Kimberley Appropriate Economics Interim Report - Australian ...

Kimberley Appropriate Economics Interim Report - Australian ...

Kimberley Appropriate Economics Interim Report - Australian ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Kimberley</strong> <strong>Appropriate</strong> Economies Roundtable<br />

Fitzroy Crossing 11-13 October 2005<br />

<strong>Interim</strong> <strong>Report</strong><br />

December 2005

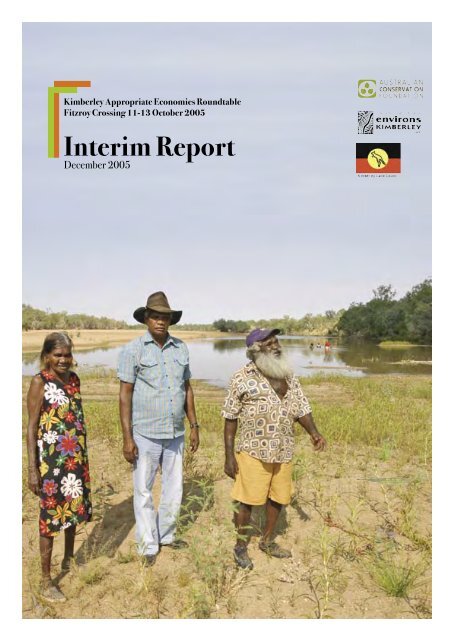

Front cover photograph shows Daisy Andrews, Dylan Andrews, and Joe Brown at the old crossing on the Fitzroy River.<br />

Back cover photograph shows the Fitzroy River in the dry season.<br />

This report is an <strong>Interim</strong> <strong>Report</strong>. Publication of the Final <strong>Report</strong> of the <strong>Kimberley</strong> <strong>Appropriate</strong> Economies Roundtable<br />

will constitute the Proceedings of the Roundtable.<br />

Design and layout by Jane Lodge.<br />

Photography by Gene Eckhart, Joseph Fox, Steve Kinnane, Maria Mann, and Justin McCaul.<br />

This report and the images it contains © 2005 <strong>Kimberley</strong> Land Council, Environs <strong>Kimberley</strong>, and the <strong>Australian</strong> Conservation Foundation.

<strong>Kimberley</strong> <strong>Appropriate</strong> Economies Roundtable<br />

Fitzroy Crossing 11-13 October 2005<br />

<strong>Interim</strong> <strong>Report</strong><br />

December 2005

CONTENTS<br />

OPENING QUOTES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2<br />

INTRODUCTION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .8<br />

BACKGROUND TO THE ROUNDTABLE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .9<br />

OBJECTIVES OF THE ROUNDTABLE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10<br />

ROUNDTABLE FORMAT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11<br />

SUMMARY OF WHAT HAPPENED AT THE ROUNDTABLE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12<br />

DAY ONE<br />

First Big Group Session ..............................................................................12<br />

Opening Speeches .....................................................................................12<br />

Presentations .............................................................................................13<br />

Small Group Workshops .............................................................................13<br />

Land Management .................................................................................................... 13<br />

Tourism .................................................................................................................... 13<br />

Pastoralism .............................................................................................................. 14<br />

Agriculture ............................................................................................................... 14<br />

Culture and Art ......................................................................................................... 14<br />

Partnerships in Conservation ...................................................................................... 14<br />

Small Group Workshop Discussions ............................................................14<br />

DAY TWO<br />

Second Big Group Session ..........................................................................15<br />

Small Workshop Sessions ...........................................................................15<br />

Last Big Group Session ..............................................................................15<br />

SIGNIFICANCE OF THE ROUNDTABLE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16<br />

THE NEXT STEPS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17<br />

OUTCOMES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18<br />

STATEMENT OF PRINCIPLES ........................................................................18<br />

KEY ACTIONS ................................................................................................19<br />

Discussion of Key Actions in the Small Group Workshops .............................19<br />

Summary of Key Actions .............................................................................21<br />

APPENDICES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27<br />

Appendix A Presentations at the Roundtable . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29<br />

Appendix B Media <strong>Report</strong>s . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 61<br />

Appendix C Roundtable Program . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 69<br />

Appendix D List of Participants . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 73<br />

Appendix E Summary of Roundtable Evaluations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 75<br />

Appendix F Table of Presenters . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 77<br />

Appendix G List of Papers Commissioned for the Final <strong>Report</strong> . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 77<br />

Appendix H Roundtable Sponsors and Supporters . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 78<br />

Appendix I List of Acronyms . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 79

Why would you?<br />

The first three words that came into my mind when I<br />

heard about this forum, are ‘Why would you?’<br />

Sometimes people like myself and others feel<br />

powerless when we try to articulate change and<br />

the needs of our communities, when our advice<br />

and input into conferences like this one here, falls<br />

on deaf ears.<br />

And I see our communities struggling with<br />

poverty, and agencies struggling with a diminishing<br />

public sector resource base and an ever increasing<br />

market driven economy that wants access to take<br />

natural resources like iron ore, like uranium, and<br />

like water out of this river.<br />

And this market is demanding we use<br />

our resources, and that’s the big conflict<br />

I see in the <strong>Kimberley</strong> for our Elders<br />

- fighting for a cultural asset, (while) the<br />

market looks at that asset as an opportunity<br />

to make money.<br />

But Aboriginal people are supreme optimists,<br />

they’re survivors. They’re here, they’re<br />

not going to move from the Fitzroy Valley.<br />

You’re not going to move the Miriuwung<br />

people, the Karajarri people. That’s their<br />

country.<br />

That if you can start<br />

with one person, it<br />

can grow to two, it<br />

can grow to three<br />

and eventually,<br />

hopefully, it will<br />

grow to 600 people<br />

— motivation for<br />

Bunuba people to<br />

start thinking about<br />

their own wellbeing.<br />

And suddenly everyone<br />

realises after<br />

2

talking about the canal (taking water from the<br />

Fitzroy River to Perth) that you are not only<br />

dealing with the river, you are also dealing with<br />

the people.<br />

And I think that is the challenge – (to get that)<br />

real connection between the integrity of law and<br />

culture - and the industry base.<br />

So we have to find a way as Aboriginal people,<br />

and non-Aboriginal people - as an <strong>Australian</strong><br />

community - to find a way to create what this<br />

conference is about – appropriate sustainable<br />

economies.<br />

This conference can continue, even if it is only<br />

an inch at a time, to build on what’s been done,<br />

to build opportunities to develop sustainable<br />

projects – but never forgetting that intrinsic<br />

value that Aboriginal people place on their lands<br />

and law and culture. That’s got to underpin<br />

everything.<br />

Others want to help make a glue so that all<br />

together as people – not as opposition, or as<br />

black or white, (we can) value this country,<br />

value the well-being of our families, and (work<br />

to relieve) the terrible situation of poverty<br />

Aboriginal people are in. If we can alleviate that<br />

without destroying our culture and our country,<br />

then this Roundtable will have certainly done<br />

well if this is the first step.<br />

Joe Ross, Bunuba Traditional Owner and Community Leader<br />

Taken from his Roundtable opening speech<br />

Wunyumbu<br />

When the world was soft, Wunyumbu was fishing in Mijirayikan<br />

billabong. A huge serpent rose up, and Wunyumbu speared the<br />

serpent and jumped on its back. He rode on the serpent,<br />

traveling east, creating the Fitzroy River system of<br />

plants and animals as he went. All things grow<br />

from this creation of the river.<br />

This is the foundation of our identity. The<br />

Fitzroy River is a part of us and we are a part<br />

of the Fitzroy. If we look after the Fitzroy, it<br />

will look after us. It is time for us to show our<br />

responsibility and look after it for our kids and<br />

their kids - all people, black and white.<br />

As we move into the modern context, we have to become<br />

engaged with the ‘mainstream’ community. We have to speak<br />

clearly and strongly about our beliefs, values, and aspirations<br />

for country.<br />

The <strong>Kimberley</strong> Land Council has been actively<br />

involved in developing a clear picture of what<br />

country means to us, and what we must do to care for<br />

it. The centre of this picture is culture, rights, and<br />

responsibilities. Culture, tells us ‘who we are’ - it is our<br />

foundation.<br />

3

From our culture, we have certain rights to<br />

country, and also certain responsibilities to<br />

look after country, both the physical and living<br />

environments. This includes spirituality,<br />

cultural identity, history, economy, and<br />

responsibility, and forms the basis for society<br />

and life. Keeping country healthy includes<br />

keeping people healthy.<br />

The future must include recognition and<br />

involvement of <strong>Kimberley</strong> Aboriginal people<br />

in managing and setting directions for<br />

country. We must maintain, rehabilitate, and<br />

protect country, and avoid environmental<br />

problems before they occur.<br />

We recognize that in modern times we have<br />

to make a new sort of living from our country,<br />

but can be no sustainable living from country<br />

that is unwell.<br />

We need to have faith in our abilities to<br />

build the future of our choosing. We need<br />

the courage to back our initiative, our selfreliance,<br />

our self-expression, so that we<br />

can build responsible enterprises that are<br />

economically and environmentally viable,<br />

that respect our culture.<br />

Wayne Bergmann, Nyikina man and Executive Director,<br />

<strong>Kimberley</strong> Land Council<br />

Taken from his Roundtable keynote speech<br />

The aspirations<br />

of our people<br />

This is a very special and unusual gathering.<br />

The people here come from a<br />

great diversity of backgrounds<br />

and experience. No govern–<br />

ment department could<br />

assemble such a group.<br />

To bring all these people<br />

together requires us to think<br />

broadly and inclusively. It<br />

also requires a depth and<br />

breadth of local and regional<br />

knowledge, which is worth<br />

more than gold.<br />

We are meeting for two<br />

simple reasons: a shared love<br />

of country and a desire to see the<br />

<strong>Kimberley</strong> prosper.<br />

The <strong>Kimberley</strong> is special<br />

because much of it is<br />

unspoiled. We are in the<br />

happy position of being able<br />

to avoid the worst mistakes made elsewhere. The<br />

Fitzroy River means abundance: abundance of<br />

water during the wet season, abundance of fish<br />

and food, abundance of birds and other wildlife.<br />

To its indigenous people it means even more.<br />

The Fitzroy is a system of natural prosperity,<br />

and any serious interference with its flow could<br />

only reduce its abundance.<br />

Companies wanting to establish a big business in<br />

the <strong>Kimberley</strong> usually either consult Indigenous<br />

people - not always with the results they had<br />

anticipated, -or claim that their enterprise<br />

will benefit Aboriginal people by providing<br />

employment. Aboriginal people may be forgiven<br />

for responding less than ecstatically.<br />

If you are a traditional owner of a part of this<br />

country, a place you have known intimately and<br />

lived in all your life, as your ancestors have done<br />

before you, how are you going to feel about<br />

giving up your rights to that place, seeing it laid<br />

waste, and then being offered a job on it with the<br />

4

industry that has destroyed it?<br />

Money alone does not solve social problems. It<br />

does not solve poverty. Big business, charity,<br />

or welfare do not solve poverty. What solves<br />

poverty is personal enterprise and initiative,<br />

pride and independence, belief in the future,<br />

and a society that fosters these things.<br />

Environs <strong>Kimberley</strong> has helped to drive this<br />

forum because we have faith in the future. We<br />

see the <strong>Kimberley</strong> as a region where nature and<br />

culture are valued, protected, and given priority<br />

in decisions about development; and where<br />

small-scale, environmentally friendly industries<br />

and enterprises are encouraged. As a group<br />

advocating change we accept the challenge to<br />

actively promote better ways of doing business.<br />

So, what sort of enterprises are we looking for<br />

in the <strong>Kimberley</strong>? Some of the participants<br />

in this conference are already engaged in<br />

environmentally friendly enterprises, and with<br />

a commitment motivated by far more than just<br />

the income. But take heed: all such enterprises<br />

require traditional lands and the species that<br />

live on them to remain intact.<br />

Aboriginal people have recently been active<br />

in fire control, and there is opportunity for<br />

other environmental projects on country like<br />

rehabilitation or control of feral animals and<br />

the like. It is time for such important activities<br />

to be properly valued and underwritten by our<br />

society.<br />

We are asking government to listen carefully to<br />

the messages coming out of this forum. We are<br />

asking it to share our vision, to support those<br />

initiatives that enhance the nature and culture<br />

of our region, the way of life here, and the<br />

aspirations of its people.<br />

Pat Lowe, Founding Member and Secretary, Environs <strong>Kimberley</strong><br />

Taken from her Roundtable purpose speech<br />

Making<br />

a good<br />

living from<br />

our country<br />

Traditional Owners of the <strong>Kimberley</strong> have a great<br />

interest in what happens on our country. We face<br />

significant pressures to allow development,<br />

sometimes at any cost. Some people even want to<br />

take <strong>Kimberley</strong> water for Perth people<br />

to keep their lawns green!<br />

5

We have won some battles, at least for the<br />

moment, like keeping cotton out of the West<br />

<strong>Kimberley</strong>, and we’ve had some good friends<br />

like Environs <strong>Kimberley</strong> and the ACF fighting<br />

beside us. But you can’t go from one battle to<br />

another. You need to develop a plan for the<br />

future, you need to set down what your goals<br />

are and how you will achieve them.<br />

The <strong>Kimberley</strong> Land Council has developed a<br />

vision from when it was established, 25 years<br />

ago:<br />

“The <strong>Kimberley</strong> Land Council is a community<br />

organisation, working for and with Traditional<br />

owners of the <strong>Kimberley</strong>, to get back country,<br />

to look after country, and to get control of our<br />

future.”<br />

This vision forms the basis of all the decisions<br />

we make and all the activities we do.<br />

Part of our vision is to look after country. We<br />

have set up a Land and Sea Management Unit to<br />

do this, with its own Vision Statement:<br />

“The <strong>Kimberley</strong> Land Council’s Land and Sea<br />

Unit assists the community to keep country<br />

and culture healthy, get good social, economic,<br />

environmental, and cultural outcomes, and<br />

maintain strong connection to country for future<br />

generations.”<br />

Aboriginal people have always made a good<br />

living from our country, but over the last 200<br />

or so years we have been put to one side in<br />

the development of the region. Now, through<br />

changes in legislation and public thinking, we<br />

are starting to regain control over our lives and<br />

our country.<br />

We are not anti development, but there are<br />

certain things that must be protected. We don’t<br />

agree to every idea that anyone has. We have<br />

fought off cotton, and we are responding to<br />

ideas to take our water from the Fitzroy River.<br />

The KLC has a responsibility to secure the<br />

economic future of <strong>Kimberley</strong> Traditional<br />

Owners. We have started a Sustainable<br />

Development Trust to help with appropriate<br />

activities and enterprises. The Trust’s purpose<br />

is to relieve social and economic disadvantage,<br />

and to pursue sustainable economic and<br />

business opportunities for <strong>Kimberley</strong><br />

Aboriginal people.<br />

We welcome this roundtable, and are pleased<br />

to be involved with it. We know it is important<br />

to give local people, and especially Aboriginal<br />

people, a leading role in decisions about<br />

development of the <strong>Kimberley</strong>. We all want to<br />

find ways to keep control of our lives and our<br />

future, and at the same time protect our culture<br />

and our environment.<br />

This Roundtable will help us set down ways that<br />

we can make a living from the country, ways<br />

that work with country, and protect country for<br />

our future generations. The things you say here<br />

will help to set the direction for the future. This<br />

is an important job that we all have, and I thank<br />

you for your contribution.<br />

Tom Birch, Chairman, <strong>Kimberley</strong> Land Council<br />

Taken from his Roundtable purpose speech<br />

6

If you look at<br />

the Earth from<br />

space, you can’t<br />

see the economy<br />

In this very special region, it is hard not to feel<br />

the spirits of those who have gone before us.<br />

As a scientist, I know the significance of this<br />

region. The Fitzroy basin alone has 37 fish<br />

species, half of them found only in this region,<br />

and a remarkable 67 known species of water<br />

birds. The wetlands are replenished by the<br />

annual wet season flood.<br />

The region is important to the whole world<br />

because of its people and their culture, the land<br />

and the sea, the plants and the animals. But<br />

coming to this place has reminded me that it<br />

is more than a physical region with important<br />

biological features. It is a place of belonging,<br />

of physical and spiritual sustenance. If we don’t<br />

look after this country, sooner or later it will<br />

bite us on the backside. In southern parts of<br />

Australia, the teeth-marks are now visible, the<br />

inevitable consequences of failing to look after<br />

the country.<br />

I don’t need to remind Indigenous communities<br />

of the importance of getting our priorities<br />

right and putting economic development in<br />

perspective. The Western model puts undue<br />

emphasis on the economy at the expense of<br />

social and ecological considerations. This<br />

model concludes that social and environmental<br />

problems can always be solved if the economy is<br />

strong.<br />

But this model<br />

isn’t working.<br />

Successive<br />

reports show<br />

that we are<br />

not using<br />

natural<br />

resources<br />

sustainably.<br />

We need a<br />

new model.<br />

If you look<br />

at the Earth from space, you can’t see the<br />

economy; you see the thin membrane that<br />

supports life and some of the physical features<br />

that separate different human societies, like<br />

oceans and mountain ranges.<br />

The natural systems give us the things we<br />

really need: breathable air, drinkable water,<br />

the capacity to produce our food, our sense of<br />

cultural identity and spiritual sustenance. So<br />

this Roundtable is not just important for the<br />

<strong>Kimberley</strong>. It is the way we should think about<br />

economic development for the whole country.<br />

The vision of a sustainable future is utopian,<br />

but that has been said of all important reform<br />

movements. Change happens because<br />

determined people worked for a better world.<br />

Professor Ian Lowe, President, <strong>Australian</strong> Conservation Foundation<br />

Taken from his Roundtable purpose speech<br />

7

INTRODUCTION<br />

The <strong>Kimberley</strong> <strong>Appropriate</strong> Economies<br />

Roundtable was held in Fitzroy Crossing,<br />

Western Australia on 11-13 October 2005.<br />

The Roundtable meeting was organised<br />

by the <strong>Kimberley</strong> Land Council (KLC),<br />

Environs <strong>Kimberley</strong> (EK), and the <strong>Australian</strong><br />

Conservation Foundation (ACF), all working<br />

together. The meeting looked at options,<br />

principles, and actions that promote appropriate<br />

and sustainable economic development in the<br />

Fitzroy Valley and Canning Basin, and in the<br />

wider <strong>Kimberley</strong> region.<br />

Over 100 people from the Fitzroy Valley and all<br />

across the <strong>Kimberley</strong>, and from other places in<br />

Australia and overseas, came to the Roundtable.<br />

They included traditional owners, pastoralists,<br />

training providers, small business people,<br />

farmers, university people, representatives of<br />

government agencies, and environmentalists.<br />

Interpreters were available to assist with<br />

communications.<br />

This short report (called an <strong>Interim</strong> <strong>Report</strong>)<br />

is the first one to come from the <strong>Kimberley</strong><br />

Roundtable. (A long report, called the Final<br />

<strong>Report</strong>, will be finished in March 2006, and<br />

will include everything that happened at the<br />

Roundtable.)<br />

This short report gives information about<br />

what happened at the Roundtable and what the<br />

outcomes were. It includes:<br />

• background information about the<br />

Roundtable and how it started<br />

• a summary of all the different sessions, and<br />

what came out of those sessions<br />

• a Statement of Principles put out by the<br />

people at the Roundtable<br />

• a summary of Key Actions that were<br />

developed<br />

• copies of many of the presentations that<br />

were given<br />

• a list of all the people who were there<br />

• a summary of what people thought were<br />

the good and not so good things about the<br />

Roundtable<br />

• photographs from the event<br />

• copies of the program and media reports<br />

The Final <strong>Report</strong> will be much longer than this<br />

report. It will cover all the information in this<br />

report, as well as details of the approach and<br />

methods used for putting on the Roundtable. It<br />

will include all of the presentations and workshop<br />

papers, and some background papers that were<br />

written to go alongside the Roundtable (even<br />

though they were not part of the Roundtable<br />

itself).<br />

Information on the <strong>Kimberley</strong> <strong>Appropriate</strong><br />

Economies Roundtable proceedings has also<br />

been put out through KLC and EK newsletters.<br />

Many of the presentations and papers are on<br />

the KLC website (http://www.klc.org.au/<br />

rndtable_docs.html).<br />

8

BACKGROUND<br />

TO THE ROUNDTABLE<br />

The idea for the Roundtable, and the way that it<br />

was pulled together, came from the <strong>Kimberley</strong><br />

community. There were many months of talks<br />

with community leaders and organisations<br />

in the <strong>Kimberley</strong> and elsewhere, and a lot of<br />

preparation by workers of the three organisations<br />

(<strong>Kimberley</strong> Land Council, Environs <strong>Kimberley</strong>,<br />

and <strong>Australian</strong> Conservation Foundation) to get<br />

funding, and to make all the arrangements for<br />

people to attend and give presentations.<br />

<strong>Kimberley</strong> people wanted to hold the Roundtable<br />

as a way of standing up for their rights and be<br />

in control of future development of the region.<br />

People were sick and tired of always responding<br />

to unsustainable development ideas put forward<br />

by people and industry groups who don’t even<br />

live in the <strong>Kimberley</strong>.<br />

<strong>Kimberley</strong> people have had to deal with many<br />

examples of this wrong way of thinking about<br />

<strong>Kimberley</strong> development. One idea was to grow<br />

cotton in the west <strong>Kimberley</strong>, using underground<br />

water taken from the Canning Basin to start with,<br />

and more water taken from the Fitzroy River later<br />

on. That would have meant building dams on the<br />

Fitzroy River, and clearing 225,000 hectares of<br />

land.<br />

Now there is study going on to look at taking<br />

water from the <strong>Kimberley</strong> and sending it to<br />

Perth.<br />

Many <strong>Kimberley</strong> people, both Indigenous and<br />

non-Indigenous, were very worried by these<br />

sorts of ideas. Local people looked to their<br />

organisations, like the <strong>Kimberley</strong> Land Council<br />

and Environs <strong>Kimberley</strong>, to help them push for<br />

a better way of doing things in the <strong>Kimberley</strong>:<br />

a way that would respect and look after people,<br />

culture, and the environment, but still allow<br />

<strong>Kimberley</strong> people to make a proper living from<br />

country.<br />

Environs <strong>Kimberley</strong> and <strong>Kimberley</strong> Land<br />

Council linked up with the <strong>Australian</strong><br />

Conservation Foundation to work together on<br />

ways to help <strong>Kimberley</strong> people have a strong<br />

voice in the development of the region. The<br />

three organisations made a strong bond with<br />

the community and each other, helping to start<br />

a campaign to protect the region from the wrong<br />

sort of development, and to look for ways to<br />

promote sustainable development.<br />

One way to promote sustainable development<br />

was to hold a big meeting of all the right people to<br />

talk about the future of the region. That meeting<br />

was called a Roundtable, where everyone could<br />

sit around together, as equals, to talk about the<br />

<strong>Kimberley</strong>’s future.<br />

Planning for the Roundtable started in October<br />

2004 with a planning day for a small group of<br />

people from the environmental and Indigenous<br />

agencies, key government agencies and regional<br />

organisations. This group talked about the<br />

purpose of the Roundtable, who should be<br />

included, and how it would be organised.<br />

A main part of this planning was to make sure<br />

that people who live and work in the <strong>Kimberley</strong><br />

were included: people like pastoralists and<br />

farmers, natural resource managers, traditional<br />

owners, tourism operators, art centre workers<br />

and artists, and those involved in conservation<br />

activities. A lot of time was spent gathering<br />

information from these people and others about<br />

9

appropriate development in the region. Many<br />

of these people were invited to come to the<br />

Roundtable to take part or give presentations.<br />

The involvement of key government agencies<br />

was seen to be important. Representatives<br />

from regional offices of the Department<br />

of Conservation and Land Management,<br />

Department of Indigenous Affairs and<br />

Department of Agriculture, as well as the<br />

<strong>Kimberley</strong> Development Commission and<br />

<strong>Kimberley</strong> College of TAFE, were invited<br />

to the Roundtable. The Premier of Western<br />

Australia, and the State Ministers for Regional<br />

Development and Conservation were also<br />

invited.<br />

Other people from outside the region who could<br />

make a useful contribution were invited to join in<br />

and present papers. These included researchers<br />

and scientists with experience in areas like<br />

economic development, governance structures,<br />

the natural ecology, and wetland research.<br />

A number of representatives from environmental<br />

groups and funding bodies were also invited<br />

to come to the Roundtable and to contribute<br />

papers to the final report.<br />

Three speakers from overseas were asked to<br />

speak about appropriate development ideas and<br />

opportunities in other parts of the world.<br />

OBJECTIVES<br />

OF THE ROUNDTABLE<br />

The purpose of the Roundtable was to develop<br />

a picture for ecologically, culturally, socially<br />

and economically sustainable development for<br />

the Fitzroy and Canning basins and the wider<br />

<strong>Kimberley</strong> region. This picture would be based<br />

on the vision and values of the region’s people.<br />

Other objectives were:<br />

• to re-affirm the values and vision of the<br />

people of the region<br />

• to provide opportunities for networking<br />

and information-sharing between people<br />

involved in a range of sustainable enterprises<br />

in the <strong>Kimberley</strong><br />

• to explore options and opportunities for<br />

appropriate development in the <strong>Kimberley</strong><br />

• to showcase examples of sustainable<br />

enterprises and initiatives in the <strong>Kimberley</strong><br />

and elsewhere.<br />

10

ROUNDTABLE<br />

FORMAT<br />

The Roundtable was held over two days, and<br />

each day included two main parts:<br />

• the big group sessions where everyone got<br />

together.<br />

• the smaller workshops sessions where<br />

people broke into groups.<br />

Day One<br />

The Roundtable started with a welcome to<br />

country by Gooniyandi elder Neville Sharp.<br />

The first big group session opened with a<br />

speech by Joe Ross, Bunuba Traditional Owner<br />

and Community Leader. That was followed by<br />

the keynote speech given by Wayne Bergmann,<br />

Nyikina man and <strong>Kimberley</strong> Land Council<br />

Executive Director.<br />

Then there were speeches by Pat Lowe from<br />

Environs <strong>Kimberley</strong>, Tom Birch, Chairman of<br />

the <strong>Kimberley</strong> Land Council, and Ian Lowe,<br />

President of the <strong>Australian</strong> Conservation<br />

Foundation. They talked about the purpose of<br />

the Roundtable.<br />

The next part of the Roundtable was another big<br />

group session, with presentations from scientists,<br />

Traditional Owners, and conservationists. These<br />

people talked about some research projects, and<br />

other things happening on country.<br />

After lunch, people broke off into small groups<br />

to hold workshops about six different topics:<br />

• Land Management<br />

• Art & Culture<br />

• Pastoralism<br />

• Agriculture<br />

• Tourism<br />

• Partnerships in Conservation<br />

People picked the workshop they wanted to<br />

go to. Each workshop included talks from<br />

<strong>Kimberley</strong> people about the things they were<br />

doing to look after the natural and cultural<br />

values of the region, at the same time as making<br />

a living from country and culture.<br />

After those presentations, people stayed in the<br />

small groups to talk about the things they thought<br />

were important for appropriate development in<br />

the <strong>Kimberley</strong>. They started to think about the<br />

‘key principles’ that should guide development,<br />

and to begin making up a ‘list of actions’ they<br />

thought would help appropriate development to<br />

happen.<br />

To end Day One, people came back to the big<br />

group to finish up.<br />

Day Two<br />

Day Two started with the second big group<br />

session. There were reports from each of the<br />

small groups that met on Day One.<br />

The big group then heard about some things that<br />

were happening overseas, with presentations by<br />

people from the World Conservation Union<br />

based in Switzerland, and from Vancouver in<br />

Canada.<br />

After that, people broke off into the same small<br />

group workshops again, to decide on the most<br />

important principles for development in the<br />

region, and to write down a list of actions that<br />

they would like to see happen.<br />

After lunch on the second day, everyone came<br />

back to the big group to hear about what people<br />

had said in the small group workshops. In the<br />

big group, people talked together about the<br />

main principles and the list of actions that they<br />

wanted to come out from the Roundtable. These<br />

were written down.<br />

To finish off, there were thank yous to everyone,<br />

and the Roundtable was closed by Traditional<br />

Owners.<br />

11

SUMMARY<br />

OF WHAT HAPPENED<br />

AT THE ROUNDTABLE<br />

This section gives an outline of what happened<br />

at the Roundtable. It mentions the speeches and<br />

presentations given by all the different people.<br />

A full copy of most of these presentations and<br />

speeches is included at the back of this report,<br />

after the page marked Appendix A.<br />

The big group sessions were aimed at giving<br />

information to people. The small group<br />

workshops were to let people have their say<br />

about things. These workshops were the main<br />

hard working part of the Roundtable.<br />

Day One<br />

First Big Group Session<br />

Opening speeches<br />

The Roundtable started with a welcome<br />

to country from Gooniyandi elder Neville<br />

Sharpe. Then Joe Ross, a Bunuba traditional<br />

owner and community leader, made an<br />

opening speech.<br />

Next, Wayne Bergmann, <strong>Kimberley</strong> Land<br />

Council Executive Director gave a keynote<br />

speech, to set the tone for the Roundtable.<br />

He was followed by Don Henry, the Director<br />

of the <strong>Australian</strong> Conservation Foundation,<br />

who thanked all the organisations and<br />

people that had provided funding and other<br />

assistance for the Roundtable.<br />

After that, presentations were made by<br />

representatives from the three Roundtable<br />

organisers - KLC Chairperson Tom Birch,<br />

ACF President Ian Lowe, and EK founding<br />

member and Secretary Pat Lowe. They<br />

all spoke about the partnership between<br />

their organisations, and the reasons for<br />

supporting the idea of the Roundtable.<br />

Presentations<br />

After a break for morning tea, people were<br />

given presentations on the work of three<br />

research projects being done by scientists<br />

and <strong>Kimberley</strong> people working together.<br />

Dr Andrew Storey from the University of<br />

WA gave an outline of the research findings<br />

that have been gathered on the natural and<br />

cultural values of the Fitzroy River area.<br />

That was followed by Ismahl Croft and Terry<br />

Murray, Walmajarri traditional owners, and<br />

Dr David Morgan from Murdoch University,<br />

who outlined the fish research projects<br />

being undertaken along the Fitzroy River<br />

and elsewhere in the <strong>Kimberley</strong>. In that<br />

research, traditional owners and scientists<br />

have been working closely together.<br />

Tanya Vernes, from World Wildlife Fund-<br />

Australia, and Desmond Hill, representing<br />

the Miriuwung Gajerrong people of the<br />

Ord Valley, joined Scott Goodson from the<br />

Department of the Environment, to look at<br />

the East <strong>Kimberley</strong>, especially the impact<br />

of agricultural development on the natural<br />

and cultural values of the Ord Valley. They<br />

finished by telling us about the partnerships<br />

that are being developed between the<br />

Aboriginal community and government<br />

agencies, working to restore and manage<br />

natural resources in the Ord Valley.<br />

12

Small Group Workshops<br />

Day One — Presentations and<br />

Discussions<br />

In the afternoon of Day One, people broke<br />

off into six workshop groups. The different<br />

workshops were about:<br />

• Land Management<br />

• Art & Culture<br />

• Pastoralism<br />

• Agriculture<br />

• Tourism<br />

• Partnerships in Conservation<br />

In each workshop group, three short<br />

presentations were made by <strong>Kimberley</strong> people<br />

working in activities aimed at looking after the<br />

cultural and natural values of the region.<br />

A brief summary of each workshop is given<br />

below.<br />

Land Management Workshop<br />

This workshop was looked after by Patrick<br />

Sullivan from AIATSIS, and included<br />

scientists, regional organisations, traditional<br />

owners, the Chair of the <strong>Kimberley</strong> Water<br />

Source Expert Panel, and a representative<br />

from the <strong>Australian</strong> Wildlife Conservancy at<br />

Mornington Station.<br />

• Will Philipiadis from the <strong>Kimberley</strong><br />

Regional Fire Management Project,<br />

gave an outline of the fire project’s plans<br />

to become a business providing land<br />

management services to landholders in<br />

the region, especially pastoralists.<br />

• Mervyn Mulardy Jnr spoke on a range<br />

of activities being developed by the<br />

Karajarri people south of Broome,<br />

including coastal management planning<br />

and landmark research into the<br />

commercialization of bush foods.<br />

• Anthony Watson and Hugh Wallace-<br />

Smith gave an outline of the range<br />

of activities being undertaken by the<br />

Yiriman Project with many Aboriginal<br />

communities and organisations.<br />

Tourism Workshop<br />

This workshop was looked after by Petrine<br />

McCrohan, a <strong>Kimberley</strong> TAFE tourism<br />

lecturer, and included representatives of<br />

traditional owner groups, overseas visitors,<br />

and other tour operators.<br />

Three Aboriginal tour operators made<br />

presentations on their experiences building<br />

and managing tourism enterprises.<br />

• Dillon Andrews, a Bunuba man, outlined<br />

the highs and lows of running tours in<br />

the Fitzroy Valley, and the establishment<br />

of a tour on his traditional country at<br />

Biridu.<br />

• Sam Lovell talked about establishing the<br />

first Aboriginal-owned and managed<br />

tourism enterprise in the <strong>Kimberley</strong>,<br />

which operated for eleven years.<br />

• Laurie Shaw, a Gooniyandi man, talked<br />

about the early stages he is going<br />

through in establishing his family<br />

tour on traditional country about 100<br />

kilometres east of Fitzroy Crossing.<br />

13

Pastoralism Workshop<br />

Danielle Eyre, the Sustainable Agriculture<br />

Facilitator for the <strong>Kimberley</strong> Natural<br />

Resource Management group, looked after<br />

this workshop, which included pastoralists,<br />

researchers and environmentalists.<br />

• Pastoralists Robyn Tredwell from<br />

Birdwood Downs and Alan ‘Doodie’<br />

Lawford from Bohemia Downs spoke<br />

about the types of diversification and<br />

sustainable land management practices<br />

that they have put in place on their<br />

lands.<br />

• Nadine Schiller from the Department<br />

of Agriculture gave an outline of<br />

the Integrated Natural and Cultural<br />

Resource Management Project,<br />

which is developing sustainable land<br />

management practices at Bow River<br />

Station and Violet Valley Reserve in the<br />

East <strong>Kimberley</strong>.<br />

Agriculture Workshop<br />

This workshop included people from the<br />

Department of Agriculture, the <strong>Kimberley</strong><br />

Water Source Expert Panel, a lawyer with<br />

expertise in water management regimes, and<br />

members of traditional owner groups. It was<br />

looked after by Ben Wurm from the KLC.<br />

• Tan Fowler spoke about the<br />

establishment and operations of her<br />

family’s organic farm at Twelve Mile,<br />

Broome.<br />

• Tanya Vernes, WWF, gave presentations<br />

on the impact of the Ord Scheme on the<br />

natural values of the area.<br />

• Des Hill talked about the impact of<br />

the Ord Scheme on the culture of the<br />

Miriuwung people.<br />

• Des Hill (Miriuwung Gajerrong<br />

Traditional Owner) and Scott Goodson<br />

(Department of Environment) spoke<br />

about the joint activities of traditional<br />

owners and government agencies in<br />

land management and conservation<br />

projects.<br />

Culture and Art Workshop<br />

• Participants in this workshop included<br />

coastal park managers, members of<br />

the <strong>Kimberley</strong> Aboriginal Law and<br />

Culture Centre committee, members<br />

of the Mangkaja Arts Resource Agency<br />

committee, the local broadcaster Radio<br />

Wangki, and representatives from the<br />

<strong>Kimberley</strong> Development Commission<br />

and a private Victorian funding<br />

foundation, as well as the director of<br />

an overseas capital trust fund. This<br />

workshop was looked after by Sarah Yu,<br />

a consultant anthropologist.<br />

• Miklo Corpus and Richard Hunter from<br />

Minyirr Park spoke about the ways that<br />

Yawuru people are working with others<br />

to keep culture strong and look after<br />

country along the Broome coastline.<br />

• Joe Brown spoke on behalf of the<br />

<strong>Kimberley</strong> Law and Culture Centre<br />

(KALACC).<br />

• Tommy May, Chairperson of Mangkaja<br />

Arts, spoke about the importance to<br />

Aboriginal people of protecting their<br />

intellectual property rights.<br />

Partnerships in Conservation Workshop<br />

This Workshop was looked after by Ari<br />

Gorring, former manager of the KLC Land +<br />

Sea Unit, and included a representative from<br />

an overseas conservation union, scientists,<br />

traditional owners and representatives from<br />

environmental organisations.<br />

• Max Haste, Department of Conservation<br />

and Land Management, spoke about<br />

building relationships and joint<br />

approaches to the management of<br />

conservation areas by the Department<br />

and traditional owner groups in the<br />

Fitzroy Valley.<br />

14

• Shirley Brown from Mulan community<br />

and Mark Ditcham, a KLC project<br />

officer, spoke about the establishment of<br />

the Paraku (Lake Gregory) Indigenous<br />

Protected Area (IPA).<br />

• Ismahl Croft, a Walmajarri man and<br />

KALACC/KLC project officer, and<br />

Joy Nuggett, a Walmajarri traditional<br />

owner, spoke about the development of<br />

the Great Sandy Desert IPA.<br />

Small Group Workshop Discussions<br />

After the workshop presentations, people<br />

stayed in the small groups to talk about<br />

appropriate development, and to identify<br />

the key principles for making sure that<br />

development is appropriate.<br />

People in the workshops were asked to think<br />

about what needs to happen for development<br />

to be appropriate in this region, and what are<br />

the reasons for the success and achievements<br />

or failures of particular enterprises and<br />

projects.<br />

The Day One workshop discussions were<br />

recorded and summarized. This information<br />

was used to develop the Roundtable’s<br />

Statement of Principles.<br />

Day Two<br />

Second Big Group Session<br />

To start off the second day, the big group listened<br />

to a summary of the things that were discussed in<br />

the small group workshops held on Day One.<br />

That was followed by presentations from the three<br />

overseas guest speakers. These presentations<br />

were about their experiences of appropriate<br />

development in other parts of the world.<br />

• Dr Grazia Borrini-Feyerabend, Vice Chair<br />

of the World Conservation Union’s (IUCN)<br />

Commission on Environmental, Economic<br />

and Social Policy (CEESP), gave a history<br />

of natural resource management and<br />

outlined recent key changes in international<br />

conservation policies. She then gave details<br />

of some conservation programs from<br />

overseas.<br />

• Ian Gill, President of Ecotrust Canada, spoke<br />

about the establishment and operations<br />

of Ecotrust, a fund set up to help people<br />

get financial backing for development<br />

projects that are appropriate to the natural<br />

environment.<br />

• Leah George-Wilson, Chief of Tsleil-<br />

Waututh First Nation, and a board member of<br />

Ecotrust Canada, described the experiences<br />

of the Tsleil-Waututh people, including the<br />

development of a partnership with Ecotrust<br />

Canada.<br />

After the tea break, people stayed in the big<br />

group, but talked with the other people at their<br />

tables. They were given a draft list of principles<br />

that had come from the Day One small group<br />

workshops. They were asked to work together<br />

to make comments about how these principles<br />

should be written down.<br />

The information collected from this session was<br />

used to develop the list of principles.<br />

Small Group Workshops for Day<br />

Two — Coming up with Actions and<br />

Principles<br />

In the afternoon of Day Two, people went back<br />

to those same small group workshops. They<br />

were asked to identify the most important things<br />

that should be done to carry the principles of<br />

appropriate development into action.<br />

These workshops came up with a summary of<br />

the key actions put forward in each of the six<br />

workshops.<br />

Last Big Group Session<br />

In the last big group session, people were asked<br />

to provide final comments and suggestions<br />

about the statement of principles and the list of<br />

15

actions to come out of the Roundtable. These<br />

comments, and all the earlier discussions, were<br />

used to come up with the outcomes listed later<br />

in this report.<br />

Closing statements were made by Miriuwung<br />

traditional owner Des Hill, Karajarri leader<br />

Mervyn Mulardy Junior, and Nyikina-Mangala<br />

leader Anthony Watson.<br />

Tom Birch (KLC Chairman), Don Henry and<br />

Rosemary Hill (ACF), and Craig Phillips (EK<br />

Chairman) thanked everybody for organising<br />

and being part of the Roundtable, and presented<br />

gifts to the overseas guests.<br />

The Roundtable was closed by Laurie Shaw<br />

and Neville Sharpe. People were invited to<br />

have a look at the Ngurrara Canvas, which was<br />

unrolled outside on the lawn. Artists and senior<br />

Aboriginal people gave an explanation of the<br />

painting.<br />

SIGNIFICANCE<br />

OF THE ROUNDTABLE<br />

This Roundtable was a very important event in<br />

planning for the development of the <strong>Kimberley</strong>.<br />

The forum was the first gathering of its kind<br />

in the region, bringing together a wide range<br />

of people, including many who are engaged<br />

in activities and enterprises that build up and<br />

look after the cultural and natural values of the<br />

region.<br />

The Roundtable came up with key principles for<br />

appropriate development in the Fitzroy Valley<br />

and the Canning Basin. These principles can be<br />

applied across the <strong>Kimberley</strong>.<br />

The Roundtable came up with some key actions<br />

that would help to make sure these principles<br />

were turned into strong and sustainable<br />

developments for the region.<br />

The Roundtable promoted the sharing of<br />

information and building of relationships and<br />

networks between all people and organisations.<br />

16

THE NEXT<br />

STEPS<br />

During the Roundtable itself, and in the<br />

evaluation survey that people filled in at the end<br />

of the conference, people said that there are too<br />

many meetings with lots of talking, but that is<br />

usually the end of it. People wanted to see some<br />

results coming from this Roundtable, in two<br />

main areas:<br />

• Clear reports and information made available<br />

to the people who were at the Roundtable,<br />

and to other interested people.<br />

• Steps taken to begin turning all the talk into<br />

real actions.<br />

The information from the Roundtable should<br />

be made available so that people can use it to<br />

start working on the actions. It was agreed that<br />

the Roundtable organizers would put out the<br />

following information and documents:<br />

• A ‘Statement of Principles’ developed from<br />

the workshops and the main sessions.<br />

• A ‘List of Actions’ developed from the<br />

workshops and the main sessions.<br />

• A short report on what happened at the<br />

Roundtable, and how the Principles and<br />

Actions were worked out. This was to be<br />

produced as quickly as possible.<br />

• A long report containing everything that<br />

happened at the Roundtable, including all<br />

the presentations and papers, to be produced<br />

within six months.<br />

• All the presentations and papers to be made<br />

be available on the internet at http://www.<br />

klc.org.au/rndtable_docs.html<br />

It was agreed that information and ideas from<br />

the Roundtable should be taken back to the<br />

community through visits and information<br />

sessions, and that a short DVD of the Roundtable<br />

would be made for community people. The<br />

organisers of the Roundtable agreed to look for<br />

funding to do these two tasks.<br />

People at the Roundtable also agreed that anyone<br />

could start moving forward with the ideas and<br />

actions developed at the Roundtable. It was<br />

decided that the organising partners could start<br />

moving forward with the priority actions, and<br />

that people themselves would decide what steps<br />

were appropriate to keep the initiative going.<br />

17

OUTCOMES<br />

There were two main Outcomes from the<br />

Roundtable:<br />

• A Statement of Principles<br />

• A List of Actions<br />

These were developed from the discussions in<br />

the small group workshops, and finished off at<br />

the last big group session. The organizers put<br />

all this information into a proper format after the<br />

Roundtable finished.<br />

STATEMENT OF PRINCIPLES<br />

People at the Roundtable felt that development<br />

of the <strong>Kimberley</strong> should be done carefully after<br />

a lot of thought. They felt that there should be<br />

a focus on what <strong>Kimberley</strong> people want, what<br />

would be suitable for the environment, and what<br />

would respect and care for people and culture.<br />

The Statement of Principles sets out what<br />

people thought should be the main ideas behind<br />

thinking about and planning development<br />

in the <strong>Kimberley</strong>. They said that appropriate<br />

development must be based on the following 11<br />

principles:<br />

1. The <strong>Kimberley</strong> region is a place of special<br />

cultural and environmental values with<br />

national and international significance.<br />

2. Culture guides economic activity for<br />

Indigenous people, and appropriate<br />

development must be based on healthy<br />

country and strong culture.<br />

3. Traditional Owners have the right to make<br />

decisions about their country, and that right<br />

must be respected.<br />

4. Aboriginal access to land and equity of<br />

land tenure are central to planning and<br />

development processes.<br />

5. Conservation and cultural management are<br />

valuable and important contributions to the<br />

economy and society. This contribution<br />

must be maintained by:<br />

• valuing and supporting local economies<br />

such as hunting, fishing, and looking<br />

after people, culture and country<br />

• incorporating the rights of Traditional<br />

Owners when conservation areas are<br />

established<br />

• supporting senior Indigenous people<br />

in the transmission of knowledge and<br />

confidence to young people<br />

• ensuring return of benefits from<br />

cultural information to the holders of<br />

that information.<br />

6. The region’s people have the right to take<br />

part in planning for the region and to have<br />

their views respected and included, and<br />

this right must be practically supported by<br />

Government.<br />

7. The Fitzroy River, ground waters, and<br />

conservation areas are valuable natural<br />

resources requiring protection through an<br />

appropriate legal framework.<br />

8. Economic initiatives based on a range<br />

of different sustainable enterprises best<br />

support the needs and wishes of <strong>Kimberley</strong><br />

people, and these must be developed,<br />

promoted, and actively supported.<br />

9. Traditional and contemporary skills<br />

and knowledge are valuable assets, and<br />

enterprise planning and management<br />

tailored to local needs will assist in the<br />

transfer of these assets.<br />

10. Region-wide co-operative networks will<br />

assist and support both successful and new<br />

local enterprises.<br />

18

11. Support for appropriate development<br />

initiatives through sufficient and ongoing<br />

funding is essential.<br />

KEY ACTIONS<br />

The Roundtable developed a range of Key<br />

Actions that would help people move forward<br />

with their ideas for sustainable and appropriate<br />

development in the <strong>Kimberley</strong>. These actions<br />

form a guiding structure, and people at the<br />

Roundtable understood that there are many more<br />

concrete actions that they as individuals, and that<br />

their organisations and agencies, can do.<br />

The Key Actions from the Roundtable were<br />

worked out mostly in the small group workshops,<br />

then finished off in the big group session. Each<br />

Workshop came up with its own actions. Some<br />

of the key points from these workshops are given<br />

below.<br />

Discussion of Key Actions in the Small<br />

Group Workshops<br />

Land Management Workshops<br />

People talked about the importance of<br />

working together and developing networks<br />

and partnerships, and for resources to be<br />

put together from a number of sources,<br />

with greater co-operation between land<br />

management projects. They discussed the<br />

importance of trusting Aboriginal people<br />

to manage their own affairs.<br />

Research should be undertaken into the<br />

options for development for <strong>Kimberley</strong><br />

Aboriginal people, and pilot projects that<br />

look at new ideas should be supported.<br />

Access agreements on pastoral lands and<br />

the development of mixed land use and<br />

ownership models should be supported and<br />

promoted.<br />

Tourism Workshops<br />

Participants discussed concerns about<br />

finance and capital, including ways to make<br />

it easier to get assistance for Aboriginal<br />

people starting or operating cultural<br />

and eco-tourism businesses. A properly<br />

resourced body should be set up to provide<br />

clear information and advice to people on<br />

things like ways to get funding, money for<br />

development, and good business advice.<br />

The rights of Aboriginal people to control,<br />

use and access their traditional country<br />

were important issues. People said that<br />

these rights and interests must be fully<br />

recognised in legislation and through comanagement<br />

arrangements in conservation<br />

areas and other forms of agreement with<br />

government, miners and pastoralists.<br />

Organisations like KLC, EK and ACF<br />

should continue to support the rights<br />

of traditional owners to be involved in<br />

decision-making about the management<br />

and maintenance of traditional country.<br />

Indigenous tour operators in the Fitzroy<br />

Valley could form a steering committee to<br />

promote co-operation and support, and to<br />

push their interests forward. They could<br />

develop strategies for the future, including<br />

a system of accreditation for tour operators<br />

in the Fitzroy Valley.<br />

Non-Aboriginal tour operators need to<br />

be informed and educated about cultural<br />

protocols and rules through interpretation<br />

and other workshops with traditional<br />

owners.<br />

Passing on traditional and cultural<br />

knowledge to younger generations is very<br />

important, along with training for younger<br />

people to learn about their heritage and<br />

about developing guiding skills.<br />

Agriculture Workshops<br />

People talked about developing a Statement<br />

of Guidelines for sustainable agriculture<br />

19

in the <strong>Kimberley</strong> with rules based on<br />

community priorities. The Guidelines<br />

should stick to the State Sustainability<br />

Strategy. A public commitment to the<br />

Guidelines from the State Government is<br />

needed.<br />

A survey of local community interest in<br />

sustainable agriculture could be carried out,<br />

and might include an investigation of the<br />

recently announced State NOTPA program.<br />

Co-operatives to provide support for<br />

local communities engaged in sustainable<br />

agriculture were also important.<br />

Future sustainable agriculture in<br />

the <strong>Kimberley</strong> should be integrated<br />

with successful, existing community<br />

development and land management<br />

programs like the <strong>Kimberley</strong> Regional Fire<br />

Management Fire Project or the Yiriman<br />

project.<br />

A coordinated research approach driven by<br />

communities was recommended.<br />

Pastoralism Workshops<br />

Traditional rights of ownership must be<br />

recognised, and people were worried about<br />

the time taken to transfer the control of title<br />

of traditional country from the ILC and<br />

other bodies that hold lands for Aboriginal<br />

people. These agencies need to be clear in<br />

negotiating the transfer of leases so that<br />

traditional owners can gain control sooner.<br />

The WA Department of Land Information<br />

(and the Pastoral Lands Board) should<br />

reform land tenure arrangements to reflect<br />

the diversity and range of activities, people,<br />

resources and governance structures on<br />

pastoral leases across the region and the<br />

State.<br />

Cultural information could benefit the<br />

people who own it, but benefits must<br />

go to the appropriate people. All levels<br />

of government must recognise that<br />

cultural information and knowledge is<br />

the intellectual property of the traditional<br />

owners.<br />

In fitting pastoral management systems<br />

to local ecological systems, approaches to<br />

fire management should be based on local,<br />

on-ground teams. The KLC and other<br />

organisations should push strongly for this<br />

to happen.<br />

Skills and knowledge can be developed<br />

through training that is clear, that teaches<br />

good skills that can be used anywhere,<br />

and that is right for the region. The Cooperative<br />

Research Centres and other<br />

research bodies should go into longer-term<br />

partnerships with traditional owners, to<br />

carry out projects and to share results.<br />

The role of senior Aboriginal people in the<br />

transmission of knowledge and confidence<br />

to young people is critical. The right<br />

agencies and organisations must promote<br />

local schooling and other educational<br />

opportunities, so that younger people have<br />

closer contact with older people.<br />

Art and Culture Workshops<br />

Aboriginal artists and cultural people need<br />

to have access to their country, and to have<br />

their rights as traditional owners recognised.<br />

Access agreements must be negotiated with<br />

pastoralists, and a permissions process<br />

should be set up so that people can go onto<br />

country for cultural activities.<br />

Cultural enterprise activities must be<br />

supported and combined with other<br />

activities such as cultural tourism, so that<br />

people are able to earn money from cultural<br />

work.<br />

Respect for land and culture must be built<br />

20

up, and a range of educational activities<br />

should be developed and supported. These<br />

include language, song and dance, and<br />

cross-cultural training programs. The use<br />

and promotion of a cultural map of the<br />

Fitzroy River and surrounding country is<br />

important to these ideas.<br />

The passing down of culture from senior<br />

people to kids is very important, and<br />

young people must be supported to go out<br />

on country as much as possible through<br />

activities such as holiday culture camps.<br />

Painting programs for youth should be<br />

developed.<br />

Partnerships in Conservation Workshops<br />

Conservation management arrangements<br />

should include some lands being registered<br />

as conservation agreement areas under<br />

the CALM Act. Community Conservation<br />

Areas would be a good way to protect<br />

country and culture.<br />

Government funding for conservation<br />

projects is a major problem. The big<br />

number of programs should be joined into<br />

one main ‘Caring for Country’ program.<br />

Conservation funding should be long term,<br />

be regionally-controlled, and be available<br />

across a range of land tenures. Projects<br />

could be Australia-wide.<br />

Problems in accessing funding come from<br />

complicated and confusing application<br />

processes. These processes should be<br />

simplified, and more support should<br />

be provided to applicants to develop<br />

submissions.<br />

Key organisations should lobby for strong,<br />

long-term support for conservation and<br />

cultural maintenance activities. Inclusive<br />

planning should be given a high priority in<br />

the region.<br />

It is important for community-based<br />

projects such as Fire Teams to visit other<br />

groups, exchange information, and see<br />

what others are achieving.<br />

The engagement of youth in conservation<br />

activities is a priority. Education and<br />

training on country is the main way of<br />

getting young people interested in caring<br />

for country and other land management<br />

activities. The contribution and work of<br />

elders, and the need for them to be paid<br />

properly, was recognised.<br />

It was recommended that land and language<br />

cultural programs become a major part of<br />

the education system.<br />

To make the most of visual learning, and<br />

young people’s interests in computer<br />

technology, conservation activities should<br />

include skills development and training<br />

in computer technologies like Global<br />

Information Systems and media editing.<br />

The promotion of business management<br />

mentoring by successful local business<br />

people is important.<br />

Summary of Key Actions<br />

For this report, the key points from the<br />

workshops have been made wider to cover all of<br />

the different types of development in the region.<br />

Even though they are grouped under headings,<br />

many of these actions could be applied to a<br />

number of different enterprises.<br />

Guidelines for Sustainable Development<br />

Action 1 Develop an enforceable Statement<br />

of Guidelines for sustainable dev–<br />

elopment in the <strong>Kimberley</strong><br />

People at the Roundtable felt<br />

that there should be a set of rules<br />

written up so that they can look at<br />

any ideas for development, and see<br />

if the idea is sustainable, good for<br />

21

Research<br />

Action 2<br />

Action 3<br />

the region and its people, and fits<br />

the Statement of Principles.<br />

These guidelines would be<br />

developed with the priorities set<br />

by communities for development<br />

in their area. They would closely<br />

follow the State Sustainability<br />

Strategy. The State Government<br />

would be asked to publicly commit<br />

to the Guidelines (possibly through<br />

a framework agreement).<br />

Develop a long term, integrated, and<br />

co-operative research program that<br />

includes providing research results<br />

to the <strong>Kimberley</strong> community.<br />

People at the Roundtable felt that<br />

research in the region should<br />

focus on the big picture and the<br />

long-term, and should involve<br />

local people at all levels, including<br />

research planning and reporting.<br />

Research should be driven by the<br />

communities in the region, and<br />

respond to their needs.<br />

Research projects should be done<br />

in partnership with local people or<br />

organisations wherever possible.<br />

Results should be available to<br />

everyone, and local people should<br />

have control over the information<br />

they provide for research. Cooperative<br />

Research Centres<br />

(CRC’s) could play a big role in<br />

research.<br />

Conduct a survey of local community<br />

interest in sustainable agriculture or<br />

other development.<br />

People at the Roundtable thought<br />

that local communities should<br />

be asked if they are interested in<br />

developing sustainable enterprises,<br />

including agriculture. Their<br />

ideas would help in planning<br />

for infrastructure and support.<br />

The State Government’s New<br />

Opportunities for Tropical Pastoralism<br />

and Agriculture (NOTPA)<br />

program could provide a basis for<br />

this research.<br />

Support and Integration<br />

Action 4 Establish systems and structures<br />

to promote, assist and support<br />

new and existing sustainable and<br />

appropriate enterprises.<br />

People at the Roundtable thought it<br />

would be useful to develop ways for<br />

local people to support each other<br />

in their businesses and enterprises.<br />

There were many ideas about how<br />

this could work.<br />

Communities engaged in<br />

sustainable agriculture could start<br />

up co-operatives to help sell their<br />

products and to provide information<br />

and support.<br />

New ideas and projects could be<br />

lined up with successful community<br />

development programs<br />

that are already up and running, so<br />

that people can share information<br />

and work side by side. Successful<br />

business people could be<br />

encouraged and supported to<br />

help others set up and run their<br />

businesses.<br />

People or organisations could work<br />

together in a coordinated research<br />

approach, driven by communities,<br />

that would benefit everyone.<br />

Tour operators from the Fitzroy<br />

Valley could form a steering<br />

committee to make decisions and<br />

recommendations about tourism<br />

22

development, and to help people<br />

get new projects off the ground.<br />

Resources from a number of places<br />

could be combined. This would<br />

increase co-operation among projects,<br />

help show the need for local<br />

and regional networking, and allow<br />

for good planning and management<br />

of new areas of enterprise.<br />

All of these things would put trust<br />

in the capacity of people to manage<br />

their own affairs.<br />

Conservation Areas<br />

Action 5 Develop processes that promote<br />

and support culturally appropriate<br />

conservation areas.<br />

People at the Roundtable felt that it<br />

would be good to see if some land<br />

can be registered as conservation<br />

agreement areas under the CALM<br />

Act. This would allow people to try<br />

for funding to help with new and<br />

cultural enterprises.<br />

Key groups could be established to<br />

promote strong, long term support<br />

for conservation and environmental<br />

and cultural maintenance.<br />

Planning<br />

Action 6<br />

Investigate, develop, and implement<br />

planning processes that include<br />

<strong>Kimberley</strong> people as the main<br />

stakeholders and decision makers.<br />

People placed a high priority on<br />

planning for the <strong>Kimberley</strong> region,<br />

and were strong about making sure<br />

local people were included at all<br />

levels of planning.<br />

On the Ground Initiatives and Activities<br />

Action 7 Promote and support on ground<br />

initiatives managed and operated<br />

by local people.<br />

People at the Roundtable felt that it<br />

was important to the whole region<br />

to know about, assist, promote,<br />

and support on ground initiatives<br />

that are already operating. People<br />

running successful projects could<br />

visit other groups to share information,<br />

learn about new ideas, and<br />

see what others are achieving. This<br />

would help to develop confidence<br />

and pride in these valuable<br />

initiatives, provide a kick start for<br />

pilot projects, and show good examples<br />

to people starting up new<br />

projects.<br />

<strong>Kimberley</strong> people and organisations<br />

could push for changes to some on<br />

the ground projects to make sure<br />

that they are managed and operated<br />

by local people, and that the work is<br />