Outsiders and Outcasts in the Mexica World - Numilog

Outsiders and Outcasts in the Mexica World - Numilog

Outsiders and Outcasts in the Mexica World - Numilog

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Introduction<br />

The <strong>Mexica</strong> 1 made up one of <strong>the</strong> most significant groups of people <strong>in</strong> ancient<br />

Mexico. The consolidation <strong>and</strong> expansion of this group dates to <strong>the</strong><br />

Late Postclassic (A.D. 1200–1521), <strong>the</strong> period preced<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> conquest of Tenochtitlan.<br />

The <strong>Mexica</strong> arrived <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> bas<strong>in</strong> of Mexico after o<strong>the</strong>r Nahua tribes had<br />

already occupied <strong>the</strong> best l<strong>and</strong>s. They settled temporarily <strong>in</strong> various places<br />

until, free of all subjugation, <strong>the</strong>y established <strong>the</strong>ir def<strong>in</strong>itive settlement on<br />

a small islet that Huitzilopochtli, <strong>the</strong>ir tutelary god, had designated for <strong>the</strong>m.<br />

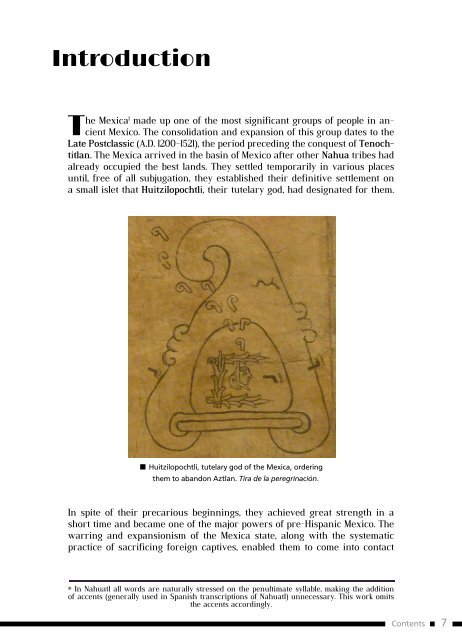

Huitzilopochtli, tutelary god of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Mexica</strong>, order<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>the</strong>m to ab<strong>and</strong>on Aztlan. Tira de la peregr<strong>in</strong>ación.<br />

In spite of <strong>the</strong>ir precarious beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>gs, <strong>the</strong>y achieved great strength <strong>in</strong> a<br />

short time <strong>and</strong> became one of <strong>the</strong> major powers of pre-Hispanic Mexico. The<br />

warr<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> expansionism of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Mexica</strong> state, along with <strong>the</strong> systematic<br />

practice of sacrific<strong>in</strong>g foreign captives, enabled <strong>the</strong>m to come <strong>in</strong>to contact<br />

* In Nahuatl all words are naturally stressed on <strong>the</strong> penultimate syllable, mak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> addition<br />

of accents (generally used <strong>in</strong> Span ish transcriptions of Nahuatl) unnecessary. This work omits<br />

<strong>the</strong> accents accord<strong>in</strong>gly.<br />

Contents 7

with a great variety of people hav<strong>in</strong>g different languages <strong>and</strong> customs, on<br />

whom <strong>the</strong>y imposed tribute. War <strong>and</strong> tributary subjection were among <strong>the</strong><br />

catalysts for <strong>in</strong>terethnic relations among Nahua groups 2 —those who lived <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> bas<strong>in</strong>—<strong>and</strong> foreign-speak<strong>in</strong>g people.<br />

Expansion of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Mexica</strong> Empire (based on López Aust<strong>in</strong> <strong>and</strong> López Luján).<br />

MEXICO<br />

Tuxpan<br />

MEXICO<br />

METZTITLÁN<br />

Texcoco<br />

Tlacopan<br />

Tz<strong>in</strong>tzuntzán<br />

MICHOACÁN<br />

Tenochtitlan<br />

TLAXCALA<br />

Tlaxcala<br />

TEOTITLÁN<br />

DEL CAMINO<br />

Gulf of Mexico<br />

YOPITZINCO<br />

MIXTEC<br />

LORDLY<br />

DOMAINS<br />

COATLICÁMAC<br />

Oaxaca<br />

Pacific Ocean<br />

TUTUTEPEC<br />

SOCONUSCO<br />

<strong>Mexica</strong> Empire<br />

Triple Alliance<br />

Independent political units<br />

Road to Soconusco<br />

But <strong>the</strong>se peripheral cultures presented a great many customs that were not<br />

<strong>in</strong> keep<strong>in</strong>g with <strong>Mexica</strong> practices: those concern<strong>in</strong>g food, bodily treatment,<br />

styles of dress <strong>and</strong> adornment, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> characteristics of sacrifices, among<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r features. The fact that foreigners spoke a language o<strong>the</strong>r than Nahuatl<br />

was one of <strong>the</strong> essential criteria that formed <strong>the</strong>ir alterity. We need only read<br />

Introduction<br />

Contents<br />

8

ook 10, chapter 29, of <strong>the</strong> Florent<strong>in</strong>e Codex—compiled by <strong>the</strong> Franciscan friar<br />

Bernard<strong>in</strong>o de Sahagún <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> second half of <strong>the</strong> sixteenth century, with <strong>the</strong><br />

collaboration of Nahua <strong>in</strong>formants—to see what <strong>the</strong> <strong>Mexica</strong>, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Nahuas<br />

<strong>in</strong> general, thought of <strong>the</strong>ir foreign neighbors, both near <strong>and</strong> far. This text<br />

exposes <strong>the</strong>ir Nahuacentric view of different ethnic groups, for it does not<br />

stop at describ<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> physical characteristics <strong>and</strong> cultural ways of <strong>the</strong>se<br />

people but also criticizes <strong>the</strong>m, measur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>m aga<strong>in</strong>st <strong>the</strong> <strong>Mexica</strong>’s own<br />

ideals. This can be seen very clearly <strong>and</strong> schematically <strong>in</strong> references to <strong>the</strong><br />

Otomi <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Cuextecs. 3 While po<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g out <strong>the</strong>ir supposed faults, <strong>in</strong>stead of<br />

giv<strong>in</strong>g an objective description of those aspects, <strong>the</strong> text exalts <strong>the</strong> <strong>Mexica</strong><br />

moral system. Everyth<strong>in</strong>g that does not agree with that system becomes a<br />

transgression. Thus, <strong>the</strong> foreigner was made out to be an immoral be<strong>in</strong>g,<br />

moreover characterized by dullness <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>eptitude. 4 At <strong>the</strong> same time, <strong>the</strong><br />

way <strong>in</strong> which <strong>the</strong> <strong>Mexica</strong> spoke of non-Nahua foreigners reflected <strong>the</strong> wars<br />

<strong>the</strong>y waged aga<strong>in</strong>st <strong>the</strong>m, s<strong>in</strong>ce all were considered enemies of <strong>the</strong> Empire<br />

for cont<strong>in</strong>ually counter<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>ir military attacks <strong>and</strong> resist<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>ir tribute.<br />

Foreigners were <strong>in</strong>corporated not only <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> moral system but also <strong>in</strong> rituals,<br />

myths, <strong>and</strong> war; <strong>the</strong>y played important religious <strong>and</strong> social roles.<br />

Human sacrifice through heart extraction.<br />

Florent<strong>in</strong>e Codex.<br />

Introduction<br />

Contents 9

The Otomi were portrayed with long hair <strong>and</strong> cloaks made of wild animal sk<strong>in</strong>s.<br />

Florent<strong>in</strong>e Codex.<br />

But <strong>the</strong> <strong>Mexica</strong> also recognized <strong>and</strong> repudiated those <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir own community<br />

who did not completely satisfy <strong>the</strong>ir social <strong>and</strong> moral requirements, such as<br />

youths who failed to respect parental orders, or heavy dr<strong>in</strong>kers, vagabonds,<br />

lunatics, <strong>and</strong> women of loose or “happy” ways.<br />

Foreigners <strong>and</strong> socially marg<strong>in</strong>alized figures shared many traits of immorality;<br />

<strong>in</strong>deed, <strong>the</strong>ir identities could be merged <strong>in</strong>to one: <strong>the</strong> Cuextec man<br />

resembled <strong>the</strong> drunkard <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> lunatic; <strong>the</strong> Otomi woman <strong>and</strong> man, <strong>the</strong><br />

prostitute <strong>and</strong> vagabond, respectively. They constituted <strong>the</strong> <strong>Mexica</strong> counterideal,<br />

a common element <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> general process of self-def<strong>in</strong>ition through<br />

negative identification—that is, through what one is not.<br />

Introduction<br />

Prostitute hold<strong>in</strong>g flowers <strong>and</strong> shown with<br />

sea motifs. Florent<strong>in</strong>e Codex.<br />

Contents 10

<strong>Mexica</strong> Moral<br />

<strong>and</strong> Behavioral Systems<br />

<strong>Mexica</strong> moral ideals can be summed up by <strong>the</strong> adage tlacoqualli <strong>in</strong><br />

monequi, “<strong>the</strong> good medium is necessary,” 5 exhort<strong>in</strong>g moderation<br />

<strong>in</strong> one’s dress, bear<strong>in</strong>g, speech, eat<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>and</strong> sexual behavior. This pr<strong>in</strong>ciple was<br />

expressed through a series of admonitory speeches called hue huetlatolli, or<br />

“ancient word.” Such speeches were an everyday part of family life, among<br />

not only nobles but also artisans <strong>and</strong> macehuales. They <strong>in</strong>cluded courtesy<br />

formulas along with advice, exhortations, <strong>and</strong> warn<strong>in</strong>gs that parents would<br />

give to <strong>the</strong>ir children. 6<br />

There were surely differences among<br />

<strong>the</strong> huehuetlatolli for different classes,<br />

<strong>and</strong> not merely <strong>in</strong> terms of rhetoric.<br />

For example, although moderation was<br />

urged at every social level, <strong>the</strong> rul<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>Mexica</strong> goddess <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> typical female<br />

posture: rest<strong>in</strong>g on her knees.<br />

FCAS collection. INAH 1041-210.<br />

<strong>Mexica</strong> man <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> typical male<br />

posture: st<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Museo Nacional de Antropología.<br />

Contents 11

A ruler exhorts his people. Florent<strong>in</strong>e Codex.<br />

class enforced <strong>the</strong> most str<strong>in</strong>gent limits on<br />

behavior <strong>in</strong> order to justify <strong>the</strong>ir superior<br />

status before <strong>the</strong> macehual masses. In<br />

this way <strong>the</strong> noble dist<strong>in</strong>guished himself<br />

from <strong>the</strong> peasant, while, on ano<strong>the</strong>r level,<br />

this behavioral code dist<strong>in</strong>guished <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Mexica</strong> ethnic group from all o<strong>the</strong>rs <strong>and</strong><br />

positioned <strong>the</strong> foreigner at <strong>the</strong> opposite<br />

extreme <strong>in</strong> terms of correct behavior.<br />

A fa<strong>the</strong>r exhorts his son to good<br />

behavior. Florent<strong>in</strong>e Codex.<br />

The Proper Way to Walk<br />

A fa<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong>structs his son:<br />

You must be prudent <strong>in</strong> your travels;<br />

peacefully, calmly, tranquilly […] are you<br />

to go, to take to <strong>the</strong> road, to travel. Do not<br />

throw your feet much, nor raise <strong>the</strong>m<br />

high, nor go jump<strong>in</strong>g, lest you be called<br />

foolish, shameless. Nor are you to go very<br />

slowly, or drag your feet. 7 […] nei<strong>the</strong>r too<br />

hurriedly nor too leisurely, but with honesty<br />

<strong>and</strong> maturity [are you to go]. 8<br />

O<strong>the</strong>rwise, as Sahagún <strong>in</strong>dicates, one<br />

would be called ixtotomac cuecuetz.<br />

The young noblewoman was told to walk<br />

without haste, that is, without restlessness<br />

(cuecuetzyotl), 9 <strong>and</strong> without w<strong>and</strong>er<strong>in</strong>g,<br />

so as not to seem ostentatious;<br />

she was to keep her head lowered as<br />

she walked, show<strong>in</strong>g no pride; <strong>and</strong> she<br />

was not supposed to look up or from<br />

side to side, s<strong>in</strong>ce that would <strong>in</strong>dicate<br />

<strong>Mexica</strong> Moral <strong>and</strong> Behavioral Systems<br />

Contents 12

hypocrisy. Nor should she behave<br />

sheepishly or cover her mouth, <strong>and</strong><br />

by no means could she look someone<br />

directly <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> eye. 10 She was to walk<br />

nei<strong>the</strong>r hurriedly nor slowly, nei<strong>the</strong>r<br />

lift<strong>in</strong>g her feet high nor dragg<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>m;<br />

mov<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> a straight l<strong>in</strong>e, with no sway<strong>in</strong>g<br />

motion.<br />

Noblewoman. Florent<strong>in</strong>e Codex.<br />

Cloth<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> Personal Groom<strong>in</strong>g<br />

The type of cloth<strong>in</strong>g a person wore constituted<br />

a language that communicated<br />

his or her status: social class, ethnicity,<br />

<strong>and</strong> age; it also <strong>in</strong>dicated how to<br />

act <strong>and</strong> what attitude to take toward a<br />

particular <strong>in</strong>dividual. It is possible that<br />

<strong>the</strong> Nahuas related certa<strong>in</strong> attire <strong>and</strong><br />

adornments with specific behaviors,<br />

s<strong>in</strong>ce moderation <strong>in</strong> dress prevailed<br />

over excess <strong>and</strong> ostentation. Nei<strong>the</strong>r<br />

men nor woman were to wear gaudy<br />

clo<strong>the</strong>s (topallotl), garments covered<br />

<strong>in</strong> adornment, because do<strong>in</strong>g so would<br />

imply vanity, “little sense <strong>and</strong> folly”;<br />

but nor were <strong>the</strong>y to dress <strong>in</strong> tatters<br />

(tzotzomatli), “a sign of poverty <strong>and</strong><br />

baseness” for nobles <strong>and</strong> of ridicule for<br />

<strong>the</strong> rest of society. 11<br />

There were quite precise <strong>in</strong>structions<br />

on how to wear a cape or cloak correctly.<br />

A young pilli was forbidden to<br />

let it drag on <strong>the</strong> ground or to wear it<br />

hang<strong>in</strong>g so far down that he would trip<br />

on it while walk<strong>in</strong>g. Nor was he to knot<br />

it so short that it would sit very high, or<br />

<strong>Mexica</strong> Moral <strong>and</strong> Behavioral Systems<br />

Contents 13

Noblewomen display<strong>in</strong>g different hairstyles, based on <strong>the</strong>ir social status. Florent<strong>in</strong>e Codex.<br />

<strong>Mexica</strong> Moral <strong>and</strong> Behavioral Systems<br />

Contents 14

to tie it at <strong>the</strong> armpits. Instead, it was to<br />

be tied <strong>in</strong> such a way that <strong>the</strong> shoulders<br />

would be kept covered. 12<br />

Young men were also persuaded to<br />

shun adornment:<br />

Do not comb your hair constantly; don’t<br />

keep look<strong>in</strong>g at yourself <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> mirror;<br />

don’t cont<strong>in</strong>ually adorn yourself; don’t<br />

groom yourself all <strong>the</strong> time; do not frequently<br />

desire ornament, because it is<br />

noth<strong>in</strong>g more than <strong>the</strong> devil’s way to trap<br />

people. 13<br />

An old man with his cape knotted at armpit level. Codex Mendoza.<br />

<strong>Mexica</strong> Moral <strong>and</strong> Behavioral Systems<br />

Contents 15