It Is Broken. Can It Be Fixed? A Look at the European Union's ...

It Is Broken. Can It Be Fixed? A Look at the European Union's ...

It Is Broken. Can It Be Fixed? A Look at the European Union's ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Submission Form<br />

Author’s Name:<br />

Affili<strong>at</strong>ion:<br />

Mailing Address:<br />

Richard F. Emery, Professor of Accounting<br />

Linfield College<br />

Business Department, Unit A478<br />

Linfield College<br />

900 SE Baker St.<br />

McMinnville, OR 97128<br />

Phone Number: (503)883-2298<br />

Fax Number: (503)883-2370<br />

E-mail Address:<br />

Title of Paper:<br />

rfemery@linfield.edu<br />

<strong>It</strong> <strong>Is</strong> <strong>Broken</strong>. <strong>Can</strong> <strong>It</strong> <strong>Be</strong> <strong>Fixed</strong>? A <strong>Look</strong> <strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>European</strong> Union’s<br />

Stability and Growth Pact<br />

<strong>It</strong> <strong>Is</strong> <strong>Broken</strong>. <strong>Can</strong> <strong>It</strong> <strong>Be</strong> <strong>Fixed</strong>? A <strong>Look</strong> <strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>European</strong> Union’s<br />

Stability and Growth Pact<br />

Richard F. Emery<br />

Linfield College<br />

Department of Business<br />

900 SE Baker Street<br />

McMinnville, OR 97128<br />

rfemery@linfield.edu<br />

(503) 883-2298

Paper Presented <strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> 30 th Annual <strong>European</strong> Studies Conference<br />

At <strong>the</strong> University of Nebraska <strong>at</strong> Omaha<br />

October 6-8, 2005<br />

Introduction<br />

In 1992, <strong>the</strong> <strong>European</strong> Union (EU), formerly <strong>the</strong> <strong>European</strong> Community, adopted <strong>the</strong><br />

Tre<strong>at</strong>y on <strong>European</strong> Union (TEU), more commonly known as <strong>the</strong> Maastricht Tre<strong>at</strong>y, in honor of<br />

<strong>the</strong> Dutch city where it was adopted. Perhaps <strong>the</strong> most significant aspect of <strong>the</strong> TEU was <strong>the</strong><br />

adoption of <strong>the</strong> three-stage process for completion of <strong>the</strong> <strong>European</strong> Monetary Union (EMU). In<br />

actuality, Stage I was already in existence, as it called for <strong>the</strong> free movement of capital within <strong>the</strong><br />

EU and for closer monetary and economic cooper<strong>at</strong>ion between <strong>the</strong> EU member st<strong>at</strong>es and <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

central banks. Both of <strong>the</strong>se had occurred with <strong>the</strong> completion of <strong>the</strong> Single Market <strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

beginning of 1992. In addition, Stage I adopted a time-line for <strong>the</strong> implement<strong>at</strong>ion of Stages II<br />

and III to guide <strong>the</strong> member st<strong>at</strong>es toward completion of EMU. Significantly, <strong>the</strong> TEU spelled<br />

out in Article 121, <strong>the</strong> requirements necessary for member st<strong>at</strong>es to be eligible to enter Stage III.<br />

These requirements became known as <strong>the</strong> convergence criteria:<br />

• Price stability: an average infl<strong>at</strong>ion r<strong>at</strong>e not exceeding by more than 1.5 percent<br />

th<strong>at</strong> of <strong>the</strong> three best-performing member st<strong>at</strong>es.<br />

2

• Budgetary discipline: a government financial position th<strong>at</strong> does not include an<br />

excessive deficit, a protocol <strong>at</strong>tached to <strong>the</strong> tre<strong>at</strong>y provided two reference values:<br />

a budget deficit of less than 3 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and a<br />

public debt r<strong>at</strong>io not exceeding 60 percent of GDP.<br />

• Currency stability: observance of normal fluctu<strong>at</strong>ion margins of <strong>the</strong> ERM<br />

(<strong>European</strong> R<strong>at</strong>e Mechanism) for <strong>at</strong> least two years with no devalu<strong>at</strong>ions.<br />

• Interest r<strong>at</strong>e convergence: an average nominal long-term interest r<strong>at</strong>e not<br />

exceeding by more than 2 percent th<strong>at</strong> of <strong>the</strong> three best-performing member<br />

st<strong>at</strong>es. (Dinan, 1999, p. 461).<br />

Among o<strong>the</strong>r things, Stage II called for <strong>the</strong> cre<strong>at</strong>ion of <strong>the</strong> <strong>European</strong> Monetary Institute<br />

(EMI), which was to be <strong>the</strong> forerunner of <strong>the</strong> <strong>European</strong> Central Bank (ECB), which would come<br />

into existence <strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> beginning of Stage III. The EMI came into existence in July 1994, and was<br />

loc<strong>at</strong>ed in Frankfurt, Germany, <strong>the</strong> se<strong>at</strong> of <strong>the</strong> German Bundesbank, a symbol, <strong>at</strong> least for <strong>the</strong><br />

Germans, of sound monetary policy. The EMI was given two major tasks: (a) make <strong>the</strong> technical<br />

prepar<strong>at</strong>ions necessary for Stage III of EMU; and (b) help coordin<strong>at</strong>e member st<strong>at</strong>es’ monetary<br />

policies. This l<strong>at</strong>ter task was difficult to accomplish because <strong>the</strong> EMI could not make decisions<br />

as <strong>the</strong> member st<strong>at</strong>es remained responsible for <strong>the</strong>ir own monetary policies until <strong>the</strong><br />

establishment of <strong>the</strong> ECB <strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> beginning of Stage III. To be fair, <strong>the</strong> member st<strong>at</strong>es did <strong>at</strong>tempt<br />

to coordin<strong>at</strong>e <strong>the</strong>ir monetary policies, but <strong>the</strong>y did so primarily through <strong>the</strong> auspices of <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>European</strong> Council’s Council of Economic and Finance Ministers (ECOFIN).<br />

The <strong>European</strong> Council asked ECOFIN to address two issues it believed central to <strong>the</strong><br />

success of EMU: (a) <strong>the</strong> problems posed by <strong>the</strong> fact th<strong>at</strong> not all member st<strong>at</strong>es would particip<strong>at</strong>e<br />

in EMU <strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> beginning of Stage III (if ever); and (b) how to insure th<strong>at</strong> member st<strong>at</strong>es would<br />

3

continue <strong>the</strong> budgetary discipline of <strong>the</strong> convergence criteria after <strong>the</strong> beginning of Stage III. Not<br />

surprising this second issue was critically important to Theo Waigel, German Finance Minister<br />

under Chancellor Helmut Kohl. In response to <strong>the</strong> <strong>European</strong> Council’s request for a methodology<br />

to continue <strong>the</strong> budgetary discipline, ECOFIN proposed wh<strong>at</strong> eventually became known as <strong>the</strong><br />

Stability and Growth Pact (SGP).<br />

The Stability and Growth Pact<br />

The genesis for <strong>the</strong> SGP is found in Article 104 of <strong>the</strong> TEU, which st<strong>at</strong>es in part:<br />

(1) Member St<strong>at</strong>es shall avoid excessive government deficits.<br />

(2) The Commission shall monitor <strong>the</strong> development of <strong>the</strong> budgetary situ<strong>at</strong>ion and of <strong>the</strong><br />

stock of government debt in <strong>the</strong> Member St<strong>at</strong>es with a view to identifying gross errors. In<br />

particular it shall examine compliance with budgetary discipline on <strong>the</strong> basis of <strong>the</strong><br />

following two criteria:<br />

(a) whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> r<strong>at</strong>io of <strong>the</strong> planned or actual government deficit to gross domestic<br />

product exceeds a reference value, unless: ei<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> r<strong>at</strong>io has declined<br />

substantially and continuously and reached a level th<strong>at</strong> comes close to <strong>the</strong><br />

reference value; or, altern<strong>at</strong>ively, <strong>the</strong> excess over <strong>the</strong> reference value is only<br />

exceptional and temporary and <strong>the</strong> r<strong>at</strong>io remains close to <strong>the</strong> reference value<br />

(b) whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> r<strong>at</strong>io of government debt to gross domestic product exceeds a<br />

reference value, unless <strong>the</strong> r<strong>at</strong>io is sufficiently diminishing and approaching <strong>the</strong><br />

reference value <strong>at</strong> a s<strong>at</strong>isfactory pace.<br />

(5) If <strong>the</strong> Commission considers th<strong>at</strong> an excessive deficit in a Member St<strong>at</strong>e exists or may<br />

occur, <strong>the</strong> Commission shall address an opinion to <strong>the</strong> Council.<br />

4

(9) If a Member St<strong>at</strong>e persists in failing to put into practice <strong>the</strong> recommend<strong>at</strong>ions of <strong>the</strong><br />

Council, <strong>the</strong> Council may decide to give notice to <strong>the</strong> Member St<strong>at</strong>e to take…measures<br />

for <strong>the</strong> deficit reduction which is judged necessary by <strong>the</strong> Council…<br />

(11) As long as a Member St<strong>at</strong>e fails to comply with a decision taken in accordance with<br />

paragraph (9), <strong>the</strong> Council may decide…to impose fines of an appropri<strong>at</strong>e size.<br />

(http://europa.eu.int.eur-lex/en/tre<strong>at</strong>ies/selected/livre223.html#anArt6).<br />

The reference values mentioned in parts 2 (a) and (b) of Article 104 above are <strong>the</strong> same as <strong>the</strong><br />

criteria established under <strong>the</strong> budgetary discipline portion of <strong>the</strong> convergence criteria in Article<br />

121 of <strong>the</strong> TEU, specifically, an annual budget deficit lower than 3 percent of GDP and a public<br />

debt not more than 60 percent of GDP, or <strong>at</strong> least approaching th<strong>at</strong> value.<br />

<strong>It</strong> is important to note th<strong>at</strong> <strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> time this discussion was occurring within ECOFIN,<br />

member st<strong>at</strong>es were desper<strong>at</strong>ely trying to s<strong>at</strong>isfy <strong>the</strong> convergence criteria. As part of member<br />

st<strong>at</strong>es’ efforts to s<strong>at</strong>isfy <strong>the</strong> convergence criteria several were cutting budgets in order to get <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

deficits below <strong>the</strong> magic 3 percent.<br />

As budget cuts resulted in less government hiring, fewer and smaller business subsidies,<br />

and lower expenditures on public works, unemployment inevitably increased. As budget<br />

cuts also resulted in less generous social welfare programs, unemployment became less<br />

congenial for many <strong>European</strong>s. These developments reinforced a popular perception th<strong>at</strong><br />

EMU itself caused unemployment and worsened <strong>the</strong> plight of <strong>the</strong> unemployed (Dinan,<br />

1999, p. 470).<br />

There are a couple of interesting political side notes to <strong>the</strong> proposal th<strong>at</strong> eventually<br />

became <strong>the</strong> SGP. Originally, <strong>the</strong> proposal was called <strong>the</strong> stability pact. However, when <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>European</strong> Council adopted <strong>the</strong> proposed agreement <strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> Dublin summit in December 1996,<br />

5

ECOFIN had renamed <strong>the</strong> pact, <strong>the</strong> SGP. This was in response to <strong>the</strong> perception th<strong>at</strong> EMU, or<br />

more specifically, <strong>the</strong> rush to meet <strong>the</strong> convergence criteria, was destroying jobs and cre<strong>at</strong>ing<br />

unemployment.<br />

When ECOFIN was drafting <strong>the</strong> SGP, German Finance Minister Waigel wanted <strong>the</strong> fines<br />

to become autom<strong>at</strong>ic. However, when <strong>the</strong> final proposal was adopted, fines were only one of <strong>the</strong><br />

possible recourses available for failure to stay within <strong>the</strong> 3 percent criteria. Fur<strong>the</strong>r, assessment<br />

of a fine was left to <strong>the</strong> discretion of <strong>the</strong> Council r<strong>at</strong>her than autom<strong>at</strong>ic. This was agreed to<br />

primarily appease <strong>the</strong> French, specifically President Jacques Chirac. <strong>It</strong> is ano<strong>the</strong>r example of how<br />

often, through <strong>the</strong> existence of <strong>the</strong> EU, <strong>the</strong> French and German governments have bent over<br />

backward to support <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r in order to preserve <strong>the</strong> primacy of <strong>the</strong> Franco-German<br />

rel<strong>at</strong>ionship in EU m<strong>at</strong>ters.<br />

Wh<strong>at</strong> is <strong>the</strong> SGP and wh<strong>at</strong> does it do? Formally, <strong>the</strong> SGP contains three elements:<br />

• A political commitment…to <strong>the</strong> full and timely implement<strong>at</strong>ion of <strong>the</strong> budget<br />

surveillance process…(which) ensures th<strong>at</strong> effective peer pressure is exerted on a<br />

Member St<strong>at</strong>e failing to live up to its commitments.<br />

• Preventive elements which through regular surveillance aim <strong>at</strong> preventing budget<br />

deficits going above <strong>the</strong> 3% reference value….<strong>It</strong> foresees <strong>the</strong> submission by all<br />

Member St<strong>at</strong>es of stability and convergence programs, which are examined by <strong>the</strong><br />

Council. The Regul<strong>at</strong>ion foresees also <strong>the</strong> possibility to trigger <strong>the</strong> early warning<br />

mechanism in <strong>the</strong> event a slippage in <strong>the</strong> budgetary position of a Member St<strong>at</strong>e is<br />

identified.<br />

6

• Dissuasive elements which in <strong>the</strong> event of <strong>the</strong> 3% reference value being breached,<br />

require Member St<strong>at</strong>es to take immedi<strong>at</strong>e corrective action and, if necessary,<br />

allow for <strong>the</strong> imposition of sanctions.<br />

(http://europa.eu.int/comm/economy_finance/about/activities/sgp/sgp_en.htm)<br />

The SGP does provide a couple of possible exceptions for failing to stay within <strong>the</strong> 3<br />

percent reference value:<br />

• <strong>It</strong> results from an unusual event outside <strong>the</strong> control of <strong>the</strong> Member St<strong>at</strong>e<br />

concerned and has a major impact on <strong>the</strong> financial position of <strong>the</strong> general<br />

government;<br />

• <strong>It</strong> results from a severe economic downturn (if <strong>the</strong>re is an annual fall of real GDP<br />

of <strong>at</strong> least 2%).<br />

(http://europa.eu.int/comm/economy_finance/about/activities/sgp/edp_en.htm)<br />

The SGP also clarifies <strong>the</strong> procedure for <strong>the</strong> imposition of fines. Initially, a member st<strong>at</strong>e must<br />

make a non-interest-bearing deposit with <strong>the</strong> Commission equal to 0.2 percent of GDP plus a<br />

variable amount based on <strong>the</strong> size of <strong>the</strong> deficit. Each succeeding year, <strong>the</strong> Council may require<br />

an additional deposit up to a maximum of 0.5 percent of GDP. The deposit may be converted<br />

into a fine if, in <strong>the</strong> opinion of <strong>the</strong> Council, <strong>the</strong> excessive deficit has not been corrected after two<br />

years.<br />

Deficit and Debt Results<br />

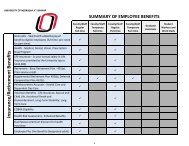

(Insert Table 1 about here)<br />

Table 1 presents <strong>the</strong> government deficit or surplus as a percentage of GDP for <strong>the</strong> years<br />

1998 through 2004. <strong>It</strong> is important to note th<strong>at</strong> only <strong>the</strong> 12 countries which are members of <strong>the</strong><br />

euro-zone are bound by <strong>the</strong> 3 percent reference value. O<strong>the</strong>r member st<strong>at</strong>es would have to s<strong>at</strong>isfy<br />

7

all <strong>the</strong> convergence criteria, including <strong>the</strong> 3 percent reference value, prior to becoming part of <strong>the</strong><br />

euro-zone. The following points summarize some of <strong>the</strong> more important inform<strong>at</strong>ion from Table<br />

1:<br />

• There has been a miniscule improvement in <strong>the</strong> deficit to GDP percentage for <strong>the</strong><br />

euro-zone 12 for 2004 when compared to 2003, -2.7 percent compared to -2.8<br />

percent. However, <strong>the</strong>re are only three member st<strong>at</strong>es th<strong>at</strong> are not in deficit –<br />

Finland, Ireland, and <strong>Be</strong>lgium, compared to five in 2003, as Luxembourg and<br />

Spain went into deficit. This is <strong>the</strong> first time th<strong>at</strong> Luxembourg has reported a<br />

deficit.<br />

• France and Germany, which account for more than half of EMU output, continue<br />

to have deficits significantly higher than 3 percent as <strong>the</strong>y have for <strong>the</strong> last three<br />

years. France did show modest improvement when compared to 2003, however,<br />

Germany remained essentially unchanged.<br />

• The situ<strong>at</strong>ion in Greece continues to worsen. The significant deterior<strong>at</strong>ion from<br />

<strong>the</strong> d<strong>at</strong>a reported for 2000 and prior when compared to 2001 and l<strong>at</strong>er call into<br />

question <strong>the</strong> accuracy of <strong>the</strong> earlier reported inform<strong>at</strong>ion. <strong>It</strong> is interesting to note<br />

th<strong>at</strong> Greece did not qualify for admission to <strong>the</strong> euro-zone until 2000, a year after<br />

<strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r 11 member st<strong>at</strong>es qualified. Perhaps Greece fudged its d<strong>at</strong>a in order to<br />

qualify.<br />

Although, <strong>the</strong> United Kingdom is not a member of <strong>the</strong> euro-zone, it is important to note<br />

th<strong>at</strong> its deficit to GDP percent exceeded <strong>the</strong> 3 percent reference value for both 2003 and 2004.<br />

This fact is quite interesting because <strong>the</strong> political rhetoric has long been th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> British economy<br />

8

is so strong th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> British don’t need to and shouldn’t join EMU. Perhaps it is time to end th<strong>at</strong><br />

myth.<br />

Again, although not part of EMU, all of <strong>the</strong> recently admitted member st<strong>at</strong>es have deficits<br />

when compared to GDP for 2004 with <strong>the</strong> exception of Estonia which had a surplus of 1.8<br />

percent. Malta -5.2 percent, Poland -4.8 percent, Hungary -4.5 percent, and Cyprus -4.2 percent<br />

had higher deficits than any of <strong>the</strong> euro-zone countries except for Greece.<br />

(Insert Table 2 about here)<br />

Table 2 presents <strong>the</strong> government debt as a percentage of GDP for <strong>the</strong> years 1998 through<br />

2004. As indic<strong>at</strong>ed above, <strong>the</strong> convergence criteria called for government debt of not more than<br />

60 percent of GDP. The following points summarize some of <strong>the</strong> more important inform<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

from Table 2:<br />

• Three countries – <strong>Be</strong>lgium, Greece, and <strong>It</strong>aly had debt to GDP r<strong>at</strong>ios considerable<br />

gre<strong>at</strong>er than 60 percent when <strong>the</strong>y joined <strong>the</strong> euro-zone. The reason <strong>the</strong>y were<br />

allowed to join EMU was because of <strong>the</strong> weasel words – approaching <strong>the</strong> value.<br />

Certainly, 105 to 120 percent is not really approaching 60 percent, however, wh<strong>at</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> table does not indic<strong>at</strong>e, is th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong>se percentages were, <strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> time, decreasing<br />

quite rapidly, again in order to be able to join EMU. This was particularly<br />

important for <strong>Be</strong>lgium and <strong>It</strong>aly since <strong>the</strong>y were founding members of <strong>the</strong> EU and<br />

it was unthinkable to not allow <strong>the</strong>m to join EMU if <strong>the</strong>y so desired. Both<br />

countries’ debt to GDP r<strong>at</strong>io has continued to decrease since <strong>the</strong> beginning of<br />

EMU, but obviously does not begin to approach <strong>the</strong> convergence criteria of 60<br />

percent.<br />

9

• As is <strong>the</strong> case with <strong>the</strong> deficit to GDP r<strong>at</strong>io, <strong>the</strong> debt to GDP r<strong>at</strong>io for France and<br />

Germany has worsened since 2001. Both countries now exceed <strong>the</strong> 60 percent<br />

reference value and continue to worsen. In addition, Portugal’s deficit to GDP<br />

r<strong>at</strong>io continues to worsen from its best year, 2000, and for <strong>the</strong> second year running<br />

is in excess of 60 percent.<br />

• The same comment concerning Greece’s d<strong>at</strong>a, as made above, is applicable here<br />

as well. Notice th<strong>at</strong> its debt to GDP percentage increased from 104.7 percent in<br />

2000 to 114.8 percent <strong>the</strong> next year, leading to <strong>the</strong> suspicion th<strong>at</strong> its d<strong>at</strong>a for 2000<br />

and earlier years was inaccur<strong>at</strong>e.<br />

• <strong>It</strong> is perhaps reasonable to conclude th<strong>at</strong> because ECOFIN’s primary focus has<br />

been on wh<strong>at</strong> to do about <strong>the</strong> deficit to GDP r<strong>at</strong>io, th<strong>at</strong> it has ignored <strong>the</strong> resulting<br />

debt to GDP r<strong>at</strong>io. In its 2002 report to <strong>the</strong> Council and <strong>the</strong> <strong>European</strong> Parliament,<br />

<strong>the</strong> Commission called for renewed <strong>at</strong>tention to <strong>the</strong> importance of debt.<br />

Only two of <strong>the</strong> newly admitted member st<strong>at</strong>es have a debt to GDP r<strong>at</strong>io in excess of <strong>the</strong><br />

60 percent reference point. Malta’s r<strong>at</strong>io is 75 percent while Cyprus’ r<strong>at</strong>io is 71.9 percent. At <strong>the</strong><br />

o<strong>the</strong>r extreme, Estonia is again <strong>the</strong> shining light. <strong>It</strong>s debt to GDP r<strong>at</strong>io is 4.9 percent, <strong>the</strong> lowest<br />

of <strong>the</strong> EU-25.<br />

Critique of <strong>the</strong> Stability and Growth Pact<br />

The original goal of <strong>the</strong> Stability and Growth Pact was to safeguard <strong>the</strong> sustainability of<br />

public finances in EMU. However, according to some experts, this goal has become less clear<br />

over time, moving towards <strong>the</strong> more ambitious goals of ensuring th<strong>at</strong> all countries follow<br />

sensible, if not optimal, fiscal policies. The Stability and Growth Pact is viewed as too intrusive<br />

and aggressive to achieve <strong>the</strong> original goal of sustainability of public finances. On <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

10

hand, its rules are not strict enough to enforce optimal fiscal policies. Obviously, <strong>the</strong> Stability<br />

and Growth Pact cannot achieve both goals.<br />

The 3% deficit limit and <strong>the</strong> 60% debt limit were originally chosen to be consistent with<br />

a stable debt r<strong>at</strong>io and a trend annual growth r<strong>at</strong>e of nominal GDP of 5%. With 5%<br />

growth, <strong>the</strong> increase in debt implied by a 3% deficit exactly offsets <strong>the</strong> reduction in a debt<br />

r<strong>at</strong>io of 60%. <strong>It</strong> is now clear, however, th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> EMU countries did not and will not grow<br />

uniformly <strong>at</strong> a r<strong>at</strong>e of 5% annually. Some countries achieved growth r<strong>at</strong>es significantly<br />

above th<strong>at</strong> r<strong>at</strong>e; o<strong>the</strong>rs, Germany and France in particular, achieved less than th<strong>at</strong><br />

(F<strong>at</strong>as,Von Hagen, Hallett, Strauch, and Sibert, 2003, p. 51).<br />

As a result, slow growing economies, like France and Germany, can experience rising debt r<strong>at</strong>ios<br />

(which <strong>the</strong>y have), even if <strong>the</strong>y stay below <strong>the</strong> 3 percent deficit limit (which <strong>the</strong>y haven’t). For<br />

countries with high growth r<strong>at</strong>es, especially <strong>the</strong> newly acceded countries, <strong>the</strong> 3 percent deficit<br />

limit will prove unduly restrictive. In short, <strong>the</strong>se limits are simply not flexible enough.<br />

Henrik Enderlein suggests th<strong>at</strong> fiscal policy within a monetary union is really a C<strong>at</strong>ch-22<br />

situ<strong>at</strong>ion.<br />

The conduct of domestic fiscal policies in a monetary union is subject to two largely<br />

opposite requirements. On <strong>the</strong> one hand, member countries need to be given some<br />

autonomy to undertake stabilizing fiscal measures in <strong>the</strong> domestic economy. On <strong>the</strong><br />

o<strong>the</strong>r hand, member countries’ fiscal autonomy needs to be reduced if <strong>the</strong>re is a<br />

credible risk th<strong>at</strong> a country seeks free-riding on overall systemic stability (Enderlein,<br />

2004, p. 1039).<br />

He suggests th<strong>at</strong> by definition <strong>the</strong> focus of <strong>the</strong> SGP is on <strong>the</strong> l<strong>at</strong>ter requirement and th<strong>at</strong> based on<br />

<strong>the</strong> first six years of EMU, this requirement should be given much less emphasis.<br />

11

Ano<strong>the</strong>r concern is th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> rules are difficult to enforce. Leaving enforcement to<br />

ECOFIN is akin to having <strong>the</strong> fox guard <strong>the</strong> henhouse. This has definitely come to pass, as<br />

evidenced by <strong>the</strong> fact th<strong>at</strong> France and Germany have yet to be penalized, although <strong>the</strong>y have<br />

been thre<strong>at</strong>ened with penalties for exceeding <strong>the</strong> 3 percent deficit limit. Although this paper has<br />

not gone into detail as to how a member st<strong>at</strong>e can be fined for exceeding <strong>the</strong> 3 percent deficit<br />

limit, suffice it to say th<strong>at</strong> a fine is not autom<strong>at</strong>ic, although th<strong>at</strong> very well may be <strong>the</strong> public<br />

perception. Never<strong>the</strong>less, <strong>the</strong> fact th<strong>at</strong> France and Germany have not been penalized does suggest<br />

th<strong>at</strong> larger member st<strong>at</strong>es can ignore <strong>the</strong> reference values to no harm. The inference being th<strong>at</strong><br />

this is a luxury th<strong>at</strong> would not be afforded to smaller member st<strong>at</strong>es. Whe<strong>the</strong>r this is true or not is<br />

certainly open to specul<strong>at</strong>ion. However, it has been cited as <strong>at</strong> least one of <strong>the</strong> many factors<br />

which led <strong>the</strong> Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands to reject <strong>the</strong> Constitutional Tre<strong>at</strong>y this past May.<br />

In fairness, not everyone believes th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> fault lies entirely, or even primarily with <strong>the</strong><br />

SGP.<br />

There is plenty wrong with <strong>the</strong> SGP – <strong>the</strong> arbitrariness of <strong>the</strong> 3 percent rule, <strong>the</strong><br />

consequent pro-cyclical tendencies, and <strong>the</strong> insufficient room for maneuver it allows to<br />

countries, such as Germany, where <strong>the</strong> one-size-fits all monetary policy is particularly<br />

restrictive....But <strong>the</strong> objective of fiscal discipline which <strong>the</strong> SGP so clumsily and rigidly<br />

pursues is not wrong….The main problem, from which <strong>the</strong> SGP controversy distracts<br />

<strong>at</strong>tention, is <strong>the</strong> <strong>European</strong> Central Bank’s excessive restrictive policy orient<strong>at</strong>ion (Martin,<br />

2005, p. 7).<br />

The ECB has long claimed th<strong>at</strong> its only purpose is to pursue price stability, e.g. control infl<strong>at</strong>ion.<br />

Never<strong>the</strong>less, Martin argues th<strong>at</strong> in its pursuit of price stability, <strong>the</strong> ECB reacted too little, too<br />

l<strong>at</strong>e when economic growth slowed in <strong>the</strong> early 2000s. The unfortun<strong>at</strong>e result was th<strong>at</strong> member<br />

12

st<strong>at</strong>es’ revenue failed to grow <strong>at</strong> sufficient levels to m<strong>at</strong>ch <strong>the</strong> resulting social policy costs<br />

imposed upon <strong>the</strong>m by <strong>the</strong> economic slow down. The result was th<strong>at</strong> it became exceedingly<br />

difficult, if not impossible, for some member st<strong>at</strong>es to s<strong>at</strong>isfy <strong>the</strong> SGP’s requirements,<br />

specifically, <strong>the</strong> 3 percent reference value.<br />

In summary, it is probably reasonable to conclude th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> SGP has not been as effective<br />

as was believed it would be when first introduced and agreed to nearly a decade ago. Most<br />

experts would probably agree with <strong>the</strong> following sentiment:<br />

The SGP has achieved two things. First, it shifts <strong>the</strong> n<strong>at</strong>ure of fiscal framework<br />

significantly towards a rule-based concept constraining annual deficits and away from a<br />

framework based on informed judgment. Second, it weakens <strong>the</strong> position of <strong>the</strong> <strong>European</strong><br />

Commission in <strong>the</strong> process, to <strong>the</strong> benefit of ECOFIN….As a result, <strong>the</strong> process and<br />

decisions taken under it have become more politicized (F<strong>at</strong>as, von Hagen, Hallett,<br />

Strauch, and Sibert, 2003, p. 9).<br />

Proposals for Improvement<br />

In an effort to improve <strong>the</strong> SGP, in l<strong>at</strong>e 2002, <strong>the</strong> Commission put forward a proposal<br />

entitled, Streng<strong>the</strong>ning <strong>the</strong> Coordin<strong>at</strong>ion of Budgetary Policies. The proposal started with a<br />

listing of six problems th<strong>at</strong> exist with <strong>the</strong> EU’s fiscal policy, specifically, <strong>the</strong> shortcomings of <strong>the</strong><br />

SGP. The problems include:<br />

• Decline in political ownership of <strong>the</strong> SGP by <strong>the</strong> member st<strong>at</strong>es.<br />

• Lack of identific<strong>at</strong>ion of clear and verifiable budget objectives.<br />

• Fiscal policies have been sufficiently lax so th<strong>at</strong> governments have not been able to stay<br />

below deficit targets during times of slow economic growth.<br />

• Enforcement has been poor.<br />

13

• Flexibility is lacking.<br />

• Difficulty in communic<strong>at</strong>ion and d<strong>at</strong>a collection.<br />

As a result <strong>the</strong> Commission made <strong>the</strong> following recommend<strong>at</strong>ions for reform:<br />

• Add flexibility to <strong>the</strong> rules. An example would be to allow <strong>the</strong> use of cyclically adjusted<br />

variables when assessing medium-term budgetary plans. Ano<strong>the</strong>r example would be to<br />

allow small devi<strong>at</strong>ions from <strong>the</strong> “close-to-balance or in surplus” rules, particularly for<br />

countries th<strong>at</strong> have low debt/GDP r<strong>at</strong>ios.<br />

• Increase political ownership. In o<strong>the</strong>r words, all countries must agree th<strong>at</strong> sustainability<br />

of public finances is a core objective.<br />

• Reinforce surveillance. Establish an early warning system, whereby countries would have<br />

sufficient time to change fiscal policy before falling into a situ<strong>at</strong>ion of excessive deficits.<br />

• Recognize th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> level of debt m<strong>at</strong>ters. Provide gre<strong>at</strong>er incentives for debt reduction,<br />

while penalizing debt increasing behavior.<br />

• Upgrade st<strong>at</strong>istics and improve communic<strong>at</strong>ion. There should be non-partisan<br />

enforcement whereby <strong>the</strong> Commission implements <strong>the</strong> rules, r<strong>at</strong>her than <strong>the</strong> current<br />

practice where implement<strong>at</strong>ion is left to ECOFIN.<br />

F<strong>at</strong>as, von Hagen, Hallett, Strauch, and Sibert identified four altern<strong>at</strong>ive proposals which put<br />

sustainability of public funds as <strong>the</strong> main objective, but differ from <strong>the</strong> strict limits on deficits<br />

and debt. These proposals include:<br />

• The Golden Rule. The Golden Rule argues th<strong>at</strong> it is not <strong>the</strong> size of <strong>the</strong> deficit th<strong>at</strong> m<strong>at</strong>ters<br />

so much as <strong>the</strong> composition of <strong>the</strong> expenditures. Larger deficits can be allowed, but only<br />

if <strong>the</strong> deficit is <strong>the</strong> result of public expenditures. This rule is currently followed by both<br />

Germany and <strong>the</strong> United Kingdom.<br />

14

• Debt rules. The argument here is th<strong>at</strong> sustainability rel<strong>at</strong>es more to <strong>the</strong> debt burden than<br />

to <strong>the</strong> current deficit. An applic<strong>at</strong>ion of this focus is th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> deficit criterion should be<br />

loosened for countries with low debt r<strong>at</strong>ios. Governments would tighten <strong>the</strong>ir budgets in<br />

good times in order to lower <strong>the</strong>ir debt r<strong>at</strong>ios and in bad times could expand <strong>the</strong>ir deficit<br />

r<strong>at</strong>io, while keeping <strong>the</strong>ir debt r<strong>at</strong>io stable, or so <strong>the</strong> argument goes.<br />

• Country-specific rules. This would allow countries more flexibility in addressing <strong>the</strong><br />

deficit and debt situ<strong>at</strong>ions. Countries would be encouraged to come up with individual<br />

solutions such as Sweden’s proposal for <strong>the</strong> cre<strong>at</strong>ion of a stabiliz<strong>at</strong>ion fund to enhance<br />

employment and wage stability in bad times. This would require, for example, a system<br />

of tax smoothing.<br />

• Cushion funds. Essentially, endorse <strong>the</strong> Swedish proposal, something th<strong>at</strong> Finland has<br />

also done, but do it on a community-wide basis.<br />

As indic<strong>at</strong>ed, <strong>the</strong>se proposals all regard sustainability as <strong>the</strong> main objective of <strong>the</strong> SGP and see<br />

<strong>the</strong> current rules as ineffective in meeting <strong>the</strong> objective.<br />

F<strong>at</strong>as, von Hagen, Hallett, Strauch, and Sibert have concluded th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> current system is<br />

broken and needs to be fixed. To do so <strong>the</strong>y have proposed <strong>the</strong> cre<strong>at</strong>ion of, wh<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong>y call, a<br />

Sustainability Council for <strong>the</strong> EMU countries.<br />

The Sustainability Council’s task would be to provide an informed assessment of <strong>the</strong><br />

fiscal situ<strong>at</strong>ion and outlook of each EMU member st<strong>at</strong>e, taking into account all relevant<br />

aspects of <strong>the</strong> situ<strong>at</strong>ion. This would bring <strong>the</strong> fiscal policy framework of EMU back to <strong>the</strong><br />

spirit of <strong>the</strong> Maastricht Tre<strong>at</strong>y and <strong>the</strong> original EDP (excessive deficit procedure).<br />

Importantly, however, by entrusting <strong>the</strong> analysis and judgment of sustainability to an<br />

independent council, it would solve <strong>the</strong> basic credibility problem of <strong>the</strong> SGP, th<strong>at</strong> is th<strong>at</strong><br />

15

<strong>the</strong> governments through ECOFIN judge <strong>the</strong> quality of <strong>the</strong>ir own policies (F<strong>at</strong>as, Von<br />

Hagen, Hallett, Strauch, and Sibert, 2003, p. 67).<br />

They suggest th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> Sustainability Council be funded by and report to <strong>the</strong> <strong>European</strong> Parliament,<br />

r<strong>at</strong>her than ei<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> Commission or <strong>the</strong> Council. They acknowledge th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> idea for cre<strong>at</strong>ion of<br />

yet ano<strong>the</strong>r EU institution may seem un<strong>at</strong>tractive to many. However, <strong>the</strong>y feel th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> benefits of<br />

increased transparency and democracy outweigh this concern and warrant consider<strong>at</strong>ion of <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

proposal.<br />

Enderlein suggests th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> problem for EMU is “how to achieve domestically stabilizing<br />

fiscal policies without cre<strong>at</strong>ing a collective action problem based on free-riding deficit-spending<br />

by member countries’ governments” (Enderlein, 2004, p. 1042). He suggests two possible<br />

solutions: (a) a full-fledged system of fiscal federalism wherein any surplus money from fast<br />

growing member st<strong>at</strong>es would be redistributed to low growth countries; and (b) abolishment of<br />

<strong>the</strong> SGP replacing it with reliance on Article 99 of <strong>the</strong> TEU’s Broad Economic Policy Guidelines<br />

(BEPGs).<br />

Of <strong>the</strong>se solutions, Enderlein suggests th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> first, while having some appeal, is<br />

unrealistic, <strong>at</strong> least <strong>at</strong> this juncture. Therefore, he recommends scraping <strong>the</strong> SGP and relying on<br />

wh<strong>at</strong> is referred as <strong>the</strong> ‘soft’ approach of <strong>the</strong> BEGPs. He argues th<strong>at</strong> decisions on deficits and<br />

surpluses are fundamentally political in n<strong>at</strong>ure and, <strong>the</strong>refore, <strong>the</strong> ‘hard’ approach of <strong>the</strong> SGP<br />

will not work. He distinguishes between <strong>the</strong> two approaches with <strong>the</strong> following example: “<strong>the</strong><br />

SGP approach: ‘you are not allowed to run deficits above 3 per cent’…<strong>the</strong> BEPG approach: in<br />

2004 you should reach a budgetary deficit of 1 per cent’” (Enderlein, 2004, p. 1042). Whe<strong>the</strong>r<br />

this is merely a m<strong>at</strong>ter of semantics or is a significant difference is probably a m<strong>at</strong>ter of<br />

interpret<strong>at</strong>ion, however, Article 99 does task <strong>the</strong> Council with <strong>the</strong> formul<strong>at</strong>ion of <strong>the</strong>se BEGPs<br />

16

with a subsequent report to <strong>the</strong> <strong>European</strong> Parliament. Enderlein’s argument is th<strong>at</strong> it is through<br />

<strong>the</strong> workings of <strong>the</strong> Council th<strong>at</strong> member st<strong>at</strong>es will be pressured to insure th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir fiscal<br />

policies do not allow for significant free-riding deficit-spending making <strong>the</strong> SGP unnecessary.<br />

Martin’s solution is th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> ECB accept responsibility for growth as well as price<br />

stability, as <strong>the</strong> United St<strong>at</strong>es’ Federal Reserve Bank has done.<br />

Fiscal discipline would <strong>the</strong>n have to be reconfigured. While member st<strong>at</strong>es would get<br />

more scope for adjustment to <strong>the</strong>ir diverse conditions, <strong>the</strong>ir fiscal policies would have to<br />

be coordin<strong>at</strong>ed so th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong>y add up to overall euro zone fiscal stance th<strong>at</strong>, combined with<br />

a more expansionary monetary stance, gives <strong>the</strong> euro zone a macroeconomic policy mix<br />

aimed <strong>at</strong> growth as well as reasonably low infl<strong>at</strong>ion. At a minimum, such coordin<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

would require shifting <strong>the</strong> focus of <strong>the</strong> BEPGs to <strong>the</strong> euro zone policy mix, including<br />

monetary as well as fiscal policy. This would, in turn, require <strong>the</strong> ECB to negoti<strong>at</strong>e with<br />

<strong>the</strong> Commission and <strong>the</strong> Euro Group in Ecofin about <strong>the</strong> respective policy stances to be<br />

implemented. In o<strong>the</strong>r words, <strong>the</strong> ECB would have to abandon its insistence th<strong>at</strong> even<br />

discussion of monetary policy by such o<strong>the</strong>r bodies…is an infringement on its<br />

independence (Martin, 2005, p. 8).<br />

Martin suggests this could be done without tre<strong>at</strong>y revision. All th<strong>at</strong> is required is for <strong>the</strong> ECB to<br />

change its policy orient<strong>at</strong>ion and oper<strong>at</strong>ing mode. Unfortun<strong>at</strong>ely, he doesn’t hold out much hope<br />

th<strong>at</strong> this will occur in <strong>the</strong> near future.<br />

<strong>Be</strong>gg and Schelkle suggest th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong>re is an effective middle ground based on prevention<br />

and co-ordin<strong>at</strong>ion.<br />

• There has to be a supran<strong>at</strong>ional body in which policy is formul<strong>at</strong>ed in a transparent<br />

manner. For this task, a more open Eurogroup is <strong>the</strong>ir body of choice.<br />

17

• There should be clear parameters for each Member St<strong>at</strong>e’s fiscal policy against which its<br />

record can be judged.<br />

• There need to be channels through which n<strong>at</strong>ional finance ministers can be held to<br />

account when <strong>the</strong>y make (or break) such commitments.<br />

• There should be a political price to pay for Member St<strong>at</strong>es th<strong>at</strong> breach agreed policies<br />

without good, economically defensible, reasons.<br />

There are obvious concerns with <strong>the</strong> effectiveness of <strong>Be</strong>gg and Schelkle’s proposed Eurogroup<br />

holding its finance ministers accountable. Their response is th<strong>at</strong><br />

Explicit political sanctions <strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> EU level, such as losing <strong>the</strong> right to vote on euro<br />

m<strong>at</strong>ters in Ecofin, might help to reinforce <strong>the</strong>se commitments, but <strong>the</strong> main sanction<br />

should be expected from <strong>the</strong> perception of failure in domestic politics (<strong>Be</strong>gg and<br />

Schelkle, 2005, p. 1055).<br />

In examining <strong>the</strong> behavior of larger member st<strong>at</strong>es compared to th<strong>at</strong> of smaller member<br />

st<strong>at</strong>es, Buti and Pench agreed with F<strong>at</strong>as, von Hagen, Hallett, Strauch, and Sibert in calling for<br />

gre<strong>at</strong>er flexibility. However, <strong>the</strong>y were equally as concerned as to <strong>the</strong> neg<strong>at</strong>ive results of gre<strong>at</strong>er<br />

flexibility without <strong>the</strong> ability to enforce <strong>the</strong> SGP.<br />

For any reform of <strong>the</strong> Pact to be credible, Member St<strong>at</strong>es, especially <strong>the</strong> larger ones, need<br />

to exhibit gre<strong>at</strong>er willingness to subordin<strong>at</strong>e short-term political gains to <strong>the</strong> long-term<br />

common good of protecting <strong>the</strong> monetary union from <strong>the</strong> risk of financial<br />

unsustainability. A powerful signal in this direction would be for <strong>the</strong> Member St<strong>at</strong>es<br />

against which an EDP is being initi<strong>at</strong>ed, to agree to abstain from voting <strong>at</strong> any step of <strong>the</strong><br />

procedure concerning any Member St<strong>at</strong>e. A self-denying ordinance of this kind,<br />

18

especially on <strong>the</strong> part of <strong>the</strong> largest Member St<strong>at</strong>es, would speak louder than a thousand<br />

Council communiqués on <strong>the</strong> Pact (Buti and Pench, 2005, p. 1032).<br />

The EU Responds<br />

Nearly two years after issuing its Streng<strong>the</strong>ning <strong>the</strong> Coordin<strong>at</strong>ion of Budgetary Policies, <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>European</strong> Commission, on September 3, 2004, issued its upd<strong>at</strong>ed proposals to improve <strong>the</strong> SGP.<br />

The main points of <strong>the</strong> Commission’s proposals were:<br />

• Current limits on public deficit and public debt would remain unchanged, but more<br />

emphasis would be placed on public debt and <strong>the</strong> viability of public finances in <strong>the</strong><br />

medium and long-term, taking into account retirement financing and growth potential.<br />

• Gre<strong>at</strong>er allowance would be made for country-specific circumstances in defining <strong>the</strong><br />

medium-term objectives of close to balance or in surplus budgets. The higher <strong>the</strong> debt<br />

level, <strong>the</strong> stricter <strong>the</strong> medium-term budget objective.<br />

• Consider<strong>at</strong>ion would be given to economic circumstances and developments in <strong>the</strong><br />

implement<strong>at</strong>ion of <strong>the</strong> EDP, used to prelude sanction in <strong>the</strong> case of a deficit in excess of<br />

<strong>the</strong> 3 percent of GDP reference value.<br />

• Countries th<strong>at</strong> experience prolonged periods of weak growth could invoke an<br />

exceptional circumstances clause to avoid an EDP, whereas currently this clause applies<br />

only to instances of neg<strong>at</strong>ive growth, or recession.<br />

• An extended EDP would allow more time between <strong>the</strong> different stages to tailor <strong>the</strong><br />

procedure to each country. Such an approach would avoid <strong>the</strong> pitfalls of overly strict<br />

adjustments.<br />

• Budgetary surveillance should ensure <strong>the</strong> achievement of surpluses in good times to<br />

cre<strong>at</strong>e sufficient room for dealing with economic slowdowns.<br />

19

The Commission’s proposals were forwarded to ECOFIN which met in February 2005 in<br />

an effort to reach agreement prior to <strong>the</strong> March summit of <strong>the</strong> <strong>European</strong> Council. Perhaps not<br />

surprisingly, <strong>the</strong> biggest sticking point evolved between <strong>the</strong> larger member st<strong>at</strong>es which wanted<br />

gre<strong>at</strong>er flexibility while <strong>the</strong> smaller member st<strong>at</strong>es wanted <strong>the</strong> existing budgetary discipline to be<br />

upheld. For example, Hans Eichler, Germany’s finance minister, proposed th<strong>at</strong> member st<strong>at</strong>es<br />

breaching <strong>the</strong> 3 percent reference value be spared disciplinary measures unless <strong>the</strong>y had<br />

committed serious policy errors.<br />

Eichler’s boss, Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder, had called for gre<strong>at</strong>er n<strong>at</strong>ional sovereignty<br />

over economic policy and a diminished role for <strong>the</strong> Commission. This was summarily rejected<br />

by Karl-Heinz Grasser, Austria’s foreign minister, as well as, interestingly enough, by <strong>the</strong><br />

Bundesbank, Germany’s central bank, which indic<strong>at</strong>ed th<strong>at</strong> higher interest r<strong>at</strong>es for <strong>the</strong> euro-zone<br />

were possible if member st<strong>at</strong>es abandoned <strong>the</strong> fiscal discipline required under <strong>the</strong> SGP.<br />

The final step in <strong>the</strong> reform process fell to <strong>the</strong> <strong>European</strong> Council meeting in Brussels in<br />

March 2005. The Council acknowledged th<strong>at</strong> in effect, <strong>the</strong> SGP was broken by st<strong>at</strong>ing th<strong>at</strong> “<strong>the</strong><br />

reform aims <strong>at</strong> better responding to <strong>the</strong> shortcomings experienced so far through gre<strong>at</strong>er<br />

emphasis to economic developments and an increased focus on safeguarding <strong>the</strong> sustainability of<br />

public finances” (<strong>European</strong> Council, 2005, p. 22). The report went on to suggest five areas ripe<br />

for improvement:<br />

• Enhance <strong>the</strong> economic r<strong>at</strong>ionale of <strong>the</strong> budgetary rules to improve <strong>the</strong>ir credibility and<br />

ownership.<br />

• Improve ‘ownership’ by n<strong>at</strong>ional policy makers.<br />

• Use more effectively periods when economies are growing above trend for budgetary<br />

consolid<strong>at</strong>ion in order to avoid pro-cyclical policies.<br />

20

• Take better account in Council recommend<strong>at</strong>ions of periods when economies are growing<br />

below trend.<br />

• Give sufficient <strong>at</strong>tention in <strong>the</strong> surveillance of budgetary positions to debt and<br />

sustainability. (<strong>European</strong> Council, 2005, p. 23).<br />

The document adopted by <strong>the</strong> Council includes many terms th<strong>at</strong> essentially support <strong>the</strong><br />

recommend<strong>at</strong>ions of <strong>the</strong> Commission while indic<strong>at</strong>ing th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong>re is no intention to scrap <strong>the</strong> SGP.<br />

For example, <strong>the</strong>y intend to ‘keep changes to a minimum’ while ‘streng<strong>the</strong>ning n<strong>at</strong>ional<br />

ownership of <strong>the</strong> fiscal framework’; promoting ‘cooper<strong>at</strong>ion and communic<strong>at</strong>ion’; ‘improving<br />

peer support and applying peer pressure’; suggesting th<strong>at</strong> ‘n<strong>at</strong>ional budgetary rules should be<br />

complementary’, while ‘increasing <strong>the</strong> focus on debt and sustainability’.<br />

A final quote from <strong>the</strong> document is perhaps a good indic<strong>at</strong>ion of <strong>the</strong> Council’s position.<br />

The excessive deficit procedure should remain simple, transparent and equitable.<br />

Never<strong>the</strong>less, <strong>the</strong> experience of recent years shows possible scope for improvement in its<br />

implement<strong>at</strong>ion. The guiding principle for <strong>the</strong> applic<strong>at</strong>ion of <strong>the</strong> procedure is <strong>the</strong> prompt<br />

correction of an excessive deficit. The Council underlines th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> purpose of <strong>the</strong><br />

excessive deficit procedure is to assist r<strong>at</strong>her than to punish, and <strong>the</strong>refore to provide<br />

incentives for Member St<strong>at</strong>es to pursue budgetary discipline, through enhanced<br />

surveillance, peer support and peer pressure. (<strong>European</strong> Council, 2005, p. 31).<br />

With nothing more than a cursory view of this document it is obvious th<strong>at</strong> nothing radical<br />

was agreed to th<strong>at</strong> would significantly alter or improve <strong>the</strong> SGP. Buti and Pench’s reference to a<br />

thousand Council communiqués jumps to mind. <strong>Is</strong> it any wonder <strong>the</strong>n th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> media and general<br />

public responded to this ‘reform’ with a big yawn and complete indifference. Granted, <strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

time, <strong>the</strong> Council was far more concerned with <strong>the</strong> upcoming referendums in France and <strong>the</strong><br />

21

Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands, which ultim<strong>at</strong>ely doomed <strong>the</strong> Constitution. Again, it is probably not too out-of-line<br />

to suggest th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> Council’s rel<strong>at</strong>ive inaction to reform <strong>the</strong> SGP contributed to rejection of <strong>the</strong><br />

Constitution in <strong>the</strong> Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands. The inaction merely reinforced <strong>the</strong> perception th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> larger<br />

member st<strong>at</strong>es can viol<strong>at</strong>e commitments with nothing more than a slap on <strong>the</strong> wrist.<br />

Conclusion<br />

In a paper presented <strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> EUSA biennial conference in Austin, a week after <strong>the</strong> Council<br />

met in Brussels, P<strong>at</strong>rick Crowley asked whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> SGP was ‘bad economies and/or <strong>the</strong> politics<br />

of least resistance’. His conclusion was th<strong>at</strong> it was both. He concludes with <strong>the</strong> following:<br />

The SGP currently contains bad economics, but also <strong>the</strong>se contents were arrived <strong>at</strong> by <strong>the</strong><br />

politics of least resistance. If <strong>the</strong> SGP is to contain good economics, <strong>the</strong>n choosing a pact<br />

on <strong>the</strong> basis of <strong>the</strong> politics of least resistance is simply not an option (Crowley, 2005, p.<br />

30).<br />

This seems a good summary st<strong>at</strong>ement of <strong>the</strong> current st<strong>at</strong>us of <strong>the</strong> SGP. No one argues<br />

th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> SGP is working well or even as it was originally envisioned. Views for fixing <strong>the</strong><br />

problem range <strong>the</strong> gambit from minor tinkering to scrapping <strong>the</strong> Pact entirely. Most of <strong>the</strong><br />

experts cited in this paper have called for more radical reforms than <strong>the</strong> Council undertook <strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Brussels summit. This fact does not bode well for <strong>the</strong> future success of <strong>the</strong> SGP, <strong>at</strong> least until <strong>the</strong><br />

time th<strong>at</strong> significant economic growth returns to <strong>the</strong> euro-zone countries.<br />

22

References<br />

<strong>Be</strong>gg, I. and Schelkle, W. (2004). <strong>Can</strong> Fiscal Policy Co-ordin<strong>at</strong>ion be Made to Work<br />

Effectively? Journal of Common Market Studies 42 (5), 1047-1055.<br />

Buti, M. and Pench, L. (2004). Why Do Large Countries Flout <strong>the</strong> Stability Pact? And Wh<strong>at</strong> <strong>Can</strong><br />

<strong>Be</strong> Done About <strong>It</strong>? Journal of Common Market Studies 42 (5), 1025-1032.<br />

Chang, M. (2005). Reforming <strong>the</strong> Stability and Growth Pact: Size and Influence in EMU<br />

Policymaking. Paper presented <strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> EUSA 9 th biennial conference in Austin, TX.<br />

Crowley, P. (2005). The Stability and Growth Pact: Bad Economics and/or <strong>the</strong> Politics of Least<br />

Resistance? Paper presented <strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> EUSA 9 th biennial conference in Austin, TX.<br />

Dinan, D. (2004). Europe Recast: A History of <strong>the</strong> <strong>European</strong> Union. Boulder, CO: Lynn Reinner<br />

Publishers.<br />

. (1999) Ever Closer Union: An Introduction to <strong>European</strong> Integr<strong>at</strong>ion. 2 nd ed. Boulder,<br />

CO: Lynn Reinner Publishers.<br />

Enderlein, H. (2004). Break it, Don’t Fix it! Journal of Common Market Studies 42 (5),<br />

1039-1046.<br />

EU Business (2004). EU commission proposals to reform Stability and Growth Pact.<br />

Retrieved September 10, 2004, from http://www.eubusiness.com<br />

EU Business (2005). EU <strong>at</strong> odds over reform to euro rules. Retrieved January 21, 2005, from<br />

http://www.eubusiness.com<br />

EU Business (2005). EU finance ministers struggle to agree on stability pact reform. Retrieved<br />

February 18, 2005, from http://www.eubusiness.com<br />

25

Europa (2005). Selected instruments taken from <strong>the</strong> Tre<strong>at</strong>ies. Retrieved July 13, 2005, from<br />

http://europa.eu.int/eur-lex/en/tre<strong>at</strong>ies/selected/livre223.html#anArt6<br />

Europa (2005). Excessive Deficit Procedure (EDP). Retrieved July 13, 2005, from<br />

http://europa.eu.int/comm/economy_finance/about/activities/sgp/edp_en.htm<br />

Europa (2005). The Stability and Growth Pact. Retrieved July 22, 2005, from<br />

http://europa.eu.int/comm/economy_finance/about/activities/sgp/sgp_en.htm<br />

<strong>European</strong> Commission (2003). Public Finances in EMU 2003. Director<strong>at</strong>e-General for Economic<br />

And Financial Affairs, Brussels.<br />

<strong>European</strong> Council (2005). Improving <strong>the</strong> implement<strong>at</strong>ion of <strong>the</strong> Stability and Growth Pact.<br />

Retrieved August 19, 2005, from<br />

http://ue.eu.int/euDocs/cms_D<strong>at</strong>a/docs/pressd<strong>at</strong>a/en/ec184335.pdf<br />

Eurost<strong>at</strong> (2002). Euro-zone government deficit <strong>at</strong> 1.4% of GDP and public debt <strong>at</strong> 69.2% of<br />

GDP. 116/2002 – 30 September 2002. Retrieved July 23, 2005, from<br />

http://epp.eurost<strong>at</strong>.cec.eu.int<br />

Eurost<strong>at</strong> (2004). Euro-zone government deficit <strong>at</strong> 2.7% of GDP and public debt <strong>at</strong> 70.4% of<br />

GDP. 38/2004 – 16 March 2004. Retrieved April 30, 2004, from<br />

http://epp.eurost<strong>at</strong>.cec.eu.int<br />

Eurost<strong>at</strong> (2005). Euro-zone and EU25 government deficit <strong>at</strong> 2.7% and 2.6% of GDP<br />

respectively. 39/2005 – 18 March 2005. Retrieved July 13, 2005, from<br />

http://eurost<strong>at</strong>.cec.eu.int<br />

F<strong>at</strong>as, A., von Hagen, J., Hallett, H., Strauch, R., and A. Sibert (2003). Stability and Growth in<br />

Europe: Towards a <strong>Be</strong>tter Pact. Centre for Economic Policy Research, London.<br />

Jabko, N. (2005). No Immedi<strong>at</strong>e De<strong>at</strong>h, but More Headaches to Come. EUSA Review 18 (1), 4-5.<br />

26

Martin, A. (2005). Blame <strong>the</strong> ECB, Not <strong>the</strong> Stability and Growth Pact. EUSA Review 18 (1), 7-8.<br />

Verdun, A. (2005). The Rise and Rise of <strong>the</strong> Stability and Growth Pact. EUSA Review 18 (1),<br />

1-4.<br />

27