TYPOGRAPHY - IAM

TYPOGRAPHY - IAM

TYPOGRAPHY - IAM

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

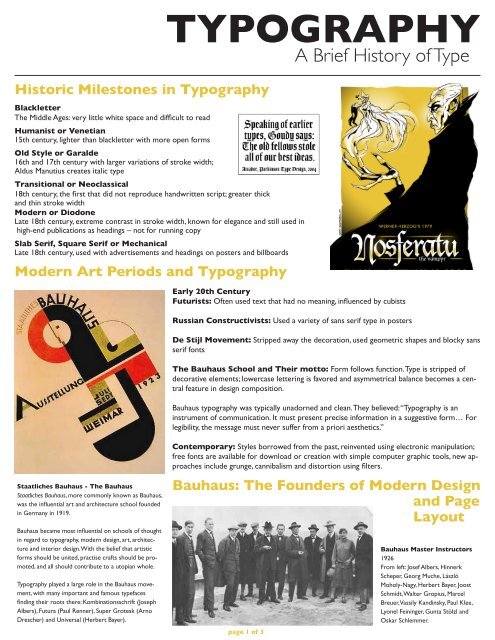

Historic Milestones in Typography<br />

Blackletter<br />

The Middle Ages: very little white space and difficult to read<br />

Humanist or Venetian<br />

15th century, lighter than blackletter with more open forms<br />

Old Style or Garalde<br />

16th and 17th century with larger variations of stroke width;<br />

Aldus Manutius creates italic type<br />

Transitional or Neoclassical<br />

18th century, the first that did not reproduce handwritten script; greater thick<br />

and thin stroke width<br />

Modern or Diodone<br />

Late 18th century, extreme contrast in stroke width, known for elegance and still used in<br />

high-end publications as headings – not for running copy<br />

Slab Serif, Square Serif or Mechanical<br />

Late 18th century, used with advertisements and headings on posters and billboards<br />

Modern Art Periods and Typography<br />

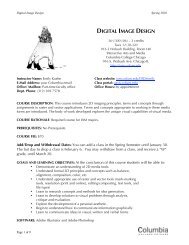

Staatliches Bauhaus - The Bauhaus<br />

Staatliches Bauhaus, more commonly known as Bauhaus,<br />

was the influential art and architecture school founded<br />

in Germany in 1919.<br />

Bauhaus became most influential on schools of thought<br />

in regard to typography, modern design, art, architecture<br />

and interior design. With the belief that artistic<br />

forms should be united, practise crafts should be promoted,<br />

and all should contribute to a utopian whole.<br />

Typography played a large role in the Bauhaus movement,<br />

with many important and famous typefaces<br />

finding their roots there: Kombinationsschrift (Joseph<br />

Albers), Futura (Paul Renner), Super Grotesk (Arno<br />

Drescher) and Universal (Herbert Bayer).<br />

<strong>TYPOGRAPHY</strong><br />

Early 20th Century<br />

Futurists: Often used text that had no meaning, influenced by cubists<br />

Russian Constructivists: Used a variety of sans serif type in posters<br />

De Stijl Movement: Stripped away the decoration, used geometric shapes and blocky sans<br />

serif fonts<br />

The Bauhaus School and Their motto: Form follows function. Type is stripped of<br />

decorative elements; lowercase lettering is favored and asymmetrical balance becomes a central<br />

feature in design composition.<br />

Bauhaus typography was typically unadorned and clean. They believed: “Typography is an<br />

instrument of communication. It must present precise information in a suggestive form… For<br />

legibility, the message must never suffer from a priori aesthetics.”<br />

Contemporary: Styles borrowed from the past, reinvented using electronic manipulation;<br />

free fonts are available for download or creation with simple computer graphic tools, new approaches<br />

include grunge, cannibalism and distortion using filters.<br />

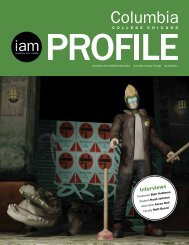

Bauhaus: The Founders of Modern Design<br />

and Page<br />

Layout<br />

page 1 of 3<br />

A Brief History of Type<br />

Bauhaus Master Instructors<br />

1926<br />

From left: Josef Albers, Hinnerk<br />

Scheper, Georg Muche, László<br />

Moholy-Nagy, Herbert Bayer, Joost<br />

Schmidt, Walter Gropius, Marcel<br />

Breuer, Vassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee,<br />

Lyonel Feininger, Gunta Stölzl and<br />

Oskar Schlemmer.

Type Categories Type Relationships Type Contrasts and<br />

Terms<br />

Oldstyle<br />

A serif group based on hand lettering, works<br />

well with large areas of printed text<br />

Modern<br />

Influenced by the Industrial Revolution and<br />

Mechanical Age; advances in advertising. Serifs<br />

are horizontal and very thin. Best in large sizes<br />

for headings and titles. Very low legibility.<br />

Slab Serif<br />

Thick throughout the letter form, easy to see<br />

from afar, on posters, readable for smaller areas<br />

of text with wide leading and often used<br />

for children’s books<br />

Sans Serif<br />

No serifs, come in a variety of different<br />

weights (bold, regular, thin, etc), Easier to read<br />

on screens for large areas of text.<br />

Script<br />

Resembles hand writing where letters connect;<br />

like cursive writing. Not good for large<br />

areas of text, best for small areas of text, logos<br />

or large accents.<br />

Decorative<br />

Fun, distinctive, are best in small quantities and<br />

work great for headlines and small accents.<br />

Some look really awful no matter what!<br />

Concordant<br />

When you only use one type family without<br />

much variation – a safe mix—but can be a bit<br />

dull<br />

Conflicting<br />

When you use different typefaces that are too<br />

similar in size, style, etc. Usually not a good<br />

direction in typography<br />

Contrasting<br />

Using completely different typefaces, which<br />

can be exciting and is a good direction in typography.<br />

NEVER USE MORE THAN THREE<br />

PER PAGE!<br />

Type Spacing<br />

Leading<br />

The horizontal space between one line of text<br />

and the next<br />

Kerning<br />

The space between two letters<br />

Tracking<br />

The spacing across a whole string of letters,<br />

used for decorative purposes<br />

page 2 of 3<br />

Size<br />

Obvious differences in the font size or the use<br />

of large areas of white space<br />

Weight or Style<br />

Thickness of stroke. Some examples include<br />

regular, bold, semibold, extra bold, light, etc.<br />

Using contrasting weights makes a page more<br />

attractive and helps organize content.<br />

Structure<br />

The design of the typeface, such as stroke<br />

width, serif thickness, distance between letters<br />

Form<br />

Refers to how a letter is shaped, such as the<br />

difference between upper case and lower case<br />

of the same typeface<br />

Direction<br />

Refers to the diagonal slant or vertical direction<br />

of the counters.<br />

Type<br />

A printed character or printed characters; an<br />

element in design.<br />

Typeface<br />

The style or design of a font.

Sans Serif History<br />

Egyptian<br />

The term was first used by Joseph Farington<br />

after seeing the sans serif inscription on John<br />

Flaxman’s memorial to Isaac Hawkins Brown<br />

in 1805, although today the term is commonly<br />

used to refer to slab serif, not sans serif.<br />

Antique<br />

In about 1817, the Figgins foundry in London<br />

made a type with square or slab-serifs which<br />

it called ‘Antique’, and that name was adopted<br />

by most of the British and US typefounders.<br />

An exception was the typefounder Thorne,<br />

who confused things by marketing his Antique<br />

under the name ‘Egyptian’. In France it became<br />

Egyptienne, and to worsen the confusion, the<br />

French called sans-serif type ‘Antique’. Some<br />

fonts, such as Antique Olive, still carry the<br />

name.<br />

Grotesque<br />

It was originally coined by William Thorowgood<br />

of Fann Street Foundry, the first person<br />

to produce a sans-serif type with lower case,<br />

in 1832. The name came from the Italian word<br />

‘grottesco’, meaning ‘belonging to the cave’.<br />

In Germany, the name became Grotesk. German<br />

typefounders adopted the term from the<br />

nomenclature of Fann Street Foundry, which<br />

took on the meaning of cave (or grotto) art.<br />

Nevertheless, some explained the term was<br />

derived from the surprising response from<br />

the typographers.<br />

Doric<br />

It was the term first used by H. W. Caslon<br />

Foundry in Chiswell Street in 1870 to describe<br />

various sans-serif fonts at a time the<br />

generic name ‘sans-serif’ was commonly accepted.<br />

Eventually the foundry used Sans-serif<br />

in 1906. At that time, Doric referred to a certain<br />

kind of stressed sans-serif types.<br />

Gothic<br />

Not to be confused with blackletter typeface,<br />

the term was used mainly by American type<br />

founders.The term probably derived from<br />

the architectural definition, which is neither<br />

Greek or Roman;and from the extended adjective<br />

term of ‘Germany’, which was the place<br />

where sans-serif typefaces became popular in<br />

19th to 20th century.[13] Early adopters for<br />

the term includes Miller & Richard (1863), J.<br />

& R. M. Wood (1865), Lothian, Conner, Bruce<br />

McKellar. Although the usage is now rare in<br />

the English-speaking world, the term is commonly<br />

used in Japan and South Korea.<br />

Classification<br />

For the purposes of type classification, sansserif<br />

designs can be divided into four major<br />

groups:<br />

Grotesque<br />

Early sans-serif designs, such as Grotesque,<br />

Akzidenz Grotesk, and Franklin Gothic.<br />

Digital Types<br />

of Fonts<br />

Postscript Type 1<br />

Developed by Adobe, these consist of a printer<br />

or outline font, a screen or bitmap font, and<br />

usually a font metrics file (.afm). Type 1 fonts<br />

are considered the high-quality standard for<br />

years, although OpenType is changing that.<br />

TrueType<br />

Developed by Apple and MicroSoft, TrueType<br />

was to replace Type1 font standards.<br />

TrueType consists of a single file and more<br />

commonly used on Windows computers.<br />

Multiple Master<br />

Developed by Adobe, Multiple Master fonts<br />

were intended to give the designer creative<br />

freedom to scale fonts to custom widths and<br />

weights. They are similar to Type 1 fonts.<br />

Adobe no longer supports these fonts.<br />

OpenType<br />

Developed by Adobe and MicroSoft, Open-<br />

Type is a universal font format that includes<br />

the benefits of Type 1 fonts and TrueType font<br />

technologies. It is Unicode compliant, is crossplatform,<br />

and consists of a single font file.<br />

Neo-grotesque or Transitional<br />

or Realist<br />

Modern designs such as Standard, Bell Centennial,<br />

MS Sans Serif, Helvetica, Univers,<br />

Highway Gothic, and Arial. These are the most<br />

common sans-serif fonts. They are relatively<br />

straight in appearance and have less line width<br />

variation than Humanist sans-serif typefaces.<br />

Transitional sans-serif is sometimes called<br />

“anonymous sans-serif” due to its relatively<br />

plain appearance.<br />

Humanist<br />

Calibri, Johnston, Lucida Grande, Segoe UI, Gill<br />

Sans, Myriad, Frutiger, Trebuchet MS, Tahoma,<br />

Verdana and Optima. These are the most calligraphic<br />

of the sans-serif typefaces, with some<br />

variation in line width and more legibility than<br />

other sans-serif fonts.<br />

Geometric<br />

Futura, ITC Avant Garde, Century Gothic,<br />

Gotham, or Spartan. As their name suggests,<br />

Geometric sans-serif typefaces are based on<br />

geometric shapes. Note the optically circular<br />

letter “O” and the simple construction of<br />

the lowercase letter “a”. Geometric sans-serif<br />

fonts have a very modern look and feel. Of<br />

these four categories, geometric fonts tend to<br />

be the least useful for body text.<br />

Note that in some sans-serif fonts, such as<br />

Arial, the capital-i and lowercase-L appear<br />

identical. Verdana, however, keeps them distinct<br />

because Verdana’s capital-i, as an exception,<br />

has serifs. Other fonts may have two<br />

horizontal bars on the capital-i, a curved tail<br />

on the lowercase-L, or both.<br />

page 3 of 3<br />

For Your<br />

Viewers<br />

Legibility<br />

How easy it is to distinguish one letter<br />

from another in a particular typeface.<br />

• Doesn’t call too much attention to<br />

itself<br />

• Has good contrast<br />

• Has a larger x-height and little<br />

variation in stroke width<br />

• Has easy to recognize characteristics<br />

• Isn’t too bold or light<br />

• Does not use all caps or caps on each<br />

word in a headline<br />

Readability<br />

The ease with which a reader can scan<br />

over paragraphs of type.<br />

• Line lengths<br />

• Point size<br />

• Leading<br />

• Typeface selection<br />

• Type alignment<br />

• Background content<br />

British Standards<br />

classification<br />

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vox-ATypI_classification<br />

(scroll down for examples)<br />

Grotesque<br />

Lineale typefaces with 19th century origins.<br />

There is some contrast in thickness of strokes.<br />

They have squareness of curve, and curling<br />

close-set jaws. The R usually has a curled leg<br />

and the G is spurred. The ends of the curved<br />

strokes are usually horizontal. Examples include<br />

Stephenson Blake Grotesque No. 6,<br />

Condensed Sans No. 7, Monotype Headline<br />

Bold.<br />

Neo-grotesque<br />

Lineale typefaces derived from the grotesque.<br />

They have less stroke contrast and are more<br />

regular in design. The jaws are more open<br />

than in the true grotesque and the g is often<br />

open-tailed. The ends of the curved strokes<br />

are usually oblique. Examples include Edel/<br />

Wotan, Univers, Helvetica.<br />

Geometric<br />

Lineale typefaces constructed on simple geometric<br />

shapes, circle or rectangle. Usually<br />

monoline, and often with single-storey a. Examples<br />

include Futura, Erbar, Eurostile.<br />

Humanist<br />

Lineale typefaces based on the proportions of<br />

inscriptional Roman capitals and Humanist or<br />

Garalde lower-case, rather than on early grotesques.<br />

They have some stroke contrast, with<br />

two-storey a and g. Examples include Optima,<br />

Gill Sans, Pascal.