Save PDF (1.9 MB) - CORE

Save PDF (1.9 MB) - CORE

Save PDF (1.9 MB) - CORE

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

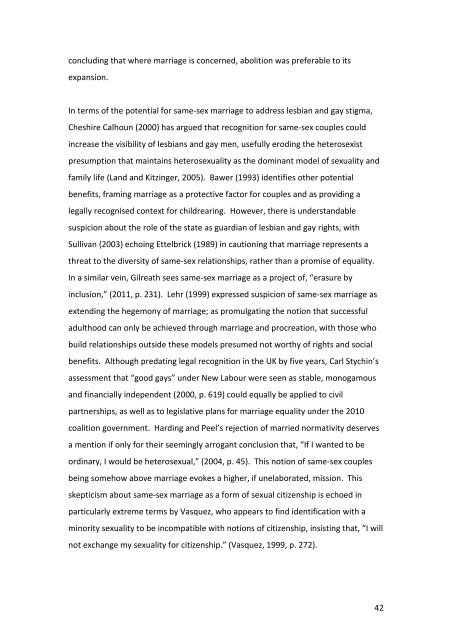

concluding that where marriage is concerned, abolition was preferable to its<br />

expansion.<br />

In terms of the potential for same-sex marriage to address lesbian and gay stigma,<br />

Cheshire Calhoun (2000) has argued that recognition for same-sex couples could<br />

increase the visibility of lesbians and gay men, usefully eroding the heterosexist<br />

presumption that maintains heterosexuality as the dominant model of sexuality and<br />

family life (Land and Kitzinger, 2005). Bawer (1993) identifies other potential<br />

benefits, framing marriage as a protective factor for couples and as providing a<br />

legally recognised context for childrearing. However, there is understandable<br />

suspicion about the role of the state as guardian of lesbian and gay rights, with<br />

Sullivan (2003) echoing Ettelbrick (1989) in cautioning that marriage represents a<br />

threat to the diversity of same-sex relationships, rather than a promise of equality.<br />

In a similar vein, Gilreath sees same-sex marriage as a project of, “erasure by<br />

inclusion,” (2011, p. 231). Lehr (1999) expressed suspicion of same-sex marriage as<br />

extending the hegemony of marriage; as promulgating the notion that successful<br />

adulthood can only be achieved through marriage and procreation, with those who<br />

build relationships outside these models presumed not worthy of rights and social<br />

benefits. Although predating legal recognition in the UK by five years, Carl Stychin’s<br />

assessment that “good gays” under New Labour were seen as stable, monogamous<br />

and financially independent (2000, p. 619) could equally be applied to civil<br />

partnerships, as well as to legislative plans for marriage equality under the 2010<br />

coalition government. Harding and Peel’s rejection of married normativity deserves<br />

a mention if only for their seemingly arrogant conclusion that, “If I wanted to be<br />

ordinary, I would be heterosexual,” (2004, p. 45). This notion of same-sex couples<br />

being somehow above marriage evokes a higher, if unelaborated, mission. This<br />

skepticism about same-sex marriage as a form of sexual citizenship is echoed in<br />

particularly extreme terms by Vasquez, who appears to find identification with a<br />

minority sexuality to be incompatible with notions of citizenship, insisting that, “I will<br />

not exchange my sexuality for citizenship.” (Vasquez, 1999, p. 272).<br />

42