2 The story of Granite and Bega Cheese - Sapphire Coast

2 The story of Granite and Bega Cheese - Sapphire Coast

2 The story of Granite and Bega Cheese - Sapphire Coast

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

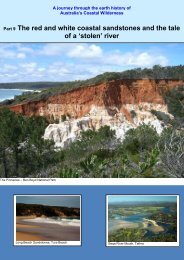

A journey through the earth hi<strong>story</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

Australia’s <strong>Coast</strong>al Wilderness<br />

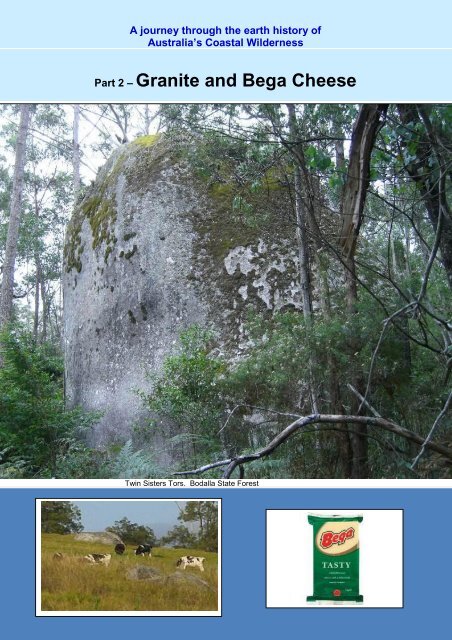

Part 2 – <strong>Granite</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Bega</strong> <strong>Cheese</strong><br />

Twin Sisters Tors, Bodalla State Forest<br />

2. <strong>The</strong> <strong>story</strong> <strong>of</strong> granite <strong>and</strong> <strong>Bega</strong> <strong>Cheese</strong>

Our journey starts at Moruya about 300 km south <strong>of</strong> Sydney, on the northern extent<br />

<strong>of</strong> Australia’s <strong>Coast</strong>al Wilderness. <strong>The</strong> <strong>story</strong> begins with the Moruya <strong>Granite</strong> that has<br />

historic ties with Sydney Harbour Bridge, built between 1924 <strong>and</strong> 1932. <strong>The</strong> massive<br />

supporting bridge pylons are built from dressed granite rock obtained from a quarry<br />

at Moruya.<br />

North Pylon – Sydney Harbour Bridge<br />

Moruya is a pleasant town next to a tidal river on a coastal flood plain set in a fertile<br />

grassy l<strong>and</strong>scape against the mountainous backdrop <strong>of</strong> the rugged eastern<br />

escarpment.<br />

<strong>The</strong> historic Moruya <strong>Granite</strong> quarry is on the north side <strong>of</strong> the Moruya River 3 km<br />

downstream from the Moruya Bridge. <strong>The</strong> grey granite, specked with black mica, is<br />

massive, with very few fractures. Not a single block was rejected by the masons on<br />

the bridge construction site.<br />

Historic Moruya Quarry<br />

Adjacent wharf

<strong>The</strong> dairy farm grassl<strong>and</strong>s, cleared <strong>of</strong> eucalypt forests, are typical <strong>of</strong> the rich soils<br />

formed on granite rocks. <strong>The</strong> grassl<strong>and</strong>s here are the northern margins <strong>of</strong> the<br />

granites <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Bega</strong> Batholith. This huge suite <strong>of</strong> granite is composed <strong>of</strong> over 130<br />

separate plutons (including the Moruya <strong>Granite</strong>) covering some 9000 square km <strong>of</strong><br />

south eastern Australia. <strong>Granite</strong>s <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Bega</strong> Batholith, extend from Moruya in the<br />

north east to the south at Cape Conran, <strong>and</strong> Mallacoota in the Victorian part <strong>of</strong><br />

Australia’s <strong>Coast</strong>al Wilderness. A tiny granite outcrop in Canberra may be the north<br />

westerly extent <strong>of</strong> this batholith.<br />

A batholith (from Greek bathos, depth + lithos, rock) is a large emplacement <strong>of</strong><br />

igneous intrusive (also called plutonic) rock that forms from cooled magma deep in<br />

the earth's crust. Batholiths are usually made up <strong>of</strong> granite or chemically similar<br />

rock.<br />

A pluton in geology is a single body <strong>of</strong> intrusive igneous rock that crystallized from<br />

magma slowly cooling below the surface <strong>of</strong> the Earth. (Wikepedia).<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Bega</strong> Batholith granites crystallised from melted rock deep in the earth’s crust<br />

some 420 to 400 million years ago (Mya), being the early-mid Devonian period.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se granites formed in response to the interaction <strong>of</strong> tectonic plates at the eastern<br />

margin <strong>of</strong> the old supercontinent <strong>of</strong> Gondwana, shown in the figure. Crustal melting

took place l<strong>and</strong>wards <strong>of</strong> the plate boundary, the so-called Palaeo-Pacific oceanic<br />

trench, with the oceanic plate sliding under (subducting beneath) the thick<br />

Gondwanan continental crust. As the oceanic plate sank, under increasing<br />

temperature <strong>and</strong> pressure <strong>and</strong> reactions with water saturated sediment, the rock<br />

materials melted <strong>and</strong> then rose like huge hot air balloons up through the crust (the<br />

plutons).<br />

If such molten rock, or magma, reaches the surface it can form explosive <strong>and</strong>esite<br />

volcanoes that are common today around the Pacific Ocean ‘ring <strong>of</strong> fire’ (actually a<br />

series <strong>of</strong> tectonic plate boundaries). If the magma cools below the surface, it forms<br />

granite – a generic term that covers a wide range <strong>of</strong> silica rich igneous rocks.<br />

Variations in chemical composition give granites their diverse colours <strong>and</strong> textures<br />

that distinguish one pluton from another. <strong>The</strong>se variations make a diversity <strong>of</strong><br />

building stones. Examples <strong>of</strong> this diversity are:<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Bega</strong> granites are similar in appearance to number 3, with dominance <strong>of</strong> the<br />

white form <strong>of</strong> feldspar rather than the pink form.<br />

Igneous rock (from the Latin igneus meaning <strong>of</strong> fire) is one <strong>of</strong> the three main rock<br />

types, the others being sedimentary <strong>and</strong> metamorphic. Igneous rock is formed<br />

through the cooling <strong>and</strong> solidification <strong>of</strong> magma or lava. Igneous rock may form<br />

either below the surface as intrusive (plutonic) rocks or on the surface as extrusive<br />

(volcanic) rocks. (Wikipedia)<br />

Driving south from Moruya, you can see fine exposures <strong>of</strong> the granite in the road<br />

cuttings along the highway.<br />

<strong>Granite</strong> breaks down easily to produce the rich soil beloved by farmers, <strong>and</strong> a<br />

l<strong>and</strong>scape <strong>of</strong> gently rounded hills. Right through the region almost all <strong>of</strong> the dairy<br />

farms producing the famous <strong>Bega</strong> <strong>Cheese</strong> are on granite based soils, identified by<br />

the granite boulders dotted across the paddocks. <strong>The</strong>se boulders are easily seen

ecause the native forests were cleared by early European settlers for farming <strong>and</strong><br />

grazing. Almost all <strong>of</strong> the cleared l<strong>and</strong> between the coast <strong>and</strong> the escarpment was<br />

formerly forests growing on granite based soils.<br />

Google Earth<br />

<strong>The</strong> cleared l<strong>and</strong> in this Google Earth image shows the area <strong>of</strong> the granite based<br />

soils used for dairy farming.<br />

<strong>The</strong> granite breaks down as water penetrates joints <strong>and</strong> fractures <strong>and</strong> rots the<br />

feldspars <strong>and</strong> smooths out sharp edges to produce the characteristic clusters <strong>of</strong><br />

rounded boulders, known as tors.<br />

Dairy farm on granite l<strong>and</strong>scape, Coolagolite<br />

In the high country <strong>of</strong> the escarpment, granite tors are scattered through trees <strong>and</strong><br />

grassl<strong>and</strong> along the Snowy Mountains Highway between the top <strong>of</strong> Brown Mountain<br />

<strong>and</strong> the Maclaughlin River east <strong>of</strong> Nimmitabel. Further south in South East Forest<br />

National Park, a particularly beautiful site to enjoy forested granite l<strong>and</strong>forms is about<br />

25 km east <strong>of</strong> Bombala at Myanba Creek, with its falls <strong>and</strong> lookouts.

Myamba Lookout South East Forest National Park<br />

<strong>Granite</strong> tors, Myamba Creek<br />

Myamba Creek<br />

Spectacular views <strong>of</strong> granite escarpment can be found at Tuross Falls north east <strong>of</strong><br />

Nimmitabel in Wadbilliga National Park. <strong>The</strong> route to this site also takes the visitor<br />

through outliers on the Monaro Volcanic Province (described elsewhere on the<br />

journey) on the escarpment.<br />

Upper Tuross River Wadbilliga National Park<br />

Tuross Falls

A stop <strong>of</strong>f near Tilba Cemetery<br />

A side trip well worth the effort. Heading south, turn left at the turn<strong>of</strong>f to Central Tilba<br />

from the Princes Highway, instead <strong>of</strong> turning right to the village. Follow the sign to<br />

the cemetery towards the coast. <strong>The</strong> forestry map shows the beach as Wallaga<br />

Beach. <strong>The</strong>re is a car park <strong>and</strong> access to the beach just below the second grave<br />

enclosure. <strong>The</strong> geoheritage treasure is the headl<strong>and</strong> south <strong>of</strong> the cemetery. <strong>The</strong> site<br />

is best visited at low tide.<br />

Approaching the headl<strong>and</strong>, the distinctive features <strong>of</strong> almost-vertical beds <strong>of</strong><br />

brownish Ordovician sedimentary rocks st<strong>and</strong> out. We will meet these very old rocks<br />

at other places along the coast. Here, we’ll look at the igneous dykes <strong>and</strong> quartz<br />

veins intruding the Ordovician beds. <strong>The</strong> first clue is the white slash in the centre <strong>of</strong><br />

the photo below.<br />

<strong>The</strong> white dykes are chemically similar to the nearby Dromedary intrusion, <strong>and</strong> were<br />

intruded at the same time as the Dromedary mass [Mount Dromedary, now called<br />

Gulgaga]<br />

An intrusive dyke is a slab-like igneous body whose thickness is smaller than the<br />

other two dimensions. Thickness can vary from sub-centimetre scale to many<br />

metres, <strong>and</strong> the lateral dimensions can extend over many kilometres. When<br />

intruded, a dyke shoulders aside pre-existing layers or bodies <strong>of</strong> rock; this means<br />

that a dyke is always younger than the rocks that it cuts through.

So far so good but the going now gets weird. On the same headl<strong>and</strong> there is another<br />

network <strong>of</strong> dykes <strong>of</strong> granite composition, quite unlike the chemistry <strong>of</strong> Dromedary,<br />

<strong>and</strong> a granite outcrop in the s<strong>and</strong>.<br />

<strong>Granite</strong> dyke<br />

<strong>Granite</strong> outcrop<br />

We can see the granite intruding into, breaking up <strong>and</strong> assimilating the Ordovician<br />

beds.<br />

<strong>Granite</strong> intruding into the turbidite<br />

<strong>The</strong> white rock cutting across the centre <strong>of</strong> the turbidite is not another dyke but a vein<br />

composed <strong>of</strong> quartz, common in these highly deformed old rocks. <strong>The</strong> beds cut by<br />

the vein are Ordovician sedimentary rocks called turbidites.<br />

Turbidites were deposited on the deep ocean floor from very fluid s<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> mudladen<br />

avalanches cascading down continental slopes. S<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> mud gradually<br />

settled out <strong>of</strong> suspension. Successive avalanches are <strong>of</strong>ten separated in time, but<br />

can build up thick piles <strong>of</strong> sediment. <strong>The</strong> same processes occur today down the<br />

continental slope <strong>of</strong>f eastern Australia.

Geological study <strong>of</strong> this complex geological site has identified the granites as part <strong>of</strong><br />

the <strong>Bega</strong> Batholith. <strong>The</strong> nearest granite outcrop, the Cobargo Pluton, is 14km away.<br />

<strong>The</strong> two sets <strong>of</strong> dykes on this headl<strong>and</strong> are separated by some 323 million years.<br />

Instead <strong>of</strong> returning to the cemetery, walk to the other headl<strong>and</strong> at the northern end<br />

<strong>of</strong> the beach. This headl<strong>and</strong> is entirely made up <strong>of</strong> the Cretaceous lavas <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Dromedary province encountered at 1080 Beach (the next headl<strong>and</strong> north).<br />

In the front boulder the mixing <strong>of</strong> chunks in the lava soup can be easily seen.<br />

<strong>Granite</strong> shaping the l<strong>and</strong>scapes<br />

<strong>The</strong> term ‘granite’ embraces a wide range <strong>of</strong> rocks differing in their composition,<br />

chemistry, depth <strong>and</strong> temperature at the time <strong>of</strong> formation. <strong>The</strong> <strong>Bega</strong> Batholith is<br />

made up <strong>of</strong> over 130 plutons. Many <strong>of</strong> them are quite different in their crystalline<br />

texture <strong>and</strong> composition <strong>and</strong> this has helped to map the extent <strong>of</strong> each pluton.<br />

Some granites are more susceptible to weathering than others, so that they break<br />

down more easily into s<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> soil. Contrasts in weathering <strong>and</strong> susceptibility to<br />

erosion in different rock types, including granites, is a major factor in determining the<br />

shape <strong>and</strong> structure <strong>of</strong> the l<strong>and</strong>scape we see today. One example is in the Cobargo<br />

area shown below.<br />

Google Earth

<strong>The</strong> grassl<strong>and</strong> on the Cobargo <strong>Granite</strong> st<strong>and</strong>s out as it has been cleared <strong>of</strong> native<br />

forest to expose fertile soils well suited to pasture <strong>and</strong> dairy farming. <strong>The</strong> area<br />

producing prime cheese coincides with the geology map.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Ordovician sedimentary rocks form elevated, erosion-resistant ridges where they<br />

abut the granite. Hot, molten granites intruded into the Ordovician rocks deep in the<br />

crust, cooking them in the process, resulting in a b<strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong> hard heat-altered rock<br />

against the granite. Erosion <strong>and</strong> weathering over millions <strong>of</strong> years has left the<br />

contact zone st<strong>and</strong>ing out as rugged ridges, while the granite has washed away or<br />

formed deep soils.<br />

Just to the south <strong>of</strong> the Cobargo <strong>Granite</strong>s is Mumbulla Mountain, composed <strong>of</strong> a<br />

quite different granite type. This is far more resistant to erosion <strong>and</strong> st<strong>and</strong>s out as a<br />

rugged range above the adjacent Cobargo granite l<strong>and</strong>scape cleared for agriculture.<br />

Mumbulla Mountain from Princes Highway<br />

Google Earth<br />

Similar examples <strong>of</strong> the l<strong>and</strong>scape that reflect different erosion rates occur across the<br />

region. <strong>The</strong> view from Piper’s Lookout on the Snowy Mountains Highway at the top <strong>of</strong><br />

the steep climb from Bemboka on Brown Mountain shows rolling grassl<strong>and</strong> stretching<br />

almost to the coast 50 km away. As at Cobargo, the grassl<strong>and</strong> represents areas <strong>of</strong><br />

fertile soil weathered from <strong>Bega</strong> Batholith granites, now cleared for pasture.<br />

Forested hills to the left mark the cooked rocks intruded by the granite.<br />

View from Pipers (Brown Mountain) Lookout<br />

<strong>The</strong> weathered granite is well exposed in road cuttings seen during the ascent to<br />

Piper’s Lookout. <strong>The</strong> yellow material is a mixture <strong>of</strong> s<strong>of</strong>t clay <strong>and</strong> s<strong>and</strong> formed from<br />

breakdown <strong>of</strong> minerals in the granite. Occasional large rounded boulders embedded<br />

in this material are all that is left from the once massive rock. When wet, the clay <strong>and</strong>

s<strong>and</strong> has no strength <strong>and</strong> readily slumps downhill, making this a road builder’s<br />

nightmare.<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Bega</strong> <strong>Granite</strong> <strong>story</strong> does not end here, it continues well inl<strong>and</strong> from Piper’s<br />

Lookout. Boulder outcrops (tors) appear among the forest <strong>and</strong> in grassy areas along<br />

the Snowy Mountains Highway. Formation <strong>of</strong> the steeply sloping escarpment, its<br />

face cut by deep gorges, is another fascinating <strong>story</strong>. This is described in Part 3 <strong>of</strong><br />

our journey.