NOT TO BE PUBLISHED IN OFFICIAL REPORTS IN THE ... - FatWallet

NOT TO BE PUBLISHED IN OFFICIAL REPORTS IN THE ... - FatWallet

NOT TO BE PUBLISHED IN OFFICIAL REPORTS IN THE ... - FatWallet

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Filed 9/30/10 Kershenbaum v. Buy.com CA4/3<br />

<strong>NOT</strong> <strong>TO</strong> <strong>BE</strong> <strong>PUBLISHED</strong> <strong>IN</strong> <strong>OFFICIAL</strong> <strong>REPORTS</strong><br />

California Rules of Court, rule 8.1115(a), prohibits courts and parties from citing or relying on opinions not certified for<br />

publication or ordered published, except as specified by rule 8.1115(b). This opinion has not been certified for publication<br />

or ordered published for purposes of rule 8.1115.<br />

<strong>IN</strong> <strong>THE</strong> COURT OF APPEAL OF <strong>THE</strong> STATE OF CALIFORNIA<br />

RICHARD M. KERSHENBAUM,<br />

Plaintiff and Appellant,<br />

v.<br />

BUY.COM, <strong>IN</strong>C.,<br />

Defendant and Respondent.<br />

FOURTH APPELLATE DISTRICT<br />

DIVISION THREE<br />

G042303<br />

(Super. Ct. No. 07CC01336)<br />

O P I N I O N<br />

Appeal from an order of the Superior Court of Orange County,<br />

Gail Andrea Andler, Judge. Reversed with directions.<br />

Brodsky & Smith, Evan J. Smith; David P. Meyer & Associates Co. and<br />

Matthew R. Wilson for Plaintiff and Appellant.<br />

Rutan & Tucker, Michael T. Hornak, Lisa N. Neal and Zack Broslavsky for<br />

Defendant and Respondent.<br />

* * *

<strong>IN</strong>TRODUCTION<br />

Richard M. Kershenbaum did not receive an advertised rebate on a product<br />

he purchased through Buy.com, Inc.’s Web site. Buy.com contended the rebate was<br />

offered by the product manufacturer, and it was therefore not responsible for<br />

compensating Kershenbaum. Kershenbaum sued Buy.com, and sought class certification<br />

of the lawsuit. The trial court denied the motion, and Kershenbaum appeals. We reverse.<br />

The trial court erred in denying the motion for class certification. The<br />

different definitions of the proposed class contained in the memorandum of points and<br />

authorities and the proposed order did not warrant denial of the motion for lack of<br />

ascertainability. Any confusion caused by the different definitions could and should have<br />

been remedied by the trial court, either by correcting the proposed order, or by<br />

independently drafting a new order.<br />

We further conclude the trial court erred in denying the motion on the<br />

ground that common questions of law did not predominate. The California choice-of-law<br />

provision in Buy.com’s terms of use agreement applies to the claims asserted by the<br />

class. Even if the choice-of-law provision did not apply, class certification was still<br />

appropriate because significant contacts with California have been shown to exist, and<br />

Buy.com cannot demonstrate that any foreign law, rather than California law, should<br />

apply to the class claims.<br />

the class were vague.<br />

We also conclude the trial court erred in determining the claims asserted by<br />

Finally, Kershenbaum had standing to assert a claim for misleading<br />

advertising; the trial court erred in determining otherwise.<br />

STATEMENT OF FACTS AND PROCEDURAL HIS<strong>TO</strong>RY<br />

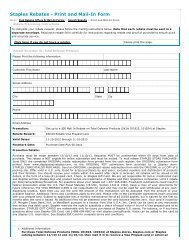

On February 5, 2007, Kershenbaum purchased a Connect 3D memory card<br />

from Buy.com for $30, with a $30 mail-in rebate. Kershenbaum sent in the appropriate<br />

2

ebate forms, and was approved to receive the $30 rebate. Connect 3D, however, failed<br />

to pay the rebate. In July 2007, Buy.com offered those customers who had not received<br />

their rebates a $10 gift certificate.<br />

Kershenbaum filed a class action lawsuit against Buy.com. In his second<br />

amended complaint (which is the operative complaint), Kershenbaum alleged causes of<br />

action against Buy.com for violations of the unfair competition law (Bus. & Prof. Code,<br />

§ 17200 et seq.) (UCL) and the Consumers Legal Remedies Act (Civ. Code, § 1750 et<br />

seq.) (CLRA), and for negligent misrepresentation.<br />

On December 10, 2008, Kershenbaum filed a renewed motion for class<br />

certification. (Kershenbaum’s original motion for class certification was denied without<br />

prejudice for failure to meet his burden of showing an ascertainable class.) The trial<br />

court denied Kershenbaum’s renewed motion for class certification. The court’s order<br />

reads, in relevant part, as follows: “Plaintiff’s Motion for Renewed Class Certification,<br />

assuming it is meant to be a new class certification motion, is denied based on the<br />

following grounds: [] a. Plaintiff presented the Court with three different definitions of<br />

the class. There are two differing definitions in the Points and Authorities . . . and there<br />

is a third definition in the Proposed Order. Therefore, Plaintiff has not proven that there<br />

is an ascertainable class. [] b. Additionally, it is vague as to what claims Plaintiff<br />

asserts against Buy.com: the failure of Buy.com to perform ‘due diligence’ as to Connect<br />

3D’s financial condition, or misleading advertising. [] c. If Plaintiff is asserting<br />

‘misleading advertising,’ i[t] appears the proposed class representative lacks standing, in<br />

that he testified he did not rely on any of Buy.com’s representations or omissions before<br />

purchasing the Connect 3D rebated products. [] d. Plaintiff has not established that<br />

common issues of law predominate.” Kershenbaum timely appealed from the order<br />

denying the motion for class certification.<br />

3

DISCUSSION<br />

I.<br />

STANDARD OF REVIEW AND STANDARDS FOR CLASS CERTIFICATION<br />

“Because trial courts are ideally situated to evaluate the efficiencies and<br />

practicalities of permitting group action, they are afforded great discretion in granting or<br />

denying certification. . . . [I]n the absence of other error, a trial court ruling supported by<br />

substantial evidence generally will not be disturbed ‘unless (1) improper criteria were<br />

used [citation]; or (2) erroneous legal assumptions were made [citation]’ [citation].<br />

Under this standard, an order based upon improper criteria or incorrect assumptions calls<br />

for reversal ‘“even though there may be substantial evidence to support the court’s<br />

order.”’ [Citations.] Accordingly, we must examine the trial court’s reasons for denying<br />

class certification. ‘Any valid pertinent reason stated will be sufficient to uphold the<br />

order.’ [Citation.]” (Linder v. Thrifty Oil Co. (2000) 23 Cal.4th 429, 435-436.)<br />

“‘Code of Civil Procedure section 382 authorizes class suits in California<br />

when “‘the question is one of a common or general interest, of many persons, or when the<br />

parties are numerous, and it is impracticable to bring them all before the court.’ To<br />

obtain certification, a party must establish the existence of both an ascertainable class and<br />

a well-defined community of interest among the class members. [Citations.] The<br />

community of interest requirement involves three factors: ‘(1) predominant common<br />

questions of law or fact; (2) class representatives with claims or defenses typical of the<br />

class; and (3) class representatives who can adequately represent the class.’ [Citation.]”’<br />

[Citation.]” (Kaldenbach v. Mutual of Omaha Life Ins. Co. (2009) 178 Cal.App.4th 830,<br />

843.) As the moving party, Kershenbaum bore the burden of proving all the elements for<br />

class certification. (Richmond v. Dart Industries, Inc. (1981) 29 Cal.3d 462, 470.)<br />

4

II.<br />

IS <strong>THE</strong> CLASS ASCERTA<strong>IN</strong>ABLE?<br />

The trial court found the class was not ascertainable because Kershenbaum<br />

had offered multiple definitions of the class in his motion papers: “Plaintiff presented the<br />

Court with three different definitions of the class. There are two differing definitions in<br />

the Points and Authorities . . . and there is a third definition in the Proposed Order.<br />

Therefore, Plaintiff has not proven that there is an ascertainable class.” The<br />

memorandum of points and authorities in support of the renewed motion for class<br />

certification defined the proposed class as follows: “All persons in the United States who<br />

purchased a Connect 3D product from Defendant Buy.com, Inc. (‘Buy.com’) that<br />

included a rebate offer and whose rebate submissions were approved for payment. []<br />

Excluded from the Class are the Court, Defendant, its affiliates, employees, officers and<br />

directors, and anyone who was paid his or her rebate by Buy.com.” (Fn. omitted.) 1 The<br />

proposed order, however, defined the proposed class as follows: “All persons in the<br />

United States who purchased a Connect 3D product (including Hannspree products) from<br />

Defendant Buy.com, Inc. (‘Buy.com’) that included a rebate offer and whose rebate<br />

submissions were approved for payment. Excluded from the Class are the Court,<br />

Defendant, its affiliates, employees, officers and directors, and anyone who was paid his<br />

or her rebate by Buy.com.” (Italics added.) Nowhere in the renewed motion for class<br />

certification are Hannspree products mentioned.<br />

Kershenbaum’s appellate briefs simply ignore this issue on which the trial<br />

court based its order denying class certification. Kershenbaum merely reiterates that<br />

1 The other definition of the class in the memorandum of points and authorities<br />

reads: “All persons in the United States who purchased a Connect 3D product from<br />

Buy.com that included a rebate offer and whose rebate submissions were approved for<br />

payment. [] Excluded from the Class are the Court, Defendant, its affiliates, employees,<br />

officers and directors, and anyone who was paid his or her rebate by Buy.com.” These<br />

definitions are not appreciably different. To conclude the class was not ascertainable<br />

based on these two different definitions clearly constitutes an abuse of discretion.<br />

5

Buy.com has all the necessary information about the individuals who purchased<br />

“Connect3D rebate eligible products.” The problem is that Kershenbaum never states<br />

whether the purchasers of Hannspree products are within this group. 2 “‘Ascertainability<br />

is required in order to give notice to putative class members as to whom the judgment in<br />

the action will be res judicata.’ [Citations.] The representative plaintiff need not identify<br />

the individual members of the class at the class certification stage in order for the class<br />

members to be bound by the judgment. [Citation.] As long as the potential class<br />

members may be identified without unreasonable expense or time and given notice of the<br />

litigation, and the proposed class definition offers an objective means of identifying those<br />

persons who will be bound by the results of the litigation, the ascertainability requirement<br />

is met.” (Medrazo v. Honda of North Hollywood (2008) 166 Cal.App.4th 89, 101.)<br />

Kershenbaum argues that even if the class was not adequately defined, the<br />

trial court had the discretion to redefine the class, quoting from Hicks v. Kaufman &<br />

Broad Home Corp. (2001) 89 Cal.App.4th 908, 916: “Furthermore, if necessary to<br />

preserve the case as a class action, the court itself can and should redefine the class where<br />

the evidence before it shows such a redefined class would be ascertainable.” Although<br />

Kershenbaum does not state it explicitly, presumably he means to argue that the trial<br />

court should have removed the reference to Hannspree products from the class definition<br />

in the proposed order.<br />

2 At oral argument, Kershenbaum’s counsel advised the court that the inclusion of<br />

the reference to Hannspree products in the proposed order was intended to avoid<br />

confusion about the scope of the class. Specifically, counsel stated that six products sold<br />

by Connect 3D were subject to rebates which were never paid; four of those products<br />

were sold under the Connect 3D name, while the other two were sold under the<br />

Hannspree name. Counsel could not, however, explain why the memorandum of points<br />

and authorities did not also contain that language, speculating that the differing language<br />

was the result of a “scrivener’s error.” Counsel conceded that by failing to ensure the<br />

language of all the related documents contained the same definition, he caused far more<br />

confusion than he prevented.<br />

6

We agree with Kershenbaum that the class was defined in the memorandum<br />

of points and authorities and the court’s reason for denying the motion was legally<br />

erroneous. The trial court did not find anything in that definition that made the class<br />

unascertainable. If the definition of the class contained in the proposed order did not<br />

match that in the memorandum of points and authorities, the trial court could have<br />

deleted the Hannspree reference from the proposed order, directed the prevailing party to<br />

draft an order consistent with the court’s ruling, or drafted its own order. In failing to do<br />

so, and instead denying the renewed motion for class certification for an improper reason,<br />

the court erred. We reverse the order; the trial court is directed to issue a new order<br />

finding ascertainability of a class defined in its discretion. The trial court has the<br />

discretion to order additional briefing and a hearing in order to do so.<br />

Buy.com also notes that the proposed class definition did not account for<br />

the CLRA’s limitation to consumers. This argument was not raised in the trial court.<br />

Even if we were to consider it, it does not affect our opinion.<br />

Kershenbaum does not dispute that the CLRA claim may only provide<br />

relief to those proposed class members who bought products for consumer use, not to<br />

those who bought products for commercial use. (See Civ. Code, § 1761, subd. (d) [as<br />

used in the CLRA, a consumer is “an individual who seeks or acquires, by purchase or<br />

lease, any goods or services for personal, family, or household purposes”]; id., § 1780,<br />

subd. (a) [“Any consumer who suffers any damage as a result of the use or employment<br />

by any person of a method, act, or practice declared to be unlawful by Section 1770 may<br />

bring an action against that person”].) Instead, Kershenbaum asserts, without any factual<br />

support, that the products purchased by the proposed class in this case—memory cards<br />

and televisions—“are no more likely to be purchased for business purposes than cars or<br />

other vehicles,” which were the products purchased in other cases where the courts<br />

granted class certification.<br />

7

In Lazar v. Hertz Corp. (1983) 143 Cal.App.3d 128, 136, the plaintiff filed<br />

a class action lawsuit against Hertz Corporation for violation of the CLRA, among other<br />

claims, for charging outrageous sums to refuel rental cars which were returned unfilled.<br />

The plaintiff conceded he did not rent a car from Hertz as a consumer, and was therefore<br />

not a member of the proposed class. (Lazar v. Hertz Corp., supra, at p. 142.) The<br />

appellate court reversed the trial court’s denial of a motion for class certification,<br />

concluding in part that although the plaintiff could not represent the class, the case could<br />

proceed as a class action with a new consumer plaintiff being permitted to intervene.<br />

(Ibid.) Under the rule of Lazar v. Hertz Corp. (which was not cited or discussed by<br />

Buy.com), a class may be certified for a case including a CLRA claim even though some<br />

of the members of the class are not consumers. 3<br />

III.<br />

DO COMMON QUESTIONS OF LAW PREDOM<strong>IN</strong>ATE?<br />

The trial court also denied the motion for class certification on the ground<br />

that Kershenbaum had failed to establish common issues of law predominate. Buy.com<br />

contends that because the class members are residents of all 50 states, and California law<br />

regarding consumer protection claims differs materially from the laws of other states,<br />

differences in the law to be applied to the UCL and CLRA claims will “swamp” the<br />

common issues, making class certification inappropriate.<br />

3 Kershenbaum also cites Lewis v. Robinson Ford Sales, Inc. (2007) 156<br />

Cal.App.4th 359 and Medrazo v. Honda of North Hollywood, supra, 166 Cal.App.4th 89,<br />

for the proposition that a case involving CLRA claims may be certified as a class action.<br />

In both cases, which involved sales of motorcycles or other vehicles, some members of<br />

the proposed classes may have intended to use the vehicles for commercial, not consumer<br />

or household, purposes, and therefore could not properly be a part of a class asserting a<br />

CLRA claim. In both cases, the appellate court reversed the order denying class<br />

certification. In neither case, however, was the issue of the limitation of CLRA claims to<br />

consumer plaintiffs raised. A judicial decision is not authority for a point that was not<br />

raised and resolved. (Fairbanks v. Superior Court (2009) 46 Cal.4th 56, 64.)<br />

8

To determine whether the trial court abused its discretion in finding<br />

common issues of law did not predominate, we consider whether a choice-of-law<br />

provision applies, and if not, how to determine what law applies when violations of<br />

California consumer protection laws are alleged in a case involving a potential<br />

nationwide class. 4<br />

The parties dispute whether an enforceable choice-of-law agreement exists<br />

in this case. Buy.com’s Web site contains a choice-of-law provision in its terms of use<br />

agreement: “This Terms of Use shall be governed by the laws of the State of California<br />

without regard to or application of any conflict of laws provisions.” Buy.com argues<br />

Kershenbaum’s claims do not arise out of the terms of use agreement, and therefore the<br />

contractual choice-of-law provision does not apply. The terms of use agreement<br />

provides: “READ CAREFULLY. This Terms of Use Agreement (‘Terms of Use’)<br />

applies to use of the Buy.com website located at http://www.buy.com (the ‘Site’). The<br />

Site is the property of Buy.com Inc. (together with its affiliated companies, including<br />

without limitation, BuyMusic.com Inc. and BuyServices Inc., ‘Buy.com’). Before you<br />

make any purchases, you must first establish a customer account (‘My Account’). BY<br />

CLICK<strong>IN</strong>G ‘I HAVE READ, UNDERSTAND AND AGREE <strong>TO</strong> <strong>THE</strong> TERMS OF<br />

USE,’ YOU AGREE <strong>TO</strong> <strong>THE</strong>SE TERMS OF USE. IF YOU DO <strong>NOT</strong> AGREE, DO<br />

<strong>NOT</strong> CLICK ON <strong>THE</strong> BUT<strong>TO</strong>N AND DO <strong>NOT</strong> USE <strong>THE</strong> SITE.” (Boldface omitted.) 5<br />

Buy.com concedes in its brief on appeal that the choice-of-law provision in<br />

the terms of use agreement would apply to “all causes of action arising from or related to<br />

4 California law applies when a California court is asked to consider the<br />

applicability of a choice-of-law provision, whether that provision elects California law or<br />

a foreign state’s law. (Discover Bank v. Superior Court (2005) 134 Cal.App.4th 886,<br />

890-891.)<br />

5 At oral argument, Buy.com’s counsel compared the choice-of-law provision in<br />

Buy.com’s terms of use agreement to that in the Amazon.com terms of use agreement,<br />

arguing Amazon’s provision is much broader. The terms of use agreements of other<br />

online retailers are not in the appellate record, and are not properly before us.<br />

9

that agreement, regardless of how they are characterized, including tortious breaches of<br />

duties emanating from the agreement or the legal relationships it creates.” (Nedlloyd<br />

Lines B.V. v. Superior Court (1992) 3 Cal.4th 459, 470 (Nedlloyd Lines).) At root, the<br />

allegations in Kershenbaum’s second amended complaint are that Buy.com made<br />

negligent misrepresentations on its Web site inducing the potential class members to<br />

make purchases of Connect 3D products through the Buy.com Web site. Kershenbaum’s<br />

claims arise from or are related to the agreement governing the use of the Buy.com Web<br />

site. Therefore, we conclude the choice-of-law provision covers Kershenbaum’s claims. 6<br />

Regarding contractual choice-of-law provisions, the Restatement Second of<br />

Conflict of Laws, section 187, subdivision (2), provides: “The law of the state chosen by<br />

the parties to govern their contractual rights and duties will be applied, even if the<br />

particular issue is one which the parties could not have resolved by an explicit provision<br />

in their agreement directed to that issue, unless either [] (a) the chosen state has no<br />

substantial relationship to the parties or the transaction and there is no other reasonable<br />

basis for the parties’ choice, or [] (b) application of the law of the chosen state would be<br />

contrary to a fundamental policy of a state which has a materially greater interest than the<br />

chosen state in the determination of the particular issue and which, under the rule of<br />

§ 188, would be the state of the applicable law in the absence of an effective choice of<br />

law by the parties.” Application of Restatement Second of Conflict of Laws, section 187,<br />

subdivision (2), on this issue has been approved by the California Supreme Court. (See<br />

Nedlloyd Lines, supra, 3 Cal.4th at pp. 464-465.)<br />

6 Buy.com focuses on Kershenbaum’s claim, as asserted in response to Buy.com’s<br />

motion for summary adjudication, that Buy.com failed to conduct due diligence on<br />

Connect 3D. The distinction between the ways Kershenbaum has asserted his claims is<br />

relevant to our analysis of the trial court’s finding that the claims are vague, discussed<br />

post. It is not relevant to the present discussion of whether the choice-of-law provision<br />

applies to Kershenbaum’s claims.<br />

10

The California choice-of-law provision in Buy.com’s terms of use<br />

agreement applies in this case. California has a substantial relationship to the parties and<br />

the transaction; Buy.com is based in California, and all the transactions in question were<br />

processed by Buy.com. Additionally, no other state has a materially greater interest than<br />

California in the resolution of this case.<br />

Buy.com’s terms of use agreement constitutes a contract of adhesion.<br />

Choice-of-law provisions included in adhesion contracts are enforceable “where they are<br />

otherwise appropriate.” (Washington Mutual Bank v. Superior Court (2001) 24<br />

Cal.4th 906, 917 (Washington Mutual).) The analysis of Nedlloyd Lines and Restatement<br />

Second of Conflict of Laws, section 187, subdivision (2), permits the weaker party to an<br />

adhesion contract to argue that substantial injustice would result from enforcing the<br />

choice-of-law provision, or that the contract was imposed through the unfair use of<br />

superior bargaining power. (Washington Mutual, supra, at p. 918.) Here, however, it is<br />

not the party with the weaker bargaining power that is arguing against the use of the<br />

choice-of-law provision contained in the parties’ contract—it is the party that drafted the<br />

choice-of-law provision and made it a part of its Web site’s terms of use agreement,<br />

without the acceptance of which no other party could purchase goods through the<br />

Web site.<br />

Both Kershenbaum and Buy.com rely on the California Supreme Court’s<br />

analysis in Washington Mutual. In that case, a borrower sued her lender for, among other<br />

things, violating the UCL by purchasing expensive replacement insurance when the<br />

borrowers defaulted on their loan obligation of maintaining hazard insurance.<br />

(Washington Mutual, supra, 24 Cal.4th at p. 912.) The loan documents contained a<br />

choice-of-law provision making federal law and the law of the state in which the secured<br />

property was located applicable. (Ibid.) The trial court certified a nationwide class<br />

without deciding what law would apply to the class members’ claims. (Id. at p. 913.)<br />

The Supreme Court reversed the certification order, due to its incomplete and erroneous<br />

11

analysis of the factors relevant to certification: “[W]e hold that a class action proponent<br />

must credibly demonstrate, through a thorough analysis of the applicable state laws, that<br />

state law variations will not swamp common issues and defeat predominance.<br />

Additionally, the proponent’s presentation must be sufficient to permit the trial court, at<br />

the time of certification, to make a detailed assessment of how any state law differences<br />

could be managed fairly and efficiently at trial, for example, through the creation of a<br />

manageable number of subclasses. Trial courts, in assessing the propriety of nationwide<br />

class certification, must consider these factors, as well as all the other factors relevant to<br />

certification, including the potential recovery of each individual claimant and whether the<br />

proposed class suit is the only effective way to redress the alleged wrongdoing or to<br />

prevent unjust advantage to the defendant. [Citations.] Adherence to these procedures<br />

should ensure that nationwide class actions are certified only where they will result in<br />

substantial benefits both to the litigants and the courts. [Citation.]” (Id. at p. 926,<br />

fn. omitted.)<br />

The analysis of Washington Mutual applies when there is an enforceable<br />

choice-of-law agreement selecting the law of one or more other states, and the<br />

challenging party asks the California courts to apply the foreign law. (Wershba v. Apple<br />

Computer, Inc. (2001) 91 Cal.App.4th 224, 244 (Wershba).) Washington Mutual is not<br />

applicable in the present case because the choice-of-law provision selected California<br />

law. Indeed, the questions answered by the Supreme Court in Washington Mutual, supra,<br />

24 Cal.4th at page 914, are as follows: “First, what is the appropriate analysis for<br />

selecting applicable law in a class action where putative class members have<br />

contractually agreed to application of another state’s law? Second, what analysis must be<br />

undertaken in the event litigation of the class action will necessitate application of the<br />

laws of multiple states?” For the reasons we have explained, neither of these questions is<br />

implicated here because the parties chose California law as the applicable law.<br />

12

Even if Buy.com were correct, and the California choice-of-law provision<br />

did not apply to Kershenbaum’s claims, the relevant analysis would compel the same<br />

conclusion. Where there is no enforceable choice-of-law agreement, “[s]o long as the<br />

requisite significant contacts with California are shown to exist, sufficient to meet<br />

constitutional standards, the burden is on the parties challenging the nationwide<br />

certification to demonstrate that ‘foreign law, rather than California law, should apply to<br />

class claims.’ [Citation.]” (Wershba, supra, 91 Cal.App.4th at p. 244.)<br />

“‘Analysis of a choice of law question proceeds in three steps:<br />

(1) determination of whether the potentially concerned states have different laws,<br />

(2) consideration of whether each of the states has an interest in having its law applied to<br />

the case, and (3) if the laws are different and each has an interest in having its law<br />

applied (a “true” conflict), selection of which state’s law to apply by determining which<br />

state’s interests would be more impaired if its policy were subordinated to the policy of<br />

the other state. [Citations.]’ [Citation.]” (Clothesrigger, Inc. v. GTE Corp. (1987) 191<br />

Cal.App.3d 605, 614.)<br />

In Wershba, supra, 91 Cal.App.4th at page 230, a case where there was no<br />

choice-of-law provision, a California-based computer manufacturer changed its policy of<br />

providing free technical support, and immediately began requiring its customers to pay<br />

for technical support. Several class action lawsuits raising claims for breach of contract<br />

and violations of the UCL and the CLRA were filed. (Wershba, supra, at p. 231.) A<br />

nationwide class was certified at the same time a proposed settlement was preliminarily<br />

approved by the trial court. (Id. at p. 232.) Objections to the proposed settlement were<br />

filed, in part objecting because the state law consumer claims should not be pursued by a<br />

nationwide class. (Id. at pp. 233-234.) The trial court rejected the objections, certified<br />

the nationwide class, and approved the settlement. (Id. at p. 234.)<br />

13

On appeal, the appellate court concluded it was appropriate to certify a<br />

nationwide class to pursue the claims for violations of the UCL and the CLRA: “[A]<br />

California court may properly apply the same California statutes at issue here to<br />

non-California members of a nationwide class where the defendant is a California<br />

corporation and some or all of the challenged conduct emanates from California.<br />

[Citations.]” (Wershba, supra, 91 Cal.App.4th at p. 243.) “Even though there may be<br />

differences in consumer protection laws from state to state, this is not necessarily fatal to<br />

a finding that there is a predominance of common issues among a nationwide class. As<br />

the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals has observed, state consumer protection laws are<br />

relatively homogeneous: ‘the idiosyncratic differences between state consumer<br />

protection laws are not sufficiently substantive to predominate over the shared claims’<br />

and do not preclude certification of a nationwide settlement class.” (Id. at p. 244.)<br />

Although the trial court in the present case was not considering a settlement class, we do<br />

not find that dispositive, especially because “California’s consumer protection laws are<br />

among the strongest in the country.” (Id. at p. 242.)<br />

Here, Buy.com is headquartered in California. The allegedly misleading<br />

rebate information on Buy.com’s Web site originated from California. The due diligence<br />

Buy.com allegedly failed to perform would have been performed in California. This state<br />

has a clear connection to the claims asserted by Kershenbaum. Although there are<br />

differences between the consumer protection laws of California and those of other states,<br />

those differences generally favor the consumers, and Buy.com cannot explain why<br />

another state would object to having California provide greater protection to its citizens<br />

against alleged wrongdoing by a California defendant.<br />

Under Wershba and Clothesrigger, Inc. v. GTE Corp., even if the<br />

California choice-of-law provision in Buy.com’s terms of use agreement did not apply,<br />

the trial court erred in finding common issues did not predominate.<br />

14

IV.<br />

ARE <strong>THE</strong> CLAIMS VAGUE?<br />

The trial court also denied Kershenbaum’s motion for class certification<br />

because “it is vague as to what claims Plaintiff asserts against Buy.com: the failure of<br />

Buy.com to perform ‘due diligence’ as to Connect 3D’s financial condition, or<br />

misleading advertising.”<br />

Kershenbaum’s argument on appeal regarding this issue is as follows:<br />

“The Trial Court stated that it was unclear whether Appellant sought a class to be<br />

certified based on its claim involving ‘due diligence’ or on ‘misleading advertising.’ But<br />

that is a false dichotomy. Appellant’s claim is that Buy.com performed inadequate due<br />

diligence, and as a result, it advertise[d] that rebates were available when they were not –<br />

and that advertising was, in fact, misleading (indeed, it was utterly false, since no one in<br />

the putative class was paid their rebates).”<br />

The reply brief, for the most part, repeats the opening brief’s argument:<br />

“Buy.com contends that Mr. Kershenbaum is vague as to what claims he asserts against<br />

Buy.com: due diligence or misleading advertising. . . . But that is a false dichotomy.<br />

Buy.com advertised that rebates were available when they were not – and that advertising<br />

was, in fact, misleading (indeed, it was utterly false, since no one in the putative class<br />

was paid his or her rebate). It was negligent for Buy.com to have made such<br />

misrepresentations, because, Mr. Kershenbaum alleges, it virtually took Connect 3D’s<br />

word for it that Connect 3D would be good for the rebates. The misrepresentations at<br />

issue are the ones every single person in the putative class must have seen and relied<br />

upon: that a rebate was available with the Connect 3D products.” (Original italics.)<br />

Although Kershenbaum’s pleadings could have been clearer, his allegations<br />

were not so vague as to warrant denial of his motion for class certification. Accordingly,<br />

we conclude the trial court erred in denying the class certification motion on the ground<br />

that it was vague whether Kershenbaum was arguing that Buy.com failed to conduct due<br />

15

diligence on Connect 3D, or that Buy.com’s Web site stating Connect 3D’s products<br />

were free after the rebate was misleading advertising. In essence, Kershenbaum alleged<br />

the advertising of a free rebate was misleading.<br />

V.<br />

DOES <strong>THE</strong> PROPOSED CLASS REPRESENTATIVE HAVE STAND<strong>IN</strong>G<br />

FOR <strong>THE</strong> MISLEAD<strong>IN</strong>G ADVERTIS<strong>IN</strong>G CLAIM?<br />

The trial court also found that Kershenbaum did not have standing to assert<br />

a claim for misleading advertising. “If Plaintiff is asserting ‘misleading advertising,’ i[t]<br />

appears the proposed class representative lacks standing, in that he testified he did not<br />

rely on any of Buy.com’s representations or omissions before purchasing the Connect 3D<br />

rebated products.” At his deposition, Kershenbaum testified that he believed an online<br />

retailer should always be responsible for paying the advertised rebate on products it sells<br />

through its Web site, even if the Web site states the rebate will be provided by the<br />

manufacturer, not the online retailer. Buy.com therefore argues Kershenbaum did not<br />

rely on any misrepresentations or omissions because “[t]here was thus nothing Buy.com<br />

could have done to prevent Kershenbaum from thinking that Buy.com was responsible<br />

for the Connect 3D rebates, not even if Buy.com had conducted an independent audit or<br />

provided an express disclaimer.” (Boldface omitted.)<br />

The misleading advertising Kershenbaum’s complaint alleged is the<br />

statement that the Connect 3D products purchased were free after the rebate, when in fact<br />

a rebate was not available. Kershenbaum has standing to assert such a claim, and the trial<br />

court erred in determining otherwise. We take no position as to the merits of<br />

Kershenbaum’s claim.<br />

16

DISPOSITION<br />

The order is reversed. The trial court is directed to enter an order certifying<br />

a class, the definition of which shall be in the trial court’s discretion. Appellant to<br />

recover costs on appeal.<br />

WE CONCUR:<br />

O’LEARY, ACT<strong>IN</strong>G P. J.<br />

IKOLA, J.<br />

17<br />

FY<strong>BE</strong>L, J.