Fall 2011 | Issue 21

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Contested Connotations<br />

David B. Ruderman on the legacy of ghettos in Jewish history<br />

News from the Hans Arnhold Center | Sketches & Dispatches | N9<br />

The word “ghetto” is<br />

one that rarely has positive<br />

connotations. This particularly<br />

applies to the case of the<br />

National Socialists’ persecution<br />

of Jews, where more often than<br />

not “ghetto” invokes depressing<br />

and inhumane images. Ghettos<br />

constructed by the National<br />

Socialists, primarily in Poland<br />

and Eastern Europe, were the<br />

intermediate stop for many on<br />

their way to extermination camps.<br />

Thus it is rather provocative to<br />

provide the assumption that<br />

ghettos could have also have had<br />

positive effects on the Jewish people.<br />

In the lecture series “History<br />

of the Jews in Italy,” at the Institute<br />

for Jewish Studies at the<br />

University of Potsdam, David B.<br />

Ruderman, professor of modern<br />

Jewish history at the University<br />

of Pennsylvania, focused on this<br />

exact question.<br />

“Are ghettos good or bad for<br />

Jews?” asked the US scholar in<br />

this year’s Emil Fackenheim<br />

Lecture. Ruderman is the author<br />

of several books on the topic of<br />

Jewish thought and modern Judaism.<br />

For 17 years he has directed<br />

the Herbert D. Katz Center for<br />

Advanced Judaic Studies at the<br />

University of Pennsylvania and<br />

in 2001 was honored for his life’s<br />

work by the National Foundation<br />

for Jewish Culture. Presently, he<br />

is working on a new book as the<br />

German Transatlantic Program<br />

Fellow at the American Academy<br />

in Berlin.<br />

Ruderman is aware that “ghetto”<br />

is an emotionally charged<br />

term; in the US it is predominantly<br />

associated with the word<br />

“isolation.” Venice’s first ghetto,<br />

constructed in 1516, demonstrated<br />

a reality that was quite different,<br />

however, argued Ruderman.<br />

In the decades and centuries to<br />

follow, Italian Jews, despite hardship<br />

and exclusion, were able to<br />

develop a vibrant Jewish cultural<br />

space. A turning point for Jewish<br />

life occurred in 1755, when Pope<br />

Paul IV decreed that Jews must<br />

live exclusively in ghettos.<br />

Almost every large Italian<br />

town had its own ghetto. Yet their<br />

Jewish inhabitants’ cultural identity,<br />

lifestyle, and amusements<br />

always remained open to their<br />

Christian neighbors. The ghettos<br />

for Italian Jews were also valued<br />

as “areas of retreat from dark reality”<br />

and vitalized the mystical traditions<br />

of Judaism. Furthermore,<br />

it was in this time that religious<br />

ceremonies became festive occasions<br />

for the first time, following<br />

their Catholic neighbors’ example,<br />

said Ruderman.<br />

This mutual, fruitful cultural<br />

exchange led Ruderman to the<br />

example of Jewish-Italian composer<br />

Salomone Rossi, whose<br />

works are reminiscent of baroque<br />

church music. Another applicable<br />

example can be seen in the notable<br />

writings of Venetian Rabbis<br />

Simone Luzatto and Leone de<br />

Modena, which, lacking the theme<br />

of the ghetto, would not be the<br />

works that they are. The scholar<br />

emphasized that he does not aim<br />

to romanticize medieval Jewish<br />

ghettos, but rather to demonstrate<br />

that one can interpret them as a<br />

place of refuge, as well as a space<br />

that provided Jews the possibility<br />

of having close contact with the<br />

non-Jewish environment.<br />

by Maren Herbst<br />

Published on May 25, <strong>2011</strong>,<br />

in Potsdamer Neueste<br />

Nachrichten<br />

Translated by Gretchen<br />

Graywall<br />

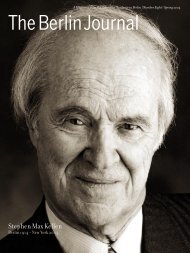

The Strains of Exile<br />

A violinist shares stories of his transcontinental past<br />

COURTESY HELLMUT STERN<br />

HELLMUT STERN AT AGE ELEVEN<br />

Hellmut Stern, former<br />

first violinist at the Berlin<br />

Philharmonic, opened<br />

his Academy talk on September 8,<br />

<strong>2011</strong>, with a deceptively simple<br />

statement: “I was an innocent<br />

child.” Stern’s subsequent recol-<br />

lections made these words all<br />

the more poignant, as the famed<br />

musician, now 82, described his<br />

dawning comprehension, as a<br />

ten-year-old, of the sinister currents<br />

shaping Germany in 1938.<br />

Shortly before his family fled,<br />

Stern witnessed the aftermath<br />

of Kristallnacht; arriving at<br />

his Jewish school, he found the<br />

building in flames, with terrified<br />

teachers urging the students to<br />

“go home, and stay there.”<br />

Stern did not go home. “I<br />

wanted to see everything,” he<br />

said, and continued further into<br />

town, the glass of broken store<br />

windows crunching beneath his<br />

steps, where he watched “normal<br />

people going inside [shops] and<br />

helping themselves.” The sight<br />

posed a question in his mind, one<br />

that still throbs: What would he<br />

have done, in their shoes? “You<br />

cannot condemn a whole people,”<br />

Stern said.<br />

From a feeling of belonging,<br />

of utter German-ness, Stern was<br />

thus forced to see himself as an<br />

outsider, and this psychology<br />

became physical as the Sterns<br />

finally secured visas to China<br />

and relocated to the frigid and<br />

foreign city of Harbin, a cosmopolitan<br />

hotbed of culture<br />

and political intrigue in the<br />

1920s, which had become part of<br />

Japanese-occupied Manchuria<br />

when the family arrived. There<br />

Stern would study violin under<br />

a stern taskmaster, Vladimir<br />

Trachtenberg, trained in the<br />

Russian school, who provided<br />

Stern with the discipline and<br />

attention that the young musician<br />

required to enter into his<br />

own as an undeniably exceptional<br />

talent.<br />

Despite the discomfort of<br />

dislocation, the agony of exile,<br />

and the cold and hunger of<br />

the Harbin years, Stern cited<br />

his parents, also gifted musi-