English - MTU Onsite Energy

English - MTU Onsite Energy

English - MTU Onsite Energy

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>MTU</strong> Brown <strong>MTU</strong> Brown<br />

0-17-28-62 80% der Farbe 60%<br />

CMYK CMYK CMYK<br />

<strong>MTU</strong> Blue <strong>MTU</strong> Blue<br />

60%<br />

50-25-0-10 80% der Farbe<br />

CMYK<br />

CMYK CMYK<br />

40%<br />

CMYK<br />

40%<br />

CMYK<br />

20%<br />

CMYK<br />

20%<br />

CMYK<br />

Mining<br />

For thousands of years man has looked to<br />

extract the planet’s minerals in one form or<br />

another. South Africa has always been at the<br />

forefront of this endeavour, starting with<br />

ancient civilisations looking to access the<br />

mystical powers of gold, to the famed gold<br />

rush in the 1880s. In fact, it would be safe<br />

to say that South Africa has led the world in<br />

the last 150 years with the city of Johannesburg<br />

or Egoli (Xhosa for City of Gold) –<br />

Africa’s economic powerhouse – having risen<br />

out of the original gold mines. All across the<br />

northern reaches of the country there are<br />

areas where mining is not only a way of life,<br />

but a life line.<br />

In one of the poorest provinces of South Africa,<br />

with 22% unemployment and other major socioeconomic<br />

issues, a job is what holds the key for<br />

most. With mining being the dominant industry<br />

and provider of jobs in the officially liquidated<br />

Limpopo Province, it is no wonder that families<br />

like Pompie Makgoba’s have been in the mining<br />

business for generations. It also makes it easier<br />

to understand why he and thousands of others<br />

wake up at 3:30 am every day to start work on<br />

the mines at 6 am. Pompie drives two hours just<br />

to get to work each day and roughly the same to<br />

get home to his wife and three children.<br />

Modikwa Platinum Mine<br />

Modikwa Platinum Mine has been in operation<br />

since 2003 and lies in a lush, subtropical igneous<br />

complex that spans hundreds of kilometres.<br />

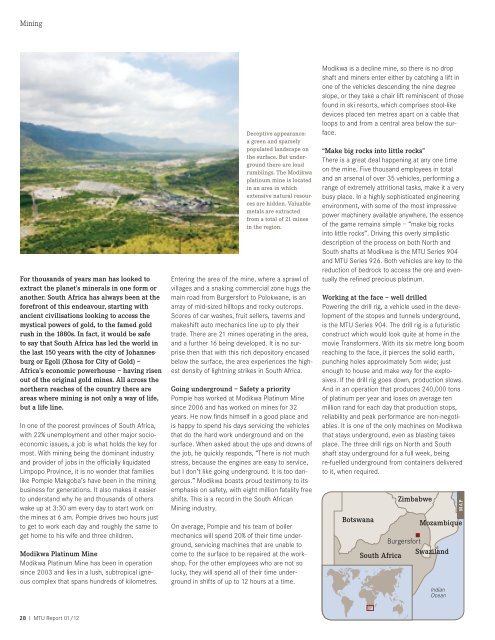

Deceptive appearance:<br />

a green and sparsely<br />

populated landscape on<br />

the surface. But underground<br />

there are loud<br />

rumblings. The Modikwa<br />

platinum mine is located<br />

in an area in which<br />

extensive natural resources<br />

are hidden. Valuable<br />

metals are extracted<br />

from a total of 21 mines<br />

in the region.<br />

Entering the area of the mine, where a sprawl of<br />

villages and a snaking commercial zone hugs the<br />

main road from Burgersfort to Polokwane, is an<br />

array of mid-sized hilltops and rocky outcrops.<br />

Scores of car washes, fruit sellers, taverns and<br />

makeshift auto mechanics line up to ply their<br />

trade. There are 21 mines operating in the area,<br />

and a further 16 being developed. It is no surprise<br />

then that with this rich depository encased<br />

below the surface, the area experiences the highest<br />

density of lightning strikes in South Africa.<br />

Going underground – Safety a priority<br />

Pompie has worked at Modikwa Platinum Mine<br />

since 2006 and has worked on mines for 32<br />

years. He now finds himself in a good place and<br />

is happy to spend his days servicing the vehicles<br />

that do the hard work underground and on the<br />

surface. When asked about the ups and downs of<br />

the job, he quickly responds, “There is not much<br />

stress, because the engines are easy to service,<br />

but I don’t like going underground. It is too dangerous.”<br />

Modikwa boasts proud testimony to its<br />

emphasis on safety, with eight million fatality free<br />

shifts. This is a record in the South African<br />

Mining industry.<br />

On average, Pompie and his team of boiler<br />

mechanics will spend 20% of their time underground,<br />

servicing machines that are unable to<br />

come to the surface to be repaired at the workshop.<br />

For the other employees who are not so<br />

lucky, they will spend all of their time underground<br />

in shifts of up to 12 hours at a time.<br />

Modikwa is a decline mine, so there is no drop<br />

shaft and miners enter either by catching a lift in<br />

one of the vehicles descending the nine degree<br />

slope, or they take a chair lift reminiscent of those<br />

found in ski resorts, which comprises stool-like<br />

devices placed ten metres apart on a cable that<br />

loops to and from a central area below the surface.<br />

“Make big rocks into little rocks”<br />

There is a great deal happening at any one time<br />

on the mine. Five thousand employees in total<br />

and an arsenal of over 35 vehicles, performing a<br />

range of extremely attritional tasks, make it a very<br />

busy place. In a highly sophisticated engineering<br />

environment, with some of the most impressive<br />

power machinery available anywhere, the essence<br />

of the game remains simple – “make big rocks<br />

into little rocks”. Driving this overly simplistic<br />

description of the process on both North and<br />

South shafts at Modikwa is the <strong>MTU</strong> Series 904<br />

and <strong>MTU</strong> Series 926. Both vehicles are key to the<br />

reduction of bedrock to access the ore and eventually<br />

the refined precious platinum.<br />

Working at the face – well drilled<br />

Powering the drill rig, a vehicle used in the development<br />

of the stopes and tunnels underground,<br />

is the <strong>MTU</strong> Series 904. The drill rig is a futuristic<br />

construct which would look quite at home in the<br />

movie Transformers. With its six metre long boom<br />

reaching to the face, it pierces the solid earth,<br />

punching holes approximately 5cm wide; just<br />

enough to house and make way for the explosives.<br />

If the drill rig goes down, production slows.<br />

And in an operation that produces 240,000 tons<br />

of platinum per year and loses on average ten<br />

million rand for each day that production stops,<br />

reliability and peak performance are non-negotiables.<br />

It is one of the only machines on Modikwa<br />

that stays underground, even as blasting takes<br />

place. The three drill rigs on North and South<br />

shaft stay underground for a full week, being<br />

re-fuelled underground from containers delivered<br />

to it, when required.<br />

Botswana<br />

South Africa<br />

Zimbabwe<br />

MAP<br />

Mozambique<br />

Burgersfort<br />

Swaziland<br />

Indian<br />

Ocean<br />

28 I <strong>MTU</strong> Report 01/12

![Full power range of diesel generator sets [PDF] - MTU Onsite Energy](https://img.yumpu.com/28297693/1/190x253/full-power-range-of-diesel-generator-sets-pdf-mtu-onsite-energy.jpg?quality=85)