UNCORRECTED PROOF - inicc

UNCORRECTED PROOF - inicc

UNCORRECTED PROOF - inicc

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

ARTICLE IN PRESS<br />

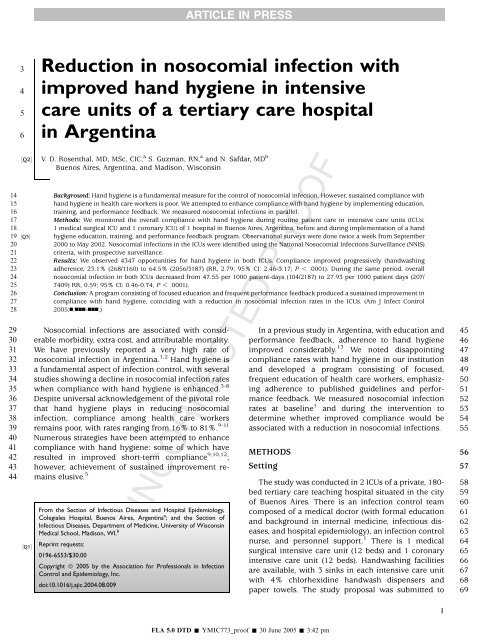

3 Reduction in nosocomial infection with<br />

4 improved hand hygiene in intensive<br />

5 care units of a tertiary care hospital<br />

6 in Argentina<br />

½Q2Š<br />

V. D. Rosenthal, MD, MSc, CIC, a S. Guzman, RN, a and N. Safdar, MD b<br />

Buenos Aires, Argentina, and Madison, Wisconsin<br />

14 Background: Hand hygiene is a fundamental measure for the control of nosocomial infection. However, sustained compliance with<br />

15 hand hygiene in health care workers is poor. We attempted to enhance compliance with hand hygiene by implementing education,<br />

16 training, and performance feedback. We measured nosocomial infections in parallel.<br />

17 Methods: We monitored the overall compliance with hand hygiene during routine patient care in intensive care units (ICUs;<br />

18 1 medical surgical ICU and 1 coronary ICU) of 1 hospital in Buenos Aires, Argentina, before and during implementation of a hand<br />

19 ½Q3Š hygiene education, training, and performance feedback program. Observational surveys were done twice a week from September<br />

20 2000 to May 2002. Nosocomial infections in the ICUs were identified using the National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (NNIS)<br />

21 criteria, with prospective surveillance.<br />

22 Results: We observed 4347 opportunities for hand hygiene in both ICUs. Compliance improved progressively (handwashing<br />

23 adherence, 23.1% (268/1160) to 64.5% (2056/3187) (RR, 2.79; 95% CI: 2.46-3.17; P , .0001). During the same period, overall<br />

24 nosocomial infection in both ICUs decreased from 47.55 per 1000 patient-days (104/2187) to 27.93 per 1000 patient days (207/<br />

25 7409) RR, 0.59; 95% CI: 0.46-0.74, P , .0001).<br />

26 Conclusion: A program consisting of focused education and frequent performance feedback produced a sustained improvement in<br />

27 compliance with hand hygiene, coinciding with a reduction in nosocomial infection rates in the ICUs. (Am J Infect Control<br />

28 2005;n:nnn-nnn.)<br />

29 Nosocomial infections are associated with consid- In a previous study in Argentina, with education and 45<br />

44 mains elusive. 5 The study was conducted in 2 ICUs of a private, 180- 58<br />

30 erable morbidity, extra cost, and attributable mortality. performance feedback, adherence to hand hygiene 46<br />

31 We have previously reported a very high rate of improved considerably. 13 We noted disappointing 47<br />

32 nosocomial infection in Argentina. 1,2 Hand hygiene is compliance rates with hand hygiene in our institution 48<br />

33 a fundamental aspect of infection control, with several and developed a program consisting of focused, 49<br />

34 studies showing a decline in nosocomial infection rates frequent education of health care workers, emphasiz- 50<br />

35 when compliance with hand hygiene is enhanced. 3-8 ing adherence to published guidelines and perfor- 51<br />

36 Despite universal acknowledgement of the pivotal role mance feedback. We measured nosocomial infection 52<br />

37 that hand hygiene plays in reducing nosocomial rates at baseline 1 and during the intervention to 53<br />

38 infection, compliance among health care workers determine whether improved compliance would be 54<br />

39 remains poor, with rates ranging from 16% to 81%. 9-11 associated with a reduction in nosocomial infections. 55<br />

40 Numerous strategies have been attempted to enhance<br />

41 compliance with hand hygiene: some of which have<br />

42 resulted in improved short-term compliance 9,10,12 METHODS<br />

56<br />

;<br />

43 however, achievement of sustained improvement re- Setting<br />

57<br />

bed tertiary care teaching hospital situated in the city 59<br />

½Q1Š<br />

From the Section of Infectious Diseases and Hospital Epidemiology,<br />

Colegiales Hospital, Buenos Aires, Argentina a ; and the Section of<br />

Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, University of Wisconsin<br />

Medical School, Madison, WI. b<br />

Reprint requests:<br />

0196-6553/$30.00<br />

Copyright ª 2005 by the Association for Professionals in Infection<br />

Control and Epidemiology, Inc.<br />

doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2004.08.009<br />

of Buenos Aires. There is an infection control team<br />

composed of a medical doctor (with formal education<br />

and background in internal medicine, infectious diseases,<br />

and hospital epidemiology), an infection control<br />

nurse, and personnel support. 1 There is 1 medical<br />

surgical intensive care unit (12 beds) and 1 coronary<br />

intensive care unit (12 beds). Handwashing facilities<br />

are available, with 3 sinks in each intensive care unit<br />

with 4% chlorhexidine handwash dispensers and<br />

paper towels. The study proposal was submitted to<br />

<strong>UNCORRECTED</strong> <strong>PROOF</strong><br />

60<br />

61<br />

62<br />

63<br />

64<br />

65<br />

66<br />

67<br />

68<br />

69<br />

1<br />

FLA 5.0 DTD Š YMIC773_proof Š 30 June 2005 Š 3:42 pm

ARTICLE IN PRESS<br />

2 Vol. n No. n Rosenthal, Guzman, and Safdar<br />

70 the infection control committee, which included rep-<br />

71 resentative leadership of each hospital and ICU per-<br />

72 sonnel. The institutional review board at each center<br />

73 approved the study protocol. Patient confidentiality<br />

74 was protected by coding the recorded information only<br />

75 identifiable by infection control teams.<br />

76 Hand hygiene definition<br />

77 According with the last Guidelines for Hand Hygiene<br />

78 in Health-Care Settings, we defined hand hygiene as a<br />

79 general term that applies to either handwashing,<br />

80 antiseptic handwash, or antiseptic handrub. We de-<br />

81 fined handwashing as washing the hands with plain,<br />

82 nonantimicrobial soap and water. Antiseptic handrub<br />

83 was defined as a process when applying an antiseptic<br />

84 handrub product to all surfaces of the hands to reduce<br />

14<br />

85 ½Q4Š the number of microorganisms present.<br />

86 Hand hygiene intervention<br />

87 The hand hygiene program started in September<br />

88 2000. We divided the program into 2 phases: phase 1 (or<br />

89 baseline handwashing compliance), from September<br />

90 to December 2000 (4 months); and phase 2 (or inter-<br />

91 vention period), from January 2001 to May 2002 (17<br />

92 months). A comprehensive infection control manual<br />

93 was distributed to health care workers (HCW), and we<br />

94 used the Association for Professionals in Infection<br />

95 Control (APIC) hand hygiene guideline as an educational<br />

96 tool for this study. 15 Baseline and postintervention data<br />

97 regarding compliance of HCW with hand hygiene<br />

98 before contact with patients were collected in the ICUs<br />

99 by a trained infection control practitioner, who covertly<br />

100 observed the handwashing techniques of the health<br />

101 care workers at random times, including all shifts, for<br />

102 30-minute intervals during each phase of the study. Data<br />

103 on handwashing compliance including unit, shift, sex,<br />

104 and category of HCW (physician, nurse, and ancillary<br />

105 staff) were recorded on a specially designed form.<br />

106 Interventions to improve hand hygiene compliance<br />

107 included monthly meetings at which visual displays of<br />

108 handwashing rates were presented. These were also<br />

109 posted monthly in the 2 ICUs. Focused education of all<br />

110 HCWs was provided. Educational classes were given in<br />

111 1-hour group sessions for all shifts every day for 1 week.<br />

112 Each participant was given the infection control man-<br />

113 ual, and the APIC hand hygiene guideline was used as<br />

114 an educational tool to reinforce classroom teaching.<br />

115 Attendance was voluntary, supported by the admin-<br />

116 istrator, and monitored. Each HCW could attend the<br />

117 course as many times as desired. Theoretic and<br />

118 practical indications for the use of hand hygiene<br />

119 were reviewed. The guidelines were also posted at a<br />

120 strategic location in each ICU. Posttests to evaluate<br />

121 retention of educational material were given 1 month<br />

later. The primary investigator routinely held infection<br />

control review classes to provide an opportunity for<br />

infection control questions and share surveillance<br />

data. Frequent feedback was provided regarding hand<br />

hygiene rates and nosocomial infection rates, consisting<br />

of reports to the ICU manager and administrator,<br />

graphic presentations of hand hygiene rates displayed<br />

in meetings, and feedback data posted in the ICUs. We<br />

did not change soap or antibiotic use. The senior<br />

hospital management provided full administrative<br />

support for the study. No external funding was<br />

provided. The human resources for the intervention<br />

were those of the infection control program.<br />

Outcome measures<br />

<strong>UNCORRECTED</strong> <strong>PROOF</strong><br />

122<br />

123<br />

124<br />

125<br />

126<br />

127<br />

128<br />

129<br />

130<br />

131<br />

132<br />

133<br />

134<br />

135<br />

2002 with standardized methods.<br />

Hand hygiene compliance was observed simulta- 136<br />

neously along with multiple other infection control 137<br />

responsibilities in the ICU. The infection control 138<br />

program is well-known by the ICU staff, and, although 139<br />

the HCWs were informed that their hand hygiene 140<br />

practices were being monitored, the staff was not 141<br />

aware of precisely when these observations were being 142<br />

made. We commenced education on January 2001 and 143<br />

started performance feedback on May 2001, after 144<br />

which HCWs were aware that their hand hygiene 145<br />

practices were being monitored. Trained staff observed 146<br />

the handwashing technique of physicians, nursing 147<br />

staff, and technicians at random times twice a week, 148<br />

including all work shifts for 30-minute intervals during 149<br />

each phase of the study.<br />

150<br />

The contacts were monitored with direct observa- 151<br />

tion, and the infection control practitioners (ICPs) 152<br />

recorded the handwashing processes before contact 153<br />

with each patient. One nurse was trained to detect 154<br />

handwashing compliance and to record it on a form 155<br />

designed for the study. To provide feedback, bar charts 156<br />

of handwashing rates were displayed at monthly 157<br />

meetings and posted each month in the ICUs.<br />

158<br />

Nococomial infections were identified by a trained 159<br />

infection control nurse in the ICUs according to 160<br />

adapted standard definitions of the Centers for Disease 161<br />

Control and Prevention. 16 The ICP obtained such 162<br />

information from the medical records nurse charts, 163<br />

microbiology laboratory reports, and other laboratory 164<br />

results, including white cell counts, radiographs, and 165<br />

other available studies. We followed the patients for 48 ½Q5Š 166<br />

hours after discharge from the ICUs. Prospective 167<br />

surveillance for nosocomial infections has been car- 168<br />

ried out in our hospital since September 2000 to May<br />

169<br />

170<br />

Nosocomial infection definitions<br />

171<br />

Ventilator-associated pneumonia. Criterion 1: a<br />

mechanically ventilated patient has rales or dullness<br />

172<br />

173<br />

FLA 5.0 DTD Š YMIC773_proof Š 30 June 2005 Š 3:42 pm

ARTICLE IN PRESS<br />

Rosenthal, Guzman, and Safdar n 2005 3<br />

174 to percussion on physical examination of the chest and<br />

175 at least 1 of the following: new onset of purulent<br />

176 sputum or change in character of sputum; organism<br />

177 cultured from blood; isolation of an etiologic agent<br />

178 from a specimen obtained by transtracheal aspirate,<br />

179 bronchial brushing, or biopsy. 16<br />

180 Criterion 2: a mechanically ventilated patient has<br />

181 a chest radiographic examination that shows a new<br />

182 or progressive infiltrate, consolidation, cavitation, or<br />

183 pleural effusion and at least 1 of the following: new<br />

184 onset of purulent sputum or change in character of<br />

185 sputum; organism cultured from blood; isolation of an<br />

186 etiologic agent from a specimen obtained by trans-<br />

187 tracheal aspirate, bronchial brushing, or biopsy; or<br />

188 histopathologic evidence of pneumonia. 16<br />

189 Laboratory-confirmed, catheter-associated blood-<br />

190 stream infection. A patient with a central venous<br />

191 catheter has a recognized pathogen cultured from 1 or<br />

192 more percutaneous blood cultures, after 48 hours of<br />

193 vascular catheterization, and the pathogen cultured<br />

194 from the blood is not related to an infection at another<br />

195 site and patient has at least 1 of the following signs or<br />

196 symptoms: fever ($38°C), chills, or hypotension. With<br />

197 common skin commensals (eg, diphtheroids, Bacillus<br />

198 species, Propionibacterium species, coagulase-nega-<br />

199 tive staphylococci, or micrococci), the organism is<br />

200 cultured from 2 or more blood cultures drawn on<br />

201 separate occasions. 16<br />

202 Clinically suspected, catheter-associated blood-<br />

203 stream infection. A patient with a central venous<br />

204 catheter has at least 1 of the following clinical signs,<br />

205 with no other recognized cause: fever ($38°C), hypo-<br />

206 tension (systolic blood pressure #90 mm Hg), or<br />

207 oliguria (#20 mL/hr); but blood cultures were not<br />

208 obtained or no organisms were recovered from blood<br />

209 cultures, but there is no apparent infection at another<br />

210 site and the physician institutes treatment. 16<br />

211 Symptomatic catheter-associated urinary tract in-<br />

212 fection. Criterion 1: A patient with a foley urinary<br />

213 catheter has 1 or more of the following with no other<br />

214 recognized cause: fever ($38°C), urgency, frequency,<br />

215 or suprapubic tenderness, and the urine culture is<br />

216 positive for $10 5 CFU/mL with no more than 2<br />

217 microorganisms. 16<br />

218 Criterion 2: A patient with a foley urinary catheter<br />

219 has at least 2 of the following signs of infection with<br />

220 no other recognized cause: positive dipstick for<br />

221 leukocyte esterase and/or nitrate; pyuria ($10 WBC/<br />

222 mL); organisms are seen on Gram’s stain; physician<br />

223 diagnoses a urinary tract infection; or physician<br />

224 initiates appropriate therapy for a urinary tract<br />

225 infection. 16 Nosocomial infection rates were calcu-<br />

226 lated by dividing the total number of nosocomial<br />

227 infections by the number of patient-days and multi-<br />

228 plied by 1000.<br />

Statistical analysis<br />

Our a priori hypothesis was that we could increase<br />

hand hygiene compliance to 70%, with reduction in<br />

nosocomial infection by 30% in keeping with results of<br />

the SENIC study. 18 Differences in proportions were<br />

compared by x 2 tests providing relative risk, corresponding<br />

95% confidence intervals, and P value.<br />

Changes in compliance over time were estimated in a<br />

univariate analysis with the first survey as the reference<br />

point (Epi Info, version 6.04b, Centers for Disease<br />

Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA). Two-tailed P<br />

values of less than .05 were considered to indicate<br />

statistical significance.<br />

RESULTS<br />

<strong>UNCORRECTED</strong> <strong>PROOF</strong><br />

229<br />

230<br />

231<br />

232<br />

233<br />

234<br />

235<br />

236<br />

237<br />

238<br />

239<br />

240<br />

241<br />

242<br />

Between September 2000 and May 2002, we 243<br />

obtained data on a total of 4347 opportunities for 244<br />

hand hygiene ( Table 1). The baseline phase (or phase 1) ½T1Š245<br />

was from September 2000 to December 2000 (4 246<br />

months), and the intervention phase (or phase 2) was 247<br />

from January 2001 to May 2002 (17 months). Overall 248<br />

compliance improved from 23.1% in phase 1 to 64.5% 249<br />

in phase 2 (RR, 2.79; 95% CI: 2.46-3.17; P , .0001) 250<br />

(Table 1).<br />

251<br />

Divided into 4 periods, period 1 (from September to 252<br />

December 2000), period 2 (from January to June 2001), 253<br />

period 3 (from July to December 2001) and period 4 254<br />

(from January to May 2002), we found that the 255<br />

compliance was higher comparing period 2 (724/ 256<br />

1353, 53.5%) with period 1 (268/1160, 23.1%) (RR, 257<br />

2.32; 95% CI: 2.01-2.66; P = .0000). The compliance 258<br />

was higher comparing period 3 (828/1148, 72.1%) with 259<br />

period 2 (724/1353, 53.5%) (RR, 1.35; 95% CI: 1.22- 260<br />

1.49; P = .0000). The compliance was similar com- 261<br />

paring period 4 (518/701, 73.8%) with period 3 (828/ 262<br />

1148, 72.1%) (RR, 1.02; 95% CI: 0.92-1.14, P = .665) ½Q6Š 263<br />

( Table 2).<br />

½T2Š264<br />

The compliance was higher for nurses (59.6%) 265<br />

compared with physicians (30.8%) (RR, 1.31; 95% CI: 266<br />

1.11-1.54; P = .0012). The compliance was higher for ½Q7Š 267<br />

nurses (59.6%) compared with ancillary staff (37.1%) 268<br />

(RR, 1.39; 95% CI: 1.18-1.64; P , .0001). The compli- 269<br />

ance was similar for physicians (30.8%) compared 270<br />

with ancillary staff (37.1%) (RR, 0.94; 95% CI: 0.76- 271<br />

1.17; P = .6010). The compliance was higher for 272<br />

women (57.8%) compared with men (43.2%) (RR, 273<br />

1.23; 95% CI: 1.09-1.38; P = .0005). The compliance 274<br />

was higher for superficial (56.7%) compared with 275<br />

invasive procedures (48.1%) (RR, 1.21; 95% CI: 1.08- 276<br />

1.35; P = .0008). The compliance was higher during 277<br />

the night work shift (66.0%) compared with afternoon 278<br />

work shift (50.2%) (RR, 1.18; 95% CI: 1.02-1.37; 279<br />

P = .02). The compliance was similar during the night 280<br />

FLA 5.0 DTD Š YMIC773_proof Š 30 June 2005 Š 3:42 pm

ARTICLE IN PRESS<br />

4 Vol. n No. n Rosenthal, Guzman, and Safdar<br />

Table 1. Improvement in compliance rates in 2 phases<br />

Year Opportunities for hand hygiene Observed handwashing episodes Adherence (%) RR 95% CI P value<br />

2000 1160 268 23.1% 2.79 2.46-3.17 ,.0001<br />

2001-2002 3187 2056 64.5%<br />

Table 2. Improvement in compliance rates in 4 phases<br />

Period Year Months Opportunities for HH Observed HH episodes HH adherence (%) RR 95% CI P value<br />

1 2000 9-12 1160 268 23.10<br />

2 2001 1-6 1353 724 53.5 1 vs 2 = 2.32 2.01-2.66 .0000<br />

3 2001 7-12 1148 828 72.1 2 vs 3 = 1.35 1.22-1.49 .0000<br />

4 2002 1-5 701 518 73.8 3 vs 4 = 1.02 0.92-1.14 .665<br />

HH, hand hygiene.<br />

281 work shift (66.0%) and morning work shift (52.2%)<br />

282 (RR, 1.08; 95% CI: 0.93-1.25; P = .294). The compli-<br />

283 ance was similar during the morning work shift<br />

284 (52.2%) compared with afternoon work shift (50.2%)<br />

285 (RR, 1.09; 95% CI: 0.97-1.23; P = .1420). The compli-<br />

286 ance was similar for medical surgical ICU (53.5%)<br />

287 compared with coronary care unit (53.6) (RR, 1.0; 95%<br />

288 ½T3Š CI: 0.9-1.11; P = .97) ( Table 3). During the same period,<br />

289 overall nosocomial infection in both ICUs decreased<br />

290 from 47.55 per 1000 patient-days (104/2187) to 27.93<br />

291 per 1000 patient days (207/7409) (RR, 0.59; 95% CI:<br />

292 ½T4Š 0.46-0.74; P , .0001) ( Table 4).<br />

293 DISCUSSION<br />

294 A large body of literature exists on the challenging<br />

295 task of achieving compliance with hand-hygiene rec-<br />

296 ommendations in the health care setting. Pittet et al<br />

297 studied predictors of noncompliance with hand hy-<br />

298 giene in an observational study and found that, in<br />

299 multivariate analysis, physicians and nursing assistants<br />

300 had lower compliance rates than nurses. Of concern,<br />

301 compliance was lower in ICUs and during procedures<br />

302 that carried a high risk of contamination. 19 In a more<br />

303 recent cross-sectional survey of 163 physicians, the<br />

304 same investigators reported that adherence to hand<br />

305 hygiene was associated with awareness of being<br />

306 observed and ready availability of handrubs. Gaps in<br />

307 knowledge regarding guidelines and the importance of<br />

308 hand hygiene is another barrier reported in the<br />

309 literature. 20 Larson et al have reported some perceived<br />

310 barriers include ignorance of the importance and<br />

311 impact of hand hygiene and lack of information<br />

312 regarding the existence of published guidelines. 21<br />

313 Several interventions have been attempted to improve<br />

314 hand hygiene practices; among the most effective have<br />

315 been those that emphasize targeted education and<br />

316 frequent performance feedback. 10,22-25 Dubbert et al<br />

317 found that, although education alone improved com-<br />

318 pliance rates transiently, performance feedback re-<br />

<strong>UNCORRECTED</strong> <strong>PROOF</strong><br />

to 40% in the follow-up period.<br />

represent an ongoing challenge to improve.<br />

sulted in a more sustained improvement in 319<br />

compliance 10 ; rates of infection were, however, not 320<br />

reported in this study. More recently, patient education 321<br />

has received attention as a possible means of improv- 322<br />

ing adherence to hand hygiene in HCWs. In a pre- and 323<br />

postintervention study in an inpatient rehabilitation 324<br />

unit, McGuckin et al used a patient education model 325<br />

consisting of patients asking HCWs coming into con- 326<br />

tact with them whether they had washed their hands. 327<br />

Compliance (measured through soap/sanitizer usage 328<br />

per resident-day) improved to 94% during the 6-week 329<br />

intervention. However, adherence to hand hygiene fell<br />

330<br />

331<br />

Our study expands the current body of literature by 332<br />

showing the impact of a relatively low-cost strategy– 333<br />

education and performance feedback–in not only 334<br />

increasing adherence to hand hygiene but also a 335<br />

decline in nosocomial infection in a developing coun- 336<br />

try and is the first showing reduction of nosocomial 337<br />

infection by improving hand hygiene in Latin America. 338<br />

We found a 42% relative reduction in nosocomial 339<br />

infection rates by emphasizing compliance with hand 340<br />

hygiene. Our results are in keeping with those of other 341<br />

studies that reported a considerable decline in noso- 342<br />

comial infections after enhanced compliance with 343<br />

hand hygiene. 4,6 We found lower adherence among 344<br />

physicians, and during invasive procedures, which is 345<br />

similar to the results reported by Pittet et al and<br />

346<br />

347<br />

In our study, we did not make a change in the choice 348<br />

of hand hygiene agent. Prior randomized trials using 349<br />

nosocomial infections as the outcome measure have 350<br />

found that handwashing with 2% to 4% chlorhexidine 351<br />

is associated with lower rates of nosocomial infec- 352<br />

tion. 4,27,28 More recently, the use of alcohol-based 353<br />

hand sanitizers has become widespread. Alcohol-based 354<br />

handrubs are recommended in the most recent CDC 355<br />

hand hygiene guideline 29 and have been associated 356<br />

with increased compliance with hand hygiene and, in 357<br />

some studies, lower nosocomial infection rates. 5,6 358<br />

FLA 5.0 DTD Š YMIC773_proof Š 30 June 2005 Š 3:42 pm

ARTICLE IN PRESS<br />

Rosenthal, Guzman, and Safdar n 2005 5<br />

Table 3. Adherence to hand hygiene<br />

Variable Opportunities for HH Observed HH episodes Adherence (%) RR 95% CI P value<br />

MS-ICU 1271 680 53.5 MS-ICU vs CO-CU = 1.0 0.9-1.11 .97<br />

CO-CU 1293 693 53.6<br />

Women 1701 972 57.8 Women vs men = 1.23 1.09-1.38 .0005<br />

Men 862 401 43.2<br />

Nurse 1806 1047 59.6 Nurse vs physician = 1.31 1.11-1.54 .001<br />

Physician 375 166 30.8<br />

Ancillary staff 383 160 37.1<br />

Superficial 1534 882 56.7 Superfic vs invas = 1.21 1.08-1.35 .0008<br />

Invasive 1030 491 48.1<br />

Night 428 253 66.0 Night vs morning = 1.18 1.02-0.37 .02<br />

Morning 1107 605 52.2<br />

Afternoon 1029 515 50.2<br />

MS-ICU, medical surgical intensive care unit; CO-CU, coronary care unit; superfic, superficial contact; invas, invasive contact; HH, hand hygiene.<br />

Table 4. Nosocomial infections distribution by phase<br />

Phase 1 2 RR 95% CI P value<br />

Period September 2000-December 2000 January 2001-May 2002<br />

Central vascular catheter-associated LCBI 15 12<br />

Central vascular catheter-associated CSEP 21 11<br />

Peripheral vascular catheter-associated LCBI 3 4<br />

Peripheral vascular catheter-associated CSEP 1 2<br />

Ventilator-associated pneumonia 29 69<br />

Pnuemonia not associated to ventilator 10 51<br />

Catheter-associated UTI 25 56<br />

UTI not associated to catheter 0 2<br />

Total nosocomial infections 104 207<br />

Bed days 2187 7409<br />

Nosocomial infections per 1000 bed days 47.55 27.93 0.59 0.46-0.74 .0000<br />

½Q9Š LCBI, Laboratory confirmed bloodstream infections; CSEP, clinical sepsis; UTI, urinary tract infection.<br />

359 Our study has several limitations. This was not a<br />

360 randomized study; randomization of hand hygiene<br />

361 versus no hand hygiene is not feasible because of<br />

362 ethical reasons and the recognized value of handwash-<br />

363 ing. The Hawthorne effect must be taken into consid-<br />

364 eration in every behavioral study in which a short-term<br />

365 impact of the intervention may be seen as a result of<br />

366 behavior change stemming from being observed. The<br />

367 relatively long follow-up period of our study and<br />

368 demonstration of sustained improvement in hand<br />

369 hygiene adherence make this effect less of a concern.<br />

370 Its quasiexperimental design and implementation of<br />

371 other simultaneous specific infection control interven-<br />

372 tions to reduce CVC-associated bloodstream infec-<br />

373 tions, 30 and urinary catheter-associated UTIs, 31 make<br />

374 the true impact of the hand hygiene program difficult<br />

375 to assess.<br />

376 Our results have, in part, been published in 2<br />

377 previous reports, one reporting on rates of catheter-<br />

378 associated UTI, 31 which overlapped for 17 of 21 months<br />

379 with the present study and the other reporting rates of<br />

380 CVC-associated bloodstream infections, 30 which over-<br />

381 lapped for 7 of 21 months with the present study. These<br />

2 previous studies analyzed only catheter-associated<br />

UTI and CVC-associated bloodstream infections. We<br />

expand these results in our current study to include the<br />

effect of hand hygiene on the following nosocomial<br />

infections beyond those but including those previously<br />

reported: ventilator-associated pneumonia, nosocomial<br />

pneumonia not associated with ventilators, central<br />

vascular catheter-associated bloodstream infections,<br />

peripheral vascular catheter-associated bloodstream<br />

infections, catheter-associated UTI, and UTI not associated<br />

with catheterization. The performance feedback<br />

was effective in achieving increased adherence to hand<br />

hygiene; however, this strategy requires considerable<br />

institutional commitment and environmental changes<br />

to enhance compliance.<br />

In conclusion, our study shows that a program<br />

focused on education and performance feedback of<br />

HCWs is effective in promoting hand hygiene and<br />

lowering nosocomial infection rates. Although institutional<br />

support and frequent observation is required for<br />

such a program to be successful, it is a relatively lowcost<br />

approach that may be especially attractive in<br />

developing countries.<br />

<strong>UNCORRECTED</strong> <strong>PROOF</strong><br />

382<br />

383<br />

384<br />

385<br />

386<br />

387<br />

388<br />

389<br />

390<br />

391<br />

392<br />

393<br />

394<br />

395<br />

396<br />

397<br />

398<br />

399<br />

400<br />

401<br />

402<br />

403<br />

404<br />

FLA 5.0 DTD Š YMIC773_proof Š 30 June 2005 Š 3:42 pm

ARTICLE IN PRESS<br />

6 Vol. n No. n Rosenthal, Guzman, and Safdar<br />

405 References<br />

406 1. Rosenthal VD, Guzman S, Crnich C. Device-associated nosocomial<br />

407 infection rates in intensive care units of Argentina. Infect Control<br />

408 Hosp Epidemiol 2004;25:251-5.<br />

409 2. Rosenthal VD, Guzman S, Orellano PW, Safdar N. Nosocomial<br />

410 infections in medical-surgical intensive care units in Argentina:<br />

411 attributable mortality and length of stay. Am J Infect Control 2003;<br />

412 31:291-5.<br />

413 3. Larson E. Skin hygiene and infection prevention: more of the same or<br />

414 different approaches? Clin Infect Dis 1999;29:1287-94.<br />

415 ½Q8Š 4. Doebbeling BN, Stanley GL, Sheetz CT, et al. Comparative efficacy of<br />

416 alternative hand-washing agents in reducing nosocomial infections in<br />

417 intensive care units. N Engl J Med 1992;327:88-93.<br />

418 5. Pittet D, Hugonnet S, Harbarth S, et al. Effectiveness of a hospital-wide<br />

419 programme to improve compliance with hand hygiene: Infection<br />

420 Control Programme. Lancet 2000;356:1307-12.<br />

421 6. Fendler EJ, Ali Y, Hammond BS, Lyons MK, Kelley MB, Vowell NA. The<br />

422 impact of alcohol hand sanitizer use on infection rates in an extended<br />

423 care facility. Am J Infect Control 2002;30:226-33.<br />

424 7. Zafar AB, Butler RC, Reese DJ, Gaydos LA, Mennonna PA. Use of<br />

425 0.3% triclosan (Bacti-Stat) to eradicate an outbreak of methicillin-<br />

426 resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a neonatal nursery. Am J Infect<br />

427 Control 1995;23:200-8.<br />

428 8. Casewell M, Phillips I. Hands as route of transmission for Klebsiella<br />

429 species. Br Med J 1977;2:1315-7.<br />

430 9. Pittet D. Improving adherence to hand hygiene practice: a multidis-<br />

431 ciplinary approach. Emerg Infect Dis 2001;7:234-40.<br />

432 10. Dubbert PM, Dolce J, Richter W, Miller M, Chapman SW. Increasing<br />

433 ICU staff handwashing: effects of education and group feedback. Infect<br />

434 Control Hosp Epidemiol 1990;11:191-3.<br />

435 11. Donowitz LG. Handwashing technique in a pediatric intensive care<br />

436 unit. Am J Dis Child 1987;141:683-5.<br />

437 12. Larson EL, Bryan JL, Adler LM, Blane C. A multifaceted approach to<br />

438 changing handwashing behavior. Am J Infect Control 1997;25:3-10.<br />

439 13. Rosenthal VD, McCormick RD, Guzman S, Villamayor C, Orellano<br />

440 PW. Effect of education and performance feedback on handwashing:<br />

441 the benefit of administrative support in Argentinean hospitals. Am J<br />

442 Infect Control 2003;31:85-92.<br />

443 14. Boyce JM, Pittet D. Guideline for hand hygiene in health-care settings:<br />

444 recommendations of the health care infection control practices<br />

445 advisory committee and the hicpac/shea/apic/idsa hand hygiene task<br />

446 force. Am J Infect Control 2002;30:1-46.<br />

447 15. Larson EL. APIC guideline for handwashing and hand antisepsis in<br />

448 health care settings. Am J Infect Control 1995;23:251-69.<br />

449 16. Garner JS, Jarvis WR, Emori TG, Horan TC, Hughes JM. CDC<br />

450 definitions for nosocomial infections, 1988. Am J Infect Control 1988;<br />

451 16:128-40.<br />

<strong>UNCORRECTED</strong> <strong>PROOF</strong><br />

17. Emori TG, Culver DH, Horan TC, et al. National nosocomial 452<br />

infections surveillance system (NNIS): description of surveillance 453<br />

methods. Am J Infect Control 1991;19:19-35.<br />

454<br />

18. Haley RW, Morgan WM, Culver DH, et al. Update from the SENIC 455<br />

project. Hospital infection control: recent progress and opportunities 456<br />

under prospective payment. Am J Infect Control 1985;13:97-108. 457<br />

19. Pittet D, Mourouga P, Perneger TV. Compliance with handwashing in a 458<br />

teaching hospital. Infection Control Program. Ann Intern Med 1999; 459<br />

130:126-30.<br />

460<br />

20. Pittet D. Improving compliance with hand hygiene in hospitals. Infect 461<br />

Control Hosp Epidemiol 2000;21:381-6.<br />

462<br />

21. Larson E, Kretzer EK. Compliance with handwashing and barrier 463<br />

precautions. J Hosp Infect 1995;30:88-106.<br />

464<br />

22. van de Mortel T, Bourke R, Fillipi L, et al. Maximising handwashing 465<br />

rates in the critical care unit through yearly performance feedback. 466<br />

Aust Crit Care 2000;13:91-5.<br />

467<br />

23. Tibballs J. Teaching hospital medical staff to handwash. Med J Aust 468<br />

1996;164:395-8.<br />

469<br />

24. Aspock C, Koller W. A simple hand hygiene exercise. Am J Infect 470<br />

Control 1999;27:370-2.<br />

471<br />

25. Colombo C, Giger H, Grote J, et al. Impact of teaching interventions 472<br />

on nurse compliance with hand disinfection. J Hosp Infect 2002;51: 473<br />

69-72.<br />

474<br />

26. McGuckin M, Taylor A, Martin V, Porten L, Salcido R. Evaluation of a 475<br />

patient education model for increasing hand hygiene compliance in an 476<br />

inpatient rehabilitation unit. Am J Infect Control 2004;32:235-8. 477<br />

27. Massanari RM, Hierholzer WJ. A crossover comparison of antiseptic 478<br />

soaps on nosocomial infection rates in intensive care units. Am J Infect 479<br />

Control 1984;12:247.<br />

480<br />

28. Maki DG, Hecht J. Antiseptic-containing hand-washing agents reduce 481<br />

nosocomial infections: a prospective study. Proceedings and abstracts 482<br />

of the Twenty Second Interscience Conference of Antimicrobial 483<br />

Agents and Chemotherapy, Miami, October 4-6, 1982. Washington, 484<br />

DC: American Society for Microbiology.<br />

485<br />

29. Boyce JM, Pittet D. Guideline for Hand Hygiene in Health-Care 486<br />

Settings: recommendations of the Healthcare Infection Control 487<br />

Practices Advisory Committee and the HICPAC/SHEA/APIC/IDSA 488<br />

Hand Hygiene Task Force. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2002;23: 489<br />

S3-40.<br />

490<br />

30. Rosenthal VD, Guzman S, Pezzotto SM, Crnich CJ. Effect of an 491<br />

infection control program using education and performance feedback 492<br />

on rates of intravascular device-associated bloodstream infections in 493<br />

intensive care units in Argentina. Am J Infect Control 2003;31:405-9. 494<br />

31. Rosenthal VD, Guzman S, Safdar N. Effect of education and 495<br />

performance feedback on rates of catheter-associated urinary tract 496<br />

infection in intensive care units in Argentina. Infect Control Hosp 497<br />

Epidemiol 2004;25:47-50.<br />

498<br />

499<br />

FLA 5.0 DTD Š YMIC773_proof Š 30 June 2005 Š 3:42 pm