Investigative interviewing: the literature - New Zealand Police

Investigative interviewing: the literature - New Zealand Police

Investigative interviewing: the literature - New Zealand Police

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

REVIEW OF INVESTIGATIVE INTERVIEWING<br />

• confrontation - <strong>the</strong> research is clear that a person<br />

can be induced to confess and to accept<br />

responsibility for something <strong>the</strong>y didn’t do by tactics<br />

such as strongly asserting <strong>the</strong>y are guilty, interrupting<br />

denials, presenting false incriminating evidence, and<br />

saying <strong>the</strong>y failed a lie-detector test<br />

• minimisation - a process of providing or allowing <strong>the</strong><br />

suspect to make face-saving excuses for <strong>the</strong> event -<br />

implies leniency will follow (e.g., being allowed to go<br />

home or get a lighter sentence).<br />

A large body of research exists on this subject (see, for<br />

example, Gisli Gudjonsson, 1992) and false confessions<br />

have led to <strong>the</strong> conviction of many innocent people. The<br />

“Innocence Project” (a non-profit legal clinic at <strong>the</strong><br />

Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law, USA that handles<br />

cases where post-conviction DNA testing of evidence<br />

can yield conclusive proof of innocence) describes a<br />

case in point:<br />

“The problem of false confessions has been fur<strong>the</strong>r<br />

illuminated by <strong>the</strong> exoneration of five men - Antron<br />

McCray, Kevin Richardson, Yusef Salaam,<br />

Raymond Santana, and Kharey Wise - who were<br />

wrongfully convicted of a brutal attack in <strong>New</strong> York’s<br />

Central Park. DNA testing corroborated <strong>the</strong><br />

confession of Matias Reyes. Reyes stated that he<br />

acted alone and that he did not know <strong>the</strong> five men<br />

that were convicted in what is now known as <strong>the</strong><br />

Central Park Jogger Case. The five men, teenagers<br />

at <strong>the</strong> time, were picked up by police following a<br />

chaotic night in Central Park, marked by violence<br />

and what was termed “wilding”. Their statements to<br />

authorities were quite damning. Each gave a<br />

detailed videotaped statement minimizing his own<br />

involvement in <strong>the</strong> crime but implicating <strong>the</strong> rest.<br />

What <strong>the</strong> jury did not see were <strong>the</strong> tactics used to<br />

elicit <strong>the</strong>se statements, one of which came after<br />

over twenty four hours of interrogation. Despite <strong>the</strong><br />

fact that <strong>the</strong>ir accounts varied greatly, <strong>the</strong>se<br />

confessions were used to convict all five men, all of<br />

whom served out <strong>the</strong>ir sentences” (Innocence<br />

Project, 2001).<br />

Researchers Saul Kassin and Gisli Gudjonsson (2004)<br />

provide many more examples of false confessions in <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

recent comprehensive <strong>literature</strong> review on <strong>the</strong><br />

psychology of confessions. Their material makes it clear<br />

that police cannot ignore <strong>the</strong> results of research on why<br />

people confess to something <strong>the</strong>y did not do.<br />

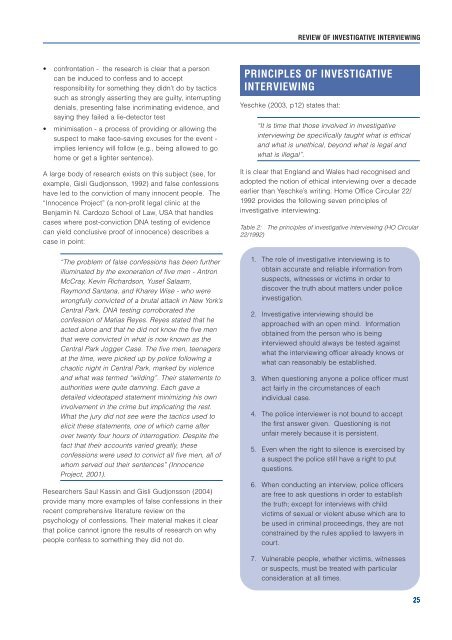

PRINCIPLES OF INVESTIGATIVE<br />

INTERVIEWING<br />

Yeschke (2003, p12) states that:<br />

“It is time that those involved in investigative<br />

<strong>interviewing</strong> be specifically taught what is ethical<br />

and what is unethical, beyond what is legal and<br />

what is illegal”.<br />

It is clear that England and Wales had recognised and<br />

adopted <strong>the</strong> notion of ethical <strong>interviewing</strong> over a decade<br />

earlier than Yeschke’s writing. Home Office Circular 22/<br />

1992 provides <strong>the</strong> following seven principles of<br />

investigative <strong>interviewing</strong>:<br />

Table 2: The principles of investigative <strong>interviewing</strong> (HO Circular<br />

22/1992)<br />

1. The role of investigative <strong>interviewing</strong> is to<br />

obtain accurate and reliable information from<br />

suspects, witnesses or victims in order to<br />

discover <strong>the</strong> truth about matters under police<br />

investigation.<br />

2. <strong>Investigative</strong> <strong>interviewing</strong> should be<br />

approached with an open mind. Information<br />

obtained from <strong>the</strong> person who is being<br />

interviewed should always be tested against<br />

what <strong>the</strong> <strong>interviewing</strong> officer already knows or<br />

what can reasonably be established.<br />

3. When questioning anyone a police officer must<br />

act fairly in <strong>the</strong> circumstances of each<br />

individual case.<br />

4. The police interviewer is not bound to accept<br />

<strong>the</strong> first answer given. Questioning is not<br />

unfair merely because it is persistent.<br />

5. Even when <strong>the</strong> right to silence is exercised by<br />

a suspect <strong>the</strong> police still have a right to put<br />

questions.<br />

6. When conducting an interview, police officers<br />

are free to ask questions in order to establish<br />

<strong>the</strong> truth; except for interviews with child<br />

victims of sexual or violent abuse which are to<br />

be used in criminal proceedings, <strong>the</strong>y are not<br />

constrained by <strong>the</strong> rules applied to lawyers in<br />

court.<br />

7. Vulnerable people, whe<strong>the</strong>r victims, witnesses<br />

or suspects, must be treated with particular<br />

consideration at all times.<br />

25