RACING PIGEONS â IMPACT OF RAPTOR PREDATION

RACING PIGEONS â IMPACT OF RAPTOR PREDATION

RACING PIGEONS â IMPACT OF RAPTOR PREDATION

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

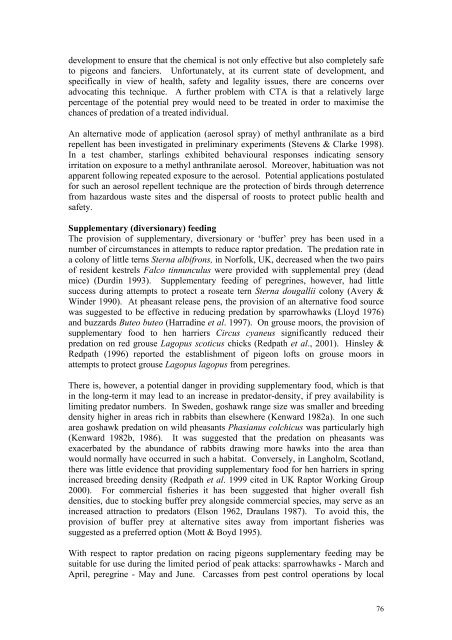

development to ensure that the chemical is not only effective but also completely safe<br />

to pigeons and fanciers. Unfortunately, at its current state of development, and<br />

specifically in view of health, safety and legality issues, there are concerns over<br />

advocating this technique. A further problem with CTA is that a relatively large<br />

percentage of the potential prey would need to be treated in order to maximise the<br />

chances of predation of a treated individual.<br />

An alternative mode of application (aerosol spray) of methyl anthranilate as a bird<br />

repellent has been investigated in preliminary experiments (Stevens & Clarke 1998).<br />

In a test chamber, starlings exhibited behavioural responses indicating sensory<br />

irritation on exposure to a methyl anthranilate aerosol. Moreover, habituation was not<br />

apparent following repeated exposure to the aerosol. Potential applications postulated<br />

for such an aerosol repellent technique are the protection of birds through deterrence<br />

from hazardous waste sites and the dispersal of roosts to protect public health and<br />

safety.<br />

Supplementary (diversionary) feeding<br />

The provision of supplementary, diversionary or ‘buffer’ prey has been used in a<br />

number of circumstances in attempts to reduce raptor predation. The predation rate in<br />

a colony of little terns Sterna albifrons, in Norfolk, UK, decreased when the two pairs<br />

of resident kestrels Falco tinnunculus were provided with supplemental prey (dead<br />

mice) (Durdin 1993). Supplementary feeding of peregrines, however, had little<br />

success during attempts to protect a roseate tern Sterna dougallii colony (Avery &<br />

Winder 1990). At pheasant release pens, the provision of an alternative food source<br />

was suggested to be effective in reducing predation by sparrowhawks (Lloyd 1976)<br />

and buzzards Buteo buteo (Harradine et al. 1997). On grouse moors, the provision of<br />

supplementary food to hen harriers Circus cyaneus significantly reduced their<br />

predation on red grouse Lagopus scoticus chicks (Redpath et al., 2001). Hinsley &<br />

Redpath (1996) reported the establishment of pigeon lofts on grouse moors in<br />

attempts to protect grouse Lagopus lagopus from peregrines.<br />

There is, however, a potential danger in providing supplementary food, which is that<br />

in the long-term it may lead to an increase in predator-density, if prey availability is<br />

limiting predator numbers. In Sweden, goshawk range size was smaller and breeding<br />

density higher in areas rich in rabbits than elsewhere (Kenward 1982a). In one such<br />

area goshawk predation on wild pheasants Phasianus colchicus was particularly high<br />

(Kenward 1982b, 1986). It was suggested that the predation on pheasants was<br />

exacerbated by the abundance of rabbits drawing more hawks into the area than<br />

would normally have occurred in such a habitat. Conversely, in Langholm, Scotland,<br />

there was little evidence that providing supplementary food for hen harriers in spring<br />

increased breeding density (Redpath et al. 1999 cited in UK Raptor Working Group<br />

2000). For commercial fisheries it has been suggested that higher overall fish<br />

densities, due to stocking buffer prey alongside commercial species, may serve as an<br />

increased attraction to predators (Elson 1962, Draulans 1987). To avoid this, the<br />

provision of buffer prey at alternative sites away from important fisheries was<br />

suggested as a preferred option (Mott & Boyd 1995).<br />

With respect to raptor predation on racing pigeons supplementary feeding may be<br />

suitable for use during the limited period of peak attacks: sparrowhawks - March and<br />

April, peregrine - May and June. Carcasses from pest control operations by local<br />

76