III. Painting Technique and Restoration (PDF, 5,21 MB) - Koninklijk ...

III. Painting Technique and Restoration (PDF, 5,21 MB) - Koninklijk ...

III. Painting Technique and Restoration (PDF, 5,21 MB) - Koninklijk ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

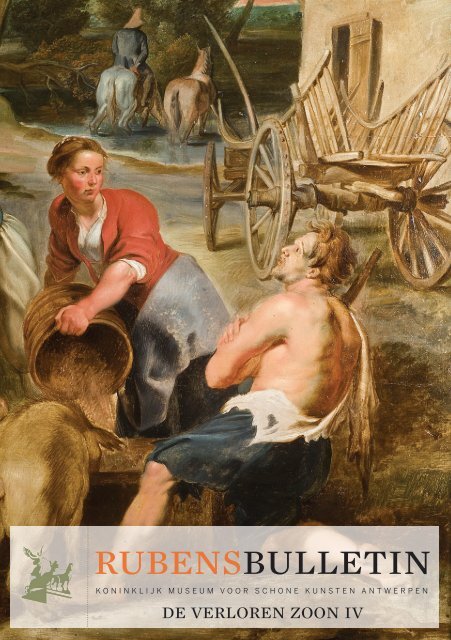

BULLETIN<br />

rubensbulletin<br />

KONINKLIJK MUSEUM VOOR SCHONE KUNSTEN ANTWERPEN<br />

de verloren zoon iv

BULLETIN<br />

BULLETIN<br />

THE PRODIGAL SON<br />

BY PETER PAUL RUBENS<br />

<strong>III</strong>. PAINTING TECHNIQUE AND RESTORATION<br />

Susan Farnell<br />

with additional comments by Nico Van Hout<br />

The recent restoration<br />

The Prodigal Son has just been restored. It was in good condition but the<br />

restoration was necessary because it was becoming increasingly difficult<br />

to see the painting through the layers of thick <strong>and</strong> discoloured varnish.<br />

Rubens must have intended the dramatic perspective of the view through<br />

the barn to give an added sense of depth to this composition while also<br />

experimenting with the effects of daylight <strong>and</strong> c<strong>and</strong>lelight. The loss of<br />

transparency <strong>and</strong> the browning of the varnish had not only dulled the<br />

colours but had also greatly reduced the sense of space <strong>and</strong> light within<br />

the painting. The restoration has involved the gradual removal of the layers<br />

of varnish <strong>and</strong> over-painting from what is often a remarkably thin paint<br />

layer. There has been wide use made of brown glazes in this painting. In<br />

many areas the paint is applied so thinly that the underlying light ground<br />

can be seen through the brush-strokes. Fortunately the general condition<br />

of the paint layer was good with few important losses. The restoration has<br />

meant that we can now see Rubens’ painting clearly; we can appreciate<br />

the different sources of light, the free h<strong>and</strong>ling of the paint <strong>and</strong> the<br />

extraordinary sense of depth within the composition.<br />

Technical study<br />

The restoration process provides an ideal occasion to observe a painting at<br />

close quarters <strong>and</strong> at the same time the opportunity to carry out technical<br />

<strong>and</strong> scientific documentation. 1<br />

The advantage of studying the technique of a recently restored painting<br />

is being able to see the paint layer rather than trying to imagine it, hidden<br />

under layers of dark <strong>and</strong> obscuring varnish. In the case of The Prodigal<br />

Son, the technique proved to be a great deal more spontaneous <strong>and</strong> the<br />

execution more rapid than it was thought to be prior to restoration. 2<br />

<strong>Technique</strong><br />

a. The support<br />

The Prodigal Son was painted on a well-constructed oak panel which<br />

measures 109.75 x 158.2 cm. It is composed of 5 horizontal planks which<br />

are butt-joined (ill. 1).<br />

1. 22 - 23 cm<br />

2. 22 cm<br />

3. 20.75 cm<br />

4. 24.75 cm<br />

5. 20.50 cm<br />

Ill.1 The dimensions <strong>and</strong> position of the planks, recto side.<br />

All the planks are quarter-sawn; the fourth plank is partly false quartersawn,<br />

where the medullary rays cross the annual rings diagonally. The<br />

wood came from the Baltic region <strong>and</strong> planks 2, 3 <strong>and</strong> 5 are from the same<br />

tree. Dendrochronology has been able to give an earliest felling date of<br />

1613 for the fourth plank, giving the earliest possible creation date as 1615.<br />

However allowing a 15-year average for sap wood rings, the more probable<br />

date would be later, from 16<strong>21</strong> onwards. 3

BULLETIN<br />

BULLETIN<br />

Information about the construction<br />

of the panel is limited by the<br />

presence of a cradle (ill. 2) <strong>and</strong> a<br />

double layer of lead white paint<br />

applied between the elements of<br />

the cradle in1895. 4<br />

The panel must have been planeddown<br />

in order to attach the cradle.<br />

Under the vertical battens, we<br />

can see that areas of the panel<br />

were built-up by pieces of oak of<br />

approximately 4<br />

x 12 cm, glued side by side, presumably to<br />

create a level surface for attaching the fixed<br />

horizontal elements of the cradle (ill. 3). 5<br />

Ill.2 The cradle on the reverse of the panel<br />

The panel has been reduced in size on all<br />

four sides but the presence of the vertical<br />

prepared but unpainted edges on the recto<br />

side, tells us that the amount may be slight as<br />

the painting proper is intact.<br />

The “unpainted edges” or margins correspond<br />

approximately to a rebate of between 3 -7<br />

mm, cut at a right-angle into the vertical<br />

edges on the reverse of the panel (ill. 4). This appears<br />

to be part of the original construction. We had thought<br />

that the rebates were related to the framing but it now<br />

seems probable that they were made to accommodate<br />

temporary grooved battens, or ‘channel edge supports’<br />

that were slid onto the end-grain edges of panels to<br />

prevent warping. 6 A similar rebate can be found on the<br />

reverse of the panel of “Christ <strong>and</strong> the Woman taken in<br />

Adultery” by Rubens in the Musée Royal des Beaux-<br />

Arts, Brussels. 7 The ‘unpainted’ edges of The Prodigal<br />

Son have a ground layer (unlike the Brussels panel).<br />

Ill.3 Detail of where a vertical batten of the<br />

cradle has been removed to show that the<br />

back of the panel had been built up before the<br />

cradle was attached.<br />

It seems that ‘channel edge supports’ may have been put on in the studio,<br />

during the painting process, presumably when the panel began to warp.<br />

This could explain why some paint can be found on the unpainted edge<br />

but a distinct margin, or limit to the paint layer, was made once the battens<br />

were in place.<br />

b. The frame<br />

We have no information about the original frame. The frame in which that<br />

The Prodigal Son is currently shown is of English origin, dating from the<br />

19 th century.<br />

c. The ground<br />

The panel was prepared with what looks like the traditional chalk glue<br />

ground (ill. 5). It is off-white, thinly applied <strong>and</strong> is smooth <strong>and</strong> hard. Very<br />

few samples were taken <strong>and</strong> in the cross-section (ill. 8) the ground appears<br />

to be absent.<br />

The ground continues to the edge of<br />

the panel where the sharpness of the<br />

outline confirms that the panel has<br />

been trimmed. The “unpainted” but<br />

prepared edges of the vertical sides of<br />

the panel were obviously intended to<br />

be covered later by the frame.<br />

No isolation layer was visible. Because<br />

much of the paint layer was thinly<br />

applied, the white ground influences<br />

Ill.5 Detail of the “unpainted” edge or margin.<br />

The white ground can be seen where the frame has<br />

rubbed away the overlying paint layers<br />

the final painting by allowing light to<br />

reflect through even the darker areas,<br />

adding luminosity <strong>and</strong> transparency.<br />

Ill.4 Detail of rebate along the vertical edge

BULLETIN<br />

BULLETIN<br />

d. The imprimatura<br />

A pale grey stripey imprimatura is present but not easily detected. Stripey<br />

imprimatura is characteristic of Rubens panel paintings but it is most<br />

commonly seen in his sketches on panel, such as the recently restored<br />

Triumphal Chariot of Kalloo (KMSKA, inv. no 318),<br />

where the imprimatura is ochre rather than grey.<br />

It is often less apparent in his finished paintings, as<br />

is the case here. It can be seen, however, in the gap<br />

between the painted contours of the wooden post<br />

<strong>and</strong> the sky <strong>and</strong> through the transparent brown<br />

paint of the post (ill. 6). The imprimatura can be<br />

seen more clearly with infrared photography (ill.<br />

7) where it appears to have<br />

been roughly applied with<br />

a wide bristle brush in<br />

horizontal <strong>and</strong> diagonal<br />

directions (2.), changing<br />

to a vertical direction<br />

along the vertical edges.<br />

Ill.6 The grey stripey imprimatura<br />

can be seen in the gap in the paint<br />

between the post <strong>and</strong> the sky.<br />

Rubbed away the overlying paint<br />

layers.<br />

The stripey imprimatura may have acted as an<br />

isolation layer preventing the oil of the paint layer<br />

from sinking into the porous white ground. It<br />

was also a device to give a tonality to the ground<br />

without losing its luminosity.<br />

Ill. 7 The grey stripey imprimatura<br />

is visible under the transparent paint<br />

layer of the tree <strong>and</strong> the wooden post.<br />

e. The underdrawing<br />

No underdrawing was visible or detected by infra-red photography. It is,<br />

in any case, unusual to find underdrawing in Rubens’s finished paintings,<br />

although more common in his sketches. An example, however, can be found<br />

in The Farm at Laeken, (London, The Royal Collection), where “lines of<br />

underdrawing are visible in the arm <strong>and</strong> face of the st<strong>and</strong>ing woman in the<br />

centre” 8<br />

f. The paint layer<br />

Pigments<br />

Analysis: a number of inorganic pigments have been identified by using<br />

PXRF, a non-destructive method of analysis. 9 Organic pigments frequently<br />

used by Rubens, such as red <strong>and</strong> yellow organic glazes, indigo, Cassel earth<br />

<strong>and</strong> bitumen, cannot be identified by this method of analysis.<br />

The following pigments were identified: white lead was identified in the<br />

29 places that were analysed; sienna or possibly umber in the browns with<br />

occasional traces of vermilion; vermilion probably in combination with red<br />

earth for the reds; in the yellow highlights of the hay, lead-tin yellow with<br />

probably a yellow earth. The greens were composed of a mixture of yellow,<br />

probably lead tin yellow <strong>and</strong> a copper containing pigment, such as azurite,<br />

or blue or green verditer. The blues used for clothing contained copper<br />

indicating the use of azurite or blue verditer. However the blue for the sky<br />

could be identified as either indigo or ultramarine / lapis lazuli. Very few<br />

samples were taken from the paint layer. Two samples were taken from<br />

the grey paint on the margin of the left edge. This was to identify the large<br />

white grains that occur throughout the paint layer but predominantly in<br />

the dark area of the roof, on the left side of the picture. Another sample was<br />

taken in the sky to identify the blue pigment that could not be determined<br />

by PXRF.<br />

The ubiquitous white granular pigment was identified as lead white. The<br />

sample taken to analyse the blue pigment in the sky can be seen in crosssection<br />

(ill.8) where ultramarine/<br />

lapis lazuli was identified. The<br />

under-lying grey layer contains<br />

chalk <strong>and</strong> lead white. Originally we<br />

believed it to be the ground layer<br />

but now see it as an intermediate<br />

layer <strong>and</strong> that the ground layer is<br />

missing. 10<br />

Ill.8. Cross-section, taken from the sky with part of a leaf.<br />

The blue pigment was identified as ultramarine / Lapis lazuli.<br />

(Photograph, Antwerp University).

BULLETIN<br />

BULLETIN<br />

g. Method of painting<br />

One of the most remarkable aspects of the technique of this painting is the<br />

apparent speed <strong>and</strong> spontaneity of its execution. The following description<br />

is an attempt to describe the technique, by which way Rubens succeeded<br />

in executing a complex, often thinly painted but detailed composition<br />

while at the same time demonstrating an extraordinary liveliness in his<br />

painting.<br />

Establishing the composition:<br />

It is difficult to know to what extent Rubens had developed the composition<br />

for The Prodigal Son before transferring it to panel. In the absence of any<br />

important changes of composition <strong>and</strong> the fact that areas were reserved<br />

in the paint layer, we should conclude that it was carefully planned. The<br />

composition, in any case, would have been underpinned by detailed<br />

drawings taken from nature, such as his study of A Man Threshing beside<br />

a Wagon, Farm Buildings Behind, ca 1617-18 (J.P. Getty Museum, Los<br />

Angeles). In it we see an identical wagon in front of a similarly thatched<br />

farm building. 11<br />

There is no detectable underdrawing. One of the methods of transferring a<br />

composition to its final support may have been with a material such as black<br />

or other coloured chalk. The following<br />

description may offer an explanation of<br />

why we see no trace. “..it would seem from<br />

the De Mayerne MS that it was customary<br />

to erase, or nearly so, the initial rough<br />

drawing in black chalk before or during<br />

the painting process.” 12<br />

If we look at Rubens’s sketches on panel, he<br />

often used thin grey or warm brown paint<br />

as a brushed drawing over the imprimatura.<br />

This method allows alterations to be easily<br />

adjusted while the composition is being<br />

developed <strong>and</strong> does not disturb any final<br />

transparent or thinly applied paint layer. Another method used by Rubens<br />

to place figures was by painting into a scumble or opaque wet paint. 13 An<br />

Ill.9 The cow’s horns have been provisionally<br />

placed using thin brown fluid paint.<br />

example of the former type of laying in or placing details in The Prodigal<br />

Son, can be seen in the brown lines of the sow’s hind legs <strong>and</strong>, at a later<br />

stage of the painting, where a cow’s horns have been provisionally placed<br />

using thin brown fluid paint (ill.9).<br />

While an example of the latter, wet paint method, can<br />

be illustrated by the painting into the wet paint around<br />

the woman feeding the pigs, where she was originally<br />

placed more to the left <strong>and</strong> her shoulders have finally<br />

been made less broad (ill.10).<br />

Apart from the laying in of the structure of the barn<br />

<strong>and</strong> principle elements of the composition, it would<br />

have been important for Rubens to establish the areas<br />

of light <strong>and</strong> shadow cast by the different sources of<br />

light, daylight <strong>and</strong> c<strong>and</strong>lelight. This would have to be<br />

done in the early stages. The unusually<br />

grainy texture of the paint surface that is<br />

so noticeable on the left of the picture, in<br />

the dark, thinly-painted rafters, is caused<br />

by large grains of lead white pigment.<br />

Ill.10 <strong>Painting</strong> into the opaque wet paint of the<br />

background to place the woman feeding the<br />

pigs. She was originally more to the left <strong>and</strong> had<br />

broader shoulders.<br />

They come from an underlying paint layer that may have been used to lay<br />

in the composition. We do not yet know if the opaque grey paint visible<br />

along the left vertical margin belongs to this laying-in stage but, if so, it<br />

seems plausible that it was used to establish areas of light <strong>and</strong> shadow. (A<br />

detail of the grey paint on the left margin can be seen in ill 5).<br />

Ill.11 Infra-red photography gives a clear image<br />

of the broad brush strokes <strong>and</strong> rapid execution of<br />

the beams <strong>and</strong> rafters in the background.<br />

The painting technique:<br />

Once the composition was in place, the<br />

painting of the background must have been<br />

executed at great speed judging by the broad<br />

brush strokes in the central rafters (ill.11),<br />

<strong>and</strong> by the thin <strong>and</strong> transparent brown<br />

washes applied along the beam that catches<br />

the light (ill.12).<br />

Ill.12 The beam was rapidly executed using<br />

thinly applied transparent brown washes.

BULLETIN<br />

BULLETIN<br />

By comparing a finished detail of the barn with an infrared photograph<br />

of the same detail, we are able to see the spontaneous brush strokes that<br />

underlie some of the final paint layer (ill.13, 14). The hurriedly-applied<br />

dark horizontal brush stroke to the left, near the top edge of the panel,<br />

crossing under the light-coloured roof supports, may have been intended<br />

as another beam. The fact that it is now so<br />

easily visible in the light areas underlines<br />

the artist’s comm<strong>and</strong> of his technique<br />

elsewhere in the painting.<br />

As much as three-quarters of this<br />

composition was painted using tones of<br />

brown paint. Much of it was applied very<br />

thinly <strong>and</strong> transparently as we can see<br />

even in the dark areas of the roof. 14 The<br />

middle <strong>and</strong> foreground are much lighter<br />

in tone <strong>and</strong> in the immediate foreground<br />

the paint is often so thinly applied that the white ground itself is barely<br />

covered. An idea of how the painting stage developed can be seen by a<br />

slight change of position in the skirt of the old woman holding a c<strong>and</strong>le. 15<br />

Ill.13 Detail of the barn in normal light<br />

Originally she was painted advancing<br />

further into the barn. A few highlights<br />

corrected the position, but the firm linear<br />

brush strokes of her original skirt remain<br />

clearly visible (ill.15).<br />

Ill.15 Shows, the firm linear brush strokes of an earlier<br />

position of the old woman’s skirt ( just to the right)<br />

Ill.14 Infra-red photograph showing detail of<br />

the barn where the vigourous brush strokes of<br />

the underlying paint layer are clearly visible.<br />

The old woman’s head is an example of painting directly into the dark<br />

background paint while it was still wet. It is also a remarkable example<br />

of rapid <strong>and</strong> sure technique. By adding a few strokes of brown glaze <strong>and</strong><br />

white highlight he created her headdress <strong>and</strong> face. The whole is brought<br />

to life by the dramatic red highlights under her chin <strong>and</strong> nose from the<br />

reflected light cast up by her c<strong>and</strong>le (ill.16). Elsewhere,<br />

however, reserves in the paint layer were made to make<br />

use of the lightness of the white ground <strong>and</strong> to some<br />

extent, the effect of the stripey imprimatura. Examples<br />

of reserves in the foreground include the two pigs on<br />

the left, (but not the hind leg of the sow), the wooden<br />

supporting post of the barn <strong>and</strong> the Prodigal Son’s head<br />

<strong>and</strong> body. The tree trunk was reserved to the height of<br />

the first fork, after which the branches were painted<br />

over the blue sky. Even the belt of the bag hanging in<br />

the centre of the picture, over the cows, was carefully<br />

reserved. The blue sky was painted up to<br />

either side of it, although the l<strong>and</strong>scape had<br />

already been sketched in behind (ill.17).<br />

The belt is a device which, together with the<br />

sight lines of the architecture of the barn, is intended to draw the onlooker’s<br />

eye into the picture, through the barn <strong>and</strong> out to the countryside beyond. 16 .<br />

The sense of depth was further enhanced by a glaze of natural ultramarine,<br />

a vivid blue, added to the sky line just above the trees to the right of the<br />

belt. The choice of ultramarine / lapis lazuli as the blue pigment for the<br />

rest of the sky is interesting as it was very<br />

expensive. Azurite, which tends to have a<br />

greener tonality than natural ultramarine,<br />

has been used as the blue pigment in the<br />

rest of the painting. 17 Perhaps Rubens<br />

decided that only natural ultramarine<br />

could give the intense blue of day-light<br />

that he needed to contrast with the<br />

artificial <strong>and</strong> warmer c<strong>and</strong>le-light in the<br />

barn.<br />

Ill.16 The old woman’s head was painted<br />

into the wet paint of the background.<br />

Ill.17 The belt was carefully reserved against the<br />

sky. The blue paint was added to either side of it.

BULLETIN<br />

BULLETIN<br />

Much of The Prodigal Son was executed alla prima. The rapid execution,<br />

already noted in the broad-brush treatment of the background, can also be<br />

illustrated by the numerous examples of painting wet paint into wet paint.<br />

These include the cock’s tail painted with three rapid brush strokes into<br />

the wet background paint (ill.18), working<br />

into wet impasto paint with the stub-end of<br />

the brush to imitate basket weave (ill.19),<br />

painting a branch through the impasto paint<br />

in the tree (ill.20) <strong>and</strong> the st<strong>and</strong>ing heifer’s<br />

rump, where the wet paint of the short<br />

diagonal brush strokes have been dabbed<br />

with a brush leaving round textured marks<br />

in the wet paint (ill. <strong>21</strong>).<br />

Ill.18 The cock’s tail was painted with three<br />

rapid brush strokes into the wet background<br />

paint.<br />

Ill.<strong>21</strong> The short diagonal<br />

brush strokes have been<br />

dabbed with the end<br />

a brush making round<br />

textured marks into the<br />

wet paint<br />

Ill.23 The white impasto paint of the<br />

cock’s neck feathers, was applied with a<br />

finely pointed brush.<br />

Ill.26 By comparison the<br />

hind legs have an almost<br />

sketchy execution.<br />

Of the many types of brush strokes that<br />

are clearly visible in the paint layer, a few<br />

examples are: in the thatch of the barn roof,<br />

where the brush strokes can be seen in the<br />

thinly applied, transparent paint (ill.22).<br />

The cock’s neck feathers, (ill.23) where<br />

white impasto paint has been applied with<br />

rapid strokes of a finely pointed brush, <strong>and</strong><br />

the horizontal brush strokes in the barn,<br />

where a more flat-ended brush was used (ill.24).<br />

Rubens has employed an almost graphic way<br />

of painting the cows <strong>and</strong> the pigs, where<br />

the diagonal brush strokes are similar to a<br />

hatching technique used in drawing. These<br />

lines follow the form <strong>and</strong> create a sense of<br />

volume using a minimum of material. The<br />

two horses were painted using a similar<br />

Ill.20 <strong>Painting</strong> a branch through the impasto<br />

paint in the tree.<br />

Ill.19 “Drawing” into the wet impasto<br />

with the stub-end of the brush<br />

to imitate the basket weave.<br />

Ill.24 Horizontal brush<br />

strokes, where a more flatended<br />

brush was used.<br />

Ill.22 Brush strokes are clearly visible in the thinly<br />

applied paint of the thatch of the barn roof.<br />

technique, but the areas of light <strong>and</strong> shade of the grey<br />

stallion were given more substance by the addition of<br />

a smooth <strong>and</strong> fluid paint layer, either of transparent<br />

brown in the shadow or pale grey in the light areas. The<br />

hindquarters seem to have been underpainted with a<br />

dark grey paint applied in irregular circular patterns,<br />

over which the lighter grey was added to produce a<br />

subtle dappled effect. Highlights were added in short<br />

diagonal strokes while white impasto paint completed<br />

highlights to the tail.<br />

Some parts of The Prodigal Son were painted with<br />

attention to detail, particularly in the centre while in<br />

areas that were less likely to be noticed the execution is<br />

particularly free <strong>and</strong> almost sketchy. Thus the central

BULLETIN<br />

BULLETIN<br />

heifer’s head is painted with a high degree of finish<br />

(ill. 25) while her hind legs, in shadow, have a more<br />

summary, almost sketchy execution (ill. 26).<br />

This is a painting that can best be appreciated by st<strong>and</strong>ing<br />

at some distance. As we have seen Rubens employed<br />

a number of devices to enhance the element of space<br />

within this composition. The final brush strokes may<br />

well have been the rapidly applied highlights added<br />

to the fork in the foreground <strong>and</strong> some of the more<br />

hurriedly applied cobwebs in the rafters, again with the<br />

idea of drawing us into this remarkable painting.<br />

Susan Farnell<br />

Ill.25 The central heifer’s<br />

head is painted with a high<br />

degree of finish.<br />

Rubens is believed to have retouched The Prodigal Son later on in his life.<br />

The painting was, in any case, in his possession at the time of his death.<br />

Apparently the artist was unable to resist the temptation of making<br />

adjustments to the composition. Unlike the other faces in the painting,<br />

that of the stable h<strong>and</strong> on the far left is executed in very expressive, patchy<br />

brushstrokes. This style does not correspond with the smooth, calligraphic<br />

approach that is so characteristic of Rubens’s work from around 1618. The<br />

white horse also appears to have been retouched. Its head, unlike the rest of<br />

its body, was not kept in reserve, but sketched onto the brown background<br />

colour in a few quick light brushstrokes. The hind end <strong>and</strong> tail have been<br />

accentuated with some touches of white paint, so that the horse catches<br />

more light <strong>and</strong> thereby draws the viewer’s attention. Also, Rubens added<br />

some volume to the right flank of the brown horse. The purpose of these<br />

corrections was possibly to achieve a better balance in the composition.<br />

Without the alterations, clearly the most illuminated areas in the picture<br />

were on the right-h<strong>and</strong> side.<br />

In the print after the painting by Schelte Adamsz Bolswert, one notices<br />

that the large deciduous tree in the farmyard was originally a rather measly<br />

pollard willow. We were able to determine by means of an infrared image<br />

that Rubens reserved the shape of this pollard willow in the paint layer, as<br />

we notice the stripy imprimatura through the thinly applied paint of the<br />

trunk (ill. 7). This is however not the case for the rest of the trunk <strong>and</strong> the<br />

branches, which were painted over the greyish-blue sky. Perhaps Rubens<br />

chose to add a lush crown to soften the transition from the bright sky<br />

to the angular contours of the barn. Rubens is known to have retouched<br />

other paintings which he felt no longer tied in with his artistic aims. In<br />

quite a few cases, such corrections involved adjustments <strong>and</strong> sometimes<br />

enlargements of the support. 18<br />

There are hardly any other paintings of this size in Rubens’s oeuvre that have<br />

been painted as sketchily as The Prodigal Son. The explanation probably<br />

lies in the fact that the barn, which takes up most of the composition, is<br />

shrouded in twilight, <strong>and</strong> Rubens tended to provide far less detail in the<br />

darker areas of his paintings than in the brighter ones. The only comparable<br />

“cabinet picture” is The Calydonian Boar Hunt in Los Angeles (c. 1611), 19<br />

in which the boar as well as the foreground <strong>and</strong> background are also<br />

rendered rather sketchily. There are however a<br />

number altarpieces, including the Adoration of<br />

the Magi in Antwerp (1624), the St. Ildefonso<br />

Triptych in Vienna (1630-31) <strong>and</strong> the Adoration<br />

of the Magi in Cambridge (1633-34), which<br />

were executed with similar economy of means.<br />

The same holds for the monumental Hercules<br />

Drunk in Dresden (1613-14). 20 Rubens executed<br />

these large paintings himself, quickly, alla<br />

prima, with medium-rich paints that he could<br />

apply thinly to the panels. As a consequence,<br />

the chalk glue ground is visible through the<br />

paint layer in many places in these works. As<br />

in The Prodigal Son, individual brushstrokes<br />

in the abovementioned paintings are visible<br />

Ill. 7 The grey stripey imprimatura is visible under the<br />

transparent paint layer of the tree <strong>and</strong> the wooden post.

BULLETIN<br />

BULLETIN<br />

mostly in the shaded areas. The technique of scratching into wet paint<br />

with the back of a brush, which Rubens applied in the basketwork in The<br />

Prodigal Son, is rather rare in his oeuvre (unlike in the work of Rembr<strong>and</strong>t,<br />

Jan Lievens, Aert van der Neer <strong>and</strong> Arent de Gelder). <strong>21</strong><br />

Nico Van Hout<br />

1) The following documentation was carried out:<br />

Dendrochronology, see note 3.<br />

Infra-red Photography, (Adri Verburg).<br />

Infra-red Photography with false colour, (Adri Verburg).<br />

UV photography (Susan Farnell).<br />

Photographic documentation (Susan Farnell <strong>and</strong> Adri Verburg).<br />

Non-destructive inorganic pigment analysis (PXRF), see note 9.<br />

Cross-sections <strong>and</strong> analysis, see note 10.<br />

X radiographs were not taken because of the lead white on the reverse of the panel<br />

2) John.Smith, Catalogue Raisonné, 11, 804; 1X, p.300, N° 205. “ …the picture is painted with extreme<br />

care..”<br />

3) P. Klein (Zentrum Holzwirtschaft an der Universität Hamburg), Report on the<br />

dendrochronological analysis of the panel, 17.3.2005.<br />

4) Archives of the KMSKA. The painting was acquired for the Museum in 1894, bought from<br />

Gauchez, Paris. The earliest treatment report that was found in the archives dates from 14 th March<br />

1895. It is a proposition by Maillard to re-glue the panel, to make a cradle <strong>and</strong> apply a double layer of<br />

ceruse to the back of the panel. (Archive dossier E 18f ). 1895 Maillard Archief, box E6,E8d, E8e. 1896<br />

Maillard Archief, E8e. E18f 1937 No information, just reference. 1946 C. Bender, information, nothing<br />

specific. 1953 Just reference. 1977 Just reference. Also mentioned in two reports of Benders in 1994<br />

<strong>and</strong> 1996.<br />

5) J.A. Glatigny, The support was treated in 2004. The sliding elements of the cradle needed to be<br />

unblocked prior to restoration, to prevent strain on the panel. The two horizontal breaks in the panel<br />

<strong>and</strong> all but one of the numerous short splits along the vertical edges were stable.<br />

6) In many cases the ‘channel edge supports’ would have been in place before the ground was applied<br />

to the panel <strong>and</strong> only removed once the painting was to be framed; in that case the panel would have<br />

two unpainted <strong>and</strong> ungrounded edges <strong>and</strong> a ‘barbe’. I am grateful to Christina Currie for information<br />

concerning ‘channel edge supports’. For more detailed information on this subject see D. Allart et<br />

C. Currie, ‘Analysis of selected works by Pieter Bruegel the Elder <strong>and</strong> Pieter Brueghel the Younger’,<br />

Brussels, Royal Institute of Cultural Heritage, collection Scientia artis (forthcoming).<br />

7) This work was also painted on a panel constructed with horizontal planks. The recto side has two<br />

ungrounded-edges <strong>and</strong> a “barbe” indicating that the ground was applied when the vertical sides<br />

were held in ‘channel edge supports’. These must have been removed during painting as the paint<br />

layer overlaps the “barbe” onto the wood of the unpainted-edge. I am grateful to Hélène Dubois for<br />

this information; detailed information gathered during the Rubens Project of the Musées Royaux<br />

des Beaux-Arts de Belgique in Brussels, should be available at the end of next year, probably as a<br />

database/web site.<br />

8) C. Brown, Making <strong>and</strong> Meaning: Rubens’s L<strong>and</strong>scapes, exh. cat., London, 1996, p. 117.<br />

9) Pigment analysis, using PXRF (Keymaster Tracer <strong>III</strong>-V), was carried out by Geert van der Snickt<br />

<strong>and</strong> Koen Janssens, Antwerp University, department of Chemistry. The identification of inorganic<br />

pigments by this method is made by a process of deduction: in this case, by comparing the chemical<br />

elements present in a sample of approx. ½ cm² with those of a comparable colour, from the limited<br />

number of pigments available to artists in the 17 th century. Secondary colours such as green could be<br />

of a single mineral origin but were often made of mixtures of blue <strong>and</strong> yellow thus complicating the<br />

identification of the pigments used. XRF identifies elements through the depth of the paint layer <strong>and</strong><br />

beyond, not just on the surface, which may lead to results that are difficult to interpret.<br />

10) Koen Janssens, G. van der Snickt, cited note 9, Cross-section <strong>and</strong> SEM <strong>and</strong> analysis by XRD.<br />

11) See also Study of an Ox, ca. 1618, Albertina, Vienna (8253); the central heifer in the Prodigal Son is<br />

very similar to this study but in reverse position. A similar ox appears in The Farm at Laeken, London,<br />

The Royal Collection, (RCIN 405333). In the same painting the position of the cow that is lying-down

BULLETIN<br />

is close to one in The Prodigal Son, but in reverse, as is the man on horse back, leading another horse<br />

to water.<br />

12) J.Plesters, ‘“Samson <strong>and</strong> Delilah”: Rubens <strong>and</strong> the Art <strong>and</strong> Craft of <strong>Painting</strong> on Panel’, National<br />

Gallery Technical Bulletin 7, 1983 p 38, note <strong>21</strong>.)<br />

13) Both these methods can be seen in his sketch of the Triumphal Chariot of Kalloo, <strong>Koninklijk</strong><br />

Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp, inv. no 318.<br />

14) However in some areas where dark brown or black paint was applied more thickly, premature<br />

drying cracks can be seen in the paint layer. This problem occurs in other paintings by Rubens <strong>and</strong><br />

may be due to a bituminous content in the paint. See R. White, ‘Brown or Black Organic Glazes,<br />

Pigments <strong>and</strong> Paints’, National Gallery Technical Bulletin, 10, 1986, pp 58-71, p. 62, for problems<br />

caused by bitumen <strong>and</strong> aspheltum in the drying of oil film, <strong>and</strong> p.65, lignites <strong>and</strong> peats as principle<br />

source of Cologne earth, retards drying in oil films. J. Kirby, ‘The Painter’s Trade in the Seventeenth<br />

Century: Theory <strong>and</strong> Practice’, National Gallery Technical Bulletin, 20, 1999, p.38 on Cassel or Cologne<br />

earth, <strong>and</strong> other dark brown translucent pigments used by Rubens <strong>and</strong> Van Dyke; in same volume R.<br />

White, ‘Van Dyke’s Paint Medium’, pp. 84-88, esp. p. 84 with reference to paint film defects <strong>and</strong> also<br />

brown-black tars, pitches <strong>and</strong> bistre.<br />

15) A slight change of position can be seen in infrared photography where the winnowing fan,<br />

hanging on the wall, seems to have been smaller. There is a deformation in the panel near the top<br />

of the basket. We cannot be sure whether this is an old area of damage or perhaps an original repair<br />

in the panel. We are also not sure of the reason for losses in the paint layer of the skirt of the young<br />

woman feeding the pigs. Before restoration, they were thought to be due to flaking paint. This proved<br />

not to be the case but the paint has been damaged in localised areas.<br />

16) The perspective has been slightly corrected in the engraving of The Prodigal Son by Schelte à<br />

Bolswert (reproduced in M. Rooses, L’Oeuvre de P.P. Rubens, Antwerp 1888, vol. 11, pl. 89). There are<br />

a number of other variations, some of which include: the cows being carefully tethered, one of the<br />

mare’s forelegs is visible, the winnowing fan on the wall is smaller; the main tree is pollarded. The<br />

engraver has misunderstood the construction of the roof in the top corner above the manger, where a<br />

diagonal roof support has become a rafter.<br />

17) Kirby 1999, cited in note 12, pp 35-36.<br />

18) Cf. G. Martin, ‘Two closely related l<strong>and</strong>scapes by Rubens’, in The Burlington Magazine, 757,<br />

CV<strong>III</strong> (April 1966) pp. 180-184; R. Bruce-Gordon, ‘Rubens’s “L<strong>and</strong>scape by Moonlight”: technical<br />

examination, in The Burlington Magazine, CXXX (August 1988), pp. 591-596; V. Poll-Frommel, K.<br />

Renger, J. Schmidt, ‘Untersuchungen an Rubens-Bildern: Die Anstückungen der Holztafeln’, in<br />

Jahresbericht Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, 1993, pp. 24-35; K. Renger, ‘Anstückungen bei<br />

Rubens’, in Die Malerei Antwerpens: Gattungen - Meister -Wirkungen (Vienna, 1993), pp. 157-160;<br />

K. Renger, ‘Rubens-stücke. Die Anstückungen von Münchner “Silen” und “Schäferszene”’ Wallraf-<br />

Richartz-Jahrbuch, LV, Festschrift für Prof. Dr. Justus Müller Hofstede (Cologne, 1994), pp. 171-184;<br />

N. Van Hout, ‘A second self-portrait in Rubens’s “Four Philosophers”, in The Burlington Magazine,<br />

CXLII, 2000, pp. 694-697.<br />

19) Calydonian Boar Hunt, Los Angeles, The J.P. Getty Museum, inv. no. 2006.4.<br />

20) Adoration of the Magi, KMSKA, inv. nr. 298 (Jaffe 1980, no. 780); St. Ildefonso Triptych, Vienna,<br />

Kunsthistorisches Museum, inv. 678/ 698 (Jaffé 1980, no. 998); Adoration of the Magi, Cambridge,<br />

King’s College Chapel (Jaffé 1980, no. 1095); Hercules Drunk, Dresden, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister,<br />

inv. no. 987 (Jaffé 1980, no. <strong>21</strong>5).<br />

<strong>21</strong>) See also Rubens’s St George Slaying the Dragon (Madrid, Prado, inv. no. 1644; Jaffé 1980, no.<br />

69). Here, the hairs of the horse’s tail are also scratched into the dark paint. As a result, the beige<br />

underpainting comes to the surface.