Applying new science theories in leadership development ... - Emerald

Applying new science theories in leadership development ... - Emerald

Applying new science theories in leadership development ... - Emerald

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Apply<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>new</strong> <strong>science</strong> <strong>theories</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>leadership</strong> <strong>development</strong><br />

activities<br />

Stephen A. Stumpf<br />

The University of Tampa, Tampa, Florida, USA<br />

If one assumes that the breakthroughs <strong>in</strong> the biological, chemical, and physical<br />

<strong>science</strong>s over the last four-score years have added <strong>new</strong> layers of mean<strong>in</strong>g to our<br />

world, then it is worthwhile to ask “Do <strong>new</strong> <strong>science</strong> discoveries have<br />

implications for <strong>leadership</strong> <strong>in</strong> work organizations?” Certa<strong>in</strong>ly, the natural<br />

<strong>science</strong> discoveries of Newton and others <strong>in</strong> past centuries affected our views<br />

of organizations. The organizational form we call a bureaucracy reflects our<br />

knowledge of structural mechanics – a bureaucracy is <strong>in</strong>tended to be a set of<br />

parts (people) with functions (roles) that follow accepted scientific pr<strong>in</strong>ciples<br />

(policies). This mach<strong>in</strong>e metaphor for organizations rema<strong>in</strong>s pervasive as we<br />

cont<strong>in</strong>ue to try to determ<strong>in</strong>e, predict, measure, and evaluate all sorts of<br />

organizational phenomena (i.e. a Newtonian cause and effect view of<br />

organizational behaviour). Recently, Wheatley[1] suggested several<br />

implications of <strong>new</strong> <strong>science</strong> <strong>theories</strong> that can be useful <strong>in</strong> understand<strong>in</strong>g and<br />

improv<strong>in</strong>g how organizations are designed, perceived, and function. Unless<br />

these implications are developed and translated <strong>in</strong>to the practices of leaders,<br />

the utility of <strong>new</strong> <strong>science</strong> discoveries will be m<strong>in</strong>imal.<br />

A group of colleagues at New York University (NYU) unknow<strong>in</strong>gly created<br />

a virtual organization <strong>in</strong> 1980 based on today’s <strong>new</strong> <strong>science</strong> premisses[2]. True<br />

to the <strong>new</strong> <strong>science</strong> paradigms, we neither k<strong>new</strong> that we were a virtual<br />

organization nor that we shared <strong>new</strong> <strong>science</strong> premisses until we observed<br />

ourselves over time. Our name at found<strong>in</strong>g, the NYU Management Simulation<br />

Projects Group, and the creation of the not-for-profit MSP Institute, Inc. several<br />

years later, reflects the content of what we are about – design<strong>in</strong>g and us<strong>in</strong>g<br />

management simulations to help others learn how to be more effective <strong>in</strong> work<br />

organizations.<br />

The found<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> 1993 of the Center for Leadership at The University of<br />

Tampa provided the opportunity to reflect on our activities. Writ<strong>in</strong>gs on the<br />

applications of <strong>new</strong> <strong>science</strong> <strong>theories</strong> to the organizational <strong>science</strong>s capture<br />

much of our evolution. Our <strong>leadership</strong> <strong>development</strong> approach and activities are<br />

consistent with <strong>new</strong> <strong>science</strong> implications for organizational learn<strong>in</strong>g and<br />

effectiveness <strong>in</strong> environments that are complex and turbulent.<br />

The thoughtful comments and ideas of Hrach Bedrosian, Andy Flem<strong>in</strong>g, and Susan He<strong>in</strong>buch are<br />

greatly appreciated.<br />

<strong>Apply<strong>in</strong>g</strong><br />

<strong>new</strong> <strong>science</strong><br />

<strong>theories</strong><br />

39<br />

Journal of Management<br />

Development, Vol. 14 No. 5, 1995,<br />

pp. 39-49. © MCB University Press,<br />

0262-1711

Journal of<br />

Management<br />

Development<br />

14,5<br />

40<br />

New <strong>science</strong> implications for organizational learn<strong>in</strong>g and<br />

effectiveness<br />

To sum up <strong>new</strong> <strong>science</strong> <strong>in</strong> a few paragraphs would be difficult, if not impossible.<br />

Each attempt to describe <strong>new</strong> <strong>science</strong> is different from the previous one (which,<br />

of course, is exactly what <strong>new</strong> <strong>science</strong> would suggest as no idea, person, or<br />

th<strong>in</strong>g can be def<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong>dependently from others). Yet, the written word requires<br />

one to commit to a po<strong>in</strong>t of view to an unknowable audience. These paragraphs<br />

are “a stake <strong>in</strong> the ground” as a po<strong>in</strong>t of departure.<br />

Much of what we observe and do <strong>in</strong> organizations can be partially<br />

understood and conducted through the application of pre-<strong>new</strong> <strong>science</strong><br />

management <strong>theories</strong> (I hesitate to use the word “old”). What occurs <strong>in</strong><br />

organizations often fits a Newtonian perspective of the world, one <strong>in</strong> which:<br />

● organizations are designed to have many mach<strong>in</strong>e-like characteristics<br />

and functions;<br />

● most events and <strong>in</strong>teractions are predictable and measurable;<br />

● many of our expectations of regularity are met;<br />

● there exist well-def<strong>in</strong>ed variables, boundaries, and cause-effect<br />

relationships; and<br />

● there are pr<strong>in</strong>ciples, policies, and rules to guide behaviour because we<br />

know the better ways to do th<strong>in</strong>gs, if not the best ways.<br />

We see problems, we isolate them, and we solve them. When our solutions fail<br />

to take <strong>in</strong>to account the <strong>in</strong>terconnectedness of events, we may make matters<br />

worse. If this occurs, we tend to def<strong>in</strong>e the situation as a <strong>new</strong> problem, ignor<strong>in</strong>g<br />

or not see<strong>in</strong>g the l<strong>in</strong>ks between the <strong>in</strong>itial problem, our solution, and the <strong>new</strong><br />

problem. We prefer not to admit that chaos exists <strong>in</strong> our <strong>leadership</strong> doma<strong>in</strong> –<br />

complexity that looks like chaos just needs a bit more study. Once we have a<br />

better analytic or determ<strong>in</strong>istic models and measures, the illusion of chaos will<br />

be gone.<br />

As one elaborates the mach<strong>in</strong>e metaphor, some analogies become less<br />

generalizable. Exceptions emerge. New <strong>science</strong> concepts can provide<br />

frameworks that help us understand behaviour <strong>in</strong> organizations beyond our<br />

current understand<strong>in</strong>gs derived from earlier scientific perspectives. Three <strong>new</strong><br />

<strong>science</strong> <strong>theories</strong> are mentioned. These are followed by a discussion of several<br />

<strong>leadership</strong> approaches and activities that are consistent with Wheatley’s[1]<br />

implications of <strong>new</strong> <strong>science</strong> concepts for the organizational <strong>science</strong>s.<br />

Quantum mechanics<br />

Probably the most profound premiss of quantum mechanics is that there are no<br />

prefixed, def<strong>in</strong>itely describable th<strong>in</strong>gs. Th<strong>in</strong>gs only exist <strong>in</strong> relationship to other<br />

th<strong>in</strong>gs. As we look around us, this premiss seems implausible. Yet, <strong>in</strong> the world<br />

of organizational behaviour, we are <strong>in</strong>terested <strong>in</strong> “th<strong>in</strong>gs” that are not th<strong>in</strong>gs at<br />

all. Our <strong>in</strong>terests are <strong>in</strong> the behaviours, thoughts, emotions, values, attitudes,<br />

images of the future, dreams, and memories of diverse, <strong>in</strong>terconnected groups

of people we call the organization, its suppliers, customers, shareholders, and<br />

other significant stakeholders. The actual behaviours observed may be<br />

tangible, but the cause of the behaviour and its predictability are <strong>in</strong>tangibles<br />

and not completely known. At best, a particular behaviour is probabilistic, not<br />

determ<strong>in</strong>istic.<br />

Quantum mechanics suggests that behaviours, just as thoughts, are<br />

<strong>in</strong>determ<strong>in</strong>able <strong>in</strong> isolation from their context, and their contexts (past and<br />

present) are beyond complete description (i.e. they are <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>ite). Moreover, as<br />

behaviours exist only <strong>in</strong> relationship to other behaviours, the process of<br />

observ<strong>in</strong>g them or shar<strong>in</strong>g ideas <strong>in</strong>troduces a <strong>new</strong> relationship – hence the<br />

observed behaviour or shared idea is different from its unobserved counterpart.<br />

The <strong>leadership</strong> <strong>development</strong> implications of quantum mechanics can be quite<br />

practical. First, it may be fruitless to approach <strong>leadership</strong> <strong>development</strong> <strong>in</strong> a<br />

determ<strong>in</strong>istic manner by assum<strong>in</strong>g that if the leader does x, y will occur. The<br />

notion that a leader should have specific responses to specific situations as<br />

articulated <strong>in</strong> many models of <strong>leadership</strong> should be suspect. What is needed is<br />

a heuristic framework for <strong>leadership</strong> – one <strong>in</strong> which discover<strong>in</strong>g is the<br />

underly<strong>in</strong>g dynamic process, not the discovery per se. Leadership would no<br />

longer be def<strong>in</strong>ed as <strong>in</strong>fluenc<strong>in</strong>g others to accomplish specific goals, but as a<br />

process <strong>in</strong> which it is more valuable and important to explore and move<br />

towards someth<strong>in</strong>g than to accomplish it. Leadership <strong>in</strong>volves creat<strong>in</strong>g and<br />

susta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g fields of energy <strong>in</strong> which relationships grow, develop, and become<br />

<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly purposeful, dynamic, and effective. Excitement and energy come<br />

from anticipations and wonderment about the next round of events.<br />

Organizations will cont<strong>in</strong>ue, no doubt, to measure th<strong>in</strong>gs that have passed. The<br />

leaders should be guided by the excitement of the future more than by past<br />

accomplishments.<br />

A second implication is that discover<strong>in</strong>g <strong>leadership</strong> cannot be separated from<br />

efforts to behave as a leader. One must be an active observer and player, <strong>in</strong><br />

active partnership with the organization and its environments, to learn much<br />

from events or experiences. Study<strong>in</strong>g <strong>leadership</strong> without experienc<strong>in</strong>g it is an<br />

<strong>in</strong>efficient way to learn, if such learn<strong>in</strong>g is possible. The ability to “live”<br />

experiences and discover what is mean<strong>in</strong>gful <strong>in</strong> them is a necessary condition<br />

for <strong>leadership</strong> <strong>development</strong>.<br />

A third implication relates to the challenge of def<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g “reality” <strong>in</strong> any open<br />

system. Perception is reality for each <strong>in</strong>dividual, and there is no perception <strong>in</strong><br />

isolation. Perception requires someth<strong>in</strong>g to be perceived. Hence, reality <strong>in</strong> work<br />

organizations is likely to be whatever sense people make of their observations<br />

and <strong>in</strong>teractions. This suggests that our measures of <strong>leadership</strong> behaviours<br />

must <strong>in</strong>clude the perceptions of all those <strong>in</strong> the collective relationship. How a<br />

manager relates to one direct report is dependent on:<br />

● how he/she relates to other direct reports,<br />

● how these direct reports relate to the manager, and<br />

● how the manager relates with her or his manager.<br />

<strong>Apply<strong>in</strong>g</strong><br />

<strong>new</strong> <strong>science</strong><br />

<strong>theories</strong><br />

41

Journal of<br />

Management<br />

Development<br />

14,5<br />

42<br />

Self-organiz<strong>in</strong>g systems<br />

The Second Law of Thermodynamics states that entropy applies <strong>in</strong> all isolated<br />

and closed systems. Entropy, a process of cont<strong>in</strong>ual dis<strong>in</strong>tegration to a state of<br />

randomness, is a predictable outcome of any system <strong>in</strong> the absence of <strong>new</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>puts. Open systems overcome entropy by <strong>in</strong>teract<strong>in</strong>g with the environment –<br />

tak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> needed resources.<br />

Self-organiz<strong>in</strong>g system theory posits that open systems use disorder to create<br />

possibilities for growth. Through both resilience and self-reference, selforganiz<strong>in</strong>g<br />

systems are capable of ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g an identity while chang<strong>in</strong>g<br />

form. They have both autonomy and control. Each form that is created works<br />

for the moment. If <strong>new</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation supports the form, it persists. If <strong>new</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>formation threatens the form, the system looks for ways to accommodate the<br />

<strong>in</strong>formation by mak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>cremental changes that are consistent with much of<br />

its past but do not unnecessarily deny the <strong>new</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation or a <strong>new</strong> future.<br />

This “roll<strong>in</strong>g equilibrium” or adjustment is more than a reaction to an action <strong>in</strong><br />

the Newtonian sense because the reaction is not predictable.<br />

What happens if the autonomy with<strong>in</strong> such systems is removed (i.e. if they<br />

are externally controlled by the organization)? Self-organiz<strong>in</strong>g system theory<br />

suggests that <strong>in</strong> such situations the system will fail to adjust to the environment<br />

<strong>in</strong> a timely manner as it must obta<strong>in</strong> approval from parts of the organization<br />

that have not experienced the environment <strong>in</strong> the same way. Autonomy is<br />

central to the system’s evolution. This raises the question, “How does an<br />

organization control a self-organiz<strong>in</strong>g system?” The answer may be that it does<br />

not. The self-organiz<strong>in</strong>g system operates with<strong>in</strong> a relatively stable, more global<br />

structure. Changes with<strong>in</strong> the local structure tend to have only a m<strong>in</strong>or effect on<br />

the global structure. The stability of the global structure stems from its creation<br />

over time as a result of the culture, vision, and values shared by the majority of<br />

organizational members and key stakeholders.<br />

The <strong>leadership</strong> <strong>development</strong> implications of self-organiz<strong>in</strong>g system theory<br />

are found <strong>in</strong> the provid<strong>in</strong>g of direction and control. First, disequilibrium and<br />

disorder are not viewed as negative attributes of such systems. Some degree of<br />

each is necessary to provide the system with opportunities to adjust to <strong>new</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>formation. As adjustments are made, the self-organiz<strong>in</strong>g system learns how<br />

to accommodate to its environment. Leadership efforts that try to elim<strong>in</strong>ate<br />

disorder and control behaviour will destroy the system’s ability to self-organize.<br />

Novelty of response is often necessary. Without <strong>new</strong> stimuli, which often arises<br />

out of discontentedness, people lapse <strong>in</strong>to dull habit. In so do<strong>in</strong>g, the likelihood<br />

of maladaptive behaviour <strong>in</strong>creases ow<strong>in</strong>g to differences <strong>in</strong> each actor’s<br />

perceived reality of the situation.<br />

A second implication has to do with the self-organiz<strong>in</strong>g system’s ability to<br />

develop <strong>in</strong>sights. Insights are <strong>new</strong> formulations of reality based on different<br />

connections of previously experienced <strong>in</strong>formation. They br<strong>in</strong>g personal<br />

enjoyment and build the m<strong>in</strong>d’s capacity to <strong>in</strong>teract more effectively with the<br />

environment. The <strong>development</strong> of <strong>in</strong>sights requires one to look <strong>in</strong>ward to make<br />

connections among previously unrelated ideas, people, events, or situations –

creat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>new</strong> mean<strong>in</strong>g out of these connections. The greater the degree of<br />

control imposed by an external system, the fewer the <strong>in</strong>sights developed as <strong>new</strong><br />

formulations are not encouraged or tolerated.<br />

Chaos theory<br />

Chaos may not be chaos at all. At some level, or from some perspective, order<br />

does exist for some period of time. What appears to be chaos, if left alone, will<br />

conform to unspecified boundaries. Once the boundaries have emerged, the<br />

system no longer experiences the fluctuations, disturbances, or imbalances<br />

previously perceived to be chaos. In fact, these variances are often a primary<br />

source of creativity with<strong>in</strong> the system.<br />

Help<strong>in</strong>g people to learn from and accept the perception of chaos is a<br />

significant challenge for <strong>leadership</strong> <strong>development</strong> activities. How does one<br />

develop the patience and capacity to absorb variances without be<strong>in</strong>g tempted to<br />

control or elim<strong>in</strong>ate them? The answer may be <strong>in</strong> look<strong>in</strong>g for order amidst<br />

disorder, and giv<strong>in</strong>g up the notion of control. One can always f<strong>in</strong>d order <strong>in</strong> a<br />

system, if only an order of process rather than form. All th<strong>in</strong>gs and events have<br />

order from some perspective for short periods of time. See<strong>in</strong>g the order may not<br />

be as crucial as know<strong>in</strong>g that it is there. Children struggle with this as they<br />

learn to accept the reality that a parent not present does not mean that the<br />

parent does not exist. They beg<strong>in</strong> a process of develop<strong>in</strong>g faith – beliefs about<br />

events or th<strong>in</strong>gs that are beyond comprehension.<br />

Leadership <strong>development</strong> concepts, models, and activities<br />

The University of Tampa Center for Leadership designs and delivers <strong>leadership</strong><br />

<strong>development</strong> programmes for bus<strong>in</strong>ess organizations and its undergraduate<br />

and MBA student populations. One such programme is a prototype of the<br />

<strong>leadership</strong> <strong>development</strong> programmes offered. Initially designed for Aetna Life<br />

and Casualty, it is frequently offered by the Life Office Management Association<br />

(LOMA is a life <strong>in</strong>surance <strong>in</strong>dustry trade association located <strong>in</strong> Atlanta, GA).<br />

Other Center for Leadership programmes which have a comparable focus are<br />

conducted as a Leadership Lab required of undergraduate and MBA students,<br />

and for several dozen bus<strong>in</strong>esses and not-for-profit organizations around the<br />

world.<br />

The LOMA Middle Management Workshop on Leadership is a five-day<br />

programme targeted at middle level managers throughout the <strong>in</strong>surance<br />

<strong>in</strong>dustry who are viewed by their organizations as hav<strong>in</strong>g senior management<br />

potential. The programme starts with discussions of “What is go<strong>in</strong>g on <strong>in</strong> your<br />

environment that is affect<strong>in</strong>g you today?” and “What is <strong>leadership</strong>?” After<br />

shar<strong>in</strong>g several of the current views of effective <strong>leadership</strong> practices, we move<br />

from the traditional mechanistic view of organizations and control to human<br />

behaviour perspectives consistent with organizational <strong>science</strong> implications of<br />

the <strong>new</strong> <strong>science</strong> paradigms.<br />

The role of the workshop facilitator is a <strong>leadership</strong> activity. The facilitator<br />

strives to create fields of energy <strong>in</strong> which participants develop <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly<br />

<strong>Apply<strong>in</strong>g</strong><br />

<strong>new</strong> <strong>science</strong><br />

<strong>theories</strong><br />

43

Journal of<br />

Management<br />

Development<br />

14,5<br />

44<br />

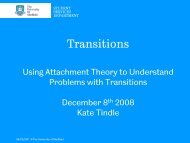

Figure 1.<br />

The W-cubed model<br />

purposeful, dynamic, and effective relationships which serve to generate<br />

<strong>in</strong>dividual <strong>in</strong>sights. It is these participant <strong>in</strong>sights, as they are able to reflect the<br />

shared realities of others <strong>in</strong> their workplace, that led them and their units to<br />

accomplish significant bus<strong>in</strong>ess results.<br />

Heuristic models to guide leader behaviour<br />

For over a decade <strong>leadership</strong> <strong>development</strong> models have evolved that have<br />

<strong>in</strong>troduced and discussed the processes of diagnosis and discovery. Three<br />

books capture many of the more generalizable and useful models for learn<strong>in</strong>g<br />

about <strong>leadership</strong> and improv<strong>in</strong>g one’s <strong>leadership</strong> efforts[3-5].<br />

One model, labelled W-cubed, asks three questions: What do we want?, What<br />

do they want?, and What can we do? (See Figure 1.) To use the model, one must<br />

first specify the issue or situation to be diagnosed. The model then directs the<br />

user to determ<strong>in</strong>e who the “we” are, what it is that “we” really want <strong>in</strong> this<br />

situation, who the different “theys” are, and what it is we perceive them to want.<br />

Given this diagnosis, we return to the model to explore what it is the “we” can<br />

do – now and <strong>in</strong> the future.<br />

The W-cubed model guides its user through an <strong>in</strong>teractive process of<br />

discover<strong>in</strong>g possible actions that simultaneously satisfy what it is that “We<br />

want,” “What the different theys want,” and “What it is that we can do” to<br />

satisfy both our wants and their wants. This “sweet spot” is noted by the<br />

shaded area <strong>in</strong> Figure 1. In practice, users of W-cubed f<strong>in</strong>d that they are unable<br />

to identify actions that easily satisfy the three elements of the model<br />

simultaneously. The existence of many “theys” who often have different wants<br />

leads to an ongo<strong>in</strong>g process of try<strong>in</strong>g to satisfy enough of their wants (along<br />

with your wants) for the present to keep the relationship healthy. The<br />

relationship grows over time if more and more of each party’s wants are be<strong>in</strong>g<br />

satisfied; it degenerates if wants are not be<strong>in</strong>g satisfied. The former leads to<br />

self-organiz<strong>in</strong>g system relationships, the latter to entropy.<br />

The W-cubed model and other heuristic tools used <strong>in</strong> Center for Leadership<br />

programmes are fully described elsewhere[3,4]. Without tak<strong>in</strong>g the space to<br />

What do<br />

we want?<br />

w 3<br />

What can we do?<br />

What do<br />

they want?

discuss them separately, some generalizations are useful. Each heuristic model<br />

has several characteristics which are consistent with the organizational<br />

implications of <strong>new</strong> <strong>science</strong> <strong>theories</strong>. Each model:<br />

● <strong>in</strong>volves and supports an ongo<strong>in</strong>g, iterative thought process that can<br />

become self-organiz<strong>in</strong>g with<strong>in</strong> the frame of the model;<br />

● is not a set of judgments or conclusions (i.e. the models do not tell one<br />

what to do or the “correct” action to take, they are not determ<strong>in</strong>istic);<br />

● <strong>in</strong>corporates multiple perspectives and encourages one to obta<strong>in</strong> such<br />

perspectives;<br />

● has general applicability to a wide array of organizational situations –<br />

the models are not specific to a function, product, process, or <strong>in</strong>dustry;<br />

and<br />

● acknowledges and supports a cont<strong>in</strong>ual change and cont<strong>in</strong>uous<br />

improvement approach to <strong>leadership</strong> and accepts the often perceived<br />

chaos <strong>in</strong> and around organizations.<br />

Our use of these models <strong>in</strong> the LOMA Middle Management Workshop leverages<br />

the attributes of the models. For example, we ask participants to br<strong>in</strong>g with<br />

them a work issue or situation that they would like to exam<strong>in</strong>e while at the<br />

programme. After the models are described by the staff, participants apply<br />

them to a video case – first <strong>in</strong>dividually, then <strong>in</strong> small groups, and f<strong>in</strong>ally,<br />

collectively. Participants are then asked to apply the models <strong>in</strong> a live situation –<br />

one that is part of a behavioural simulation[6]. Although the stimulus<br />

(simulation) is artificial, the use of the models becomes both real and live for<br />

participants as they use the models <strong>in</strong> an actual <strong>leadership</strong> situation. After<br />

receiv<strong>in</strong>g feedback on each model’s use from each other and the tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g staff,<br />

trio groups are formed to address the situations brought by each participant.<br />

The models are first applied <strong>in</strong>dividually, then shared with<strong>in</strong> a trio group, and<br />

f<strong>in</strong>ally explored by the trio group collectively.<br />

The result after three rounds of model application with<strong>in</strong> each trio is a unique<br />

set of ideas to be explored and tried by each participant on return to their<br />

respective organizations. One of the learn<strong>in</strong>gs is that the more diverse the<br />

backgrounds of the trio participants, the more creative and varied are the<br />

solutions discussed. Trio groups act like self-organiz<strong>in</strong>g systems. The key to a<br />

trio’s success is whether or not they put energy <strong>in</strong>to their system; if they do, the<br />

system leads to higher orders of ideas.<br />

The <strong>leadership</strong> <strong>development</strong> processes used reflect the <strong>new</strong> <strong>science</strong> <strong>theories</strong>.<br />

There are no prefixed, def<strong>in</strong>itely describable outcomes to each activity. The<br />

collective wisdom of the groups is used to identify desirable outcomes for each<br />

activity. While there is noticeable commonality among desirable outcomes<br />

across programmes, much is unique to the actual process used, participant<br />

backgrounds, and dynamics created with<strong>in</strong> the groups. Our focus is on<br />

understand<strong>in</strong>g the flow of relationships and use of discovery models, not<br />

normative <strong>leadership</strong> practices.<br />

<strong>Apply<strong>in</strong>g</strong><br />

<strong>new</strong> <strong>science</strong><br />

<strong>theories</strong><br />

45

Journal of<br />

Management<br />

Development<br />

14,5<br />

46<br />

Assessment of <strong>leadership</strong> competence<br />

A second activity that is part of the LOMA Middle Management Workshop is<br />

the use of our multirater Leadership Inventory. The use of such <strong>in</strong>struments,<br />

sometimes called 360 degree assessments or rounded appraisal <strong>in</strong>struments,<br />

obta<strong>in</strong>s the <strong>in</strong>put of a participant’s manager(s), peers, direct reports, and self on<br />

a fixed set of <strong>leadership</strong> behaviours with ample space provided for open-ended<br />

comments. While the use of a fixed set of items implies a determ<strong>in</strong>istic approach<br />

to <strong>leadership</strong> skills, the process we use with the Leadership Inventory<br />

compensates for this one-best-way view of <strong>leadership</strong> skill.<br />

Such <strong>in</strong>struments traditionally consist of items that have been validated<br />

through job sampl<strong>in</strong>g and/or predictive validity studies (e.g. a sample item is<br />

“To what extent does he/she encourage co-operative problem solv<strong>in</strong>g?”). We<br />

used a job sampl<strong>in</strong>g approach. The use of multirater <strong>in</strong>struments typically<br />

<strong>in</strong>volves a participant receiv<strong>in</strong>g a package of <strong>in</strong>struments and <strong>in</strong>structions to:<br />

(a) perform a self appraisal, and (b) send copies of the <strong>in</strong>struments to his or her<br />

manager(s), peers, and direct reports. An attempt is usually made to collect the<br />

data <strong>in</strong> a confidential manner, e.g. completed forms are sent to an adm<strong>in</strong>istrator<br />

or the external supplier for computer scor<strong>in</strong>g. The feedback provided to each<br />

participant often consists of the means of each item’s multiple responses<br />

displayed as bar charts.<br />

We view such analysis and report<strong>in</strong>g of the results of a multirater <strong>in</strong>strument<br />

as unnecessarily mechanistic. If one peer perceives a participant’s performance<br />

as low, another as high, the report says medium. This is ak<strong>in</strong> to one peer<br />

perceiv<strong>in</strong>g a participant as “blue,” another as “yellow”, and the computer<br />

report<strong>in</strong>g that the participant is “green”. New <strong>science</strong> <strong>theories</strong> suggest that<br />

each rater’s perspective might be of greatest value if considered separately, with<br />

any synthesis be<strong>in</strong>g done by the participant directly (not a computer<br />

programmed to calculate an average).<br />

We accomplish this by hav<strong>in</strong>g participants perform the tally<strong>in</strong>g of the<br />

responses from their manager(s), peers, and direct reports themselves.<br />

Confidentiality, if important to a participant, can be ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed by the way <strong>in</strong><br />

which responses are returned (e.g., <strong>in</strong> non-identify<strong>in</strong>g envelopes). As<br />

participants tally their multirater feedback, we encourage them to reta<strong>in</strong> the<br />

perspective of the provider (e.g. manager, peer, direct report) and to look for any<br />

patterns with<strong>in</strong> the responses. Once their feedback is arrayed, <strong>in</strong>structions are<br />

provided such as:<br />

● Look over the pattern of responses to each item, item by item. What are<br />

these responses tell<strong>in</strong>g you? Is there an overarch<strong>in</strong>g story?<br />

● Which of the raters has had a greater opportunity to observe you with<br />

respect to each item? Should their feedback be thought about differently<br />

than those who have had little opportunity to observe?<br />

● Are some raters <strong>in</strong> a better position to provide you with feedback on<br />

some items?

● If different raters tend to agree, what does this mean to you? If they<br />

disagree <strong>in</strong> some ways, what might this mean?<br />

● Summarize your <strong>in</strong>terpretation of the pattern of responses <strong>in</strong> your own<br />

words. Plan on shar<strong>in</strong>g this <strong>in</strong>terpretation with the facilitator who will be<br />

observ<strong>in</strong>g you <strong>in</strong> the simulation which takes place tomorrow.<br />

Participants are asked to make sense out of their feedback <strong>in</strong> light of their<br />

knowledge of their jobs, the people who provided the <strong>in</strong>formation, and any<br />

known shared perspectives with<strong>in</strong> their work place. Some participants balk<br />

when they are asked to conduct the tally and <strong>in</strong>terpret their results. They<br />

express concern about the accuracy of the results (were the raters be<strong>in</strong>g<br />

honest?) and their personal difficulty <strong>in</strong> com<strong>in</strong>g to a conclusion about their<br />

relative strength regard<strong>in</strong>g each item. We listen closely and work with<br />

participants to discover the possible mean<strong>in</strong>g from the multiple perspectives on<br />

each item. Participants are not given “answers”. The practice field opportunity<br />

(behavioural simulation) which follows provides an opportunity for<br />

clarification – from both other programme participants and the tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g staff.<br />

Live practice fields<br />

By the third day <strong>in</strong> the LOMA Middle Management Workshop, we have worked<br />

with several <strong>leadership</strong> concepts and three heuristic models, <strong>in</strong>volved<br />

participants <strong>in</strong> one vicarious learn<strong>in</strong>g experience and small group discussion,<br />

and facilitated their synthesis of the Leadership Inventory feedback from their<br />

co-workers. The stage has been set for their live performances. We use one of<br />

several behavioural simulations designed specifically for <strong>leadership</strong><br />

<strong>development</strong> as the first performance[7], and the trio group process to explore<br />

participant bus<strong>in</strong>ess issues as the second performance.<br />

Behavioural simulations<br />

Behavioural simulations recreate an organizational entity through written<br />

materials and implied structures, roles, and functions. The simulated<br />

organization is part of an <strong>in</strong>dustry; it experiences competitive, economic, legal,<br />

social, political, and regulatory forces just as real organizations do. Individuals<br />

assume different, pre-established and partially-def<strong>in</strong>ed managerial roles <strong>in</strong> the<br />

simulated organization. They then have the opportunity to establish priorities,<br />

relationships, goals, a vision, or whatever else they view as appropriate to<br />

managerial work. Individually and collectively the participants enact an<br />

organization with<strong>in</strong> an environment.<br />

Depend<strong>in</strong>g on the goals, styles, and skills of the people <strong>in</strong>volved, different<br />

issues become important, are def<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> different ways, and unique solutions<br />

emerge for similar issues. S<strong>in</strong>ce there is no tangible structure <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>itial<br />

simulation, participants beg<strong>in</strong> with only a slight sense of order. They recognize<br />

the lack of an agreed-on structure or process for lead<strong>in</strong>g the organization and<br />

the threat of slipp<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>to chaos. Over time a <strong>new</strong> order emerges that reflects<br />

their <strong>in</strong>dividual and collective perspectives of both the simulated organization<br />

<strong>Apply<strong>in</strong>g</strong><br />

<strong>new</strong> <strong>science</strong><br />

<strong>theories</strong><br />

47

Journal of<br />

Management<br />

Development<br />

14,5<br />

48<br />

(its issues) and how to lead it. The debrief<strong>in</strong>g process focuses on what the<br />

participants chose to do as well as how they went about do<strong>in</strong>g it.<br />

Behavioural simulations are practice fields for explor<strong>in</strong>g the implications of<br />

<strong>new</strong> <strong>science</strong> concepts <strong>in</strong> work organizations. There are no prefixed relationships<br />

among issues or participants. There are no predeterm<strong>in</strong>ed “right answers”. The<br />

<strong>in</strong>structions given to participants for the simulation is to “do what you feel<br />

comfortable do<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> light of the programme concepts that you believe would be<br />

effective <strong>in</strong> this organization”. Thus, participants are encouraged to enter <strong>in</strong>to a<br />

self-organiz<strong>in</strong>g system – they beg<strong>in</strong> with someth<strong>in</strong>g and change it as they<br />

choose, hopefully lead<strong>in</strong>g to a more desirable future for the organization. There<br />

are no real boundaries from a tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g or programme perspective. All<br />

boundaries are self-created and self-imposed on the basis of <strong>in</strong>dividual and<br />

collective mental models of effective <strong>leadership</strong> behaviour.<br />

The debrief<strong>in</strong>g processes that follow the enactment phase of the behavioural<br />

simulation focus on participants learn<strong>in</strong>g about their <strong>leadership</strong> approaches<br />

through reflection and feedback from other participants and staff. Group<br />

discussions, a round-rob<strong>in</strong> peer feedback process, staff counsell<strong>in</strong>g sessions, a<br />

review of participant synthesized multirater <strong>in</strong>formation, and coach<strong>in</strong>g on the<br />

<strong>development</strong> of personal <strong>in</strong>sights help participants personalize their learn<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

to their own organizational situations and style.<br />

Trio group bus<strong>in</strong>ess issue exploration activities<br />

The second live practice field used <strong>in</strong> the LOMA Middle Management<br />

Workshop is a bus<strong>in</strong>ess situation trio group analysis. Here we have participants<br />

focus on a current, unresolved, important bus<strong>in</strong>ess/community issue for which<br />

they are partially responsible. They apply the programme concepts to the issue,<br />

then share it with two other programme peers. This practice field is “live” <strong>in</strong><br />

that the issue and key players <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> the issue are live. An <strong>in</strong>itial plan is<br />

developed to move the issue forward – a plan that frequently needs the cooperation<br />

of many others – both <strong>in</strong>side and outside the participant’s work<br />

organization.<br />

By shar<strong>in</strong>g both the issue and one’s ideas about it with programme peers,<br />

participants are able to explore possible reactions to their <strong>leadership</strong> efforts<br />

before they are enacted. The conversation with<strong>in</strong> trio groups often focuses on<br />

“What if . . . “ and “Have you thought about …” k<strong>in</strong>ds of questions by the<br />

programme peers. Note aga<strong>in</strong> that the trio process does not proceed with<br />

prefixed, def<strong>in</strong>able solutions <strong>in</strong> m<strong>in</strong>d, nor does it conform to a specific order of<br />

question<strong>in</strong>g or response. Conversations often appear to be free-flow<strong>in</strong>g and illstructured,<br />

only to emerge with a sense of direction and order. Trio groups are<br />

self-organiz<strong>in</strong>g systems <strong>in</strong> which each member takes on roles of presenter,<br />

facilitator, and coach <strong>in</strong> a self-determ<strong>in</strong>ed manner.<br />

Develop<strong>in</strong>g personal <strong>in</strong>sights<br />

The f<strong>in</strong>al day of a LOMA Middle Management Workshop guides participants<br />

through a process to develop <strong>in</strong>sights about their personal style, competences,

and <strong>leadership</strong> approach. We use Senge’s[8] framework of five discipl<strong>in</strong>es of<br />

learn<strong>in</strong>g to stimulate <strong>in</strong>sights <strong>in</strong> the areas of personal mastery, develop<strong>in</strong>g and<br />

understand<strong>in</strong>g one’s own and others’ mental models, creat<strong>in</strong>g a shared vision,<br />

team learn<strong>in</strong>g, and systems th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g. The refram<strong>in</strong>g of the workshop along<br />

these discipl<strong>in</strong>es helps participants generalize the learn<strong>in</strong>gs from the specific<br />

activities, cases, simulation, and trio group bus<strong>in</strong>ess issues to their ongo<strong>in</strong>g<br />

work lives.<br />

Contrast the closure experience of develop<strong>in</strong>g personal <strong>in</strong>sights and<br />

sometimes shar<strong>in</strong>g them with other participants used here (and <strong>in</strong> other Center<br />

for Leadership activities) with the more traditional test<strong>in</strong>g approach. Most tests<br />

require one to identify what are predeterm<strong>in</strong>ed right answers based on the<br />

content covered <strong>in</strong> the <strong>development</strong>al experience. As we apply <strong>new</strong> <strong>science</strong><br />

concepts to <strong>leadership</strong> <strong>development</strong>, we beg<strong>in</strong> to accept the notion that different<br />

people will learn different th<strong>in</strong>gs and use their learn<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong> different ways. This<br />

is what our personal <strong>in</strong>sight activities are <strong>in</strong>tended to precipitate – unique but<br />

powerful learn<strong>in</strong>gs for the <strong>in</strong>dividual <strong>in</strong> light of their perceptions of reality, their<br />

ability to participate <strong>in</strong> self-organiz<strong>in</strong>g systems, and their capacity to thrive on<br />

chaos.<br />

Notes and references<br />

1. Wheatley, M. J., Leadership and the New Science: Learn<strong>in</strong>g about Organization from an<br />

Orderly Universe, Berrett-Koehler Publishers, San Francisco, CA, 1992.<br />

2. While started at NYU, the virtual organization today encompasses the ideas and<br />

<strong>in</strong>volvement of people from more than ten universities and dozens of work organizations.<br />

Those that have most directly affected my th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g are Cather<strong>in</strong>e Ahern, Maria Arnone,<br />

Deborah Barrows, Hrach Bedrosian, Susan Berger, William Berl<strong>in</strong>er, Sabra Brock, Jim<br />

Clark, Ron Clark, Joel DeLuca, Susan DeLuca, David DeVries, Roger Dunbar, Jane Dutton,<br />

Andy Flem<strong>in</strong>g, Dana Fogg, Richard Green, Abraham Gitlow, Anne Hayden, Karen<br />

Hartman, Robert Hawk<strong>in</strong>s, Susan He<strong>in</strong>buch, Robert Kaplan, Morgan McCall, Mary<br />

McBride, Thomas Mullen, Sidney Nachman, Monica Shay, Candace Ulrich, Ronald<br />

Vaughn, Karen Watson, and Dale Zand.<br />

3. Stumpf, S.A. and Mullen, T., Tak<strong>in</strong>g Charge: Strategic Leadership <strong>in</strong> the Middle Game,<br />

Prentice-Hall, New York, NY, 1992.<br />

4. Stumpf, S.A., The Growth Challenge: How to Build Your Bus<strong>in</strong>ess Profitably, Dearborn<br />

F<strong>in</strong>ancial Publish<strong>in</strong>g, Chicago, IL, 1993.<br />

5. Stumpf, S.A. and DeLuca, J., Learn<strong>in</strong>g to Use What You Already Know, Berrett-Koehler<br />

Publishers, San Francisco, CA, 1994.<br />

6. Stumpf, S.A. and Dutton, J.E., “The dynamics of learn<strong>in</strong>g through management<br />

simulations: let’s dance”, Journal of Management Development, Vol. 9 No. 2, 1990, pp. 7-15.<br />

7. Dunbar, R., Stumpf, S.A., Mullen, T. and Arnone, M., “Management <strong>development</strong>: choos<strong>in</strong>g<br />

the right <strong>leadership</strong> simulation for the task”, Journal of Management Education, Vol. 16<br />

No. 2, 1992, pp. 220-30.<br />

8. Senge, P., The Fifth Discipl<strong>in</strong>e: The Art and Practice of the Learn<strong>in</strong>g Organization,<br />

Doubleday/Currency, New York, NY, 1990.<br />

<strong>Apply<strong>in</strong>g</strong><br />

<strong>new</strong> <strong>science</strong><br />

<strong>theories</strong><br />

49