Positive Behavior Support for ALL Michigan ... - Oakland Schools

Positive Behavior Support for ALL Michigan ... - Oakland Schools

Positive Behavior Support for ALL Michigan ... - Oakland Schools

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

MDE<br />

<strong>Michigan</strong> Department of Education<br />

Office of Special Education and<br />

Early Intervention Services<br />

<strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong><br />

<strong>for</strong><br />

<strong>ALL</strong> <strong>Michigan</strong> Students:<br />

Creating Environments<br />

That Assure Learning<br />

February 2000<br />

IDEA State Improvement Plan (SIP)<br />

00-1a

For hard copies of this document:<br />

Awareness and Dissemination (Hub 2 of the SIP)<br />

Eaton Intermediate School District<br />

1790 East Packard Highway<br />

Charlotte, <strong>Michigan</strong> 48813<br />

(800) 593-9146 #3<br />

Email: mhewer@eaton.k12.mi.us<br />

For electronic copies of this document:<br />

Visit the SIP web site at:<br />

http://www.michigansipsig.match.org<br />

State Board of Education<br />

Dorothy Beardmore, President<br />

Kathleen N. Straus, Vice-president<br />

Herbert S. Moyer, Secretary<br />

Sharon A. Wise, Treasurer<br />

Sharon L. Gire, NASBE Delegate<br />

Marianne Yared McGuire, Board Member<br />

Michael David Warren, Jr., Board Member<br />

Eileen Weiser, Board Member<br />

Ex Officio Members<br />

John Engler, Governor<br />

Arthur E. Ellis, Superintendent of Public Instruction<br />

This document was produced through an IDEA State Improvement Grant awarded by the <strong>Michigan</strong> Department of Education.<br />

The opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the <strong>Michigan</strong> State Board of<br />

Education or the U.S. Department of Education, and no endorsement is inferred. This document is in the public domain<br />

and may be copied <strong>for</strong> further distribution when proper credit is given. For further in<strong>for</strong>mation or inquiries about this<br />

project, contact Judy M. Hazelo at the Office of Special Education and Early Intervention Services; P.O. Box 30008; Lansing,<br />

<strong>Michigan</strong> 48909.<br />

00-1a

MDE<br />

<strong>Michigan</strong> Department of Education<br />

Office of Special Education and<br />

Early Intervention Services<br />

<strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong><br />

<strong>for</strong><br />

<strong>ALL</strong> <strong>Michigan</strong> Students:<br />

Creating Environments<br />

That Assure Learning<br />

February 2000<br />

IDEA State Improvement Plan (SIP)<br />

00-1a

<strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>ALL</strong> <strong>Michigan</strong> Students:<br />

Creating Environments That Assure Learning<br />

Dedication<br />

We dedicate this work to <strong>ALL</strong> kids!<br />

Acknowledgments<br />

We appreciate the leadership of the State Board of Education and Dr. Jacquelyn<br />

Thompson, Director of the Office of Special Education and Early Intervention<br />

Services, in recognizing the importance of getting this in<strong>for</strong>mation into the<br />

hands of <strong>Michigan</strong> parents and practitioners. This tool enables and teaches<br />

parents and practitioners to better meet the learning needs of <strong>ALL</strong> <strong>Michigan</strong><br />

students. We thank the people who took the time to review the contents of this<br />

document. Their input was invaluable in making this document a practical and<br />

usable resource. We would also like to thank Emily Gustavson, graphic artist,<br />

Margot Landa Kielhorn, editor, and Denise Smith, desktop publisher, <strong>for</strong> their<br />

work on this document.<br />

Core Work Group<br />

Kathy Clegg, Lapeer Intermediate School District<br />

John Dickey, Ph.D., <strong>Michigan</strong> Department of Education, Office of Special<br />

Education and Early Intervention Services<br />

Tricia Luker, Epilepsy Foundation of <strong>Michigan</strong><br />

Frances Mueller, Ph.D., <strong>Michigan</strong> Federated Chapters of the Council <strong>for</strong> Exceptional<br />

Children, <strong>Oakland</strong> <strong>Schools</strong><br />

Jim Paris, <strong>Michigan</strong> Department of Education, Office of Special Education and<br />

Early Intervention Services<br />

Sue Pratt, Citizens Alliance to Uphold Special Education<br />

Deborah Roush, Ed.S., Children with Attention Deficit Disorder<br />

Bernie Travnikar, Ed.D., Consultant, <strong>Michigan</strong> <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong><br />

Initiative, <strong>Michigan</strong> Department of Education State Improvement Grant<br />

Claudia Williamson, <strong>Michigan</strong> Association of School Social Workers, Flat Rock<br />

Community <strong>Schools</strong><br />

Reviewers<br />

Introduction – 1

Reviewers<br />

Kathy Al-Rubaiy, Superintendent, Livingston Educational Service Agency<br />

Penny Axe, Director of Special Education, Wayland Public <strong>Schools</strong><br />

Kristal Ehrhardt, Graduate Student, Western <strong>Michigan</strong> University<br />

Meme Hieneman, Director of the Department of Child and Family Studies,<br />

Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, University of South Florida<br />

Joanne Hopper, Curriculum Coordinator, Lapeer Intermediate School District<br />

Lucy Hough-Waite, Assistant Director of Special Education, Kent Intermediate<br />

School District<br />

Jack Martin, Wayne-Westland Community <strong>Schools</strong>, <strong>Michigan</strong> Association of<br />

School Psychologists<br />

Valerie Mierzwa, Teacher Consultant, <strong>Michigan</strong> Federated Chapters of the Council<br />

<strong>for</strong> Exceptional Children, <strong>Michigan</strong> Council <strong>for</strong> Children with <strong>Behavior</strong>al Disorders,<br />

Farmington Public <strong>Schools</strong><br />

Gigi Mitchell, Director of Student <strong>Support</strong> Services, <strong>Oakland</strong> <strong>Schools</strong><br />

Donna Secor, <strong>Michigan</strong> Association of School Social Workers, Forest Hills Public<br />

<strong>Schools</strong><br />

Deneen Sink, Parent, Livonia <strong>Schools</strong><br />

Ken Smith, Parent, Children with Attention Deficit Disorder<br />

Greg Waller, Supervisor of Special Education, Traverse Bay Area Intermediate<br />

School District<br />

Introduction – 2

Introduction<br />

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), as amended in 1997,<br />

reflects a revolution in the theory and practice of behavior intervention. Students<br />

who experience both disability and behavioral challenges must now<br />

receive positive behavior support developed upon a foundation of functional<br />

assessment. However, the law does not define the procedures <strong>for</strong> positive behavior<br />

support. This document has been developed to address this need, af<strong>for</strong>ding<br />

parents and practitioners the basic in<strong>for</strong>mation needed <strong>for</strong> good faith implementation<br />

of such procedures.<br />

While the IDEA serves as the catalyst <strong>for</strong> this initiative, positive behavior support<br />

is appropriate <strong>for</strong> <strong>ALL</strong> students who present behavior challenges. The<br />

entire educational community benefits when <strong>ALL</strong> students learn how to pursue<br />

their own legitimate needs and interests without compromising the rights and<br />

privileges of others.<br />

The professional literature affirms the systematic practice of positive behavior<br />

support on a schoolwide basis. In addition to helping learning environments<br />

become safer and more productive, this approach offers the potential of improving<br />

the quality of life of everyone engaged in the teaching and learning<br />

process.<br />

We anticipate the ongoing development of additional products to assist schools,<br />

families, and communities in supporting positive results <strong>for</strong> <strong>ALL</strong> students. This<br />

document is just a beginning. We hope it will prove to be a valuable resource in<br />

the pursuit of our goals <strong>for</strong> improved student achievement in our schools.<br />

Jacquelyn J. Thompson, Ph.D., Director<br />

Office of Special Education and<br />

Early Intervention Services<br />

<strong>Michigan</strong> Department of Education<br />

Introduction – 3

Introduction – 4

Preface<br />

All contributors to the document <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>ALL</strong> <strong>Michigan</strong><br />

Students: Creating Environments That Assure Learning are firm in their conviction<br />

that the door to a meaningful education must not be closed to any student<br />

who could, with our help, pass through. Students who persistently exhibit<br />

inappropriate behavior limit their learning opportunities and compromise<br />

teaching and the learning of others. It is no longer acceptable to continue with<br />

the status quo approach to problem behavior. It is time to systematically address<br />

challenging behaviors in a comprehensive, research-validated, humane manner.<br />

<strong>Michigan</strong> needs schools in which <strong>ALL</strong> students are taught how to act within<br />

accepted norms. Effective schools are safe and orderly. <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong><br />

(PBS)—with its Functional Assessment of <strong>Behavior</strong> and <strong>Behavior</strong> Intervention<br />

Plan components—provides a way <strong>for</strong> us to commit our talent and our<br />

resources to making our schools safe. We must be unequivocal in our resolve to<br />

teach students how to pursue their own needs and interests legitimately, without<br />

compromising the rights and privileges of others. Society expects this, and<br />

our students deserve nothing less.<br />

In pursuit of these goals, a representative group of professionals, advocates,<br />

administrators, and parents first met in the fall of 1998 with the intent of producing<br />

a document to explain the conceptual framework and practical implementation<br />

of PBS, the umbrella framework that covers multiple types of interventions.<br />

As this core team wrestled with the known in<strong>for</strong>mation about PBS, it became<br />

clear that implementing PBS in isolation is insufficient, and that PBS includes a<br />

range of best and promising practices that exceeded the personal philosophies of<br />

individual core team members. Collaborating on this document expanded the<br />

core team members’ knowledge of best practice, rekindling their passion <strong>for</strong> the<br />

concept of PBS. This initial document is offered to the field in the hope that<br />

readers will be similarly inspired to learn about and implement PBS in our<br />

schools to enhance learning and improve the quality of life <strong>for</strong> students, their<br />

families, school personnel, and service providers throughout the state.<br />

Adults in the state of <strong>Michigan</strong> who face complex situations need access to comprehensive<br />

PBS support and resources to successfully teach students new ways of<br />

behaving. It is our intent to initiate ongoing conversation about what really matters<br />

in the lives of our students. It is our hope that people who really care about <strong>ALL</strong> kids<br />

will join this conversation and extend the dialogue. The Reader Response <strong>for</strong>m in<br />

Section 14 provides one way <strong>for</strong> you to enter into the conversation.<br />

Proposed changes in perspective and practice articulated in this document are<br />

offered in the sincere belief that traditional methods have failed to address<br />

ongoing challenging student behaviors. The new philosophy and promising<br />

practices of <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> are offered here in the belief that <strong>ALL</strong><br />

students are worth the ef<strong>for</strong>t.<br />

Introduction – 5

Introduction – 6

Table of Contents<br />

Section 1 – Exploring Beliefs and Defining <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong><br />

• What Is <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong>? 1-1<br />

• <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong>: The Concept 1-1<br />

• Why Use <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong>? 1-2<br />

• When Should <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> Be Implemented? 1-2<br />

• What Does This Document Provide? 1-3<br />

• Purpose of This Document 1-3<br />

• <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> Implementation Plan 1-3<br />

• Anticipated Outcomes <strong>for</strong> <strong>Michigan</strong> Students 1-3<br />

• Anticipated Benefits 1-4<br />

Section 2 – Assessing the Status of <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong><br />

in Your District<br />

• Getting Started with <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> 2-1<br />

• What Does Not Work? 2-1<br />

• What Does Work? 2-1<br />

• What Is the Foundation of <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong>? 2-2<br />

• What Are the Features of the <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> Approach? 2-2<br />

• What Types of Problems Does <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> Address? 2-3<br />

• What Outcomes Are Emphasized Using <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong>? 2-3<br />

• What Does a Schoolwide <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> System Look Like? 2-3<br />

• Where to Start? 2-4<br />

• When to Start? 2-4<br />

• <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> Works! 2-5<br />

• Randy’s Story: A Social Worker’s Perceptions regarding <strong>Positive</strong><br />

<strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> 2-8<br />

• The Nature of the Approach 2-10<br />

Section 3 – Building a Model <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> Team<br />

• Introduction 3-1<br />

• Student <strong>Support</strong> Teams 3-2<br />

• Student <strong>Support</strong> Teams: Basic Considerations 3-2<br />

• Student <strong>Support</strong> Teams: Structure and Size 3-3<br />

• Core Team 3-4<br />

• Auxiliary Team (Expanded Team) 3-4<br />

• Selection of Team Members 3-4<br />

• Duration of Team Membership 3-4<br />

• Student <strong>Support</strong> Team Meetings 3-4<br />

• Incentives <strong>for</strong> Membership 3-5<br />

• Personnel Development 3-5<br />

Introduction – 7

Section 4 – Completing a Functional Assessment of <strong>Behavior</strong><br />

• What Is Functional Assessment of <strong>Behavior</strong>? 4-1<br />

• Basic Beliefs <strong>Support</strong>ing Functional Assessment of <strong>Behavior</strong> 4-1<br />

• Four Main Goals of Functional Assessment of <strong>Behavior</strong> 4-2<br />

• Two Major Techniques <strong>for</strong> Obtaining In<strong>for</strong>mation <strong>for</strong><br />

Functional Assessment of <strong>Behavior</strong> 4-2<br />

• Three Values of Functional Assessment of <strong>Behavior</strong> 4-2<br />

• When Is Functional Assessment of <strong>Behavior</strong> Necessary? 4-2<br />

• Functional Assessment of Academic and <strong>Behavior</strong> Challenges<br />

Process Checklist 4-6<br />

Section 5 – Collaborating on a <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> Intervention Plan<br />

• What Is a <strong>Behavior</strong> Intervention Plan? 5-1<br />

• Components of a <strong>Behavior</strong> Intervention Plan 5-2<br />

• <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> in the Classroom: Basic Assumptions <strong>for</strong><br />

Writing a <strong>Behavior</strong> Intervention Plan 5-4<br />

Section 6 – Linking <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> to Special Education<br />

• How Can <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> Aid the<br />

Prereferral-to-Special Education Evaluation Process? 6-1<br />

• Prereferral and Referral Processes 6-2<br />

• Special Education Evaluation and Eligibility 6-3<br />

• What Is an Individualized Education Program? 6-4<br />

• How Can a Functional Assessment of <strong>Behavior</strong> and <strong>Behavior</strong><br />

Intervention Plan Help Guide the Individualized Education<br />

Program Team? 6-5<br />

• How Can a Functional Assessment of <strong>Behavior</strong> and/or<br />

<strong>Behavior</strong> Intervention Plan Be Addressed in an Individualized<br />

Education Program? 6-6<br />

• The Required Use of Functional Assessment of <strong>Behavior</strong> and<br />

<strong>Behavior</strong> Intervention Plans When Students with Disabilities<br />

Are Removed from School 6-8<br />

• What Constitutes a Functional Assessment of <strong>Behavior</strong> and<br />

<strong>Behavior</strong> Intervention Plan? 6-9<br />

• Manifestation Determination Review 6-10<br />

• When Are Functional Assessment of <strong>Behavior</strong>, <strong>Behavior</strong><br />

Intervention Plans, and Manifestation Determination Reviews Required? 6-11<br />

• General Change of Placement 6-12<br />

• Change of Placement: Drugs and Dangerous Weapons 6-12<br />

• Change of Placement: Other Dangerous Situations 6-13<br />

Section 7 – Designing <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> Strategies<br />

• Conditions Related to Curriculum and Instruction 7-1<br />

• Preventive and Early Intervention Strategies 7-2<br />

Introduction – 8

• Conditions Related to Physical and Mental Health Disorders 7-3<br />

• Consideration of Maintenance over Time and Generalization<br />

across Settings 7-4<br />

• What about General Education Students? 7-4<br />

• What about Students with Section 504 Plans? 7-5<br />

• What about Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Students? 7-6<br />

Section 8 – Responding to Emergency Situations:<br />

When Students Are Physically Dangerous<br />

• Staff Training 8-1<br />

• Corporal Punishment Prohibited 8-2<br />

• School Response to Violence in <strong>Michigan</strong> 8-2<br />

• Best Practice Considerations 8-3<br />

Section 9 – Conclusion 9-1<br />

Section 10 – Resources<br />

• Early Warning, Timely Response 10-1<br />

• “Effective <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong>: A Systems Approach to Proactive<br />

Schoolwide Management” 10-1<br />

• Functional <strong>Behavior</strong> Assessment: An Annotated Bibliography 10-1<br />

• Journal of <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> Interventions 10-1<br />

• <strong>Michigan</strong> <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> Initiative 10-2<br />

• Research Connections in Special Education 10-2<br />

• School-Community Partnerships – A Guide, Conduct and<br />

<strong>Behavior</strong> Problems: Intervention and Resources <strong>for</strong> School<br />

Aged Youth, Sampler on Resiliency and Protective Factors 10-2<br />

• State Documents<br />

Alabama 10-2<br />

Cali<strong>for</strong>nia 10-3<br />

Kansas 10-3<br />

Minnesota 10-3<br />

Utah 10-3<br />

Vermont 10-4<br />

West Virginia 10-4<br />

• The Agreement of Collaboration <strong>for</strong> <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> 10-4<br />

• The Exemplary Mental Health Programs: School Psychologists<br />

As Mental Health Service Providers 10-4<br />

• Teaching Exceptional Children 10-4<br />

• Commercially Available Resources:<br />

Aggression Replacement Training: A Comprehensive Intervention<br />

<strong>for</strong> Aggressive Youth 10-5<br />

Analysis of Sensory <strong>Behavior</strong> Inventory-Revised 10-5<br />

Anger Management <strong>for</strong> Youth: Stemming Aggression and Violence 10-5<br />

Introduction – 9

Basic Skill Builders: A Precision Teaching Approach 10-5<br />

BEST Practices, <strong>Behavior</strong>al and Educational Strategies <strong>for</strong> Teachers 10-6<br />

Conflict in the Classroom, The Education of At-Risk and<br />

Troubled Students 10-6<br />

Functional Assessment and Intervention Program 10-6<br />

Homework Partners: Practical Strategies <strong>for</strong> Parents and Teachers 10-6<br />

Life Space Intervention: Talking with Children and Youth in Crisis 10-7<br />

Nonviolent Crisis Intervention 10-7<br />

Reaching the Hard to Teach: Participant Packet 10-7<br />

Skillstreaming in Early Childhood: Teaching Prosocial Skills<br />

to the Preschool and Kindergarten Child, Skillstreaming in the<br />

Elementary School Child: A Guide <strong>for</strong> Teaching Prosocial Skills,<br />

Skillstreaming the Adolescent: A Structured Learning Approach<br />

to Teaching Prosocial Skills 10-7<br />

Techniques <strong>for</strong> Managing Verbally and Physically Aggressive Students 10-8<br />

The Administrator’s Desk Reference of <strong>Behavior</strong> Management 10-8<br />

The High Five Program: A <strong>Positive</strong> Approach to School Discipline 10-8<br />

The Motivation Assessment Scale 10-8<br />

The Prepare Curriculum: Teaching Prosocial Competencies 10-9<br />

The Rehabilitation Research and Training Center (RRTC) on<br />

<strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> 10-9<br />

The Tough Kid Book, Practical Classroom Management Strategies 10-9<br />

The Tough Kid Social Skills Book 10-10<br />

The Tough Kid Tool Box 10-10<br />

The Tough Kid Video Series Kit 10-10<br />

The Walker Social Skills Curriculum 10-10<br />

• Suggested Websites 10-11<br />

• Resources <strong>for</strong> Classrooms: Variables Affecting Student <strong>Behavior</strong><br />

and Per<strong>for</strong>mance 10-11<br />

• Choosing an Observational Method 10-14<br />

• Survey: Preventing and Responding to Violent School Crises 10-15<br />

• At-a-Glance Comparison of Traditional <strong>Behavior</strong> Management<br />

and <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> 10-19<br />

• <strong>Michigan</strong>’s Ban of Corporal Punishment Law 10-20<br />

Section 11 – Assessment Tools on Disk 11-1<br />

Section 12 – Glossary 12-1<br />

Section 13 – References and <strong>Support</strong>ing Materials 13-1<br />

Section 14 – Reader Response 14-1<br />

Introduction – 10

Figures, Tables, Worksheets<br />

Section 2 – Assessing the Status of <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong><br />

in Your District<br />

• Figure 2.1 A Systems Approach to <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> 2-5<br />

• Figure 2.2 Change in Suspension Rates 2-7<br />

• Worksheet 2.1<br />

Assessing and Planning <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong><br />

in <strong>Schools</strong> 2-11<br />

• Worksheet 2.2 District-Wide System Program Indicators 2-12<br />

• Worksheet 2.3 Building-Based System Program Indicators 2-14<br />

• Worksheet 2.4 Classroom-Based System Program Indicators 2-16<br />

• Worksheet 2.5 Individual Student System Program Indicators 2-18<br />

• Worksheet 2.6<br />

<strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> Program Indicators<br />

Survey Summary 2-20<br />

Section 3 – Building a Model <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> Team<br />

• Worksheet 3.1 Checklist of Skills Needed by Student <strong>Support</strong><br />

Team Members 3-6<br />

• Worksheet 3.2 Sample <strong>Support</strong> Team Worksheet 3-7<br />

• Worksheet 3.3 Sample <strong>Support</strong> Team Report 3-8<br />

• Worksheet 3.4 <strong>Support</strong> Team Checklist 3-9<br />

• Worksheet 3.5 Sample Student <strong>Support</strong> Team Self-Assessment 3-10<br />

Section 4 – Completing a Functional Assessment of <strong>Behavior</strong><br />

• Figure 4.1 Functional Assessment of <strong>Behavior</strong> Model 4-5<br />

Section 5 – Collaborating on a <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> Intervention Plan<br />

• Figure 5.1 <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> Framework <strong>for</strong><br />

Addressing Learning and <strong>Behavior</strong> Problems 5-3<br />

• Worksheet 5.1 Initial Planning <strong>for</strong> Academic and <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong>:<br />

30-Minute Collaboration 5-5<br />

• Worksheet 5.2 Functional Assessment and <strong>Behavior</strong> Intervention<br />

Plan Worksheet 5-10<br />

• Worksheet 5.3 Sample <strong>Behavior</strong> Intervention Plan 5-12<br />

• Worksheet 5.4 Functional Assessment Checklist <strong>for</strong> Teachers and Staff 5-14<br />

Section 7 – Designing <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> Strategies<br />

• Table 7.1 Sociocultural Considerations regarding Culturally<br />

and Linguistically Diverse Children 7-9<br />

Introduction – 11

Section 1<br />

Exploring Beliefs<br />

and Defining<br />

<strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong>

Section 1<br />

Exploring Beliefs and Defining <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong><br />

If a student doesn’t know how to read, we teach.<br />

If a student doesn’t know how to swim, we teach.<br />

If a student doesn’t know how to multiply, we teach.<br />

If a student doesn’t know how to behave, we ...... punish?<br />

John Herner<br />

People need to take responsibility <strong>for</strong> teaching students how to behave. When<br />

school personnel, community agencies, families, and students adopt <strong>Positive</strong><br />

<strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> (PBS), academic and social skills will likely improve. The<br />

principles of PBS are applicable and appropriate <strong>for</strong> <strong>ALL</strong> students regardless of<br />

educational status. This document will help readers understand why <strong>Positive</strong><br />

<strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> is effective and necessary, who does it, how it is done, and<br />

how its success can be evaluated.<br />

What Is <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong>?<br />

<strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> is a broad-based set of proactive approaches integrated<br />

within comprehensive, schoolwide systems. Such systems are communities<br />

of concern that include parents, school personnel, students, and appropriate<br />

community agency personnel. This home/school/community system supports<br />

students in learning responsible behavior and achieving academic success.<br />

Who’s Involved?<br />

• Parents<br />

• Teachers<br />

• <strong>Support</strong> Staff<br />

• Student<br />

• Community<br />

• You!<br />

<strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong>: The Concept<br />

• PBS is a data-based ef<strong>for</strong>t.<br />

• PBS concentrates on adjusting the system that supports the student.<br />

• PBS is implemented by a collaborative, school-based team using personcentered<br />

planning.<br />

• The emphasis of intervention is on skill building.<br />

• Schoolwide expectations <strong>for</strong> prosocial behavior are clearly stated, widely<br />

promoted, and frequently referenced.<br />

• New contacts, positive experiences, powerful role models, and appropriate<br />

relationships are developed in this student-centered system.<br />

• It can require time (months to years) and patience to develop responsive systems;<br />

personalized settings; and appropriate, empowering, and enduring skills.<br />

Section 1 – 1

• Learning and behavior problems are assessed comprehensively. An ecological<br />

approach to assessment focuses on the identification of the student’s needs as<br />

well as on the student’s interaction within school, home, and community<br />

settings.<br />

• Functional assessment of learning and/or behavior challenges is linked to an<br />

intervention. The effectiveness of the selected intervention is evaluated and<br />

reviewed, leading to data-based revisions.<br />

• Change ef<strong>for</strong>ts focus on the use of positive interventions that support adaptive<br />

and prosocial behavior and build on the strengths of the student, leading<br />

to an improved quality of life.<br />

• Students are offered a continuum of methods to support appropriate behavior<br />

and to discourage violation of schoolwide expectations.<br />

• PBS thrives in a safe, well-planned, yet flexible system.<br />

• Dignity and self-esteem must be fostered <strong>for</strong> the student as well as <strong>for</strong> all those<br />

engaged in the process.<br />

Why?<br />

Addressed<br />

problems get<br />

resolved and<br />

stay solved<br />

Why Use <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong>?<br />

• Academic and/or behavior problems are effectively addressed through functional<br />

assessment of behavior.<br />

• Students benefit from modeling, system supports, and appropriate accommodations.<br />

• PBS complements a variety of teaching approaches and classroom discipline<br />

models.<br />

• A student’s behavior changes when it is understood by the student.<br />

• A student’s behavior changes when the student is involved in the process.<br />

• A student’s behavior changes when positive support is provided.<br />

• PBS is supported by research.<br />

• PBS works!<br />

When?<br />

Any time<br />

you need to<br />

better understand a<br />

pattern of<br />

behavior<br />

When Should <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> Be Implemented?<br />

• When supporting any learner’s academic and behavioral needs<br />

• When the behavior targeted <strong>for</strong> replacement or a new skill to be learned is<br />

selected, based on the educational needs of the student<br />

• At all times<br />

Section 1 – 2

What Does This Document Provide?<br />

• Strategies <strong>for</strong> self-assessment of your school system’s PBS status<br />

• A framework <strong>for</strong> implementation of <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>ALL</strong><br />

students<br />

• User friendly resources and references to extend your knowledge of PBS<br />

• Computer accessible materials<br />

• An opportunity <strong>for</strong> you to offer input to future revisions and obtain updates<br />

of this document<br />

Purpose of This Document<br />

• Improve quality of learning <strong>for</strong> <strong>ALL</strong> students<br />

• Define, place in context, and provide recommendations <strong>for</strong> the application of<br />

functional assessment and written plans of support using the <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong><br />

<strong>Support</strong> approach<br />

• Help local school districts build teams that will creatively utilize best practices<br />

to resolve behavior problems rather than rely on the “expert model”<br />

• <strong>Support</strong> the State Board of Education Goals and the State Improvement Plan<br />

• <strong>Support</strong> implementation of IDEA 97<br />

<strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> Implementation Plan<br />

• Produce a document of emerging promising practices <strong>for</strong> guidance in the use<br />

of <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> <strong>for</strong> students in the state of <strong>Michigan</strong><br />

• Provide training<br />

• Build sustained support <strong>for</strong> PBS through the <strong>Michigan</strong> <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong><br />

<strong>Support</strong> Intiative (see Resources, 10-2)<br />

How do you<br />

get there?<br />

• Action research<br />

• Make a plan<br />

• Utilize existing mechanisms <strong>for</strong> statewide dissemination of in<strong>for</strong>mation<br />

Anticipated Outcomes <strong>for</strong> <strong>Michigan</strong> Students<br />

• Increased student educational achievement:<br />

√<br />

√<br />

More time engaged in learning<br />

More classroom assignments completed<br />

Section 1 – 3

• Greater student self-control and self-determination:<br />

√<br />

√<br />

√<br />

√<br />

Fewer critical incidents: office referrals, suspensions, expulsions<br />

Improved school attendance<br />

Greater number of student-mediated conflict resolutions<br />

Fewer incidents of school and classroom rules violations<br />

Anticipated Benefits<br />

• Improved school climate<br />

• Improved interpersonal relationships<br />

• Reduced acts of violence in the school and community<br />

• Enhanced public confidence in education<br />

• Increased interagency collaboration<br />

• Increased student independence and community participation<br />

• Increased high school graduation rates<br />

• Reduced dependency on public assistance, corrections, and other public<br />

services and agencies<br />

• Ongoing evaluation and refinement of the system<br />

Section 1 – 4

Section 2<br />

Assessing the Status<br />

of <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong><br />

<strong>Support</strong> in Your District

Section 2<br />

Assessing the Status of <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong><br />

in Your District<br />

Don’t fix blame, fix the system.<br />

W. Edwards Deming<br />

<strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> (PBS) is a systems approach. A common core of<br />

beliefs about the needs of students and about the responsibility of the system to<br />

meet those needs must exist. Schoolwide policies and procedures that reflect<br />

those beliefs must be established.<br />

Getting Started with <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong><br />

• First, increase your school’s capacity to initiate and sustain new innovations<br />

through training and resources.<br />

• Then, clarify and communicate norms about behavior:<br />

Ready?<br />

Start...<br />

Go!<br />

√<br />

√<br />

√<br />

√<br />

√<br />

Review board policy.<br />

Establish school rules.<br />

Provide consistent en<strong>for</strong>cement of rules.<br />

Provide consistent and rich positive rein<strong>for</strong>cement.<br />

Communicate norms through system and school-wide campaigns.<br />

• Finally, establish effective academic support with high expectations.<br />

What Does Not Work?<br />

• Suspension, exclusion, punishment, and counseling when used in isolation<br />

• Focusing ef<strong>for</strong>t on a few kids and not paying attention to the foundation of<br />

the whole system<br />

• Simply attempting to control someone else’s behavior<br />

What Does Work?<br />

• Listening to a student’s words and addressing a student’s actions<br />

• Understanding that all behavior has a function<br />

Section 2 – 1

• Clear and concise schoolwide rules<br />

• Rules based on behaviors, not big ideas like, “Be respectful!”<br />

• Teaching and modeling the behaviors you expect in the classroom, hallway,<br />

cafeteria, bus, and other places<br />

• Rein<strong>for</strong>cement <strong>for</strong> following the rules, displaying expected behaviors, and<br />

achieving academic success<br />

• Immediate feedback to and correction of students when their behavior<br />

violates a rule (disciplinary action may also be required, but prompt feedback<br />

about what to do and how to behave is critical)<br />

What works?<br />

• Intensive focus on the five to seven percent of students who exhibit dangerous<br />

or chronic negative behavior through comprehensive instructional<br />

programs that assure learning <strong>for</strong> all students (United States Department of<br />

Education, Office of Special Education Programs, 1998), such as:<br />

•Study the problem<br />

•Make a plan<br />

•Engage student<br />

•Keep going!<br />

√<br />

√<br />

√<br />

√<br />

√<br />

√<br />

√<br />

Impulse control (i.e., self-monitoring leading to self-regulation)<br />

Anger management<br />

Stress management<br />

Responsible decision making<br />

Problem solving<br />

Peer mediation<br />

Attendance, positive conduct, and achievement rewards<br />

What Is the Foundation of <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong>?<br />

• School board members, superintendents, principals, and teachers making<br />

PBS a school improvement priority<br />

• Parent and community support of appropriate academic and social behavior<br />

• Student participation<br />

• Use of assessment-based, research-validated interventions<br />

• Team-driven planning and support<br />

• Visible and supportive leadership<br />

Features:<br />

• System-wide<br />

• Data-based<br />

• Student-centered<br />

What Are the Features of the <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> Approach?<br />

• Attention is paid to schoolwide practices <strong>for</strong> at-risk and high-risk students.<br />

• Staff practices with real-life examples using role-playing, modeling, and<br />

feedback on how to teach behavioral expectations in school, how to teach<br />

social skills, and how to maximize academic success and engagement.<br />

Section 2 – 2

• Schoolwide reward structure is in place.<br />

• Functional Assessment of <strong>Behavior</strong> is used <strong>for</strong> intervention planning.<br />

• Data are used to guide interventions.<br />

• Effective learning environments are created <strong>for</strong> students.<br />

• <strong>Support</strong> is provided <strong>for</strong> a student to help change his/her own behavior.<br />

What Types of Problems Does <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> Address?<br />

• High rates of problem behavior<br />

• Ineffective and punitive discipline processes<br />

• Lack of general and specialized behavioral interventions<br />

• Lack of staff support and cohesion<br />

• Negative school climate<br />

• High use of crisis/reactive management<br />

• Limited insight into student’s own behavior<br />

What Outcomes Are Emphasized Using <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong>?<br />

• Student-driven behavior change<br />

• Consistent implementation of effective practice<br />

• School policy and procedures that include PBS philosophy<br />

• Formalized problem solving<br />

• Improved quality of life<br />

What Does a Schoolwide <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> System Look Like?<br />

• Families are involved.<br />

• Community is supportive.<br />

Remember:<br />

Accent the<br />

positive!<br />

• Discipline procedures are well-defined and consistently implemented.<br />

• Appropriate behavior is taught.<br />

• Student behavior is monitored.<br />

• <strong>Positive</strong> behavior is recognized.<br />

Section 2 – 3

• Continuum of consequences <strong>for</strong> problem behavior is available.<br />

• Regular feedback on progress is disseminated to staff and students.<br />

• Staff is skilled in responding to students with learning and/or behavior<br />

problems.<br />

Where to Start?<br />

• Complete the schoolwide assessment and evaluation.<br />

• Set short- and long-term goals and objectives.<br />

• Develop and evaluate new procedures and systems.<br />

• Provide ongoing feedback to staff.<br />

• Involve community agencies and families at all times.<br />

When to Start?<br />

•Now!<br />

Section 2 – 4

<strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> Works!<br />

George Sugai and Robert Horner, researchers at the University of Oregon, direct<br />

the federally funded Center <strong>for</strong> <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> Interventions and <strong>Support</strong>.<br />

They have studied <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> (PBS) in over 65 schools in Oregon,<br />

Hawaii, Texas, and British Columbia. In those schools, the schoolwide approach<br />

defines, teaches, and encourages socially appropriate student behavior in elementary<br />

and middle schools. While 85% of the students have intact social skills, the<br />

school establishes an effective environment that frees teachers to better address<br />

the needs of students with challenging learning and behavior problems.<br />

The effective school environment has support from four sources (see Figure<br />

2.1). One, district/community support consists of developing policies and<br />

procedures philosophically aligned with the community’s and school’s missions.<br />

Two, schoolwide support consists of procedures and processes intended<br />

<strong>for</strong> <strong>ALL</strong> students and <strong>ALL</strong> staff. Specific setting support involves a team process<br />

that monitors school settings (e.g., cafeteria) where problem behaviors occur.<br />

The team develops strategies that prevent or minimize behavioral disturbances.<br />

Three, classroom support consists of routines and procedures through which<br />

teachers structure learning opportunities. Four, individual student support<br />

consists of immediate and effective responses to students who present significant<br />

behavior challenges. These intensive and individualized support systems<br />

may be needed <strong>for</strong> three to seven percent of students.<br />

Figure 2.1 A Systems Approach to <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong><br />

District/Community<br />

• Community, School Board & Superintendent with Aligned Philosophy<br />

• Policy<br />

• Procedures<br />

School<br />

• Principal’s Philosophy<br />

• Policy<br />

• Procedures<br />

Classroom<br />

• Teacher’s Philosophy<br />

• Policy<br />

• Procedure<br />

Student<br />

• Individual Per<strong>for</strong>mance<br />

Incentives<br />

• Functional Assessment<br />

of <strong>Behavior</strong><br />

• <strong>Behavior</strong><br />

<strong>Support</strong><br />

Plan<br />

Section 2 – 5

When Fern Ridge Middle School in Elmira, Oregon implemented <strong>Positive</strong><br />

<strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> on a schoolwide basis, a 42% drop in office referrals occurred<br />

over a one-year period. The school focused on defining and teaching expected<br />

behaviors, structured a reward system <strong>for</strong> displaying appropriate social behaviors<br />

throughout the school year, and used office referrals <strong>for</strong> inappropriate<br />

behaviors. Some students were required to check in daily at the counseling<br />

office in the morning and afternoon and to carry point cards to collect rewards<br />

<strong>for</strong> meeting school behavior expectations. For a few students, an individualized<br />

behavior plan was developed.<br />

Dr. Ron Nelson, an Arizona University researcher, found a dramatic decrease in<br />

office referrals after implementing a schoolwide approach. His consistent and<br />

systematic interpersonal response to disruptive behavior yielded significant<br />

results. By using a Think Time Strategy, teachers and students quickly ended any<br />

negative social exchanges, and teachers promptly engaged students in feedback<br />

and planning. With a Think Time area in each classroom, a disruptive behavior<br />

was interrupted early. The student talked to another teacher in another room<br />

about the problem, then completed a <strong>for</strong>m that addressed what went wrong and<br />

how to react differently next time. When the student’s response <strong>for</strong>m was<br />

approved by the cooperating teacher, the student returned to class. Office<br />

referrals decreased from over 700 annually to 71 in one year.<br />

Suzanne Schmick, Principal of Endicott Elementary-St. John Middle School in<br />

rural Washington state, confirms the success of the Think Time Strategy. She<br />

adds that it is important to make sure that the staff is in philosophical agreement<br />

and that sufficient training time and adequate follow-up support are<br />

provided. She also believes that limiting other school re<strong>for</strong>m initiatives at the<br />

same time allows teachers to focus on this strategy and to become proficient in<br />

its application. Further, she recommends networking with other schools using<br />

the approach and offering incentives <strong>for</strong> predicted positive results.<br />

In Westerly, Rhode Island in the 1990s, new leadership trans<strong>for</strong>med a district<br />

with 100 Office of Civil Rights violations into a model program <strong>for</strong> students,<br />

who now receive a continuum of support and services <strong>for</strong> behavior problems.<br />

The change to a PBS philosophy led to a change in practice. Policies <strong>for</strong> both<br />

prevention and intervention were developed, and over a four-year period,<br />

behavior problems were significantly reduced. In 1990, the district had 13 selfcontained<br />

classrooms <strong>for</strong> students with emotional and behavioral problems. By<br />

1994, only two self-contained classrooms remained. Westerly’s suspension and<br />

discipline statistics revealed significant improvement. Suspensions and discipline<br />

incidents dropped well below the state’s average and well below the average<br />

<strong>for</strong> districts of comparable size. The schools became safer and more productive<br />

<strong>for</strong> <strong>ALL</strong> students at all levels.<br />

Section 2 – 6

Two county school districts in Florida put a focus on teaching students social<br />

skills, problem-solving methods, and anger reduction techniques. Interventions<br />

were developed <strong>for</strong> academically and socially at-risk students. Since 1990, incidents<br />

of aggression and violence in the district have dropped. During the first<br />

three years of the program, disciplinary referrals were reduced by 28%, and<br />

suspensions dropped by one-third. In addition, grade retentions were reduced,<br />

and standardized test scores and academic per<strong>for</strong>mance improved. There were no<br />

student placements in the county’s alternative education program during the past<br />

four years. Figure 2.2 illustrates the significant reduction in suspension rates.<br />

Change in Suspension Rates<br />

14<br />

12<br />

P<br />

e<br />

r<br />

c<br />

e<br />

n<br />

t<br />

a<br />

g<br />

e<br />

10<br />

8<br />

6<br />

4<br />

9<br />

11<br />

Figure 2.2 Change in Suspension Rates<br />

2<br />

3<br />

3<br />

0<br />

0<br />

1989<br />

Year Be<strong>for</strong>e<br />

0<br />

1990<br />

Year 1<br />

0<br />

1991<br />

Year 2<br />

0<br />

1992<br />

Year 3<br />

Section 2 – 7

Randy’s Story:<br />

A Social Worker’s Perceptions<br />

regarding <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong><br />

Randy began life with many barriers to overcome. He was born to an unwed<br />

mother and his father was in jail. Randy also faced numerous medical problems.<br />

He had a hernia, poorly developed muscles, breathing problems, and low birth<br />

weight. His prognosis <strong>for</strong> healthy development was poor.<br />

Randy’s mother took him home from the hospital, held him, and cared <strong>for</strong> him<br />

<strong>for</strong> months. Gradually, he began to improve. However, Randy’s mother noticed<br />

that he did not seem to hear sounds that other children heard. Testing determined<br />

that Randy had a significant hearing loss and would eventually require<br />

special accommodations when he went to school.<br />

When he was five, Randy was enrolled in elementary school. He soon exhibited<br />

serious emotional and behavior problems. When Randy entered first grade, he<br />

was placed in a self-contained classroom <strong>for</strong> students with emotional impairment.<br />

Services provided by the school team and his mother’s support and<br />

assistance helped Randy gradually improve his behavior.<br />

By the fifth grade, Randy was able to function in a normal school setting, and he<br />

was mainstreamed into a regular classroom. However, there were still areas in<br />

which Randy required skilled support to be successful. He had problems with<br />

poor hygiene, immaturity, and occasional temper outbursts. Randy’s academic<br />

achievement was poor, as well. A system of <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> was<br />

implemented by the school team to help Randy remain in the general education<br />

program and to improve his social and academic functioning.<br />

As he grew older, Randy became a sports fanatic. The <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong><br />

team recognized his passion and used it to help him stay academically motivated<br />

and to expose him to positive male social role models. Even though his<br />

athletic prowess was just average, the junior high school coaches selected Randy<br />

to play football and basketball or made him a team manager or coach’s assistant.<br />

In the eighth grade, when Randy did not make the cut <strong>for</strong> the basketball team, one<br />

of his classmates privately went to the coach and begged him to make Randy the<br />

team manager. Understanding Randy’s needs, the coach agreed to do so.<br />

Randy gave his heart and soul to his sports endeavors, and his spirit prompted<br />

the coaches to create a place <strong>for</strong> him. With this teamwork, a small boy with a<br />

severe hearing impairment, attention deficit disorder, and a history of emotional<br />

difficulty, achieved success. His teammates and coaches respected him,<br />

Section 2 – 8

liked him, and helped him when he needed it. As a high school freshman, Randy<br />

has continued his involvement with school sports.<br />

Randy is now in ninth grade. His support team—which has included the elementary<br />

and middle school staffs, psychologist, social worker, high school staff,<br />

his mother, athletic director, coaches, principals, community mental health<br />

workers, grandparents, and counselors—has debated, planned, implemented<br />

plans, and worked hard to help Randy develop skills that now serve him well.<br />

For example, today, he is fully mainstreamed with the exception of one resource<br />

class, which af<strong>for</strong>ds him the opportunity to develop a connection with the<br />

special education teacher who will be a consistent, caring adult <strong>for</strong> all four years<br />

of high school. This is important because Randy’s grandparents are aging and<br />

his mother, who is frequently ill, often fails to provide Randy adequate supervision<br />

and direction.<br />

Recently, Randy was involved in a shoving match with another student. As a<br />

result of the incident, he was disciplined and told he had three days of in-house<br />

suspension. He became extremely upset, voiced his belief that this was unfair,<br />

and said he was “just going to leave the building and go home.” The school<br />

social worker was in<strong>for</strong>med of the situation by the special education teacher<br />

and, together, they intervened and prevented the temper outburst from escalating.<br />

Randy spent two days in the in-house suspension room. After role playing<br />

the situation with the social worker, he went to the principal and successfully<br />

negotiated the elimination of the third suspension day. The principal, aware of<br />

Randy’s ef<strong>for</strong>t to handle himself more maturely, saw this as a step <strong>for</strong>ward and<br />

rewarded it.<br />

Another positive support ef<strong>for</strong>t relates to Randy’s relatively under-developed<br />

social skills. He is often impulsive and acts without thinking. This problem is<br />

compounded by his hearing impairment, and he often misses speech nuances<br />

and connected mannerisms. Because Randy has had limited exposure to the<br />

larger world beyond his neighborhood, his support team has involved him in a<br />

social skills group to help him develop better social skills and contextual understanding.<br />

The group focuses on self-exploration, appropriate social behavior<br />

within the group and school setting, and discussions related to topics such as<br />

careers, personal goals, and dating.<br />

Randy’s progress, in spite of his many handicaps, has been remarkable. He has<br />

benefited from modeling, system supports, and appropriate accommodations.<br />

His mother and grandparents have collaborated with the school and with<br />

community members to build upon Randy’s strengths. The results have been<br />

very positive <strong>for</strong> Randy and rewarding to all those who have participated on his<br />

support team.<br />

Section 2 – 9

The Nature of the Approach<br />

<strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> is not a “cookbook” approach that is implemented in<br />

exactly the same way in every setting. Instead, it is an approach that can be<br />

contextualized to address the identification and development of the values,<br />

skills, and resources inherent in various settings. Toward that end, the survey<br />

worksheets that follow can be employed to ascertain which procedures and<br />

practices are in place and which need to be developed to assure learning and<br />

promote prosocial behavior across settings and communities. An additional<br />

worksheet is provided to help users organize survey results into useful, goaloriented<br />

in<strong>for</strong>mation. The “indicators” identified in this process can then serve<br />

as the basis <strong>for</strong> action planning and <strong>for</strong> verification of results.<br />

Section 2 – 10

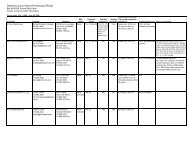

Assessing and Planning<br />

<strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> in <strong>Schools</strong><br />

Date:<br />

This survey is designed to help assess and plan <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> in schools. It was adapted<br />

from one survey developed by the Pennsylvania Department of Education and Department of<br />

Public Welfare in collaboration with a Tri-State Consortium on <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> (Knoster, 1999)<br />

and from another developed by Lewis and Sugai (1999). Often, a comprehensive approach to<br />

understanding the challenging behavior of students within a variety of school factors is necessary.<br />

This survey, which will assist teams in assessing the extent to which PBS indicators are in place,<br />

addresses district-wide indicators, building-based factors, classroom variables, and individual<br />

student considerations. Districts that use the survey may find policy and program areas in need of<br />

attention and other areas that are intact and functioning well. A listing of many factors related to<br />

<strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> in school follows.<br />

Name of School District:<br />

Name of School:<br />

Worksheet 2.1 Assessing and Planning <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> in <strong>Schools</strong><br />

Type of School: ❑ Elementary ❑ Middle/Junior High<br />

❑ High School<br />

❑ Alternative<br />

❑ Other:<br />

Total School Enrollment:<br />

Estimated number of students with chronic problem behaviors (i.e., students requiring extensive<br />

individualized support):<br />

Estimated number of days of expulsion and/or suspension <strong>for</strong> previous school year:<br />

Estimated number of office referrals <strong>for</strong> previous school year:<br />

Name of person completing the survey (optional):<br />

Position: ❑ Administrator ❑ General Educator<br />

❑ Special Educator<br />

❑ Parent/Family Member<br />

❑ Teacher Assistant<br />

❑ Counselor<br />

❑ School Psychologist ❑ School Social Worker<br />

❑ Community Member ❑ Student<br />

❑ Other:<br />

Knoster (1999)<br />

Section 2 – 11

Worksheet 2.2 District-Wide System Program Indicators<br />

District-Wide System Program Indicators<br />

The district-wide system of <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> includes the following:<br />

1. Space, staff, and time are provided <strong>for</strong> planning and<br />

implementing programs <strong>for</strong> all students’ social and<br />

emotional development across school buildings.<br />

2. Individualized options are available <strong>for</strong> supporting<br />

social-emotional development of all students and to<br />

instruct students in social skills (e.g., pro-social skills) as<br />

warranted across school buildings.<br />

3. An interpersonal problem-solving curriculum is taught<br />

within each school building.<br />

4. In-school counseling programs are available <strong>for</strong> students<br />

across school buildings.<br />

5. Each school building has a crisis prevention and intervention<br />

program in place (see Resources, page 10-15).<br />

6. <strong>Support</strong> programs are available <strong>for</strong> families across each<br />

school building.<br />

7. Clearly stated behavioral expectations and a support<br />

program that is designed to maximize student engagement<br />

in social and academic instruction are present<br />

across all school buildings.<br />

8. Administrative policies and procedures that support the<br />

inclusion of students with emotional and/or behavior<br />

support needs are in place across all buildings.<br />

9. The district’s discipline code has explicit exit criteria and<br />

a clearly articulated re-entry/transition process <strong>for</strong> return<br />

of students who were suspended as a result of a behavioral<br />

infraction.<br />

10. School specialists skilled in areas of social-emotional<br />

development are used to collaboratively enhance<br />

programs across all buildings.<br />

11. Transdisciplinary teams of teachers and specialists who<br />

are responsible <strong>for</strong> developing and monitoring all parts<br />

of district-wide programs are available <strong>for</strong> collaboration<br />

across buildings.<br />

12. The district has a local interagency plan.<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

(circle one)<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Evidence<br />

Adapted from Knoster (1999)<br />

Section 2 – 12

Worksheet 2.2 (con’t)<br />

District-Wide System Program Indicators<br />

The district-wide system of <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> includes the following:<br />

13. District policies are conducive to making available<br />

necessary supports to students who need additional<br />

help when emotional stressors significantly interfere<br />

with learning.<br />

14. Procedures are defined to design and implement<br />

personalized behavior support plans <strong>for</strong> students as<br />

needed in a consistent manner across all school<br />

buildings.<br />

15. A program coordinator, advisor, or administrator who<br />

functions across all buildings is responsible <strong>for</strong> overseeing/coordinating<br />

all aspects of behavior support plans<br />

<strong>for</strong> students who require individualized behavior<br />

support (this should be done in an integrated fashion<br />

within an individualized education program where<br />

appropriate).<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

(circle one)<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Evidence<br />

Please total the number of Yes/Somewhat/No responses circled above. Yes = , Somewhat = , No = . Place<br />

these totals in the spaces provided <strong>for</strong> District on the Survey Summary found on page 2-20.<br />

Adapted from Knoster (1999)<br />

Section 2 – 13

Worksheet 2.3 Building-Based System Program Indicators<br />

Building-Based System Program Indicators<br />

The building-based system of <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> includes the following:<br />

1. Space, staff, and time are provided <strong>for</strong> planning and<br />

implementing programs <strong>for</strong> all students’ social and<br />

emotional development within the school building.<br />

2. All classrooms operate/utilize a common/shared model<br />

of management within the building.<br />

3. Individualized options are available <strong>for</strong> supporting<br />

social-emotional development of all students and to<br />

instruct students in social skills (e.g., pro-social skills) as<br />

warranted within the building.<br />

4. An interpersonal problem-solving curriculum is taught<br />

and used by all staff with all students in the building.<br />

5. An in-school counseling program is available <strong>for</strong><br />

students in the building.<br />

6. A crisis prevention and intervention program is in place<br />

in the building (see Resources, page 10-15).<br />

7. <strong>Support</strong> programs are available <strong>for</strong> families who have<br />

children in the building.<br />

8. Clearly stated behavioral expectations and a support<br />

program that is designed to maximize student engagement<br />

in social and academic instruction within the<br />

building are present.<br />

9. Administrative policies and procedures that support the<br />

inclusion of students with emotional and/or behavior<br />

support needs are in place in the building.<br />

10. School specialists skilled in areas of social-emotional<br />

development are used to collaboratively enhance<br />

programs in the building.<br />

11. Transdisciplinary teams of teachers and specialists who<br />

are responsible <strong>for</strong> developing and monitoring all parts<br />

of school building programs are available within the<br />

building.<br />

12. The district’s local interagency plan has been operationally<br />

defined by staff in the building.<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

(circle one)<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Evidence<br />

Adapted from Knoster (1999)<br />

Section 2 – 14

Worksheet 2.3 (con’t)<br />

Building-Based System Program Indicators<br />

The building-based system of <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> includes the following:<br />

13. Planning room/space is available in the building <strong>for</strong><br />

students who need additional support when emotional<br />

stressors significantly interfere with learning (this is not<br />

a time out room).<br />

14. Procedures are defined to design and implement<br />

personalized behavior support plans <strong>for</strong> students as<br />

needed in a consistent manner within the building.<br />

15. A program coordinator, advisor, or supervisor/principal<br />

is responsible <strong>for</strong> overseeing/coordinating all aspects of<br />

behavior support plans <strong>for</strong> students in the building<br />

(this should be done in an integrated fashion as part of<br />

an individualized education program where appropriate).<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

(circle one)<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Evidence<br />

Please total the number of Yes/Somewhat/No responses circled above. Yes = , Somewhat = , No = . Place<br />

these totals in the spaces provided <strong>for</strong> School on the Survey Summary found on page 2-20.<br />

Adapted from Knoster (1999)<br />

Section 2 – 15

Worksheet 2.4 Classroom-Based System Program Indicators<br />

Classroom-Based System Program Indicators<br />

Each classroom-based system of <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> includes the following:<br />

1. A classroom statement/description concerning the<br />

rights and responsibilities (e.g., right to disagree, respect<br />

<strong>for</strong> people and property, responsibility <strong>for</strong> helping<br />

others) of students and staff is present .<br />

2. Clear behavioral expectations (i.e., rules and/or code of<br />

conduct) <strong>for</strong> everyone in the classroom exist .<br />

3. A classroom-based system of behavior support (i.e.,<br />

classroom management model) that establishes a<br />

conducive climate <strong>for</strong> growth and learning is in place.<br />

4. The classroom teacher/staff utilizes a common/shared<br />

classroom approach/model to management (e.g., all<br />

classrooms in the school building share one model/<br />

orientation to management.)<br />

5. Thoughtful organization of the classroom setting (e.g.,<br />

furnishings) exists to minimize overstimulation and<br />

problem behavior and to maximize safety, cooperation,<br />

and learning.<br />

6. An adequate staff/student ratio exists <strong>for</strong> including<br />

students with emotional and/or behavioral needs in<br />

typical classroom routines (e.g., academic instruction,<br />

social interaction).<br />

7. Direct, credible, and timely support exists <strong>for</strong> teacher/<br />

staff in each classroom to support students who have<br />

emotional and behavioral disorders.<br />

8. <strong>Support</strong> is available to each classroom teacher to modify<br />

the curriculum and/or change instructional design<br />

based on students’ cognitive and emotional strengths,<br />

with consideration given to each student’s:<br />

a. Instructional level in the curriculum<br />

b. Stress tolerance<br />

c. In<strong>for</strong>mation processing preferences and abilities<br />

d. Level of independent functioning (e.g., selfregulatory<br />

skills)<br />

e. Interests<br />

f. Overall quality of life<br />

9. Flexible time periods/limits are present in each classroom<br />

<strong>for</strong> social and academic activities in the classroom.<br />

Adapted from Knoster (1999)<br />

Section 2 – 16<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

(circle one)<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Evidence

Worksheet 2.4 (con’t)<br />

Classroom-Based System Program Indicators<br />

Each classroom-based system of <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> includes the following:<br />

10. An explicit classroom crisis intervention plan exists that<br />

includes:<br />

a. Consistent and explicit exit criteria<br />

b. Consistent and explicit re-entry criteria<br />

c. Specific procedure <strong>for</strong> processing incidents<br />

d. Emphasis on maximizing instructional time<br />

(see Resources, page 10-15)<br />

11. Classroom rules and management procedures that have<br />

been collaboratively determined and designed to<br />

maximize student ownership are present.<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

(circle one)<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Evidence<br />

Please total the number of Yes/Somewhat/No responses circled above. Yes = , Somewhat = , No = . Place<br />

these totals in the spaces provided <strong>for</strong> Classroom on the Survey Summary found on page 2-20.<br />

Adapted from Knoster (1999)<br />

Section 2 – 17

Worksheet 2.5 Individual Student System Program Indicators<br />

Individual Student System Program Indicators<br />

Each individual student system of <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> includes the following:<br />

1. Referral <strong>for</strong> multi-disciplinary evaluation <strong>for</strong> special<br />

education and/or behavior support can be accessed as<br />

needed.<br />

2. Each student’s local team has access to additional<br />

medical, mental health, and other community social<br />

services in a timely fashion.<br />

3. Where relevant, medication is used only as prescribed<br />

and is monitored frequently by each student’s local team.<br />

4. Other service agencies are available <strong>for</strong> each student<br />

who has a behavior support plan, and services (e.g.,<br />

mental health services, respite care, counseling) are<br />

effectively integrated with school services in an efficient<br />

manner.<br />

5. Circle of friends, a buddy system, or other supports are<br />

used to facilitate positive interpersonal relationships <strong>for</strong><br />

each particular student who has a behavior support plan.<br />

6. The school-wide Crisis Prevention Program can be<br />

tailored to meet needs of each particular student with a<br />

behavior support plan (see Resources, page 10-15).<br />

7. The academic curriculum is meaningful <strong>for</strong> each<br />

student who has a behavior support plan and can be<br />

adapted/modified to meet his/her needs.<br />

8. Each student who has a behavior support plan is<br />

involved in school-wide activities with developmentally<br />

appropriate peers to facilitate social skills development.<br />

9. A behavior support plan is based on a functional<br />

assessment and reflects multi-component strategies as<br />

designed by the team to meet the individual student’s<br />

needs.<br />

10. Family members are part of each student’s team and<br />

welcome to participate in meetings that are scheduled.<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

(circle one)<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Evidence<br />

Adapted from Knoster (1999)<br />

Section 2 – 18

Worksheet 2.5 (con’t)<br />

Individual Student System Program Indicators<br />

Each individual student system of <strong>Positive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>Support</strong> includes the following:<br />

11. A consistent school representative (e.g., counselor,<br />

school psychologist, social worker) provides family<br />

support or outreach contact with parents at least once<br />

every three weeks with regard to the behavior support<br />

plan.<br />

12. Parents of each student who has a behavior support<br />

plan have access to a family support group based on<br />

their expressed interest.<br />

13. Representatives from other service systems are in the<br />

school regularly <strong>for</strong> planning or reviewing each<br />

student’s program.<br />

14. A coordinated system of care is established in the<br />

community to meet the needs of each student who has a<br />

behavior support plan.<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

(circle one)<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Yes / Somewhat / No<br />

Evidence<br />