sector skills plan for the health sector in south africa

sector skills plan for the health sector in south africa

sector skills plan for the health sector in south africa

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

SECTOR SKILLS PLAN FOR THE HEALTH SECTOR IN SOUTH AFRICA<br />

SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF HIGHER EDUCATION AND TRAINING<br />

BY THE HEALTH AND WELFARE SETA<br />

FINAL DRAFT<br />

FEBRUARY 2011

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................. x<br />

INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................................... x<br />

PROFILE OF THE HEALTH SECTOR ............................................................................................................. x<br />

FACTORS INFLUENCING THE HEALTH SECTOR LABOUR MARKET ........................................................... xii<br />

DEMAND FOR SKILLS ............................................................................................................................... xiv<br />

SUPPLY OF SKILLS .................................................................................................................................... xv<br />

SKILLS DEVELOPMENT PRIORITIES OF THE HWSETA ............................................................................. xvii<br />

1 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................... 1<br />

1.1 BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................................... 1<br />

1.1 PREPARATION OF THE SSP ............................................................................................................ 1<br />

1.2 STAKEHOLDER CONSULTATION .................................................................................................... 2<br />

1.3 LIMITATIONS ................................................................................................................................. 3<br />

1.4 OUTLINE OF THE SSP ..................................................................................................................... 3<br />

2 PROFILE OF THE SECTOR ....................................................................................................................... 4<br />

2.1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................. 4<br />

2.2 THE SOUTH AFRICAN HEALTH SYSTEM ......................................................................................... 4<br />

2.3 EMPLOYERS IN THE SECTOR .......................................................................................................... 6<br />

2.4 ORGANISATIONS IN THE SECTOR .................................................................................................. 6<br />

2.4.1 REGULATORS AND PROFESSIONAL BODIES .......................................................................... 6<br />

2.4.2 ACADEMIC AND RESEARCH INSTITUTIONS ........................................................................... 9<br />

2.4.3 EMPLOYER ORGANISATIONS............................................................................................... 11<br />

2.4.4 NON-GOVERNMENTAL ORGANISATIONS ........................................................................... 11<br />

2.4.5 PROFESSIONAL ASSOCIATIONS ........................................................................................... 12<br />

i

2.4.6 LABOUR UNIONS ................................................................................................................. 12<br />

2.5 PROFILE OF EMPLOYEES IN THE SECTOR .................................................................................... 13<br />

2.6 CONCLUSIONS ............................................................................................................................. 18<br />

3 FACTORS INFLUENCING THE HEALTH SECTOR LABOUR MARKET ....................................................... 20<br />

3.1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 20<br />

3.2 HEALTH SPENDING ...................................................................................................................... 20<br />

3.2.1 PUBLIC SECTOR SPENDING.................................................................................................. 21<br />

3.2.2 PRIVATE SECTOR SPENDING ............................................................................................... 22<br />

3.3 THE DEMAND FOR HEALTH SERVICES ......................................................................................... 23<br />

3.3.1 THE PUBLIC-PRIVATE DIVIDE ............................................................................................... 23<br />

3.3.2 THE DEMAND FOR PUBLIC HEALTH CARE ........................................................................... 24<br />

3.3.3 THE DEMAND FOR PRIVATE HEALTHCARE SERVICES .......................................................... 26<br />

3.4 THE MOBILITY OF LABOUR .......................................................................................................... 27<br />

3.5 ECONOMIC DOWNTURN ............................................................................................................. 27<br />

3.6 THE BURDEN OF DISEASE ............................................................................................................ 27<br />

3.7 HUMAN RESOURCES CHALLENGES ............................................................................................. 29<br />

3.8 MANAGEMENT OF THE HEALTH SYSTEM ................................................................................... 31<br />

3.9 THE REGULATORY ENVIRONMENT ............................................................................................. 32<br />

3.9.1 REGULATION OF QUANTITY AND DISTRIBUTION ................................................................ 32<br />

3.9.2 REGULATION OF QUALITY ................................................................................................... 33<br />

3.10 NATIONAL HEALTH POLICIES....................................................................................................... 33<br />

3.10.1 PRIMARY HEALTHCARE ....................................................................................................... 34<br />

3.10.2 COMMUNITY HEALTH WORKERS ........................................................................................ 34<br />

3.10.3 A NATIONAL HEALTH INSURANCE SYSTEM ......................................................................... 36<br />

3.10.4 HIV AND AIDS POLICIES ....................................................................................................... 38<br />

ii

3.10.5 STRATEGY TO FIGHT TUBERCULOSIS .................................................................................. 39<br />

3.10.6 MATERNAL AND CHILD HEALTH .......................................................................................... 39<br />

3.11 EMPLOYMENT EQUITY AND BEE ................................................................................................. 40<br />

3.12 VETERINARY SERVICES ................................................................................................................ 40<br />

3.13 CONCLUSION ............................................................................................................................... 41<br />

4 THE DEMAND FOR SKILLS.................................................................................................................... 43<br />

4.1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 43<br />

4.2 CURRENT EMPLOYMENT ............................................................................................................. 43<br />

4.2.1 POSITIONS IN THE PUBLIC SERVICE ..................................................................................... 43<br />

4.2.2 POSITIONS IN THE PRIVATE SECTOR ................................................................................... 44<br />

4.3 CURRENT SHORTAGES ................................................................................................................ 45<br />

4.3.1 VACANCY RATES .................................................................................................................. 45<br />

4.3.2 BENCHMARKING AND COMPARISONS ............................................................................... 48<br />

4.4 FUTURE DEMAND ....................................................................................................................... 49<br />

4.4.1 SKILLS DEVELOPMENT TARGETS SET BY THE NATIONAL DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH.......... 49<br />

4.5 FACTORS THAT IMPACT ON THE DEMAND FOR HEALTHCARE WORKERS .................................. 49<br />

4.5.1 HIV AND AIDS TREATMENT POLICIES .................................................................................. 49<br />

4.5.2 POLICIES TO CONTROL TUBERCULOSIS ............................................................................... 50<br />

4.5.3 MATERNAL, CHILD AND WOMEN’S HEALTH PROGRAMMES ............................................. 51<br />

4.5.4 MANAGEMENT OF HEALTH OPERATIONS AND PEOPLE ..................................................... 51<br />

4.5.5 EXPANSION OF THE PUBLIC HEALTH INFRASTRUCTURE ..................................................... 52<br />

4.5.6 SKILLS REQUIREMENTS FOR THE NHI .................................................................................. 52<br />

4.6 CONCLUSIONS ............................................................................................................................. 53<br />

5 THE SUPPLY OF SKILLS ......................................................................................................................... 55<br />

5.1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 55<br />

iii

5.2 THE SOUTH AFRICAN SECONDARY SCHOOL SYSTEM .................................................................. 55<br />

5.3 INSTITUTIONAL ARRANGEMENTS AND CAPACITY FOR THE TRAINING OF HEALTH WORKERS .. 59<br />

5.3.1 ACADEMIC COMPLEXES ...................................................................................................... 59<br />

5.3.2 PRIVATE HIGHER EDUCATION AND TRAINING INSTITUTIONS ............................................ 59<br />

5.3.3 PRIVATE FURTHER EDUCATION AND TRAINING INSTITUTIONS ......................................... 60<br />

5.3.4 PRIVATE HOSPITALS ............................................................................................................ 61<br />

5.3.5 CPD PROVISION ................................................................................................................... 62<br />

5.3.6 NON-PROFIT ORGANISATIONS ............................................................................................ 62<br />

5.4 PROFESSIONAL REGISTRATION ................................................................................................... 62<br />

5.4.1 REGISTRATIONS WITH THE HEALTH PROFESSIONS COUNCIL OF SOUTH AFRICA ............... 62<br />

5.4.2 REGISTRATIONS WITH THE SOUTH AFRICAN NURSING COUNCIL ...................................... 63<br />

5.4.3 REGISTRATIONS WITH THE SOUTH AFRICAN PHARMACY COUNCIL ................................... 65<br />

5.4.4 REGISTRATIONS WITH THE ALLIED HEALTH PROFESSIONS COUNCIL OF SOUTH AFRICA ... 65<br />

5.4.5 REGISTRATIONS WITH THE SOUTH AFRICAN VETERINARY COUNCIL ................................. 66<br />

5.5 THE SUPPLY OF NEW GRADUATES BY THE HIGHER EDUCATION SYSTEM .................................. 66<br />

5.5.1 HIGHER EDUCATION AND TRAINING .................................................................................. 66<br />

5.6 THE SUPPLY OF NEW ENTRANTS THROUGH NURSING COLLEGES.............................................. 68<br />

5.7 THE ROLE OF THE HWSETA IN THE SUPPLY OF SKILLS ................................................................ 68<br />

5.7.1 THE REGISTRATION OF QUALIFICATIONS AND LEARNERSHIPS .......................................... 68<br />

5.7.2 LEARNERS WHO QUALIFIED ON LEARNERSHIPS ................................................................. 69<br />

5.7.3 INTERNSHIPS ....................................................................................................................... 71<br />

5.7.4 SKILLS PROGRAMMES ......................................................................................................... 71<br />

5.7.5 ADULT BASIC EDUCATION AND TRAINING (ABET).............................................................. 71<br />

5.7.6 RECOGNITION OF PRIOR LEARNING ................................................................................... 72<br />

5.7.7 SKILLS DEVELOPMENT SUPPORT TO SMALL ENTERPRISES ................................................. 72<br />

iv

5.7.8 EXPANDED PUBLIC WORKS PROGRAMME .......................................................................... 72<br />

5.8 FACTORS INFLUENCING THE SUPPLY OF SKILLS .......................................................................... 73<br />

5.8.1 GOVERNMENT STRATEGIES AND POLICY INTERVENTIONS ................................................ 73<br />

5.8.2 MANAGEMENT OF THE PUBLIC SECTOR HEALTH FACILITIES .............................................. 75<br />

5.8.3 MIGRATION OF PROFESSIONALS ........................................................................................ 76<br />

5.8.4 THE IMPACT OF HIVAND AIDS............................................................................................. 77<br />

5.8.5 RECRUITMENT OF FOREIGN HEALTH WORKERS ................................................................. 77<br />

5.8.6 SOCIO-ECONOMIC REALITIES OF POTENTIAL LEARNERS .................................................... 78<br />

5.9 CONCLUSIONS ............................................................................................................................. 78<br />

6 SKILLS DEVELOPMENT PRIORITIES OF THE HWSETA .......................................................................... 80<br />

6.1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 80<br />

6.2 CONTRIBUTION TO GOVERNMENT’S MTSF OBJECTIVES ............................................................ 80<br />

6.3 SECTORAL CONTRIBUTION TO STRATEGIC AREAS OF FOCUS FOR NSDS III ................................ 80<br />

6.3.1 EQUITY IMPACT ................................................................................................................... 80<br />

6.3.2 CODE OF DECENT CONDUCT ............................................................................................... 81<br />

6.3.3 LEARNING PROGRAMMES FOR DECENT WORK .................................................................. 81<br />

6.3.4 PIVOTAL OCCUPATIONAL PROGRAMMES .......................................................................... 82<br />

6.3.5 SKILLS PROGRAMMES AND OTHER NON-ACCREDITED SHORT COURSES .......................... 82<br />

6.3.6 PROGRAMMES THAT BUILD THE ACADEMIC PROFESSION AND ENGENDER INNOVATION<br />

83<br />

6.3.7 STRENGTHEN OUR OWN CAPACITY AND THAT OF OUR DELIVERY PARTNERS .................. 83<br />

6.4 CONCLUSIONS ............................................................................................................................. 83<br />

v

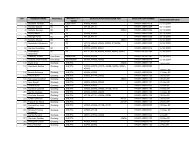

LIST OF TABLES<br />

Table 2-1 Total employment <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> private <strong>sector</strong> and <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Public Service accord<strong>in</strong>g to occupational<br />

category ...................................................................................................................................................... 15<br />

Table 2-2 Estimates of employment <strong>in</strong> selected occupations .................................................................... 15<br />

Table 2-3 Total employment <strong>in</strong> private and public <strong>health</strong> accord<strong>in</strong>g to population group ........................ 16<br />

Table 2-4 Total employment <strong>in</strong> private and public <strong>health</strong> accord<strong>in</strong>g to gender ........................................ 17<br />

Table 2-5 Age profile of key professionals <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Public Service ................................................................ 18<br />

Table 2-6 Age profile of medical practitioners (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g medical specialists) <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> private <strong>sector</strong> ......... 18<br />

Table 3-1 Health expenditure <strong>in</strong> public and private <strong>sector</strong>s: 2007 -2010 .................................................. 21<br />

Table 3-2 Use of public and private <strong>sector</strong> facilities accord<strong>in</strong>g to medical <strong>in</strong>surance (of those who were<br />

ill/<strong>in</strong>jured or sought care): 2007 ................................................................................................................. 24<br />

Table 3-3 Primary <strong>health</strong>care visits per prov<strong>in</strong>ce: 2008/09 ....................................................................... 25<br />

Table 3-4 Primary <strong>health</strong>care workload per prov<strong>in</strong>ce: 2008/09 ................................................................ 25<br />

Table 3-5 Key resources per 100 000 population <strong>in</strong> public and private <strong>sector</strong>s: 2009 ............................... 29<br />

Table 3-6 Distribution of <strong>health</strong> professionals per 100000 population <strong>in</strong> public <strong>sector</strong>: 2008 .................. 30<br />

Table 4-1 Total number of positions <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> private <strong>health</strong> organisations .................................................. 44<br />

Table 4-2 Total professional positions <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> private <strong>health</strong> organisations ................................................ 45<br />

Table 4-3 Vacancy rates <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> National and prov<strong>in</strong>cial <strong>health</strong> departments <strong>in</strong> selected occupation: 31<br />

March 2010 ................................................................................................................................................. 46<br />

Table 4-4 Scarce <strong>skills</strong> <strong>in</strong> private and public <strong>health</strong> accord<strong>in</strong>g to occupational category ........................... 47<br />

Table 4-5 Public <strong>sector</strong> staff needs to meet <strong>in</strong>ternational <strong>in</strong>-hospital benchmarks ................................... 48<br />

Table 5-1 Grade 12 statistics – ma<strong>the</strong>matics, physical sciences and life sciences: 2008 ........................... 56<br />

Table 5-2 Grade 12 statistics – ma<strong>the</strong>matics: 1999-2007 .......................................................................... 56<br />

Table 5-3 Grade 12 statistics – physical science: 1999-2007 ...................................................................... 57<br />

Table 5-4 Grade 12 statistics – biology: 1999-2007 .................................................................................... 58<br />

Table 5-5 Number of professionals registered with <strong>the</strong> HPCSA as at 31 December of 2000 to 2009<br />

(selected professions)* ............................................................................................................................... 64<br />

vi

Table 5-6 Number of nurses registered with <strong>the</strong> SANC: 2000 to 2009 ...................................................... 64<br />

Table 5-7 Number of registrations with <strong>the</strong> SAPC: 2010 ............................................................................ 65<br />

Table 5-8 Total registrations with <strong>the</strong> AHPCSA: 2010 ................................................................................. 65<br />

Table 5-9 Number of registrations with <strong>the</strong> SAVC: 2010 .......................................................................... 66<br />

Table 5-10 Number of <strong>health</strong>-related qualifications awarded by <strong>the</strong> public higher education <strong>sector</strong>: 1999<br />

to 2008 ........................................................................................................................................................ 67<br />

Table 5-11 Number of graduates at nurs<strong>in</strong>g colleges: 2000 to 2009 ......................................................... 68<br />

Table 5-12 FET level qualifications registered by HWSETA on <strong>the</strong> NQF ..................................................... 68<br />

Table 5-13 HWSETA learnerships at FET level ............................................................................................ 69<br />

Table 5-14 Number of learners who completed learnerships <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong> <strong>sector</strong>: 2002 to 2010 ............ 70<br />

LIST OF FIGURES<br />

Figure 2-1 The South African <strong>health</strong> system ................................................................................................ 4<br />

Figure 2-3 Professionals by population group <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong> <strong>sector</strong> ............................................................ 17<br />

Figure 5-1 Comparison of output <strong>in</strong> basic nurs<strong>in</strong>g tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g between public and private <strong>sector</strong>s: 2007 -<br />

2009 ............................................................................................................................................................ 61<br />

APPENDIX<br />

APPENDIX A SCARCE SKILLS LIST – PRIVATE ORGANISATIONS AND PUBLIC SERVICE DEPARTMENTS ....... 93<br />

APPENDIX B HWSETA STRATEGIC BUSINESS PLAN 2011-2016……………...……………………………………………….96<br />

vii

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS<br />

ABET<br />

AgriSETA<br />

AHPCSA<br />

AIDS<br />

ARC<br />

ART<br />

ATR<br />

CBO<br />

CCWMPF<br />

CHW<br />

CPD<br />

DBSA<br />

DENOSA<br />

DG<br />

DHET<br />

DoA<br />

DoH<br />

DoSD<br />

DPSA<br />

EMIS<br />

FET<br />

HASA<br />

HCBC<br />

HEI<br />

HEMIS<br />

HEQC<br />

HET<br />

HIV<br />

HOSPERSA<br />

HPCSA<br />

HSRC<br />

HWSETA<br />

INSETA<br />

ITHPCSA<br />

LGSETA<br />

MDG<br />

MDR TB<br />

MoU<br />

MRC<br />

MTSF<br />

NEHAWU<br />

NGO<br />

NHA<br />

Adult Basic Education and Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g<br />

Agricultural Sector Education and Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g Authority<br />

Allied Health Professions Council of South Africa<br />

Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome<br />

Agricultural Research Council<br />

Anti-Retroviral Therapy<br />

Annual Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g Reports<br />

Community-Based Organisation<br />

Community Care Worker Management Policy Framework<br />

Community Health Worker<br />

Cont<strong>in</strong>uous Professional Development<br />

Development Bank of South Africa<br />

Democratic Nurs<strong>in</strong>g Organisation of South Africa<br />

Director-General<br />

Department of Higher Education and Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g<br />

Department of Agriculture<br />

Department of Health<br />

Department of Social Development<br />

Department of Public Service and Adm<strong>in</strong>istration<br />

Education Management In<strong>for</strong>mation System<br />

Fur<strong>the</strong>r Education and Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g<br />

Hospital Association of South Africa<br />

Home-Community-Based Care<br />

Higher Education Institution<br />

Higher Education Management In<strong>for</strong>mation System<br />

Higher Education Quality Committee<br />

Higher Education and Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g<br />

Human Immune Virus<br />

Health and O<strong>the</strong>r Service Personnel Trade Union of South Africa<br />

Health Professions Council of South Africa<br />

Human Sciences Research Council<br />

Health and Welfare Sector Education and Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g Authority<br />

Sector Education and Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g Authority<br />

Interim Traditional Health Practitioners Council of South Africa<br />

Local Government SETA<br />

Millennium Development Goals<br />

Multiple Drug Resistant Tuberculosis<br />

Memorandum of Understand<strong>in</strong>g<br />

South African Medical Research Council<br />

Medium Term Strategic Framework<br />

National Education Health and Allied Workers Union<br />

Non-governmental Organisation<br />

National Health Act<br />

viii

NHI<br />

NHLS<br />

NPO<br />

NQF<br />

NSF<br />

NSDS<br />

OFO<br />

OVI<br />

PHC<br />

PSA<br />

PSETA<br />

QMS<br />

RPL<br />

SADA<br />

SADNU<br />

SADTC<br />

SAMA<br />

SANC<br />

SANDF<br />

SAPC<br />

SARS<br />

SAVC<br />

SDA<br />

SDL<br />

SETA<br />

SSP<br />

TB<br />

UMALUSI<br />

W&RSETA<br />

WHO<br />

WSP<br />

XDR TB<br />

National Health Insurance<br />

National Health Laboratory Service<br />

Non-Profit Organisation<br />

National Qualifications Framework<br />

National Skills Fund<br />

National Skills Development Strategy<br />

Organis<strong>in</strong>g Framework <strong>for</strong> Occupations<br />

Onderstepoort Veter<strong>in</strong>ary Institute<br />

Primary Healthcare<br />

Public Servants Association<br />

Public Service SETA<br />

Quality Management System<br />

Recognition of Prior Learn<strong>in</strong>g<br />

South African Dental Association<br />

South African Democratic Nurses Union<br />

South African Dental Technicians Council<br />

South African Medical Association<br />

South African Nurs<strong>in</strong>g Council<br />

South African National Defence Force<br />

South African Pharmacy Council<br />

South African Revenue Service<br />

South African Veter<strong>in</strong>ary Council<br />

Skills Development Act<br />

Skills Development Levy<br />

Sector Education and Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g Authority<br />

Sector Skills Plan<br />

Tuberculosis<br />

Council <strong>for</strong> Quality Assurance <strong>in</strong> General and Fur<strong>the</strong>r Education and Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g<br />

Wholesale and Retail SETA<br />

World Health Organization<br />

Workplace Skills Plan<br />

Extreme Drug Resistant Tuberculosis<br />

ix

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

The Health and Welfare Sector Education and Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g Authority (HWSETA) prepared this Sector Skills<br />

Plan (SSP) <strong>in</strong> accordance with <strong>the</strong> requirements set out by <strong>the</strong> Department of Higher Education and<br />

Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g (DHET) <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Draft National Skills Development Strategy (NSDS) III framework document. In<br />

anticipation of <strong>the</strong> proposed restructur<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>the</strong> HWSETA <strong>in</strong>to two SETAs, one <strong>for</strong> <strong>health</strong> and a separate<br />

welfare SETA, this document deals only with <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong> <strong>sector</strong>.<br />

Various data sources were used to prepare <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong> <strong>sector</strong> analysis and to construct a profile of <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>sector</strong>. Data from <strong>the</strong> workplace <strong>skills</strong> <strong>plan</strong>s (WSPs) submitted by private <strong>sector</strong> employers to <strong>the</strong><br />

HWSETA were comb<strong>in</strong>ed with data extracted from such <strong>plan</strong>s submitted by public <strong>sector</strong> employers to<br />

<strong>the</strong> PSETA. In<strong>for</strong>mation on employment by <strong>the</strong> national and prov<strong>in</strong>cial <strong>health</strong> departments was<br />

obta<strong>in</strong>ed from <strong>the</strong> PERSAL system. Data extracted from <strong>the</strong> registers of <strong>health</strong> professionals and paraprofessionals<br />

ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed by <strong>the</strong> statutory councils were analysed. In<strong>for</strong>mation from <strong>the</strong> Education<br />

Management In<strong>for</strong>mation System (EMIS) and <strong>the</strong> Higher Education Management In<strong>for</strong>mation System<br />

(HEMIS) kept by <strong>the</strong> Department of Basic Education and DHET respectively was also used <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

preparation of <strong>the</strong> SSP. MEDpages, a private database of <strong>health</strong> service providers <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> private <strong>sector</strong>,<br />

was comb<strong>in</strong>ed with <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r employment databases <strong>in</strong> order to obta<strong>in</strong> a comprehensive picture of<br />

employment <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> private <strong>health</strong>care <strong>sector</strong>. Extensive desktop research was conducted on various<br />

aspects of <strong>the</strong> South African <strong>health</strong> <strong>sector</strong> and <strong>in</strong>corporated <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> SSP. The HWSETA also <strong>in</strong>vited<br />

<strong>in</strong>puts to <strong>the</strong> SSP via an electronic survey. This feedback, toge<strong>the</strong>r with <strong>in</strong>puts made at seven<br />

stakeholder workshops and contributions from <strong>in</strong>terviews held with five key role-players <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong><br />

<strong>sector</strong>, was also used <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> preparation of <strong>the</strong> SSP.<br />

Dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> preparation of this SSP, <strong>the</strong> HWSETA encountered significant difficulties with <strong>the</strong> lack of data,<br />

gaps <strong>in</strong> and quality of <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation, as well as <strong>in</strong>consistencies <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> data of <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong> <strong>sector</strong>’s human<br />

resources. This hampers demand analysis, projections on future needs and <strong>plan</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g. In <strong>the</strong> recent past,<br />

several researchers have had similar experiences. It is vital that <strong>the</strong>se <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation gaps be addressed<br />

jo<strong>in</strong>tly by <strong>the</strong> major role-players, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> national and prov<strong>in</strong>cial <strong>health</strong> departments, professional<br />

councils, higher education authorities, tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>stitutions, <strong>the</strong> HWSETA and <strong>the</strong> private <strong>sector</strong>.<br />

PROFILE OF THE HEALTH SECTOR<br />

The <strong>sector</strong> served by <strong>the</strong> HWSETA <strong>for</strong>ms part of <strong>the</strong> South African Health System, which spans <strong>the</strong><br />

economic <strong>sector</strong>s <strong>for</strong> human and animal <strong>health</strong>.<br />

However, not all <strong>the</strong> entities <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> South African Health System <strong>for</strong>m part of <strong>the</strong> HWSETA <strong>sector</strong> and<br />

<strong>the</strong>re is considerable overlap with several o<strong>the</strong>r SETAs, <strong>the</strong> national and prov<strong>in</strong>cial departments of<br />

<strong>health</strong> submit WSPs to <strong>the</strong> Public Service SETA (PSETA), <strong>for</strong> example. The economic activities that fall<br />

with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> scope of <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong> component of <strong>the</strong> HWSETA range from all <strong>health</strong>care facilities and<br />

services, pharmaceutical services and <strong>the</strong> distribution of medic<strong>in</strong>e, medical research, non-governmental<br />

x

organisations, to veter<strong>in</strong>ary services. In <strong>the</strong> 2009/2010 f<strong>in</strong>ancial year a total of 4 321 organisations paid<br />

<strong>skills</strong> development levies to <strong>the</strong> HWSETA.<br />

In 2010, an estimated 460 000 people are employed <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong> <strong>sector</strong>, of which 179 000 (39%) are<br />

employed <strong>in</strong> private <strong>health</strong> and 281 000 (61%) <strong>in</strong> public <strong>health</strong> departments.<br />

A large portion of <strong>the</strong> workers <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong> <strong>sector</strong> are registered with statutory professional councils<br />

that regulate <strong>the</strong> various professions. These councils are <strong>the</strong> Health Professions Council of South Africa<br />

(HPCSA), <strong>the</strong> South African Nurs<strong>in</strong>g Council (SANC), <strong>the</strong> South African Pharmacy Council (SAPC), <strong>the</strong><br />

Allied Health Professions Council of South Africa (AHPCSA) and <strong>the</strong> South African Dental Technicians<br />

Council (SADTC). Members of <strong>the</strong> veter<strong>in</strong>ary and para-veter<strong>in</strong>ary professions are registered with <strong>the</strong><br />

South African Veter<strong>in</strong>ary Council (SAVC) and practitioners us<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>digenous African <strong>health</strong>care<br />

techniques and medic<strong>in</strong>es will soon be required to register with <strong>the</strong> Interim Traditional Health<br />

Practitioners Council of South Africa (ITHPCSA). In many <strong>in</strong>stances <strong>the</strong>se councils determ<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong> scope<br />

of practice <strong>for</strong> various <strong>health</strong> professions and en<strong>for</strong>ce rules of ethical and professional conduct. The<br />

professional councils are actively <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> <strong>skills</strong> development through <strong>the</strong> sett<strong>in</strong>g and controll<strong>in</strong>g of<br />

standards <strong>for</strong> education and tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, <strong>the</strong> registration of professionals, and cont<strong>in</strong>uous professional<br />

development.<br />

In both <strong>the</strong> Public Service and <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> private <strong>sector</strong> managers constitute approximately 4% of total<br />

employment. Almost half (47%) of employees <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> private <strong>sector</strong> are employed as professionals and<br />

28% <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Public Service. Professionals <strong>in</strong>clude medical and dental practitioners, registered nurses,<br />

pharmacists, and o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>health</strong>-related occupations such as occupational <strong>the</strong>rapists and psychologists.<br />

Community and personal service workers <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Public Service constitute 42% of total employment. This<br />

category ma<strong>in</strong>ly comprises enrolled and auxiliary nurses, emergency service and ambulance workers and<br />

food and auxiliary hospital workers and aides.<br />

In 2010, <strong>the</strong> majority (87%) of <strong>the</strong> people work<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>sector</strong> are black, while white workers constitute<br />

only 13% of <strong>the</strong> total work<strong>for</strong>ce. Most (63%) of <strong>the</strong> professionals employed <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> total <strong>sector</strong> are<br />

African, 21% are white, 9% coloured and 7% are Indian. Among community workers and personal<br />

service workers, 80% <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> private <strong>sector</strong> and 86% <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Public Service are Africans. Women constitute<br />

75% of <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong> work<strong>for</strong>ce and <strong>the</strong> professionals <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> public <strong>sector</strong>.<br />

The majority of medical doctors/practitioners (80%), dentists (77%) and pharmacists (74%) <strong>in</strong> public<br />

<strong>health</strong> are younger than 45. More than 50% of professional nurses are 45 and older. Of <strong>the</strong> medical<br />

practitioners and specialists <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> private <strong>sector</strong>, 42% are younger than 45.<br />

A number of <strong>in</strong>stitutions conduct<strong>in</strong>g research <strong>in</strong> human and animal <strong>health</strong> and <strong>the</strong> socio-economic<br />

impact of disease play a prom<strong>in</strong>ent role <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong> <strong>sector</strong>. In addition to <strong>the</strong>ir research activities, <strong>the</strong><br />

Medical Research Council (MRC), National Health Laboratory Service (NHLS), Human Sciences Research<br />

Council (HSRC) and <strong>the</strong> Onderstepoort Veter<strong>in</strong>ary Institute (OVI) are specifically mandated to advance<br />

<strong>the</strong> tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g and development of researchers, <strong>health</strong> professionals and technicians <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong> <strong>sector</strong>.<br />

xi

Health professionals and practitioners are organised <strong>in</strong> numerous voluntary organisations that generally<br />

promote <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terests of specific fields of medical practice and <strong>the</strong>ir members, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

educational and economic <strong>in</strong>terests. The Hospital Association of South Africa (HASA) represents 90% of<br />

<strong>the</strong> private hospital groups and is a lead<strong>in</strong>g employer organisation <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>sector</strong>. Labour and trade<br />

unions are well organised and mobilised with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong> <strong>sector</strong>. Trade unions play a <strong>for</strong>mative role <strong>in</strong><br />

shap<strong>in</strong>g labour market policies, labour relations practices and human resources management <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>sector</strong>.<br />

Non-governmental organisations play an essential part <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> delivery of <strong>health</strong>care to disadvantaged<br />

and marg<strong>in</strong>alised communities, even though <strong>the</strong>y fall outside <strong>the</strong> <strong>sector</strong>’s <strong>for</strong>mal structures.<br />

FACTORS INFLUENCING THE HEALTH SECTOR LABOUR MARKET<br />

South Africans access medical care ei<strong>the</strong>r through <strong>the</strong> public <strong>health</strong> system or through <strong>the</strong>ir own <strong>health</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>surance arrangements with medical schemes, or <strong>in</strong>cur out-of-pocket expenses. More than 41 million<br />

people rely on <strong>the</strong> public <strong>health</strong> system and 7.9 million people are covered by medical <strong>in</strong>surance. About<br />

28% of <strong>the</strong> un<strong>in</strong>sured population consult private practitioners, but use public hospital services. An<br />

estimated 64% to 68% of <strong>the</strong> population is entirely dependent on public <strong>sector</strong> care.<br />

Many <strong>in</strong>equalities are entrenched <strong>in</strong> South Africa’s public-private <strong>health</strong>care mix. In 2009, <strong>the</strong> per capita<br />

expenditure on <strong>health</strong>care <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> public <strong>sector</strong> was about R2,058, but it was six times higher <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

private <strong>sector</strong>. In 2010 total <strong>health</strong>care expenditure <strong>in</strong> South Africa was estimated to be above R227<br />

billion, with more than 53% of this attributable to private <strong>sector</strong> spend<strong>in</strong>g. Significantly higher numbers<br />

of <strong>health</strong> professionals serve <strong>health</strong>care users <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> private <strong>sector</strong> than <strong>the</strong> public <strong>sector</strong> population.<br />

For example, more than three times <strong>the</strong> number of doctors and seven times <strong>the</strong> number of medical<br />

specialists are available to private <strong>sector</strong> users, compared to <strong>the</strong> public <strong>sector</strong>. The ratio of nurses per<br />

private <strong>sector</strong> population is almost double that of <strong>the</strong> public <strong>sector</strong>.<br />

From 1995 onwards <strong>the</strong> public <strong>sector</strong> moved from a hospital-based approach to a primary <strong>health</strong>care<br />

(PHC) approach. This is also reflected <strong>in</strong> public <strong>sector</strong> spend<strong>in</strong>g, with about 41% of public <strong>health</strong> funds<br />

allocated to district <strong>health</strong> services, which <strong>in</strong>clude primary <strong>health</strong>care cl<strong>in</strong>ics and community <strong>health</strong><br />

centres, district hospitals and AIDS <strong>in</strong>terventions. In contrast, private <strong>sector</strong> spend<strong>in</strong>g has moved away<br />

from PHC towards fund<strong>in</strong>g major medical benefits such as hospitals, specialists and chronic diseases.<br />

Payroll expenses comprise 56% of prov<strong>in</strong>cial <strong>health</strong> expenditure and escalated by 19% per annum over<br />

<strong>the</strong> four years from 2005/06 to 2008/09.<br />

Both <strong>the</strong> public and private <strong>health</strong> <strong>sector</strong>s are experienc<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>creased demand <strong>for</strong> services. At <strong>the</strong> same<br />

time South Africa is also affected by <strong>the</strong> worldwide shortages of <strong>health</strong> workers. As highly mobile <strong>health</strong><br />

professionals migrate to more developed economies, valuable <strong>skills</strong> are lost and local <strong>health</strong> services are<br />

adversely impacted. Similar experiences <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> veter<strong>in</strong>ary profession cont<strong>in</strong>ue to cause <strong>skills</strong> shortages<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> public <strong>sector</strong> where <strong>the</strong> vacancy rate at national, prov<strong>in</strong>cial and laboratory levels rema<strong>in</strong>s high.<br />

The 2008 global economic crisis and economic downturn impacted <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong> <strong>sector</strong> on several levels.<br />

As tax revenues decl<strong>in</strong>e due to economic contraction, <strong>health</strong> budgets, allocations <strong>for</strong> human resources<br />

xii

and tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g are directly affected. Demand <strong>for</strong> public <strong>health</strong> services is likely to <strong>in</strong>crease due to job<br />

losses (and loss of employment-l<strong>in</strong>ked medical <strong>in</strong>surance cover). This will add fur<strong>the</strong>r pressure on <strong>health</strong><br />

professionals and workers <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> public <strong>sector</strong>.<br />

South Africa is encumbered by a quadruple burden of disease attributable to diseases of poverty, <strong>the</strong><br />

HIV and AIDS pandemic, high <strong>in</strong>cidence of communicable diseases and tuberculosis <strong>in</strong>fection, as well as<br />

high levels of chronic diseases and <strong>in</strong>ter-personal violence. This disease burden is four times larger than<br />

<strong>in</strong> developed countries and is generally double that of o<strong>the</strong>r develop<strong>in</strong>g countries. The public <strong>sector</strong><br />

bears <strong>the</strong> brunt of <strong>the</strong> problems.<br />

It is widely recognised that care levels, outcomes and management of <strong>the</strong> public <strong>health</strong> system are<br />

under stra<strong>in</strong> partly because of significant staff shortages, a mal-distribution of <strong>skills</strong> between urban and<br />

rural areas, and an <strong>in</strong>adequate <strong>skills</strong> base. Management of <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong> system is under stra<strong>in</strong> at almost<br />

all levels. Wide-spread <strong>in</strong>efficiencies result <strong>in</strong> services that are unresponsive to <strong>health</strong> and patient<br />

needs, and a lack of accountability exists on a large scale.<br />

Almost every aspect of <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong> system is regulated by <strong>the</strong> national Department of Health (DoH), while<br />

<strong>the</strong> professional councils regulate <strong>the</strong> quality of <strong>the</strong> country’s <strong>health</strong> workers. Responsibility <strong>for</strong><br />

develop<strong>in</strong>g human resources <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> public <strong>sector</strong> are split between <strong>the</strong> national and prov<strong>in</strong>cial levels.<br />

The national DoH has to promote adherence to norms and standards <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g of human<br />

resources, while <strong>the</strong> n<strong>in</strong>e prov<strong>in</strong>cial departments of <strong>health</strong> are responsible to <strong>plan</strong>, manage and develop<br />

human resources to render <strong>health</strong> services.<br />

A key priority <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> national DoH is <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>troduction of a national <strong>health</strong> <strong>in</strong>surance (NHI) system<br />

offer<strong>in</strong>g universal coverage and free <strong>health</strong> services to all South Africans by 2014; i.e. with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>plan</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g horizon of this SSP. Although <strong>the</strong> proposals are still under development and subject to change,<br />

<strong>the</strong> HWSETA should take <strong>in</strong>to account <strong>the</strong> implications <strong>for</strong> human resources needs and <strong>skills</strong><br />

requirements, especially consider<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> long lead-time required to tra<strong>in</strong> <strong>health</strong>care professionals.<br />

Although <strong>the</strong> details of <strong>the</strong> scheme are not yet known, it will extend access to private care and some<br />

analysts expect an <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> demand <strong>for</strong> services of general medical practitioners and specialists as<br />

patients will move away from public cl<strong>in</strong>ics and hospitals. In <strong>the</strong> NHI system itself, considerable<br />

managerial, f<strong>in</strong>ancial and <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation technology management <strong>skills</strong> will be required to monitor usage<br />

and benefits offered, as well as <strong>the</strong> distribution of resources and <strong>the</strong> costs of <strong>the</strong> scheme.<br />

Current national <strong>health</strong> policies focus on <strong>the</strong> provision of primary care and community-based <strong>health</strong><br />

services; expanded HIV and AIDS and TB treatment; improv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong> of mo<strong>the</strong>rs, babies and<br />

children; improv<strong>in</strong>g management and governance of <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong> system; and improv<strong>in</strong>g human resources<br />

<strong>plan</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g. On <strong>the</strong> animal <strong>health</strong> side, <strong>the</strong>re are <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g calls to make veter<strong>in</strong>ary services more<br />

accessible to low-<strong>in</strong>come communities at local government level and to <strong>in</strong>troduce mid-level veter<strong>in</strong>ary<br />

workers such as primary animal <strong>health</strong>care workers and community animal <strong>health</strong> workers to serve<br />

animal <strong>health</strong> needs <strong>in</strong> impoverished communities.<br />

xiii

Implementation of <strong>the</strong>se policies drive <strong>the</strong> need <strong>for</strong> more professional and technical <strong>health</strong>care,<br />

leadership and management <strong>skills</strong>, as well as <strong>skills</strong> development <strong>in</strong>terventions to enhance <strong>the</strong> <strong>skills</strong><br />

content.<br />

DEMAND FOR SKILLS<br />

The <strong>health</strong> <strong>sector</strong> is a personal services <strong>in</strong>dustry where services are both resource- and time-<strong>in</strong>tensive.<br />

Effective delivery of <strong>health</strong> services depends upon <strong>the</strong> availability of skilled human resources with <strong>the</strong><br />

appropriate <strong>skills</strong>. A grow<strong>in</strong>g demand <strong>for</strong> <strong>health</strong>care and <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>troduction of changes <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> way <strong>health</strong><br />

services are delivered to <strong>the</strong> public, drive <strong>the</strong> demand <strong>for</strong> <strong>skills</strong>. Such demand cont<strong>in</strong>ues to outstrip<br />

supply.<br />

In 2010 <strong>the</strong>re were approximately 281 000 filled positions <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Public Service Health Departments. At<br />

<strong>the</strong> time <strong>the</strong> total number of funded vacancies was not known, and <strong>the</strong> total number of positions<br />

available <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Public Service could not be calculated. However, <strong>the</strong> scarce <strong>skills</strong> <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation obta<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

through <strong>the</strong> Public Service Departments’ WSPs <strong>in</strong>dicate that vacancy rates are quite high and that <strong>the</strong><br />

Public Service total establishment is considerably larger than what is reflected <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> current<br />

employment figures. The number of current posts is only slightly higher than that of 1997/98 and has<br />

not <strong>in</strong>creased to allow <strong>for</strong> population growth or <strong>the</strong> impact of AIDS. Calculations by <strong>health</strong> economists<br />

us<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> 1997/98 staff<strong>in</strong>g levels as a basel<strong>in</strong>e showed that <strong>the</strong> public <strong>sector</strong> required a staff<br />

complement of 315,087 by 2008, just to keep up with population growth and <strong>the</strong> expand<strong>in</strong>g disease<br />

burden. Clearly current post levels are <strong>in</strong>adequate to meet demand <strong>for</strong> <strong>health</strong>care services <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> public<br />

<strong>sector</strong>.<br />

A conservative estimate <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> number of employees <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> private <strong>sector</strong> is 178 921 dur<strong>in</strong>g June 2010.<br />

The vacancy rate <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> private <strong>sector</strong> is estimated at 2.3%. By contrast, <strong>the</strong> public <strong>sector</strong> experiences a<br />

high vacancy rate of up to 60% <strong>in</strong> certa<strong>in</strong> professional categories.<br />

One-third of <strong>the</strong> vacancies that are difficult to fill <strong>in</strong> private <strong>health</strong> organisations are <strong>for</strong> professional<br />

positions, while 47% of <strong>the</strong> scarce <strong>skills</strong> reported <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Public Service are <strong>for</strong> professionals. Vacancies <strong>in</strong><br />

professional positions that both <strong>the</strong> public and private <strong>sector</strong>s f<strong>in</strong>d most difficult to fill exist <strong>for</strong> doctors,<br />

medical specialists, professional nurses and pharmacists. O<strong>the</strong>r scarce and critical <strong>skills</strong> needs <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

public <strong>sector</strong> are <strong>for</strong> managers <strong>in</strong> f<strong>in</strong>ance and <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation technology and <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong>care fields of<br />

dietetics and physio<strong>the</strong>rapy.<br />

Employment of doctors and nurses <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> public <strong>sector</strong> falls short of <strong>in</strong>ternational benchmarks <strong>for</strong> <strong>in</strong>hospital<br />

care and WHO m<strong>in</strong>imum guidel<strong>in</strong>es. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>the</strong> WHO, countries with fewer than 230<br />

doctors, nurses and midwives per 100 000 population generally fail to achieve adequate coverage rates<br />

of care to atta<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong>-related Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). Those goals relate to<br />

reduc<strong>in</strong>g child mortality, improv<strong>in</strong>g maternal <strong>health</strong> and combat<strong>in</strong>g HIV and AIDS and o<strong>the</strong>r diseases. In<br />

2008 <strong>the</strong> public <strong>sector</strong> had 152 doctors and professional nurses per 100 000 of <strong>the</strong> population and, if<br />

staff nurses are also <strong>in</strong>cluded, <strong>the</strong> ratio improves to 209.<br />

xiv

In public <strong>health</strong>, shortages were mostly related to growth <strong>in</strong> demand, difficulties to reta<strong>in</strong> or replace<br />

qualified staff, geographic location, new technology, and migration of employees.<br />

Skills development targets <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong> <strong>sector</strong> set by <strong>the</strong> DoH <strong>in</strong> 2006 <strong>in</strong>dicate <strong>the</strong> scope of demand <strong>for</strong><br />

<strong>skills</strong>, but failed to acknowledge supply-side constra<strong>in</strong>ts to a sufficient degree. Some of <strong>the</strong>se<br />

constra<strong>in</strong>ts are considered <strong>in</strong> Chapter 5 of this SSP.<br />

Programmes to accelerate HIV test<strong>in</strong>g and <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>the</strong> number of patients on anti-retroviral treatment<br />

(ART) by almost three times will have a major impact on <strong>the</strong> demand <strong>for</strong> <strong>skills</strong>. More specifically, <strong>the</strong><br />

public <strong>sector</strong> will need additional doctors, medical specialists, nurses, adm<strong>in</strong>istrative support staff (to<br />

order, collect and distribute drugs) and skilled <strong>health</strong> managers to implement and oversee operations.<br />

Demand <strong>for</strong> similar <strong>skills</strong> is triggered when key programmes to fight TB and improve <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong> of<br />

mo<strong>the</strong>rs, children and women are rolled out. More lower-level <strong>skills</strong> and community <strong>health</strong> workers are<br />

needed to monitor adherence to treatment regimes <strong>for</strong> AIDS and TB. Skills <strong>in</strong>terventions should also<br />

target PHC nurses <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> <strong>health</strong> monitor<strong>in</strong>g programmes <strong>for</strong> children.<br />

Specialised tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g on a large scale is required <strong>in</strong> TB management and <strong>in</strong>fection control, and staff nurses<br />

require targeted tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> midwifery, antenatal, obstetric and post-natal care.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> public <strong>sector</strong>, and <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> district <strong>health</strong> system <strong>in</strong> particular, leadership <strong>skills</strong> and professional<br />

management <strong>skills</strong> are required to manage complex systems and to improve operational efficiency.<br />

Skills <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>plan</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g and implementation of programmes, as well as <strong>the</strong> monitor<strong>in</strong>g and evaluation of<br />

service and quality of care, are required. On <strong>the</strong> people side, <strong>skills</strong> are needed to manage human<br />

resources and <strong>the</strong>ir per<strong>for</strong>mance. More particularly, managers require <strong>skills</strong> to lead and guide<br />

subord<strong>in</strong>ates, improve <strong>the</strong>ir productivity and <strong>in</strong>still accountability <strong>for</strong> service to patients. O<strong>the</strong>r areas<br />

<strong>for</strong> managerial development <strong>in</strong>clude <strong>plan</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g and time utilisation, use of <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation technology, as<br />

well as f<strong>in</strong>ancial and capital resources management. Extensive, <strong>in</strong>tensive and purposive <strong>skills</strong><br />

development is needed <strong>in</strong> all <strong>the</strong>se areas.<br />

F<strong>in</strong>ally, <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>troduction of a national <strong>health</strong> <strong>in</strong>surance system will drive demand <strong>for</strong> higher levels of care<br />

offered by doctors and medical specialists and is expected to turn utilisation of <strong>health</strong> services away<br />

from nurse-based primary care.<br />

SUPPLY OF SKILLS<br />

This section describes <strong>the</strong> different elements of supply and highlights <strong>the</strong> supply-side constra<strong>in</strong>ts that<br />

contribute to <strong>the</strong> current shortages. The supply of <strong>skills</strong> can be correlated directly with outputs from <strong>the</strong><br />

school system, graduation trends, professional registration and <strong>the</strong> role that <strong>the</strong> HWSETA plays <strong>in</strong> <strong>skills</strong><br />

development.<br />

A comb<strong>in</strong>ation of complex factors <strong>in</strong>fluences <strong>the</strong> supply of <strong>skills</strong> to <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong> <strong>sector</strong>. At <strong>the</strong> heart of <strong>the</strong><br />

problem is <strong>the</strong> quantity and quality of learners who complete high school. The secondary school system<br />

is produc<strong>in</strong>g fewer candidates with <strong>the</strong> comb<strong>in</strong>ation of ma<strong>the</strong>matics, physical sciences and/or life<br />

sciences required to enter tertiary level studies <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong> sciences. The latest available matriculation<br />

xv

statistics are <strong>for</strong> 2008 when <strong>the</strong> New Curriculum Statement was <strong>in</strong>troduced. A total of 554 664<br />

candidates wrote <strong>the</strong> Grade 12 exam<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>in</strong> 2008. Of those, a total of300 008 wrote ma<strong>the</strong>matics<br />

and 89 186 (16%) achieved 40% and above <strong>in</strong> ma<strong>the</strong>matics, while 61 480 candidates passed physical<br />

sciences (or 11% of candidates who wrote Grade 12). A total of 29 8210 candidates wrote <strong>the</strong> life<br />

sciences exam<strong>in</strong>ation and 117 483 achieved 40% and above.<br />

Quality standards of education <strong>in</strong> ma<strong>the</strong>matics, physical sciences and life sciences are major supply-side<br />

constra<strong>in</strong>ts impact<strong>in</strong>g on <strong>the</strong> <strong>skills</strong> of <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong> <strong>sector</strong>. Sub-standard levels of literacy and numeracy<br />

<strong>skills</strong> of school leavers and <strong>the</strong>ir poor level of read<strong>in</strong>ess <strong>for</strong> tertiary studies fur<strong>the</strong>r reduce <strong>the</strong> supply<br />

pool.<br />

Exist<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>stitutional arrangements and regulatory provisions regard<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g of <strong>health</strong><br />

professionals also restrict <strong>the</strong> supply of <strong>skills</strong> to <strong>the</strong> <strong>sector</strong>. Most of <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong> professionals who are<br />

required to register with <strong>the</strong> HPCSA, <strong>the</strong> SANC, <strong>the</strong> SACP and <strong>the</strong> SAVC are tra<strong>in</strong>ed by universities and<br />

universities of technology, and undergo practical tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> state-owned academic <strong>health</strong> complexes.<br />

Production levels at <strong>the</strong>se <strong>in</strong>stitutions are limited due to capacity and budget constra<strong>in</strong>ts. Regulatory<br />

requirements prevent private <strong>sector</strong> tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g providers from tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g many categories of <strong>health</strong><br />

professionals.<br />

With <strong>the</strong> exception of basic <strong>health</strong>care sciences, <strong>the</strong> growth <strong>in</strong> supply of new graduates from <strong>the</strong> higher<br />

education system has been moderate, and even low over <strong>the</strong> last decade. If all <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong>-related fields<br />

of study are considered, <strong>the</strong> total output from <strong>the</strong> Higher Education and Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g (HET)<strong>sector</strong> grew on<br />

average by 3.4% at National Diploma level, at 6.3% at <strong>the</strong> first three-year BDegree level and at 5.1% at<br />

<strong>the</strong> first four-year degree level. The field with <strong>the</strong> highest growth was Basic Health Care Sciences.<br />

Cl<strong>in</strong>ical Health Sciences (which more or less represents <strong>the</strong> output of entry-level medical degrees) grew<br />

only moderately – by 3.1% per year.<br />

This trend is carried through to <strong>the</strong> registration of <strong>health</strong> professionals with <strong>the</strong>ir respective professional<br />

councils. The average annual growth rate <strong>in</strong> professional registrations across key occupational<br />

categories has been low, and <strong>in</strong> some <strong>in</strong>stances lower than <strong>the</strong> growth rates <strong>in</strong> graduates produced <strong>for</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> particular professional category.<br />

Nurs<strong>in</strong>g colleges play an important role <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g of nurses. Total output from nurs<strong>in</strong>g colleges<br />

grew on average by 10% per year over <strong>the</strong> period 2000 to 2009. The largest growth was at <strong>the</strong> level of<br />

pupil nurses and pupil auxiliaries.<br />

The HWSETA also contributes to <strong>skills</strong> <strong>for</strong>mation <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong> <strong>sector</strong>. S<strong>in</strong>ce 2002 more than 25 000<br />

learners enrolled on <strong>health</strong>-related learnerships. More than 7 000 have completed learnerships at <strong>the</strong><br />

time of writ<strong>in</strong>g this SSP, and were recorded on <strong>the</strong> HWSETA’s electronic system. Many more completed<br />

learnership that are quality assured by professional councils and <strong>the</strong>ir achievements are recorded by <strong>the</strong><br />

councils and not by <strong>the</strong> HWSETA. The SETA also support <strong>skills</strong> development through <strong>in</strong>ternships and<br />

workplace tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g programmes, <strong>skills</strong> programmes, ABET and small enterprise development.<br />

xvi

The supply of <strong>skills</strong> to <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong> <strong>sector</strong> is not only determ<strong>in</strong>ed by capacity at tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>stitutions and<br />

<strong>the</strong> scope of tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g activities. Health workers risk exposure to HIV and AIDS <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> workplace and face<br />

<strong>in</strong>creased risks of contract<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> disease compared with workers <strong>in</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>sector</strong>s. By 2002 <strong>the</strong><br />

prevalence rate of HIV and AIDS among <strong>health</strong> workers was 15.7%, much higher than <strong>the</strong> national<br />

prevalence rate at <strong>the</strong> height of <strong>the</strong> pandemic <strong>in</strong> 2010. As a result of AIDS, skilled <strong>health</strong> workers leave<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>sector</strong> prematurely, ei<strong>the</strong>r because <strong>the</strong>y fear <strong>in</strong>fection, become ill <strong>the</strong>mselves or need to care <strong>for</strong><br />

o<strong>the</strong>rs who fall ill.<br />

The supply-side analysis presented <strong>in</strong> Chapter 5 of this SSP shows that many of <strong>the</strong> government’s<br />

positive strategies to improve <strong>the</strong> supply and retention of <strong>skills</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>sector</strong> may be compromised by<br />

budget constra<strong>in</strong>ts and various <strong>in</strong>stitutional problems such as weak management systems, subfunctional<br />

work<strong>in</strong>g environments and poor human resources practices. The analysis also lead to <strong>the</strong><br />

conclusion that unless major improvements <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> leadership and management of <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong> system at<br />

all levels are made, migration of <strong>health</strong> professionals out of <strong>the</strong> public <strong>sector</strong> and emigration to o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

countries are likely to dra<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> supply of <strong>skills</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> considerable future.<br />

SKILLS DEVELOPMENT PRIORITIES OF THE HWSETA<br />

Given <strong>the</strong> nature and magnitude of <strong>the</strong> <strong>skills</strong> development challenges <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong> <strong>sector</strong>, a concerted<br />

and <strong>in</strong>tegrated ef<strong>for</strong>t is required <strong>in</strong> partnership with <strong>the</strong> national DoH, DHET, <strong>the</strong> higher education<br />

<strong>sector</strong>, private education and tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g providers, public and private <strong>health</strong> facilities and <strong>the</strong> HWSETA. As<br />

one of several <strong>in</strong>stitutions tasked with fund<strong>in</strong>g and facilitat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>skills</strong> development <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong> <strong>sector</strong>,<br />

<strong>the</strong> HWSETA will focus its attention <strong>in</strong> a number of priority areas <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> five-year period covered by NSDS<br />

III.<br />

The HWSETA’s contribution to Government’s objectives will centre around close cooperation with <strong>the</strong><br />

DoH, support <strong>for</strong> <strong>health</strong> strategies through <strong>skills</strong> development and, with<strong>in</strong> mandate and budget<br />

parameters, enabl<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> supply of larger numbers of <strong>health</strong> workers equipped with <strong>the</strong> <strong>skills</strong> necessary<br />

to improve <strong>health</strong>care <strong>in</strong> South Africa. It must, however, be noted that <strong>the</strong>se <strong>in</strong>itiatives may be<br />

hampered by a disjuncture between <strong>the</strong> different m<strong>in</strong>istries <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>plan</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>health</strong> services.<br />

Current shortages of <strong>skills</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> public <strong>health</strong> <strong>sector</strong> lead to massive <strong>in</strong>equalities <strong>in</strong> terms of access to<br />

proper <strong>health</strong>care and <strong>the</strong> perpetuation, and even <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>tensification, of <strong>in</strong>equalities <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> South<br />

African society. There<strong>for</strong>e, <strong>the</strong> HWSETA’s activities will aim to alleviate <strong>skills</strong> shortages and develop new<br />

<strong>skills</strong> that can serve <strong>the</strong> poorest segments of <strong>the</strong> population and under-resourced areas. Skills<br />

development support will give preference to historically disadvantaged <strong>in</strong>dividuals.<br />

The HWSETA will, <strong>in</strong> collaboration with universities and FET colleges that offer <strong>health</strong> tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, support<br />

<strong>health</strong>-specific occupational programmes to facilitate access, success and progression. It <strong>in</strong>tends to<br />

develop or fund general bridg<strong>in</strong>g courses and specific bridg<strong>in</strong>g courses <strong>in</strong> ma<strong>the</strong>matics and science, and<br />

to work on a support strategy that will be aimed at <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> pass rate of undergraduate students.<br />

A structured career guidance strategy will be developed to reach out to school learners and create<br />

awareness of <strong>the</strong> occupations <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong> <strong>sector</strong> at all levels.<br />

xvii

In collaboration with <strong>the</strong> professional bodies <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong> <strong>sector</strong>, <strong>the</strong> HWSETA will cont<strong>in</strong>ue with its<br />

work towards <strong>the</strong> recognition of prior learn<strong>in</strong>g (RPL). The key focus will be on <strong>the</strong> development and<br />

implementation of an RPL support strategy and <strong>the</strong> development of national assessment centres.<br />

Support <strong>for</strong> vocational adult basic education (ABET) will also cont<strong>in</strong>ue to enable people who were<br />

previously excluded from <strong>for</strong>mal education to improve <strong>the</strong>ir qualifications.<br />

The HWSETA will also support pivotal occupational programmes; i.e. professional, vocational, technical<br />

and academic learn<strong>in</strong>g programmes that meet <strong>the</strong> critical needs <strong>for</strong> economic growth and social<br />

development. Research will be undertaken to identify <strong>the</strong> occupations that need to be supported<br />

through <strong>the</strong> proposed Pivotal Grant. The HWSETA will also accredit workplaces <strong>for</strong> deliver<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong><br />

workplace components of pivotal programmes and address <strong>the</strong> <strong>skills</strong> needs of staff <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> deliver<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>the</strong> workplace component of pivotal learn<strong>in</strong>g programmes. Fur<strong>the</strong>r, <strong>the</strong> HWSETA will publicise <strong>the</strong><br />

scarce <strong>skills</strong> identified <strong>in</strong> this SSP and <strong>the</strong> learnerships that provide entry to <strong>the</strong>se occupations. It will<br />

also make discretionary fund<strong>in</strong>g available <strong>for</strong> learnership support.<br />

The HWSETA will develop a postgraduate <strong>in</strong>ternship support strategy, <strong>in</strong> conjunction with employers, to<br />

provide unemployed graduates with workplace placements and exposure.<br />

Discretionary fund<strong>in</strong>g will be made available to support <strong>skills</strong> programmes and non-accredited short<br />

courses. The HWSETA will cooperate with <strong>the</strong> professional councils to develop a CPD support strategy.<br />

A strategy will be prepared to support <strong>the</strong> development of academic capacity and <strong>in</strong>novation via a<br />

postgraduate bursary scheme.<br />

The HWSETA will also support measures to streng<strong>the</strong>n its own capacity as well as that of its delivery<br />

partners.<br />

These <strong>skills</strong> development priorities and <strong>in</strong>terventions will be implemented with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> available fund<strong>in</strong>g<br />

of <strong>the</strong> SETA. The success and impact of <strong>the</strong>se strategies will be assessed on an ongo<strong>in</strong>g basis and <strong>the</strong><br />