Who earns minimum wages in Europe - European Trade Union ...

Who earns minimum wages in Europe - European Trade Union ...

Who earns minimum wages in Europe - European Trade Union ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

.....................................................................................................................................<br />

<strong>Who</strong> <strong>earns</strong> <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong><br />

<strong>wages</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Europe</strong>?<br />

New evidence based on household surveys<br />

—<br />

François Rycx and Stephan Kampelmann<br />

.....................................................................................................................................<br />

Report 124

<strong>Who</strong> <strong>earns</strong> <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong><br />

<strong>wages</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Europe</strong>?<br />

New evidence based on household surveys<br />

—<br />

François Rycx and Stephan Kampelmann<br />

Report 124<br />

european trade union <strong>in</strong>stitute

Brussels, 2012<br />

© Publisher: ETUI aisbl, Brussels<br />

All rights reserved<br />

Pr<strong>in</strong>t: ETUI Pr<strong>in</strong>tshop, Brussels<br />

D/2012/10.574/25<br />

ISBN: 978-2-87452-271-0 (pr<strong>in</strong>t version)<br />

ISBN: 978-2-87452-273-4 (electronic version)<br />

The ETUI is f<strong>in</strong>ancially supported by the <strong>Europe</strong>an <strong>Union</strong>. The <strong>Europe</strong>an <strong>Union</strong> is not<br />

responsible for any use made of the <strong>in</strong>formation conta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> this publication.

Contents<br />

Executive summary ................................................................................................................................... 5<br />

1. Introduction: M<strong>in</strong>imum <strong>wages</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Europe</strong> ................................................................................ 13<br />

2. The study of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong>: state of the art ..................................................................... 16<br />

2.1 General issues addressed by the economic literature ............................................... 16<br />

2.2 Central concepts for the analysis of the “bite” of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> ..................... 17<br />

2.3 Exist<strong>in</strong>g comparative studies and available databases ............................................. 21<br />

2.4 Typology of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage systems ............................................................................... 23<br />

3. M<strong>in</strong>imum <strong>wages</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Europe</strong>: empirical results ........................................................................ 26<br />

3.1 The qualitative dimension: the <strong>Europe</strong>an diversity<br />

of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage systems .................................................................................................. 26<br />

3.2 The quantitative dimension: employment <strong>in</strong>cidence, Kaitz <strong>in</strong>dices<br />

and characteristics of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage earners (and their households) .............. 27<br />

3.3 Regression analysis ................................................................................................................ 43<br />

4. Summary and suggestions for further research ................................................................... 48<br />

Statistical appendix ................................................................................................................................ 51<br />

Bibliography .............................................................................................................................................. 63<br />

Report 124<br />

3

Executive summary<br />

Context and objectives<br />

After a period of neglect dur<strong>in</strong>g the 1980s and 1990s, <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> have<br />

re-appeared on political agendas <strong>in</strong> several <strong>Europe</strong>an countries. Although<br />

their critics regularly warn aga<strong>in</strong>st potentially negative effects, notably as<br />

regards low-wage employment, wage floors are widely regarded as useful<br />

<strong>in</strong>struments to protect low-wage workers and to combat ris<strong>in</strong>g levels of<br />

<strong>in</strong>equality and poverty.<br />

Today, the <strong>Europe</strong>an <strong>Union</strong> stands out as a traditional stronghold of this type<br />

of labour market policy. With<strong>in</strong> the <strong>Union</strong>, however, there is much diversity<br />

as to the national systems govern<strong>in</strong>g the fix<strong>in</strong>g, implementation, and<br />

monitor<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong>. What is more, the persist<strong>in</strong>g differences<br />

among <strong>Europe</strong>an countries with respect to the overall level and distribution<br />

of <strong>wages</strong> create <strong>in</strong>ternational variations <strong>in</strong> the level and bite of exist<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong>. The current context of widen<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>come <strong>in</strong>equality and a<br />

tight low-wage labour market <strong>in</strong> several Member States might not only<br />

accentuate these differences, but is also likely to generate further <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> as a policy to counter these tendencies.<br />

This study sets out to provide a comprehensive, evidence-based, and up-todate<br />

assessment of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> <strong>in</strong> a range of <strong>Europe</strong>an countries. A first<br />

step towards a better understand<strong>in</strong>g of where <strong>Europe</strong> stands today on this<br />

issue requires to grasp the diversity of <strong>Europe</strong>an <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage systems, a<br />

key objective of the study at hand. The second objective is to document<br />

<strong>in</strong>ternational differences <strong>in</strong> the so-called "bite" of the <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage. This<br />

leads to questions such as "how do national <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> compare to the<br />

overall wage distribution?" and "how many people earn <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> <strong>in</strong><br />

each country?" that are assessed for a set of n<strong>in</strong>e countries from Western,<br />

Central and Eastern <strong>Europe</strong>: Belgium, Bulgaria, Germany, Hungary, Ireland,<br />

Poland, Romania, Spa<strong>in</strong>, and the United K<strong>in</strong>gdom. This sample was designed<br />

to <strong>in</strong>clude countries for which recent evidence has been miss<strong>in</strong>g prior to this<br />

report; <strong>in</strong>deed, recent <strong>in</strong>formation on <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> <strong>in</strong> Central and Eastern<br />

<strong>Europe</strong>an countries is urgently needed to compare the labour market<br />

outcomes <strong>in</strong> different geographical areas of the <strong>Union</strong>. The report also<br />

<strong>in</strong>cludes Belgium and Germany as examples of countries with complex<br />

<strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage systems that are unfortunately not treated <strong>in</strong> many<br />

comparative studies. What is more, the study also overcomes the narrow<br />

focus of extant overviews that have typically focussed only on full-time<br />

employment.<br />

Report 124<br />

5

François Rycx and Stephan Kampelmann<br />

Crucially, the study improves on exist<strong>in</strong>g work by look<strong>in</strong>g beyond aggregate<br />

numbers; it provides a detailed panorama of the population of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong><br />

wage earners <strong>in</strong> each country under <strong>in</strong>vestigation, notably by describ<strong>in</strong>g their<br />

composition <strong>in</strong> terms of a range of socio-demographic characteristics.<br />

Grasp<strong>in</strong>g the diversity of <strong>Europe</strong>an <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage<br />

systems<br />

<strong>Europe</strong>an countries are not homogeneous with respect to their <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong><br />

wage policies. Indeed, <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage systems typically reflect the wider<br />

<strong>in</strong>stitutional context of national labour markets as well as their historical<br />

development. The formerly socialist economies of Central and Eastern<br />

<strong>Europe</strong>an countries are a case <strong>in</strong> po<strong>in</strong>t. Dur<strong>in</strong>g the transition from planned to<br />

market economies, these countries typically developed <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage<br />

policies without the back<strong>in</strong>g of strong collective barga<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>stitutions. As a<br />

result, many of them today operate systems <strong>in</strong> which a s<strong>in</strong>gle wage floor is<br />

fixed at the national level - contrary to countries with strong traditions of<br />

sectoral barga<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g like Italy or Sweden where trade unions negotiate<br />

different m<strong>in</strong>ima for each sector.<br />

In order to grasp the diversity of <strong>Europe</strong>an <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage systems, the study<br />

uses a straightforward typology that has both <strong>in</strong>tuitive appeal and fits the<br />

empirical results. It dist<strong>in</strong>guishes between two types of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage<br />

systems:<br />

— Type I: the <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage that applies to most workers and employees<br />

is determ<strong>in</strong>ed through the decision of a governmental agency or<br />

collective barga<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g at the national level. In its ideal-typical form, such<br />

a system leads to a clean cut <strong>in</strong> the wage distribution at the level of the<br />

national <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage.<br />

— Type II: the <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage that applies to most workers and employees<br />

is determ<strong>in</strong>ed at the <strong>in</strong>fra-national level, for <strong>in</strong>stance <strong>in</strong> sector or regional<br />

negotiations. The ideal-type of this system <strong>in</strong>cludes many different<br />

m<strong>in</strong>ima so that no clear truncation is visible at any particular po<strong>in</strong>t of the<br />

wage distribution. This type of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage system is referred to as a<br />

"complex system".<br />

This typology reveals a geographical stratification of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage systems.<br />

All of the Nordic countries operate <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage system that are "complex",<br />

i.e. many different m<strong>in</strong>ima co-exist side by side. By contrast, the new<br />

Members States from Central and Eastern <strong>Europe</strong> have "clean-cut" systems,<br />

i.e. the wage distribution is truncated by a <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage that applies to<br />

most workers. The Anglo-Saxon countries <strong>in</strong> the sample (United K<strong>in</strong>gdom<br />

and Ireland) also established systems that apply if not a s<strong>in</strong>gle, but<br />

nevertheless a small number of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> at the national level.<br />

Western Cont<strong>in</strong>ental and Southern <strong>Europe</strong> cannot be classified <strong>in</strong>to one of the<br />

6 Report 124

<strong>Who</strong> <strong>earns</strong> <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Europe</strong> ?<br />

two types: while Austria, Belgium, Germany, Greece, and Italy have complex<br />

<strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage systems, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Cyprus, Spa<strong>in</strong>, and<br />

Portugal resemble more the clean-cut type.<br />

Level of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> and <strong>in</strong>cidence of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong><br />

wage earners<br />

There are two ways to assess the "bite" of a given <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage: (a)<br />

compar<strong>in</strong>g its absolute level across countries and its relative to the national<br />

median wage and (b) look<strong>in</strong>g at the proportion of the labour force that <strong>earns</strong><br />

<strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong>. The computation of both statistics is tedious due to the coexistence<br />

of many different <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> with<strong>in</strong> most countries. While the<br />

range of different m<strong>in</strong>ima is relatively narrow <strong>in</strong> some countries (<strong>in</strong> 2007, the<br />

lowest m<strong>in</strong>ima <strong>in</strong> Bulgaria was 0.48 and the highest 0.53 euros per hour),<br />

other countries apply rather unequal rates to different segments of the labour<br />

market (<strong>in</strong> the UK, the lowest <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>in</strong> 2007 was 4.85 and the highest<br />

<strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> 7.86 euros).<br />

The study deals with this difficulty by comput<strong>in</strong>g employment-weighted<br />

averages of the different national m<strong>in</strong>ima, both absolute and relative to the<br />

national median wage. The latter is a common measure typically referred to<br />

as the Kaitz <strong>in</strong>dex. Spa<strong>in</strong> has a very low Kaitz <strong>in</strong>dex of 39.3, which means that<br />

the employment-weighted average of the different <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> <strong>in</strong> Spa<strong>in</strong><br />

amounts to around 40 per cent of the Spanish median wage. Bulgaria (41.0),<br />

Romania (44.4), and Poland (47.5) also have relatively low Kaitz <strong>in</strong>dices,<br />

contrary to Ireland (52.6) or Hungary (57.0).<br />

Countries with high Kaitz <strong>in</strong>dices tend to have a bigger share of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong><br />

wage earners: the higher a <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage is relative to the middle of the<br />

wage distribution, the more people fall with<strong>in</strong> its range. This relationship<br />

comes out <strong>in</strong> the study: as much as 11.5 per cent of Hungarians earn <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong><br />

<strong>wages</strong>, but only 3.8 per cent of Spaniards.<br />

In countries like Belgium, Germany, Italy, or Sweden, the national level is not<br />

the most relevant focus of analysis s<strong>in</strong>ce sectoral <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong><br />

predom<strong>in</strong>ate <strong>in</strong> these countries. However, the complexity of sectoral<br />

barga<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g is such that hardly any statistical <strong>in</strong>formation on Kaitz <strong>in</strong>dices or<br />

the number of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> earners is available for complex <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage<br />

systems. The study provides novel evidence <strong>in</strong> this regard and estimated the<br />

average of sectoral m<strong>in</strong>ima <strong>in</strong> Belgium at 59.6 per cent of the Belgium median<br />

wage. The Kaitz <strong>in</strong>dex for Germany is estimated at 57.8 per cent. This suggests<br />

that <strong>in</strong> countries with complex systems, the observed wage floors are<br />

relatively high compared to countries with clean-cut systems. Accord<strong>in</strong>gly,<br />

more people tend to earn (sectoral) <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> <strong>in</strong> these countries. In<br />

Belgium, for <strong>in</strong>stance, the study estimates that 11.4 per cent of the labour<br />

force receives sectoral m<strong>in</strong>ima.<br />

Report 124<br />

7

François Rycx and Stephan Kampelmann<br />

Characteristics of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage earners and their<br />

households<br />

<strong>Trade</strong> unions and policy makers <strong>in</strong> favour of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> typically argue<br />

that the livelihoods of people with low <strong>in</strong>comes are improved after<br />

<strong>in</strong>troduc<strong>in</strong>g wage floors or <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g exist<strong>in</strong>g m<strong>in</strong>ima. Central for this k<strong>in</strong>d of<br />

argumentation is know<strong>in</strong>g who the people are that are found <strong>in</strong> the lower<br />

portion of the <strong>in</strong>come distribution. However, experts on <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong><br />

know surpris<strong>in</strong>gly little about the composition of the group of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage<br />

earners. On this po<strong>in</strong>t, the study provides new <strong>in</strong>sights by compar<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> earners to the rest of the labour force with respect to a range of<br />

socio-demographic and job characteristics.<br />

As for the <strong>in</strong>dividual characteristics of workers and employees, the study<br />

notably looks at age, sex, and educational atta<strong>in</strong>ment. Although there is some<br />

diversity among the countries covered <strong>in</strong> the sample, <strong>in</strong> all of them the<br />

population of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage earners is similar <strong>in</strong> that it is characterised by:<br />

— a lower average age;<br />

— on average more female employment;<br />

— lower levels of educational atta<strong>in</strong>ment than workers with higher <strong>wages</strong>.<br />

Regard<strong>in</strong>g job characteristics, the study compares the two sub-populations<br />

with respect to the share of temporary work contracts and the <strong>in</strong>cidence of<br />

part-time jobs. The latter has been def<strong>in</strong>ed as employments whose average<br />

weekly work hours do not exceed 35 hours. Aga<strong>in</strong>, the data reveals a clear<br />

difference between the two sub-populations <strong>in</strong> all countries. In particular, the<br />

group of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> earners stands out as conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g:<br />

— a considerably higher share of employees with temporary work contracts;<br />

— a higher share of part time employment than the sub-population with<br />

higher <strong>wages</strong>.<br />

What are the overall liv<strong>in</strong>g conditions of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage earners? To shed light<br />

on this question, the report exploits harmonized survey <strong>in</strong>formation on<br />

household characteristics like the average household size, the total disposable<br />

household <strong>in</strong>come, and the risk of poverty. All countries <strong>in</strong> the sample show a<br />

similar pattern <strong>in</strong> terms of household size: the population of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage<br />

earners consistently live <strong>in</strong> households that are on average larger compared to<br />

the population with higher <strong>wages</strong>. Unsurpris<strong>in</strong>gly, the average disposable<br />

household <strong>in</strong>come is also consistently lower <strong>in</strong> households with <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong><br />

wage earners. F<strong>in</strong>ally, <strong>in</strong> most of the countries <strong>in</strong> the sample, the risk of<br />

poverty of the household is on average considerably higher for the population<br />

of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage earners.<br />

8 Report 124

Ma<strong>in</strong> f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

<strong>Who</strong> <strong>earns</strong> <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Europe</strong> ?<br />

M<strong>in</strong>imum <strong>wages</strong> cont<strong>in</strong>ue to stir controversial policy debates. The current<br />

economic climate <strong>in</strong> <strong>Europe</strong> might contribute to <strong>in</strong>crease the pressure on<br />

<strong>wages</strong> at the bottom of the wage distribution and, as a consequence, renew the<br />

<strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> wage floors as a tool to protect workers and employees. This study<br />

contributes to a better understand<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> by provid<strong>in</strong>g a solid<br />

empirical assessment of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage policies and their socio-economic<br />

consequences for a range of <strong>Europe</strong>an countries.<br />

An obstacle to provid<strong>in</strong>g comparable <strong>in</strong>formation on wage m<strong>in</strong>ima for<br />

different countries is the <strong>in</strong>stitutional diversity of <strong>Europe</strong>an <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage<br />

systems. This diversity reflects the historical evolution of each of the national<br />

collective barga<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g systems. While one has to acknowledge the existence of<br />

national idiosyncrasies, it is nevertheless useful to dist<strong>in</strong>guish <strong>Europe</strong>an<br />

countries with the help of a straightforward typology. Central and Eastern<br />

<strong>Europe</strong>an countries, the UK and Ireland, as well as Luxembourg, the<br />

Netherlands, Cyprus, Spa<strong>in</strong>, and Portugal operate <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage systems<br />

that produce a "clean cut" <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>come distribution. By contrast, all of the<br />

Nordic countries, Austria, Belgium, Germany, Greece, and Italy operate<br />

<strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage systems that are "complex", i.e. many different m<strong>in</strong>ima coexist<br />

side by side so that the left tail of the wage distribution is much smoother<br />

<strong>in</strong> these countries.<br />

In addition to qualitative differences between <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage systems, the<br />

report documents <strong>in</strong>ternational variations <strong>in</strong> the (absolute and relative) levels<br />

of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong>. While these levels follow no clear geographical pattern, it<br />

appears that complex systems are more likely to generate relatively high wage<br />

floors compared to systems that determ<strong>in</strong>e a s<strong>in</strong>gle wage <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> at the<br />

national level.<br />

An important contribution of the report is to provide a statistical panorama of<br />

the population of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage earners. Compared to the rest of the<br />

population, the empirical results show that this group is characterised by a<br />

lower average age; on average more female employment; lower levels of<br />

educational atta<strong>in</strong>ment than workers with higher <strong>wages</strong>; a considerably<br />

higher share of employees with temporary work contracts; and a higher share<br />

of part time employment than the sub-population with higher <strong>wages</strong>. Even<br />

more important <strong>in</strong> terms of the affected <strong>in</strong>dividuals' well be<strong>in</strong>g is the f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g<br />

that <strong>in</strong> all countries <strong>in</strong> the sample <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage earners live <strong>in</strong> bigger<br />

households that dispose of significantly lower <strong>in</strong>come and that are at a higher<br />

risk of liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> poverty.<br />

Report 124<br />

9

François Rycx and Stephan Kampelmann<br />

Figures and table: Distributions and m<strong>in</strong>ima <strong>in</strong><br />

different types of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage systems<br />

Figure a Example of a clean-cut system<br />

0 2 4 6 8<br />

percent<br />

10 Report 124<br />

Bulgaria (2007)<br />

0 1 2 3 4 5<br />

gross hourly wage (euros)<br />

Figure b Example of a complex system<br />

0 2 4 6 8 10<br />

percent<br />

Belgium (2007)<br />

0 10 20 30 40 50<br />

gross hourly wage (euros)<br />

Source: EU-SILC; current 2007 euros; th<strong>in</strong> vertical l<strong>in</strong>es represent levels of exist<strong>in</strong>g m<strong>in</strong>ima <strong>wages</strong> <strong>in</strong> each country.

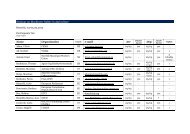

Table a Level of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong>, share of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage earners, and Kaitz <strong>in</strong>dices per country (2007)<br />

Share of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage earners accord<strong>in</strong>g to different<br />

<strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> (per cent)<br />

Employment-weighted Kaitz <strong>in</strong>dex accord<strong>in</strong>g<br />

to different <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> (per cent) 2<br />

Level of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> (current euros)<br />

M<strong>in</strong>imum wage<br />

equal to 50 per cent<br />

of median wage<br />

Sector<br />

<strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong><br />

wage<br />

Interprofessional<br />

<strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage<br />

Sector <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong><br />

wage<br />

Interprofessional<br />

<strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage<br />

Employmentweighted<br />

average<br />

of m<strong>in</strong>ima2 Highest<br />

<strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong><br />

Lowest<br />

<strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong><br />

Obs.<br />

TYPE I COUNTRIES<br />

12.2<br />

4.7<br />

—<br />

—<br />

5.8<br />

—<br />

—<br />

41.0<br />

57.0<br />

0.53<br />

1.51<br />

0.53<br />

1.51<br />

0.48<br />

1.51<br />

3904<br />

6513<br />

Bulgaria<br />

Hungary<br />

8.8<br />

11.5<br />

9.2<br />

—<br />

—<br />

—<br />

—<br />

52.6<br />

47.5<br />

8.37<br />

1.42<br />

8.48<br />

1.43<br />

5.93<br />

1.14<br />

3361<br />

10.4<br />

8.3<br />

8.9<br />

4.9<br />

10452<br />

5055<br />

—<br />

—<br />

—<br />

—<br />

44.4<br />

39.9<br />

0.69<br />

3.41<br />

0.69<br />

3.46<br />

0.69<br />

2.42<br />

7.9<br />

7.7<br />

—<br />

3.8<br />

9.5<br />

—<br />

53.2<br />

7.78<br />

7.86<br />

4.85<br />

11327<br />

7029<br />

Ireland<br />

Poland<br />

Romania<br />

Spa<strong>in</strong><br />

United K<strong>in</strong>gdom<br />

TYPE II COUNTRIES<br />

6.6<br />

11.4<br />

14.3<br />

19.0 3<br />

6.9<br />

—<br />

59.6<br />

57.8<br />

51.9<br />

—<br />

9.22<br />

7.63<br />

13.21<br />

12.21<br />

7.80<br />

3.91<br />

5100<br />

8833<br />

Belgium<br />

Germany<br />

<strong>Who</strong> <strong>earns</strong> <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Europe</strong> ?<br />

Notes<br />

1 Germany SOEP, EU-SILC for all other countries<br />

2 Weight<strong>in</strong>g variables depend on differentiation of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong>; employment weighted by sector (and region for Germany)<br />

3 Figure is not corrected for <strong>in</strong>complete collective barga<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g coverage at the sector level; <strong>in</strong> Germany, most sectors do not apply erga omnes rules, i.e. only trade union members are covered by the<br />

<strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage. The figure <strong>in</strong> the table corresponds to the proportion of the German work force that <strong>earns</strong> <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> if an erga omnes rule applied <strong>in</strong> all sectors.<br />

Report 124<br />

11

1. Introduction:<br />

M<strong>in</strong>imum <strong>wages</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Europe</strong><br />

After a phase of “conscious neglect dur<strong>in</strong>g the 1980s and 1990s” (ILO, 2010;<br />

p. 63), <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> 1 have re-appeared on political agendas around the<br />

world. Although their critics regularly warn aga<strong>in</strong>st potentially negative<br />

effects, notably as regards low-wage employment, wage floors are widely<br />

regarded as useful <strong>in</strong>struments to protect low-wage workers and to combat<br />

ris<strong>in</strong>g levels of <strong>in</strong>equality and poverty. Today, <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> exist <strong>in</strong> one<br />

form or another <strong>in</strong> around 90 % of countries <strong>in</strong> the world (ILO, 2010), with<br />

<strong>Europe</strong> stand<strong>in</strong>g out as a traditional stronghold of this type of labour market<br />

policy.<br />

Follow<strong>in</strong>g episodes without mandatory wage floors, the United K<strong>in</strong>gdom and<br />

Ireland adopted statutory national <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> <strong>in</strong> 1999 and 2000,<br />

respectively, thereby jo<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the majority of their <strong>Europe</strong>an neighbours:<br />

Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Spa<strong>in</strong>, France, Latvia, Lithuania,<br />

Luxembourg, Hungary, Malta, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania,<br />

Slovenia, and Slovakia. Two Candidate Countries for Membership <strong>in</strong> the<br />

<strong>Europe</strong>an <strong>Union</strong> also have national statutory <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> (Croatia and<br />

Turkey). Belgium and Greece have a national <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage too, but it is set<br />

by collective barga<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g agreements (<strong>in</strong> Belgium the collective agreement<br />

acquires legal force by royal decree and supplemented by sectoral m<strong>in</strong>ima).<br />

Two Member States of the <strong>Europe</strong>an <strong>Union</strong> ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> a system of statutory<br />

national <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> that does not cover the majority of employees:<br />

Germany and Cyprus. In the former, <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> are set for specific<br />

sectors under the provisions of the Posted Workers Act (Arbeitnehmer<br />

Entsendegesetz). The Cypriot <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> are def<strong>in</strong>ed for a restricted<br />

number of occupational groups (salesmen, clerks, auxiliary health care staff<br />

and auxiliary staff <strong>in</strong> nursery schools, crèches and schools). A somewhat<br />

similar system exists <strong>in</strong> the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, a<br />

Candidate Country, where national m<strong>in</strong>ima are collectively negotiated for full<br />

time employees <strong>in</strong> the textile, leather, and shoes <strong>in</strong>dustry. F<strong>in</strong>ally, there are<br />

several <strong>Europe</strong>an countries without national statutory <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong>:<br />

Austria, Denmark, Italy, F<strong>in</strong>land, Sweden, Iceland, Norway, and Switzerland.<br />

However, sector-level agreements often have erga omnes applicability <strong>in</strong><br />

these countries and therefore function as a collectively negotiated <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong><br />

wage.<br />

1. This report def<strong>in</strong>es "<strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong>" as <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g not only statutory wage floors, but also m<strong>in</strong>ima<br />

that are def<strong>in</strong>ed through collective barga<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g at national and/or sectoral level. An overview about<br />

the different mechanisms through which <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> are set <strong>in</strong> <strong>Europe</strong> is provided below<br />

(see Table 2).<br />

Report 124<br />

13

François Rycx and Stephan Kampelmann<br />

Advocates of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> typically use one of the two follow<strong>in</strong>g<br />

arguments to defend the <strong>in</strong>troduction or <strong>in</strong>crease of wage floors. They<br />

typically argue that <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> (a) affect the wage distribution so as to<br />

reduce overall wage <strong>in</strong>equality and/or (b) directly improve the liv<strong>in</strong>g<br />

conditions of workers <strong>in</strong> the lower tail of the wage distribution.<br />

Unfortunately, scholars of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> know little about some of the<br />

basic statistical facts that underp<strong>in</strong> both types of argumentation.<br />

In order to provide a sound statistical basis for the first argument, one would<br />

arguably want to know more about how the observed diversity of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong><br />

wage systems is l<strong>in</strong>ked to <strong>in</strong>ternational variations <strong>in</strong> the shapes of wage<br />

distributions. On this po<strong>in</strong>t, we document how two types of systems generate<br />

contrast<strong>in</strong>g wage distributions: countries operat<strong>in</strong>g "clean-cut systems" are<br />

associated with wage distributions that are truncated at the level of the<br />

<strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong>; <strong>in</strong> this type of system, the <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage affects a very<br />

specific segment of the distribution. By contrast, <strong>in</strong> "complex systems" many<br />

different m<strong>in</strong>ima co-exist so that the left tail of the distribution is more or less<br />

bell-shaped; as a consequence, <strong>in</strong> these countries <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage policies<br />

affect <strong>in</strong>dividuals at different strata of the distribution, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g relatively<br />

well-paid groups.<br />

Also the second argument raises fundamental questions that have not yet<br />

been answered satisfactorily <strong>in</strong> the literature. These questions <strong>in</strong>clude: How<br />

many people earn <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> <strong>in</strong> Northern, Western, Central, or Eastern<br />

<strong>Europe</strong>an countries? Most extant studies on this question are outdated and<br />

exclude several key countries from Central and Eastern <strong>Europe</strong>. Crucially, we<br />

also still know little about the people that are affected by <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage<br />

policies. For <strong>in</strong>stance, to what extent do they differ from the rest of the labour<br />

force <strong>in</strong> terms of <strong>in</strong>dividual, job, and household characteristics ?<br />

This report presents comprehensive statistical <strong>in</strong>formation allow<strong>in</strong>g to map<br />

the impact of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Europe</strong>. While statistics on the general level<br />

of national statutory <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> are published by <strong>in</strong>ternational data<br />

providers on an annual basis, detailed <strong>in</strong>formation on specific groups of<br />

employees has to be computed from <strong>in</strong>dividual-level labour market surveys.<br />

The results of this report are based on large, representative surveys with<br />

micro-data for a set of <strong>Europe</strong>an countries: the <strong>Europe</strong>an <strong>Union</strong> Survey on<br />

Income and Liv<strong>in</strong>g Conditions (EU-SILC) and the German Socio-economic<br />

panel (GSOEP).<br />

14 Report 124

Outl<strong>in</strong>e of the report<br />

<strong>Who</strong> <strong>earns</strong> <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Europe</strong> ?<br />

The overall objective of this report is to provide statistical evidence on the<br />

impact of the <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage on <strong>Europe</strong>an labour markets. This objective has<br />

been addressed <strong>in</strong> two complementary steps, one of conceptual (Section 2)<br />

and the other of empirical (Section 3) character.<br />

Section 2 presents a review of the literature on <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> and<br />

summarizes the central issues addressed by the extensive research <strong>in</strong> this<br />

area. We also recapitulate the key concepts for the analysis of the “bite” of<br />

<strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> as well as exist<strong>in</strong>g data. In order to grasp the <strong>in</strong>ternational<br />

diversity of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage policies, we <strong>in</strong>troduce a typology of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong><br />

wage systems that contrasts "clean-cut systems" (mostly found <strong>in</strong> the new<br />

Members States and Anglo-Saxon countries) and "complex systems" (such as<br />

Italy, Germany, Belgium, and the Nordic countries).<br />

Turn<strong>in</strong>g to the empirical part of the report, Section 3 presents qualitative and<br />

quantitative data on <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> for a selection of n<strong>in</strong>e countries from<br />

Western, Central and Eastern <strong>Europe</strong>: Belgium, Bulgaria, Germany, Hungary,<br />

Ireland, Poland, Romania, Spa<strong>in</strong>, and the United K<strong>in</strong>gdom. Draw<strong>in</strong>g on the<br />

typology of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage systems, this section documents the l<strong>in</strong>k between<br />

the <strong>in</strong>ternational diversity <strong>in</strong> the way <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> are set and the shapes<br />

of observed wage distributions (Section 3.1).<br />

Section 3.2 <strong>in</strong>vestigates for each country how many and what k<strong>in</strong>d of people<br />

earn <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> at the national and sector level. We present a series of<br />

empirical results that measure different aspects of the bite of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong><br />

<strong>wages</strong>, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g estimates of the Kaitz <strong>in</strong>dex; the size and composition of the<br />

employment spike around the <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage at the national and sector level;<br />

and the <strong>in</strong>dividual, job, and household characteristics of the population of<br />

<strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage earners. In particular, we assess for each of the selected<br />

countries the relationship between <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> and age, sex, level of<br />

education, temporary work, work<strong>in</strong>g time, sector of activity, household size,<br />

household <strong>in</strong>come, and poverty risk. We also carried out a scenario analysis<br />

that looks at the employment consequences of a hypothetical policy that<br />

would <strong>in</strong>troduce a <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage fixed at 50 % of the national median wage<br />

<strong>in</strong> all n<strong>in</strong>e countries covered by this study.<br />

In order to assess the relative impact of <strong>in</strong>dividual and job characteristics on<br />

the likelihood of earn<strong>in</strong>g a <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage, the report also provides results of<br />

a logistic regression for each of the countries <strong>in</strong> the sample (Section 3.3). The<br />

f<strong>in</strong>al section summarizes the conceptual and empirical f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs and suggests<br />

directions for further research on <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Europe</strong>.<br />

Report 124<br />

15

2. The study of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong>:<br />

state of the art<br />

2.1 General issues addressed by the economic<br />

literature<br />

S<strong>in</strong>ce the early 20th century, economists have been engaged <strong>in</strong> vivid academic<br />

controversies on <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong>. Over time, this vast body of literature has<br />

grown beyond the possibility of synthesis. In what follows we will highlight<br />

some of the ma<strong>in</strong> issues addressed <strong>in</strong> the academic literature on wage floors.<br />

By far the most controversially and frequently discussed issue are the<br />

employment effects of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong>. Although the conventional textbook<br />

labour market model clearly predicts disemployment effects follow<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

<strong>in</strong>troduction of a b<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage (Stigler, 1946; Cahuc and<br />

Zylberberg, 2004), a theoretical case for positive employment effects has also<br />

been formulated (notably by Card and Krueger, 1995). In light of this<br />

theoretical ambiguity, economists have mobilised a variety of methods (timeseries<br />

analysis, cross-section and panel data, controlled experiments rely<strong>in</strong>g<br />

on difference-<strong>in</strong>-differences estimators, identification of substitution and<br />

scale effects, dist<strong>in</strong>ction between effects on employment and hours, etc) <strong>in</strong> an<br />

on-go<strong>in</strong>g attempt to measure the underly<strong>in</strong>g employment elasticities. This<br />

body of research failed to establish a last<strong>in</strong>g consensus, with some researchers<br />

conclud<strong>in</strong>g from extant evidence that employment elasticities are<br />

significantly negative (Brown et al. 1982; Neumark and Wascher, 2004,<br />

2008), while others defend the opposite conclusion (Card and Krueger, 1995).<br />

A reconciliatory position <strong>in</strong> this debate is the view that any employment<br />

effects (be their positive or negative) are probably very small (Kennan, 1995;<br />

Dolado et al., 1996; ILO, 2010).<br />

A second group of issues concerns the impact of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> on the<br />

<strong>in</strong>dividual <strong>in</strong>come distribution, the household <strong>in</strong>come distribution, and<br />

poverty. These issues are of course related to the first one given that one needs<br />

to make assumptions about potential employment consequences <strong>in</strong> order to<br />

anticipate the effects of a <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage on <strong>in</strong>equality or poverty. Typically,<br />

economists have attempted to measure the net result of two effects: the<br />

(positive or negative) employment effect that results from changes <strong>in</strong> labour<br />

demand, and a (positive) wage effect that accrues to <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage earners<br />

that rema<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> employment.<br />

The impact of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> on <strong>in</strong>equality and poverty also raises a range<br />

of new questions: To what extent do <strong>in</strong>creases <strong>in</strong> <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> lead to<br />

hikes <strong>in</strong> other <strong>wages</strong> ? Do <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong>-wage earners live <strong>in</strong> households situated<br />

16 Report 124

<strong>Who</strong> <strong>earns</strong> <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Europe</strong> ?<br />

at the bottom, middle, or top of the (<strong>in</strong>dividual or household) <strong>in</strong>come<br />

distribution ? And are they ma<strong>in</strong>ly young workers that will “grow out” of<br />

<strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage jobs as they move up career ladders, or are other age groups<br />

for whom <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> could be a more permanent prospect also<br />

affected ?<br />

A range of studies suggest that a substantial share of the benefits of higher<br />

<strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> accrue <strong>in</strong> households whose <strong>in</strong>comes already lie above<br />

poverty level, and that many <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage earners are teenagers who will<br />

see their earn<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g as they acquire experience and seniority (see the<br />

overviews <strong>in</strong> OECD, 1998; Fairchild, 2004). However, other studies have<br />

found “considerable evidence of a poverty-reduc<strong>in</strong>g effect of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong><br />

<strong>wages</strong>” for some sub-populations (Addison and Blackburn, 1999; p. 404) or a<br />

negative relationship between the <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage and overall <strong>in</strong>equality<br />

(Koeniger, Leonardi and Nunziata, 2007). A serious problem of this literature<br />

is that these questions have been almost exclusively analysed with data from<br />

the United States; especially cross-country comparisons of <strong>in</strong>equality and<br />

poverty effects of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> are rare. This is unfortunate because<br />

national employment systems are likely to <strong>in</strong>fluence the l<strong>in</strong>k between<br />

<strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> and the overall earn<strong>in</strong>gs distribution. For <strong>in</strong>stance, so-called<br />

“knock-on” or “ripple effects”, i.e. the phenomenon that a <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage<br />

hike will <strong>in</strong>duce wage <strong>in</strong>creases higher up <strong>in</strong> the wage distribution, are likely<br />

to depend on the <strong>in</strong>cidence and strength of collective barga<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g,<br />

unionisation, and other country-specific <strong>in</strong>stitutions such as the employment<br />

protection legislation (Dolado et al., 1996; Checci and Lucifora, 2002;<br />

Neumark, Schweitzer and Wascher, 2004).<br />

A third set of questions asks to what extent <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> <strong>in</strong>teract with<br />

other economic variables. This strand of research has attempted to establish<br />

l<strong>in</strong>ks between wage floors and variables such as the general price level,<br />

unemployment, tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g decisions, or economic growth (e.g. Scarpetta, 1996;<br />

Fanti and Gori, 2011). In light of the considerable theoretical and empirical<br />

difficulties to reach robust conclusions on relatively direct consequences of<br />

<strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> (such as their effect on low-wage employment), it is not<br />

surpris<strong>in</strong>g that no consistent evidence has yet emerged on more <strong>in</strong>direct<br />

effects.<br />

2.2 Central concepts for the analysis of the “bite” of<br />

<strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong><br />

All issues mentioned above are clearly relevant to understand the impact of<br />

<strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> for the work<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>Europe</strong>an labour markets. The purpose of<br />

this report is to produce a range of more fundamental statistics that are<br />

currently either outdated or unavailable. Although most of these statistics<br />

will be <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g heuristics for their own sake - e.g. by allow<strong>in</strong>g to document<br />

and to compare the bite of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> across <strong>Europe</strong> - it should be<br />

noted that answer<strong>in</strong>g more analytical questions also requires sound evidence<br />

Report 124<br />

17

François Rycx and Stephan Kampelmann<br />

on both the bite of exist<strong>in</strong>g m<strong>in</strong>ima and the socio-demographic composition<br />

of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage earners. The employment effect of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> is a<br />

case <strong>in</strong> po<strong>in</strong>t: given that different socio-demographic groups typically have<br />

different employment elasticities (Fitzenberger, 2009), a first step <strong>in</strong><br />

estimat<strong>in</strong>g employment consequences is to pa<strong>in</strong>t an accurate picture of the<br />

population of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage earners. Similarly, the impact of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong><br />

<strong>wages</strong> on <strong>in</strong>equality and poverty can only be assessed correctly with detailed<br />

<strong>in</strong>formation on the characteristics of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage earners.<br />

This report sheds light on the impact of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> by apply<strong>in</strong>g state-ofthe<br />

art concepts to micro-data from a set of <strong>Europe</strong>an countries. The bite of<br />

national wage floors can notably be gauged by estimat<strong>in</strong>g different versions of<br />

the “Kaitz <strong>in</strong>dex” and the “employment spike”.<br />

2.2.1 The Kaitz <strong>in</strong>dex<br />

Named after its first formulation <strong>in</strong> Kaitz (1970), this <strong>in</strong>dex is a<br />

straightforward method to relate the absolute level of the <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage to<br />

other <strong>wages</strong>. Indeed, a direct comparison of absolute levels of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong><br />

<strong>wages</strong> is not mean<strong>in</strong>gful if countries differ with respect to the distribution of<br />

productivities: <strong>in</strong> a country with high average productivity, the bite of a<br />

relatively low wage floor might be weak; <strong>in</strong> a low-productivity country,<br />

however, the same <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage could have a much stronger impact.<br />

In its most basic version, the Kaitz <strong>in</strong>dex is def<strong>in</strong>ed as the ratio of the<br />

<strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage to the average wage of the work<strong>in</strong>g population. The Kaitz<br />

<strong>in</strong>dex is thus a measure of the “bite” of the <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage: small values<br />

<strong>in</strong>dicate that the wage floor is a long way from the centre of the earn<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

distribution and its impact therefore potentially low; conversely, a high Kaitz<br />

<strong>in</strong>dex reveals that the <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage is close to the centre of the distribution<br />

and that it potentially affects a larger number of employees. It should be<br />

noted, however, that the Kaitz <strong>in</strong>dex alone does not allow to draw any<br />

conclusion about whether a given level of the <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage is economically<br />

desirable or not: this question can only be addressed with additional<br />

<strong>in</strong>formation such as the structure of wage costs and the productivity of<br />

different types of workers. In addition, as Dolado et al. (1996) po<strong>in</strong>t out, the<br />

Kaitz <strong>in</strong>dex may misrepresent the impact of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> <strong>in</strong> countries<br />

where other <strong>in</strong>stitutions such as benefit systems act as effective wage floors<br />

(ibid., p. 325).<br />

In certa<strong>in</strong> countries, such as Germany or Italy, the computation of Kaitz<br />

<strong>in</strong>dices is relatively complex due to the existence of numerous m<strong>in</strong>ima<br />

negotiated at sector-level. But even for countries with a s<strong>in</strong>gle national<br />

statutory <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> it is often advisable to calculate separate Kaitz <strong>in</strong>dices for<br />

different wage or skill groups <strong>in</strong> order to reflect that the <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage bites<br />

deeper for lower paid employees (<strong>in</strong> this case the numerator of the <strong>in</strong>dex is the<br />

same for all employees, but the denom<strong>in</strong>ator decreases if one considers a<br />

group of employees with lower average earn<strong>in</strong>gs). Indeed, the aggregate Kaitz<br />

18 Report 124

<strong>in</strong>dex may be similar across countries but mask compositional differences<br />

(OECD 1998). In this case, compar<strong>in</strong>g the basic <strong>in</strong>dex between dissimilar<br />

countries might lead to serious mis<strong>in</strong>terpretations. In order to improve its<br />

comparability, several adjustments to the basic Kaitz <strong>in</strong>dex have been<br />

proposed <strong>in</strong> the literature:<br />

— The composition of the population affected by the Kaitz <strong>in</strong>dex might<br />

differ across countries; it is therefore advisable to compare <strong>in</strong>dices for<br />

groups with similar characteristics (such as age, gender, occupation,<br />

educational atta<strong>in</strong>ment, contract type etc.).<br />

— Most <strong>Europe</strong>an countries apply lower sub-m<strong>in</strong>ima for young or<br />

<strong>in</strong>experienced workers (e.g. teenagers), ma<strong>in</strong>ly <strong>in</strong> an attempt to curb<br />

potential disemployment effects for these groups. International<br />

comparability requires the use of different Kaitz <strong>in</strong>dices for groups<br />

affected by sub-m<strong>in</strong>ima.<br />

— Although most analysts compute the <strong>in</strong>dex with average earn<strong>in</strong>gs as<br />

denom<strong>in</strong>ator, us<strong>in</strong>g median earn<strong>in</strong>gs might yield more comparable<br />

results. The reason for this is that countries with higher wage dispersion<br />

also have lower <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> (OECD 1998). A Kaitz <strong>in</strong>dex based on<br />

median earn<strong>in</strong>gs is less affected by the shape of the overall wage<br />

distribution than an <strong>in</strong>dex based on average earn<strong>in</strong>gs.<br />

— International comparisons of Kaitz <strong>in</strong>dices are sensitive to the <strong>in</strong>clusion<br />

of bonuses, overtime, and other additional payments; countries <strong>in</strong> which<br />

the <strong>in</strong>cidence of such payments is large will display a non-adjusted Kaitz<br />

<strong>in</strong>dex (i.e. exclud<strong>in</strong>g additional payments) that overestimates the<br />

effective bite of the <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage.<br />

— Conversely, the basic Kaitz <strong>in</strong>dex can lead to flawed comparisons if gross<br />

earn<strong>in</strong>gs are used <strong>in</strong>stead of net earn<strong>in</strong>gs: the more a country's tax<br />

system is progressive, the more the gross Kaitz <strong>in</strong>dex understates the bite<br />

of the <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage.<br />

— F<strong>in</strong>ally, it is important to take <strong>in</strong>stitutional differences <strong>in</strong>to account when<br />

compar<strong>in</strong>g Kaitz <strong>in</strong>dices. For <strong>in</strong>stance, national labour <strong>in</strong>stitutions differ<br />

<strong>in</strong> the extent to which hikes <strong>in</strong> the <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage are transmitted further<br />

up <strong>in</strong> the wage structure. As a consequence, Dolado et al. (1996) argue<br />

that it is safer to analyse changes over time than cross-country<br />

differences, especially <strong>in</strong> situations of considerable <strong>in</strong>stitutional diversity<br />

between countries.<br />

2.2.2 The employment spike<br />

<strong>Who</strong> <strong>earns</strong> <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Europe</strong> ?<br />

The distance between the wage floor and the centre of the earn<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

distribution is a useful heuristic to measure the bite of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong>. This<br />

be<strong>in</strong>g said, the Kaitz <strong>in</strong>dex alone cannot give a complete picture of the impact<br />

Report 124<br />

19

François Rycx and Stephan Kampelmann<br />

of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong>. The case of Sweden illustrates this po<strong>in</strong>t: although the<br />

Swedish Kaitz <strong>in</strong>dex is relatively high compared to other <strong>Europe</strong>an countries<br />

(Neumark and Wascher (2004) estimate it at 0.52), nobody actually receives<br />

the <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage <strong>in</strong> Sweden. Despite its relatively high level, the Swedish<br />

<strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage fails to bite due to other features of the earn<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

determ<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>in</strong> Sweden, especially the strong <strong>in</strong>cidence of collective<br />

barga<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g. A complementary heuristic for the analysis of the bite of<br />

<strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> is to measure the “spike” of employments that are situated at<br />

or near the <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage. The more employees are clustered around the<br />

<strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong>, the higher is its bite.<br />

To be sure, conventional neoclassical models of the labour market do not<br />

predict any employment spikes. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to such models, the earn<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

distribution will be truncated and workers whose marg<strong>in</strong>al productivity falls<br />

below the <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage will be laid off. Empirical research on wage<br />

distributions has documented, however, that this view is seriously flawed: <strong>in</strong><br />

many countries the existence of a <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage has lead to visible<br />

employment spikes at or near the <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong>. Possible explanations for this<br />

phenomenon are that employers are able to afford at least part of the higher<br />

wage costs, either by tapp<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>to exist<strong>in</strong>g rents (profits) or by pass<strong>in</strong>g these<br />

costs on to consumers. An alternative explanation is that the productivity of<br />

below-<strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> employees can be raised through tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g or organisational<br />

changes so as to make their employment profitable at the <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage.<br />

Similar to the case of the Kaitz <strong>in</strong>dex, cross-country comparability requires<br />

exam<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the employment spike for similar groups of employees. For<br />

<strong>in</strong>stance, an exclusive focus on the spike <strong>in</strong> the overall wage distribution<br />

might overlook differences <strong>in</strong> employment spikes for categories such as<br />

gender, age, occupation, education, sector, etc.<br />

Depend<strong>in</strong>g on the research question, one might also be <strong>in</strong>terested by the size<br />

and characteristics of the population that is remunerated below certa<strong>in</strong><br />

threshold values, for <strong>in</strong>stance when assess<strong>in</strong>g the impact of a hypothetical rise<br />

<strong>in</strong> the <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage (or the Kaitz <strong>in</strong>dex) to a higher level. Such a “shadow<br />

spike” can yield <strong>in</strong>formation on the bite of the hypothetical rise <strong>in</strong> the<br />

<strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage by <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g how many and what types of employees would<br />

be affected <strong>in</strong> such a scenario. It should be noted, however, that the “shadow<br />

spike” can differ substantially from the employment spike that will be<br />

observed if the hypothetical <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage <strong>in</strong>crease is actually implemented.<br />

The difference between the two spikes might stem from several factors: a<br />

higher <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage might attract new employees <strong>in</strong>to the labour force,<br />

thereby chang<strong>in</strong>g its socio-demographic composition; conversely, some<br />

employees <strong>in</strong> the shadow spike might be laid off if the higher <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage<br />

renders their employment unprofitable.<br />

20 Report 124

<strong>Who</strong> <strong>earns</strong> <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Europe</strong> ?<br />

2.3 Exist<strong>in</strong>g comparative studies and available<br />

databases<br />

We identified several extensive databases conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g statistical and/or<br />

qualitative <strong>in</strong>formation on basic features of <strong>Europe</strong>an <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage<br />

systems. First, the OECD M<strong>in</strong>imum Wage Database 2 conta<strong>in</strong>s time series for<br />

some of the ma<strong>in</strong> variables of <strong>in</strong>terest, such as national levels of statutory<br />

m<strong>in</strong>ima (<strong>in</strong> local currencies and PPP-adjusted) and gross Kaitz <strong>in</strong>dices (with<br />

both average and median earn<strong>in</strong>gs as denom<strong>in</strong>ator). The OECD provides<br />

<strong>in</strong>formation on <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> for different pay periods (hourly, weekly,<br />

monthly, annually) and allows to analyse their evolution over the long run: for<br />

some countries, the time-series data goes back to the 1960s (France, Greece,<br />

Luxembourg, Netherlands, Spa<strong>in</strong>). For <strong>Europe</strong>an countries, the OECD<br />

database conta<strong>in</strong>s <strong>in</strong>formation up to the year 2010. A limitation of this source<br />

is that it does not allow to dist<strong>in</strong>guish different groups of employees. All Kaitz<br />

<strong>in</strong>dices are calculated with reference to full-time employees and no separate<br />

<strong>in</strong>dices are provided for younger employees for which sub-m<strong>in</strong>ima may apply<br />

<strong>in</strong> different countries. While the OECD database allows to compare <strong>Europe</strong>an<br />

experiences to non-EU countries with national statutory <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong><br />

(Australia, Canada, Japan, Korea, Mexico, New Zealand, Turkey, and the<br />

United States), it excludes countries <strong>in</strong> which <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> are established<br />

through sector-level collective agreements (such as Germany, Italy, and the<br />

Scand<strong>in</strong>avian countries).<br />

The second source is the <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage data published by Eurostat 3 . This<br />

database is very similar to the OECD <strong>in</strong> that it also conta<strong>in</strong>s <strong>in</strong>formation on<br />

gross levels of national statutory <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> and gross Kaitz <strong>in</strong>dices<br />

(albeit only for monthly rates and only with average earn<strong>in</strong>gs as<br />

denom<strong>in</strong>ator). Moreover, Eurostat also excludes Germany, Italy, Cyprus,<br />

Austria, Switzerland, Iceland, and the Scand<strong>in</strong>avian countries due to the lack<br />

of a national statutory <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage <strong>in</strong> these countries. By contrast,<br />

Eurostat provides data for several Eastern and Central <strong>Europe</strong>an countries<br />

not covered by the OECD (Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta,<br />

Romania, Slovenia, and Croatia). The longitud<strong>in</strong>al coverage of the Eurostat<br />

data is somewhat shorter (1999-2009) compared to the OECD series.<br />

The third <strong>in</strong>ternational source, the ILO M<strong>in</strong>imum Wage Database 4 , is quite<br />

different from the two preced<strong>in</strong>g databases. While the ILO data is less useful<br />

to trace the chronological evolution of statutory <strong>wages</strong> floors and their<br />

relation to average or median earn<strong>in</strong>gs, it conta<strong>in</strong>s valuable qualitative<br />

<strong>in</strong>formation on many features of national <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> systems such as<br />

the national determ<strong>in</strong>ation mechanism, the coverage of exist<strong>in</strong>g <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong><br />

<strong>wages</strong>, adjustment mechanisms, and control and enforcement procedures. In<br />

addition, the ILO provides detailed <strong>in</strong>formation on current levels of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong><br />

2. http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=RHMW<br />

3. http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/statistics_expla<strong>in</strong>ed/<strong>in</strong>dex.php/M<strong>in</strong>imum_wage_statistics<br />

4. http://www.ilo.org/travaildatabase/servlet/<strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong><strong>wages</strong><br />

Report 124<br />

21

François Rycx and Stephan Kampelmann<br />

<strong>wages</strong>, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g exist<strong>in</strong>g sub-m<strong>in</strong>ima. The coverage of the database is much<br />

broader compared to both the OECD and Eurostat: the ILO database <strong>in</strong>cludes<br />

all 100 ILO member countries, i.e. also the countries <strong>in</strong> which <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong><br />

<strong>wages</strong> are set through collective agreements at the sub-national level (such as<br />

<strong>in</strong> Austria, Germany, or Italy). A drawback of the ILO data is that its last<br />

update dates back to September 2006.<br />

Next, the Hans-Böckler-Stiftung ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>s an extensive database on<br />

<strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> 5 via the Wirtschafts- und Sozialwissenschaftliches Institut<br />

(WSI). This database not only monitors the development of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong> Germany tariff sectors, but also provides regular updates on levels of<br />

<strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> for many <strong>Europe</strong>an and non-<strong>Europe</strong>an countries.<br />

F<strong>in</strong>ally, the <strong>Europe</strong>an Industrial Relations Observatory 6 publishes regular<br />

country reports with qualitative <strong>in</strong>formation on labour market <strong>in</strong>stitutions.<br />

These reports typically <strong>in</strong>clude sections on national <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage systems<br />

<strong>in</strong> which the mechanisms for fix<strong>in</strong>g and revis<strong>in</strong>g wage floors are described by<br />

the Observatory's country experts.<br />

In sum, exist<strong>in</strong>g databases conta<strong>in</strong> statistical <strong>in</strong>formation on the bite of<br />

<strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> at the aggregate, national level. At the same time, they have<br />

numerous limitations: they fail to provide statistical <strong>in</strong>formation for countries<br />

with sub-national <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong>; they only conta<strong>in</strong> Kaitz <strong>in</strong>dices that do not<br />

adjust for exist<strong>in</strong>g sub-m<strong>in</strong>ima, the impact of the tax system, or cross-country<br />

differences <strong>in</strong> the composition of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong>-wage earners; and, importantly,<br />

they do not allow to assess neither the employment spike at or near the<br />

<strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage nor the shadow spike that corresponds to hypothetical<br />

<strong>in</strong>creases of the <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage. In other words, these databases are useful to<br />

obta<strong>in</strong> a general impression of cross-country differences regard<strong>in</strong>g the bite of<br />

national statutory <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong>, but they are less apt to further our<br />

understand<strong>in</strong>g of the impact of other types of wage floors. Crucially, they do<br />

not allow to shed light on the characteristics of the affected populations.<br />

As a consequence of these limitations, exist<strong>in</strong>g studies on <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong><br />

earners typically use micro-data from labour force surveys to elucidate<br />

questions such as the size and composition of the employment spike around<br />

the <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage (Dolado et al., 1996; Mach<strong>in</strong> and Mann<strong>in</strong>g, 1997;<br />

<strong>Europe</strong>an Commission, 1998; OECD, 1998; Neumark and Wascher, 2004;<br />

Funk and Lesch, 2006). These studies reveal significant with<strong>in</strong>-country<br />

variation <strong>in</strong> the bite of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong>: Funk and Lesch (2006), for <strong>in</strong>stance,<br />

report that whereas the 2004 <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage <strong>in</strong> Lithuania represented only<br />

38 per cent of average <strong>wages</strong> <strong>in</strong> the economy as a whole, the <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage<br />

<strong>in</strong> the Hotels and Restaurants Sector was as high as 61 per cent of average<br />

<strong>wages</strong> <strong>in</strong> that sector. Similarly, <strong>in</strong> 2004 the Estonian Kaitz <strong>in</strong>dex was 34 per<br />

cent for the entire economy, but 67 per cent <strong>in</strong> the Retail Sector. The bite of<br />

5. A voivodship is an adm<strong>in</strong>istrative unit of the Polish state.<br />

6. http://www.eurofound.europa.eu/eiro/structure.htm<br />

22 Report 124

the <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage also differs accord<strong>in</strong>g to characteristics such as age and<br />

gender. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to the figures <strong>in</strong> OECD (1998), the mid-1997 <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong><br />

wage <strong>in</strong> Belgium represented 49.2 per cent of full-time median earn<strong>in</strong>gs for<br />

men, but as much as 55.2 per cent for women and 66.5 per cent for employees<br />

aged 20-24 years.<br />

What is more, exist<strong>in</strong>g evidence suggests that the share of workers paid at or<br />

near <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage levels differs substantially among <strong>Europe</strong>an countries:<br />

the work force of the Netherlands, Slovenia, Sweden, or Belgium <strong>in</strong>cludes less<br />

than five per cent of <strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> wage earners, whereas this share lies above 10<br />

per cent <strong>in</strong> countries like France, Latvia, Lithuania, and Greece (Dolado et. al,<br />

1996; Funk and Lesch, 2006). Such <strong>in</strong>ternational comparisons are, however,<br />

extremely rare and outdated <strong>in</strong> light of recent developments <strong>in</strong> many<br />

<strong>Europe</strong>an economies. Notably a systematic comparison of the impact of<br />

<strong>m<strong>in</strong>imum</strong> <strong>wages</strong> <strong>in</strong> Western, Central, and Eastern <strong>Europe</strong> is currently not<br />