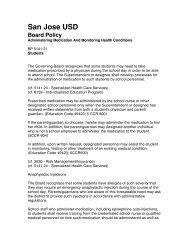

Introduction to Immigration

Introduction to Immigration

Introduction to Immigration

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Introduction</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Immigration</strong><br />

Wide open and unguarded stand our gates,<br />

And through them presses a wild, motley throng..<br />

Flying the Old World's poverty and scorn;<br />

These bringing with them unknown gods and rites.<br />

Those, tiger passions, here <strong>to</strong> stretch their claws.<br />

So wrote poet Thomas Bailey Aldrich in an 1892 issue of the Atlantic Monthly. The Statue of Liberty<br />

had been unveiled just six years earlier, though Emma Lazarus's lines of poetry, "Give me your tired,<br />

your poor ..." would not be inscribed on the pedestal until 1903.Aldrich's poem represented a rising<br />

feeling in America. Too many immigrants were arriving. The "American way of life" was threatened.<br />

What had happened in the country where everyone, except the native American Indian and the black<br />

slave, was either an immigrant or descended from one?<br />

Before 1980 the vast majority of immigrants had come from northwestern Europe—England,<br />

Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Holland, Norway, Sweden, and<br />

Switzerland. After the Civil War, however, immigration from northwest Europe begun <strong>to</strong> slow down-<br />

And as Americans became educated, they had less desire <strong>to</strong> perform the underpaid, unskilled jobs that<br />

still needed doing. So immigrants from untapped sources —the countries of southern and eastern<br />

Europe— were now sought. Agents from states and private companies fanned out <strong>to</strong> Italy, Greece, the<br />

Austro-Hungarian Umpire, Bulgaria, Montenegro, Poland, Rumania, Russia, Serbia, and the Ot<strong>to</strong>man<br />

Empire looking for workers.<br />

And the immigrants came. In 1854 a <strong>to</strong>tal of 427,833 arrived; in 1882, 788,992 entered the<br />

country. And then came the deluge. The peak year was 1907 when 1,285,349 persons arrived. From<br />

1905 until the start of the First World War in 1914 the million mark was exceeded six times. More<br />

immigrants came from 1860 <strong>to</strong> 1930 than the entire United States population in 1860.<br />

To process such huge numbers the Ellis Island Immigrant Station was opened on January I,<br />

1892, less than half a mile from the Statue of Liberty in New York Harbor. In the next fifty years some<br />

sixteen million immigrants passed through Ellis Island, nearly seventy percent of all those who entered<br />

the country. A National Park Service officer said:<br />

To almost everyone who passed through it, and their descendants as well,<br />

Ellis Island has been as important in fact as Plymouth Rock has<br />

now become in fancy for the descendants of those who came in the first<br />

colonization wave-'<br />

All steerage passengers on incoming ships had lo go <strong>to</strong> Ellis Island. Before disembarking, all<br />

passengers, no matter what class, were inspected on board ship for contagious diseases and for live<br />

epidemic diseases: cholera, plague, smallpox, typhus, and yellow fever. Those with suspicious<br />

symp<strong>to</strong>ms were taken <strong>to</strong> Ellis Island. --

The arrivals were nervous about their upcoming inspection. In 191 I an observer wrote:<br />

“The immigrants are in a constant turmoil of excitement until they board the ferryboats on the last lap<br />

of their journeys. To them Ellis Island is a complicated labyrinth leading <strong>to</strong> freedom. . - - They obey<br />

the signs, gestures and directions of the attendants as dumbly as cattle, and as patiently.'”<br />

At the height of the immigration tide, signs at Ellis Island were written in nine languages:<br />

English, German, Greek, Yiddish, Italian, Hungarian, Polish, Russian, and a Scandinavian (usually<br />

Swedish) language. Interpreters s<strong>to</strong>od by <strong>to</strong> ease the processing. Before he was elected mayor of New<br />

York City. Friorello La Ciuardia, who knew Italian, German, Yiddish, French, Hungarian, and<br />

Croatian, and who himself was the son of Italian immigrants, worked as an interpreter at Ellis Island<br />

from 1908 <strong>to</strong> 1910. He recalled:<br />

I never managed during the years I worked there <strong>to</strong> become callous <strong>to</strong> the mental anguish, the<br />

disappointment and the despair I witnessed almost daily. ... At best the work was an ordeal."<br />

La Guardia and the other interpreters questioned the immigrants as <strong>to</strong> their destinations and<br />

political views near the end of the standard inspection. First they were herded in<strong>to</strong> a mazelike registry<br />

room where they awaited their medical exams. The doc<strong>to</strong>rs checked for visible physical defects: lameness,<br />

blindness, deafness, and the most obvious mental defects. Next came the check for contagious<br />

diseases: ringworm, leprosy, venereal diseases, and tuberculosis. Doc<strong>to</strong>rs marked with chalk "T.D.,"<br />

for temporarily detained, on those having suspicious symp<strong>to</strong>ms. Anastasia Stephanies recalls being<br />

held at Ellis Island after arriving from Greece because her sister had trachoma, a contagious eye<br />

disease:<br />

I came in 1922. All my family came here: my mother, my sisters, and my brothers. When we came <strong>to</strong><br />

America, we came <strong>to</strong> Ellis Island and stayed there two weeks. My brother was in the army. He came <strong>to</strong><br />

pick us up but couldn't. They said, "You have <strong>to</strong> stay on Ellis Island two weeks." My youngest sister<br />

had something in her eyes. I didn't know what was going <strong>to</strong><br />

happen. But the thy we could all leave the doc<strong>to</strong>r said, "your sister can’t go out because<br />

we have <strong>to</strong> take her <strong>to</strong> the hospital." My brother picked us up, but my youngest sister was taken <strong>to</strong> the<br />

hospital. She lived forty days, but after forty days, my sister died.”<br />

Fifteen percent of the immigrants at Ellis Island were marked with chalk for further examination.<br />

In addition <strong>to</strong> "T.D.," another major category was "S.I.," special inquiry; usually this was for a suspected<br />

criminal or political troublemaker. "L.P.C.," meant likely <strong>to</strong> become a public charge. Although<br />

confusing and anxiety-provoking for immigrants, the system was remarkably efficient. At peak limes<br />

as many as five thousand people per day were processed through Ellis Island.<br />

Officials at Ellis Island were following laws passed by the federal government. Until 1975 there<br />

were no restrictions on the admission of immigrants. Until in 1875 Congress responded <strong>to</strong> the marked<br />

anti alien feeling in America and excluded criminals and prostitutes. As the result of subsequent acts

through 1907, "lunatics." "idiots," "imbeciles," "persons suffering from loathsome and contagious<br />

diseases," dependent people, and "subversives" were excluded, as well as those hired as cheap labor by<br />

contract from abroad.<br />

Those early laws did not discriminate against any particular nationality, but differences between<br />

the "new" immigrants (those arriving after 1880) and the "old" immigrants had spurred a new look<br />

at the laws. By 1910 nearly fifteen percent of the population was foreign-born—not a big increase over<br />

the thirteen percent figure for 1860. But their actual numbers were far greater. And their faces,<br />

accents, and jobs had changed. From 1821 <strong>to</strong> 1880 only some two percent of all immigrants came<br />

from southern and eastern Europe. From 1901 <strong>to</strong> 1911 more than seventy percent came from that area<br />

which most Americans knew little about. These "new" immigrants tended <strong>to</strong> live <strong>to</strong>gether in big-city<br />

ghet<strong>to</strong>s. Would they ever become "real Americans"?<br />

That question was put early and often by many respected members of the national community.<br />

Because the Italians were by far the largest nationality among the newer immigrants, the question frequently<br />

concerned them. An article in the Popular Science Monthly of December 1890 was titled<br />

"What Shall We Do with the Dago?" and charged that Italians loved <strong>to</strong> use their knives "<strong>to</strong> lop off<br />

another dago’s finger or ear, or <strong>to</strong> slash another’s cheek." A New York City newspaper in the 1890s<br />

wrote:<br />

The floodgates are open. The bars are down. The sally-ports are unguarded. The dam is washed<br />

away. The sewer is choked. Europe is vomiting! In other words, the scum of immigration is<br />

viscerating upon our shores. The horde of $9.60 steerage slime is being siphoned upon us from<br />

Continental mud tanks."<br />

Prominent New Englanders founded the first <strong>Immigration</strong> Restriction League in Bos<strong>to</strong>n in 1894.<br />

Others sprung up around the country. Labor leaders, who at first had welcomed the new workers,<br />

changed their minds. Samuel Gompers, president of the American Federation of Labor and who<br />

himself had emigrated from England, argued that…<br />

"both the intelligence and the prosperity of our working people are endangered by the present<br />

immigration. Cheap labor, ignorant labor, takes our jobs and cuts our wages."<br />

John Mitchell, president of the United Mine Workers put it even more forcefully:<br />

No matter how decent and self-respecting and hard working the aliens who are flooding this country<br />

may be, they are invading the land of Americans, and whether they know it or not are helping <strong>to</strong> take<br />

the bread out of their mouths. America for Americans should be the mot<strong>to</strong> of every citizen, whether he<br />

be a working man or a capitalist. ., . There is not enough work for the many millions of unskilled<br />

laborers, and there is no need for the added millions who are pressing in<strong>to</strong> our cities and <strong>to</strong>wns <strong>to</strong><br />

compete with the skilled American in his various trades and occupations. While the majority of the<br />

immigrants are not skilled workmen, they rapidly become so, and their competition is not of a<br />

stimulating order.”

The national clamor almost forced politicians <strong>to</strong> lake a position on the immigration issue. Some,<br />

like Sena<strong>to</strong>r Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts, joined the anti-Italian crusade with enthusiasm:<br />

“This great Republic should no longer be left unguarded from them," he said." President Theodore<br />

Roosevelt hoped <strong>to</strong> cool the controversy by establishing a commission <strong>to</strong> study the problem. Known as<br />

the Dillingham Commission, after its chairman Sena<strong>to</strong>r William Paul Dillingham of Vermont, the<br />

panel studied the issue for three years and came out with a forty-two-volume report. Its conclusions<br />

were heavily weighted against the new immigrants. Serbo-Croatians had "savage manners"; Poles<br />

were "high-strung"; Italians had "not attained distinguished success as farmers."<br />

A major goal of restrictionists during this period was a literacy requirement. Congress first<br />

passed such a law in 1896, but President Grover Cleveland ve<strong>to</strong>ed it. Congress passed it again in 1913<br />

and 1915 but it was again ve<strong>to</strong>ed, first by William Howard Taft and then by Woodrow Wilson. Said<br />

Wilson: "Those who come seeking an opportunity are not <strong>to</strong> be admitted unless they have already had<br />

one of the chief . . . opportunities they seek, the opportunity of education." Nonetheless, Congress<br />

passed it two years later in 1917 over his ve<strong>to</strong>.<br />

World War 1 brought a natural slowdown of immigration. In fact, Ellis Island was used during<br />

the war <strong>to</strong> hold prisoners of war and suspected aliens and spies. Following the war, however, immigration<br />

showed signs of reaching new heights. From June 1920 <strong>to</strong> June 1921, 805,000 arrived, and<br />

more than sixty-five percent of them were from southern and eastern Europe. Ellis Island was so<br />

jammed that some ships had <strong>to</strong> be diverted <strong>to</strong> Bos<strong>to</strong>n.<br />

Anti foreign sentiment in the country had been raised <strong>to</strong> a near frenzy by the war, and now more<br />

immigrants were heading for America. Congress, responding <strong>to</strong> pressure, passed its first Quota Act in<br />

1921. It limited new aliens <strong>to</strong> three percent of each nationality present in the country according <strong>to</strong> the<br />

1910 census. The 1924 Quota Act went even further, limiting new aliens <strong>to</strong> two percent of those<br />

nationalities present according <strong>to</strong> the 1890 census —before the new immigrants had arrived in such<br />

large numbers.<br />

The law was designed <strong>to</strong> limit <strong>to</strong>tal immigration, but it’s major goal was <strong>to</strong> keep out the newer<br />

immigrants, The quota from Italy became around 5,000 per year; in 1907, 285,000 Italians had come<br />

<strong>to</strong> America.<br />

Before America moved <strong>to</strong> close its doors, millions of immigrants had arrived from southern<br />

Europe. They would change the composition of the country for good: more than 5 million Italians,<br />

600,000 Greeks 300,000 Portuguese, and 200,000 Spaniards.