Preliminary Evidence for White Matter Tract Abnormalities in Young ...

Preliminary Evidence for White Matter Tract Abnormalities in Young ...

Preliminary Evidence for White Matter Tract Abnormalities in Young ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

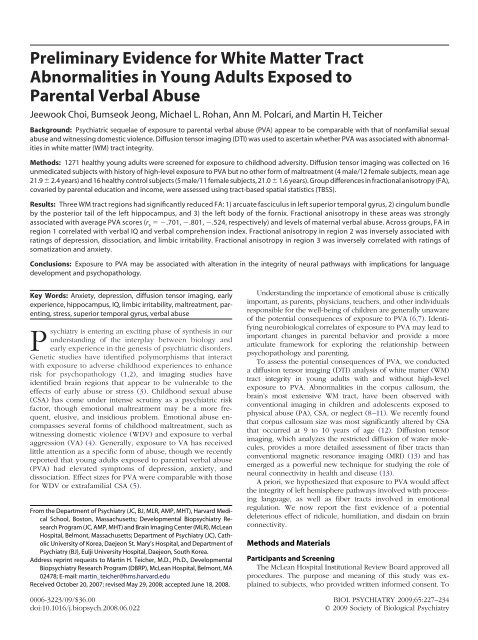

<strong>Prelim<strong>in</strong>ary</strong> <strong>Evidence</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>White</strong> <strong>Matter</strong> <strong>Tract</strong><br />

<strong>Abnormalities</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Young</strong> Adults Exposed to<br />

Parental Verbal Abuse<br />

Jeewook Choi, Bumseok Jeong, Michael L. Rohan, Ann M. Polcari, and Mart<strong>in</strong> H. Teicher<br />

Background: Psychiatric sequelae of exposure to parental verbal abuse (PVA) appear to be comparable with that of nonfamilial sexual<br />

abuse and witness<strong>in</strong>g domestic violence. Diffusion tensor imag<strong>in</strong>g (DTI) was used to ascerta<strong>in</strong> whether PVA was associated with abnormalities<br />

<strong>in</strong> white matter (WM) tract <strong>in</strong>tegrity.<br />

Methods: 1271 healthy young adults were screened <strong>for</strong> exposure to childhood adversity. Diffusion tensor imag<strong>in</strong>g was collected on 16<br />

unmedicated subjects with history of high-level exposure to PVA but no other <strong>for</strong>m of maltreatment (4 male/12 female subjects, mean age<br />

21.9 2.4 years) and 16 healthy control subjects (5 male/11 female subjects, 21.0 1.6 years). Group differences <strong>in</strong> fractional anisotropy (FA),<br />

covaried by parental education and <strong>in</strong>come, were assessed us<strong>in</strong>g tract-based spatial statistics (TBSS).<br />

Results: Three WM tract regions had significantly reduced FA: 1) arcuate fasciculus <strong>in</strong> left superior temporal gyrus, 2) c<strong>in</strong>gulum bundle<br />

by the posterior tail of the left hippocampus, and 3) the left body of the <strong>for</strong>nix. Fractional anisotropy <strong>in</strong> these areas was strongly<br />

associated with average PVA scores (r s .701, .801, .524, respectively) and levels of maternal verbal abuse. Across groups, FA <strong>in</strong><br />

region 1 correlated with verbal IQ and verbal comprehension <strong>in</strong>dex. Fractional anisotropy <strong>in</strong> region 2 was <strong>in</strong>versely associated with<br />

rat<strong>in</strong>gs of depression, dissociation, and limbic irritability. Fractional anisotropy <strong>in</strong> region 3 was <strong>in</strong>versely correlated with rat<strong>in</strong>gs of<br />

somatization and anxiety.<br />

Conclusions: Exposure to PVA may be associated with alteration <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>tegrity of neural pathways with implications <strong>for</strong> language<br />

development and psychopathology.<br />

Key Words: Anxiety, depression, diffusion tensor imag<strong>in</strong>g, early<br />

experience, hippocampus, IQ, limbic irritability, maltreatment, parent<strong>in</strong>g,<br />

stress, superior temporal gyrus, verbal abuse<br />

Psychiatry is enter<strong>in</strong>g an excit<strong>in</strong>g phase of synthesis <strong>in</strong> our<br />

understand<strong>in</strong>g of the <strong>in</strong>terplay between biology and<br />

early experience <strong>in</strong> the genesis of psychiatric disorders.<br />

Genetic studies have identified polymorphisms that <strong>in</strong>teract<br />

with exposure to adverse childhood experiences to enhance<br />

risk <strong>for</strong> psychopathology (1,2), and imag<strong>in</strong>g studies have<br />

identified bra<strong>in</strong> regions that appear to be vulnerable to the<br />

effects of early abuse or stress (3). Childhood sexual abuse<br />

(CSA) has come under <strong>in</strong>tense scrut<strong>in</strong>y as a psychiatric risk<br />

factor, though emotional maltreatment may be a more frequent,<br />

elusive, and <strong>in</strong>sidious problem. Emotional abuse encompasses<br />

several <strong>for</strong>ms of childhood maltreatment, such as<br />

witness<strong>in</strong>g domestic violence (WDV) and exposure to verbal<br />

aggression (VA) (4). Generally, exposure to VA has received<br />

little attention as a specific <strong>for</strong>m of abuse, though we recently<br />

reported that young adults exposed to parental verbal abuse<br />

(PVA) had elevated symptoms of depression, anxiety, and<br />

dissociation. Effect sizes <strong>for</strong> PVA were comparable with those<br />

<strong>for</strong> WDV or extrafamilial CSA (5).<br />

From the Department of Psychiatry (JC, BJ, MLR, AMP, MHT), Harvard Medical<br />

School, Boston, Massachusetts; Developmental Biopsychiatry Research<br />

Program (JC, AMP, MHT) and Bra<strong>in</strong> Imag<strong>in</strong>g Center (MLR), McLean<br />

Hospital, Belmont, Massachusetts; Department of Psychiatry (JC), Catholic<br />

University of Korea, Daejeon St. Mary’s Hospital, and Department of<br />

Psychiatry (BJ), Eulji University Hospital, Daejeon, South Korea.<br />

Address repr<strong>in</strong>t requests to Mart<strong>in</strong> H. Teicher, M.D., Ph.D., Developmental<br />

Biopsychiatry Research Program (DBRP), McLean Hospital, Belmont, MA<br />

02478; E-mail: mart<strong>in</strong>_teicher@hms.harvard.edu<br />

Received October 20, 2007; revised May 29, 2008; accepted June 18, 2008.<br />

Understand<strong>in</strong>g the importance of emotional abuse is critically<br />

important, as parents, physicians, teachers, and other <strong>in</strong>dividuals<br />

responsible <strong>for</strong> the well-be<strong>in</strong>g of children are generally unaware<br />

of the potential consequences of exposure to PVA (6,7). Identify<strong>in</strong>g<br />

neurobiological correlates of exposure to PVA may lead to<br />

important changes <strong>in</strong> parental behavior and provide a more<br />

articulate framework <strong>for</strong> explor<strong>in</strong>g the relationship between<br />

psychopathology and parent<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

To assess the potential consequences of PVA, we conducted<br />

a diffusion tensor imag<strong>in</strong>g (DTI) analysis of white matter (WM)<br />

tract <strong>in</strong>tegrity <strong>in</strong> young adults with and without high-level<br />

exposure to PVA. <strong>Abnormalities</strong> <strong>in</strong> the corpus callosum, the<br />

bra<strong>in</strong>’s most extensive WM tract, have been observed with<br />

conventional imag<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> children and adolescents exposed to<br />

physical abuse (PA), CSA, or neglect (8–11). We recently found<br />

that corpus callosum size was most significantly altered by CSA<br />

that occurred at 9 to 10 years of age (12). Diffusion tensor<br />

imag<strong>in</strong>g, which analyzes the restricted diffusion of water molecules,<br />

provides a more detailed assessment of fiber tracts than<br />

conventional magnetic resonance imag<strong>in</strong>g (MRI) (13) and has<br />

emerged as a powerful new technique <strong>for</strong> study<strong>in</strong>g the role of<br />

neural connectivity <strong>in</strong> health and disease (13).<br />

A priori, we hypothesized that exposure to PVA would affect<br />

the <strong>in</strong>tegrity of left hemisphere pathways <strong>in</strong>volved with process<strong>in</strong>g<br />

language, as well as fiber tracts <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> emotional<br />

regulation. We now report the first evidence of a potential<br />

deleterious effect of ridicule, humiliation, and disda<strong>in</strong> on bra<strong>in</strong><br />

connectivity.<br />

Methods and Materials<br />

Participants and Screen<strong>in</strong>g<br />

The McLean Hospital Institutional Review Board approved all<br />

procedures. The purpose and mean<strong>in</strong>g of this study was expla<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

to subjects, who provided written <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>med consent. To<br />

0006-3223/09/$36.00<br />

BIOL PSYCHIATRY 2009;65:227–234<br />

doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.06.022 © 2009 Society of Biological Psychiatry

228 BIOL PSYCHIATRY 2009;65:227–234 J. Choi et al.<br />

be eligible, subjects had to be between 18 and 25 years of age,<br />

right-handed, unmedicated, with a self-reported history of exposure<br />

to PVA but to no other <strong>for</strong>m of early stress or trauma, or<br />

healthy control subjects without such exposure. Subjects were<br />

excluded who had a history of CSA, WDV, parental loss, neglect,<br />

or significant PA, as well as exposure to war, gang violence,<br />

motor vehicle accidents, near drown<strong>in</strong>g, fires, natural disasters,<br />

or animal attacks. Subjects were also required to be free from any<br />

neurological disease or <strong>in</strong>sult, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g any degree of head<br />

trauma result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> loss of consciousness. Subjects were excluded<br />

with a history of premature birth or birth complications,<br />

a history of be<strong>in</strong>g shaken <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>fancy or childhood, maternal<br />

substance abuse dur<strong>in</strong>g pregnancy, or medical disorders that<br />

could affect bra<strong>in</strong> development. Subjects selected had no more<br />

than m<strong>in</strong>imal history of substance use or alcohol use and tested<br />

negative <strong>for</strong> drugs and alcohol on each visit.<br />

Potential subjects responded to advertisements with the title<br />

“Memories of Childhood”; were briefly screened by phone <strong>for</strong><br />

age, handedness, and medication status; and then completed an<br />

onl<strong>in</strong>e assessment <strong>in</strong>strument with 2342 entry fields that provide<br />

a vast array of <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation regard<strong>in</strong>g childhood history, development,<br />

and symptomatology. Degree of exposure to PVA was<br />

assessed us<strong>in</strong>g the verbal abuse scale (VAS) (5). Subjects with<br />

high-level exposure to PVA were required to have a mean<br />

parental VAS score 40, which corresponds to weekly–monthly<br />

exposure to various <strong>for</strong>ms of criticism, scold<strong>in</strong>g, ridicule, or<br />

yell<strong>in</strong>g and scream<strong>in</strong>g or a maximal parent VAS score (either<br />

mother or father) 50. This degree of exposure to PVA occurred<br />

<strong>in</strong> 16.7% of onl<strong>in</strong>e respondents with no history of CSA, PA, or<br />

WDV. Control subjects had no exposure to PVA and no history of<br />

DSM-IV Axis I psychiatric disorders on structured diagnostic<br />

<strong>in</strong>terview (14).<br />

From 1271 respondents who completed onl<strong>in</strong>e evaluations,<br />

31 subjects exposed to PVA and 31 potential control subjects<br />

were <strong>in</strong>vited to the laboratory <strong>for</strong> detailed <strong>in</strong>terviews. Highquality<br />

DTI scans, free from motion artifacts, were collected on<br />

16 subjects with PVA (4 male subjects/12 female subjects, mean<br />

age 21.9 2.4 years) and 16 healthy control subjects (5 male<br />

control subjects/11 female control subjects, 21.0 1.6 years),<br />

who met our rigorous <strong>in</strong>clusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1).<br />

Parental verbal abuse subjects had average parental VAS scores<br />

of 42 9 and maximal parental VAS scores of 66 12 versus<br />

12 7 and 16 7 <strong>for</strong> control subjects, respectively. Onset of<br />

PVA was at 6.9 3.2 years (range 3–13 years of age). Seven<br />

subjects cont<strong>in</strong>ued to experience PVA. It had abated 4.3 1.7<br />

years ago <strong>in</strong> the rema<strong>in</strong>der. Hence, it had been a chronic stressor,<br />

last<strong>in</strong>g an average of 12.3 4.1 years. Forty-four percent of the<br />

PVA subjects had a history of depression, though none currently<br />

met full criteria. Three of the PVA subjects had current anxiety<br />

disorders (two with generalized anxiety, one with panic and<br />

obsessive-compulsive disorders) and another had attention-deficit/hyperactivity<br />

disorder and a history of phobias. Parental<br />

verbal abuse subjects and control subjects did not differ <strong>in</strong><br />

paternal or maternal education levels (Table 1) but differed<br />

substantially <strong>in</strong> perceived f<strong>in</strong>ancial sufficiency (Mann-Whitney U<br />

Test 50, p .002). Half of the PVA subjects felt they came from<br />

families that had less than enough or much less than enough<br />

money to meet their family’s needs. None of the control subjects<br />

came from families with a perception of less than enough money,<br />

and 62.5% came from families with more than enough or much<br />

more than enough money to meet their family’s needs.<br />

www.sobp.org/journal<br />

Table 1. Subject Characteristics<br />

Characteristic<br />

PVA Subjects<br />

(n 16)<br />

Healthy Control<br />

Subjects<br />

(n 16) p Value<br />

Age, Mean (SD), Years 21.9 (2.4) 21.0 (1.6) .242<br />

Sex, No. M/F 4/12 5/11 .78 a<br />

VIQ, Mean (SD) 121 (13) 129 (11) .094<br />

PIQ, Mean (SD) 120 (11) 116 (9) .295<br />

FSIQ, Mean (SD) 122 (12) 124 (11) .610<br />

Mother VAS, Mean (SD) 56 (24) 14 (9) .001 b<br />

Father VAS, Mean (SD) 31 (27) 11 (7) .015 b<br />

Maximal (mother or father)<br />

VAS, Mean (SD) 66 (12) 16 (7) .001 b<br />

Mother Education, mean<br />

(SD), Years 15.6 (2.3) 16.3 (2.3) .399<br />

Father Education, mean<br />

(SD), Years 16.6 (3.4) 16.7 (3.1) .914<br />

Perceived F<strong>in</strong>ancial<br />

Sufficiency 2.7 (1.0) 3.8 (0.7) .002 b<br />

F, female; FSIQ, full-scale IQ; M, male; PIQ, per<strong>for</strong>mance IQ; PVA, parental<br />

verbal abuse; VAS, verbal abuse score; VIQ, verbal IQ.<br />

a 2 test. All other p values are by t test.<br />

b Statistically significant.<br />

Cl<strong>in</strong>ical Measures<br />

All subjects were adm<strong>in</strong>istrated structured diagnostic <strong>in</strong>terviews<br />

(14) <strong>for</strong> current and lifetime history of DSM-IV Axis I and<br />

II psychiatric disorders. History of exposure to VA and to no<br />

other <strong>for</strong>ms of maltreatment were confirmed us<strong>in</strong>g the 100-item<br />

semistructured Traumatic Antecedents Interview (15). Verbal IQ<br />

and Verbal Comprehension Index (VCI) were assessed us<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Third Edition (WAIS-III) (16).<br />

Rat<strong>in</strong>gs of dissociation, limbic irritability, depression, and anxiety<br />

were obta<strong>in</strong>ed us<strong>in</strong>g the Dissociative Experience Scale (17),<br />

Limbic System Checklist-33 (18), and Kellner’s Symptom Questionnaire<br />

(19), respectively. These measures were selected, a<br />

priori, as we had previously reported that they were markedly<br />

elevated <strong>in</strong> a separate sample of young adults with a history of<br />

exposure to PVA (5).<br />

Magnetic Resonance Imag<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Image Acquisition. Magnetic resonance imag<strong>in</strong>g exam<strong>in</strong>ations<br />

were conducted at the Bra<strong>in</strong> Imag<strong>in</strong>g Center at McLean<br />

Hospital. The head was stabilized with cushions and tape be<strong>for</strong>e<br />

scann<strong>in</strong>g to help m<strong>in</strong>imize movement. Multiple diffusionweighted<br />

images (DWIs), with 12 encod<strong>in</strong>g directions and an<br />

additional T2-weighted scan, were acquired us<strong>in</strong>g a 3T Siemens<br />

Trio scanner (Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany)<br />

with standard s<strong>in</strong>gle-shot, sp<strong>in</strong>-echo, echo-planar acquisition<br />

sequence with eddy current balanced diffusion weight<strong>in</strong>g gradient<br />

pulses to reduce distortion (20). Scan parameters were b <br />

1000 sec/mm 2 ; echo time (TE)/repetition time (TR) 81 msec/5<br />

sec; matrix 128 128 on 220 mm 220 mm field of view<br />

(FOV); slices 5 mm without gap result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> voxels of 1.71875 <br />

1.71875 5 mm. Four magnitude averages provided sufficient<br />

signal-to-noise ratios. Volumetric T1-weighted anatomic reference<br />

images were acquired us<strong>in</strong>g a magnetization-prepared<br />

rapid gradient-echo (MP-RAGE) sequence (TE/TR/<strong>in</strong>version time<br />

[TI] 2.74 msec/2.1 sec/1/1 sec; 256 256 128 matrix <strong>for</strong> 1 <br />

1 1.3 mm voxels).<br />

Image Process<strong>in</strong>g and Analysis. Diffusion tensor imag<strong>in</strong>g<br />

preprocess<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g skull stripp<strong>in</strong>g us<strong>in</strong>g the bra<strong>in</strong> extraction<br />

tool (BET) and eddy-current correction, were per<strong>for</strong>med

J. Choi et al. BIOL PSYCHIATRY 2009;65:227–234 229<br />

us<strong>in</strong>g the Functional MRI of the Bra<strong>in</strong> (FMRIB) Software Library<br />

(FSL) (FMRIB Centre, University of Ox<strong>for</strong>d, Ox<strong>for</strong>d, United<br />

K<strong>in</strong>gdom). A diffusion tensor model was fit to each voxel to<br />

create fractional anisotropy (FA) images. The tract-based spatial<br />

statistics (TBSS) tool <strong>in</strong> FSL was used to calculate tract-based<br />

differences <strong>in</strong> FA values between the PVA group and control<br />

subjects (Supplement 1). <strong>Tract</strong>-based spatial statistics is a new<br />

approach <strong>for</strong> group difference determ<strong>in</strong>ation that uses an anatomically<br />

based, carefully tuned nonl<strong>in</strong>ear registration procedure<br />

to project results onto an alignment-<strong>in</strong>variant tract representation<br />

(the mean FA skeleton) <strong>for</strong> voxelwise analysis of multisubject<br />

diffusion data (21). <strong>Tract</strong>-based spatial statistics computes a<br />

group mean FA skeleton, which represents the centers of all fiber<br />

bundles that are common to the subjects <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> the study<br />

(21). Each subject’s aligned FA image was projected onto the<br />

skeleton by fill<strong>in</strong>g the skeleton with FA values from the nearest<br />

relevant tract center. Group-based skeletonized FA maps were<br />

used <strong>for</strong> statistical analysis, apply<strong>in</strong>g a General L<strong>in</strong>ear Model<br />

covariate analysis. This analysis adjusted <strong>for</strong> effects of gender,<br />

age, maternal and paternal education, and household f<strong>in</strong>ances.<br />

The latter three measures were <strong>in</strong>cluded as separate covariates,<br />

as research suggests that measures of <strong>in</strong>come and education may<br />

serve as more robust correlates of child development than a<br />

composite measure of socioeconomic status (22). Requisite<br />

significance level was set, a priori, to detect regions of at least 30<br />

consecutive voxels <strong>in</strong> which uncorrected group differences<br />

exceeded a threshold of p .0005, to balance risk of type I and<br />

type II errors.<br />

Exploratory correlation analyses assessed whether regional<br />

differences <strong>in</strong> FA could potentially account <strong>for</strong> a significant<br />

portion of the variance <strong>in</strong> prespecified symptom rat<strong>in</strong>gs. Similarly,<br />

exploratory correlation analyses were per<strong>for</strong>med <strong>for</strong> possible<br />

associations between FA <strong>in</strong> identified regions and verbal IQ<br />

and VCI on the WAIS-III (16). We hypothesized that exposure to<br />

aversive or punish<strong>in</strong>g verbal stimuli may exert a counterproductive<br />

effect on the development of language skills, based on the<br />

assumption that the development of l<strong>in</strong>guistic skills depends on<br />

exposure to engag<strong>in</strong>g and enjoyable aspects of language and<br />

communication. The idea that language and cognitive abilities<br />

may suffer if the communication is not engag<strong>in</strong>g (flat, monotone,<br />

not age-appropriate) is supported by studies that report deficits<br />

<strong>in</strong> language skills and cognitive abilities <strong>in</strong> children with depressed<br />

mothers (23) who tend to communicate with their<br />

children <strong>in</strong> this manner. The idea that exposure to violence can<br />

<strong>in</strong>terfere with neurocognitive development is supported by<br />

studies report<strong>in</strong>g significant IQ and read<strong>in</strong>g deficits <strong>in</strong> children<br />

who witnessed domestic violence or were exposed to other<br />

<strong>for</strong>ms of aggression (24,25).<br />

Both cases and control subjects were <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> the correlation<br />

analyses, as we were <strong>in</strong>terested <strong>in</strong> assess<strong>in</strong>g potential<br />

functional correlates of these del<strong>in</strong>eated WM segments <strong>in</strong> the<br />

general population. Although subjects were dichotomized <strong>in</strong>to<br />

PVA and control groups us<strong>in</strong>g cutoff scores, all subjects had<br />

some degree of exposure, and our selection criteria were completely<br />

<strong>in</strong>clusive regard<strong>in</strong>g degree of exposure. With<strong>in</strong> the actual<br />

sample, there was only a 2.5-po<strong>in</strong>t gap between lowest mean<br />

VAS score <strong>for</strong> PVA subject and highest VAS score <strong>for</strong> control<br />

subjects. In short, the entire range of VAS scores was sampled<br />

with no significant gap <strong>in</strong> scores between groups, and the<br />

distribution of PVA scores <strong>for</strong> the entire sample did not depart<br />

significantly from a s<strong>in</strong>gle normal distribution (Kolomogorov-<br />

Smirnov test: z 1.022, p .247). Second, most of the subjects<br />

<strong>in</strong> our PVA group would be control subjects <strong>in</strong> other studies.<br />

Third, fiber tract regions identified by TBSS had FA values that<br />

showed a strong rank-order correlation with degree of exposure<br />

to PVA, and FA values <strong>for</strong> the entire sample were well characterized<br />

by s<strong>in</strong>gle normal distributions. Hence, although we<br />

dichotomized subjects, it appears that we were deal<strong>in</strong>g less with<br />

a threshold or stair-step effect than with a graded response<br />

between exposure to PVA and regional FA. Thus, we approached<br />

the correlation analysis from the perspective of a s<strong>in</strong>gle<br />

population of healthy young adult subjects with different degrees<br />

of exposure to PVA and differ<strong>in</strong>g FA values <strong>in</strong> the identified WM<br />

tract segments. Exam<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g correlations <strong>in</strong> only one group restricts<br />

the range of the <strong>in</strong>dependent variable and can seriously<br />

bias results (26). Spearman rank-order correlation was used to<br />

assess the degree of relationship between variables, to m<strong>in</strong>imize<br />

concerns about homoscedasticity, and the impact of group<br />

differences on these associations.<br />

<strong>Tract</strong> Trac<strong>in</strong>g. Probabilistic tract trac<strong>in</strong>g was used to help<br />

identify the most likely fiber tract(s) pass<strong>in</strong>g through WM regions<br />

identified by TBSS as differ<strong>in</strong>g significantly between groups.<br />

These WM areas were projected back from Montreal Neurological<br />

Institute (MNI) space to <strong>in</strong>dividual diffusion space and used<br />

as seed<strong>in</strong>g po<strong>in</strong>ts to trace fiber tracts that passed through this<br />

region <strong>in</strong> representative subjects. Be<strong>for</strong>e probabilistic track<strong>in</strong>g,<br />

Markov Cha<strong>in</strong> Monte Carlo sampl<strong>in</strong>g was run to build up distributions<br />

of diffusion parameters at each voxel us<strong>in</strong>g BEDPOST<br />

(Bayesian Estimation of Diffusion Parameters Obta<strong>in</strong>ed us<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Sampl<strong>in</strong>g Techniques) (27). Probabilistic tractography was per<strong>for</strong>med<br />

us<strong>in</strong>g FSL.<br />

Detailed tractography was then per<strong>for</strong>med <strong>in</strong> representative<br />

PVA and control subjects us<strong>in</strong>g MedINRIA (Medical Image Navigation<br />

and Research Tool by INRIA, Cedex, France; http://<br />

www.sop.<strong>in</strong>ria.fr/asclepios/software/-MedINRIA/) to better localize<br />

regions of statistically significant differences (determ<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

by TBSS) along the likely pathways identified by probabilistic<br />

tract trac<strong>in</strong>g. Regions of <strong>in</strong>terest were selected on the directionally<br />

encoded tensor maps similar to the methods described by<br />

Vernooij et al. (28) and Concha et al. (29). M<strong>in</strong>imum fiber length<br />

was set to 5 mm and the smoothness of reconstructed fiber to 20.<br />

Other parameters <strong>for</strong> fiber track<strong>in</strong>g used MedINRIA default<br />

values. Track<strong>in</strong>g of fibers term<strong>in</strong>ated when FA fell below a<br />

threshold of .18.<br />

Results<br />

<strong>Tract</strong>-based spatial statistics identified three portions of the FA<br />

skeleton with reduced FA that exceeded preselected criteria <strong>for</strong><br />

significance and voxel size. The largest and most significant<br />

portion [F(1,26) 29.12, p .00001; voxel size 49; MIN<br />

coord<strong>in</strong>ates x 44, y 32, z 3; Figures 1 and 2] was<br />

located <strong>in</strong> the left superior temporal gyrus and identified by tract<br />

trac<strong>in</strong>g as the arcuate fasciculus. Fractional anisotropy values <strong>in</strong><br />

this region, covaried <strong>for</strong> age, gender, parental education, and<br />

family f<strong>in</strong>ancial status, were 22% lower <strong>in</strong> the PVA group than<br />

control subjects. There was a strong correlation between FA<br />

values and average parental VAS score (r s .701, p .001).<br />

Multiple regression analysis <strong>in</strong>dicated that FA values <strong>in</strong> this<br />

region correlated with levels of both maternal ( .730, p <br />

.001) and paternal ( .391, p .002) VA. Fractional<br />

anisotropy values <strong>in</strong> this region were significantly correlated with<br />

verbal IQ (r s .411, p .024) and VCI (r s .437, p .016).<br />

Fractional anisotropy, <strong>in</strong> the second region identified, was<br />

reduced by 26.2% <strong>in</strong> the PVA group [F(1,29) 24.4, p .0002;<br />

voxel size 30; MIN coord<strong>in</strong>ates x 28, y 51, z 1;<br />

www.sobp.org/journal

230 BIOL PSYCHIATRY 2009;65:227–234 J. Choi et al.<br />

Figure 1. Coronal, axial, and sagittal location of white matter tract region 1 (shown <strong>in</strong> red, centered at x 44, y 32, z 3) that differed most significantly<br />

<strong>in</strong> fractional anisotropy (FA) between subjects with history of exposure to high levels of parental verbal aggression and healthy control subjects. Region 1 is<br />

located <strong>in</strong> the left superior temporal gyrus and conta<strong>in</strong>s fibers from the arcuate fasciculus. Green shows the mean FA skeleton (which represents the centers<br />

of white matter fiber bundles that are common to the subjects <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> this study). The background images are MNI152 templates. MNI, Montreal<br />

Neurological Institute.<br />

Figures 2 and 3]. This region was located <strong>in</strong> the left fusi<strong>for</strong>m gyrus<br />

by the posterior tail of the hippocampus and appeared to lie<br />

along a portion of the c<strong>in</strong>gulum bundle. Fractional anisotropy<br />

correlated substantially with average levels of parental VAS (r s <br />

.801, p .001) and correlated with both maternal ( .803,<br />

p .001) and paternal ( .470, p .001) VA rat<strong>in</strong>gs.<br />

Self-report rat<strong>in</strong>gs of depression (r s .504, p .004), dissociation<br />

(r s .373, p .05), and limbic irritability (r s .602,<br />

p .001) were <strong>in</strong>versely correlated with FA values <strong>in</strong> this region.<br />

Fractional anisotropy <strong>in</strong> the third region identified was reduced<br />

by 23.8% <strong>in</strong> the PVA group [F(1,29) 17.8, p .0003;<br />

voxel size 37; MIN coord<strong>in</strong>ates x 3, y 14, z 22;<br />

Figures 2 and 4] and was located around the left body of the<br />

<strong>for</strong>nix. Fractional anisotropy was not <strong>in</strong>fluenced by any of the<br />

covariates (all p values .5) but correlated with average parental<br />

VAS (r s .524, p .002). Multiple regression revealed significant<br />

correlations with maternal VAS ( .589, p .001) but not<br />

paternal VAS ( .120, p .4). Region 3 FA values correlated<br />

with self-report rat<strong>in</strong>gs of somatization (r s .389, p .03) and<br />

showed a trend level association with anxiety (r s .311, p <br />

.09). Bl<strong>in</strong>d manual measures of FA were per<strong>for</strong>med to verify<br />

results of TBSS <strong>for</strong> this small region. Manual <strong>for</strong>nix FA measures<br />

correlated strongly with TBSS (r .844, p 10 8 ). They were<br />

reduced by 21.3% <strong>in</strong> the PVA group [F(1,29) 10.36, p .003]<br />

and correlated significantly with maternal VAS (r s .357, p <br />

.05) but not paternal VAS (r s .071, p .6).<br />

One concern <strong>in</strong> exam<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the potential effects of exposure to<br />

PVA on fiber tracts is that PVA may be due to parental mental<br />

illness and differences observed may be more a consequence of<br />

heredity than exposure. To test this possibility, we reexam<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

the association covary<strong>in</strong>g <strong>for</strong> history of maternal and paternal<br />

mental illness. Scores of 0 were given <strong>for</strong> no history, 1 <strong>for</strong> a<br />

def<strong>in</strong>ite history, and .5 <strong>for</strong> a possible history. Seventy-five percent<br />

of control subjects <strong>in</strong>dicated that neither parent had a def<strong>in</strong>ite or<br />

possible history of mental illness versus only 38% of PVA<br />

subjects. Group differences rema<strong>in</strong>ed significant after adjustment:<br />

region 1 [F(1,24) 19.41, p .0002]; region 2 [F(1,27) <br />

14.14, p .001]; and region 3 [F(1,27) 10.37, p .003],<br />

suggest<strong>in</strong>g that the association between exposure to PVA and<br />

reduced regional FA was not simply an artifact of parental mental<br />

illness. The most significant predictor of PVA was f<strong>in</strong>ancial<br />

<strong>in</strong>sufficiency, which was controlled <strong>for</strong> <strong>in</strong> all analyses.<br />

Detailed tractography illustrates the apparent location of statistically<br />

significant differences <strong>in</strong> FA, derived by TBSS, along likely fiber<br />

tracts pass<strong>in</strong>g through these regions. As seen <strong>in</strong> Figure 5, fibers<br />

pass<strong>in</strong>g through region 1 were arcuate fasciculus fibers project<strong>in</strong>g<br />

between temporal and frontal regions, most specifically the more<br />

anterior fibers from the caudal superior temporal cortex passed<br />

through the region. Likely fibers pass<strong>in</strong>g through region 2<br />

belonged to the c<strong>in</strong>gulum bundle, and TBSS del<strong>in</strong>eated fibers<br />

project<strong>in</strong>g to the hippocampal region (Figure 6). Fibers pass<strong>in</strong>g<br />

through region 3 were traced <strong>in</strong> all subjects and observed to<br />

Figure 2. Scatterplot show<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>dividual differences <strong>in</strong> fractional anisotropy between subjects with a history of exposure to high levels of parental verbal<br />

aggression and healthy control subjects <strong>in</strong> (A) region 1 (arcuate fasciculus left superior temporal gyrus); (B) region 2 (c<strong>in</strong>gulum bundle <strong>in</strong> the left fusi<strong>for</strong>m<br />

gyrus by the posterior tail of the hippocampus); and (C) region 3 (left <strong>for</strong>nix by corpus callosum).<br />

www.sobp.org/journal

J. Choi et al. BIOL PSYCHIATRY 2009;65:227–234 231<br />

Figure 3. Coronal, axial, and sagittal location of white matter tract region 2 (shown <strong>in</strong> red, centered at x 28, y 51, z 1) that differed significantly <strong>in</strong><br />

fractional anisotropy (FA) between subjects with history of exposure to high levels of parental verbal aggression and healthy control subjects. Region 2 is<br />

located <strong>in</strong> the left fusi<strong>for</strong>m gyrus by the posterior tail of the hippocampus and conta<strong>in</strong>s fibers from the c<strong>in</strong>gulum bundle. Green shows the mean FA skeleton.<br />

The background images are MNI152 templates. MNI, Montreal Neurological Institute.<br />

follow the course of the <strong>for</strong>nix, which connects the hippocampus<br />

to the mammillary body and septal nucleus (Figure 7).<br />

Discussion<br />

This study provides prelim<strong>in</strong>ary evidence that exposure to<br />

PVA is associated with alteration <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>tegrity of neural<br />

pathways. Region 1 was located <strong>in</strong> the left superior temporal<br />

gyrus and appeared to consist of long association fibers constitut<strong>in</strong>g<br />

the arcuate fasciculus. Traditionally, the arcuate fasciculus<br />

is known as the fiber tract connect<strong>in</strong>g Wernicke’s area <strong>in</strong> the<br />

temporoparietal junction with Broca’s area <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>ferior frontal<br />

gyrus. Recent anatomical studies suggest that the arcuate fasciculus<br />

connects caudal superior temporal area 22 with frontal lobe<br />

areas 8 and 46 and provides a pathway <strong>for</strong> the prefrontal cortex<br />

to receive and modulate auditory <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation (30). Fractional<br />

anisotropy <strong>in</strong> region 1 correlated with verbal IQ and VCI.<br />

Parental verbal abuse subjects and control subjects did not differ<br />

to a significant degree <strong>in</strong> verbal IQ or VCI (Table 1), suggest<strong>in</strong>g<br />

that the effects were relatively subtle. Parental verbal abuse<br />

subjects differed from control subjects <strong>in</strong> two of seven verbal<br />

subtests of the WAIS-III: comprehension (which tests ability to<br />

deal with abstract social conventions, rules, and expressions) and<br />

similarities (which tests abstract verbal reason<strong>in</strong>g). Comprehension<br />

subtest scores correlated particularly strongly with reduced<br />

FA <strong>in</strong> region 1 (r s .606, p .001). Breier et al. (31) recently<br />

reported that comprehension deficits after stroke were specifically<br />

associated with lower FA values <strong>in</strong> the arcuate fasciculus of<br />

the left hemisphere.<br />

Region 2 was located <strong>in</strong> the left fusi<strong>for</strong>m gyrus by the<br />

posterior tail of the hippocampus and appeared to conta<strong>in</strong> fibers<br />

from the ventral part of the c<strong>in</strong>gulum bundle. Left-sided reduction<br />

<strong>in</strong> FA through three of four subregions of the c<strong>in</strong>gulum<br />

bundle has been observed <strong>in</strong> patients with posttraumatic stress<br />

disorder (32), <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g that this is probably a stress-susceptible<br />

structure. Overall, reduced FA <strong>in</strong> region 2 was associated with<br />

elevated scores of limbic irritability, dissociation, and depression.<br />

Limbic irritability is a term we have used (5,18) to describe the<br />

presence of symptoms often seen <strong>in</strong> patients with temporal lobe<br />

epilepsy, such as paroxysmal somatic disturbances, brief halluc<strong>in</strong>atory<br />

events, visual illusions, automatisms, and dissociative<br />

disturbances (33). The c<strong>in</strong>gulum bundle is the most prom<strong>in</strong>ent<br />

tract of the limbic lobe and connects the limbic lobe with the<br />

neocortex, particularly the c<strong>in</strong>gulate gyrus.<br />

Region 3 was located <strong>in</strong> the left <strong>for</strong>nix, and reduced FA <strong>in</strong> this<br />

segment was associated with <strong>in</strong>creased rat<strong>in</strong>gs of somatization<br />

and anxiety. The septohippocampal system, connected together<br />

via the <strong>for</strong>nix, plays a major role <strong>in</strong> the mediation of anxiety (34).<br />

Interest<strong>in</strong>gly, the hippocampus receives seroton<strong>in</strong> fibers from the<br />

midbra<strong>in</strong> raphe via two pathways: the c<strong>in</strong>gulum bundle (which<br />

predom<strong>in</strong>antly <strong>in</strong>nervates dorsal hippocampus) and the <strong>for</strong>nix<br />

(which <strong>in</strong>nervates all portions) (35,36). Hence, two of the fiber<br />

tracts with segments of reduced FA <strong>in</strong> PVA subjects provide<br />

pathways <strong>for</strong> seroton<strong>in</strong> fibers to <strong>in</strong>nervate the hippocampus.<br />

Although DTI studies are rapidly <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g our understand<strong>in</strong>g<br />

of the effects of disease processes on WM tracts, caution is<br />

required <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>terpret<strong>in</strong>g reductions <strong>in</strong> FA. The analytical technique<br />

employed relies on 1 mm resampl<strong>in</strong>g of data to determ<strong>in</strong>e<br />

local maxima of FA values. As such, it is sensitive to structures<br />

whose size is small compared with the orig<strong>in</strong>al echo-planar<br />

imag<strong>in</strong>g (EPI) image voxel size or to tracts that are adjacent to<br />

Figure 4. Coronal, axial, and sagittal location of white matter tract region 3 (shown <strong>in</strong> red, centered at x 3, y 14, z 22) that differed significantly <strong>in</strong><br />

fractional anisotropy (FA) between subjects with history of exposure to high levels of parental verbal aggression and healthy control subjects. Region 3<br />

conta<strong>in</strong>s fibers from the body of the left <strong>for</strong>nix. Green shows the mean FA skeleton. The background images are MNI152 templates. MNI, Montreal Neurological<br />

Institute.<br />

www.sobp.org/journal

232 BIOL PSYCHIATRY 2009;65:227–234 J. Choi et al.<br />

Figure 5. Detailed tractography of left arcuate fasciculus fibers <strong>in</strong> a representative<br />

subject color coded by fiber direction. Yellow region marks segment<br />

of the pathway del<strong>in</strong>eated by TBSS as hav<strong>in</strong>g significantly lower FA <strong>in</strong><br />

subjects with PVA versus control subjects. FA, fractional anisotropy; PVA,<br />

parental verbal abuse; TBSS, tract-based spatial statistics.<br />

sharp white/nonwhite matter boundaries and their resultant<br />

partial volume effects. This is of potential concern <strong>in</strong> the analysis<br />

of FA values <strong>for</strong> regions 2 and 3. The left fusi<strong>for</strong>m gyrus is<br />

adjacent to the atrium of the lateral ventricle, and the left <strong>for</strong>nix<br />

is a relatively small WM tract situated with<strong>in</strong> the lateral ventricle.<br />

<strong>Tract</strong>-based spatial statistics reduces the challenges of alignment<br />

<strong>in</strong> FA images without <strong>in</strong>troduc<strong>in</strong>g smooth<strong>in</strong>g and calculates<br />

group FA values us<strong>in</strong>g voxels from the center of each subject’s<br />

tract to m<strong>in</strong>imize <strong>in</strong>clusion of voxels that border sharp nonwhite<br />

matter boundaries. However, partial volume effects are a magnetic<br />

resonance (MR) acquisition problem, limited by signal to<br />

noise, and not correctable through analysis. Fractional anisotropy<br />

values observed <strong>in</strong> these regions were very similar to<br />

previously published FA values <strong>for</strong> healthy control subects<br />

(37–39). The particularly low FA values observed <strong>in</strong> region 2 may<br />

arise as consequence of divergent cross<strong>in</strong>g of fibers pass<strong>in</strong>g<br />

through this region. The significance of the group differences<br />

and the strength and appropriateness of the anatomical-functional<br />

correlations suggest that FA differences <strong>in</strong> these regions<br />

represent areas of reduced WM <strong>in</strong>tegrity and resultant psychopathological<br />

effects. Further confirmation will need to occur<br />

Figure 6. Detailed tractography of left c<strong>in</strong>gulum bundle fibers <strong>in</strong> a representative<br />

subject color coded by fiber direction. Yellow region marks segment<br />

of the pathway del<strong>in</strong>eated by TBSS as hav<strong>in</strong>g significantly lower FA <strong>in</strong><br />

subjects with PVA versus control subjects. FA, fractional anisotropy; PVA,<br />

parental verbal abuse; TBSS, tract-based spatial statistics.<br />

www.sobp.org/journal<br />

Figure 7. Detailed tractography of left <strong>for</strong>nix fibers <strong>in</strong> a representative<br />

subject color coded by fiber direction. Yellow region marks segment of the<br />

pathway del<strong>in</strong>eated by TBSS as hav<strong>in</strong>g significantly lower FA <strong>in</strong> subjects<br />

with PVA versus control subjects. FA, fractional anisotropy; PVA, parental<br />

verbal abuse; TBSS, tract-based spatial statistics.<br />

through replication <strong>in</strong> larger samples and through ref<strong>in</strong>ements <strong>in</strong><br />

resolution (40).<br />

Curiously, TBSS identified group differences <strong>in</strong> FA along<br />

specific portions of fiber tracts but did not del<strong>in</strong>eate the entire<br />

tract. This proclivity to identify segments is a property of the<br />

program (seen <strong>in</strong> the representative image <strong>in</strong> the TBSS user<br />

manual) and is determ<strong>in</strong>ed to a significant degree by the criteria<br />

set <strong>for</strong> cluster size and significance. However, entire tracts were<br />

not del<strong>in</strong>eated <strong>in</strong> this sample even when significance and cluster<br />

size levels were lowered. We suspect that reduced FA is restricted<br />

to a fraction of the fibers constitut<strong>in</strong>g the tract and that<br />

regions of reduced FA become apparent along segments of the<br />

tract where these particular fibers enter or exit the pathway or<br />

when these fibers represent a substantial proportion of the<br />

pathway due to the exit<strong>in</strong>g of other fibers. Why PVA is associated<br />

with reduced FA is unclear. It is unlikely that PVA directly affects<br />

the number of axons, as this is generally established early <strong>in</strong><br />

childhood. Parental verbal abuse, however, may affect axon<br />

diameter, microtubular structure, and the proportion of myel<strong>in</strong>ated<br />

and unmyel<strong>in</strong>ated fibers that constitute a component of the<br />

pathway, as these properties are established later <strong>in</strong> development<br />

(41) and appear susceptible to effects of experience dur<strong>in</strong>g<br />

preadolescent and peripubertal periods (42).<br />

The current study is limited by the modest sample size and by<br />

the rigorous selection criteria. Parental verbal abuse subjects<br />

studied were healthier than those previously assessed (5) and<br />

had average IQ scores higher than the general population but<br />

comparable with those of college graduates. These subjects were<br />

not representative of <strong>in</strong>dividuals typically exposed to emotional<br />

maltreatment, who often experience other <strong>for</strong>ms of abuse and<br />

show greater sequelae. Subjects were selected to provide a test of<br />

the hypothesis unconfounded (to the greatest degree feasible) by<br />

exposure to other <strong>for</strong>ms of early stress, medications, or agents<br />

that could affect bra<strong>in</strong> development. Identify<strong>in</strong>g abnormalities <strong>in</strong>

J. Choi et al. BIOL PSYCHIATRY 2009;65:227–234 233<br />

such a select group provides a conservative test of the hypothesis.<br />

We suspect that more severely affected <strong>in</strong>dividuals would<br />

have had more extensive f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs, though it may have been<br />

harder to attribute their f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs to PVA.<br />

Overall, results from this study support a hypothesis that the<br />

bra<strong>in</strong> is chiseled <strong>in</strong> precise ways by exposure to adverse early<br />

experience. Analysis of neural connectivity patterns provides<br />

prelim<strong>in</strong>ary but <strong>in</strong>trigu<strong>in</strong>g evidence that the arcuate fasciculus,<br />

c<strong>in</strong>gulum bundle, and <strong>for</strong>nix may be vulnerable to the effects of<br />

early stress. Dim<strong>in</strong>ished fiber <strong>in</strong>tegrity, aberrant cross<strong>in</strong>g patterns,<br />

alterations <strong>in</strong> axonal diameter, or extent of myel<strong>in</strong>ation<br />

along portions of these pathways may underlie some of the<br />

psychiatric (5) and neurocognitive (43) consequences of childhood<br />

abuse. Although this is a prelim<strong>in</strong>ary study of modest size,<br />

we characterized young adults who to the best of our knowledge<br />

only suffered from parental verbal abuse. Results of this study<br />

may have public health implications, rais<strong>in</strong>g the possibility that<br />

parental criticism, condemnation, and ridicule can exert deleterious<br />

effects on the develop<strong>in</strong>g bra<strong>in</strong>.<br />

This work was supported, <strong>in</strong> part, by National Institute of<br />

Mental Health RO1 Grants MH53636 and MH-66222, and<br />

National Institute of Drug Abuse RO1 Grants DA-016934 and<br />

DA-017846 to MHT.<br />

We thank Ms. Cynthia E. McGreenery and Daniel Webster R.N.,<br />

M.S., C.S., <strong>for</strong> recruitment and <strong>in</strong>terview<strong>in</strong>g of subjects; Carryl P.<br />

Navalta, Ph.D., Kather<strong>in</strong>e Flag, Ph.D., and Keren Rabi, M.A. <strong>for</strong><br />

neuropsychological test<strong>in</strong>g; and Yi-Sh<strong>in</strong> Sheu <strong>for</strong> data management<br />

and file conversion. We also thank the anonymous reviewers <strong>for</strong><br />

suggestions that improved the quality and clarity of this report.<br />

None of the authors report any biomedical f<strong>in</strong>ancial <strong>in</strong>terests<br />

or potential conflicts of <strong>in</strong>terest relevant to the subject matter of<br />

this study.<br />

Supplementary material cited <strong>in</strong> this article is available<br />

onl<strong>in</strong>e.<br />

1. Caspi A, McClay J, Moffitt TE, Mill J, Mart<strong>in</strong> J, Craig IW, et al. (2002): Role of<br />

genotype <strong>in</strong> the cycle of violence <strong>in</strong> maltreated children. Science 297:<br />

851–854.<br />

2. Caspi A, Sugden K, Moffitt TE, Taylor A, Craig IW, Harr<strong>in</strong>gton H, et al.<br />

(2003): Influence of life stress on depression: Moderation by a polymorphism<br />

<strong>in</strong> the 5-HTT gene. Science 301:386–389.<br />

3. Teicher MH, Tomoda A, Andersen SL (2006): Neurobiological consequences<br />

of early stress and childhood maltreatment: Are results from<br />

human and animal studies comparable? Ann N Y Acad Sci 1071:313–323.<br />

4. Bernste<strong>in</strong> DP, Ahluvalia T, Pogge D, Handelsman L (1997): Validity of the<br />

Childhood Trauma Questionnaire <strong>in</strong> an adolescent psychiatric population.<br />

J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 36:340–348.<br />

5. Teicher MH, Samson JA, Polcari A, McGreenery CE (2006): Sticks, stones,<br />

and hurtful words: Relative effects of various <strong>for</strong>ms of childhood maltreatment.<br />

Am J Psychiatry 163:993–1000.<br />

6. Mann<strong>in</strong>g C, Cheers B (1995): Child abuse notification <strong>in</strong> a country town.<br />

Child Abuse Negl 19:387–397.<br />

7. Saulsbury FT, Campbell RE (1985): Evaluation of child abuse report<strong>in</strong>g<br />

by physicians. Am J Dis Child 139:393–395.<br />

8. De Bellis MD, Keshavan MS, Shifflett H, Iyengar S, Beers SR, Hall J, et al.<br />

(2002): Bra<strong>in</strong> structures <strong>in</strong> pediatric maltreatment-related posttraumatic<br />

stress disorder: A sociodemographically matched study. Biol Psychiatry<br />

52:1066–1078.<br />

9. De Bellis MD, Keshavan MS, Clark DB, Casey BJ, Giedd JN, Bor<strong>in</strong>g AM, et<br />

al. (1999): Developmental traumatology. Part II: Bra<strong>in</strong> development. Biol<br />

Psychiatry 45:1271–1284.<br />

10. Teicher MH, Dumont NL, Ito Y, Vaituzis C, Giedd JN, Andersen SL (2004):<br />

Childhood neglect is associated with reduced corpus callosum area. Biol<br />

Psychiatry 56:80–85.<br />

11. Teicher MH, Ito Y, Glod CA, Andersen SL, Dumont N, Ackerman E (1997):<br />

<strong>Prelim<strong>in</strong>ary</strong> evidence <strong>for</strong> abnormal cortical development <strong>in</strong> physically<br />

and sexually abused children us<strong>in</strong>g EEG coherence and MRI. Ann N Y<br />

Acad Sci 821:160–175.<br />

12. Andersen SL, Tomada A, V<strong>in</strong>cow ES, Valente E, Polcari A, Teicher MH (<strong>in</strong><br />

press): <strong>Prelim<strong>in</strong>ary</strong> evidence <strong>for</strong> sensitive periods <strong>in</strong> the effect of childhood<br />

sexual abuse on regional bra<strong>in</strong> development. J Neuropsychiatry<br />

Cl<strong>in</strong> Neurosci.<br />

13. Catani M (2006): Diffusion tensor magnetic resonance imag<strong>in</strong>g tractography<br />

<strong>in</strong> cognitive disorders. Curr Op<strong>in</strong> Neurol 19:599–606.<br />

14. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW (1997): Structured Cl<strong>in</strong>ical<br />

Interview <strong>for</strong> DSM-IV Axis I Disorders-Cl<strong>in</strong>ician Version (SCID-CV). Wash<strong>in</strong>gton,<br />

DC: American Psychiatric Press.<br />

15. Herman JL, Perry JC, van der Kolk BA (1989): Traumatic Antecedents<br />

Interview. Boston: The Trauma Center.<br />

16. Wechsler D (1997): Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-III. New York: The<br />

Psychological Corporation.<br />

17. Bernste<strong>in</strong> EM, Putnam FW (1986): Development, reliability and validity<br />

of a dissociation scale. J Nerv Ment Dis 174:727–735.<br />

18. Teicher MH, Glod CA, Surrey J, Swett C Jr (1993): Early childhood abuse<br />

and limbic system rat<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong> adult psychiatric outpatients. J Neuropsychiatry<br />

Cl<strong>in</strong> Neurosci 5:301–306.<br />

19. Kellner R (1987): A symptom questionnaire. J Cl<strong>in</strong> Psychiatry 48:268–273.<br />

20. Reese TG, Heid O, Weisskoff RM, Wedeen VJ (2003): Reduction of eddycurrent-<strong>in</strong>duced<br />

distortion <strong>in</strong> diffusion MRI us<strong>in</strong>g a twice-refocused sp<strong>in</strong><br />

echo. Magn Reson Med 49:177–182.<br />

21. Smith SM, Jenk<strong>in</strong>son M, Johansen-Berg H, Rueckert D, Nichols TE,<br />

Mackay CE, et al. (2006): <strong>Tract</strong>-based spatial statistics: Voxelwise analysis<br />

of multi-subject diffusion data. Neuroimage 31:1487–1505.<br />

22. Duncan GL, Magnuson KA (2003): Off with Holl<strong>in</strong>gshead: Socioeconomic<br />

Resources, Parent<strong>in</strong>g, and Child Development. In: Bornste<strong>in</strong> MH,<br />

Bradley RH, editors. Socioeconomic Status, Parent<strong>in</strong>g, and Child Development.<br />

Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum, 83–106.<br />

23. Sohr-Preston SL, Scaramella LV (2006): Implications of tim<strong>in</strong>g of maternal<br />

depressive symptoms <strong>for</strong> early cognitive and language development.<br />

Cl<strong>in</strong> Child Fam Psychol Rev 9:65–83.<br />

24. Koenen KC, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Taylor A, Purcell S (2003): Domestic<br />

violence is associated with environmental suppression of IQ <strong>in</strong> young<br />

children. Dev Psychopathol 15:297–311.<br />

25. Delaney-Black V, Cov<strong>in</strong>gton C, Ondersma SJ, Nordstrom-Klee B, Templ<strong>in</strong><br />

T, Ager J, et al. (2002): Violence exposure, trauma, and IQ and/or read<strong>in</strong>g<br />

deficits among urban children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 156:280–285.<br />

26. Russo R (2003): Statistics <strong>for</strong> the Behavioral Sciences: An Introduction.<br />

Philadelphia: Psychology Press.<br />

27. Behrens TE, Woolrich MW, Jenk<strong>in</strong>son M, Johansen-Berg H, Nunes RG,<br />

Clare S, et al. (2003): Characterization and propagation of uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty <strong>in</strong><br />

diffusion-weighted MR imag<strong>in</strong>g. Magn Reson Med 50:1077–1088.<br />

28. Vernooij MW, Smits M, Wielopolski PA, Houston GC, Krest<strong>in</strong> GP, van der<br />

Lugt A (2007): Fiber density asymmetry of the arcuate fasciculus <strong>in</strong><br />

relation to functional hemispheric language lateralization <strong>in</strong> both rightand<br />

left-handed healthy subjects: A comb<strong>in</strong>ed fMRI and DTI study.<br />

Neuroimage 35:1064–1076.<br />

29. Concha L, Gross DW, Beaulieu C (2005): Diffusion tensor tractography of<br />

the limbic system. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 26:2267–2274.<br />

30. Makris N, Kennedy DN, McInerney S, Sorensen AG, Wang R, Cav<strong>in</strong>ess VS<br />

Jr, et al. (2005): Segmentation of subcomponents with<strong>in</strong> the superior<br />

longitud<strong>in</strong>al fascicle <strong>in</strong> humans: A quantitative, <strong>in</strong> vivo, DT-MRI study.<br />

Cereb Cortex 15:854–869.<br />

31. Breier JI, Hasan KM, Zhang W, Men D, Papanicolaou AC (2008): Language<br />

dysfunction after stroke and damage to white matter tracts<br />

evaluated us<strong>in</strong>g diffusion tensor imag<strong>in</strong>g. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 29:<br />

483–487.<br />

32. Kim SJ, Jeong DU, Sim ME, Bae SC, Chung A, Kim MJ, et al. (2006):<br />

Asymmetrically altered <strong>in</strong>tegrity of c<strong>in</strong>gulum bundle <strong>in</strong> posttraumatic<br />

stress disorder. Neuropsychobiology 54:120–125.<br />

33. Spiers PA, Schomer DL, Blume HW, Mesulam MM (1985): Temporolimbic<br />

epilepsy and behavior. In: Mesulam MM, editor. Pr<strong>in</strong>ciples of Behavioral<br />

Neurology. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis, 289–326.<br />

34. Degroot A, Treit D (2004): Anxiety is functionally segregated with<strong>in</strong> the<br />

septo-hippocampal system. Bra<strong>in</strong> Res 1001:60–71.<br />

35. Moore RY, Halaris AE (1975): Hippocampal <strong>in</strong>nervation by seroton<strong>in</strong><br />

neurons of the midbra<strong>in</strong> raphe <strong>in</strong> the rat. J Comp Neurol 164:171–183.<br />

36. Patel TD, Azmitia EC, Zhou FC (1996): Increased 5-HT1A receptor immunoreactivity<br />

<strong>in</strong> the rat hippocampus follow<strong>in</strong>g 5,7-dihydroxytryptam<strong>in</strong>e<br />

www.sobp.org/journal

234 BIOL PSYCHIATRY 2009;65:227–234 J. Choi et al.<br />

lesions <strong>in</strong> the c<strong>in</strong>gulum bundle and fimbria-<strong>for</strong>nix. Behav Bra<strong>in</strong> Res<br />

73:319–323.<br />

37. Jones DK, Catani M, Pierpaoli C, Reeves SJ, Shergill SS, O’Sullivan M, et al.<br />

(2006): Age effects on diffusion tensor magnetic resonance imag<strong>in</strong>g<br />

tractography measures of frontal cortex connections <strong>in</strong> schizophrenia.<br />

Hum Bra<strong>in</strong> Mapp 27:230–238.<br />

38. Shergill SS, Kanaan RA, Chitnis XA, O’Daly O, Jones DK, Frangou S, et al.<br />

(2007): A diffusion tensor imag<strong>in</strong>g study of fasciculi <strong>in</strong> schizophrenia.<br />

Am J Psychiatry 164:467–473.<br />

39. Eluvath<strong>in</strong>gal TJ, Hasan KM, Kramer L, Fletcher JM, Ew<strong>in</strong>g-Cobbs L (2007):<br />

Quantitative diffusion tensor tractography of association and projection<br />

fibers <strong>in</strong> normally develop<strong>in</strong>g children and adolescents. Cereb Cortex<br />

17:2760–2768.<br />

www.sobp.org/journal<br />

40. Schmahmann JD, Pandya DN, Wang R, Dai G, D’Arceuil HE, de Crespigny<br />

AJ, et al. (2007): Association fibre pathways of the bra<strong>in</strong>: Parallel observations<br />

from diffusion spectrum imag<strong>in</strong>g and autoradiography. Bra<strong>in</strong><br />

130:630–653.<br />

41. Keshavan MS, Diwadkar VA, DeBellis M, Dick E, Kotwal R, Rosenberg DR,<br />

et al. (2002): Development of the corpus callosum <strong>in</strong> childhood, adolescence<br />

and early adulthood. Life Sci 70:1909–1922.<br />

42. Juraska JM, Kopcik JR (1988): Sex and environmental <strong>in</strong>fluences on the<br />

size and ultrastructure of the rat corpus callosum. Bra<strong>in</strong> Res 450:1–8.<br />

43. Navalta CP, Polcari A, Webster DM, Boghossian A, Teicher MH (2006):<br />

Effects of childhood sexual abuse on neuropsychological and cognitive<br />

functiofunction <strong>in</strong> college women. J Neuropsychiatry Cl<strong>in</strong> Neurosci 18:<br />

45–53.