Pt Two

Pt Two

Pt Two

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

UNIT NINE: Late Baroque and Rococo STUDY GUIDE<br />

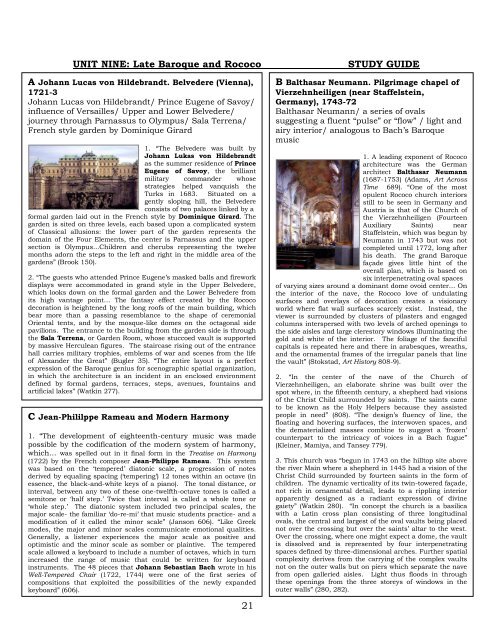

A Johann Lucas von Hildebrandt. Belvedere (Vienna),<br />

1721-3<br />

Johann Lucas von Hildebrandt/ Prince Eugene of Savoy/<br />

influence of Versailles/ Upper and Lower Belvedere/<br />

journey through Parnassus to Olympus/ Sala Terrena/<br />

French style garden by Dominique Girard<br />

1. “The Belvedere was built by<br />

Johann Lukas von Hildebrandt<br />

as the summer residence of Prince<br />

Eugene of Savoy, the brilliant<br />

military commander whose<br />

strategies helped vanquish the<br />

Turks in 1683. Situated on a<br />

gently sloping hill, the Belvedere<br />

consists of two palaces linked by a<br />

formal garden laid out in the French style by Dominique Girard. The<br />

garden is sited on three levels, each based upon a complicated system<br />

of Classical allusions: the lower part of the garden represents the<br />

domain of the Four Elements, the center is Parnassus and the upper<br />

section is Olympus...Children and cherubs representing the twelve<br />

months adorn the steps to the left and right in the middle area of the<br />

gardens” (Brook 150).<br />

2. “The guests who attended Prince Eugene‟s masked balls and firework<br />

displays were accommodated in grand style in the Upper Belvedere,<br />

which looks down on the formal garden and the Lower Belvedere from<br />

its high vantage point… The fantasy effect created by the Rococo<br />

decoration is heightened by the long roofs of the main building, which<br />

bear more than a passing resemblance to the shape of ceremonial<br />

Oriental tents, and by the mosque-like domes on the octagonal side<br />

pavilions. The entrance to the building from the garden side is through<br />

the Sala Terrena, or Garden Room, whose stuccoed vault is supported<br />

by massive Herculean figures. The staircase rising out of the entrance<br />

hall carries military trophies, emblems of war and scenes from the life<br />

of Alexander the Great” (Bugler 35). “The entire layout is a perfect<br />

expression of the Baroque genius for scenographic spatial organization,<br />

in which the architecture is an incident in an enclosed environment<br />

defined by formal gardens, terraces, steps, avenues, fountains and<br />

artificial lakes” (Watkin 277).<br />

C Jean-Phililppe Rameau and Modern Harmony<br />

1. “The development of eighteenth-century music was made<br />

possible by the codification of the modern system of harmony,<br />

which… was spelled out in it final form in the Treatise on Harmony<br />

(1722) by the French composer Jean-Philippe Rameau. This system<br />

was based on the „tempered‟ diatonic scale, a progression of notes<br />

derived by equaling spacing („tempering‟) 12 tones within an octave (in<br />

essence, the black-and-white keys of a piano). The tonal distance, or<br />

interval, between any two of these one-twelfth-octave tones is called a<br />

semitone or „half step.‟ Twice that interval is called a whole tone or<br />

„whole step.‟ The diatonic system included two principal scales, the<br />

major scale- the familiar „do-re-mi‟ that music students practice- and a<br />

modification of it called the minor scale” (Janson 606). “Like Greek<br />

modes, the major and minor scales communicate emotional qualities.<br />

Generally, a listener experiences the major scale as positive and<br />

optimistic and the minor scale as somber or plaintive. The tempered<br />

scale allowed a keyboard to include a number of octaves, which in turn<br />

increased the range of music that could be written for keyboard<br />

instruments. The 48 pieces that Johann Sebastian Bach wrote in his<br />

Well-Tempered Chair (1722, 1744) were one of the first series of<br />

compositions that exploited the possibilities of the newly expanded<br />

keyboard” (606).<br />

21<br />

B Balthasar Neumann. Pilgrimage chapel of<br />

Vierzehnheiligen (near Staffelstein,<br />

Germany), 1743-72<br />

Balthasar Neumann/ a series of ovals<br />

suggesting a fluent “pulse” or “flow” / light and<br />

airy interior/ analogous to Bach‟s Baroque<br />

music<br />

1. A leading exponent of Rococo<br />

architecture was the German<br />

architect Balthasar Neumann<br />

(1687-1753) (Adams, Art Across<br />

Time 689). “One of the most<br />

opulent Rococo church interiors<br />

still to be seen in Germany and<br />

Austria is that of the Church of<br />

the Vierzehnheiligen (Fourteen<br />

Auxiliary Saints) near<br />

Staffelstein, which was begun by<br />

Neumann in 1743 but was not<br />

completed until 1772, long after<br />

his death. The grand Baroque<br />

façade gives little hint of the<br />

overall plan, which is based on<br />

six interpenetrating oval spaces<br />

of varying sizes around a dominant dome ovoid center… On<br />

the interior of the nave, the Rococo love of undulating<br />

surfaces and overlays of decoration creates a visionary<br />

world where flat wall surfaces scarcely exist. Instead, the<br />

viewer is surrounded by clusters of pilasters and engaged<br />

columns interspersed with two levels of arched openings to<br />

the side aisles and large clerestory windows illuminating the<br />

gold and white of the interior. The foliage of the fanciful<br />

capitals is repeated here and there in arabesques, wreaths,<br />

and the ornamental frames of the irregular panels that line<br />

the vault” (Stokstad, Art History 808-9).<br />

2. “In the center of the nave of the Church of<br />

Vierzehnheiligen, an elaborate shrine was built over the<br />

spot where, in the fifteenth century, a shepherd had visions<br />

of the Christ Child surrounded by saints. The saints came<br />

to be known as the Holy Helpers because they assisted<br />

people in need” (808). “The design‟s fluency of line, the<br />

floating and hovering surfaces, the interwoven spaces, and<br />

the dematerialized masses combine to suggest a „frozen‟<br />

counterpart to the intricacy of voices in a Bach fugue”<br />

(Kleiner, Mamiya, and Tansey 779).<br />

3. This church was “begun in 1743 on the hilltop site above<br />

the river Main where a shepherd in 1445 had a vision of the<br />

Christ Child surrounded by fourteen saints in the form of<br />

children. The dynamic verticality of its twin-towered façade,<br />

not rich in ornamental detail, leads to a rippling interior<br />

apparently designed as a radiant expression of divine<br />

gaiety” (Watkin 280). “In concept the church is a basilica<br />

with a Latin cross plan consisting of three longitudinal<br />

ovals, the central and largest of the oval vaults being placed<br />

not over the crossing but over the saints‟ altar to the west.<br />

Over the crossing, where one might expect a dome, the vault<br />

is dissolved and is represented by four interpenetrating<br />

spaces defined by three-dimensional arches. Further spatial<br />

complexity derives from the carrying of the complex vaults<br />

not on the outer walls but on piers which separate the nave<br />

from open galleried aisles. Light thus floods in through<br />

these openings from the three storeys of windows in the<br />

outer walls” (280, 282).

UNIT NINE: Late Baroque and Rococo STUDY GUIDE<br />

D Giovanni Battista Tiepolo. The Banquet of Cleopatra (Palazzo Labia, Venice), 1746-50, fresco<br />

Giovanni Battista Tiepolo/ Antony and Cleopatra/ a pearl for dessert/ luxury and the Labia family in Venice/<br />

Tiepolo and Mengozzi Colonna / trompe l‟oeil architectural details<br />

1. “The ceilings of Late Baroque palaces sometimes became painted festivals for the<br />

imagination. The master of such works, Giambattista Tiepolo (1696-1770), was the last<br />

great Italian painter to have an international impact until the twentieth century” (Kleiner,<br />

Mamiya, and Tansey 780). Between 1746 and 1750, Tiepolo and his assistants decorated a<br />

banqueting-hall for the noble Labia family in Venice. The work, covering 500 square meters, tells the<br />

story of Cleopatra. In this particular fresco, “spellbound, the assembled guests gaze at a woman<br />

about the redeem a wager. Cleopatra VII, Queen of Egypt, had boasted the Roman general, Antony,<br />

that she could devour a hundred times one hundred thousand sesterces at one meal… The Roman<br />

author Pliny the Elder, writing during the first century after Christ, had described the scene in his<br />

Natural History. Cleopatra, according to Pliny, had served up a banquet which, though sumptuous,<br />

amounted to little more than one of their everyday meals. Seeing this, Antony had merely laughed<br />

and asked to see the bill. Cleopatra had then assured Antony that he had seen no more than the<br />

trimmings, whereas the feast to come would certainly cost the agreed amount. She had then ordered<br />

dessert. However, the servants had placed before her only a single dish, filled with vinegar,<br />

whereupon the queen had removed one of her earrings, dipped it into the vinegar, let it dissolve, and<br />

swallowed it” (Hagen and Hagen, What Great Paintings Say 1: 116).<br />

2. “Tiepolo‟s contemporaries were probably in a better position than Pliny to appreciate Cleopatra‟s<br />

lifestyle. The Venetian Republic had lost most of its political and military power by the 18 th century.<br />

At the same time, its citizens attempted to make up for their sense of loss by squandering the vast<br />

wealth they had accumulated during their glorious past… During the 17 th century, when the<br />

maritime republic had been desperate for money to fight the Turks, the Labia had used the<br />

opportunity to buy their way into Venice‟s exclusive patrician circles. A legendary act of extravagance<br />

won them a mention in the annals of the town: at the climax of a banquet for 40 persons, a Labia, expressing violent contempt for all<br />

material possessions, had commanded the golden plates from which the guests had just finished eating to be thrown out of the window<br />

into the canal. In choosing the extravagant Egyptian queen as the subject of their banquet hall frescoes, the Labia were attempting to<br />

establish their own, admittedly rather tongue-in-cheek relation to tradition” (118). “But all that glitters is not gold… Thus it is said that<br />

the Labia recovered their costly plates by means of underwater nets stretched out in front of the palazzo. As for Cleopatra, chemistry had<br />

proved that pearls do not dissolve in vinegar!” (118) “The naturalist Pliny gives pearls the highest place among all things of value, but he<br />

also accuses the „family of shells‟ of thereby encouraging indulgence and moral degeneracy… Such are the thoughts of a strict moralist<br />

who cherished plainness and severity, the virtues of a male-dominated, highly militarized society. The Romans castigated luxury, selfindulgence<br />

and extravagance” (118).<br />

3. “In Tiepolo‟s day, a Labia widow and her two sons lived in the palace. De Brosses describes here as a woman who, though no longer<br />

young, „was once very beautiful, and had many love affairs.‟ Like the Egyptian queen, she had a famous collection of jewels which she was<br />

proud to show to visitors. Tiepolo would often make flattering allusions to his patrons in his paintings. His majestic portrait of Cleopatra<br />

may therefore bear some resemblance to the lady of the house” (119). “The master and his assistants appear in the background as<br />

discreet observers of the banquet they have painted… The man with the roundish face is said to be Girolamo Mengozzi Colonna (c.<br />

1688-1766), an expert in painting architecture… The entire, sumptuous majesty of the stately room is a masterpiece of trompe l’oeil”<br />

decoration” (120).<br />

4. “The Labia family would have been rich enough to panel their banqueting-hall with real marble if they had wished, or to decorate it with<br />

solid marble columns. It is possible, in any case, that this would have proved cheaper. But they were probably more fond of illusion than<br />

reality. After all, there were marble columns everywhere in Italy, whereas Tiepolo‟s architectural illusions were something quite exclusive:<br />

a highly skilled and baffling artifice which amused visiting spectators… Walls paneled with real marble might have demonstrated wealth,<br />

but they could never have achieved what Tiepolo and Mengozzi enacted with such apparent ease: the extension of space into an<br />

imaginative seascape under a vast evening sky” (121). “Tiepolo‟s contemporaries, it seems, were only too happy to retire from the gray<br />

demands of reality. Angelo-Maria Labia, for example, the widow‟s eldest son, became an abbé- a very worldly ecclesiastic – in order to<br />

escape the troublesome duties of a Venetian noble. As an abbé, he was not required to take office, but could devote his time to renovating<br />

palaces, collecting paintings and commissioning frescoes. His contemporaries spent their time at the theatres, opera houses or the<br />

carnival, and aristocratic tourists from all over Europe came to Venice to partake in what was essentially a non-stop orgy of escapism”<br />

(121).<br />

5. “The table for Cleopatra‟s banquet is laid out in front of a portico, behind which the sails of the Roman fleet are visible. The somewhat<br />

static ordering of the main figures is relaxed by the ironic positioning in the foreground of the little dog and the dwarf, who drags himself<br />

with difficulty up the steps towards the table. Cleopatra‟s exposed décolleté is meant as a reference to the by now advanced stage of her<br />

relationship with Anthony. In contrast to the Melbourne picture, the erotic and witty interpretation of historical events is given<br />

prominence over the festive setting itself” (Eschenfelder 64). “The Labia family were of Spanish origin and had only recently joined the<br />

Venetian patriciate. Tiepolo‟s frescoes reflect the family‟s great desire to create an impression: they are the greatest secular decoration he<br />

ever produced in Venice. The great hall of the palace, which rises up two storeys, is entirely covered by frescoes” (64, 67). “The musicians<br />

on the balcony in the background are an extension of the banqueting scene. Yet, like the fictive architecture, they could just as well be<br />

part of the courtly celebrations taking place in the Palazzo Labia itself” (67).<br />

22

UNIT NINE: Late Baroque and Rococo STUDY GUIDE<br />

E Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz<br />

1. “Profound religious questions had been<br />

raised by Newton‟s mechanistic model of the<br />

universe and by Locke‟s empirical<br />

interpretation of the mind. One<br />

eighteenth-century thinker who<br />

addressed the new religious concerns<br />

was the German intellectual Gottfried<br />

Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716). A<br />

student of jurisprudence, an emissary of<br />

diplomacy, and a mathematician as well as<br />

a philosopher, Leibniz shared with Newton<br />

the honor for the invention of calculus”<br />

(Wren 2: 185).<br />

2. “An idealist, Leibniz regarded<br />

philosophy as an interpretation of<br />

divine thought. For him, human reason<br />

was the imitation of the logic of God.<br />

Reason, therefore, had an authority<br />

independent of experience. Opposed alike<br />

to the pantheism of Spinoza and the<br />

empiricism of Locke, Leibniz built up an<br />

interpretation of the universe on a theory of<br />

matter known as „monadology.‟ Monads,<br />

for Leibniz, were centers of force and<br />

consciousness that were capable of action<br />

and perception. The soul was considered<br />

by Leibniz to be a monad that had<br />

consciousness of itself” (185).<br />

3. “Leibniz outlined his religious beliefs in a<br />

text entitled Theodicy (1710). The keynote<br />

of Leibniz‟s thought was optimism.<br />

Believing in a predetermined harmony<br />

between the activities of the human soul<br />

and body, Leibniz taught that of infinite<br />

possible worlds, God had created the best.<br />

In this theory, the soul is absolutely free<br />

from all external constraint, and its<br />

immortality is guaranteed by the fact of its<br />

independence and imperishable<br />

individuality. In theology, Leibniz argued<br />

the rational possibility of revelation and<br />

miracles. In ethics, he believed that<br />

contemplation should be directed to the<br />

beauty and perfection of the future life, and<br />

that piety should be hopeful and serene.<br />

The great moral teachers of the past had<br />

each, in his view, been awarded a share of<br />

truth; with the selection of the best of them,<br />

philosophy became eclectic and continued<br />

progress toward a permanent and satisfying<br />

interpretation of life” (185).<br />

4. “The optimism that Leibniz expressed in<br />

his philosophical speculations about God<br />

and the universe is reflected in eighteenthcentury<br />

architecture. Churches such as<br />

Vierzehnheiligen … abound in light and<br />

gaiety. Somber intensity of feeling is<br />

dissolved into a brilliantly lit interior in<br />

which decorative flights of fancy delight the<br />

imagination of the viewer” (185-6).<br />

F Antoine Watteau. Return from Cythera, 1717-19, oil on canvas<br />

Antoine Watteau/ “Poussinistes” vs. “Rubenistes”/ Rococo art/ fete<br />

galante/ glowing sky with putti/ love conquers all/ rises and falls<br />

analogous to music / theatrical foliage/ flirtatious gestures/ influence<br />

of Rubens<br />

1. Toward the end of the seventeenth<br />

century, the members of the French<br />

Academy “formed two factions over the<br />

issue of drawing versus color: the<br />

„Poussinistes (or conservatives) against<br />

the Rubenistes. The conservatives<br />

defended Poussin‟s view that drawing,<br />

which appealed to the mind, was superior<br />

to color, which appealed to the senses”<br />

(Janson 594). “Jean-Antoine Watteau<br />

(1684-1721), a Flemish artist living in<br />

Paris, epitomizes the French Rococo<br />

style. He created a new type of painting when he submitted his official examination<br />

painting, The Departure from Cythera, for admission to membership in the Royal<br />

Academy of Painting and Sculpture in 1717. The academicians accepted the painting<br />

in a new category, the fete galante, or elegant outdoor entertainment. The Departure<br />

from Cythera depicts a dreamworld in which beautifully dressed couples, abetted by<br />

putti, take leave of the mythical island of love. The verdant landscape would never soil<br />

the characters‟ exquisite satins and velvets, nor would a summer shower ever threaten<br />

them. This kind of idyllic vision, with its overtones of wistful melancholy, had a<br />

powerful attraction in early-eighteenth-century Paris and soon charmed the rest of<br />

Europe” (Stokstad, Art History 810).<br />

2. “Is this fanciful outing ending or about to begin? The French title Pelerinage a l’ile de<br />

Cytherere has been translated as both Pilgrimage to and Pilgrimage on the Isle of<br />

Cythera, since it has never been determined whether or not the bucolic setting<br />

represents the mythical island of Venus. Watteau‟s objective appears to be not to tell a<br />

story but to induce the poignant and wistful evocation of love” (810). “Watteau leads the<br />

eye from right to left along the curving line, which rises and falls like a phrase of music.<br />

Note also how he breaks the rhythm at the highest point with the man holding the<br />

cane. This breaking of rhythm is a technique also used in music.” (Cumming,<br />

Annotated Art 61) “The sky and foliage act as a theatrical backdrop to a stage set-<br />

Watteau was actively involved in the theater and had many actor friends.” (61) In the<br />

picture, a girl “plays with her fan- the way fans were held or moved was part of a secret<br />

language though which lovers (who were often strictly chaperoned) communicated with<br />

each other” (61). “Watteau painted the embarkation for Cythera at least three times.<br />

The first, somewhat stilted version is dated 1710 and hangs in the Stadel Institute in<br />

Frankfurt. The present Berlin picture was executed in 1718 or 1719 for a private<br />

client. It is a slight variation upon a second version, which Watteau submitted as his<br />

presentation piece to the Royal Academy of Arts in Paris, of which he became a member<br />

in 1717. The Academy version now hangs in the Louvre” (Hagen and Hagen, What<br />

Great Paintings Say 3: 102).<br />

4. “This mythic island, sacred to Venus, not only provides the pilgrims with privacy,<br />

with isolation if not solitude, but also with freedom. The pleasure ground has a deep<br />

association with human feelings and passions; there is a melding of nature and the<br />

human. This grove, this sacred isle of love, summons up a pleasurable association<br />

between painting and observer… The place of love offers comfort not just for those<br />

lovers within it, but for all of us, who are potential lovers, watching. We watch because<br />

we are curious and sometimes covetous” (Minor 33-34). “The change within about eight<br />

years from inhibition to relaxation, from deliberation to excitement, is not due solely to<br />

Watteau‟s greater artistic maturity and happy awareness of his own skill, but also to<br />

the general sense of liberation felt after the death of Louis XIV, when hopes were high<br />

for favorable political developments” (Borsch-Supan 66). “Watteau‟s fragile forms and<br />

delicate colors, painted with feathery brushstrokes reminiscent of Rubens, evoke a<br />

mood of reverie and nostalgia. His doll-like men and women provide sharp contrast<br />

with Rubens‟ physically powerful figures or, for that matter, with Poussin‟s idealized<br />

heroes. Watteau‟s art conveys no noble message; rather, it explores the world of<br />

familiar but transitory pleasures” (Fiero, Faith, Reason, and Power 143).<br />

23

UNIT NINE: Late Baroque and Rococo STUDY GUIDE<br />

G Antoine Watteau. Pierrot, called Gilles, c. 1718, oil on<br />

canvas<br />

(Pierrot) Gilles, an Italian actor/ commedia dell‟Arte/ a<br />

portrait of psychological insight/ an early death of<br />

tuberculosis<br />

1. “The more wistful side of Watteau can be seen in his undated Gilles, the<br />

sad Harlequin. The actor, in this case a comic lover, wears his costume, but<br />

does not perform. His pose is frontal, and his arms hang limply at his<br />

sides. His melancholy expression betrays his mood, and is at odds with the<br />

silk costume and pink ribbons on his shoes. Presently between roles, the<br />

actor is „all dressed up with nowhere to go.‟ The blue-gray sky echoes the<br />

figure‟s mood, as do the sunset-colored clouds. End of day, which is<br />

indicated by the sunset, corresponds to the sense that Gilles is at a loss<br />

about what to do next. His lonely isolation is accentuated by the four<br />

figures around him, who seem engaged in animated conversation” (Adams,<br />

Art Across Time 681).<br />

2. “Many of Watteau‟s paintings center on the commedia dell’arte. His<br />

treatment of this Italian theme is all the more remarkable because the<br />

commedia dell‟arte was officially banned in France from 1697 until 1716”<br />

(Janson 595). This work “was probably done as a sign for a café owned by a<br />

friend of the artist who retired from the stage after achieving fame in the<br />

racy role of the clown. The performance has ended, and the actor has<br />

stepped forward to face the audience. The other characters, all highly<br />

individualized, are probably likenesses of friends from the same circle. Yet<br />

the painting is more than a portrait or an advertisement. Watteau<br />

approaches his subject with incomparable human understanding and<br />

artistic genius. Pierrot is lifesize, so that he confronts us as a full human<br />

being, not simply as a stock character. In the process, Watteau transforms<br />

him into Everyman, with whom he evidently identified himself- a merging of<br />

identity basic to the commedia dell‟arte… Like the rest of the actors, except<br />

the doctor on the donkey who looks mischievously at us, he seems lost in<br />

his own thoughts” (595).<br />

4. “The large scale of the picture is surprising, and the onlooker is drawn to<br />

the curiously static centrally placed figure, dressed in theatrical costume,<br />

his arms and hands hanging symmetrically in front of him. His facial<br />

expression seems to combine both mirth and sadness, perhaps suggesting<br />

the transitory nature of pleasure. Shortly after Watteau made this painting<br />

he died of tuberculosis as did the patron and model of the work” (Bolton 74).<br />

5. “Tragically, Watteau died from tuberculosis<br />

when still in his thirties. During his final<br />

illness, while staying with the art dealer Edme-<br />

Francois Gersaint, he painted a signboard for<br />

Gersaint‟s shop. The dealer later wrote,<br />

implausibly, that Watteau had completed the<br />

painting in about a week, working only in the<br />

mornings because of his failing health” (810).<br />

6. “The curious spatial relationship between the<br />

central figure and the other actors can be<br />

explained by supposing that Gilles is standing<br />

on a raised, narrow stage made to look like a<br />

piece of ground. Behind this platform, the other<br />

actors are coming up behind him with the<br />

donkey, and the background is a painted backcloth, strictly speaking a<br />

picture within a picture. This witty interplay links the painting to Gersaint’s<br />

Shop Sign, while the construction of the stage is reminiscent of that in<br />

French Players” (Borsch-Supan 62). “A comparison with Hyacinthe<br />

Rignaud‟s Louis XIV in Armor of 1701 makes this work… seem almost like a<br />

calculated insult to royalty. The comedy of the role of Pierrot turns to<br />

dignity, and the symmetry of the large format engenders a sense of majesty<br />

based on the nature of humanity” (57).<br />

24<br />

H Francois Boucher. Cupid a Captive,<br />

1754, oil on canvas<br />

Francois Boucher/ Rococo sense of sensual<br />

playfulness/ pastel colors/ artificial<br />

treatment of nature/ Madame de<br />

Pompadour<br />

1. “The artist most closely<br />

associated today with<br />

Parisian Rococo painting is<br />

Francois Boucher (1703-<br />

1770), who never met<br />

Watteau. In 1721,<br />

Boucher, the son of a minor<br />

painter, entered the<br />

workshop of an engraver to<br />

support himself as he<br />

attempted to win favor at<br />

the Academy. The young<br />

man‟s skill drew the<br />

attention of a devotee of<br />

Watteau, who hired<br />

Boucher to reproduce<br />

Watteau‟s paintings in his<br />

collection, an event that<br />

firmly established the<br />

direction of Boucher‟s<br />

career” (Stokstad, Art<br />

History 812).<br />

2. “After studying at the French Academy in Rome from<br />

1727 to 1731, Boucher settled in Paris and became an<br />

academician. Soon his life and career were intimately<br />

bound up with two women: The first was his artistically<br />

talented wife, Marie-Jeanne Buseau, who was a<br />

frequent model as well as a studio assistant to her<br />

husband. The other was Louis XV‟s mistress, Madame<br />

de Pompadour, who became his major patron and<br />

supporter. Pompadour was an amateur artist herself<br />

and took lessons from Boucher in printmaking. After<br />

Boucher received his first royal commission in 1735, he<br />

worked almost continuously to decorate the royal<br />

residences at Versailles and Fontainebleau. In 1755,<br />

he was made chief inspector at the Gobelins Tapestry<br />

Manufactory, and he provided designs to it and to the<br />

Sevres porcelain and Beauvais tapestry manufactories,<br />

all of which produced furnishings for the king” (812).<br />

3. “As a promoter of moral painting, the French critic<br />

Denis Diderot despised Boucher. In his Salon reviews<br />

of 1765 he wrote: „I don‟t know what to say about this<br />

man. Degradation of taste, color, composition,<br />

character, expression, and drawing have kept pace with<br />

moral depravity‟” (Minor 195). “Many critics have<br />

dismissed or denounced Boucher for his „frivolous‟<br />

subject matter… but it takes a narrow and puritanical<br />

nature to miss the importance of these paintings” (195).<br />

“Boucher‟s brushwork is as abandoned as the mood of<br />

his paintings. Not that he was messy or thoughtless in<br />

his technique; he simply understood that painting can<br />

bewitch the spectator with its sheer audacity, its<br />

exuberant love of the act of fashioning paints into<br />

luxurious forms” (195). “Neither the King nor his<br />

mistress were lazy, but they understood the erotic and<br />

pleasurable charge of indolence” (195).

UNIT NINE: Late Baroque and Rococo STUDY GUIDE<br />

I Jean-Honore Fragonard. The Swing, 1766, oil on canvas<br />

Jean-Honore Fragonard/ an “intrigue” picture for Baron St. Julien/<br />

three graces and Cupid‟s warning/ Rococo touches of sensuality and<br />

playfulness/ artificial lighting<br />

1. “When the mother of young Jean-Honore Fragonard (1732-<br />

1806) brought her son to Boucher‟s studio around 1747-1748,<br />

the busy court artist recommended that the boy first study the<br />

basics of painting with his contemporary and friend, Jean-<br />

Simeon Chardin. Within a few months, Fragonard returned<br />

with some small paintings done on his own, and Boucher<br />

gladly welcomed him as an apprentice-assistant at no charge<br />

to his family. Boucher encouraged the boy to enter the<br />

competition for the Prix de Rome, which Fragonard won in<br />

1752. Fragonard returned to Paris in 1761, but not until<br />

1765 was he finally accepted into the Royal Academy.<br />

Fragonard began catering to the tastes of an aristocratic<br />

clientele, and by 1770 he began to fill the vacuum left by<br />

Boucher‟s death as a decorator of interiors” (Stokstad, Art<br />

History 812-3).<br />

2. “When he was 35 years old, he decided to work as an independent artist producing<br />

work for the art dealers and rich collectors of the ancien regime, who wanted intimate<br />

work for their salons and boudoirs. He had enormous artistic and financial success,<br />

painting delightful airy scenes of gallantry and frivolity that embody the spirit of the<br />

Rococo. However, the Revolution of 1789 and the new taste for Neoclassicism changed<br />

the world in which he had flourished. He died impoverished, unnoticed, and out of<br />

fashion” (Cumming, Great Artists 58).This painting “was commissioned by the libertine<br />

Baron de St. Julien. He initially gave the order to a painter of historical subjects, Doyen.<br />

Spelling out his requirements, the Baron said, „I should like you to paint Madame [his<br />

mistress] seated on a swing being pushed by a bishop.‟ Shocked by the request, Doyen<br />

refused the commission… Fragonard accepted the work enthusiastically, but replaced the<br />

bishop with the girl‟s husband” (58-9).<br />

3. “The stone statue of Cupid catches the sunlight and seems to have come alive. He<br />

raises a finger to his lips as if warning us to keep the secret of the Baron hidden in the<br />

bushes… Around the base of the statue of Cupid the Three Graces appear as a classical<br />

relief. In Greek mythology, the Graces were attendants of Venus, the goddess of love.<br />

Fragonard half-hides them, as if to emphasize his lack of interest in the art of classical<br />

antiquity” (59). “Fragonard mastered the pleasing effect of dappled sunlight, which<br />

illuminates many of his works… The slipper flying through the air is a brilliant touch,<br />

which adds a focus of visual attention and sums up the playfulness of the subject… The<br />

fantastic trees owe more to the artist‟s memories of his childhood and his student days<br />

that they do to observation from nature. Fragonard was raised in the lush, flower-filled<br />

region of Grasse- the center of the perfume industry. As a student in Italy, he was more<br />

excited by the luxurious pleasure gardens at Tivoli, where he spent the summer of 1760,<br />

than he was by antique sculpture” (58-9).<br />

4. “There is another place of pleasure, the locus uberimus, from the Latin word for the<br />

rich and fertile. The Swing by Jean-Honore Fragonard presents us with a typical instance.<br />

An oddly radiant light wells up within the left-hand corner and enchants this overly<br />

luxuriant glade. Nature explodes with leaves and flowers. As if the force of nature were<br />

somewhat demented, trees erupt violently from the ground and twist tortuously.<br />

Certainly, not everything is charmed here; there is more than a hint of perversity… The<br />

statues, the rhythmically rocking young woman, a voyeur, and a yammering lap dog<br />

create a disturbing, fertile excitement and sensibility” (Minor 35, 37). “The subject of this<br />

painting was suggested by the Baron de St. Julien, who commissioned it and who is<br />

depicted in it as the rakish voyeur. Fragonard skillfully frames the scene in foliage and<br />

uses all sorts of detail to add tension: the slipper which has flown off, the slightly frayed<br />

and slightly twisted ropes, and the tortuously curving branches” (37). “Whether or not the<br />

young lady is aware of her lover‟s presence, her coy gesture and the irreverent behavior of<br />

the ménage a trios (lover, mistress, and cleric) create a mood of erotic intrigue similar to<br />

that found in the comic operas of this period, as well as in the pornographic novel, which<br />

developed as a genre in eighteenth-century France… Although Fragonard immortalized<br />

the union of wealth, privilege, and pleasure enjoyed by the upper classes of the eighteenth<br />

century, he captured a spirit of sensuous abandon that has easily outlived the particulars<br />

of time, place, and social class” (Fiero, Faith, Reason, and Power 145-146).<br />

25<br />

J Voltaire and the Pursuit of<br />

Happiness<br />

1. “The pursuit of happiness and the<br />

belief in its attainment permeate the<br />

paintings of the French artist Jean-<br />

Honore Fragonard (1732-1806). In The<br />

Swing (1766) Fragonard depicts, with<br />

delicious wit, a lovers‟ assignation. This<br />

optimism was assailed by the leading<br />

French intellectual of the<br />

Englightenment, Francois-Marie Arouet<br />

(1694-1778), who preferred to be called<br />

Voltaire. Known for his penetrating wit<br />

and brilliant style, Voltaire survived a<br />

turbulent career that resulted in two<br />

periods of incarceration in the Bastille<br />

and in three years of exile in England”<br />

(Wren 2: 193-4).<br />

2. “A champion of the principle of reason,<br />

Voltaire reacted sharply against the<br />

optimistic philosophical theories of<br />

Liebniz. In his satirical novel Candide<br />

(1759), Voltaire seized upon Leibniz‟s<br />

axiom that this was the best of all<br />

possible worlds. Candide, the central<br />

character of the novel, is a youthful<br />

disciple of Doctor Pangloss, who is a<br />

disciple of Leibniz. Candide and a<br />

beautiful young woman, Cunegund, fall<br />

in love, but are separated by her parents,<br />

who consider Candide too lowly in birth<br />

to court their highborn daughter.<br />

Stumbling through a world of ignorance,<br />

cruelty, and violence, Candide,<br />

Cunegund, and Pangloss each endure<br />

beatings, torture, rape, imprisonment,<br />

slavery, disease, and disfigurement. At<br />

the end of their misadventures, the<br />

much-sobered trio retires to the shores of<br />

the Pronpontis, there to discover that the<br />

secret to happiness was „to cultivate one‟s<br />

garden‟” (194). Voltaire “hated… the<br />

arbitrary despotic rule of kings, the<br />

selfish privileges of the nobility and the<br />

church, religious intolerance, and above<br />

all, the injustice of the ancien regime (the<br />

„old order‟)… Voltaire believed that the<br />

human race could never be happy until<br />

the traditional obstructions to the<br />

progress of the human mind and welfare<br />

were removed… This conviction paved the<br />

way for a revolution in France that<br />

Voltaire never intended, and he probably<br />

never would have approved of it. He was<br />

not convinced that „all men are created<br />

equal,‟ the credo of Jean-Jacques<br />

Rousseau, Thomas Jefferson, and the<br />

American Declaration of Independence”<br />

(Kleiner, Mamiya, and Tansey 837).<br />

“More than any of the philosophes,<br />

Voltaire extolled the traditions of non-<br />

Western cultures, faiths, and moralities”<br />

(Fiero, Faith, Power, and Reason 121).

UNIT NINE: Late Baroque and Rococo STUDY GUIDE<br />

K Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun. Marie Antoinette and her Children, 1787, oil on canvas<br />

Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun/ Marie Antoinette/ emphasis on / motherhood/ Rococo love of sentiment<br />

1. Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun (1755-1842) “painted several portraits of Marie Antoinette, the Austrian-born<br />

queen of Louis XVI… Vigée-Lebrun befriended monarchs and their families, and benefited from their<br />

patronage. Her 1788 portrait of Marie Antoinette and her Children depicts the Queen of France in an elegant,<br />

regal setting, oblivious to the social, political, and economic unrest among her subjects that would erupt the<br />

following year and culminate in the French Revolution. The variety of rich textures- silks, laces, and brocades,<br />

and Marie Antoinette‟s enormous feathered hat- emphasize the wealth and position of the sitters. At the same<br />

time, the Queen shows her ease with motherhood. One daughter nestles against her shoulder and the toddler<br />

squirms on her lap. The boy introduces a somber note as he pulls aside the crib cover to reveal the empty<br />

bed, denoting the death of one of Marie Antoinette‟s children” (Adams, Art Across Time 684). “In 1783, Vigée-<br />

Lebrun was elected to one of the four places in the French Academy available to women. As the favorite<br />

painter to the queen, Vigée-Lebrun escaped from Paris with her daughter on the eve of the Revolution of 1789<br />

and fled to Rome. After a very successful self-exile working in Italy, Austria, Russia, and England, the artist<br />

finally resettled in Paris in 1804 at the invitation of Napoleon I and again became popular with Parisian art<br />

patrons. Over her long career, she painted around 800 portraits in a vibrant style that changed very little over<br />

the decades” (Stokstad, Art History 935).<br />

2. “Her portrait of Marie-Antoinette en chemise raised a few eyebrows at the Salon in 1783; indeed, under pressure she withdrew the<br />

painting from the exhibition. Because this expensive, casual clothing- known as a chemise en robe- was associated by many with lingerie,<br />

the artist was perceived as having broken rules of decorum. But we know that the Queen loved this relaxed, even intimate, portrait of<br />

herself. With the cult of sensibility has done, perhaps without either the Queen or her artist being very conscious of the fact, was to<br />

undermine, or compromise, the power of the monarchical portrait” (Minor 232). “Vigee-Lebrun did not cast her subjects as goddesses, but<br />

she imparted to them a chic sweetness and artless simplicity. These talents earned her the equivalent of over $200,000 a year and<br />

allowed her an independence uncommon among eighteenth-century women” (Fiero, Faith, Reason, and Power 145).<br />

L Jean-Simeon Chardin. Grace at Table, 1740, oil on canvas<br />

Jean-Simeon Chardin/ environment free of corrupt society/ discarded toys vs. properly set table/ art of<br />

instruction and moral uplift in a middle class home<br />

1. “The son of a furniture maker, Jean-Baptiste-Simeon Chardin (1699-1779) probably originally intended to<br />

work in his father‟s trade. In 1718, however, he was apprenticed to a painter, and being quite gifted, soon<br />

acquired the basics of this craft. At age twenty-eight he presented two paintings to the Royal Academy hoping<br />

to gain admission. The academicians were so dazzled by these works- especially The Ray Fish, which<br />

represents an enormous, glistening, disemboweled ray fish suspended from a hook and a cat tiptoeing toward<br />

the foreground over open oysters- that Chardin was immediately accepted as a full member” (Govignon 195).<br />

“Chardin specialized first in small still lifes of kitchen utensils and food laid out for the cook. Around 1733 he<br />

began to paint genre subjects- scenes from everyday life- starting with the charming Lady Sealing a Letter,<br />

hoping to widen his repertory and win new clients. Thereafter he produced many such scenes showing, for<br />

example, maids doing the laundry or a governess helping children dress for school. His paintings of children<br />

are especially poetic, showing them as rather grave young adults, completely absorbed in their games” (195).<br />

2. “A gentle sentiment prevails in all of his pictures, an emotion not contrived and artificial but born of the<br />

painter‟s honesty, insight, and sympathy. (It is interesting that this picture was owned by King Louis XV, the<br />

royal personification of the Rococo in his life and tastes.)” (Kleiner, Mamiya, and Tansey 842). “Everyone knows the story-or legend?- of<br />

how he was prodded into painting human forms. One day he heard his friend Aved refuse a commission of four hundred livres to paint a<br />

portrait; Chardin, accustomed to small fees, marveled at the refusal; Avel answered, „You think a portrait is as easy to paint as a<br />

sausage?‟ It was a cruel jibe, but useful; Chardin had confined his subjects too narrowly, and would soon have satiated his clients with<br />

dishes and food. He resolved to paint figures, and discovered in himself a genius of sympathetic portrayal that he had allowed to sleep”<br />

(Durant, Age of Voltaire 318).<br />

3. “In Saying Grace (at the Salon it was called Bénédicité, which is the first word of Grace, from the Latin benedicite), a mother pauses in<br />

the process of ladling out the meal of her two young children, as the smaller of these falters over the simple prayer, glancing up to her for<br />

assistance. His sister looks on, not without malice, at his difficulty. The legend on Lepicie‟s engraving of 1744 suggests that the little boy<br />

is garbling his prayer as fast as possible, because his mind is more on his food. Again the setting is a simple bourgeois, living-room,<br />

comfortable with its damask tablecloth and a pair of good upholstered chairs; the brazier at the right „answers‟ the pug and work-box in<br />

the companion picture” The Industrious Mother (Conisbee 162-163). “Although he was unsurpassed as a still-life painter, he always<br />

regretted that his father lacked the means to provide him with a humanistic education and therefore prepare him for history painting, the<br />

most prestigious of all forms of art in the Baroque and Rococo periods” (Minor 252). “The values of simplicity, truth, and naturalness were<br />

much promoted in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries as an antidote to the corruption of the court and the city. The disasters of<br />

the final years of Louis XIV‟s reign, followed shortly by a catastrophic stock market crash in Paris in 1720, encouraged many to seek<br />

modest values and personal virtue. The work ethic promoted by the middle class went hand in hand with a strong attachment to family<br />

and the pursuit of prosperity” (262-263).<br />

26

UNIT NINE: Late Baroque and Rococo STUDY GUIDE<br />

M Jean Simeon Chardin. The Copper Water Urn,<br />

c. 1734, oil on panel<br />

still life of solemn domesticity<br />

1. “These now universally acclaimed<br />

pictures found a very limited market<br />

and brought Chardin just enough<br />

francs to maintain him in contented<br />

simplicity. He could not haggle with<br />

customers; he let his pictures go for<br />

almost any offered fee; and as he<br />

worked slowly and laboriously, he wore<br />

himself out in relative poverty, while<br />

Boucher used himself up in affluence.<br />

When his first wife died, after only four<br />

years of marriage, he let his rooms and<br />

affairs fall into a baccalaureate<br />

disorder. His friends prevailed upon<br />

him to remarry, if<br />

only to have a woman‟s deft and patient hand restore some order<br />

to his ménage. He hesitated for nine years, then took to wife the<br />

widow Marguerite Pouget, in literally a marriage of convenience.<br />

She brought him a moderate dowry, including a house that she<br />

owned at 13 Rue Princesse. He moved into it, and his poverty<br />

ended. She was a good woman and a solicitous wife. He learned<br />

to love her gratefully” (Durant, Age of Voltaire 318-9).<br />

2. “To further finance him the King gave him (1752) a pension of<br />

five hundred livres, and the Academy (1754) appointed him<br />

treasurer. Soon afterward it engaged him to place the pictures<br />

submitted to its Salons; he was thoroughly un-suited to this task,<br />

but his wife helped him. In 1756 a friendly engraver, Charles<br />

Nicolas Cochin II, persuaded Marigny to give Chardin a<br />

comfortable apartment in the Louvre” (319). “Chardin tended to<br />

work on a small scale, meticulously and slowly. His still lifes<br />

consisted of a few simple objects that were to be enjoyed for their<br />

subtle differences of shape and texture, not for any virtuoso<br />

performance, complexity of composition, or moralizing content”<br />

(Stokstad, Art History 932-3).<br />

3. “For all that Chardin‟s signature is like a graffito on the wall,<br />

this is not illusionistic painting; the brown thong on the handle of<br />

the pan is suggested, not defined, an angular and twisting gesture<br />

of the paint-loaded brush. Placed firmly as these solidly painted<br />

objects are on the floor at the end of their kitchen, they take on a<br />

presence even more immediate that the utensils we have seen<br />

artfully arranged at eye level on their stone ledges. Somehow the<br />

spectator can identify with this space, could walk in on this small<br />

area of floor. It seems to require but one step for a maidservant to<br />

enter Chardin‟s pictorial world, and to confirm the already vivid<br />

existence of these vessels with use” (Conisbee 105).<br />

4. Chardin “arranged his shadows carefully and had a strong<br />

discernment and awareness of tactile values- of the apparent<br />

touchability of the objects that he painted. There is nothing<br />

unusually beautiful about the specimens that he selects, but there<br />

is a strong sense of substance and geometry, as if he were aware<br />

that lying beneath these humble forms were the principles of the<br />

cone, the cylinder, and the sphere- the basic geometries of nature.<br />

Just the same, for all their careful structure, Chardin‟s still lifes<br />

appear unstudied and natural” (Minor 253). “His technique was to<br />

prime his canvases with a priming, which was then covered by<br />

some dense paint, such as a mixture of white lead with reddish<br />

brown… Thus he painted from dark to light, adding the lightest<br />

part toward the end. His final pass over the painting would be with<br />

a varnish that would „pull it together‟ ” (253).<br />

27<br />

N Denis Diderot<br />

1. “Chardin‟s work was praised by Denis Diderot, a leading<br />

Enlightenment figure whom many consider the father of modern<br />

art criticism. Diderot‟s most notable contribution was editing<br />

the Encyclopedie (1751-1765), a seventeen-volume<br />

compendium of knowledge and opinion to which many of the<br />

major Enlightenment thinkers contributed. In 1759, Diderot<br />

began to write reviews of the official Salon for a periodic<br />

newsletter for wealthy subscribers. Diderot believed that it was<br />

art‟s proper function to „inspire virtue and purify manners.‟ He<br />

therefore praised artists such as Chardin and criticized the<br />

adherents of the Rococo” (Stokstad 933).<br />

2. “Diderot‟s highest praise went to Jean-Baptiste Greuze<br />

(1725-1805)- which is hardly surprising, because Grueze‟s major<br />

source of inspiration came from the kind of drame bourgeois<br />

(„middle-class drama‟) that Diderot had inaugurated in France in<br />

1757. In addition to comedy and tragedy, Diderot felt there<br />

should be a „middle tragedy‟ that taught useful lessons to the<br />

public with clear, simple stories of ordinary life” (933).<br />

O Jean-Jacques Rousseau<br />

1. “The primacy of reason was challenged by the French<br />

philosopher and author Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778).<br />

Rousseau‟s thought ran counter to that of Voltaire and other<br />

Enlightenment thinks. To these thinkers, recent advances in<br />

science and technology were regarded as proof of the superiority<br />

of the rational intellect over instinct and emotion, while future<br />

advances in science and technology were expected to provide the<br />

basis for material progress. Material progress, in turn, was<br />

viewed by most Enlightenment thinkers as the means by which<br />

morality and happiness could be increased among individuals”<br />

(Wren 2: 197-8).<br />

2. “Rousseau, in contrast, was skeptical about material<br />

progress, which he regarded as destructive of an individual‟s<br />

moral well-being and happiness. Rousseau, though never<br />

doubting the attainments of the human intellect, regarded<br />

science and technology as the products of complex civilizations.<br />

In Rousseau‟s view, complex civilizations corrupted, rather than<br />

improved, individuals, by introducing luxury, avarice, sloth, and<br />

decadence. Individuals, according to Rousseau, became the<br />

victims rather than the masters of machines; they became part<br />

of communities that promoted war to further their accumulation<br />

of wealth and their acquisition of territory; and they surrendered<br />

their independence to leaders who developed elaborate systems<br />

of government and law. Rousseau was convinced that, with the<br />

advent of complex civilizations, individuals had ceased to<br />

cherish their original sentiments of liberty and equality and had<br />

become alienated from their natural instincts of kindness,<br />

charity, and pity” (198).<br />

3. “Rousseau expounded many of his major ideas in his<br />

Discourse on the Origin and Foundations of Inequality Among Men<br />

(1754). In this work, Rousseau defines the natural state of the<br />

individual prior to the establishment of political societies.<br />

Rousseau argues that people living according to purely natural<br />

impulses are motivated by the principle of self-preservation,<br />

moderated by natural pity or compassion, and are incapable of<br />

pride, hatred, falsehood, and vice. He further argues that<br />

society, because of its creation of inequalities in property,<br />

wealth, and education, has corrupted the natural good” (198).

UNIT NINE: Late Baroque and Rococo STUDY GUIDE<br />

P On Educating Children<br />

1. “Although he never married and he<br />

placed his own children in orphanages,<br />

the French-Swiss philosopher Jean-<br />

Jacques Rousseau formulated a<br />

behavioral program of childhood<br />

education that affected all French schools<br />

after the Revolution of 1789” (Stokstad,<br />

Art History 935).<br />

2. “Believing that children were inherently<br />

good until society corrupted them and<br />

broke their naturally independent,<br />

inquisitive spirits, Rousseau advised<br />

mothers to breast-feed their babies<br />

themselves, dress them in loose clothing<br />

with no bonnet, wash them in unheated<br />

water, give them freedom to crawl about,<br />

and never rock them, which Rousseau<br />

considered harmful. As boys grew, they<br />

were to be taught to value nature, human<br />

liberty, and personal valor and virtue.<br />

This environment would inevitably<br />

produce a citizen committed to political<br />

freedom and civic duty. Girls were to be<br />

educated only as needed for their futures<br />

as wives and mothers. Once married,<br />

women were to stay at home, out of the<br />

public eye, caring for their households<br />

and children, which Rousseau saw as „the<br />

manner of living that nature and reason<br />

prescribe for the sex‟” (935).<br />

R The French Salon<br />

1. “In the eighteenth century, the<br />

salon became the center of Parisian<br />

society and taste. The typical salon<br />

was the creation of a charming,<br />

financially comfortable, welleducated,<br />

and witty hostess (the<br />

salonniere) in her forties. She<br />

provided good food, a well-set table, and<br />

music for people of achievement in<br />

different fields who visited her hotel. The<br />

guests engaged in the arts of<br />

conversation, and in social and<br />

intellectual interchange” (Adams, Art<br />

Across Time 675).<br />

2. “In the seventeenth century, the most<br />

important salon had been that of<br />

Madame de Rambouillet, who wished to<br />

exert a „civilizing‟ influence on society. By<br />

the next century, the salon was a fact of<br />

Paris social life, and one in which women<br />

played the dominant role. Among the<br />

salonnieres were women of significant<br />

accomplishments in addition to<br />

hostessing. These included writers<br />

(Madames de LaFayette, de Sevigne, and<br />

de Stael, and Mademoiselle de Scudery), a<br />

scientist (Madame de Chatelet), and the<br />

painter Elisabeth Vigee-Lebrun” (675).<br />

Q William Hogarth. Breakfast Party, from the Marriage a la Mode<br />

series, c. 1745, oil on canvas<br />

William Hogarth/ satire of arranged marriages/ suggestion of erotic<br />

activities/ steward with unpaid bills/ part of a series of moralizing<br />

narratives<br />

1. “A different expression of English Rococo is found in the witty, biting commentary of<br />

William Hogarth (1697-1764). Influenced in part by Flemish and Dutch genre paintings,<br />

he took contemporary manners and social conventions as the subjects of his satire. His<br />

series of six paintings entitled Marriage a la Mode from the 1740s pokes fun at<br />

hypocritical commitments to the marriage contract” (Adams, Art Across Time 686). “The<br />

architecture reflects the Neoclassical Palladian style of eighteenth-century England, but<br />

Rococo details fill the interior. The costume frills, for example, echo the French version of<br />

the style. The elaborate chandelier and the wall designs are characteristic of Rococo<br />

fussiness. On the mantelpiece, the bric-a-brac of chinoiserie reflects the eighteenthcentury<br />

interest in Far Eastern exotic objects, as well as referring to a frivolous lifestyle.<br />

They are contrasted with the august pictures of saints in the next room.” (687). “Cupid,<br />

on the other hand, is depicted blowing the bagpipes, which, as in Bruegel‟s Peasant<br />

Dance, signify lust. The dangers of sexual excess, which Hogarth satirizes, are<br />

underscored by locating Cupid among ruins, foreshadowing the inevitable ruin of the<br />

marriage” (687). “Hogarth‟s father was a teacher, from whom his son learned Latin and<br />

Greek. He also opened a Latin-speaking coffee house that went bankrupt. As a result, he<br />

spent three years in debtors‟ prison, until Parliament passed an Act freeing all debtors.<br />

This experience contributed to the artist‟s fierce opposition to social injustice and<br />

hypocrisy. In 1752, Hogarth published his view on art in Analysis of Beauty, which, like<br />

the etching, states his anti-Academic position… He urges people to look at nature and to<br />

themselves, rather than to the plaster casts of traditional art schools, for „what we feel‟”<br />

(687).<br />

2. “In 1751 Hogarth announced that he would sell at auction, at a given hour in his<br />

studio, the oil paintings that he had made for Marriage a la Mode; but he warned picture<br />

dealers to stay away. Only one person appeared, who bid £126 for the pictures and their<br />

frames. Hogarth let them go at this price, but privately raged at what he rated a shameful<br />

failure. In 1797 these paintings bought £1,381; today they are among the most highly<br />

prized possessions of London‟s National Gallery” (Durant, Age of Voltaire 221). “Like most<br />

moralists he was not himself immaculate; he had borne without horror the company of<br />

drunkards and prostitutes…The art critics, collectors, and dealers of the time<br />

acknowledged neither Hogarth‟s ability as an artist nor his truth as a satirist. They<br />

charged him with picturing only the dregs of English life. They taunted him with having<br />

turned to popular prints through inability to paint successful portraits or historical<br />

scenes; and they condemned his drawing as careless and inaccurate” (219, 222).<br />

3. “Hogarth‟s favorite device was to make a<br />

series of narrative paintings and prints, in a<br />

sequence like chapters in a book or scenes<br />

in a play, that followed a character or group<br />

of characters in their encounters with some<br />

social evil” (Kleiner, Mamiya, and Tansey<br />

843). In his Breakfast Scene, “the moment<br />

portrayed is just past noon; husband and<br />

wife are tired after a long night spent in<br />

separate pursuits. The music and the<br />

musical instrument on the overturned chair<br />

in the foreground and the disheveled<br />

servant straightening the chairs and tables<br />

in the room at the back indicate that the<br />

wife had stayed at home for an evening of cards and music making. She stretches with a<br />

mixture of sleepiness and coquettishness, casting a glance toward her young husband,<br />

who clearly had been away from the house for a night of suspicious business. Still<br />

dressed in hat and social finery, he slumps in discouraged boredom on a chair near the<br />

fire. His hands are thrust deep into the empty money-pockets of his breeches, while his<br />

wife‟s small dog sniffs inquiringly at a lacy woman‟s cap protruding from his coat pocket.<br />

A steward, his hand full of unpaid bills, raises his eye to Heaven in despair” (843).<br />

“Paintings of religious figures hang on the upper wall of the distant room. This<br />

demonstration of piety is countered by the curtained canvas at the end of the row that,<br />

undoubtedly, depicts an erotic subject” (843).<br />

28

UNIT NINE: Late Baroque and Rococo STUDY GUIDE<br />

S Thomas Gainsborough. Mr. And Mrs. Andrews, c. 1748-50, oil on canvas<br />

Thomas Gainsborough/ Mr. Andrews as a country gentleman with a love of hunting/ Mrs. Andrews as a<br />

decorative feature/ ripe ears of corn/ little tree between two larger tress/ an enclosure in the distance/<br />

asymmetrical composition<br />

1. “Portraiture remained the only constant source of income for English painters. Here, too<br />

eighteenth-century England produced a style that differed from Continental traditions.<br />

Hogarth was a pioneer in this field as well. The greatest master, however, was Thomas<br />

Gainsborough (1727-1788), who began by painting landscapes but ended as the favorite<br />

portraitist of British high society. His early paintings, such as Robert Andrews and his Wife,<br />

have a lyrical charm that is not always found in his later pictures… The landscape is<br />

derived from Ruisdael and his school but has a sunlit, hospitable air never achieved (or<br />

desired) by the Dutch masters. The casual grace of the two figures, which affect an air of<br />

naturalness, indirectly recalls Watteau‟s style. The newlywed couple- she dressed in the<br />

fashionable attire of the day, he armed with a rifle to denote his status as a country squire<br />

(hunting was a privilege of wealthy landowners) – do not till the soil themselves. The<br />

painting nevertheless conveys the gentry‟s closeness to the land, from which the English<br />

derived much of their sense of national identity” (Janson 600). “An entry in the parish register of the small Suffolk town of Sudbury<br />

records that Robert Andrews married Frances Mary Carter there on 10 November 1748. He was 22 years of age, his bride 16. Also newly<br />

wedded, albeit one year younger than the bridegroom he was to paint, was Thomas Gainsborough himself. In a London chapel notorious<br />

for its secret weddings, he had taken the pregnant Margaret Burr to be his lawful wedded wife” (Hagen and Hagen, What Great Paintings<br />

Say 1:111).<br />

2. “Ripe ears of corn are a fitting fertility symbol for a wedding portrait. Gainsborough‟s realistic landscape also holds a number of other<br />

symbolic references to the couple‟s consummate marriage and hope of issue: a little tree grows between two larger one on the right; the<br />

man‟s casually lowered shotgun and the bird lying in his wife‟s lap may also be seen as discreet erotic allusions” (111). “Feelings had little<br />

sway in the matter of marriage between two wealthy families. The bride was often promised at a very tender age and, like Frances Mary<br />

Carter, married off at the age of 15 or 16. She was little more than a pawn in a business deal… Frances Carter was undoubtedly an<br />

excellent match. The estate of Auberies, upon which Gainsborough has painted the couple, was probably part of her dowry” (114). “The<br />

view from the garden bench gives the appearance of a boundless idyll- not unlike the ideal parkland proposed by the most famous, 18 th<br />

century landscape gardeners. It even includes an occasional cluster of trees: aesthetically indispensable for the interruption of vistas that<br />

would otherwise seem too wide, or too symmetrical. However, functionality in all its forms was considered inappropriate in one of the new<br />

English parks. Cornfields and herds of sheep, not to mention the byre just visible in the background on the left, would be quite out of<br />

place. Gainsborough, it must be concluded, has not painted Mr. And Mrs. Andrews in a park, but on a farm” (115).<br />

3. “In the middle distance a flock of sheep is shown in a neatly enclosed field, and the cattle are separately enclosed a field with a wooden<br />

shelter on the far left of the painting. This is further evidence of the Andrew‟s modern approach to farming. Enclosure farming was an<br />

innovation of the 18 th century that led to more intensive cultivation. Previously, sheep and other livestock were allowed to wander freely<br />

over the same common land, a system that proved to be detrimental to the health of the livestock as well as damaging to crops”<br />

(Cumming, Annotated Art 67). Gainsborough “began his career imitating Jacob van Ruisdael” (Minor 282). He “had made many copies of<br />

landscapes by Rusidael and even had repaired works by the Dutch master” (282).<br />

4. In this work, “the young couple are depicted at their Suffolk estate of Auberies, near Sudbury, at the point where the parkland meets<br />

the cultivated land; the church of All Saints where they were married is in the background. The way in which the figures are set in front<br />

of the landscape derives from Watteau; in later works Gainsborough would integrate his sitters more closely into their landscape settings”<br />

(284). “Gainsborough‟s image of Robert Andrews and his wife depicts the modern landholder as one whose tenancy is beneficial. The<br />

bright, organized landscape to the right attests to the Andrews‟ diligence as proprietors whose concern is in the best interest of cultivation<br />

and conservation. This somewhat provincial couple- much too well dressed actually to work on the farm- are shown in all their selfsatisfaction<br />

against the darkening clouds of an English autumnal afternoon” (284). “We must not imagine that they sat together under a<br />

tree while Gainsborough set up his easel among the sheaves of corn; their costumes were most likely painted from dressed-up artist‟s<br />

mannequins, which may account for their doll-like appearance, and the landscape would have been studied separately” (Langmuir 284).<br />

5. “This kind of picture, commissioned by people „who lived in rooms which were neat but not spacious‟, in Ellis Waterhouse‟s happy<br />

phrase about Gainsborough‟s contemporary Arthur Devis, was a specialty of painters who were not „out of the top drawer‟. The sitters, or<br />

their mannequin stand-ins, are posed in „genteel attitudes‟ derived from manuals of manners. The nonchalant Mr. Andrews, fortunate<br />

possessor of a game license, has his gun under his arm; Mrs. Andrews, ramrod straight and neatly composed, may have been meant to<br />

hold a book, or, it has been suggested, a bird which her husband has shot. In the event, a reserved space left in her lap has not been<br />

filled in with any identifiable object” (284). “Out of these conventional ingredients Gainsborough has composed the most tartly lyrical<br />

picture in the history of art. Mr. Andrew‟s satisfaction in his well-kept farmlands is as nothing to the intensity of the painter‟s feeling for<br />

the gold and green of fields and copses, the supple curves of fertile land meeting the stately clouds. The figures stand out brittle against<br />

that glorious yet ordered bounty. But how marvelously the acid blue hoped skirt is deployed, almost, but not quite, rhyming with the<br />

curved bench back, the pointy silk shoes in sly communion with the bench feet, while Mr. Andrews‟s substantial shoes converse with tree<br />

roots. (The faithful gun dog had better watch out for his unshod paws.) More rhymes and assonances link the lines of guns, thighs, dog,<br />

calf, coat; a coat tail answers the hanging ribbon of a sunhat; something jaunty in the husband‟s tricorn catches the corner of his wife‟s<br />

eye. Deep affection and naïve artifice combine to create the earliest successful depiction of a truly English idyll” (284-285).<br />

29

UNIT NINE: Late Baroque and Rococo STUDY GUIDE<br />

T Thomas Gainsborough. Mrs. Richard Brinsley Sheridan, 1787, oil on canvas<br />

an elegant portrait inspired by van Dyck/ a pastoral, “natural” setting/ David Hume‟s “natural man”<br />

1. “A number of British patrons… remained committed to the kind of portraiture Van Dyck had brought to<br />

England in the 1620s, which had featured more informal poses against natural vistas. Thomas Gainsborough<br />

achieved great success with this mode when he moved to Bath in 1759 to cater to the rich and fashionable<br />

people who had recently begun to go there in great numbers. A good example of this mature style is the<br />

Portrait of Mrs. Richard Brinsley Sheridan, which shows the professional singer and wife of a celebrated<br />

playwright seated informally outdoors” (Stokstad, Art History 933-4).<br />

2. With the aid of his light, Rococo palette and feathery brushwork, Gainsborough displays an ability to<br />

integrate his sitter into the landscape. “The effect is especially noticeable in the way her windblown hair<br />

matches the tree foliage overhead. The work thereby manifests one of the new values of the Enlightenment:<br />

the emphasis on nature and the natural as the sources of goodness and beauty” (934).<br />

3. “Elizabeth Linley‟s beauty and exceptional soprano voice brought her professional success in concerts and<br />

festivals in Bath and London. After marrying Sheridan in 1773 she left her career to support and participate<br />

in her husband‟s activities as politician, playwright, and orator. Sheridan‟s work was immensely popular, and<br />

his witty plays, A School for Scandal and The Rivals, are a beloved part of today‟s theatrical repertoire. Mrs.<br />

Sheridan is shown here at the age of thirty-one, a mature and elegant woman. Merged into the landscape, her<br />

gracious form bends to the curve of the trees behind her. Light plays as quickly and freely across her dress as it does across the clouds<br />

and the sky. The distinct textures of rocks, foliage, silk, and hair are unified by the strong, animated rhythms of Gainsborough‟s brush.<br />

The freely painted, impressionistic style of Mrs. Sheridan‟s costume and the windblown landscape reflect the strong romantic component<br />

in Gainsborough‟s artistic temperament. However, his primary focus remains on his sitter‟s face and on her personality. Her chin and<br />

mouth are firm, definite, and sculptural, and her heavily drawn eyebrows give her a steady, composed, and dignified expression. There is<br />

a hint of romantic melancholy in her eyes, with their slightly indirect gaze” (Anderson 152). “Thomas Gainsborough prospered greatly from<br />

the portrait trade, but both he and his patrons preferred a light and airy version of the sentimental portrait, what Joshua Reynolds in not<br />

very complimentary terms called „fancy pictures‟. Because he objected to the great height at which pictures were hung in the Royal<br />

Academy, Gainsborough quarreled with the organizers of the exhibition in 1784 and refused thereafter to participate, preferring to show<br />

his paintings at his own home, where he had control over the lighting and display. He insisted upon a close view: his conception of a<br />

picture was of something delicate and fine, not ponderous and dense” (Minor 235).<br />

U Sir Joshua Reynolds. Mrs. Sarah Siddons as the Tragic Muse, 1784, oil on canvas<br />

Sir Joshua Reynolds/ Discourses on Art/Sarah Siddons/ portrait in the grand style (or “grand manner”<br />

portraiture)<br />

1. “While the burgeoning middle classes in France and England were embracing the work of Greuze and<br />

Hogarth, their upper-class contemporaries continued to commission flattering portraits. The leading portrait<br />

painter in late-eighteenth century England was probably Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792), the inaugural<br />

president of the Royal Academy (established in 1768). His Fifteen Discourses to the Royal Academy (1769-<br />

1790) set out his theories on art: Artists should follow the rules derived from studying the great masters of the<br />

past, especially those who worked in the classical tradition; art should generalize to create the universal rather<br />

than the particular; and the highest kind of art is history painting” (Stokstad, Art History 933). “Because<br />

British patrons preferred portraits of themselves to scenes of classical history, Reynolds attempted to elevate<br />

portraiture to the level of history painting by giving it a historical or mythological veneer” (933). “We now tend<br />

to prefer the fresher brush of his rival Gainsborough to Reynold‟s contrivances. A restless and indiscriminate<br />

experimenter with media and pigments, imitating the surface effects of Old Master paintings without an<br />

understanding of their methods, he saw his pictures fade, flake and crack, so that portraits „died‟ before their<br />

sitters. Even his contemporaries protested at his technical shortcomings. Yet the more we look at Reynolds,<br />

in the prodigious variety which Gainsborough rightly envied, the more we see that he indeed achieved what he<br />

defined as‟ that one great idea, which gives to painting its true dignity… of speaking to the heart.” (Langmuir<br />

316).<br />

2. Unlike Reynolds, “Gainsborough did little reading, had few intellectual interests, shunned the circle of wits that gathered around<br />

[Samuel] Johnson.” (Durant, Rousseau and Revolution 757) “Reynolds was a man; of the world, ready to make the obeisances required for<br />

social acceptance; Gainsborough was a passionate individualists who raged at the sacrifices demanded of his personality and his art as<br />

the price of success” (755). “Reynolds‟ Grand Style did not exclude the sense of play and sentiment typical of the age. Sarah Siddons was<br />

the most famous tragic actress of her time, especially renowned for her portrayal of Lady Macbeth in Shakespeare‟s play Macbeth… Yet<br />

her pose here is nonchalant- it gives an appearance of being effortless or unposed. One of the stories associated with the painting tells us<br />

that Sarah Siddons, late for her sitting, rushed into Reynolds‟ studio, threw herself on the throne, removed her bonnet, rested her head<br />

momentarily in her hand, then turned to the painter and asked, „How shall I sit?‟ „Just as you are,‟ Sir Joshua replied. Mrs. Siddons also<br />

related to another painter that the pose came from an idle moment when Reynolds was preparing some colors and she happened to turn<br />

and look at another of the artist‟s paintings hanging on the wall. He saw the expression and pose, and asked that she hold it” (Minor<br />

233).<br />

30

UNIT NINE: Late Baroque and Rococo STUDY GUIDE<br />

Sir Joshua Reynolds. Mrs. Sarah Siddons as the<br />

Tragic Muse, 1784, oil on canvas (CONTINUED)<br />

3. Gainsborough also “painted Mrs. Siddons in a conscious attempt to<br />

outdo his great rival on the London scene, Sir Joshua Reynolds, who had<br />

portrayed the same sitter as the Tragic Muse. Reynolds, a less adept<br />

painter, had to rely on pose and expression to suggest the aura of<br />

character that Gainsborough was able to convey through color and<br />

brushwork alone. Reynolds, who had been president of the Royal<br />