Investigative interviewing: the literature - New Zealand Police

Investigative interviewing: the literature - New Zealand Police

Investigative interviewing: the literature - New Zealand Police

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

REVIEW OF INVESTIGATIVE INTERVIEWING<br />

Evans and Webb (1993) suggest that interview training<br />

should involve practising with children. From <strong>the</strong> RCCJ<br />

study <strong>the</strong> crucial factor would appear to be around <strong>the</strong><br />

high rate of quick admissions. If this is common, <strong>the</strong>re<br />

should be little need for police to use tactics and<br />

questioning styles that may be seen as oppressive.<br />

General improvements in interview training whereby<br />

officers concentrate on engaging with <strong>the</strong> suspect and<br />

getting information that confirms <strong>the</strong> person’s guilt or<br />

establishes his or her innocence should have spin-offs<br />

for <strong>the</strong> <strong>interviewing</strong> of child suspects.<br />

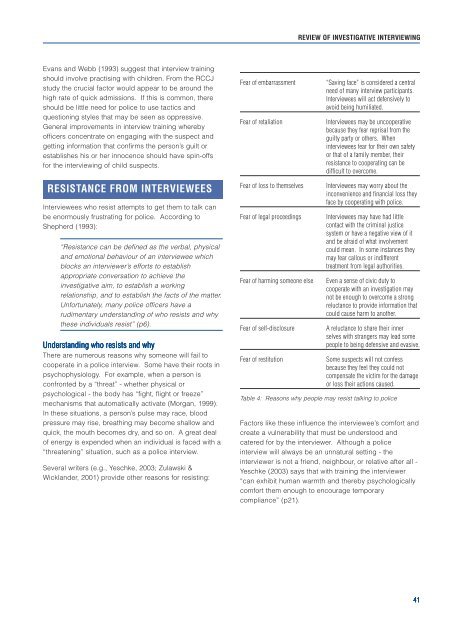

Fear of embarrassment<br />

Fear of retaliation<br />

“Saving face” is considered a central<br />

need of many interview participants.<br />

Interviewees will act defensively to<br />

avoid being humiliated.<br />

Interviewees may be uncooperative<br />

because <strong>the</strong>y fear reprisal from <strong>the</strong><br />

guilty party or o<strong>the</strong>rs. When<br />

interviewees fear for <strong>the</strong>ir own safety<br />

or that of a family member, <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

resistance to cooperating can be<br />

difficult to overcome.<br />

RESISTANCE FROM INTERVIEWEES<br />

Interviewees who resist attempts to get <strong>the</strong>m to talk can<br />

be enormously frustrating for police. According to<br />

Shepherd (1993):<br />

“Resistance can be defined as <strong>the</strong> verbal, physical<br />

and emotional behaviour of an interviewee which<br />

blocks an interviewer’s efforts to establish<br />

appropriate conversation to achieve <strong>the</strong><br />

investigative aim, to establish a working<br />

relationship, and to establish <strong>the</strong> facts of <strong>the</strong> matter.<br />

Unfortunately, many police officers have a<br />

rudimentary understanding of who resists and why<br />

<strong>the</strong>se individuals resist” (p6).<br />

Understanding who resists and why<br />

There are numerous reasons why someone will fail to<br />

cooperate in a police interview. Some have <strong>the</strong>ir roots in<br />

psychophysiology. For example, when a person is<br />

confronted by a “threat” - whe<strong>the</strong>r physical or<br />

psychological - <strong>the</strong> body has “fight, flight or freeze”<br />

mechanisms that automatically activate (Morgan, 1999).<br />

In <strong>the</strong>se situations, a person’s pulse may race, blood<br />

pressure may rise, breathing may become shallow and<br />

quick, <strong>the</strong> mouth becomes dry, and so on. A great deal<br />

of energy is expended when an individual is faced with a<br />

“threatening” situation, such as a police interview.<br />

Several writers (e.g., Yeschke, 2003; Zulawski &<br />

Wicklander, 2001) provide o<strong>the</strong>r reasons for resisting:<br />

Fear of loss to <strong>the</strong>mselves<br />

Fear of legal proceedings<br />

Fear of harming someone else<br />

Fear of self-disclosure<br />

Fear of restitution<br />

Interviewees may worry about <strong>the</strong><br />

inconvenience and financial loss <strong>the</strong>y<br />

face by cooperating with police.<br />

Interviewees may have had little<br />

contact with <strong>the</strong> criminal justice<br />

system or have a negative view of it<br />

and be afraid of what involvement<br />

could mean. In some instances <strong>the</strong>y<br />

may fear callous or indifferent<br />

treatment from legal authorities.<br />

Even a sense of civic duty to<br />

cooperate with an investigation may<br />

not be enough to overcome a strong<br />

reluctance to provide information that<br />

could cause harm to ano<strong>the</strong>r.<br />

A reluctance to share <strong>the</strong>ir inner<br />

selves with strangers may lead some<br />

people to being defensive and evasive.<br />

Some suspects will not confess<br />

because <strong>the</strong>y feel <strong>the</strong>y could not<br />

compensate <strong>the</strong> victim for <strong>the</strong> damage<br />

or loss <strong>the</strong>ir actions caused.<br />

Table 4: Reasons why people may resist talking to police<br />

Factors like <strong>the</strong>se influence <strong>the</strong> interviewee’s comfort and<br />

create a vulnerability that must be understood and<br />

catered for by <strong>the</strong> interviewer. Although a police<br />

interview will always be an unnatural setting - <strong>the</strong><br />

interviewer is not a friend, neighbour, or relative after all -<br />

Yeschke (2003) says that with training <strong>the</strong> interviewer<br />

“can exhibit human warmth and <strong>the</strong>reby psychologically<br />

comfort <strong>the</strong>m enough to encourage temporary<br />

compliance” (p21).<br />

41