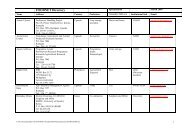

community and household-level income & asset status baseline

community and household-level income & asset status baseline

community and household-level income & asset status baseline

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

irrelevant. On the other h<strong>and</strong>, credit may help farmers to buy technologies that are promoted<br />

by agriculture <strong>and</strong> NRM programs <strong>and</strong> organizations.<br />

Human capital (Education, Sex <strong>and</strong> Age of <strong>household</strong> head)<br />

Education is likely to increase <strong>household</strong>s’ opportunities for salary employment off<br />

farm, <strong>and</strong> may increase their ability to start up various non-farm activities (Barrett, et al.<br />

2001; Deininger <strong>and</strong> Okidi 2001). Education may increase <strong>household</strong>s’ access to credit as<br />

well as their cash <strong>income</strong>, thus helping to finance purchases of <strong>asset</strong>s. Education may also<br />

promote changes in <strong>income</strong> strategies by increasing <strong>household</strong>s’ access to information about<br />

alternative market opportunities <strong>and</strong> technologies, <strong>and</strong> hence <strong>household</strong>s’ ability to adapt to<br />

new opportunities (Feder, et al. 1985). Thus, the impact of education on <strong>household</strong> <strong>income</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>asset</strong> is expected to be positive. However, its impact on participation in programs <strong>and</strong><br />

organizations may be ambiguous since the high opportunity cost of better educated farmers<br />

may not allow them to participate in such activities, or it may increase their need to learn<br />

more about better agricultural production technologies.<br />

Sex of <strong>household</strong> head is an important determinant of <strong>income</strong> since in African setting,<br />

most decisions on investment, location of <strong>household</strong> <strong>and</strong> other major decisions are made by<br />

men. For example, Manundu (1997) observed that women in Kenya are usually not equal partners<br />

when communities create property rights over any resource. It is therefore likely that female-<br />

headed <strong>household</strong>s are likely to be poor, as they will have less access to natural <strong>and</strong> physical<br />

capital. However, it is likely that female-headed <strong>household</strong>s work much harder to compensate<br />

for their disadvantaged position <strong>and</strong> save their hard-earned <strong>income</strong> instead of using it for<br />

buying beer or other luxuries. Hence, it is likely that female-headed <strong>household</strong>s may have<br />

higher <strong>income</strong>.<br />

Impact of gender of <strong>household</strong> head on choice of <strong>income</strong> strategies is likely to be<br />

context specific. For example, women may not choose strategies that require prolonged<br />

10