Promoting livelihood opportunities for rural youth - IFAD

Promoting livelihood opportunities for rural youth - IFAD

Promoting livelihood opportunities for rural youth - IFAD

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

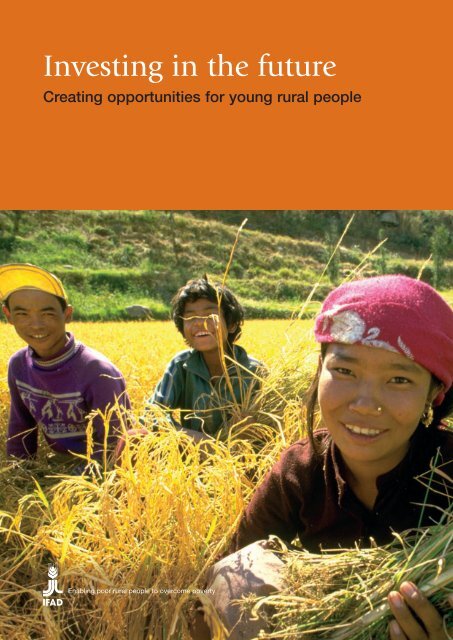

Investing in the future<br />

Creating <strong>opportunities</strong> <strong>for</strong> young <strong>rural</strong> people<br />

Enabling poor <strong>rural</strong> people to overcome poverty<br />

1

This paper was prepared by Paul Bennell, Senior Partner, Knowledge, Skills and<br />

Development, Brighton, UK, in consultation with Maria Hartl, Technical Adviser <strong>for</strong><br />

Gender and Social Equity in <strong>IFAD</strong>’s Policy and Technical Advisory Division.<br />

The following people reviewed the content: Annina Lubbock, Senior Technical Adviser<br />

<strong>for</strong> Gender and Poverty Targeting, Policy and Technical Advisory Division;<br />

Rosemary Vargas-Lundius, Senior Research Coordinator, Office of Strategy and<br />

Knowledge Management; and Philippe Remy, Country Programme Manager,<br />

West and Central Africa Division.<br />

The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily<br />

represent those of the International Fund <strong>for</strong> Agricultural Development (<strong>IFAD</strong>).<br />

The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do<br />

not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of <strong>IFAD</strong> concerning<br />

the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or<br />

concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The designations<br />

“developed” and “developing” countries are intended <strong>for</strong> statistical convenience and<br />

do not necessarily express a judgement about the stage reached by a particular<br />

country or area in the development process. This publication contains material that<br />

has not been subject to <strong>for</strong>mal review. It is circulated to stimulate discussion and<br />

critical comment.<br />

Cover:<br />

Young people harvest rice in the Wangdi area, Bhutan<br />

©<strong>IFAD</strong>/A. Hossain<br />

©2011 International Fund <strong>for</strong> Agricultural Development (<strong>IFAD</strong>)<br />

ISBN 978-92-9072-246-5<br />

August 2011<br />

2

Table of contents<br />

Introduction 4<br />

Who are <strong>rural</strong> <strong>youth</strong>? 8<br />

Key features of <strong>rural</strong> <strong>youth</strong> <strong>livelihood</strong>s 10<br />

Future labour demand in <strong>rural</strong> areas 12<br />

Improving <strong>youth</strong> <strong>livelihood</strong>s in <strong>rural</strong> areas 14<br />

Social capital and <strong>youth</strong> empowerment 16<br />

Human capital – basic education 17<br />

Human capital – skills training 18<br />

Financial capital – microfinance and enterprise development 20<br />

Public employment generation 23<br />

Partnerships to promote <strong>youth</strong> <strong>rural</strong> <strong>livelihood</strong>s 24<br />

Concluding remarks 26<br />

References 28<br />

Tables<br />

1 Youth unemployment rates by region 1999 and 2009 7<br />

Boxes<br />

1 EGMM in Andhra Pradesh 11<br />

2 The Rural Finance and Community Improvement Programme, Sierra Leone 17<br />

3 Farmer Field Schools in East Africa 18<br />

4 The San Francisco Agricultural School in Paraguay 19<br />

5 Employment creation <strong>for</strong> <strong>rural</strong> <strong>youth</strong> in NENA 21

Abbreviations and acronyms<br />

CIS<br />

EGMM<br />

EU<br />

FAO<br />

IFPRI<br />

ILO<br />

MDGs<br />

NENA<br />

PRSP<br />

SSA<br />

UWESO<br />

WDR<br />

YEN<br />

Commonwealth of Independent States<br />

Employment Generation and Marketing Mission<br />

European Union<br />

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations<br />

International Food Policy Research Institute<br />

International Labour Office<br />

Millennium Development Goals<br />

Near East and North Africa<br />

Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper<br />

Sub-Saharan Africa<br />

Uganda Women’s Ef<strong>for</strong>t to Save Orphans<br />

World Development Report<br />

Youth Employment Network<br />

3

Introduction<br />

This paper 1 reviews the situation of <strong>rural</strong><br />

<strong>youth</strong> in developing countries and presents<br />

options <strong>for</strong> improving their <strong>livelihood</strong>s in<br />

light of the many growing challenges they<br />

face. The main geographical focus is<br />

sub-Saharan Africa and the Near East and<br />

North Africa.<br />

Rural <strong>youth</strong> in developing countries make up<br />

a very large and vulnerable group that is<br />

seriously affected by the current international<br />

economic crisis. Globally, three-quarters of<br />

poor people live in <strong>rural</strong> areas, and about<br />

one-half of the population are young people.<br />

Climate change and the growing food crisis<br />

are also expected to have a disproportionately<br />

high impact on <strong>rural</strong> <strong>youth</strong>. The Food and<br />

Agriculture Organization of the United<br />

Nations (FAO) estimates that nearly half a<br />

billion <strong>rural</strong> <strong>youth</strong> “do not get the chance to<br />

realize their full potential” (FAO, 2009).<br />

The 2005 International Labour Organization<br />

(ILO) report on Global Employment Trends<br />

<strong>for</strong> Youth states: “today’s <strong>youth</strong> represent a<br />

group with serious vulnerabilities in the<br />

world of work. In recent years, slowing global<br />

employment growth and increasing<br />

unemployment, underemployment and<br />

disillusionment have hit young people<br />

hardest. As a result, today’s <strong>youth</strong> are faced<br />

with a growing deficit of decent work<br />

<strong>opportunities</strong> and high levels of economic<br />

and social uncertainty” (ILO, 2005).<br />

The lack of decent employment rather than<br />

open unemployment is the central issue in<br />

the majority of <strong>rural</strong> locations. In overall<br />

terms, four times as many young people earn<br />

less than US$2 a day than are unemployed.<br />

Youth are particularly vulnerable in conflict<br />

and post-conflict countries. Very high <strong>youth</strong><br />

unemployment coupled with rapid<br />

urbanization has fuelled civil conflict in<br />

many countries.<br />

It is widely recognized that smallholder<br />

agriculture and non-farm production in<br />

<strong>rural</strong> areas are among the most promising<br />

sectors <strong>for</strong> <strong>youth</strong> employment in the<br />

majority of developing countries. However,<br />

harnessing this potential remains an<br />

enormous challenge.<br />

While the crisis of ‘<strong>youth</strong> unemployment’<br />

(particularly in urban areas) has been a<br />

persistent concern of politicians and<br />

policymakers since the 1960s, <strong>youth</strong><br />

development has remained at the margins<br />

of national development strategies in most<br />

countries. We are now witnessing, however,<br />

a resurgence of interest in <strong>youth</strong>, the reasons<br />

<strong>for</strong> which stem from a growing realization<br />

of the seriously negative political, social and<br />

economic consequences stemming from the<br />

precariousness of <strong>youth</strong> <strong>livelihood</strong>s.<br />

For many, this amounts to a ‘<strong>youth</strong> crisis’,<br />

the resolution of which requires innovative,<br />

wide-ranging ‘<strong>youth</strong>-friendly’ policies and<br />

implementation strategies.<br />

1 The original version of this paper was shared as a<br />

background paper at the round table on “Generating<br />

remunerative <strong>livelihood</strong> <strong>opportunities</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>rural</strong> <strong>youth</strong>” at<br />

the Thirtieth Session of <strong>IFAD</strong>’s Governing Council held<br />

13-14 February 2007 in Rome, Italy. It has been revised to<br />

take into account the latest developments in this area,<br />

especially <strong>IFAD</strong> support <strong>for</strong> <strong>rural</strong> <strong>livelihood</strong> programming.<br />

4

A member of a local cooperative<br />

transplants seedlings in<br />

Ambalatenina village, Madagascar<br />

©<strong>IFAD</strong>/R. Ramasomanana

A worker packages decorative plants<br />

cultivated in a greenhouse, Loreto<br />

Corrientes, Argentina<br />

©<strong>IFAD</strong>/G. Bizzarri

The United Nations’ Millennium<br />

Development Goals (MDGs) single out <strong>youth</strong><br />

as a key target group. Target 16 of the MDGs<br />

is to develop and implement strategies <strong>for</strong><br />

decent and productive work <strong>for</strong> <strong>youth</strong>.<br />

The 2007 World Development Report<br />

published by the World Bank also focused<br />

on <strong>youth</strong>.<br />

The global population of young people aged<br />

12-24 is about 1.3 billion. The <strong>youth</strong><br />

population is projected to peak at 1.5 billion<br />

in 2035 and it will increase most rapidly in<br />

sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) and Southeast Asia<br />

(by 26 per cent and 20 per cent respectively<br />

between 2005 and 2035). FAO estimates that<br />

about 55 per cent of <strong>youth</strong>s reside in <strong>rural</strong><br />

areas, but this figure is as high as 70 per cent<br />

in SSA and South Asia. In SSA, young people<br />

aged 15-24 comprise 36 per cent of the entire<br />

labour <strong>for</strong>ce, 33 per cent in the Near East and<br />

North Africa (NENA), and 29 per cent in<br />

South Asia. About 85 per cent of the<br />

additional 500 million young people who<br />

will reach working age during the next decade<br />

live in developing countries. The global<br />

economic downturn has accelerated the<br />

growth of the <strong>rural</strong> <strong>youth</strong> population because<br />

many young migrants to urban areas are<br />

returning to their <strong>rural</strong> homes and other<br />

young people are discouraged from migrating<br />

to urban areas.<br />

Globally, <strong>youth</strong> are nearly three times<br />

more likely to be unemployed than adults<br />

(ILO, 2010). 2 However, the incidence of <strong>youth</strong><br />

unemployment varies considerably from one<br />

region to another. It is highest in the NENA<br />

region, where nearly one-quarter of all <strong>youth</strong><br />

are classified as being unemployed. It is<br />

lowest in East Asia and South Asia with rates<br />

of 9.0 per cent and 10.7 per cent respectively.<br />

Youth unemployment in sub-Saharan Africa<br />

was 12.6 per cent in 2009 (table 1).<br />

(Breakdowns of <strong>rural</strong> and urban <strong>youth</strong><br />

unemployment rates are not available.)<br />

Particularly high rates of <strong>youth</strong><br />

unemployment are closely linked with<br />

high rates of landlessness – <strong>for</strong> example,<br />

20 per cent in NENA.<br />

2 Young people aged 15-24 are estimated to account <strong>for</strong><br />

60 per cent of the unemployed in sub-Saharan Africa.<br />

TABLE 1<br />

Youth unemployment rates by region 1999 and 2009<br />

Region 1999 2009<br />

Developed economies and EU 13.9 17.7<br />

Central and Eastern Europe and CIS 22.7 21.5<br />

East Asia 9.2 9.0<br />

South East Asia and Pacific 13.1 15.3<br />

South Asia 9.8 10.7<br />

Latin America and the Caribbean 15.6 16.6<br />

Middle East 20.5 22.3<br />

North Africa 27.3 24.7<br />

Sub-Saharan Africa 12.6 12.6<br />

Source: ILO, Global Employment Trends, 2010.<br />

7

Who are <strong>rural</strong> <strong>youth</strong>?<br />

Age and location are the two key defining<br />

characteristics of <strong>rural</strong> <strong>youth</strong>. Age definitions<br />

of <strong>youth</strong> vary quite considerably. The United<br />

Nations defines <strong>youth</strong> as all individuals aged<br />

between 15 and 24. The 2007 World<br />

Development Report, which focuses on<br />

‘the next generation’, expands the definition<br />

of <strong>youth</strong> to include all young people aged<br />

between 12 and 14. Similar definitional<br />

variations exist with regard to location.<br />

Distinguishing between who is <strong>rural</strong> and who<br />

is urban is increasingly difficult, especially<br />

with the expansion of ‘peri-urban’ areas<br />

where large proportions of the population<br />

rely on agricultural activities to meet their<br />

<strong>livelihood</strong> needs.<br />

Traditionally, policy discussions concerning<br />

<strong>youth</strong> have been based on the premise that<br />

<strong>youth</strong> are in transition from childhood to<br />

adulthood and, as such, have specific<br />

characteristics that make them a distinct<br />

demographic and social category. This<br />

transition is multi-faceted. It involves the<br />

sexual maturation of individuals, their growing<br />

autonomy, and their social and economic<br />

independence from parents and other carers.<br />

The nature of the transition from childhood<br />

to adulthood has changed over time and<br />

varies considerably from one region to<br />

another. Rural children in developing<br />

countries become adults quickly mainly<br />

because the transition from school to work<br />

usually occurs at an early age and is<br />

completed in a short space of time. The same<br />

is true <strong>for</strong> poor young <strong>rural</strong> women with<br />

regard to marriage and childbearing. ‘Lack of<br />

alternatives’ is the major reason given <strong>for</strong> very<br />

high levels of marriage and childbearing<br />

among <strong>rural</strong> adolescent girls. Rural survival<br />

strategies demand that young people fully<br />

contribute to meeting the <strong>livelihood</strong> needs<br />

of their households from an early age.<br />

Consequently, <strong>youth</strong> as a transitional stage<br />

barely exists <strong>for</strong> the large majority of <strong>rural</strong><br />

<strong>youth</strong>, and the poor in particular. Many<br />

children aged 5-14 also work (<strong>for</strong> example,<br />

80 per cent in <strong>rural</strong> Ethiopia).<br />

Another related attribute of <strong>rural</strong> <strong>youth</strong> is that<br />

they tend to lack economic independence or<br />

‘autonomy’. The <strong>rural</strong> household is a joint<br />

venture, and the gender division of labour<br />

is such that full, individual control of the<br />

productive process is virtually impossible <strong>for</strong><br />

women in many countries. Given that large<br />

proportions of <strong>rural</strong> <strong>youth</strong> are subordinate<br />

members of usually large extended<br />

households, they are largely dependent on<br />

their parents <strong>for</strong> their <strong>livelihood</strong> needs.<br />

As <strong>youth</strong> grow older, the autonomy of males<br />

increases, but contracts <strong>for</strong> females. Moreover,<br />

in most traditional and poorest populations<br />

in low-income countries, girls typically marry<br />

shortly after menarche or when they leave school.<br />

Rural <strong>youth</strong> are also very heterogeneous.<br />

The World Bank definition of <strong>youth</strong><br />

encompasses the 12 year-old pre-pubescent<br />

boy attending primary school in a remote<br />

<strong>rural</strong> area and a 24-year old single mother of<br />

four children eking out an existence vending<br />

on the streets of a large <strong>rural</strong> village. Since<br />

8

their <strong>livelihood</strong> needs are markedly different,<br />

they require very different sets or ‘packages’<br />

of policy interventions. The same is true <strong>for</strong><br />

other distinct groups of <strong>rural</strong> disadvantaged<br />

<strong>youth</strong> including the disabled, ex-combatants<br />

and orphans. A clear separation also has to<br />

be made between school-aged <strong>youth</strong> and<br />

post-school <strong>youth</strong>. One of the main reasons<br />

<strong>youth</strong> programming has attracted such little<br />

support from governments, NGOs and donor<br />

agencies is that post-school <strong>youth</strong> are usually<br />

subsumed into the adult population as a<br />

whole. The implicit assumption is, there<strong>for</strong>e,<br />

that this group does not face any additional<br />

problems accessing the limited support<br />

services that are available <strong>for</strong> the adult<br />

population as a whole. Nor do they have any<br />

social and economic needs that relate<br />

specifically to their age that would<br />

give them priority over and above other<br />

economically excluded and socially<br />

vulnerable groups. The logical conclusion<br />

of this line of argument is that, given the<br />

limited relevance of <strong>youth</strong> as a distinct and<br />

protracted transitional phase in most <strong>rural</strong><br />

areas coupled with the heterogeneity of<br />

<strong>rural</strong> <strong>youth</strong>, <strong>youth</strong> may have limited<br />

usefulness as a social category around which<br />

major <strong>rural</strong> development policy initiatives<br />

should be developed.<br />

It is certainly the case that, with a few<br />

exceptions (such as South Africa), <strong>youth</strong> as<br />

a target group is not a major policy priority<br />

of most governments in low-income<br />

developing countries. Ministries of <strong>youth</strong><br />

are generally very poorly resourced and are<br />

usually subsumed with other government<br />

responsibilities, most commonly culture,<br />

sports and education. With regard<br />

to national poverty alleviation strategies,<br />

<strong>youth</strong> receives very little attention in most<br />

Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers (PRSPs).<br />

A 2005 overview of PRSPs conducted by the<br />

Economic Commission <strong>for</strong> Africa concluded<br />

that <strong>youth</strong> are still being overlooked.<br />

In particular, the chapters in PRSPs on<br />

agriculture rarely mention <strong>youth</strong>. Similarly,<br />

the standard chapter on ‘crosscutting’ issues<br />

focuses only on gender, environment and<br />

HIV/AIDS. In only two out of 12 PRSPs <strong>for</strong><br />

African countries that were reviewed <strong>youth</strong><br />

is singled out as a special group in<br />

mainstreaming employment, and, even<br />

in these exceptional cases, urban <strong>youth</strong> is<br />

of greater concern than <strong>rural</strong> <strong>youth</strong>. Even the<br />

World Development Report on <strong>youth</strong> (2007),<br />

devotes only four paragraphs to how to<br />

expand <strong>rural</strong> <strong>opportunities</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>youth</strong> and<br />

focuses mainly on <strong>rural</strong> non-farm activities.<br />

Only a relatively small number of recent<br />

<strong>IFAD</strong> projects specifically targeted <strong>youth</strong>.<br />

These projects were mainly concentrated<br />

in the NENA region, where levels of open<br />

unemployment among <strong>rural</strong> <strong>youth</strong> are<br />

particularly high. However, considerably<br />

more attention is now being given to <strong>youth</strong><br />

programming, with a particular focus on<br />

promoting <strong>youth</strong> employment through both<br />

farm and non-farm enterprise development.<br />

In the past, <strong>IFAD</strong> provided only limited<br />

funding <strong>for</strong> capacity development, especially<br />

skills training, <strong>for</strong> <strong>youth</strong> in agricultural<br />

activities. In part, this was because there is<br />

no specific education component in <strong>IFAD</strong>’s<br />

core mandate, although vocational training is<br />

offered across all agricultural specializations.<br />

<strong>IFAD</strong> is, however, becoming increasingly<br />

interested in providing support <strong>for</strong> targeted<br />

training <strong>for</strong> young farmers.<br />

9

Key features of <strong>rural</strong><br />

<strong>youth</strong> <strong>livelihood</strong>s<br />

Most <strong>rural</strong> <strong>youth</strong> are either employed<br />

(waged and self-employed) or not in the<br />

labour <strong>for</strong>ce. The issue, there<strong>for</strong>e, is not so<br />

much about unemployment, but serious<br />

under-employment in low productivity,<br />

predominantly household-based activities.<br />

The ILO estimates that about 300 million<br />

<strong>youth</strong>s (one-quarter of the total) live on less<br />

than US$2 a day. The unemployed are mainly<br />

better educated urban <strong>youth</strong> who can af<strong>for</strong>d<br />

to engage in relatively protracted job searches.<br />

It is better, there<strong>for</strong>e, to focus on improving<br />

the <strong>livelihood</strong>s of the most disadvantaged<br />

<strong>youth</strong> rather than those who are unemployed.<br />

Access to key productive assets, particularly<br />

land, is a critical issue <strong>for</strong> young people.<br />

It is often argued (although usually not<br />

based on robust evidence) that <strong>rural</strong> <strong>youth</strong><br />

are increasingly disinterested in smallholder<br />

farming and tend to travel nationally and,<br />

increasingly, across international borders,<br />

in search of employment.<br />

This exodus of young people from <strong>rural</strong> areas<br />

is resulting in a marked ageing of the <strong>rural</strong><br />

population in some countries. In some<br />

provinces in China, <strong>for</strong> example, the average<br />

age of farmers is 45-50 years. Recent research<br />

shows that migration from <strong>rural</strong> to urban<br />

areas will continue on a large scale, and that<br />

this is an essential part of the <strong>livelihood</strong><br />

coping strategies of poor <strong>rural</strong> people.<br />

Temporary migration and commuting are<br />

also a routine part of the combined<br />

<strong>rural</strong>-urban <strong>livelihood</strong> strategies of poor<br />

people across a wide range of developing<br />

countries (Deshingkar, 2004). In many parts<br />

of Asia and Africa, remittances from <strong>rural</strong> to<br />

urban migration are overtaking the income<br />

from agriculture. It is important, there<strong>for</strong>e,<br />

that young people in <strong>rural</strong> areas are prepared<br />

<strong>for</strong> productive lives in both <strong>rural</strong> and urban<br />

environments. Policymakers should, in turn,<br />

revise negative perceptions of migration and<br />

view migration as socially and economically<br />

desirable (see box 1).<br />

10

BOX 1<br />

EGMM in Andhra Pradesh<br />

The Employment Generation and Marketing Mission (EGMM), which was established by the Andhra<br />

Pradesh state government in India, is a good example of a successful, pro-migration employment<br />

generation scheme <strong>for</strong> <strong>rural</strong> <strong>youth</strong>. It relies on an extensive network of 800,000 self-help groups that<br />

works closely with the business community to help <strong>rural</strong> <strong>youth</strong> find <strong>for</strong>mal-sector employment.<br />

Rural academies provide short high-quality, focused training courses in retail, security, English, work<br />

readiness and computers. Youth trained in the programme earn about three to four times the<br />

income of a <strong>rural</strong> farm household in the state.<br />

Rural <strong>youth</strong> tend to be poorly educated,<br />

especially in comparison with urban <strong>youth</strong>.<br />

The extent of ‘urban bias’ in the provision<br />

of publicly funded education and training<br />

services is large in most low-income<br />

developing countries (see Bennell, 1999).<br />

The deployment of teachers and other key<br />

workers to <strong>rural</strong> areas amounts to nothing<br />

less than a crisis in many countries. Poor<br />

quality education, high (direct and indirect)<br />

schooling costs, and the paucity of ‘good<br />

jobs’ continue to dampen the demand <strong>for</strong><br />

education among poor parents.<br />

Rural <strong>youth</strong> have been heavily involved<br />

in civil wars, and other <strong>for</strong>ms of conflict<br />

in a growing number of countries, which<br />

poses a major threat to the long-term<br />

development prospects of these countries.<br />

Traditional safety nets are breaking down<br />

and <strong>rural</strong> <strong>youth</strong> expectations <strong>for</strong> a better life<br />

are increasing, especially with access to global<br />

in<strong>for</strong>mation technologies.<br />

Rural <strong>youth</strong> face major health problems,<br />

including malnutrition, malaria and<br />

HIV/AIDS. It is important, however, to keep<br />

the direct health threat posed by HIV/AIDS<br />

in proper perspective. Except <strong>for</strong> a handful<br />

of very high prevalence countries,<br />

HIV prevalence among <strong>rural</strong> teenagers<br />

remains very low. In very large countries in<br />

sub-Saharan Africa such as Ethiopia, Nigeria,<br />

the Democratic Republic of the Congo and<br />

all of Asia and Central and South America,<br />

the incidence of HIV infection among <strong>rural</strong><br />

teenagers is well under one per cent.<br />

The main impact of the AIDS epidemic on<br />

<strong>rural</strong> <strong>youth</strong> <strong>livelihood</strong>s is the rapidly growing<br />

number of children and <strong>youth</strong> whose parents<br />

have died from AIDS-related illnesses.<br />

As with the <strong>rural</strong> population as a whole,<br />

<strong>rural</strong> <strong>youth</strong> are engaged in a diverse range<br />

of productive activities, both agricultural and<br />

non-agricultural. Statistics are limited, but the<br />

proportions of <strong>rural</strong> <strong>youth</strong> engaged in waged<br />

and self-employment in both these main areas<br />

of activity varies considerably across countries.<br />

The lack of access to basic infrastructure in<br />

<strong>rural</strong> areas is also a key issue. In the majority<br />

of countries in SSA, less than 10 per cent of<br />

<strong>rural</strong> households have access to electricity and<br />

less than half have access to drinking water<br />

within 15 minutes of their homes.<br />

The impact on <strong>youth</strong> can be particularly<br />

severe. For example, girls and young<br />

women are usually responsible <strong>for</strong> water<br />

collection, and the lack of electricity<br />

seriously limits training and other<br />

employment creation <strong>opportunities</strong>.<br />

11

Future labour demand<br />

in <strong>rural</strong> areas<br />

Over the coming decades, there will be much<br />

debate and uncertainty about the roles and<br />

contributions of the agricultural and <strong>rural</strong><br />

non-farm sectors in the development process.<br />

It is impossible, there<strong>for</strong>e, to make robust<br />

projections of future labour demand in <strong>rural</strong><br />

areas. Rural reality is changing fast in many<br />

countries. Agriculture is increasingly<br />

sophisticated and commercial, and a<br />

growing share of <strong>rural</strong> incomes comes from<br />

the non-farm economy. Many poor <strong>rural</strong><br />

people are part-time farmers or are landless.<br />

It is widely recognized that <strong>rural</strong> diversification<br />

will be the lynchpin of successful agricultural<br />

trans<strong>for</strong>mation in the future. Where <strong>rural</strong><br />

diversification is not economically feasible, the<br />

alternative will be the transition of economic<br />

activity from <strong>rural</strong> to urban areas. Whatever the<br />

outcome, <strong>rural</strong> <strong>youth</strong> will be at the <strong>for</strong>efront<br />

of this process of change.<br />

Rural non-farm activities account <strong>for</strong> a large<br />

and growing share of employment and<br />

income, especially among the poor and<br />

women who lack key assets, most notably<br />

land. The <strong>rural</strong> non-farm sector is seen as the<br />

‘ladder’ from under employment in lowproductivity<br />

smallholder production to<br />

regular wage employment in the local<br />

economy and from there to jobs in the<br />

<strong>for</strong>mal sector. The key policy goals <strong>for</strong> the<br />

<strong>rural</strong> non-farm sector are to identify the key<br />

engines of growth, focus on sub sectorspecific<br />

supply chains, and build flexible<br />

institutional coalitions of public and private<br />

agencies (see Haggblade et al 2002).<br />

Traditionally, manpower planners have<br />

assumed that increased demand <strong>for</strong> labour<br />

in a particular sector, such as smallholder<br />

agriculture, depends on the projected rate<br />

of growth of output and the elasticity of<br />

employment with respect to output <strong>for</strong> that<br />

specific sector. However, in countries without<br />

unemployment benefit systems, these<br />

assumptions generally do not apply. 3<br />

Consequently, an increase in the demand<br />

<strong>for</strong> labour is reflected in an increase in the<br />

quality rather than the quantity of<br />

employment: workers move from unpaid to<br />

wage jobs, from worse jobs to better jobs, etc.<br />

Subsistence agriculture and in<strong>for</strong>mal sectors<br />

are ‘sponges’ <strong>for</strong> surplus labour. Also, the<br />

traditional manpower planning analysis sets<br />

up a false conflict between increasing<br />

productivity and increasing employment.<br />

It leads employment planners to talk about<br />

the threat posed to jobs of too fast growth in<br />

productivity, whereas the process is entirely the<br />

opposite. Increasing productivity is at the centre<br />

stage <strong>for</strong> any strategy to increase the quality of<br />

employment (Godfrey, 2005 and 2006).<br />

Growth in productive-sector wage<br />

employment is a source of dynamism in the<br />

labour market as a whole. When wage<br />

employment increases, the self-employed in<br />

both <strong>rural</strong> and urban areas, also face less<br />

competition <strong>for</strong> assets and customers and enjoy<br />

an increase in the demand <strong>for</strong> their products.<br />

3 This is because total employment is largely supply<br />

determined and employment elasticities of demand tend to<br />

vary inversely with output growth.<br />

12

The regions that have been most successful<br />

recently in increasing demand <strong>for</strong> labour and<br />

reducing the incidence of poverty are those<br />

where the share of productive-sector wage<br />

earners in total employment has been rising.<br />

Unless demand <strong>for</strong> labour is expanding it is<br />

very difficult to design and implement<br />

programmes to increase the integrability<br />

of disadvantaged <strong>youth</strong>.<br />

Boosting labour demand will depend on<br />

promoting growth sectors in the <strong>rural</strong><br />

economy in line with dynamic comparative<br />

advantage (which will be natural resourcebased<br />

in most countries) supported by an<br />

appropriate macroeconomic policy framework.<br />

Young women collect water,<br />

Dan Bako village, the Niger<br />

©<strong>IFAD</strong>/D. Rose

Improving <strong>youth</strong> <strong>livelihood</strong>s<br />

in <strong>rural</strong> areas<br />

A clear distinction should be made between,<br />

on the one hand, social and economic<br />

policies that are not specifically targeted at<br />

<strong>youth</strong>, but nonetheless benefit <strong>youth</strong>, either<br />

directly or indirectly, and, on the other hand,<br />

<strong>youth</strong>-specific policies that do target <strong>youth</strong><br />

as a whole or groups of <strong>youth</strong>. It is widely<br />

alleged that <strong>youth</strong> development is at the<br />

periphery of the development agenda in most<br />

countries. And yet, given that <strong>youth</strong> comprise<br />

such a large proportion of the <strong>rural</strong> labour<br />

<strong>for</strong>ce, most development projects and<br />

programmes in <strong>rural</strong> areas do promote <strong>youth</strong><br />

<strong>livelihood</strong>s to a large extent. Youth is the<br />

primary client group <strong>for</strong> education and training<br />

programmes as well as health and health<br />

prevention activities. Even so, participatory<br />

assessments often show that <strong>rural</strong> communities<br />

want more <strong>youth</strong>-focused activities.<br />

The 2007 World Development Report (WDR)<br />

on <strong>youth</strong> concludes that <strong>youth</strong> policies often<br />

fail. Youth policies in developing countries<br />

have frequently been criticized <strong>for</strong> being<br />

biased towards non-poor, males living in<br />

urban areas. Given the paucity of <strong>youth</strong><br />

support services in many countries, they<br />

tend to be captured by non-poor <strong>youth</strong>.<br />

For example, secondary school-leavers in<br />

SSA have increasingly taken over <strong>rural</strong><br />

training centres originally meant <strong>for</strong> primary<br />

school-leavers and secondary school<br />

dropouts. National <strong>youth</strong> service schemes<br />

enrol only university graduates and<br />

occasionally secondary school leavers,<br />

most of who are neither poor or from <strong>rural</strong><br />

areas. Many schemes have been scrapped during<br />

the last given deepening fiscal crises coupled<br />

with the relatively high costs of these schemes.<br />

The World Bank’s 2007 global inventory<br />

of interventions to support young workers is<br />

based on 289 documented projects and other<br />

interventions in 84 countries. However, only<br />

13 per cent of the projects were in SSA and<br />

NENA and less than 10 per cent of<br />

interventions were targeted exclusively in<br />

<strong>rural</strong> areas. Two other notable findings are<br />

the predominance of skills training<br />

interventions and the very limited robust<br />

evidence available on project outcomes and<br />

impacts (Betcherman et al, 2007).<br />

A common misconception of <strong>youth</strong> policy<br />

has been that boys and girls are a<br />

homogeneous group. Uncritical focusing on<br />

<strong>youth</strong> could, there<strong>for</strong>e, divert attention away<br />

from the gender agenda since female and<br />

male <strong>youth</strong> often have conflicting interests.<br />

Rural adolescent girls are virtually trapped<br />

within the domestic sphere in many<br />

countries. Because boys spend more time<br />

in productive activities that generate income,<br />

they are more visible and are more likely,<br />

there<strong>for</strong>e, to be supported.<br />

Sexual reproductive health issues have<br />

increasingly dominated <strong>youth</strong> policy during<br />

the last decade. Up to the 1990s, the main<br />

preoccupation of governments and donors was<br />

to reduce <strong>youth</strong> fertility rates (through later<br />

marriage and smaller families). Since then, the<br />

focus (in at least in SSA) has shifted to reducing<br />

the risks of HIV infection among <strong>youth</strong>.<br />

14

Children harvest lotus flowers<br />

in Galgamuwa, Sri Lanka<br />

©<strong>IFAD</strong>/G.M.B. Akash<br />

At the most general level, <strong>youth</strong> employment<br />

policies should focus on (i) increasing the<br />

demand <strong>for</strong> labour in relation to supply;<br />

and (ii) increasing the ‘integrability’ of<br />

disadvantaged <strong>youth</strong> so that they can take<br />

advantage of labour market and other<br />

economic <strong>opportunities</strong> when they arise.<br />

There are three main aspects of <strong>youth</strong><br />

integration namely, remedying or<br />

counteracting market failure (labour, credit,<br />

location, training systems), optimizing labour<br />

market regulations, and improving the skills<br />

of disadvantaged <strong>youth</strong>.<br />

There is a fairly standard list of policy<br />

interventions to improve the <strong>livelihood</strong>s<br />

of <strong>rural</strong> <strong>youth</strong> that are enumerated in policy<br />

discussions as well as in policy documents<br />

and the academic literature. The United<br />

Nation’s World Programme of Action <strong>for</strong><br />

Youth, which was originally promulgated<br />

in 1995, identifies the following ‘fields of<br />

action’: education, employment, hunger<br />

and poverty, health, environment, drug<br />

abuse, juvenile delinquency and leisure.<br />

Youth <strong>livelihood</strong> improvement programmes<br />

typically distinguish between interventions<br />

that improve capabilities and resources<br />

(especially education, health, ‘life skills’,<br />

training and financial services/credit) and<br />

those that structure <strong>opportunities</strong> (individual<br />

and group income generation activities,<br />

promoting access to markets, land,<br />

infrastructure and other services), the<br />

protection and promotion of rights and the<br />

development of <strong>youth</strong> institutions.<br />

There is also increasing awareness of the<br />

inter-relatedness and linkages between<br />

different kinds of interventions <strong>for</strong> <strong>youth</strong>.<br />

In particular, in the context of the AIDS<br />

epidemic, it is contended that improved<br />

<strong>youth</strong> <strong>livelihood</strong>s may reduce the incidence<br />

of high-risk ‘transactional’ sexual<br />

relationships, which are mainly motivated by<br />

material gain (the ‘sex-<strong>for</strong>-food, food-<strong>for</strong>-sex’<br />

syndrome). Integrated programming is,<br />

there<strong>for</strong>e, desirable, but is complicated, both<br />

with to programme design and implementation.<br />

15

According to the sustainable <strong>livelihood</strong>s<br />

approach, the <strong>livelihood</strong> ‘capital assets’ of<br />

<strong>rural</strong> <strong>youth</strong> can be broken down into the<br />

following four main types: political and<br />

social, physical and natural, human and<br />

financial. A wide range of <strong>livelihood</strong><br />

improvement interventions has been<br />

undertaken with respect to these asset types.<br />

<strong>IFAD</strong>’s core mandate focuses mainly on<br />

strengthening the productive base of <strong>rural</strong><br />

households and, as such, is most directly<br />

related to interventions that improve physical<br />

and natural and financial assets as well as jobrelated<br />

human capital through skills training.<br />

The available evidence strongly suggests that<br />

comprehensive multiple services approaches<br />

(such as the Jovenes programmes in South<br />

America) are more effective than fragmented<br />

interventions <strong>for</strong> generating sustainable<br />

employment <strong>opportunities</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>youth</strong>. However,<br />

such approaches are relatively expensive, which<br />

continues to limit their applicability in most<br />

low-income developing countries.<br />

Social capital and <strong>youth</strong> empowerment<br />

Youth, especially in <strong>rural</strong> areas, do not<br />

usually constitute an organized and vocal<br />

constituency with the economic and social<br />

power to lobby on their own behalf.<br />

Consequently, empowering <strong>rural</strong> <strong>youth</strong> to<br />

take an active role in agriculture and <strong>rural</strong><br />

development is critical. Successful <strong>youth</strong><br />

policies also depend on effective<br />

representation by <strong>youth</strong>. Traditionally, despite<br />

their size, <strong>rural</strong> <strong>youth</strong> have had limited social<br />

and political power. Older people, and<br />

especially older males, tend to dominate<br />

decision-making at all levels in <strong>rural</strong> societies.<br />

In SSA, some writers refer to this as a<br />

gerontocracy. The subordinate position of<br />

<strong>youth</strong> has been further compounded by the<br />

traditional welfare approach – <strong>youth</strong> are<br />

viewed as presenting problems that need to<br />

be solved through the intervention of older<br />

people. It is now widely accepted, however,<br />

that <strong>youth</strong> can play a major role in improving<br />

governance nationally and locally, and in<br />

implementing key economic and social<br />

policies. In particular, <strong>rural</strong> <strong>youth</strong> should be<br />

at the <strong>for</strong>efront of ef<strong>for</strong>ts to broaden<br />

<strong>opportunities</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>rural</strong> people. Urban bias<br />

with respect to macro-, sector- and meso-level<br />

policies and related resource allocations is<br />

also likely to become even more acute as the<br />

problems in urban areas increase and needs<br />

to be countered. Well-designed interventions<br />

are required to build up the political and<br />

social capital of <strong>rural</strong> <strong>youth</strong>. Youth have to<br />

be mobilized so that they are able to<br />

participate fully and gain ownership over<br />

<strong>youth</strong> development strategies and policies.<br />

This becomes even more challenging <strong>for</strong><br />

young people who are under 18 and who are,<br />

there<strong>for</strong>e, still considered to be children.<br />

New ways of working with young people<br />

in <strong>rural</strong> areas are being pioneered in many<br />

countries. Rural <strong>youth</strong> organizations and<br />

networks should be established and<br />

strengthened. There are many exciting<br />

developments in this area. For example, the<br />

<strong>IFAD</strong>-funded Rural Youth Talents Programme<br />

in South America is based on a new strategy<br />

that seeks to systematize and publicize the<br />

experiences and lessons learned from <strong>rural</strong><br />

<strong>youth</strong> programming. The ILO-supported<br />

Youth-to-Youth Fund in Cote d’Ivoire, Guinea,<br />

Liberia, Sierra Leone and three East African<br />

countries (Kenya, Uganda and the United<br />

Republic of Tanzania) also demonstrates how<br />

<strong>youth</strong>-led organizations can effectively<br />

promote <strong>rural</strong>-based farming and non-farming<br />

enterprises. The Mercy Corps Youth<br />

Trans<strong>for</strong>mation Framework has adopted a<br />

similar approach in 40 fragile environment<br />

countries. Community Action Plans have been<br />

successfully piloted in Jordan, which map<br />

<strong>youth</strong> <strong>livelihood</strong> <strong>opportunities</strong> with the<br />

greatest potential and foster an entrepreneurial<br />

mindset with a strong focus on life-skills<br />

training. The provision of financial services<br />

<strong>for</strong> <strong>rural</strong> <strong>youth</strong> in Sierra Leone is another<br />

pioneering initiative (see box 2).<br />

16

BOX 2<br />

The Rural Finance and Community Improvement Programme,<br />

Sierra Leone<br />

The objective of this initiative is to help poor <strong>rural</strong> people, especially <strong>youth</strong>, gain access to<br />

financial services by establishing financial services associations. Each <strong>for</strong>mally registered<br />

association enables <strong>rural</strong> communities to access a comprehensive range of financial services.<br />

It capitalizes on in<strong>for</strong>mal local rules, customs, relationships, local knowledge and solidarity, while<br />

introducing <strong>for</strong>mal banking concepts and methods. The current associations are wholly managed<br />

by young people. Each association has a manager and a cashier selected by the programme from<br />

the local community.<br />

Human capital – basic education<br />

Nearly 140 million <strong>youth</strong>s in developing<br />

countries are classified as ‘illiterate’. More<br />

generally, the preparation of <strong>rural</strong> <strong>youth</strong> <strong>for</strong><br />

productive work is poor (see Atchorarena and<br />

Gasperini, 2009). According to the 2007<br />

World Development Report, ‘changing<br />

circumstances’ mean that much greater<br />

attention needs to be given to the human<br />

capital needs of <strong>youth</strong>. These “include new<br />

health risks, the changing nature of politics<br />

and the growth of civil society, globalization<br />

and new technologies, expansion in access to<br />

basic education and the rising demand <strong>for</strong><br />

workers with higher education”.<br />

There is no simple, direct link between<br />

education and employment. However, the<br />

best way to improve the future employment<br />

and <strong>livelihood</strong> prospects of disadvantaged<br />

young people in both <strong>rural</strong> and urban areas<br />

is to ensure that they stay in school until they<br />

are least functionally literate and numerate.<br />

Expanding girl’s education is the most<br />

obvious lever to change the situation of<br />

young women. In the majority of low-income<br />

developing countries, however, <strong>rural</strong> <strong>youth</strong><br />

still do not acquire these basic competencies.<br />

In Ethiopia, <strong>for</strong> example, nearly threequarters<br />

of 15-24 year olds have no<br />

schooling. In SSA and South Asia more<br />

than one-third of <strong>youth</strong> were still classified as<br />

illiterate in 2002. The availability of primary<br />

schooling in <strong>rural</strong> areas is improving rapidly<br />

in many countries, but the quality of<br />

education remains generally very low and<br />

is even declining in some countries.<br />

There are also major concerns about<br />

the relevance of schooling in <strong>rural</strong> areas.<br />

Curricula are criticized <strong>for</strong> not adequately<br />

preparing children <strong>for</strong> productive <strong>rural</strong> lives<br />

and, worse still, fueling <strong>youth</strong> aspirations to<br />

move to urban areas. Calls persist <strong>for</strong> the<br />

vocationalization of schooling in <strong>rural</strong> areas,<br />

despite the fact that previous initiatives to<br />

do so have failed in most countries <strong>for</strong><br />

both supply and demand-side reasons.<br />

Governments and other providers should,<br />

there<strong>for</strong>e, focus on delivering reasonable<br />

quality basic education. The current push <strong>for</strong><br />

eight years of universal basic education in<br />

most countries means that most children will<br />

not complete their schooling until they are<br />

15-16 years old.<br />

17

BOX 3<br />

Farmer Field Schools in East Africa<br />

FAO, other UN agencies and NGOs are supporting the establishment of Farmer Field Schools in<br />

East Africa. The schools combine FAO’s popular Farmer Field School teaching methodology, which<br />

is designed to teach adult farmers about the ecology of their fields through first-hand observation<br />

and analysis, and the Farmer Life School, which uses similar analytical techniques to teach human<br />

behaviour and AIDS prevention.<br />

A recently conducted comprehensive impact evaluation of Farmer Field Schools in Kenya, Uganda<br />

and the United Republic of Tanzania by a team from the International Food Policy Research Institute<br />

(IFPRI) concluded that participation increased income by 61 per cent across the three countries as<br />

a whole. The most significant change was <strong>for</strong> crop production in Kenya (80 per cent increase) and<br />

in the United Republic of Tanzania <strong>for</strong> agricultural income (more than a 100 per cent increase).<br />

The main reason <strong>for</strong> these positive impacts is that adoption of new agricultural technologies and<br />

innovations is significantly higher among farmers who attend the schools. Another key finding is<br />

that younger farmers are more likely to participate in the schools than older farmers in all three<br />

countries and that female-headed households benefited significantly more than male-headed<br />

households in Uganda (Davis, 2009).<br />

Given the endemic problems of <strong>rural</strong><br />

schooling with high drop-out rates, support<br />

<strong>for</strong> non-<strong>for</strong>mal education programmes has<br />

increased considerably during the last decade.<br />

For example, Morocco’s Second Chance<br />

schools target 2.2 million children between<br />

8 and 16 years old who have never attended<br />

school or have not completed the full<br />

primary cycle. More than three-quarters of<br />

this group live in <strong>rural</strong> areas and about<br />

45 per cent are girls. The Bangladesh Rural<br />

Advancement Committee model of non<strong>for</strong>mal<br />

education is now being replicated in<br />

a number of countries, including several<br />

in sub-Saharan Africa.<br />

Human capital – skills training<br />

The <strong>rural</strong> world is changing rapidly in most<br />

countries. Rural <strong>youth</strong> must, there<strong>for</strong>e, be<br />

equipped with the requisite skills to exploit<br />

new <strong>opportunities</strong>. However, the provision of<br />

good quality post school skills training (both<br />

pre-employment and job-related) remains<br />

very limited in most <strong>rural</strong> areas. The key issue<br />

in many countries is that national vocational<br />

training systems have been unable to deliver<br />

good quality and cost-effective training to<br />

large numbers of both school leavers and the<br />

currently employed. It is essential, there<strong>for</strong>e,<br />

that all training is based on precise assessments<br />

of job <strong>opportunities</strong> and skill requirements.<br />

Many governments would like to establish<br />

extensive networks of <strong>rural</strong> training<br />

institutions, but do not have the necessary<br />

resources to do this. Most evaluations have<br />

found that the cost-effectiveness of <strong>youth</strong>related<br />

<strong>rural</strong> training is generally low<br />

(Middleton et al, 1993 and Bennell, 1999).<br />

Typically, training services are fragmented and<br />

there is no coherent policy framework to<br />

provide the basis of a pro-poor <strong>rural</strong> training<br />

system. There are some notable exceptions,<br />

mainly in South America – <strong>for</strong> example,<br />

18

BOX 4<br />

The San Francisco Agricultural School in Paraguay<br />

The San Francisco Agricultural School is run by the Fundacion Paraguaya. The school’s curriculum<br />

combines the teaching of traditional high-school subjects and technical skills with the running of<br />

17 small-scale <strong>rural</strong> enterprises, most of which are based on the school’s campus. All enterprises<br />

are strictly based on existing market demands and, <strong>for</strong> this reason, the income generated from<br />

them covers all the running costs of the school, including teacher salaries and depreciation. All of its<br />

students are productively engaged either in wage employment or self-employment within four<br />

months of graduation. Teacher accountability is very high because their own salaries are directly<br />

dependent on the immediate success of the school’s enterprises (ILO, 2008).<br />

the countrywide <strong>rural</strong> training and business<br />

support organization, SENAR, in Brazil.<br />

The key challenges in providing high-quality<br />

training and extension services <strong>for</strong> <strong>rural</strong> <strong>youth</strong><br />

are low educational levels, poor learning<br />

outcomes, scattered populations, low effective<br />

demand (from both the self-employed and<br />

employers) and limited scope <strong>for</strong> costrecovery.<br />

Church organizations and NGOs<br />

have supported much of the vocational<br />

training <strong>for</strong> <strong>rural</strong> school leavers in many<br />

developing countries, but funding constraints<br />

have resulted in significantly reduced<br />

enrolments in many countries during the last<br />

decade. The stigma attached to vocational and<br />

technical education is another major issue in<br />

most countries. Poor employment outcomes<br />

are a common weakness of <strong>rural</strong> training<br />

programmes. For example, about one-half<br />

of the young people who participated in the<br />

India-wide Training of Rural Youth <strong>for</strong><br />

Self-Employment have been unable to<br />

find employment. However, some training<br />

initiatives have been very successful. Farmer<br />

Field Schools in East Africa and the Fundacion<br />

Paraguaya are notable examples (see boxes 3<br />

and 4). In Uganda, the Programme <strong>for</strong> the<br />

Promotion of the Welfare of Children and<br />

Youth has provided good quality training,<br />

particularly in remote <strong>rural</strong> and war affected<br />

areas. Colombia and Nicaragua also have<br />

successful <strong>rural</strong> training programmes <strong>for</strong> <strong>youth</strong>.<br />

The capacity of service providers to support<br />

<strong>rural</strong> clienteles, especially <strong>rural</strong> <strong>youth</strong>, in all<br />

key sectors – such as education, health,<br />

policing, justice, <strong>rural</strong> infrastructure and<br />

agricultural extension – needs to be<br />

strengthened significantly in most<br />

countries, which has major implications <strong>for</strong><br />

higher education and training systems.<br />

Agricultural education at all levels also<br />

needs to be revitalized.<br />

19

Training and capacity-building activities<br />

now comprise an important component of<br />

<strong>IFAD</strong>-supported activities and absorb up to<br />

30 per cent of resources in some projects.<br />

Since key target groups are often illiterate or<br />

have little <strong>for</strong>mal schooling, this presents<br />

additional challenges <strong>for</strong> providing effective<br />

training. A good example of <strong>IFAD</strong> support<br />

in this area is the Skills Enhancement <strong>for</strong><br />

Employment Project in western Nepal,<br />

which targets Dalit and other seriously<br />

disadvantaged <strong>rural</strong> <strong>youth</strong>. The project has an<br />

ambitious goal of ensuring that 70 per cent<br />

of all trainees are in productive employment<br />

after six months. The project is implemented<br />

by ILO and is based on the ILO’s Training <strong>for</strong><br />

Economic Empowerment methodology,<br />

which is firmly rooted in participatory<br />

planning approaches and market-driven<br />

enterprise development. The Prosperer project<br />

in Madagascar is another good example of a<br />

new generation of <strong>youth</strong>-oriented projects<br />

being funded by <strong>IFAD</strong>. It seeks to improve the<br />

income of disadvantaged, poor <strong>youth</strong> in three<br />

regions of the country by providing<br />

diversified income-generating <strong>opportunities</strong><br />

and promoting entrepreneurship in <strong>rural</strong><br />

areas. A total of 8,000 young people will be<br />

supported over the next five years.<br />

Access to land and natural resources and land<br />

tenure security lie at the heart of all <strong>rural</strong><br />

societies and agricultural economies and are<br />

central to <strong>rural</strong> poverty eradication. Growing<br />

populations, declining soil fertility and<br />

increasing environmental degradation, the<br />

HIV/AIDS pandemic and new <strong>opportunities</strong><br />

<strong>for</strong> agricultural commercialisation, have all<br />

heightened demands and pressures on land<br />

resources and placed new pressures on land<br />

tenure systems, often at the expense of poor<br />

people and vulnerable groups such as women<br />

and <strong>youth</strong>. In many developing countries<br />

inheritance remains the main means <strong>for</strong><br />

young people to access land. Typically,<br />

though, it is sons who inherit land, and<br />

daughters only gain access to land through<br />

marriage. Ongoing subdivision of land<br />

through inheritance has resulted in<br />

fragmented and unviable land parcels and<br />

increasingly the <strong>youth</strong> are becoming landless.<br />

The HIV/AIDS pandemic has resulted in<br />

increasing land grabbing of widows’ and<br />

orphans’ lands by male relatives of the<br />

deceased, particularly in Africa. Increasing<br />

landlessness amongst the <strong>youth</strong> has resulted<br />

in an increase in inter-generational conflicts<br />

over land. Lasting solutions to land tenure<br />

insecurity of the <strong>youth</strong> could include:<br />

the strengthening of legislation and legal<br />

services to women and <strong>youth</strong> in order to<br />

recognize and defend their rights to land;<br />

the development of land markets as<br />

mechanisms <strong>for</strong> accessing land; and perhaps<br />

most importantly, the identification and<br />

promotion of off-farm economic activities<br />

that target the <strong>youth</strong>.<br />

Young people tend to view agriculture as<br />

an unsatisfactory option unless they have<br />

secure control over family lands. In the<br />

United Republic of Tanzania, as part of the<br />

national action plan <strong>for</strong> <strong>youth</strong> employment,<br />

labour intensive <strong>rural</strong> infrastructure<br />

development has been actively supported<br />

among <strong>youth</strong> groups in ‘green belts’ around<br />

major urban centres. The programme has also<br />

supported <strong>youth</strong> to own land by allocating<br />

areas <strong>for</strong> <strong>youth</strong> infrastructure development<br />

and enacting laws to protect <strong>youth</strong> from<br />

discrimination in leasing land.<br />

Financial capital – microfinance and<br />

enterprise development<br />

As the 2005 World Youth Report points out<br />

“entrepreneurship is not <strong>for</strong> everyone and so<br />

cannot be viewed as a large-scale solution to<br />

the <strong>youth</strong> employment crisis”. Nonetheless,<br />

there is growing interest in the targeted<br />

provision of micro-finance <strong>for</strong> <strong>youth</strong>, because<br />

it is recognized that, education and training<br />

do not on their own usually lead to<br />

sustainable self-employment. To date,<br />

however, services in this area remain limited.<br />

Numerous problems have been encountered<br />

in pilot projects. The lack of control of loans<br />

20

Women attend a literacy class in Qusiva village,<br />

Syrian Arab Republic<br />

©<strong>IFAD</strong>/J. Spaull<br />

BOX 5<br />

Employment creation <strong>for</strong> <strong>rural</strong> <strong>youth</strong> in NENA<br />

Sizeable enterprise development projects <strong>for</strong> young people are being funded by <strong>IFAD</strong> in Egypt and<br />

the Syrian Arab Republic. In Egypt, the focus is mainly on agro-processing and marketing activities<br />

in key high value and organic agricultural export sectors. Private banks will manage loans and close<br />

links will be established with agricultural exporters. The project is being implemented through<br />

community development organizations, which will take the lead in identifying <strong>youth</strong> participants. It is<br />

expected that 30,000 jobs will be created by the project during its eight-year lifetime. The project in<br />

the Syrian Arab Republic focuses on promoting <strong>youth</strong> enterprise in agricultural marketing activities in a<br />

poor area of the country.<br />

21

A young man makes and repairs<br />

shoes in Ruhengeri Town, Rwanda<br />

©<strong>IFAD</strong>/M. Millinga

y <strong>youth</strong> borrowers is a major issue, screening<br />

mechanisms are weak, and intensive training<br />

is needed in how to make best use of the<br />

money. Youth, and especially the very poor,<br />

are also frequently reluctant to borrow<br />

money. Integrated packages of inputs<br />

(credit, training, advisory support, other<br />

facilities) are often necessary, but this<br />

imposes major demands on organizations<br />

and significantly reduces the number of<br />

beneficiaries. Agricultural and enterprise<br />

development extension staff should be<br />

trained more to work with young people.<br />

The recent experience of the Population<br />

Council with microcredit schemes <strong>for</strong> <strong>youth</strong><br />

highlights the overriding importance of<br />

specific contextual factors in determining<br />

outcomes and impacts. In other words, what<br />

works in one place may fail completely in<br />

another (Amin, 2010). One of the largest<br />

<strong>youth</strong> credit schemes is currently being<br />

funded by <strong>IFAD</strong> in the Chongqing Province<br />

in China, where more than 100,000 returned<br />

migrant workers have been provided with<br />

microfinance and training in order to start<br />

a variety of agricultural and <strong>rural</strong> enterprises.<br />

<strong>IFAD</strong> provides substantial support <strong>for</strong> nonfarm<br />

enterprise development, but most<br />

projects in this area have not (at least until<br />

very recently) had any specific focus on <strong>rural</strong><br />

<strong>youth</strong>. Nonetheless, <strong>youth</strong> have benefited<br />

from these interventions. The success of<br />

what has become a national network of<br />

village banks in Benin is a good example.<br />

Similarly, as part of the <strong>IFAD</strong>-funded <strong>rural</strong><br />

enterprise project in Rwanda, 60 per cent of<br />

the 3,500 young people who completed sixmonth<br />

apprenticeships either started their<br />

own enterprises or continued to work as<br />

full-time employers in the enterprise where<br />

they were apprenticed. In Uganda, <strong>IFAD</strong><br />

(through the Belgian Survival Fund) provided<br />

US$3 million funding between 2000 and<br />

2004 to the development programme of<br />

the Uganda Women’s Ef<strong>for</strong>t to Save<br />

Orphans (UWESO). Loans were made to<br />

7,000 households with orphan members,<br />

with an overall loan recovery rate of<br />

95 per cent. In addition, 655 orphans were<br />

trained as artisans. However, as is invariably<br />

the case with project-elated training activities,<br />

insufficient data is available about the<br />

subsequent employment activities of these<br />

trainees to be able to reach firm conclusions<br />

about the cost-effectiveness of this training.<br />

Public employment generation<br />

Rural public works programmes are<br />

substitutes <strong>for</strong> unemployment benefit or<br />

income support systems in countries that<br />

cannot af<strong>for</strong>d such systems. If properly<br />

designed, they can per<strong>for</strong>m the role of a<br />

guaranteed employment scheme <strong>for</strong> the<br />

disadvantaged of all ages and they can be<br />

used to identify self-selecting groups of young<br />

workers who are most in need. However, a<br />

key conclusion of the World Bank Youth<br />

Inventory study is that “few public works<br />

programmes targeted on <strong>youth</strong> seem to lead to<br />

high employment chances <strong>for</strong> participants”<br />

(Betcherman et al, 2007).<br />

23

Partnerships to promote<br />

<strong>youth</strong> <strong>rural</strong> <strong>livelihood</strong>s<br />

A broad consensus exists that the rapid<br />

scaling up of <strong>rural</strong> <strong>youth</strong> development<br />

policies and programmes must be based<br />

on a multi sector approach with close<br />

coordination and partnerships between<br />

a wide array of public and private<br />

organizations. Youth networks and<br />

partnerships have to be established and<br />

effectively used at local, national and<br />

international levels.<br />

The presence and impact of international<br />

and national <strong>youth</strong> development<br />

organizations and initiatives continues to<br />

expand rapidly in all developing country<br />

regions. There are already a number of<br />

international global networks that focus<br />

on <strong>youth</strong> development. The FAO Rural Youth<br />

Development Programme is expected to play<br />

a major coordinating role, but lack of<br />

resources has prevented it from doing so in<br />

recent years. The Youth Employment Network<br />

(YEN), which was launched jointly by the<br />

United Nations, the World Bank and the<br />

ILO in 2001 to address the problem of<br />

unemployment among young people has<br />

been increasingly active. Currently, there are<br />

21 YEN Lead Countries, all of which have<br />

developed comprehensive national action<br />

plans <strong>for</strong> <strong>youth</strong> employment. The Network<br />

is also expected to regularly benchmark <strong>youth</strong><br />

policies and programmes. The Commonwealth<br />

Plan of Action <strong>for</strong> Youth Empowerment is<br />

another similar international initiative. An<br />

Inter-Agency Network on Youth Development<br />

has also been recently established by the UN.<br />

The International Youth Foundation, which is<br />

the most prominent international civil society<br />

organization in this area, seeks to mobilize<br />

the global community of businesses,<br />

governments and civil society organizations.<br />

To date, it has provided grants to nearly<br />

350 organizations in 86 countries. Major<br />

corporate sponsors include Merrill Lynch,<br />

Microsoft, Starbucks, Samsung and Nokia.<br />

Its highest profile initiatives are Entra 21,<br />

which equips disadvantaged <strong>youth</strong> in<br />

Latin America and the Caribbean with<br />

in<strong>for</strong>mation and communication technology<br />

and life skills, and its Global Partnership<br />

to Promote Youth Employment and<br />

Employability. However, most of its<br />

programmes are oriented mainly to <strong>for</strong>malsector<br />

employment in urban areas. Poorer<br />

countries also tend to be under-represented<br />

in its activities.<br />

Establishing effective national <strong>youth</strong><br />

development strategies is a major challenge.<br />

As the 2007 World Development Report<br />

notes, “influencing <strong>youth</strong> transitions requires<br />

working across many sectors, yet few<br />

24

countries take a coherent approach to<br />

establish clear lines of responsibility and<br />

accountability <strong>for</strong> <strong>youth</strong> outcomes.”<br />

There is a need <strong>for</strong> long-term coordinated<br />

interventions, which are part and parcel of<br />

a much broader national integrated strategy<br />

<strong>for</strong> <strong>rural</strong> development, growth and job creation.<br />

At both the national or subnational level,<br />

where <strong>rural</strong> <strong>youth</strong> can be identified as a highpriority<br />

social category with distinct<br />

development and <strong>livelihood</strong> improvement<br />

needs, <strong>IFAD</strong> should concentrate on<br />

developing strategic partnerships with other<br />

organizations that focus on improving the<br />

<strong>livelihood</strong>s of <strong>youth</strong>, and <strong>rural</strong> <strong>youth</strong> in<br />

particular. This is especially important in<br />

<strong>IFAD</strong>’s own core areas of mandated activity,<br />

namely increasing agricultural and non<br />

agricultural productivity and employment<br />

and income generation. However, <strong>IFAD</strong><br />

should also contribute to policy <strong>for</strong>mulation<br />

and implementation in other key areas,<br />

such as curriculum development <strong>for</strong><br />

agriculture courses.<br />

A worker grinds cassava in a<br />

local business in Wenchi,<br />

Ghana<br />

©<strong>IFAD</strong>/P. Maitre

Concluding remarks<br />

The urgent need to intensify development<br />

ef<strong>for</strong>ts on <strong>rural</strong> <strong>youth</strong> is increasingly<br />

recognized by governments, civil society<br />

organizations and international development<br />

agencies. This is reflected in a variety of<br />

exciting new initiatives that seek to improve<br />

the <strong>livelihood</strong>s of disadvantaged <strong>rural</strong> <strong>youth</strong>.<br />

The overriding challenge is to unleash the<br />

energy and creativity of young people living<br />

in <strong>rural</strong> areas, especially those who are the<br />

most marginal and vulnerable. Rural <strong>youth</strong>,<br />

and especially young women, need to be<br />

empowered to become agents of innovation<br />

and social actors capable of developing new,<br />

viable models of <strong>rural</strong> development.<br />

<strong>IFAD</strong> is increasing its support <strong>for</strong> <strong>rural</strong> <strong>youth</strong><br />

programming. As part of this ef<strong>for</strong>t, <strong>IFAD</strong> is<br />

collaborating with the ILO to review<br />

strategies and programmes <strong>for</strong> promoting<br />

productive employment among <strong>rural</strong> <strong>youth</strong><br />

in developing countries. Given the enormous<br />

challenges these young people face,<br />

this support should be intensified in the future<br />

with <strong>rural</strong> <strong>youth</strong> mainstreamed in all <strong>IFAD</strong><br />

policies and programmes.<br />

The development of coherent, comprehensive<br />

national policies on <strong>rural</strong> <strong>youth</strong> should<br />

become a top priority <strong>for</strong> all governments,<br />

but this must be backed up with more<br />

research. The prominence of national action<br />

plans <strong>for</strong> <strong>youth</strong> employment should also be<br />

increased, and it is essential that they are fully<br />

embedded in other key national planning<br />

documents, especially PRSPs. This should be<br />

closely linked with increased ef<strong>for</strong>ts to promote<br />

<strong>youth</strong> participation in all areas of policymaking.<br />

Finally, the knowledge base of what works<br />

needs to be strengthened rapidly, especially<br />

with regard to innovative, strongly pro-poor<br />

<strong>rural</strong> <strong>youth</strong> development programmes and<br />

projects that have been successfully scaled-up.<br />

26

A young woman sells vegetables at a market<br />

in La Trinidad, Philippines.<br />

©<strong>IFAD</strong>/GMB Akash