Architect 2014-03.pdf

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

AIAFEATURE<br />

45<br />

march <strong>2014</strong><br />

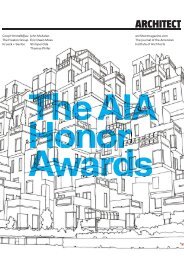

1922 Tribune Tower competition (left to right): entries by Bertram Goodhue; Bruno Taut,<br />

Walter Gunther, and Kurz Schutz; and Walter Gropius. Opposite: Eliel Saarinen’s second<br />

prize entry (with Chicago architects Dwight Wallace and Bertell Grenman).<br />

an architectural competition can be an adrenalin rush.<br />

Just imagine hundreds of designers, from the famous to the<br />

wet-behind-the-ears, all thinking about the same program, all<br />

simultaneously striving to improve the commonweal with a brilliant<br />

solution to a major urban problem—or at least designing an icon that<br />

will change their careers forever.<br />

A competition is an opportunity for an untried visionary to sweep<br />

away the Old Guard and offer a transformative paradigm. Maya Lin,<br />

a Yale undergraduate in 1981 when she beat out 1,441 other entrants<br />

to design the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C.,<br />

epitomizes that dream. Her controversial incision in the landscape<br />

on the National Mall changed how we approach commemorative<br />

public monuments. “Competitions are the province of the young and<br />

the unemployed,” says Andrus Burr, FAIA, a Williamstown, Mass.,<br />

architect and Lin’s critic for the competition project at Yale.<br />

“Superstars are too busy to enter competitions,” says Helsinki<br />

architect Mikko Heikkinen, Hon. FAIA, whose firm, Heikkinen-<br />

Komonen <strong>Architect</strong>s, got its big start by winning a competition.<br />

While that is not always true, there’s a kind of idealism and youthful<br />

ardor that fuels stories like Lin’s and is the basis of hundreds of socalled<br />

“ideas competitions” that happen each year.<br />

In a similar manner, Joseph Paxton, an architect and gardener,<br />

came up with a giant greenhouse to house the world’s first<br />

international exposition in London’s Hyde Park in 1851. The Crystal<br />

Palace revolutionized the nature of large structures through<br />

prefabrication, among other achievements. The other contenders,<br />

with their Gothic peaks and massive brick domes, were rendered<br />

mute by the simplicity of Paxton’s ferrovitreous cathedral.<br />

Some students learn about legendary competitions, such as that<br />

for the Tribune Tower in Chicago in 1922, for which a Gothic Revival<br />

design by the New York architects John Mead Howells and Raymond<br />

Hood beat out the likes of Walter Gropius and Eliel Saarinen, who<br />

both submitted spare, modern takes on monumental commercial<br />

architecture. (This introduces us to the myth of more accomplished<br />

but slighted designers who deserved to win. If one placed second in<br />

a competition, one could avoid the headaches of construction while<br />

preserving an unassailable position of superiority.) Several years<br />

later, Saarinen was notified that he had won the contest to build<br />

Gateway Arch in St. Louis, only to be subsequently informed that it<br />

was his son, Eero, who had secured that plum commission. A story<br />

like that is closer to Shakespearean tragedy than to the everyday<br />

drudgery of office work.<br />

The competition process is often fraught with difficulty,<br />

especially when a project is both very public and extremely<br />

significant (think of the recent Eisenhower Memorial in Washington,<br />

D.C., or the suite of buildings at Ground Zero in New York). Danish<br />

architect Jørn Utzon gave a continent an instantly recognizable<br />

signature with his winning design for the Sydney Opera House (juror