1 Understanding food insecurity in rural Rwanda: how women ...

1 Understanding food insecurity in rural Rwanda: how women ...

1 Understanding food insecurity in rural Rwanda: how women ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

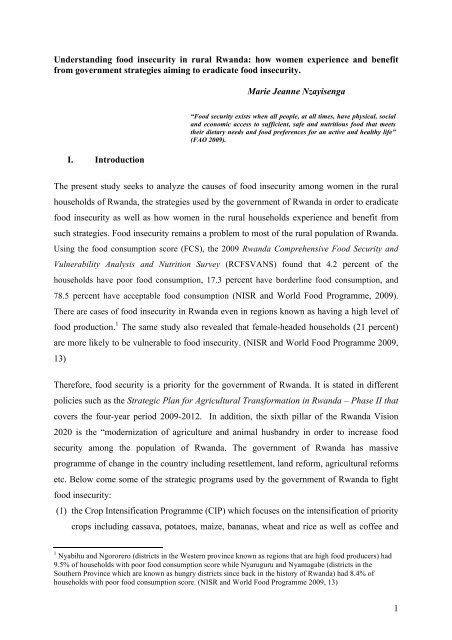

<strong>Understand<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>food</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>security</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>rural</strong> <strong>Rwanda</strong>: <strong>how</strong> <strong>women</strong> experience and benefit<br />

from government strategies aim<strong>in</strong>g to eradicate <strong>food</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>security</strong>.<br />

Marie Jeanne Nzayisenga<br />

I. Introduction<br />

“Food security exists when all people, at all times, have physical, social<br />

and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious <strong>food</strong> that meets<br />

their dietary needs and <strong>food</strong> preferences for an active and healthy life”<br />

(FAO 2009).<br />

The present study seeks to analyze the causes of <strong>food</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>security</strong> among <strong>women</strong> <strong>in</strong> the <strong>rural</strong><br />

households of <strong>Rwanda</strong>, the strategies used by the government of <strong>Rwanda</strong> <strong>in</strong> order to eradicate<br />

<strong>food</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>security</strong> as well as <strong>how</strong> <strong>women</strong> <strong>in</strong> the <strong>rural</strong> households experience and benefit from<br />

such strategies. Food <strong><strong>in</strong>security</strong> rema<strong>in</strong>s a problem to most of the <strong>rural</strong> population of <strong>Rwanda</strong>.<br />

Us<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>food</strong> consumption score (FCS), the 2009 <strong>Rwanda</strong> Comprehensive Food Security and<br />

Vulnerability Analysis and Nutrition Survey (RCFSVANS) found that 4.2 percent of the<br />

households have poor <strong>food</strong> consumption, 17.3 percent have borderl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>food</strong> consumption, and<br />

78.5 percent have acceptable <strong>food</strong> consumption (NISR and World Food Programme, 2009).<br />

There are cases of <strong>food</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>security</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Rwanda</strong> even <strong>in</strong> regions known as hav<strong>in</strong>g a high level of<br />

<strong>food</strong> production. 1 The same study also revealed that female-headed households (21 percent)<br />

are more likely to be vulnerable to <strong>food</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>security</strong>. (NISR and World Food Programme 2009,<br />

13)<br />

Therefore, <strong>food</strong> security is a priority for the government of <strong>Rwanda</strong>. It is stated <strong>in</strong> different<br />

policies such as the Strategic Plan for Agricultural Transformation <strong>in</strong> <strong>Rwanda</strong> – Phase II that<br />

covers the four-year period 2009-2012. In addition, the sixth pillar of the <strong>Rwanda</strong> Vision<br />

2020 is the “modernization of agriculture and animal husbandry <strong>in</strong> order to <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>food</strong><br />

security among the population of <strong>Rwanda</strong>. The government of <strong>Rwanda</strong> has massive<br />

programme of change <strong>in</strong> the country <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g resettlement, land reform, agricultural reforms<br />

etc. Below come some of the strategic programs used by the government of <strong>Rwanda</strong> to fight<br />

<strong>food</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>security</strong>:<br />

(1) the Crop Intensification Programme (CIP) which focuses on the <strong>in</strong>tensification of priority<br />

crops <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g cassava, potatoes, maize, bananas, wheat and rice as well as coffee and<br />

1 Nyabihu and Ngororero (districts <strong>in</strong> the Western prov<strong>in</strong>ce known as regions that are high <strong>food</strong> producers) had<br />

9.5% of households with poor <strong>food</strong> consumption score while Nyaruguru and Nyamagabe (districts <strong>in</strong> the<br />

Southern Prov<strong>in</strong>ce which are known as hungry districts s<strong>in</strong>ce back <strong>in</strong> the history of <strong>Rwanda</strong>) had 8.4% of<br />

households with poor <strong>food</strong> consumption score. (NISR and World Food Programme 2009, 13)<br />

1

tea as the two ma<strong>in</strong> cash crops <strong>in</strong> <strong>Rwanda</strong>. The programme <strong>in</strong>tends to <strong>in</strong>crease<br />

agricultural production by distribut<strong>in</strong>g fertilizers and seeds to farmers.(Republic of<br />

<strong>Rwanda</strong> 2010, 18-19)<br />

(2) Households <strong>in</strong> the <strong>rural</strong> areas are obliged to have a vegetable garden.<br />

(3) The one cow per family that consists <strong>in</strong> distribut<strong>in</strong>g cows to poor households because<br />

livestock play an important role <strong>in</strong> <strong>food</strong> security by provid<strong>in</strong>g animal products rich <strong>in</strong><br />

prote<strong>in</strong>, provid<strong>in</strong>g manure, and it is a significant source of <strong>in</strong>come for small holders<br />

(Republic of <strong>Rwanda</strong> 2006, 5).<br />

Although multiple measures have been taken at national and <strong>in</strong>ternational level, <strong>food</strong><br />

<strong><strong>in</strong>security</strong> is a complex issue <strong>in</strong> that it is driven by trends such as population growth and<br />

urbanization, rises <strong>in</strong> <strong>food</strong> prices, a global economic crisis, chang<strong>in</strong>g diets and <strong>food</strong><br />

consumption patterns, processes such as environmental and climate change (Brown 2009;<br />

P<strong>in</strong>strup-Andersen 2007; Smill 2000; cited <strong>in</strong> McDonald 2010, 5). The complexity of these<br />

driv<strong>in</strong>g forces have led many analysts to conclude that the world faces a significant set of<br />

challenges <strong>in</strong> the com<strong>in</strong>g years as impacts of climate change, population growth, water<br />

scarcity, and energy shortages will all contribute to and magnify the impacts of <strong>food</strong><br />

<strong><strong>in</strong>security</strong> (Bedd<strong>in</strong>gton 2009).<br />

One of the challenges of <strong>food</strong> security studies is the common tendency <strong>in</strong> such studies to<br />

focus on <strong>food</strong> production rather than other components of people’s provision<strong>in</strong>g strategies<br />

(Liwenga 2003). The consequence of that is that a sole focus on production obscures the<br />

range of livelihood strategies that work together with <strong>food</strong> production <strong>in</strong> order to ensure <strong>food</strong><br />

security (Cornwall and Scoones 1993, 68). A livelihood strategy encompasses not only<br />

activities that generate <strong>in</strong>come, but many other k<strong>in</strong>ds of choices, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g cultural and social<br />

choices, that come together to make up the primary occupation of a household (Ellis, 1998).<br />

Periodic or chronic <strong>food</strong> stress does not cause all members of a population to be similarly or<br />

equally affected. As Van Andel (1998) says, the <strong>rural</strong> household is not a homogenous group<br />

of <strong>in</strong>dividuals hence the importance of dist<strong>in</strong>guish<strong>in</strong>g not only households’ types, but also<br />

<strong>in</strong>dividuals with<strong>in</strong> households when consider<strong>in</strong>g factors such as access to resources and<br />

livelihood issues (Guyer 1980; Moock 1986).<br />

The present research proposal consists of the follow<strong>in</strong>g ma<strong>in</strong> parts: the first part is the<br />

<strong>in</strong>troduction that discusses briefly the work and motivation of why <strong>Rwanda</strong> is a relevant case<br />

and <strong>how</strong> <strong>food</strong> security is a priority for the government of <strong>Rwanda</strong>; the second part is about the<br />

2

esearch problems, the third part consists of the theoretical departure po<strong>in</strong>ts and it discusses<br />

security as a broad concept, human security, gender and security, <strong>food</strong> security(its<br />

dimensions, the social aspect of <strong>food</strong> security, the role of the <strong>in</strong>ternational community and<br />

local governments <strong>in</strong> <strong>food</strong> security); the last part discusses the research design, <strong>how</strong> the<br />

questions will be answered, who will participate <strong>in</strong> the study, where the study will be<br />

conducted, ethical considerations, and the time plan.<br />

II.<br />

<strong>Rwanda</strong> as a case<br />

The 2006 Comprehensive Food Security and Vulnerability Analysis revealed that 52 percent<br />

of households <strong>in</strong> <strong>Rwanda</strong> are <strong>food</strong> <strong>in</strong>secure or vulnerable and among them 43 percent are<br />

concentrated <strong>in</strong> <strong>rural</strong> areas. Although <strong>food</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>security</strong> is found all over the country, it tends to<br />

be concentrated <strong>in</strong> the Western and Southern prov<strong>in</strong>ces and it is highest among agricultural<br />

labourers and those with ‘marg<strong>in</strong>al livelihoods’ <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g those dependent on social transfers<br />

and female-headed households (NISR and World Food Programme, 2006). Read<strong>in</strong>g from<br />

policy documents such as the Economic Development and Poverty Reduction Strategy<br />

(EDPRS) 2007, most vulnerable households <strong>in</strong> <strong>Rwanda</strong> are headed by <strong>women</strong>, widows and<br />

children and they represent 43 percent of all households (EDPRS 2007, 17)<br />

After the genocide <strong>women</strong> comprised 70 percent of <strong>Rwanda</strong>’s population s<strong>in</strong>ce men who<br />

usually had been the breadw<strong>in</strong>ner of their families were either deceased or disappeared<br />

(Sch<strong>in</strong>dler 2010). This created a vacuum and <strong>women</strong> started to take breadw<strong>in</strong>ner role<br />

cultivat<strong>in</strong>g their lands. In 2008, <strong>women</strong> were 52 percent of the population of <strong>Rwanda</strong>, they<br />

headed 32 percent of the home, and they have become a productive segment of the<br />

population. However, after the war <strong>food</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>security</strong> amongst <strong>rural</strong> <strong>women</strong> and children<br />

cont<strong>in</strong>ue to elevate threaten<strong>in</strong>g the development of <strong>rural</strong> populations who are also vulnerable<br />

to diseases. In addition, research on <strong>Rwanda</strong> has revealed that <strong>women</strong> are more vulnerable to<br />

poverty and <strong>food</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>security</strong>. For example, Ansoms and McKay (2010, 588) dist<strong>in</strong>guished<br />

seven clusters of the population of <strong>Rwanda</strong> depend<strong>in</strong>g on their livelihood and they found that<br />

the bottom cluster is made of female-headed households, <strong>in</strong> most cases headed by older<br />

<strong>women</strong>. The human resources of this cluster are very limited <strong>in</strong> terms of the number of adults<br />

<strong>in</strong> the households hav<strong>in</strong>g an <strong>in</strong>come, the education level of the households and the average<br />

land available for cultivation. In terms of livestock, female-headed households are seriously<br />

deprived.<br />

3

The factors contribut<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>food</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>security</strong> are numerous: dry spells, too much ra<strong>in</strong>fall, crop<br />

pests, oversell<strong>in</strong>g of crops dur<strong>in</strong>g fam<strong>in</strong>es, human diseases such as cholera, population<br />

growth, demographic change, the vast gap between the rich and the poor, climate change,<br />

global <strong>food</strong> price on rise, impacts of new technologies on agriculture and <strong>food</strong> production<br />

<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g low <strong>food</strong> production as well as challenges such as poverty, governance and trade<br />

issues (Liwenga 2003, 58; McDonald 2010, 54-56; NISR and World Food Programme 2009).<br />

However, households’ responses to <strong>food</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>security</strong> vary and they are often differentiated by<br />

socio-economic factors such as wealth and gender and this determ<strong>in</strong>es a range of cop<strong>in</strong>g<br />

options at the household’s disposal (Toulm<strong>in</strong>, 1986). This argument is supported by Pottier<br />

(1993, 68) who argues that periodic or chronic <strong>food</strong> stress does not cause all members of a<br />

population to be similarly or equally affected.<br />

The <strong>Rwanda</strong>n case is highly relevant to study due to a number of factors: (a) <strong>Rwanda</strong> is<br />

recover<strong>in</strong>g from very extreme violence/genocide, (b) the <strong>Rwanda</strong>n government has launched<br />

extremely ambitious programmes to rebuild the country, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g programmes related to<br />

agriculture, resettlement and poverty alleviations, all of which have major implications for the<br />

<strong>food</strong> security of the population, and (c) it is particularly <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g to study the role of <strong>women</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>Rwanda</strong> s<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>women</strong> were substantially more numerous than men right after the genocide.<br />

There are many female-headed households due to genocide and the government of <strong>Rwanda</strong><br />

gives <strong>women</strong> a central role <strong>in</strong> post-genocide reconstruction and poverty alleviation. Therefore,<br />

study<strong>in</strong>g <strong>women</strong>'s <strong>food</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>security</strong> at the <strong>in</strong>dividual level will contribute to a more general<br />

understand<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>women</strong>'s <strong>food</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>security</strong> and strategies aga<strong>in</strong>st it <strong>in</strong> a post-genocide/postconflict<br />

society. The study will f<strong>in</strong>d out if the <strong>women</strong> recognize that they are <strong>food</strong> <strong>in</strong>secure<br />

and then it can be easy to conv<strong>in</strong>ce them to participate actively <strong>in</strong> the strategies <strong>in</strong> place<br />

aim<strong>in</strong>g to fight <strong>food</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>security</strong> among them. S<strong>in</strong>ce most research <strong>in</strong> <strong>Rwanda</strong> talk about<br />

“households” rather than “<strong>in</strong>dividuals” when report<strong>in</strong>g <strong>food</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>security</strong>, the present study<br />

needs to f<strong>in</strong>d out <strong>how</strong> <strong>women</strong> with<strong>in</strong> their households are affected differently from men as<br />

well as reveal <strong>how</strong> <strong>food</strong> is distributed with<strong>in</strong> households <strong>in</strong> <strong>rural</strong> areas of <strong>Rwanda</strong>.<br />

III.<br />

Aim and research questions<br />

The present study seeks to analyze the causes of <strong>food</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>security</strong> among <strong>women</strong> liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong><br />

different households <strong>in</strong> the <strong>rural</strong> areas of <strong>Rwanda</strong>, as well as <strong>how</strong> the <strong>women</strong> experience<br />

different strategies aim<strong>in</strong>g to fight <strong>food</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>security</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Rwanda</strong>. The ma<strong>in</strong> research questions of<br />

the study are:<br />

4

• What are the causes of <strong>food</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>security</strong> among <strong>women</strong> <strong>in</strong> the <strong>rural</strong> households <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>Rwanda</strong> even <strong>in</strong> the <strong>rural</strong> zones of high <strong>food</strong> production?<br />

• How do <strong>women</strong> <strong>in</strong> the <strong>rural</strong> households <strong>in</strong> <strong>Rwanda</strong> experience and are affected by<br />

different strategies aim<strong>in</strong>g to eradicate <strong>food</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>security</strong>?<br />

IV.<br />

Theoretical departure po<strong>in</strong>ts<br />

4.1. What is security?<br />

Food <strong><strong>in</strong>security</strong> is part of the broader field of security studies. The dictionary def<strong>in</strong>es security<br />

<strong>in</strong> the most general sense as freedom from threats, fear and dangers (Miller 2001, 16). Thus,<br />

people are secure under two conditions. First, when no one poses a threat to them; second, if<br />

such threats exist, they will be secure if they have the capability to defend themselves aga<strong>in</strong>st<br />

the sources of danger at reasonable costs (Baldw<strong>in</strong> 1997, 13). This k<strong>in</strong>d of security is referred<br />

to as traditional security and it is the security of the state. It has five major dimensions: the<br />

orig<strong>in</strong> of threats, the nature of threats, the response, who is responsible for provid<strong>in</strong>g security,<br />

and core values (Miller 2001, 16).<br />

The idea of security has been at the heart of European political thought s<strong>in</strong>ce the crises of the<br />

seventeenth century. It was pr<strong>in</strong>cipally military and it is an objective of states to be achieved<br />

by diplomatic or military policies. Security was an <strong>in</strong>novation, <strong>in</strong> much of Europe, of the<br />

epoch of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars (Rothschild 1995, 60). Scholars such as<br />

Rothschild (1995), Arends (2008) as well as Waever (2008) have s<strong>how</strong>n that the<br />

understand<strong>in</strong>gs of security have changed quite significantly throughout history (Stritzel 2011,<br />

347). The senses of the word ‘security’ have changed cont<strong>in</strong>ually over time and the pluralistic<br />

understand<strong>in</strong>g of security as an objective of <strong>in</strong>dividuals and groups as well as of states was<br />

characteristic of the period from the mid-seventeenth century to the French Revolution. This<br />

understand<strong>in</strong>g has been claimed <strong>in</strong> the 1990s by the proponents of security as an extended<br />

concept. Efforts <strong>in</strong> redef<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g security put an emphasis on giv<strong>in</strong>g high priority to such issues<br />

as human rights, economics, the environment, drug traffic, epidemics, crime, or social<br />

<strong>in</strong>justice, <strong>in</strong> addition to the traditional concern with security from external military threats.<br />

Such efforts are usually supported by a mixture of normative arguments about which values<br />

of which people or groups of people should be protected, and empirical arguments as to the<br />

nature and magnitude of threats to those people (Baldw<strong>in</strong> 1997, 1).<br />

5

Accord<strong>in</strong>g to Rothschild (1995, 55), the 1990s “extended” security takes four ma<strong>in</strong> forms. In<br />

the first, the concept of security is extended from the security of nations to the security of<br />

groups and <strong>in</strong>dividuals: it is extended downwards from nations to <strong>in</strong>dividuals. In the second, it<br />

is extended from the security of nations to the security of the <strong>in</strong>ternational system, or of a<br />

supranational physical environment: it is extended upwards, from the nation to the biosphere.<br />

The extension <strong>in</strong> both cases is <strong>in</strong> the sorts of entities whose security is to be ensured. In the<br />

third form, the concept of security is extended horizontally, or to the sorts of security that are<br />

<strong>in</strong> question. Different entities (such as <strong>in</strong>dividuals, nations, and “systems”) cannot be expected<br />

to be secure or <strong>in</strong>secure <strong>in</strong> the same way; the concept of security is extended therefore, from<br />

military to political, economic, social, environmental, or “human” security. In a fourth form,<br />

the political responsibility for ensur<strong>in</strong>g security (or for <strong>in</strong>vigilat<strong>in</strong>g all these “concepts of<br />

security”) is itself extended: it is diffused <strong>in</strong> all directions from national states <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g<br />

upwards to <strong>in</strong>ternational <strong>in</strong>stitutions, downwards to regional or local government, and<br />

sideways to nongovernmental organizations, to public op<strong>in</strong>ion and the press, and to the<br />

abstract forces of nature or of the market. In the different extensions of security, <strong>food</strong> security<br />

comes <strong>in</strong> the third form where different types of security are mentioned and it is part of the<br />

human security because the <strong>in</strong>dividual is at the centre and <strong>food</strong> is among the basic human<br />

needs.<br />

However, the expansion of security has been criticized by different scholars who th<strong>in</strong>k that if<br />

security is everyth<strong>in</strong>g it ceases to be a useful concept and that expand<strong>in</strong>g the 'security studies'<br />

field will destroy its <strong>in</strong>tellectual coherence" Miller (2001, 26). As Deudney argues, if we<br />

beg<strong>in</strong> to speak about all the forces and events that threaten life, property and well-be<strong>in</strong>g (on a<br />

large scale) as threats to our national security, we shall soon dra<strong>in</strong> the term of any mean<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

All large-scale evils will become threats to national security and there will be a de-def<strong>in</strong>ition<br />

rather than a re-def<strong>in</strong>ition of security (Deudney cited by Miller 2001, 26).<br />

In the discussion of the extension of security, Miller (2001, 28) suggests that some aspects<br />

should be looked at as security concerns only if they have someth<strong>in</strong>g to do with war and<br />

peace. For example, environmental factors should be <strong>in</strong>cluded only if they affect the<br />

likelihood of violence (like water or energy shortages or other environmental scarcities) but<br />

not if they are ecological developments that threaten all of humanity without affect<strong>in</strong>g (for<br />

better or worse) the question of war and peace. However, limit<strong>in</strong>g security concerns to war<br />

and peace would exclude a variety of threats to human be<strong>in</strong>gs. Those who support to look at<br />

security as an extended concept suggest that the referent of security should be the <strong>in</strong>dividual,<br />

6

and the threats should not be limited to military ones. This is where different basic needs<br />

<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g <strong>food</strong> and human rights came to be security concerns because the <strong>in</strong>dividual is given<br />

high consideration <strong>in</strong> the extended security.<br />

4.2. Human Security<br />

‘State security is essential but does not necessarily ensure the safety of <strong>in</strong>dividuals and<br />

communities (Hoogensen and Rottem 2004, 158). It is <strong>in</strong> that perspective that, <strong>in</strong> the<br />

aftermath of the Cold War, there have been many calls for adopt<strong>in</strong>g a new conception of<br />

security and for extend<strong>in</strong>g the traditional concept. Thus, the United Nations Development<br />

Program advocated <strong>in</strong> 1994 a transition 'from nuclear security to human security', or to 'the<br />

basic concept of human security', def<strong>in</strong>ed as safety from 'such chronic threats as hunger,<br />

disease and repression', and 'protection from sudden and hurtful disruptions'. Furthermore, the<br />

International Commission on Global Governance recommended <strong>in</strong> 1995 that 'Global security<br />

must be broadened from its traditional focus on the security of states to the security of people<br />

and the planet' (Miller 2001, 2). Human security br<strong>in</strong>gs the focus of security to the level of<br />

the <strong>in</strong>dividual, thereby recogniz<strong>in</strong>g the constra<strong>in</strong>ts of a solely state oriented security<br />

perspective and acknowledg<strong>in</strong>g the importance of security at non-state levels. Thus, the<br />

<strong>in</strong>dividual or personal perspective becomes important (Hoogensen and Stuvøy 2006, 210).<br />

While its application varies widely, human security is by def<strong>in</strong>ition concerned with<br />

<strong>in</strong>dividuals and their rights rather than national militaries, and <strong>in</strong> particular the consequences<br />

of national or global events for <strong>in</strong>dividual human be<strong>in</strong>gs (Lemansky 2012, 62). The UN<br />

Secretary-General Kofi Annan states that human security can no longer be understood <strong>in</strong><br />

purely military terms. Rather, it must encompass economic development, social justice,<br />

environmental protection, democratization, disarmament, and respect for human rights and the<br />

rule of law.” Therefore, human security issues encompassed considerations for protection not<br />

only on national and <strong>in</strong>ternational levels, but also on regional, local, and <strong>in</strong>dividual levels<br />

(Annan 2001; den Boer and de Wilde 2008; McRae and Huberts 2001 ; Tadjbakhsh and<br />

Chenoy 2007 ; UNDP 1994 ).<br />

The Human Security shifted attention away from the military defence of national borders<br />

from external threats, towards a focus on the safety and security of <strong>in</strong>dividuals, who were<br />

often more at risk from their own governments than from external threats (Miller 2001, 19).<br />

To numerous human be<strong>in</strong>gs, the major security threat is posed by the states themselves, which<br />

violate their human rights, discrim<strong>in</strong>ate on ethnic, racial or gender basis, jail dissidents and<br />

even carry out ethnic cleans<strong>in</strong>g and mass kill<strong>in</strong>gs. However, although Human security has<br />

7

een criticized for mean<strong>in</strong>g everyth<strong>in</strong>g and therefore mean<strong>in</strong>g noth<strong>in</strong>g (Paris 2001), it has<br />

proven to be remarkably malleable. Its elasticity and non-specificity have allowed<br />

policymakers to fit a range of programmes with<strong>in</strong> its framework (Christie 2010, 176). Human<br />

security provides an effective framework that tells policymakers both where to look (at people<br />

<strong>in</strong>side of the state) to understand sources of conflict and what to look for <strong>in</strong> broad terms<br />

(th<strong>in</strong>gs that threaten, risk or impoverish people). What the policymakers <strong>in</strong> turn take from this<br />

is that these th<strong>in</strong>gs – previously seen as more general ‘development’ or ‘quality of life’ issues<br />

– are matters of security (Callaway & Harrelson- Stephens 2006; Clarke 2008). Those issues<br />

<strong>in</strong>clude basic material needs such as shelter and <strong>food</strong> that become threats to <strong>in</strong>dividuals’<br />

everyday life when they are not assured (Thomas 2000, 6). This is <strong>how</strong> <strong>food</strong> as a basic human<br />

need and human right became a security concern and it is a human right to be free from<br />

hunger.<br />

4.3. Gender and security<br />

Women’s security needs differ significantly from those of men (Bould<strong>in</strong>g 2000, 107; SAP<br />

Canada 2002, 3; United Nations 2002, 4–5). Women’s experiences have played a central role<br />

<strong>in</strong> gender analyses because <strong>women</strong> have been marg<strong>in</strong>alized, disadvantaged and made <strong>in</strong>secure<br />

with<strong>in</strong> exist<strong>in</strong>g gendered power structures. Some scholars, such as David Roberts (2008a, b),<br />

have used the language of human security to draw attention to the ways <strong>in</strong> which <strong>women</strong> and<br />

children suffer from forms of <strong>in</strong>securities that are obscured by traditional render<strong>in</strong>gs of<br />

security. Such studies take the human as referent and further ref<strong>in</strong>e it by tak<strong>in</strong>g ‘<strong>women</strong> and<br />

children’ as a particular focus because they are more disadvantaged, marg<strong>in</strong>alized and more<br />

<strong>in</strong>secure <strong>in</strong> times of <strong><strong>in</strong>security</strong>.<br />

Besides <strong>women</strong>’s vulnerability, one can’t ignore the multiple efforts <strong>in</strong> place regard<strong>in</strong>g<br />

help<strong>in</strong>g <strong>women</strong> to play a role <strong>in</strong> overcom<strong>in</strong>g their <strong>in</strong>securities. For example, the UN Security<br />

Council Resolution 1325 of October 2000 not only focuses on violence experienced by<br />

<strong>women</strong>, but also recognizes the important role a gender perspective has with regard to<br />

peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g and conflict resolution. The UN Security Council Resolution 1325 also<br />

encourages the participation of <strong>women</strong> at all levels of decision-mak<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g the military,<br />

on all aspects of prevention, conflict settlement, and peace build<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

As <strong>women</strong> play a big role <strong>in</strong> peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g and conflict resolution, they can also contribute <strong>in</strong><br />

fight<strong>in</strong>g <strong><strong>in</strong>security</strong>. Women are often the farmers who cultivate <strong>food</strong> crops and produce<br />

commercial crops alongside the men <strong>in</strong> their households as a source of <strong>in</strong>come. When <strong>women</strong><br />

8

have an <strong>in</strong>come, substantial evidence <strong>in</strong>dicates that the <strong>in</strong>come is more likely to be spent on<br />

<strong>food</strong> and children’s needs. Women are generally responsible for <strong>food</strong> selection and<br />

preparation and for the care and feed<strong>in</strong>g of children. Women are key to <strong>food</strong> security for their<br />

households and <strong>in</strong> many societies <strong>women</strong> supply most of the labor needed to produce <strong>food</strong><br />

crops and often control the use or sale of <strong>food</strong> produce grown on plots they manage.<br />

However, the asymmetries <strong>in</strong> ownership of, access to and control of livelihood assets (such as<br />

land, water, energy, credit, knowledge, and labor) negatively affect <strong>women</strong>’s <strong>food</strong> production<br />

(FAO 2006, 12; Quisumb<strong>in</strong>g et al. 1995).<br />

For example, <strong>women</strong> are less likely to own land and usually enjoy only use rights, mediated<br />

through a man relative. Studies cited <strong>in</strong> Deere and Doss (2006) <strong>in</strong>dicate that <strong>women</strong> held land<br />

<strong>in</strong> only 10 percent of Ghanaian households while men held land <strong>in</strong> 16–23 percent <strong>in</strong> Ghana;<br />

<strong>women</strong> are 5 percent of registered landholders <strong>in</strong> Kenya, 22.4 percent <strong>in</strong> the Mexican ejidos<br />

(communal farm<strong>in</strong>g lands), and 15.5 percent <strong>in</strong> Nicaragua. On average, men’s land hold<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

were almost three times the <strong>women</strong>’s land hold<strong>in</strong>gs. This compromised land access leads<br />

<strong>women</strong> to make suboptimal decisions with regard to crop choices and to obta<strong>in</strong> lower yields<br />

than would otherwise be possible if household resources were allocated efficiently (World<br />

Bank 2007).<br />

4.4. Food Security<br />

Food security can be traced back to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights <strong>in</strong> 1948 when<br />

the Universal Declaration of Human Rights stat<strong>in</strong>g that “Everyone has the right to a standard<br />

of liv<strong>in</strong>g adequate for the health and well-be<strong>in</strong>g of himself and his family, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g <strong>food</strong>…”<br />

(Marambanyika 2011). Article 11 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and<br />

Cultural Rights went further, <strong>in</strong> 1966, when it affirmed the “right of everyone to be free from<br />

hunger”. The right to <strong>food</strong> is even characterised as a “fundamental right” and is acknowledged<br />

as the primary economic right of a human be<strong>in</strong>g (Marambanyika 2011). This global concern<br />

heightened after the world <strong>food</strong> crisis of 1972–1974. In response to this <strong>food</strong> crisis, world<br />

leaders gathered <strong>in</strong> the 1974 World Food Conference and issued a declaration that “every man<br />

woman and child has an <strong>in</strong>alienable right to be free from hunger and malnutrition <strong>in</strong> order to<br />

develop fully and ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> their physical and mental faculties” (UN 1975, 2) The aim of the<br />

<strong>in</strong>ternational community was to <strong>in</strong>crease domestic agricultural production and to create<br />

<strong>in</strong>ternational gra<strong>in</strong> reserves, and this was one of the strategies to reduce hunger and ensure<br />

<strong>food</strong> security. In the beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g, the focus was on national and <strong>in</strong>ternational <strong>food</strong> supplies, but<br />

9

later shifted to access to <strong>food</strong> at household and <strong>in</strong>dividual levels after 1980 (Maxwell and<br />

Smith 1992). The 1980s shift of emphasis from '<strong>food</strong> production' via '<strong>food</strong> security' to<br />

'household <strong>food</strong> security' brought the household <strong>in</strong>to the picture as a target and unit of<br />

analysis (Gillepsie and Mason 1991, 32). The shift took place due to the realisation that the<br />

problem of hunger has more to do with <strong>in</strong>equalities <strong>in</strong> distribution and that <strong>in</strong>creased <strong>food</strong><br />

production was only part of the solution. S<strong>in</strong>ce then, the concept of <strong>food</strong> security has shifted<br />

from simply be<strong>in</strong>g a question of availability of <strong>food</strong> (at the national or even local level) to the<br />

more complex issue of access at the household or <strong>in</strong>dividual level (Maxwell and Smith 1992).<br />

Although <strong>food</strong> security refers to the availability of <strong>food</strong> and people’s ability to access it, <strong>food</strong><br />

security can be a confus<strong>in</strong>g concept because it is a complex, multifaceted problem <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g<br />

different <strong>in</strong>terl<strong>in</strong>ked aspects (McDonald 2010; DEFRA 2006). The def<strong>in</strong>ition of <strong>food</strong> security<br />

changed with time. For example, the 1974 World Food Summit def<strong>in</strong>ition focused largely on<br />

<strong>food</strong> supply, def<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>food</strong> security as the “availability at all times of adequate world <strong>food</strong><br />

supplies of basic <strong>food</strong>stuffs to susta<strong>in</strong> a steady expansion of <strong>food</strong> consumption and to offset<br />

fluctuations <strong>in</strong> production and prices” (UN 1975, 6). In the early 1980, the def<strong>in</strong>ition of <strong>food</strong><br />

security used by FAO (1983) was expanded to <strong>in</strong>clude both the physical and economic access<br />

as vital components of <strong>food</strong> security, a concern <strong>in</strong>corporated <strong>in</strong>to later def<strong>in</strong>itions as well,<br />

such as the 1996 Rome Declaration on World Food Security (Rome Declaration 1996). In<br />

2001, FAO further redef<strong>in</strong>ed this idea, add<strong>in</strong>g “social access” (ask<strong>in</strong>g whether all household<br />

members have equal access to <strong>food</strong>) <strong>in</strong>to <strong>food</strong> security, establish<strong>in</strong>g the def<strong>in</strong>ition used today:<br />

“Food security exists when all people, at all times, have physical, social and economic access<br />

to sufficient, safe and nutritious <strong>food</strong> that meets their dietary needs and <strong>food</strong> preferences for<br />

an active and healthy life” (FAO 2009). What all the def<strong>in</strong>itions have <strong>in</strong> common is not only<br />

the availability of <strong>food</strong> supplies, but also the ability of all people to ga<strong>in</strong> access to sufficient<br />

amounts of nutritious <strong>food</strong> for an active and healthy life (Sen 1982; Clay 2002; FAO 2003b;<br />

Runge et al. 2003; Barrett and Maxwell 2005; Shaw2007; Barret 2010 cited <strong>in</strong> McDonald<br />

2010).<br />

4.5. The dimensions of <strong>food</strong> security<br />

1. Availability of <strong>food</strong>: availability of sufficient <strong>food</strong> refers to the overall ability of the<br />

agricultural system to meet <strong>food</strong> demand (Schmidhuber and Tubiello (2007) and it is achieved<br />

if adequate <strong>food</strong> is ready to have at people’s disposal (Gross 2000, 5). Therefore, <strong>food</strong><br />

10

availability addresses the “supply side” of <strong>food</strong> security and is determ<strong>in</strong>ed by the level of <strong>food</strong><br />

production, stock levels and net trade.<br />

The paradox regard<strong>in</strong>g <strong>food</strong> availability and <strong>food</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>security</strong> is that national self-sufficiency is<br />

neither necessary nor sufficient to guarantee <strong>food</strong> security at the <strong>in</strong>dividual level<br />

(Schmidhuber and Tubiello 2007). As examples, Hong Kong and S<strong>in</strong>gapore are not selfsufficient<br />

(agriculture is nonexistent) but their populations are <strong>food</strong>-secure, whereas India is<br />

self-sufficient but a large part of its population is not <strong>food</strong>-secure.<br />

2. Access to <strong>food</strong>: As discussed above, an adequate supply of <strong>food</strong> at the national or<br />

<strong>in</strong>ternational level does not <strong>in</strong> itself guarantee household level <strong>food</strong> security. Food availability<br />

for the nation as a whole or even for the world as a whole does not necessarily translate <strong>food</strong><br />

availability to all sections of a given community or of each <strong>in</strong>dividual household (Sen 1981,<br />

43). Access refers to the household’s or <strong>in</strong>dividual’s command over <strong>food</strong> (Sen 1981), and it is<br />

ensured when all households have sufficient resources to obta<strong>in</strong> appropriate <strong>food</strong>s (through<br />

production, purchase or donation) for a nutritious diet (Gross 2000).<br />

(Maxwell and Smith 1992, 11) discuss access to <strong>food</strong> us<strong>in</strong>g the term ‘entitlement’ and they<br />

say that the entitlement of a person stands for the different alternative commodity bundles that<br />

a person can acquire through the uses of various legal channels of acquirement open to<br />

someone <strong>in</strong> his position. The entitlement relations of <strong>in</strong>dividuals are determ<strong>in</strong>ed by what they<br />

own, what they produce, what they can trade, and what they <strong>in</strong>herit or are given<br />

3. Food utilization: utilization is only discussed from a biological perspective and it<br />

encompasses all <strong>food</strong> safety and quality aspects of nutrition; its subdimensions are therefore<br />

related to health, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g the sanitary conditions across the entire <strong>food</strong> cha<strong>in</strong> (Gross 2000;<br />

Schmidhuber and Tubiello 2007). It is not enough that someone is gett<strong>in</strong>g what appears to be<br />

an adequate quantity of <strong>food</strong> if that person is unable to make use of the <strong>food</strong>. This is where<br />

<strong>food</strong> security and nutrition get connected. People are <strong>food</strong> secure if the <strong>food</strong> <strong>in</strong>take at their<br />

disposal is beneficial to their bodies and if their bodies use the <strong>food</strong> <strong>in</strong>take <strong>in</strong> a healthy and<br />

nutritious way. Utilization also refers to the proper use of <strong>food</strong> and <strong>in</strong>cludes the existence of<br />

appropriate <strong>food</strong> process<strong>in</strong>g and storage practices, adequate knowledge and application of<br />

nutrition and childcare and adequate health and sanitation services (FAO 2000; FANTA<br />

2006). This dimension is not relevant for the present study due to its biological character and<br />

it won’t be developed further.<br />

11

For <strong>food</strong> security to be assured, availability, access, and utilization need to be stable over<br />

time. Even if people’s <strong>food</strong> <strong>in</strong>take is adequate today, they are still considered to be <strong>food</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>secure if they have <strong>in</strong>adequate access to <strong>food</strong> on a periodic basis, risk<strong>in</strong>g a deterioration of<br />

their nutritional status. The role of governments is to plan and set adequate strategies that<br />

enable their populations to be <strong>food</strong> secure all the time. Stability refers to the temporal<br />

determ<strong>in</strong>ant of Food and Nutrition Security (FNS) and affects availability, access, and<br />

utilization (Gross 2000). Stability makes it possible to dist<strong>in</strong>guish between chronic and<br />

transitory <strong>food</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>security</strong>. Chronic <strong>food</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>security</strong> means that a household runs a cont<strong>in</strong>ually<br />

high risk of <strong>in</strong>ability to meet the <strong>food</strong> needs of household members (Maxwell and Smith<br />

1992, 15). In contrast, transitory <strong>food</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>security</strong> occurs when a household faces a temporary<br />

decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> the security of its entitlements and the risk of failure to meet <strong>food</strong> needs is of short<br />

duration. This category can be further divided <strong>in</strong>to cyclical and temporary <strong>food</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>security</strong>.<br />

Temporary <strong>food</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>security</strong> occurs for a limited time because of unforeseen and unpredictable<br />

circumstances while cyclical or seasonal <strong>food</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>security</strong> occurs when there is a regular pattern<br />

<strong>in</strong> the periodicity of <strong>in</strong>adequate access to <strong>food</strong> (CIDA 1989, 21). For <strong>food</strong> security objectives<br />

to be realized, all the dimensions must be fulfilled simultaneously <strong>in</strong> order to make sure that<br />

all people, at all times have access to the <strong>food</strong> that enables them to live an active and healthy<br />

life.<br />

4.6. Social aspects of <strong>food</strong> security<br />

The highest state of <strong>food</strong> security requires not just secure and stable access to a sufficient<br />

quantity of <strong>food</strong>, but also access to <strong>food</strong> that is nutritionally of adequate quality, culturally<br />

acceptable, procured without any loss of dignity and self-determ<strong>in</strong>ation, and consistent with<br />

the realization of other basic needs. Therefore, <strong>food</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>security</strong> is not an objectively def<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

level of access to <strong>food</strong> or quality, but rather the level or quality that people perceive to be<br />

<strong>in</strong>adequate (Maxwell and Smith 1992, 41). For example <strong>in</strong> India, subjective questions have<br />

been <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> the national survey to ask whether respondents consider their <strong>food</strong> <strong>in</strong>take<br />

adequate. Results s<strong>how</strong>ed that 18.5 percent households, on average <strong>in</strong> India, self−reported<br />

chronic and/or seasonal <strong>food</strong> <strong>in</strong>adequacy. This compared with figures of 14.6 percent<br />

accord<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>food</strong> behavioral thresholds and 50.2 percent accord<strong>in</strong>g to caloric norms (M<strong>in</strong>has<br />

1990, reported <strong>in</strong> Gillepsie and Mason 1991, 31). It is important to f<strong>in</strong>d out if the population<br />

recognizes that they are <strong>food</strong> <strong>in</strong>secure and then it can be easy to conv<strong>in</strong>ce them to take part of<br />

the strategies <strong>in</strong> place aim<strong>in</strong>g to fight <strong>food</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>security</strong> among them. In addition, Mudimu<br />

12

(2008) says that <strong>food</strong> security <strong>in</strong> Zimbabwe is ma<strong>in</strong>ly def<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> the context of availability or<br />

access to cereals, particularly maize as a staple <strong>food</strong> crop. This is because cereals such as<br />

maize, sorghum, pearl millet, f<strong>in</strong>ger millet and wheat make up the traditional <strong>food</strong> gra<strong>in</strong> crops<br />

at the expense of horticultural products which are essentially for direct consumption. Food<br />

security also touches areas such as consistency with local <strong>food</strong> habits and cultural<br />

acceptability (Oomen 1988; Oshaug 1986; Eide et al 1985, 1986; Teller et al 1991 cited <strong>in</strong><br />

Maxwell and Smith 1992, 39). In particular, Oshaug (1986, 5-9, 10) says that efforts to direct<br />

changes <strong>in</strong> <strong>food</strong> patterns for optimal nutritional conditions should always take the <strong>in</strong>digenous<br />

<strong>food</strong> culture and <strong>food</strong> production pattern of a society as a start<strong>in</strong>g po<strong>in</strong>t. Therefore, a country<br />

and people are <strong>food</strong> secure when their <strong>food</strong> system operates <strong>in</strong> a way that removes the fear<br />

that there will not be enough to eat. In particular, <strong>food</strong> security will be achieved when the<br />

poor and vulnerable, particularly <strong>women</strong> and children and those liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> marg<strong>in</strong>al areas, have<br />

secure access to the <strong>food</strong> they want.<br />

4.7. The role of the <strong>in</strong>ternational community <strong>in</strong> <strong>food</strong> security<br />

Ensur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>food</strong> security has been a prom<strong>in</strong>ent feature of global agreements s<strong>in</strong>ce World War II<br />

and some of them set ambitious targets to address <strong>food</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>security</strong>. For example, the World<br />

Food Summit of 1996 sought to halve the number of the undernourished by 2015, while the<br />

millennium development goals (MDGs) set <strong>in</strong> 2000, aspired to reduce by half the proportion<br />

of people suffer<strong>in</strong>g from hunger (Mc Donald 2010, 4).<br />

Dur<strong>in</strong>g the previous decades, many countries were satisfied <strong>in</strong> terms of <strong>food</strong> security because<br />

they were rely<strong>in</strong>g on cheaper imports that they thought would be always or usually available<br />

(Behnassi and Yaya 2011, 106). In this context, local <strong>food</strong> production was not often necessary<br />

and many develop<strong>in</strong>g countries have consequently reduced it by reference to <strong>in</strong>ternational<br />

donors’ <strong>in</strong>structions. Some of the structural adjustment policies <strong>in</strong>clude (a) dismantl<strong>in</strong>g<br />

market<strong>in</strong>g boards and guaranteed prices for farmers’ products; (b) phas<strong>in</strong>g out or elim<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g<br />

subsidies and support such as fertilizer, mach<strong>in</strong>es and agricultural <strong>in</strong>frastructure; and (c)<br />

reduc<strong>in</strong>g tariffs of <strong>food</strong> products to low levels (Behnassi and Yaya 2011, 107).<br />

However, the high price of many <strong>food</strong> items <strong>in</strong> recent years makes <strong>food</strong> imports <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly<br />

expensive, and <strong>in</strong>tensifies <strong>in</strong>flation of <strong>food</strong> prices <strong>in</strong> local markets. There have also been cases<br />

of shortages, as some countries plac<strong>in</strong>g orders – for example for rice – have found that the<br />

supply is not guaranteed sometimes because of export restrictions by the exporters of the <strong>food</strong><br />

items.<br />

13

Agriculture has important functions to perform <strong>in</strong> the economic development of most<br />

develop<strong>in</strong>g countries (Haruna and Umar 2011). However, many agricultural economists<br />

believed agricultural <strong>in</strong>crease can only be achieved with <strong>in</strong>troduction of new technology <strong>in</strong><br />

traditional agriculture (Mohammed et al. 2005). The <strong>in</strong>troduction of simple technologies <strong>in</strong><br />

the form of improved seeds, agrochemicals, fertilizers and improved cultural practices is one<br />

of the quickest ways of improv<strong>in</strong>g agricultural production technology rais<strong>in</strong>g the productivity<br />

of agricultural resources (Haruna and Kushwaha 2003). Although a lot of efforts have been<br />

made to improve agricultural systems <strong>in</strong> order to <strong>in</strong>crease the agricultural production both<br />

globally and <strong>in</strong>ternationally, it is still necessary to <strong>in</strong>vestigate <strong>in</strong> <strong>how</strong> the vulnerable poor<br />

members of communities benefit from the <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> agricultural production.<br />

4.8. The role of governments <strong>in</strong> <strong>food</strong> security<br />

Governments <strong>in</strong> the develop<strong>in</strong>g countries found it necessary to <strong>in</strong>vest <strong>in</strong> efforts enabl<strong>in</strong>g them<br />

to <strong>in</strong>crease their own agricultural production. This is because, although the factors beh<strong>in</strong>d the<br />

<strong>food</strong> crisis are numerous, one of the longer-term reasons rema<strong>in</strong>s the decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> agricultural<br />

production <strong>in</strong> many develop<strong>in</strong>g countries (Behnassi and Yaya 2011, 107). <strong>Rwanda</strong>’s longterm<br />

development strategy articulated <strong>in</strong> the document “Vision 2020” has the ultimate goal of<br />

vanquish<strong>in</strong>g poverty and misery, and atta<strong>in</strong>s a per capita <strong>in</strong>come of middle-<strong>in</strong>come countries<br />

by the year 2020. Agricultural transformation is one of the major pillars for achievement of<br />

the Vision 2020 goals. In order to achieve <strong>food</strong> security, the government of <strong>Rwanda</strong> uses<br />

policies such as the Economic Development and Poverty Reduction Strategy (EDPRS), the<br />

National Agricultural Policy (NAP), and the Strategic Plan for the Transformation of<br />

Agriculture (PSTA). 2 The agricultural sector rema<strong>in</strong>s the economic backbone of <strong>Rwanda</strong>; it<br />

employs about 87 percent of the work<strong>in</strong>g population, produces around 46 percent of GDP and<br />

2 EDPRS identifies seven priority areas, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g two that are relevant to <strong>food</strong> and nutrition security: “Poverty<br />

and vulnerability reduction” and “<strong>rural</strong> development and agricultural transformation”. The EDPRS was<br />

developed <strong>in</strong> 2007 as a medium term strategy and the United Nations Development Assistance Framework<br />

(UNDAF) 2008-2012 is entirely aligned with the EDPRS. In addition, the National Agricultural Policy (NAP)<br />

was adopted <strong>in</strong> 2004 and is based on the guidel<strong>in</strong>es of Vision 2020. Its overall objective is to ensure susta<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

economic growth through poverty reduction and <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g farmers' <strong>in</strong>comes. Its specific objectives are: i)<br />

empower <strong>rural</strong> communities as active actors <strong>in</strong> the development of agriculture, ii) <strong>in</strong>crease agricultural<br />

production, livestock and forestry through improved productivity of land and water iii) <strong>in</strong>crease cash <strong>in</strong>come<br />

through diversification of economic activities <strong>in</strong> <strong>rural</strong> areas iv) strengthen the l<strong>in</strong>k production/market v)<br />

susta<strong>in</strong>able management of natural resources and vi) improv<strong>in</strong>g the economic and social status of <strong>women</strong> and<br />

youth farmers <strong>in</strong> <strong>rural</strong> areas.<br />

14

generates about 80 percent of the total export revenues. The ultimate objective of the<br />

agricultural policy is to contribute to the national economic growth, to achieve improved <strong>food</strong><br />

security and the nutritional status of the population and <strong>in</strong>crease the <strong>in</strong>comes of the <strong>rural</strong><br />

households (Republic of <strong>Rwanda</strong> 2004, 1). Agricultural <strong>in</strong>crease is very beneficial especially<br />

for <strong>rural</strong> households s<strong>in</strong>ce over 80 percent of <strong>Rwanda</strong>'s population live <strong>in</strong> <strong>rural</strong> areas and a<br />

large part of the farmers have an average size of their land less than 1 hectare per household.<br />

The <strong>rural</strong> <strong>in</strong>comes come ma<strong>in</strong>ly from the sale of <strong>food</strong> crops, livestock and crops. However,<br />

there may be a tension between the aim of <strong>in</strong>creased agricultural production and <strong>in</strong>creased<br />

<strong>food</strong> security, for <strong>in</strong>stance when policies oblige people to grow export crops rather than mixed<br />

crops <strong>in</strong> their lands. In <strong>Rwanda</strong>, the agricultural production rema<strong>in</strong>s <strong>in</strong>sufficient to meet the<br />

needs of the grow<strong>in</strong>g population thus <strong>in</strong>duc<strong>in</strong>g <strong>food</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>security</strong> and <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g poverty levels<br />

especially <strong>in</strong> <strong>rural</strong> areas where it is hard to f<strong>in</strong>d non-agricultural work. Although agricultural<br />

productivity is not the only solution to <strong>food</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>security</strong>, it is essential because higher<br />

productivity, especially <strong>in</strong> <strong>food</strong> staples and on smallholder farms, builds <strong>food</strong> security by<br />

<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g <strong>food</strong> availability and lower<strong>in</strong>g the price of staple <strong>food</strong>s, thus improv<strong>in</strong>g access. It<br />

also boosts the <strong>in</strong>comes of millions of smallholder farmers, rais<strong>in</strong>g liv<strong>in</strong>g standards and thus<br />

enlarg<strong>in</strong>g people’s capabilities and knowledge (United Nations Development Programme<br />

2012, 22).<br />

V. Methodology<br />

5.1. Design of the study<br />

The present study is qualitative. Qualitative research is a means for explor<strong>in</strong>g and<br />

understand<strong>in</strong>g the mean<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>dividuals or groups ascribe to a social or human problem<br />

(Cresswell 2009, 3). The advantage of qualitative research is us<strong>in</strong>g multiple forms of data<br />

collection rather than rely on a s<strong>in</strong>gle data source (Cresswell 2009, 175). The present study<br />

will use semi-structured <strong>in</strong>terviews and observation.<br />

5.2. Research <strong>in</strong>struments/ <strong>in</strong>terviews and observation<br />

The present study will collect data us<strong>in</strong>g semi-structured <strong>in</strong>terviews and observation. While<br />

conduct<strong>in</strong>g semi-structured <strong>in</strong>terviews I will have an <strong>in</strong>terview guide i.e. a list of questions or<br />

specific topics to be covered. Due to flexibility <strong>in</strong> semi-structured <strong>in</strong>terviews, the order of<br />

questions will change where necessary and some questions that are not <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> the guide<br />

15

will be asked bas<strong>in</strong>g on what the <strong>in</strong>terviewees will say (Bryman 2008, 438). 3 By us<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

same <strong>in</strong>terview guide everywhere, I will be able to f<strong>in</strong>d out what similarities and differences<br />

exist among <strong>women</strong> from the two different types of households and from there conclusions<br />

will be drawn about <strong>food</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>security</strong> among <strong>women</strong> <strong>in</strong> the <strong>rural</strong> households of <strong>Rwanda</strong>n zones<br />

of high <strong>food</strong> production.<br />

The study will also <strong>in</strong>clude observation of <strong>women</strong> <strong>in</strong> the households that will be <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong><br />

the study to access some <strong>in</strong>formation that is not easily accessed <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>terviews. Observation<br />

enables the researcher to be <strong>in</strong> much closer contact with people for a longer period of time.<br />

Because of the unstructured nature of participant observation, it is more likely to uncover<br />

unexpected topics or issues (Bryman 2008, 465-466). It is <strong>in</strong> that perspective that visits to the<br />

<strong>women</strong>’s families will make it possible to access the <strong>in</strong>formation that can’t be accessed <strong>in</strong><br />

semi-structured <strong>in</strong>terviews with them. For example, there is a policy that requires every<br />

family <strong>in</strong> the <strong>rural</strong> areas of <strong>Rwanda</strong> to have a vegetable garden. By visit<strong>in</strong>g each selected<br />

household, I will be able to observe and f<strong>in</strong>d out whether they have a vegetable garden or not,<br />

which plants are more likely to be found <strong>in</strong> the gardens, and other issues related to the garden.<br />

More issues and realities will be revealed as I spend more time <strong>in</strong> natural sett<strong>in</strong>gs with them<br />

because I will observe them when they are work<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> their gardens and I will be able to hear<br />

them talk to one another as they work.<br />

5.3. Who will participate<br />

The present study will conduct <strong>in</strong>terviews with two ma<strong>in</strong> groups of people: the group of<br />

<strong>women</strong> who live <strong>in</strong> households headed by a married couple, and the group of <strong>women</strong> who live<br />

<strong>in</strong> female-headed households. The <strong>women</strong> will be selected us<strong>in</strong>g strategic sampl<strong>in</strong>g. 4 Us<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>women</strong> from both groups will enable me to get experiences from <strong>women</strong> with different<br />

experiences and contexts. There will be 20 <strong>women</strong> from households headed by a married<br />

couple and 20 <strong>women</strong> from households headed by a woman. The study will also <strong>in</strong>terview<br />

central and local government officials relevant for the study.<br />

5.4. Where<br />

3 In a semi-structured <strong>in</strong>terview the researcher has a list of questions or fairly specific topics to be covered, often<br />

referred to as an <strong>in</strong>terview guide but the <strong>in</strong>terviewee has a great deal of leeway <strong>in</strong> <strong>how</strong> to reply. The order of<br />

questions may change and questions that are not <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> the guide may be asked as the <strong>in</strong>terviewer picks up<br />

on th<strong>in</strong>gs said by <strong>in</strong>terviewees (Bryman 2008, 438)<br />

4 The goal of strategic sampl<strong>in</strong>g is to sample cases/participants <strong>in</strong> a strategic way, so that those sampled are<br />

relevant to the research questions that are be<strong>in</strong>g posed (Bryman 2008, 415).<br />

16

References<br />

Ansoms and McKay (2010). A quantitative analysis of poverty and livelihood profiles:<br />

The case of <strong>rural</strong> <strong>Rwanda</strong>. Elsevier Ltd accessed at<br />

http://www.journals.elsevier.com/<strong>food</strong>-policy/#description<br />

Baldw<strong>in</strong>, D.A. (1997). The Concept of Security. Review of International Studies (1997),<br />

23, 5-26. British International Studies Association<br />

Behnassi, M. et al. (eds.) (2011). Global Food Insecurity: Reth<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g Agricultural and<br />

Rural Development Paradigm and Policy, DOI 10.1007/978-94-007-0890-7_6,© Spr<strong>in</strong>ger<br />

Science+Bus<strong>in</strong>ess Media B.V. 2011<br />

Cornwall, A. and I. Scoones (1993). “Explor<strong>in</strong>g Diversity and Difference <strong>in</strong> Food Systems<br />

Under Stress” . In J. Pottier (ed.) African Food Systems Under Stress. Issues, Perspectives<br />

and Methodologies. Desktop Display, Brighton, pp.67-95<br />

DEFRA (Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs) (2006). Food Security<br />

and the UK: An Evidence and Analysis Paper.<br />

https://statistics.defra.gov.uk/esg/reports/<strong>food</strong> security/ (January 30, 2012)<br />

Ellis, F. (1998). “Household strategies and <strong>rural</strong> livelihood diversification,” Journal of<br />

Development Studies 35(1): 1-38.<br />

FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations)(2009). The State of Food<br />

Insecurity <strong>in</strong> the World 2009: Economic crises- Impacts and Lessons Learned. Rome:<br />

FAO.<br />

Gillespie, Stuart & Kadiyala, Suneetha (2005). "HIV/AIDs and <strong>food</strong> and nutrition<br />

security," Food policy reviews 7, International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).<br />

Haruna, U. and Umar, M.B (2011). Agricultural Development for Food security and<br />

susta<strong>in</strong>ability <strong>in</strong> Nigeria <strong>in</strong> Behnassi, M. et al. (eds.), Global Food Insecurity: Reth<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Agricultural and Rural Development Paradigm and Policy, DOI 10.1007/978-94-007-<br />

0890-7_6,© Spr<strong>in</strong>ger Science+Bus<strong>in</strong>ess Media B.V. 2011<br />

Hoogensen, G. and Stuvøy, K. (2006). Gender, Resistance and Human Security. Security<br />

Dialogue 2006 37: 207<br />

Lemanski, C. (2012). Everyday human (<strong>in</strong>)security: Rescal<strong>in</strong>g for the Southern city.<br />

Security Dialogue 2012 43:61 available onl<strong>in</strong>e at http://sdi.sagepub.com/content/43/1/61<br />

Liwenga, E.T (2003). Food <strong><strong>in</strong>security</strong> and Cop<strong>in</strong>g Strategies <strong>in</strong> Semiarid Areas.<br />

Stockholm. Stockholm University<br />

18

Maxwell, S. and M. Smith (1992). “Household Food Security: A Conceptual Review,” <strong>in</strong><br />

S. Maxwell and T. Frankenberger (eds) Household <strong>food</strong> Security: Concepts, Indicators,<br />

and Measurements: A Technical Review. New York and Rome. UNICEF and IFAD.<br />

McDonald, Bryan L. (2010). Food security. Cambridge. Polity Press.<br />

Philips, Anne (1998) Fem<strong>in</strong>ism and Politics. Oxford & New York: Oxford<br />

Press<br />

(UK).<br />

University<br />

Pottier, J. (ed.) (1993). African Food Systems Under Stress. Issues, Perspectives and<br />

Methodologies. Desktop Display, Brighton, pp.67-95<br />

Republic of <strong>Rwanda</strong> (2010). A proposal to distribute a cow to every poor family <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>Rwanda</strong>. Office of the Ombudsman<br />

Republic of <strong>Rwanda</strong> (2010). Operational Audit Report of <strong>Rwanda</strong> Agricultural<br />

Development Authority. Office of the Ombudsman<br />

Sen, A. (1981). Poverty and Fam<strong>in</strong>es : An Essay on Entitlements and Deprivation,<br />

Oxford, Clarendon Press.<br />

Schmidhuber and Tubiello (2007). Global Food security under Climate Change. The<br />

National Academy of Sciences of the USA 104: 19703-19708<br />

Tickner, J. Ann (1995). 'Re-vision<strong>in</strong>g Security', <strong>in</strong> Ken Booth and Steve Smith(eds.)<br />

International Relations Theory Today (Oxford: OUP 1995)<br />

Toulm<strong>in</strong> (1986). “Access to Food, Dry Season Strategies and Household Size Amongst<br />

the Bambara at Central mali” IDS Bullet<strong>in</strong> 17 (3), pp58-66<br />

Yuval-Davis, Nira (2000). Gender and Nation. London: Sage Publications<br />

19