blackfeet logging and forestry<br />

crew, provided needed jobs on<br />

the reservation.<br />

3 6 2 P A R T 3 : W A V E S O F D E V E L O P M E N T<br />

• PWA (1933)—The Public Works Administration<br />

built large projects designed to improve the infrastructure<br />

(basic facilities, such as roads,<br />

bridges, water, sewer, and communications) of<br />

the nation. In <strong>Montana</strong>, the PWA built sewagedisposal<br />

plants, hospitals, and its largest project,<br />

the Fort Peck Dam.<br />

• WPA (<strong>1935</strong>)—The Works Progress Administration—like<br />

the PWA—was designed to put<br />

people to work. The WPA hired 20,000 people<br />

to build roads and bridges, schools, airports,<br />

water systems, and sewers. It built 10,000 new<br />

privies (outhouses) in rural areas. This program<br />

also sponsored artistic and cultural projects for<br />

writers, musicians, and photographers.<br />

Of all these programs, the CCC, the PWA, and<br />

the WPA put the most <strong>Montana</strong>ns to work. CCC crew members built<br />

many of our parks and campgrounds. Women in WPA sewing rooms<br />

sewed more than 800,000 garments, curtains, bedspreads, and rugs for<br />

the relief program. The WPA paid dentists, doctors, and nurses to provide<br />

health care. Every day we drive over roads and bridges built <strong>by</strong> the<br />

WPA, though no one still uses the privies they built.<br />

Other WPA workers created remarkable, lasting works that are<br />

important records of twentieth-century America. Writers and photographers<br />

contributed unforgettable artworks documenting many cultures<br />

and aspects of life. Culture committees began recording oral histories<br />

and stories of Indian tribes.

New Deal Projects Brought Jobs to the Reservations<br />

On Indian reservations, many people were already so poor that the<br />

Depression made little difference. When New Deal programs brought<br />

jobs to the reservations, many families began to rise out of poverty.<br />

An American Indian Division of the CCC hired young men on the<br />

reservations to build water reservoirs, dig wells, fi ght fi res, and help with<br />

other federal projects. CCC jobs gave workers housing, food, and a small<br />

salary, which they would not have had otherwise.<br />

Crow tribal historian Joe Medicine Crow later said that even though<br />

the pay was low, the CCC jobs were important to Crow men. “Up to that<br />

time there were no jobs for Indians here,” he said. “The Crow found<br />

work, employment from the government—maybe only $30 a month.<br />

Dollar a day. But they are making money. Something new. They learned<br />

to become professionals in carpentry and heavy equipment operating.”<br />

Fort Peck Dam: Enduring Symbol of the New Deal<br />

President Roosevelt owed <strong>Montana</strong> senators Burton K. Wheeler and<br />

Thomas J. Walsh a favor for helping him get elected. That favor became<br />

the biggest PWA project in the country: the Fort Peck Dam.<br />

Construction started in 1934 on the Missouri River just above the<br />

mouth of the Milk River. When it was fi nished, in 1940, it was the largest<br />

earth-fi lled dam in the world. It created the fi fth-largest human-made<br />

lake in the country—16 miles wide and 134 miles long. The dam stands<br />

258 feet at its highest, and stretches 2 miles wide.<br />

The Fort Peck Dam brought<br />

11,000 workers from all over<br />

<strong>Montana</strong> and elsewhere into Valley<br />

and McCone Counties at the southwest<br />

edge of the Fort Peck Indian<br />

Reservation. Little towns like<br />

Wheeler, New Deal, and Delano<br />

Heights (Delano was Roosevelt’s<br />

middle name) sprang up to house,<br />

feed, and entertain laborers. Many<br />

of those people, newly trained in<br />

skilled jobs, stayed in <strong>Montana</strong> to<br />

raise their families after the dam<br />

was complete.<br />

The dam’s turbines (motors<br />

powered <strong>by</strong> water) created 185,250<br />

kilowatts of electricity that provided<br />

power to the region. The dam also<br />

gave the Army Corps of Engineers<br />

the ability to manage the Missouri<br />

FIGURE 18.11: The Fort Peck Dam was an<br />

immense example of American muscle and<br />

engineering know-how. It immediately became<br />

a symbol of America’s recovery from<br />

the Great Depression.<br />

FIGURE 18.12: One of the goals of the Fort<br />

Peck Dam project was to put unemployed<br />

Americans back to work. But not everyone<br />

pictured in this <strong>No</strong>vember 25, 1936, photo<br />

is actually working. The offi cials in hats on<br />

the upper left have come to observe, and<br />

some of the workers on the upper right<br />

just want to be in the picture.<br />

1 8 — T H E G R E A T D E P R E S S I O N T R A N S F O R M S M O N T A N A 3 6 3

FIGURE 18.13: During the 1930s government<br />

photographers traveled across the<br />

country documenting the effects of the<br />

Depression and the success of New Deal<br />

programs. This picture was taken in<br />

Teton County.<br />

3 6 4 P A R T 3 : W A V E S O F D E V E L O P M E N T<br />

River’s fl ow <strong>by</strong> holding or releasing water as needed to prevent fl ooding<br />

downstream. More than anything else, the dam became a powerful symbol<br />

of hope and strength to a nation that had almost lost faith in itself.<br />

Unions Regain Strength<br />

The 1933 National Industrial Recovery Act revived unions in western<br />

<strong>Montana</strong>. Unions had lost strength during World War I, when patriotism<br />

and industrial production were more important than workers’ rights. But<br />

during the Depression, more people supported the labor unions.<br />

In May 1934 the International Mine, Mill and Smelterworkers Union<br />

went on strike (an organized protest in which workers refuse to work)<br />

against the Anaconda Copper Mining Company. They demanded<br />

higher pay, a 40-hour workweek, and safety improvements. They also<br />

demanded that Anaconda hire only union members for its laborers.<br />

Eleven other unions joined the walkout. Even state leaders agreed with<br />

the strike.<br />

In previous strikes, the Company had been<br />

able to call on the government to force laborers<br />

back to work. But this time the public strongly<br />

supported the unionists. Anaconda agreed<br />

to many of the union’s demands. The strikers’<br />

victory began a new day for <strong>Montana</strong>’s<br />

unions, whose political and economic power<br />

grew in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s.<br />

The “New Deal”<br />

for American Indians<br />

In the 1920s many Americans complained<br />

to the government that the Indian reservations<br />

had been appallingly mismanaged. So<br />

many people spoke out that the government<br />

decided to study the matter. In 1926 the government<br />

sent out a team of researchers, led<br />

<strong>by</strong> Lewis Meriam, to see what life was like<br />

on Indian reservations. For two years they<br />

visited reservation homes, schools, hospitals,<br />

and agencies across the West.<br />

Meriam’s 800-page report strongly criticized<br />

the federal government for its treatment<br />

of American Indians. It told of Indian people<br />

struggling against the worst poverty in the<br />

nation, living on unfarmable land with no<br />

jobs and no opportunities. American Indians,<br />

the report said, made less than one-tenth the

average income of most Americans. They were malnourished and sick<br />

with curable diseases. Their children were still being sent off to faraway<br />

boarding schools. Meanwhile, the report said, the government misused<br />

tribal funds and ignored the needs of Indian people.<br />

The Meriam Report called for immediate, widespread changes in<br />

federal Indian policy.<br />

The Indian Reorganization Act<br />

Roosevelt appointed John Collier as commissioner of Indian affairs.<br />

Collier was an outspoken advocate (supporter) of American Indian<br />

rights. He called the earlier federal policy to erase tribal cultures and to<br />

assimilate (to absorb into the majority culture) Indian people “a crime<br />

against the earth.”<br />

When he took offi ce, Collier learned that since the Allotment Act of<br />

1887 (also known as the Dawes Act), Indian lands had shrunk from 138<br />

million acres to 47 million acres. Tribal funds had shriveled from $500<br />

million to $12 million. Most of these funds had gone to government<br />

expenses and corruption—not to help the tribes.<br />

Collier pushed Congress to pass new laws that would give tribes<br />

more say over their own future. He called for Congress to “stop wronging<br />

the Indians and to rewrite the cruel and stupid laws that rob them<br />

and crush their family lives.”<br />

In 1934 Congress passed the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA).<br />

<strong>Montana</strong> senator Burton K. Wheeler cosponsored the act, so it was also<br />

called the Wheeler-Howard Act.<br />

The IRA radically changed U.S. policy toward American Indians.<br />

Instead of trying to destroy tribal<br />

cultures, federal policy now gave tribes<br />

some limited powers of self-government<br />

and encouraged them to strengthen their<br />

cultures.<br />

The IRA was one of the most important<br />

laws affecting Indian tribes since<br />

the Dawes Act. It put an end to the<br />

allotment system, which had removed<br />

so much land from Indian ownership<br />

(see Chapter 11). It also returned some<br />

land back to tribes.<br />

The IRA also established several<br />

important rights for American Indians:<br />

• The right to establish tribal governments<br />

with their own constitutions<br />

(documents that set rules for government)—still<br />

subject to the approval of<br />

the federal government, however.<br />

FIGURE 18.14: Even after <strong>Montana</strong>ns<br />

went back to work, they remembered<br />

the lessons of the boom-and-bust<br />

cycle. Some families moved into nicer<br />

houses, but others—like the Butte<br />

owners of this new automobile—spent<br />

money only on things they could take<br />

with them if the bust came again.<br />

1 8 — T H E G R E A T D E P R E S S I O N T R A N S F O R M S M O N T A N A 3 6 5

FIGURE 18.15: After the Indian<br />

Reorganization Act was passed,<br />

tribes across the West could once<br />

again hold Sun Dances and other<br />

religious ceremonies without being<br />

punished <strong>by</strong> the government. Here<br />

<strong>No</strong>rthern Cheyenne families bring<br />

food offerings to a medicine lodge<br />

during a Sun Dance in the 1930s.<br />

3 6 6 P A R T 3 : W A V E S O F D E V E L O P M E N T<br />

• The right to form business corporations and to get federal loans so<br />

they could participate in the economy.<br />

• The right to practice their own religion (the government prohibited<br />

Indian religious ceremonies in the early reservation years).<br />

• An immediate end to federal funding for off-reservation boarding<br />

schools.<br />

• More infl uence within the Bureau of Indian Affairs so American Indians<br />

could have a bigger say in their own future.<br />

Some tribes objected to the IRA because it required tribes to set up<br />

their governments like the U.S. government, with representatives and<br />

constitutions. It did not allow the tribes to return to their own traditional<br />

forms of government. The Bureau of Indian Affairs wrote a standard constitution<br />

for all the tribes to adopt. Even though the IRA gave tribes more<br />

powers, the government still supervised everything they did.<br />

In the end 181 tribes accepted the IRA, created tribal governments, and<br />

adopted the constitution given them. Most of these tribes have revised their<br />

constitutions over the years to better suit their people and traditions.<br />

About one-third of the Indian tribes in the country rejected the IRA.<br />

The Crow tribe was one. The Crow people wrote and adopted their own<br />

constitution in 1948 that more closely refl ected tribal traditions.<br />

In the fi rst 15 years after the IRA passed, more than 70 tribes used<br />

federal loans to set up businesses—and paid off the loans. The number<br />

of Indian-owned cattle ranches doubled. The death rates on reservations<br />

dropped in half. And to the joy and relief of Indian parents nationwide, 16

oarding schools closed (or turned into day schools) and 84 day schools<br />

opened in reservation towns.<br />

The IRA did not improve everything. It did not restore to the tribes the<br />

millions of acres of land lost in allotments. And it did not allow tribes to<br />

return to their traditional methods of government. While tribes struggled<br />

to rebuild their cultures after 50 years of forced assimilation (when<br />

one culture is absorbed into the majority culture), they still had to follow<br />

government rules. Many Indian people found this very frustrating.<br />

A New <strong>Montana</strong> Emerges<br />

In 1937 the drought broke. Rains fell,<br />

crops grew, and <strong>Montana</strong>’s economy<br />

slowly began to come alive again.<br />

Businesses expanded and hired more<br />

people in permanent jobs. Stronger<br />

labor unions brought improved<br />

working conditions for laborers and<br />

craft workers.<br />

A new <strong>Montana</strong> emerged from<br />

the Great Depression. Telephones and<br />

electricity came to many rural areas,<br />

making life easier and improving communication.<br />

Nearly half the farms had<br />

gas-powered trucks and tractors. Roads<br />

and automobiles brought people together<br />

and brought crops to market.<br />

New Deal projects had changed<br />

farmers into skilled industrial workers.<br />

Many young men saw no future<br />

in farming or had lost their land.<br />

They learned new skills building the<br />

Fort Peck Dam or engineering bridges<br />

and roads, and never went back to<br />

the farm.<br />

Thousands of acres of farm and<br />

ranch land had changed hands. The<br />

drought had wiped out all but the<br />

most successful farms. The people who<br />

remained bought up abandoned farmland<br />

for pennies—sometimes 45 cents<br />

an acre. By 1940 the average farm had<br />

increased from 360 acres to over 1,000<br />

acres. Larger farms and ranches stood<br />

a better chance of surviving <strong>Montana</strong>’s<br />

weather cycles.<br />

FIGURE 18.16: State government expanded<br />

to provide more services to the<br />

people—including building and maintaining<br />

state parks. This artful poster<br />

from the 1930s advertised <strong>Montana</strong>’s<br />

state parks to tourists and campers.<br />

1 8 — T H E G R E A T D E P R E S S I O N T R A N S F O R M S M O N T A N A 3 6 7

FIGURE 18.17: The New Deal sent<br />

many <strong>Montana</strong>ns back to work. But<br />

it was World War II that really revved<br />

up <strong>Montana</strong>’s economy, especially<br />

<strong>by</strong> boosting industries that provided<br />

materials used in the war, like<br />

Anaconda’s smelter.<br />

3 6 8 P A R T 3 : W A V E S O F D E V E L O P M E N T<br />

The Depression and the New Deal changed life for the Anaconda<br />

Copper Mining Company. A stronger state government—and stronger<br />

labor unions—limited the Company’s power over <strong>Montana</strong>. The Fort<br />

Peck Dam and federal electrifi cation programs directly competed with<br />

Anaconda’s sister company, the <strong>Montana</strong> Power Company. The government<br />

regulated electricity prices and railroad rates. And, in 1933, the<br />

Company’s forceful leader, John D. Ryan, died.<br />

The Company remained extremely powerful in <strong>Montana</strong>. It still<br />

owned many of the state’s newspapers and still employed more workers<br />

than any other single business in <strong>Montana</strong>. It remained one of the<br />

strongest political forces, too. But after the New Deal, the Company had<br />

to learn to work with other organizations.<br />

A <strong>Go</strong>vernment Presence Everywhere<br />

The Great Depression and the New Deal changed <strong>Montana</strong>’s personality.<br />

The state now depended on the federal government for its economic<br />

stability. New Deal projects had brought<br />

$381.5 million in aid, plus another $142<br />

million in loans, into <strong>Montana</strong>. Because<br />

of the state’s large land base and small<br />

population, it received the secondlargest<br />

aid package in the nation per<br />

capita (person). It totaled $974 in aid and<br />

loans (about $14,300 today) for every<br />

man, woman, and child in <strong>Montana</strong>. <strong>To</strong><br />

this day, <strong>Montana</strong>ns cherish their independence<br />

yet depend on government<br />

programs to make life better.<br />

Farmers came to rely on federal farm<br />

subsidies (fi nancial help from the<br />

government) to survive in an everchanging<br />

market. Counties and state<br />

government relied on federal roadbuilding<br />

programs to provide money<br />

and jobs. And many people came to depend<br />

on other New Deal programs like<br />

Social Security, which provided old-age<br />

pensions (retirement pay) for workers,<br />

the blind, and people with physical disabilities.<br />

This program helped thousands<br />

of <strong>Montana</strong>ns survive if they could<br />

not work.<br />

The state and federal governments<br />

also began managing and preserving<br />

wildlife. Americans had become alarmed

at the loss of wildlife during the Depression. State fi sh and wildlife agencies<br />

worked to restore wildlife populations.<br />

State government expanded dramatically, forming new agencies and<br />

offi ces to handle all the money and programs. State offi ces became more<br />

professional and bureaucratic (concerned with offi cial procedure) to<br />

minimize opportunities for corruption.<br />

By 1940 the Anaconda Copper Mining Company and the railroads<br />

no longer dominated <strong>Montana</strong>. Federal and state government became<br />

an equally important presence.<br />

The New Deal Changed <strong>Montana</strong> Politics<br />

The struggles and changes in this period brought big changes to <strong>Montana</strong>’s<br />

politics. Remember the election of 1932, in which Franklin Roosevelt<br />

challenged Herbert Hoover? These<br />

two candidates presented two very<br />

different views of the responsibilities<br />

of government. Hoover was conservative,<br />

while Roosevelt was liberal.<br />

These terms have many meanings<br />

and they have changed over time.<br />

But generally these terms describe<br />

two opposite forces in our country’s<br />

political life.<br />

Conservatives favor big business,<br />

because business drives the economy,<br />

and small government, because taxes<br />

and government regulations restrict<br />

business activities. People who are<br />

wealthy, own businesses, or have<br />

ties to the military or to evangelical<br />

churches tend to be conservative.<br />

Liberals favor strong government,<br />

because the government represents the<br />

voice of the people against powerful<br />

corporations. They favor more<br />

restrictions on corporate activities that<br />

might harm people, society, or the environment.<br />

Traditionally, scholars and<br />

intellectuals and people who earn<br />

lower or middle incomes, are members<br />

of labor unions, or belong to a nonwhite<br />

ethnic group tend to be liberals.<br />

The Depression Era changed how<br />

<strong>Montana</strong>ns voted. They often elected<br />

conservative leaders at home and sent<br />

FIGURE 18.18: When the Depression<br />

ended, <strong>Montana</strong> was a mix of old<br />

and new. This Fairfi eld sidewalk,<br />

photographed in 1939, still had<br />

an old-fashioned hand pump where<br />

townspeople could get water. But<br />

the sign advertising Coca-Cola<br />

signals a more modern era.<br />

1 8 — T H E G R E A T D E P R E S S I O N T R A N S F O R M S M O N T A N A 3 6 9

3 7 0 P A R T 3 : W A V E S O F D E V E L O P M E N T<br />

liberal representatives to Congress. This was because they knew that<br />

conservative state politicians would spend less money, promote business<br />

activity, and help businesses grow. But liberal administrations in<br />

Washington, D.C., usually sponsored more generous federal aid programs,<br />

so it paid to send liberals to Washington. This somewhat odd pattern<br />

began in the early 1900s and lasted through most of the century.<br />

War in Europe Revives<br />

the Nation’s Economy<br />

Roosevelt’s New Deal did not end the Great Depression. It did keep<br />

thousands of <strong>Montana</strong>ns alive, employed, and fed through the toughest<br />

years. It gave people meaningful work that improved their communities.<br />

And it helped people recover hope in the future and pride in<br />

themselves.<br />

What ended the Great Depression was war. In 1939 Germany invaded<br />

Poland. France and England declared war on Germany. America’s participation<br />

in World War II dramatically revived the <strong>Montana</strong> economy.<br />

Just as in World War I, the United States supported its allies with food<br />

and supplies. New military contracts for metals, lumber, wheat, and oil<br />

activated the economy. <strong>Montana</strong>’s industries boomed again.<br />

The next fi ve years brought record profi ts to farmers, ranchers,<br />

and other <strong>Montana</strong> industries. And they brought a turning point in<br />

<strong>Montana</strong> history.<br />

FIGURE 18.19: With crops in the ground and food on the table, many <strong>Montana</strong>ns once<br />

again felt secure and hopeful about the future.

Expressions of the People<br />

<strong>Montana</strong>’s Post<br />

Offi ce Murals<br />

During the Great Depression, President Franklin Roosevelt<br />

wanted to create jobs, lift people’s spirits, and give Americans<br />

“a more abundant life.” One way was to hire artists<br />

to create and install art in public places.<br />

Between 1937 and 1942 the government hired <strong>Montana</strong><br />

artists to paint murals for six <strong>Montana</strong> post offi ces—in Dillon,<br />

Deer Lodge, Sidney, Hamilton, Billings, and Glasgow. Post<br />

offi ces were community gathering places<br />

where people frequently stopped to visit<br />

and do business. They made a natural choice<br />

for public art projects.<br />

The government often asked artists to<br />

paint scenes from local history. The murals<br />

emphasized themes that would appeal to the<br />

whole community. Painter Elizabeth Lochrie<br />

chose to depict a varied group of Indians,<br />

cowboys, and travelers gathered around a<br />

mailbox in Frying Pan Basin, along the stage<br />

route between Dillon and Butte. Her painting,<br />

News from the States, emphasized the<br />

importance of mail from the outside during<br />

the early territorial days.<br />

Artist Henry Meloy painted Flathead War<br />

Party for the Hamilton post offi ce, showing a<br />

war party preparing to attack the Blackfeet,<br />

with Mount Como in the background. For<br />

FIGURE 18.20: <strong>Montana</strong> painter<br />

Elizabeth Lochrie smiles at the<br />

camera while she and two unidentifi ed<br />

assistants install her mural, News from<br />

the States, in Dillon. Postmaster Harry<br />

Andrus, on the fl oor, was a great fan<br />

of Lochrie’s work.

FIGURE 18.21: <strong>Montana</strong> artist Henry Meloy<br />

(1902–1951) was born in <strong>To</strong>wnsend. He<br />

studied art in Chicago and New York and<br />

later taught art at Columbia University.<br />

His mural, Flathead War Party, shows the<br />

tribe getting ready to attack the Blackfeet<br />

in the Bitterroot Valley.<br />

the Deer Lodge post offi ce, Verona Burkhard painted James<br />

and Granville Stuart Prospecting in Deer Lodge Valley—1858.<br />

<strong>To</strong>wnspeople watched the artists’ progress as they stopped<br />

<strong>by</strong> the post offi ce to pick up mail each day. Sometimes they<br />

commented on the paintings. In Glasgow a women’s group<br />

complained about artist Forrest Hill’s painting, Early Settlers<br />

and Residents and Modern Industries. The painting originally<br />

included a gambler drinking whiskey. But after intense<br />

pressure from the women’s group, Hill painted in a woman<br />

carrying a Bible instead.<br />

But usually the paintings excited locals. Verona Burkhard<br />

wrote to the local postmaster, “People of Deer Lodge surprised<br />

me <strong>by</strong> their great interest in the mural.”<br />

Painter Leo Beaulaurier, who created a mural in the Billings<br />

post offi ce, said the program was a great help to <strong>Montana</strong><br />

artists. “It was a hard time for the arts,” he said. “People could<br />

barely afford necessities, much less paintings.”<br />

<strong>To</strong>day all six post offi ce murals still hang in their original<br />

spots. Five of the six have been cleaned and restored. These<br />

paintings capture important moments in <strong>Montana</strong> history.<br />

They also remind <strong>Montana</strong>ns how important public art can<br />

be—in good times and bad.

CHECK FOR UNDERSTANDING<br />

1. Identify: (a) New Deal; (b) National Industrial<br />

Recovery Act; (c) Meriam Report; (d) Indian<br />

Reorganization Act<br />

2. Defi ne: (a) initiative; (b) malnourished; (c) work<br />

relief; (d) infrastructure; (e) subsidies; (f) pension;<br />

(g) bureaucratic; (h) conservative; (i) liberal<br />

3. Why did hard economic times arrive earlier in<br />

<strong>Montana</strong> than in the rest of the nation?<br />

4. What hopeful, if short-lived, sign of better times<br />

occurred in the mid-1920s?<br />

5. What major <strong>Montana</strong> industries were affected <strong>by</strong><br />

the stock market crash of 1929?<br />

6. Why were people in rural areas better able<br />

to cope during the early years of the Great<br />

Depression than people in cities?<br />

7. What was one of the main issues of the 1932<br />

presidential election?<br />

8. Describe the three goals of the New Deal.<br />

9. How did the New Deal help people living on<br />

10.<br />

11.<br />

12.<br />

13.<br />

14.<br />

15.<br />

16.<br />

reservations?<br />

How did the Fort Peck Dam project boost<br />

<strong>Montana</strong>’s economy?<br />

What federal legislation made it easier for<br />

Anaconda Copper Mining Company employees<br />

to organize unions?<br />

What did the Meriam Report conclude about<br />

federal Indian policy?<br />

Describe the Indian Reorganization Act.<br />

Why did some Indians disagree with parts of the<br />

Indian Reorganization Act?<br />

What are some of the main differences between<br />

liberals and conservatives?<br />

What international event helped end the Great<br />

Depression?<br />

CRITICAL THINKING<br />

1. Think about the reasons the text gives to<br />

explain why some tribes opposed the Indian<br />

Reorganization Act. Do you think these are<br />

understandable concerns and disagreements?<br />

Why or why not?<br />

2. How did the presidential candidates of 1932<br />

refl ect the traditional viewpoints of conservatives<br />

and liberals?<br />

3. Look at the map on page 359. Which counties<br />

were hardest hit <strong>by</strong> the Depression? Which were<br />

the least affected? Form a hypothesis to explain<br />

your fi ndings. What further research could you<br />

undertake to test your theory?<br />

4. If you had been an eastern <strong>Montana</strong> farmer<br />

during the 1930s, do you think you would have<br />

wanted to stay on your farm? What would you<br />

lose <strong>by</strong> leaving? What would you gain?<br />

CHAPTER 18 REVIEW<br />

PAST TO PRESENT<br />

1. The government programs put in place to help<br />

people during the Great Depression were wildly<br />

popular. <strong>To</strong>day, programs aimed at helping the<br />

poor sometimes generate more controversy.<br />

What accounts for this change in attitude?<br />

2. Do you think <strong>Montana</strong> could experience such<br />

hard economic times again? Why or why not?<br />

MAKE IT LOCAL<br />

1. What organized charities exist in your<br />

hometown? Are these charities able to help<br />

everyone in need?<br />

EXTENSION ACTIVITIES<br />

1. Research the building of the Fort Peck Dam.<br />

Create a poster or PowerPoint presentation on<br />

one aspect of the dam’s story.<br />

2. Learn more about the New Deal work programs<br />

(the CCC and the WPA). What permanent<br />

projects did they create? What nonpermanent<br />

services did they provide?<br />

3. Research some of the arts projects created under<br />

the Works Progress Administration. Compare<br />

these projects with projects produced <strong>by</strong> the<br />

National Endowment for the Arts. Analyze<br />

the differences and similarities between these<br />

programs and then debate their worth to society.<br />

4. The Farm Security Administration (a New Deal<br />

program) sent four photographers to <strong>Montana</strong><br />

as part of a larger documentary photography<br />

project. Research the project and analyze some of<br />

its <strong>Montana</strong> images. Then update the FSA project<br />

<strong>by</strong> creating a photography project to document<br />

your community today.<br />

5. Write a diary entry or letter, set during the 1930s,<br />

from one of the following points of view: an<br />

eastern <strong>Montana</strong> farmer; an Indian living on a<br />

<strong>Montana</strong> reservation; a worker on the Fort Peck<br />

Dam project; an artist hired to paint a post offi ce<br />

mural; or a young man from the city who has<br />

taken a job with the CCC in the national forest.<br />

6. The New Deal increased <strong>Montana</strong>’s dependence<br />

on the federal government. Research the<br />

federal presence in <strong>Montana</strong> today, including<br />

the amount of federal money spent in the state.<br />

Discuss the pros and cons of this situation.<br />

1 8 — T H E G R E A T D E P R E S S I O N T R A N S F O R M S M O N T A N A 3 7 3

Credits<br />

The following abbreviations are used in the credits:<br />

BBHC Buffalo Bill <strong>Historical</strong> Center, Cody, Wyoming<br />

GNPA Glacier National Park Archives<br />

LOC Library of Congress<br />

MAC <strong>Montana</strong> Arts Council, Helena<br />

MDEQ <strong>Montana</strong> Department of Environmental Quality, Helena<br />

MDT <strong>Montana</strong> Department of Transportation, Helena<br />

MFWP <strong>Montana</strong> Fish, Wildlife and Parks, Helena<br />

MHS <strong>Montana</strong> <strong>Historical</strong> <strong>Society</strong>, Helena<br />

MHSA <strong>Montana</strong> <strong>Historical</strong> <strong>Society</strong> Archives, Helena<br />

MHSL <strong>Montana</strong> <strong>Historical</strong> <strong>Society</strong> Library, Helena<br />

MHS Mus. <strong>Montana</strong> <strong>Historical</strong> <strong>Society</strong> Museum, Helena<br />

MHS PA <strong>Montana</strong> <strong>Historical</strong> <strong>Society</strong> Photograph Archives, Helena<br />

MSU COT <strong>Montana</strong> State University College of Technology, Billings<br />

NMAI National Museum American Indian, Smithsonian Institution,<br />

Washington, D.C.<br />

MSU Billings Special Collections, <strong>Montana</strong> State University<br />

Billings Library<br />

NARA National Archives and Records Administration<br />

NPS National Park Service<br />

NRIS Natural Resource Information System, <strong>Montana</strong> State<br />

Library, Helena<br />

SHPO State Historic Preservation Offi ce, <strong>Montana</strong> <strong>Historical</strong><br />

<strong>Society</strong>, Helena<br />

TM Travel <strong>Montana</strong>, Helena<br />

UM Missoula Archives & Special Collections, The University<br />

of <strong>Montana</strong>-Missoula<br />

USDA United States Department of Agriculture<br />

USFS United States Forest Service<br />

WMM World Museum of Mining, Butte<br />

Chapter 18<br />

fig. 18.1 <strong>No</strong> <strong>Place</strong> to <strong>Go</strong>, <strong>Maynard</strong> <strong>Dixon</strong>, <strong>1935</strong>, oil on canvas, 251 ⁄8 x 30<br />

inches, courtesy Brigham Young University Museum of Art,<br />

part of Harold R. Clark Memorial Collection<br />

fig. 18.2 Charles McKenzie’s sheep ranch, Garfi eld County, photo <strong>by</strong><br />

John Vachon, 1942, courtesy LOC LC-USF34-064965-D<br />

fig. 18.3 Mrs. Ballinger, Flathead Valley, photo <strong>by</strong> John Vachon, 1942,<br />

courtesy LOC LC-USF34-065186-D<br />

fig. 18.4 Cricket traps, Big Horn County, photo <strong>by</strong> Arthur Rothstein,<br />

1939, courtesy LOC LC-USF34-027411-D<br />

fig. 18.5 Salvation Army, Butte, <strong>1935</strong>, photo <strong>by</strong> L. H. Jorud, MHS PA<br />

PAc 74-37<br />

fig. 18.6 Oregon or Bust, near Missoula, photo <strong>by</strong> Arthur Rothstein,<br />

1936, courtesy LOC LC-USF34-005008-D<br />

fig. 18.7 Percentage of <strong>Montana</strong>ns on relief <strong>by</strong> county, <strong>1935</strong>,<br />

map <strong>by</strong> MHS with information from Carol F. Kraenzel and<br />

Ruth B. McIntosh, The Relief Problem in <strong>Montana</strong>: A Study of the<br />

Change in the Character of the Relief Population, bulletin no. 343<br />

(Bozeman, 1937), p. 10<br />

fig. 18.8 L-R: F. D. R. with Col. T. B. Larkin, District Engineer, and<br />

George H. Dern, Secretary of War, Fort Peck Dam, 1934, MHS PA<br />

fig. 18.9 WPA Bookmobile, Fairfi eld, MHS PA PAc 89-38 F5<br />

fig. 18.10 CCC camp, courtesy Dr. William E. Farr, Missoula<br />

fig. 18.11 Fort Peck Dam, photo <strong>by</strong> Donnie Sexton, courtesy TM<br />

fig. 18.12 Fort Peck Dam construction, 1936, MHS PA<br />

fig. 18.13 Farmer’s daughter in storage cellar, Fairfi eld Bench<br />

Farms, photo <strong>by</strong> Arthur Rothstein, 1939, courtesy LOC<br />

LC-USF34-027311-D<br />

fig. 18.14 Home and car, Butte, photo <strong>by</strong> Russell Lee, 1942,<br />

courtesy LOC LC-USW3-009706-D<br />

fig. 18.15 Men and young boys at Medicine Lodge, courtesy BBHC,<br />

Jack Richard Collection PN.165.2.1<br />

fig. 18.16 Poster, ca. <strong>1935</strong>, MHS Mus. 1980.61.165<br />

fig. 18.17 Anaconda Smelter workers, photo <strong>by</strong> Russell Lee, 1942,<br />

courtesy LOC LC-USW3-008534-D<br />

fig. 18.18 Pool parlor, Fairfi eld, photo <strong>by</strong> Arthur Rothstein, 1939,<br />

courtesy LOC LC-USF33-003106-M4<br />

fig. 18.19 Farm family at dinner, Fairfi eld Bench Farms, photo <strong>by</strong><br />

Arthur Rothstein, 1939, courtesy LOC LC-USF34-027323-D<br />

fig. 18.20 Elizabeth Lochrie installing her mural in Dillon Post Offi ce,<br />

1938, MHS PA PAc 80-61<br />

fig. 18.21 Flathead War Party, mural <strong>by</strong> Henry J. Meloy, Hamilton<br />

Post Offi ce, 1942, photo <strong>by</strong> Don Beatty, 1987, MHS PA