using nutrition to ease the pain of osteoarthritis - HillsVet

using nutrition to ease the pain of osteoarthritis - HillsVet

using nutrition to ease the pain of osteoarthritis - HillsVet

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>nutrition</strong> myths and truths, facts and fallacies<br />

Using Nutrition <strong>to</strong> Ease <strong>the</strong> Pain <strong>of</strong> Osteoarthritis<br />

Ron McLaughlin, DVM, DVSc, DACVS, Department <strong>of</strong> Clinical Sciences, Mississippi State University, College <strong>of</strong> Veterinary Medicine<br />

Introduction<br />

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a progressive, degenerative dis<strong>ease</strong> <strong>of</strong> synovial joints characterized by <strong>pain</strong>, disability,<br />

destruction <strong>of</strong> articular cartilage, and bony remodeling. It is <strong>the</strong> most common cause <strong>of</strong> lameness in dogs and is<br />

estimated <strong>to</strong> affect 20% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> canine population over 1 year <strong>of</strong> age. The radiographic prevalence <strong>of</strong> CHD has<br />

been reported <strong>to</strong> be as high as 70% in golden retrievers and Rottweilers. Risk fac<strong>to</strong>rs for developing OA include<br />

age, breed, genetics, trauma, obesity and developmental orthopedic conditions.<br />

Primary OA is rare in dogs and is <strong>the</strong> result <strong>of</strong> defective articular cartilage structure and biosyn<strong>the</strong>sis. Secondary<br />

OA is very common and may be caused by joint trauma, inflamma<strong>to</strong>ry conditions, congenital and developmental<br />

abnormalities, and metabolic, endocrine, neuropathic, neoplastic, or iatrogenic causes. Once <strong>the</strong> dis<strong>ease</strong> process<br />

begins, a progressive cascade <strong>of</strong> mechanical and biochemical events occurs resulting in cartilage destruction,<br />

subchondral bony sclerosis, synovial membrane inflammation, en<strong>the</strong>siophy<strong>to</strong>sis, and <strong>the</strong> development <strong>of</strong><br />

periarticular osteophytes.<br />

Pathophysiology<br />

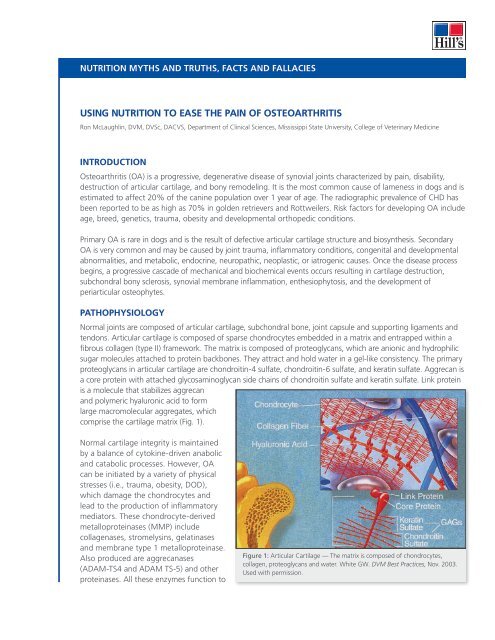

Normal joints are composed <strong>of</strong> articular cartilage, subchondral bone, joint capsule and supporting ligaments and<br />

tendons. Articular cartilage is composed <strong>of</strong> sparse chondrocytes embedded in a matrix and entrapped within a<br />

fibrous collagen (type II) framework. The matrix is composed <strong>of</strong> proteoglycans, which are anionic and hydrophilic<br />

sugar molecules attached <strong>to</strong> protein backbones. They attract and hold water in a gel-like consistency. The primary<br />

proteoglycans in articular cartilage are chondroitin-4 sulfate, chondroitin-6 sulfate, and keratin sulfate. Aggrecan is<br />

a core protein with attached glycosaminoglycan side chains <strong>of</strong> chondroitin sulfate and keratin sulfate. Link protein<br />

is a molecule that stabilizes aggrecan<br />

and polymeric hyaluronic acid <strong>to</strong> form<br />

large macromolecular aggregates, which<br />

comprise <strong>the</strong> cartilage matrix (Fig. 1).<br />

Normal cartilage integrity is maintained<br />

by a balance <strong>of</strong> cy<strong>to</strong>kine-driven anabolic<br />

and catabolic processes. However, OA<br />

can be initiated by a variety <strong>of</strong> physical<br />

stresses (i.e., trauma, obesity, DOD),<br />

which damage <strong>the</strong> chondrocytes and<br />

lead <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> production <strong>of</strong> inflamma<strong>to</strong>ry<br />

media<strong>to</strong>rs. These chondrocyte-derived<br />

metalloproteinases (MMP) include<br />

collagenases, stromelysins, gelatinases<br />

and membrane type 1 metalloproteinase.<br />

Also produced are aggrecanases<br />

(ADAM-TS4 and ADAM TS-5) and o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

proteinases. All <strong>the</strong>se enzymes function <strong>to</strong><br />

Figure 1: Articular Cartilage — The matrix is composed <strong>of</strong> chondrocytes,<br />

collagen, proteoglycans and water. White GW. DVM Best Practices, Nov. 2003.<br />

Used with permission.

<strong>nutrition</strong> myths and truths, facts and fallacies<br />

break down cartilage matrix faster than new matrix can be produced. The products <strong>of</strong> cartilage breakdown are<br />

antigenic and provoke synovitis.<br />

Synovial macrophages and leukocytes are abundant sources <strong>of</strong> cy<strong>to</strong>kines, procoagulant fac<strong>to</strong>rs, proteinases<br />

and oxygen-derived free radicals including nitric oxide (NO-). Interleukin-1-beta (IL-1) and tumor necrosis<br />

fac<strong>to</strong>r-alpha (TNF-) are <strong>the</strong> predominant proinflamma<strong>to</strong>ry cy<strong>to</strong>kines syn<strong>the</strong>sized during <strong>the</strong> OA process. IL-1<br />

stimulates <strong>the</strong> breakdown <strong>of</strong> matrix proteins and <strong>the</strong> accumulation <strong>of</strong> degradation products. TNF- appears <strong>to</strong><br />

drive <strong>the</strong> inflamma<strong>to</strong>ry process. Both substances induce articular cells <strong>to</strong> produce o<strong>the</strong>r cy<strong>to</strong>kines and incr<strong>ease</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong>ir own production, as well as stimulate production <strong>of</strong> prot<strong>ease</strong>s and prostaglandin E 2<br />

(PGE 2<br />

). Numerous<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r cy<strong>to</strong>kines and growth fac<strong>to</strong>rs are also involved in OA pathophysiology. These inflamma<strong>to</strong>ry cy<strong>to</strong>kines<br />

contribute <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> perpetuation and progression <strong>of</strong> arthritis by sustaining catabolic processes. Once initiated,<br />

<strong>the</strong>se molecular and cellular pathways form a self-perpetuating cycle.<br />

Clinical Presentation<br />

Signalment: A patient’s breed, age, gender and body weight provide valuable information when assessing <strong>the</strong><br />

patient’s relative risk for <strong>osteoarthritis</strong>. Rapidly growing large breed dogs, for example, are <strong>of</strong>ten affected with<br />

developmental orthopedic conditions that can lead <strong>to</strong> OA. Older dogs <strong>of</strong>ten demonstrate signs <strong>of</strong> OA. Obese<br />

animals appear more susceptible <strong>to</strong> OA and, because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir added weight, may be more debilitated by <strong>the</strong><br />

dis<strong>ease</strong>. One long term study has documented that <strong>the</strong> prevalence and severity <strong>of</strong> <strong>osteoarthritis</strong> is greater in dogs<br />

with body condition scores above normal. Over <strong>the</strong> life span <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se same dogs, <strong>the</strong> mean age at which 50% <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> dogs required long-term treatment for clinical signs attributable <strong>to</strong> <strong>osteoarthritis</strong> was significantly earlier (10.3<br />

years, p

<strong>nutrition</strong> myths and truths, facts and fallacies<br />

hip joint<br />

KNEE joint<br />

healthy hip joint<br />

arthritic hip joint healthy knee joint arthritic knee joint<br />

Figure 2: Radiographic images <strong>of</strong> healthy and arthritic hip and knee joints demonstrating typical changes<br />

thickening <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> joint capsule, sclerosis or erosion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> subchondral bone, periarticular osteophyte formation,<br />

en<strong>the</strong>siophytes, and joint mice (Fig. 2).<br />

Arthrocentesis and synovial fluid analysis: Synovial fluid collected from affected joints is examined for<br />

volume, color, clarity, viscosity, cy<strong>to</strong>logy, and biochemical analysis. Fluid from patients with OA may be clear or<br />

pale yellow and slightly turbid due <strong>to</strong> an incr<strong>ease</strong> in inflamma<strong>to</strong>ry cells. It typically contains synovial cells and<br />

less than 5 x 10 3 /L mononuclear cells (and a few red blood cells may also be present). Polymorphonuclear cells<br />

typically constitute 0-12% <strong>of</strong> cells. Synovial fluid analysis alone may not differentiate OA joints from normal<br />

joints (particularly in <strong>the</strong> early stages <strong>of</strong> OA), but is valuable in ruling out septic and immune-mediated arthritis.<br />

Physical<br />

Rehabilitation<br />

NSAID<br />

Adjunct<br />

Multimodal<br />

Osteoarthritis<br />

Management<br />

Weight Control<br />

and Exercise<br />

EPA-rich<br />

Diet<br />

Figure 3: Multimodal management <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>osteoarthritis</strong><br />

Chondroprotectant<br />

Treatment Of OA<br />

Multimodal medical treatment is recommended for OA, including<br />

weight reduction, proper <strong>nutrition</strong>, exercise control, physical<br />

<strong>the</strong>rapy, and <strong>the</strong> administration <strong>of</strong> anti-inflamma<strong>to</strong>ry medications,<br />

analgesics, and <strong>osteoarthritis</strong> dis<strong>ease</strong> modifying agents (Fig. 3).<br />

Exercise and Physical Rehabilitation: Exercise and physical <strong>the</strong>rapy<br />

are <strong>of</strong>ten used as part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> treatment for OA in humans and dogs.<br />

Exercise reduces obesity (a primary contribu<strong>to</strong>r <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> progression <strong>of</strong><br />

OA) and controlled exercise may help improve strength and range<br />

<strong>of</strong> motion in joints. Exercise may also reduce <strong>the</strong> need for analgesic<br />

medications. Low-impact exercises such as walking and swimming<br />

are preferred. The activity should be initiated gradually and incr<strong>ease</strong>d<br />

as joint function improves. Warm compresses, coldpacks, massage<br />

<strong>the</strong>rapy, electro<strong>the</strong>rapy, and ultrasound are techniques used in<br />

treatment <strong>of</strong> both human and canine OA patients.<br />

Nutrition: Fish oil as a source <strong>of</strong> omega-3 fatty acids has been shown <strong>to</strong> reduce inflammation and <strong>pain</strong> in<br />

mammals. Certain omega-3 fatty acids have been shown <strong>to</strong> reduce <strong>the</strong> expression and activity <strong>of</strong> proteoglycandegrading<br />

enzymes, <strong>the</strong>reby having <strong>the</strong> potential <strong>to</strong> s<strong>to</strong>p <strong>the</strong> progression <strong>of</strong> <strong>osteoarthritis</strong> (Fig.4). Damaged<br />

chondrocytes produce inflamma<strong>to</strong>ry cy<strong>to</strong>kines that contribute <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> progression <strong>of</strong> OA through catabolic

<strong>nutrition</strong> myths and truths, facts and fallacies<br />

Physical Stress<br />

DOD<br />

Weight<br />

Trauma<br />

Structural &<br />

Functional<br />

Failure<br />

Cartilage<br />

Damage<br />

X<br />

Inflammation<br />

EPA<br />

X<br />

Matrix<br />

Damage<br />

Degradation caused<br />

by aggrecanases<br />

processes. Normally, arachidonic acid<br />

is <strong>the</strong> precursor for <strong>the</strong> syn<strong>the</strong>sis <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong>se inflamma<strong>to</strong>ry cy<strong>to</strong>kines. EPA,<br />

an omega-3 fatty acid, competes<br />

with arachidonic acid for <strong>the</strong> same<br />

enzyme systems; and <strong>the</strong> eicosanoids<br />

derived from EPA promote minimal <strong>to</strong><br />

no inflamma<strong>to</strong>ry activity. Thus, a diet<br />

containing n-3 fatty acids results in<br />

a decr<strong>ease</strong> in membrane arachidonic<br />

acid levels and an associated decr<strong>ease</strong><br />

in <strong>the</strong> pro-inflamma<strong>to</strong>ry cy<strong>to</strong>kines<br />

that perpetuate OA. Studies have<br />

documented that inflamma<strong>to</strong>ry<br />

eicosanoids produced from arachidonic<br />

acid are depressed when dogs consume<br />

foods with high levels <strong>of</strong> n-3 fatty acids, and specifically foods containing EPA. Though <strong>the</strong> exact molecular<br />

mechanisms for reducing inflammation (likely via resolvins and protectins) have not been fully explained, it is<br />

conceivable that omega-3 fatty acids modulate this process at <strong>the</strong> level <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> genome or proteome.<br />

Four randomized, double-masked, controlled studies have been conducted in which arthritic dogs were fed a<br />

control food or a test food containing various levels <strong>of</strong> EPA (omega-3 fatty acid). These studies reported that <strong>the</strong><br />

dogs fed <strong>the</strong> EPA-supplemented food improved in range <strong>of</strong> motion and ability <strong>to</strong> bear weight, had a decr<strong>ease</strong> in<br />

<strong>pain</strong> and lameness, had significantly improved ability <strong>to</strong> rise form a resting position, and improved ability <strong>to</strong> run<br />

and play at 6 weeks. In one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se studies, biomechanical force plate analysis was also performed and found<br />

that dogs fed a diet containing EPA had an incr<strong>ease</strong> in weight bearing on <strong>the</strong> affected limb. Only 31% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

“control” dogs had improved weight bearing after <strong>the</strong> 90-day feeding trial, whereas 82% <strong>of</strong> dogs in <strong>the</strong> “EPA”<br />

group showed incr<strong>ease</strong>d weight bearing. These clinical studies indicate that <strong>nutrition</strong>al management <strong>using</strong> a<br />

<strong>the</strong>rapeutic food supplemented with n-3 fatty acids helped improve <strong>the</strong> clinical signs <strong>of</strong> <strong>osteoarthritis</strong> in dogs as<br />

noted by pet owners, clinical orthopedic examination, and gait analysis <strong>of</strong> ground reaction forces.<br />

Dis<strong>ease</strong>-modifying <strong>osteoarthritis</strong> agents: These agents reportedly enhance cartilage health by providing<br />

<strong>the</strong> necessary precursors <strong>to</strong> maintain and repair cartilage. Many have been shown <strong>to</strong> positively affect cartilage<br />

matrix, enhance hyaluronate production, and inhibit catabolic enzymes. Oral dis<strong>ease</strong>-modifying OA agents<br />

typically contain glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate in various forms.<br />

Glucosamine is a precursor <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> disaccharide unit <strong>of</strong> glycosaminoglycans, which comprise <strong>the</strong> proteoglycan<br />

matrix <strong>of</strong> articular cartilage. Studies <strong>using</strong> radiolabeled compounds have shown that 87% <strong>of</strong> orally administered<br />

glucosamine is absorbed and is eventually incorporated in<strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> cartilage matrix. Glucosamine reportedly acts<br />

by providing <strong>the</strong> regula<strong>to</strong>ry stimulus and raw materials for syn<strong>the</strong>sis <strong>of</strong> glycosaminoglycans. Since chondrocytes<br />

obtain preformed glucosamine from <strong>the</strong> circulation (or syn<strong>the</strong>sizes it from glucose and amino acids), adequate<br />

glucosamine levels in <strong>the</strong> body are essential for syn<strong>the</strong>sis <strong>of</strong> glycosaminoglycans in cartilage. Glucosamine is also<br />

used directly for <strong>the</strong> production <strong>of</strong> hyaluronic acid by synoviocytes. In vitro biochemical and pharmacological<br />

studies indicate that <strong>the</strong> administration <strong>of</strong> glucosamine may normalize cartilage metabolism and stimulates<br />

<strong>the</strong> syn<strong>the</strong>sis <strong>of</strong> proteoglycans. Clinical trials in man and animals indicate that glucosamine may have a positive<br />

effect on cartilage health and helps control symp<strong>to</strong>ms associated with OA.<br />

X<br />

Figure 4: Pathophysiology <strong>of</strong> OA — In <strong>the</strong> dog, high levels <strong>of</strong> EPA help control<br />

pathways <strong>of</strong> inflammation and degradation.

<strong>nutrition</strong> myths and truths, facts and fallacies<br />

Chondroitin Sulfate (CS) is <strong>the</strong> predominant glycosaminoglycan found in articular cartilage. Bioavailability<br />

studies have shown 70% absorption <strong>of</strong> CS following oral administration. The effect <strong>of</strong> CS on cartilage has been<br />

investigated in several in vivo and in vitro studies. The findings suggest that CS reduces collagenolytic activity,<br />

inhibits degradative enzymes, incr<strong>ease</strong>s hyaluronate concentrations, and reduces symp<strong>to</strong>ms <strong>of</strong> OA. Most<br />

research indicates that glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate work synergistically. Numerous studies performed<br />

on one such combination (Cosequin ® Nutrimax Labora<strong>to</strong>ries, Inc.) have demonstrated improved syn<strong>the</strong>sis <strong>of</strong><br />

glycosaminoglycans and reduced proteolytic activity. Clinical trials have repeatedly shown a positive clinical<br />

effect in OA patients.<br />

Injectable dis<strong>ease</strong>-modifying OA agents are also available, <strong>the</strong> most common one used in dogs being Adequan ® *<br />

(used under license, Novartis Animal Health). Adequan is a polysulfated glycosaminoglycan (PSGAG), and studies<br />

have shown it has a positive anabolic effect on cartilage and decr<strong>ease</strong>s cartilage catabolism.<br />

Anti-inflamma<strong>to</strong>ry and analgesic medications (NSAIDs): NSAIDs are used because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir ability <strong>to</strong><br />

reduce joint <strong>pain</strong> and decr<strong>ease</strong> synovitis. A variety <strong>of</strong> NSAIDs are available for use in animals and are effective,<br />

in part, by decreasing prostaglandin syn<strong>the</strong>sis through <strong>the</strong> inhibition <strong>of</strong> cyclooxygenase (COX). Newer NSAIDs<br />

have been shown <strong>to</strong> have no detrimental affect on <strong>the</strong> syn<strong>the</strong>sis <strong>of</strong> cartilage proteoglycans in vitro at <strong>the</strong><br />

recommended dosing. Drugs commonly used <strong>to</strong> control <strong>pain</strong> in dogs with OA include acetaminophen (15 mg/<br />

kg q 8h), carpr<strong>of</strong>en (4.4 mg/kg q 24h), e<strong>to</strong>dolac (10-15 mg/kg q 24h), meloxicam (0.1 mg/kc q 8h), deracoxib<br />

(1-2 mg/kg q 24h), and tepoxalin (10mg/kg q 24h) among o<strong>the</strong>rs. It is important <strong>to</strong> recognize that individual<br />

patients respond <strong>to</strong> specific NSAIDs quite differently.<br />

Corticosteroid treatment for OA remains controversial. Corticosteroids decr<strong>ease</strong> <strong>the</strong> production <strong>of</strong> arachidonic<br />

acid, are potent anti-inflamma<strong>to</strong>ry agents, and decr<strong>ease</strong> catabolic activity within <strong>the</strong> joint. However,<br />

corticosteroids may also damage cartilage (with long-term usage) by decreasing syn<strong>the</strong>sis <strong>of</strong> collagen and<br />

matrix proteoglycans.<br />

Summary<br />

Although prevention <strong>of</strong> <strong>osteoarthritis</strong> is ideal, it is not always possible. Because <strong>osteoarthritis</strong> is a heterogeneous<br />

dis<strong>ease</strong> with diverse origins, it can present with a range <strong>of</strong> clinical manifestations. As a result, <strong>the</strong>rapeutic<br />

recommendations should be cus<strong>to</strong>mized for each patient. When appropriate, surgical correction <strong>of</strong> underlying<br />

conditions should be considered. After <strong>osteoarthritis</strong> is diagnosed, clients should be educated <strong>to</strong> foster<br />

realistic expectations. Osteoarthritis is usually irreversible but good management can minimize <strong>pain</strong> and slow<br />

progression <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> dis<strong>ease</strong>. The goals <strong>of</strong> management include:<br />

✔ mitigation <strong>of</strong> risk fac<strong>to</strong>rs<br />

✔ controlling clinical signs<br />

✔ slowing progression <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> dis<strong>ease</strong>.<br />

Thus, effective treatment requires a multimodal approach, <strong>of</strong> which <strong>the</strong>rapeutic <strong>nutrition</strong> is an important<br />

component. The goals <strong>of</strong> <strong>nutrition</strong>al management include reducing inflammation and <strong>pain</strong>, enhancing cartilage<br />

repair, slowing cartilage degradation and providing tangible improvement in clinical signs <strong>of</strong> <strong>osteoarthritis</strong>.<br />

Foods designed for patients with <strong>osteoarthritis</strong> should supply age-appropriate <strong>nutrition</strong> and specific nutrients<br />

that may help reduce inflammation and <strong>pain</strong>, slow <strong>the</strong> degradative process, complement prescribed medications<br />

and provide tangible improvement in clinical signs.<br />

* As with all drugs in this class, side effects involving <strong>the</strong> digestive system, kidneys or liver may occur. These are normally mild, but may be serious. Pet owners should<br />

discontinue <strong>the</strong>rapy and contact <strong>the</strong>ir veterinarian immediately if side effects occur. Evaluation for pre-existing conditions and regular moni<strong>to</strong>ring are recommended<br />

for pets on any medication, including Adequan. ® Use with o<strong>the</strong>r NSAIDs or corticosteroids should be avoided.

<strong>nutrition</strong> myths and truths, facts and fallacies<br />

Clinical Case:<br />

Nutritional management <strong>of</strong> <strong>osteoarthritis</strong><br />

Phoebe<br />

His<strong>to</strong>ry and clinical findings<br />

Phoebe, a 6-year-old neutered female Labrador retriever mix, was<br />

examined for rear limb lameness <strong>of</strong> two years duration. Clinical signs<br />

were mild <strong>to</strong> moderate in severity and included difficulty in rising<br />

from rest, limping, stiffness and reluctance <strong>to</strong> run, jump or play. No<br />

medications or supplements were being given by <strong>the</strong> owner. Phoebe<br />

weighed 75 pounds but was considered overweight with a body<br />

condition score <strong>of</strong> 4 on a 5-point scale. Phoebe was fed a low-calorie<br />

dry dog food but had access <strong>to</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r food sources for cats and dogs in<br />

<strong>the</strong> same household.<br />

Physical examination was normal except for <strong>the</strong> overweight body condition and orthopedic problems. A thorough<br />

orthopedic examination revealed <strong>the</strong> following abnormalities:<br />

✔ slight lameness at a walk<br />

✔ normal weight-bearing at rest but favors <strong>the</strong> left rear limb when walking<br />

✔ mild limitation in range <strong>of</strong> motion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> left hip joint<br />

✔ <strong>of</strong>fers mild resistance when <strong>the</strong> right rear limb is elevated but bears full weight on <strong>the</strong> left hind limb<br />

✔ mild <strong>pain</strong> is elicited upon palpation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> left hip joint.<br />

A complete blood count, serum biochemistry pr<strong>of</strong>ile and<br />

urinalysis were normal. Radiographs showed changes consistent<br />

with bilateral hip dysplasia and degenerative joint dis<strong>ease</strong> with<br />

<strong>the</strong> left cox<strong>of</strong>emoral joint more severely affected (Fig. 1).<br />

Questions<br />

Q. What are <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>rapeutic goals for managing patients with<br />

<strong>osteoarthritis</strong> or degenerative joint dis<strong>ease</strong> <strong>of</strong> hip joints?<br />

A. Therapeutic goals for managing chronic <strong>osteoarthritis</strong> or<br />

degenerative joint dis<strong>ease</strong> in <strong>the</strong> cox<strong>of</strong>emoral joints include:<br />

✔ Eliminating underlying causes (e.g., femoral head and<br />

neck excision for aseptic necrosis <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> femoral head)<br />

Figure 1: Radiographs consistent with<br />

bilateral hip dysplasia and degenerative<br />

joint dis<strong>ease</strong> with <strong>the</strong> left cox<strong>of</strong>emoral joint<br />

more severely affected.<br />

✔ Setting realistic treatment expectations with Phoebe’s<br />

owner<br />

✔ Enhancing Phoebe’s quality <strong>of</strong> life by reducing <strong>pain</strong>,<br />

maintaining or improving activity level and improving<br />

joint function<br />

✔ Slowing dis<strong>ease</strong> progression by modifying cartilage<br />

structure and function.

<strong>nutrition</strong> myths and truths, facts and fallacies<br />

Physical<br />

Rehabilitation<br />

NSAID<br />

Adjunct<br />

Multimodal<br />

Osteoarthritis<br />

Management<br />

Weight Control<br />

and Exercise<br />

EPA-rich<br />

Diet<br />

Figure 2: Multimodal management <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>osteoarthritis</strong><br />

Chondroprotectant<br />

Most animals with chronic <strong>osteoarthritis</strong> or degenerative joint dis<strong>ease</strong><br />

have irreversible changes with no opportunity <strong>to</strong> eliminate or cure<br />

<strong>the</strong> condition. This makes client education very important. Realistic<br />

expectations for both Phoebe’s owner and <strong>the</strong> veterinarian should<br />

acknowledge <strong>the</strong> facts that degenerative joint dis<strong>ease</strong> is controllable<br />

but not curable. A comprehensive multimodal management plan<br />

should focus on long-term <strong>pain</strong> management, altering dis<strong>ease</strong><br />

progression and improving Phoebe’s quality <strong>of</strong> life (Fig. 2).<br />

Q. How might <strong>the</strong> overweight body condition contribute <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

clinical problems in this dog?<br />

A. Osteoarthritis is <strong>of</strong>ten associated with abnormal forces acting on<br />

normal joints or normal forces acting on abnormal joints. Obesity<br />

may contribute <strong>to</strong> progression <strong>of</strong> degenerative joint dis<strong>ease</strong> and<br />

clinical signs by ca<strong>using</strong> excess physical stress on ei<strong>the</strong>r normal or<br />

abnormal joints. Additionally, recent studies have documented<br />

metabolic activity in adipose tissue that may be <strong>of</strong> equal or greater importance. Adipocytes secrete several<br />

hormones including leptin and adiponectin and produce a diverse range <strong>of</strong> proteins termed adipokines. Among<br />

<strong>the</strong> currently recognized adipokines are a growing list <strong>of</strong> media<strong>to</strong>rs <strong>of</strong> inflammation (Fig. 3). These adipokines<br />

are found in human and canine adipocytes. Production <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se proteins is incr<strong>ease</strong>d in obesity, suggesting<br />

that obesity is a state <strong>of</strong> chronic low-grade inflammation. Low-grade inflammation may contribute <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

pathophysiology <strong>of</strong> a number <strong>of</strong> dis<strong>ease</strong>s commonly associated with obesity including <strong>osteoarthritis</strong>. This might<br />

explain why relatively small reductions in body weight can result in significant improvement in clinical signs.<br />

IL-6<br />

IL-beta<br />

IGF-1<br />

PAI-1<br />

Leptin<br />

C 3<br />

Adipose Tissue<br />

Angiotensinogen<br />

TGF-b<br />

SAA<br />

TNF<br />

Adiponectin<br />

Resistin<br />

Figure 3. Adipocy<strong>to</strong>kines and inflamma<strong>to</strong>ry media<strong>to</strong>rs produced<br />

by adipocytes and adipocyte associated macrophages. C3,<br />

complement protein 3; IGF-1, insulin-like growth fac<strong>to</strong>r-1; IL,<br />

interleukin; PAI-1, plasminogen activa<strong>to</strong>r inhibi<strong>to</strong>r-1; SAA, serum<br />

amyloid A; TNF-a, tumor necrosis fac<strong>to</strong>r-a; TGF-b, transforming<br />

growth fac<strong>to</strong>r-b.<br />

Q. Could this condition have been prevented with<br />

proper <strong>nutrition</strong>al management?<br />

A. Large- and giant-breed dogs are at risk for<br />

developmental orthopedic dis<strong>ease</strong> including<br />

hip and elbow dysplasia, osteochondrosis and<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r conditions associated with joint instability<br />

or incongruity. Nutritional risk fac<strong>to</strong>rs for<br />

developmental orthopedic dis<strong>ease</strong> include excess<br />

energy, fat and calcium intake during growth. Use<br />

<strong>of</strong> foods specifically formulated for large breed<br />

puppies helps manage <strong>the</strong>se <strong>nutrition</strong>al risk fac<strong>to</strong>rs<br />

and ensure a normal, healthy growth rate. Obesity<br />

is recognized as a risk fac<strong>to</strong>r for development<br />

<strong>of</strong> degenerative joint dis<strong>ease</strong> in dogs; avoiding<br />

obesity can help reduce <strong>the</strong> incidence and severity<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>osteoarthritis</strong>. Recent studies have shown that<br />

when at-risk puppies were fed free choice during<br />

growth, <strong>the</strong>y exhibited an incr<strong>ease</strong>d incidence<br />

and severity <strong>of</strong> hip joint laxity and hip dysplasia<br />

compared <strong>to</strong> puppies fed in a restricted fashion. Over time, those dogs fed <strong>to</strong> maintain lean body condition<br />

throughout life exhibited reduced severity <strong>of</strong> <strong>osteoarthritis</strong> and a delayed need for medication compared <strong>to</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong>ir heavier siblings.

<strong>nutrition</strong> myths and truths, facts and fallacies<br />

Q. Outline a comprehensive nonsurgical management plan for Phoebe.<br />

A. Non-surgical management <strong>of</strong> <strong>osteoarthritis</strong> should focus on three main aspects:<br />

✔ Activity modification<br />

✔ Medications and supplements <strong>to</strong> modify joint <strong>pain</strong> and function<br />

✔ Nutritional management that emphasizes weight control and modifying joint inflammation<br />

and cartilage degradation.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> past, limiting activity levels in patients with <strong>osteoarthritis</strong> and degenerative joint dis<strong>ease</strong> was considered<br />

important. However, recent studies in human and veterinary patients with <strong>osteoarthritis</strong> have shown <strong>the</strong><br />

benefits <strong>of</strong> exercise including decr<strong>ease</strong>d <strong>pain</strong> scores, improved joint function scores and less use <strong>of</strong> analgesic<br />

medications. Today, veterinary specialists are recommending <strong>the</strong>rapeutic exercise as a way <strong>to</strong> improve quality <strong>of</strong><br />

life for dogs with chronic <strong>osteoarthritis</strong>. A variety <strong>of</strong> medications and supplements are available <strong>to</strong> manage <strong>pain</strong><br />

and joint function. Responses <strong>to</strong> medications and supplements vary considerably in patients with <strong>osteoarthritis</strong><br />

and specific products and doses need <strong>to</strong> be individually tailored for each dog.<br />

Figure 4. Uptake <strong>of</strong> omega-3 fatty acids by canine chondrocytes AlA, alphalinolenate;<br />

EPA, eicosapentaenoate; DHA, docosahexanoate; control, serum free<br />

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM). Caterson, B, Flannery CR, Hughes<br />

CE, et al. Mechanisms involved in cartilage proteoglycan catabolism. Matrix Biology<br />

2000;19(4):333-344.<br />

New information has been generated<br />

about canine <strong>osteoarthritis</strong> from in<br />

vitro studies with cartilage models<br />

and clinical studies in dogs with<br />

various forms <strong>of</strong> arthritis. In vitro<br />

cartilage studies have shown that<br />

canine chondrocyte membranes<br />

selectively s<strong>to</strong>re <strong>the</strong> omega-3 fatty<br />

acid EPA (eicosapentaenoic acid), and<br />

not o<strong>the</strong>r omega-3 fatty acids (Fig. 4).<br />

EPA is <strong>the</strong> most important fatty acid<br />

for helping manage inflammation in<br />

cartilage <strong>of</strong> dogs. EPA is also <strong>the</strong> only<br />

omega-3 fatty acid shown <strong>to</strong> inhibit<br />

activity <strong>of</strong> enzymes that degrade<br />

cartilage and helps turn <strong>of</strong>f <strong>the</strong> signal<br />

<strong>to</strong> make degradative enzymes (Fig. 5).<br />

Based on <strong>the</strong>se in vitro studies, clinical<br />

trials were performed in dogs with<br />

arthritis <strong>using</strong> Hill’s ® Prescription Diet ®<br />

j/d Canine, a food enhanced with<br />

levels <strong>of</strong> EPA much higher than those found in typical pet food and <strong>the</strong> only canned <strong>the</strong>rapeutic pet food<br />

in <strong>the</strong> <strong>osteoarthritis</strong> category. Hill’s ® Prescription Diet ® j/d Canine also contains <strong>the</strong> highest levels <strong>of</strong> <strong>to</strong>tal<br />

omega-3 fatty acids,* an omega-6 <strong>to</strong> omega-3 ratio less than 1.0, high carnitine levels, added glucosamine and<br />

chondroitin sulfate, added antioxidant nutrients and added lysolecithin. Feeding Hill’s ® Prescription Diet ® j/d <br />

Canine <strong>to</strong> dogs with arthritis resulted in higher serum EPA concentrations, significant improvements in clinical<br />

signs observed by pet owners, improved clinical assessments <strong>of</strong> arthritis by veterinarians and improved weight<br />

bearing on affected limbs as measured by force plate gait analysis. Many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> dogs in <strong>the</strong> studies were not<br />

receiving medications or supplements in conjunction with <strong>the</strong> food.<br />

* Data on file. Hill’s Pet Nutrition, Inc.

<strong>nutrition</strong> myths and truths, facts and fallacies<br />

Degradation<br />

begins with<br />

physical<br />

stress<br />

Degradation<br />

begins with<br />

physical<br />

stress<br />

functional<br />

Chondrocyte<br />

damage<br />

Chondrocyte<br />

damage<br />

High levels <strong>of</strong> omega-3<br />

and a low ratio <strong>of</strong><br />

omega-6 <strong>to</strong> omega-3<br />

interrupt<br />

inflammation<br />

Structural &<br />

failure<br />

Matrix<br />

damage<br />

Inflammation<br />

EPA interrupts<br />

degradation<br />

Degradation<br />

a. Up regulation <strong>of</strong> aggrecanase enzymes and<br />

inflamma<strong>to</strong>ry media<strong>to</strong>rs perpetuate cycle <strong>of</strong><br />

proteoglycan breakdown and matrix damage.<br />

b. Appropriate levels <strong>of</strong> EPA inhibit <strong>the</strong> up<br />

regulation <strong>of</strong> aggrecanase enzymes at <strong>the</strong> level <strong>of</strong><br />

mRNA and modulate <strong>the</strong> inflamma<strong>to</strong>ry response<br />

breaking <strong>the</strong> cycle <strong>of</strong> matrix damage.<br />

Figure 5. Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) interrupts <strong>the</strong> cycle <strong>of</strong> cartilage degradation and inflammation.<br />

Case management<br />

Hill’s ® Prescription Diet ® j/d Canine Dry pet food was dispensed for <strong>the</strong> owners <strong>to</strong> feed <strong>to</strong> Phoebe. The amount<br />

<strong>of</strong> food was calculated for an obese-prone animal. The owners were encouraged <strong>to</strong> deny Phoebe access <strong>to</strong><br />

o<strong>the</strong>r sources <strong>of</strong> dog and cat food in <strong>the</strong> same household. Controlled exercise was also encouraged <strong>using</strong> walks<br />

on a leash. Six weeks later <strong>the</strong> owner reported improvements in all clinical problems associated with arthritis<br />

and improvements in Phoebe’s overall personality. The improvements observed by <strong>the</strong> owner continued at<br />

<strong>the</strong> three-month recheck and no <strong>pain</strong> was elicited on palpation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> left hip joint by <strong>the</strong> veterinarian. These<br />

improvements were noted without concurrent use <strong>of</strong> medications or supplements. Body weight and body<br />

condition score remained <strong>the</strong> same so client education focused on <strong>the</strong> importance <strong>of</strong> weight management with<br />

appropriate reductions in food, limiting access <strong>to</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r pet food and incr<strong>ease</strong>d levels <strong>of</strong> exercise.<br />

Hill’s ® Prescription Diet ® j/d Canine is clinically proven <strong>to</strong>:<br />

• Improve mobility in as few as 21 days 1,2,4<br />

• Reduce <strong>pain</strong> in dogs with arthritis 2,3<br />

• Help dogs with arthritis walk, run, and play better, and climb stairs more easily 1,2,4<br />

• Help improve <strong>the</strong> quality <strong>of</strong> life <strong>of</strong> dogs suffering from arthritis 2,4<br />

Hill’s ® Prescription Diet ® j/d Canine product attributes:<br />

• High levels <strong>of</strong> EPA intercept <strong>the</strong> genetic signal that causes cartilage damage<br />

• Omega-3 fatty acids help <strong>to</strong> maintain joint health<br />

• High L-carnitine levels help <strong>to</strong> burn fat while maintaining lean muscle mass<br />

• Added glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate help <strong>to</strong> provide building blocks for cartilage repair<br />

• Improved taste and highly palatable <strong>nutrition</strong> help <strong>to</strong> improve compliance<br />

1<br />

Dose titration effects <strong>of</strong> omega-3 fatty acids fed <strong>to</strong> dogs with <strong>osteoarthritis</strong> (3-month feeding study), 2003. Unpublished data.<br />

2<br />

Cross AR, Roush JK, Renberg WC, et al. Effects <strong>of</strong> feeding omega-3 fatty acids on clinical signs and force plate analysis in dogs with <strong>osteoarthritis</strong> (3-month feeding study), 2004. Unpublished data.<br />

3<br />

A multi-center, practice-based study <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>rapeutic food and a nonsteroidal anti-inflamma<strong>to</strong>ry drug in dogs with <strong>osteoarthritis</strong> (3-month feeding study), 2004. Unpublished data.<br />

4<br />

Dodd CE, Fritsch DA, Allen TA, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids in canine <strong>osteoarthritis</strong>: a randomized, double-masked study (6-month feeding study), 2004. Unpublished data.

<strong>nutrition</strong> myths and truths, facts and fallacies<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

Thanks <strong>to</strong> Dr. James Roush <strong>of</strong> Kansas State University and Dr. Tara Enwiller <strong>of</strong> Gilbert, Arizona, for providing<br />

information about this patient.<br />

Bibliography<br />

Paster ER, LaFond E, Biery DN, et al. Estimates <strong>of</strong> prevalence <strong>of</strong> hip dysplasia in Golden Retrievers and<br />

Rottweilers and <strong>the</strong> influence <strong>of</strong> bias on published prevalence figures. Journal <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> American Veterinary<br />

Medical Association 2005;226(3):387-392.<br />

Harari J. Clinical evaluation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> osteoarthritic patient. Vet Clin N Am. 1997;27(4):725-734.<br />

May SA. Degenerative joint dis<strong>ease</strong> (Osteoarthritis, Osteoarthrosis, Secondary Joint Dis<strong>ease</strong>). In Houl<strong>to</strong>n JEF,<br />

Collinson RW (eds): Manual <strong>of</strong> Small Animal Arthrology. British Small Animal Veterinary Association. Iowa State<br />

University Press, 1994, p 62.<br />

Wener LL. Arthrocentesis and joint fluid analysis: Diagnostic applications in joint dis<strong>ease</strong>s <strong>of</strong> small animals.<br />

Compendium on Continuing Education. 1979;1:855-862.<br />

McLaughlin RM. Management <strong>of</strong> chronic osteoarthritic <strong>pain</strong>. Vet Clin North Am Sm Anim Pract. 2000;30:933-949.<br />

Goldring MB. The role <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> chondrocyte in <strong>osteoarthritis</strong>. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:1916-1926.<br />

Denko CW, Malemud CJ. Metabolic disturbances and synovial joint responses in <strong>osteoarthritis</strong>. Frontiers<br />

Bioscience. 1999;4:686-693.<br />

Martel-Pelletier J, Alaaeddine N, Pelletier JP. Cy<strong>to</strong>kines and <strong>the</strong>ir role in <strong>the</strong> pathophysiology <strong>of</strong> <strong>osteoarthritis</strong>.<br />

Frontiers Bioscience. 1999;4:694-703.<br />

Holderbaum D, Haqqi TM, Moskowitz RW. Genetics and <strong>osteoarthritis</strong>; exposing <strong>the</strong> iceberg. Arthritis Rheum.<br />

1999;42:397-405.<br />

Prockop DJ. Heritable <strong>osteoarthritis</strong>, diagnosis and possible modes <strong>of</strong> cell and gene <strong>the</strong>rapy. Osteoarthritis and<br />

Cartilage. 1999;7:354-366.<br />

Martel-Pelletier J. Pathophysiology <strong>of</strong> <strong>osteoarthritis</strong>. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 1999;7:371-373.<br />

Goldring MB. The role <strong>of</strong> cy<strong>to</strong>kines as inflamma<strong>to</strong>ry media<strong>to</strong>rs in <strong>osteoarthritis</strong>: Lessons from animal models.<br />

Conn Tissue Res. 1999;40:1-11.<br />

Bassler C, Henrotin Y, Franchiment P. In vitro evaluation <strong>of</strong> drugs proposed as chondroprotective agents. Int J<br />

Tissue React. 1992;14:231-241.<br />

Ben<strong>to</strong>n HP, Vasseur PB, Broderick-Villa GA, Koolpe M. Effect <strong>of</strong> carpr<strong>of</strong>en on sulfated glycosaminoglycan<br />

metabolism, protein syn<strong>the</strong>sis, and prostaglandin rel<strong>ease</strong> by cultured osteoarthritic canine chondrocytes. Am J<br />

Vet Res. 1997;58:286-292.<br />

Bucci, LR. Chondroprotective agents: glucosamine salts and chondroitin sulphate. Townsend Letter for Doc<strong>to</strong>rs,<br />

1994;Jan:52-54.<br />

Eisele I, Wood IS, German AJ, et al. Adipokine gene expression in dog adipose tissues and dog white adipocytes<br />

differentiated in primary culture. Hormone and Metabolic Research 2005;37(8):474-481.<br />

Tryahurn P, and Wood IS. Adipokines: inflammation and <strong>the</strong> pleiotropic role <strong>of</strong> white adipose tissue. The British<br />

Journal <strong>of</strong> Nutrition 2004;92(3):347-355.<br />

Burkholder WJ, Taylor L, Hulse DA. Weight loss <strong>to</strong> optimal body condition incr<strong>ease</strong>s ground reactive forces in<br />

dogs with <strong>osteoarthritis</strong> (abstract) , in Proceedings. Purina Nutrition Forum 2000:74.<br />

10

<strong>nutrition</strong> myths and truths, facts and fallacies<br />

Impellizeri JA, Tetrick MA, Muir P. Effect <strong>of</strong> weight reduction on clinical signs <strong>of</strong> lameness in dogs with hip<br />

<strong>osteoarthritis</strong>. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2000;216:1089-1091.<br />

Budsberg S, Bartges J, Schoenherr B, et al. Effects <strong>of</strong> different n6:n3 fatty acid diets on canine stifle<br />

<strong>osteoarthritis</strong> (abstract), in Proceedings. Veterinary Orthopedic Society Annual Conference 2001;28:40.<br />

Caterson B, Flannery CR, Hughes CE, et al. Mechanisms involved in cartilage proteoglycan catabolism. Matrix<br />

Biology 2000;19:333-344.<br />

Curtis CL, Hughes CE, Flannery CR, et al. n-3 fatty acids specifically modulate catabolic fac<strong>to</strong>rs involved in<br />

articular cartilage degradation. J Biol Chem 2000;275:721-724.<br />

Curtis CL, Rees SG, Cramp J, et al. Effects <strong>of</strong> n-3 fatty acids on cartilage metabolism. Proc Nutr Soc<br />

2002;61:381-389.<br />

Dodd CE. Multicenter clinical study on <strong>the</strong> effect <strong>of</strong> an investigational food containing elevated omega-3 fatty<br />

acids on canine <strong>osteoarthritis</strong> clinical signs. Final report. Hill’s Pet Nutrition Center, 2004.<br />

Hansen RA, Allen KGD, Pluhar EG, et al. N-3 fatty acids decr<strong>ease</strong> inflamma<strong>to</strong>ry media<strong>to</strong>rs in arthritic dogs<br />

(abstract), in Proceedings. FASEB 2003.<br />

Kealy RD, Olsson SE, Monti JL, et al. Effects <strong>of</strong> limited food consumption on <strong>the</strong> incidence <strong>of</strong> hip dysplasia in<br />

growing dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1992;201:857-863.<br />

Kealy RD, Lawler DF, Ballam JM, et al. Five-year longitudinal study on limited food consumption and<br />

development <strong>of</strong> <strong>osteoarthritis</strong> in cox<strong>of</strong>emoral joints <strong>of</strong> dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1997;210:222-225.<br />

Kealy RD, Lawler DF, Ballam JM, et al. Evaluation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> effect <strong>of</strong> limited food consumption on <strong>the</strong> radiographic<br />

evidence <strong>of</strong> <strong>osteoarthritis</strong> in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2000;217:1678-1680.<br />

11

<strong>nutrition</strong> myths and truths, facts and fallacies<br />

Ron McLaughlin, DVM, DVSc, DACVS, is Pr<strong>of</strong>essor and Chief <strong>of</strong> Small<br />

Animal Surgery and Head <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Department <strong>of</strong> Clinical Sciences at Mississippi<br />

State University College <strong>of</strong> Veterinary Medicine. His primary areas <strong>of</strong> interest<br />

include <strong>the</strong> clinical areas <strong>of</strong> surgery, orthopedics and lameness. His research<br />

interests include orthopedics, gait analysis and biomechanics.<br />

®/ Hill’s, Prescription Diet and j/d trademarks are owned by Hill’s Pet Nutrition Inc. Adequan is a registered trademark owned by Luitpold Pharmaceuticals, Inc.<br />

Cosequin is a registered trademark <strong>of</strong> Nutrimax Labora<strong>to</strong>ries, Inc. ©2008 Hill’s Pet Nutrition, Inc.<br />

12