JUNE 2001 - UCLA School of Public Health

JUNE 2001 - UCLA School of Public Health

JUNE 2001 - UCLA School of Public Health

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

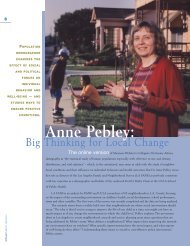

measure it and find places to intervene to prevent it. In my mind, that makes it<br />

a public health issue.”<br />

For a number <strong>of</strong> years, public health seemed to be the only field that viewed<br />

it that way. Now, there is a general consensus that criminologists and law enforcement<br />

represent only part <strong>of</strong> the solution, and that a multidisciplinary approach<br />

is needed. “It wasn’t until the 1990s that violence came to be widely recognized<br />

as a public health issue,” says Dr. Susan Sorenson, Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Community<br />

<strong>Health</strong> Sciences at the <strong>School</strong>. “There was a clear sense that approaching it only<br />

through the criminal justice system wasn’t working. The public health perspective<br />

brought a sense <strong>of</strong> hope and optimism that reducing violence wasn’t a futile<br />

endeavor. The idea <strong>of</strong> being able to prevent something from occurring rather<br />

than clamping down after the fact became very appealing.”<br />

Some may argue that violence has been a fact <strong>of</strong> life throughout history, in all<br />

societies. Whether the problem is worse now than in other times is debatable,<br />

particularly since surveillance began only recently. What is clear is that violence<br />

in American society is more lethal than it was in the past, due to the greater<br />

access to firearms. “The rest <strong>of</strong> the world doesn’t have the level <strong>of</strong> gun violence<br />

that we have,” says Weiss. But she believes it’s not only a weapons issue. “When<br />

you consider that the leading cause <strong>of</strong> death for children in this society between<br />

the perinatal period and age 1 is abuse, that’s pretty shocking,” she says. “There is<br />

Isabelle<br />

Barbour, M.P.H. ’00<br />

As the Outreach and<br />

Advocacy Coordinator at<br />

the Los Angeles Commission<br />

on Assaults Against Women<br />

(LACAAW), Barbour consults<br />

on violence prevention strategies<br />

with school districts and<br />

individual schools, as well as<br />

service agencies. Recently,<br />

Barbour and her colleagues<br />

at LACAAW met with<br />

Genethia Hayes, President<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Board <strong>of</strong> Education<br />

for the Los Angeles Unified<br />

<strong>School</strong> District (LAUSD),<br />

about the idea <strong>of</strong> developing<br />

a violence prevention policy<br />

for the district. Hayes was<br />

receptive, and asked<br />

LACAAW to draft a policy.<br />

Building on research she<br />

had done on the issue dating<br />

to her days as a <strong>UCLA</strong><br />

<strong>School</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong><br />

student, Barbour, along with<br />

Leah Aldridge, LACAAW’s<br />

Associate Director <strong>of</strong><br />

Youth Violence Prevention<br />

Programs, drafted a policy.<br />

“The point we have emphasized<br />

is that even though<br />

schools are a very safe<br />

place for youths, between<br />

the school shootings, bullying,<br />

and level <strong>of</strong> sexual<br />

harassment that occur,<br />

there’s a lot <strong>of</strong> fear,” Barbour<br />

says. “It’s very hard to learn<br />

in that climate, and it’s very<br />

hard to teach.” The policy<br />

Barbour co-wrote is currently<br />

being considered for implementation<br />

by LAUSD.<br />

“Violence is the<br />

leading cause<br />

<strong>of</strong> death and disability<br />

for the population<br />

under 35.<br />

You can measure<br />

it and find places<br />

to intervene to prevent<br />

it. In my mind,<br />

that makes it a<br />

public health issue.”<br />

—Billie Weiss, M.P.H. ’81<br />

Cathy Taylor<br />

Taylor, a Dr.P.H. student at<br />

the <strong>School</strong>, is working on a<br />

study headed by Dr. Susan<br />

Sorenson to assess social<br />

norms related to violence<br />

against women. Nearly 4,000<br />

interviews have been conducted<br />

with six ethnic groups<br />

in four languages. The survey,<br />

funded by the California<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> <strong>Health</strong><br />

Services, poses various<br />

scenarios about domestic<br />

violence to examine how<br />

individuals’ responses<br />

change depending on the<br />

characteristics <strong>of</strong> a given<br />

incident. “We need to educate<br />

people in ways that will<br />

reduce domestic violence,”<br />

says Taylor. “But it’s hard<br />

to do that without knowing<br />

where people are in their<br />

understanding and awareness<br />

<strong>of</strong> the issue.” Adds<br />

Taylor, who has a background<br />

in mental health:<br />

“From talking with people<br />

who grew up with violence<br />

or are currently in a violent<br />

situation, I feel strongly that<br />

violence prevention efforts,<br />

especially in families, can<br />

have a far-reaching impact<br />

on our society.”<br />

15<br />

cover story <strong>UCLA</strong>PUBLIC HEALTH