BIRD FLU a virus of our own hatching

BIRD FLU a virus of our own hatching

BIRD FLU a virus of our own hatching

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

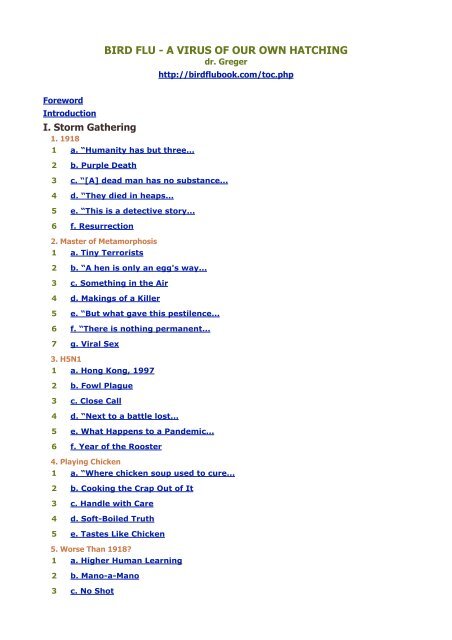

<strong>BIRD</strong> <strong>FLU</strong> - A VIRUS OF OUR OWN HATCHING<br />

dr. Greger<br />

http://birdflubook.com/toc.php<br />

Foreword<br />

Introduction<br />

I. Storm Gathering<br />

1. 1918<br />

1 a. “Humanity has but three...<br />

2 b. Purple Death<br />

3 c. “[A] dead man has no substance...<br />

4 d. “They died in heaps...<br />

5 e. “This is a detective story...<br />

6 f. Resurrection<br />

2. Master <strong>of</strong> Metamorphosis<br />

1 a. Tiny Terrorists<br />

2 b. “A hen is only an egg's way...<br />

3 c. Something in the Air<br />

4 d. Makings <strong>of</strong> a Killer<br />

5 e. “But what gave this pestilence...<br />

6 f. “There is nothing permanent...<br />

7 g. Viral Sex<br />

3. H5N1<br />

1 a. Hong Kong, 1997<br />

2 b. Fowl Plague<br />

3 c. Close Call<br />

4 d. “Next to a battle lost...<br />

5 e. What Happens to a Pandemic...<br />

6 f. Year <strong>of</strong> the Rooster<br />

4. Playing Chicken<br />

1 a. “Where chicken soup used to cure...<br />

2 b. Cooking the Crap Out <strong>of</strong> It<br />

3 c. Handle with Care<br />

4 d. S<strong>of</strong>t-Boiled Truth<br />

5 e. Tastes Like Chicken<br />

5. Worse Than 1918?<br />

1 a. Higher Human Learning<br />

2 b. Mano-a-Mano<br />

3 c. No Shot

4 d. Bitter Pill<br />

5 e. Pr<strong>of</strong>it Motive<br />

6 f. Population Bust<br />

7 g. “Get rid <strong>of</strong> the ‘if.’...<br />

6. When, Not If<br />

1 a. “It is coming.”<br />

2 b. Two Minutes to Midnight<br />

3 c. Flu Year’s Eve<br />

4 d. Catching the Flu<br />

5 e. Boots on the Ground<br />

II. When Animal Viruses Attack<br />

1. The Third Age<br />

1 a. Emerging Infectious Disease<br />

2 b. Their Bugs Are Worse...<br />

3 c. “Most and probably all...<br />

4 d. “Wherever the European has trod...<br />

5 e. The Plague Years<br />

2. Man Made<br />

1 a. AIDS: A Clear-Cut Disaster<br />

2 b. Aggressive Symbiosis<br />

3 c. Wild Tastes<br />

4 d. Shipping Fever<br />

5 e. America’s S<strong>of</strong>t Underbelly<br />

6 f. Pet Peeves<br />

7 g. Pigs Barking Blood<br />

3. Livestock Revolution<br />

1 a. Breeding Grounds<br />

2 b. Back to the Dark Ages<br />

3 c. Stomaching Emerging Disease<br />

4 d. Offal Truth<br />

5 e. Big Mac Attack<br />

6 f. Animal Bugs Forced to Join...<br />

7 g. Last Great Plague<br />

4. Tracing the Flight Path<br />

1 a. Pandora’s Pond<br />

2 b. Hog Ties<br />

3 c. Viral Swap Meets<br />

4 d. Gambling with Our Lives?

5 e. Stopping Traffic<br />

5. One Flu Over the Chicken’s Nest<br />

1 a. Acute Life Strategy<br />

2 b. “In <strong>our</strong> efforts to streamline...<br />

3 c. Chicken Surprise<br />

4 d. Out <strong>of</strong> the Trenches<br />

5 e. A Chicken in Every Pot<br />

6 f. “You have to say...<br />

6. Coming Home to Roost<br />

1 a. Overcrowded<br />

2 b. Stressful<br />

3 c. Filthy<br />

4 d. Lack <strong>of</strong> Sunlight<br />

5 e. Bred to Be Sick<br />

6 f. Monoculture<br />

7 g. Acquired Immunodeficiency...<br />

7. Guarding the Henhouse<br />

1 a. Chicken Run<br />

2 b. Wishful Thinking<br />

3 c. Made in the USA<br />

III. Pandemic Preparedness<br />

1. Cooping Up Bird Flu<br />

1 a. Taming <strong>of</strong> the Flu<br />

2 b. Thai Curry Favor with Poultry...<br />

3 c. “We have as much chance...<br />

2. Race Against Time<br />

1 a. “He who desires, but acts not...<br />

2 b. Chicken Little Gets the Flu<br />

3 c. Our Best Shot<br />

3. Tamiflu<br />

1 a. “Access to medicines...<br />

2 b. Patent Nonsense<br />

3 c. End <strong>of</strong> the Line<br />

4 d. “The success or failure...<br />

5 e. Don't Need a Hurricane to Know...<br />

IV. Surviving the Pandemic<br />

1. Don’t Wing It<br />

1 a. The A List

2 b. Stretching the Stockpile<br />

3 c. Get It Now While Supplies Last<br />

4 d. Crash C<strong>our</strong>se<br />

2. Our Health in Our Hands<br />

1 a. Coming Soon to a Theater Near You<br />

2 b. Coughs and Sneezes...<br />

3 c. Washing Y<strong>our</strong> Hands <strong>of</strong> the Flu<br />

4 d. There’s the Rub<br />

5 e. Masking Our Ignorance<br />

3. Be Prepared<br />

1 a. Home Health Aid<br />

2 b. Collateral Damage<br />

3 c. Corpse Management<br />

4 d. Bird Flu Vultures Lining Up<br />

5 e. “We have learned very little...<br />

6 f. “In the absence <strong>of</strong> a pandemic...<br />

V. Preventing Future Pandemics<br />

1. Tinderbox<br />

1 a. Trojan Duck<br />

2 b. One Stray Spark<br />

3 c. Biosafety Level Zero<br />

4 d. Snowflakes to an Avalanche<br />

5 e. Worst <strong>of</strong> Both Worlds<br />

2. Reining in the Pale Horse<br />

1 a. “Extreme remedies...<br />

2 b. “The modern world...<br />

3 c. “The single biggest threat...<br />

4 d. In a Flap<br />

5 e. The Price We Pay<br />

Topics<br />

References

Foreword<br />

by Kennedy Shortridge, PhD, DSc(Hon), CBiol, FIBiol<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Emeritus Kennedy Shortridge<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Emeritus Kennedy Shortridge is credited for having first discovered the H5N1 <strong>virus</strong> in Asia. As<br />

chair <strong>of</strong> the Department <strong>of</strong> Microbiology at the University <strong>of</strong> Hong Kong, Dr. Shortridge led the world’s<br />

first fight against the <strong>virus</strong>. For his pioneering work studying flu <strong>virus</strong>es, which spans over three decades,<br />

he was awarded the highly prestigious Prince Mahidol Award in Public Health, considered the “Nobel Prize<br />

<strong>of</strong> Asia.”<br />

Horse-drawn carts piled with dead bodies circulated through a small t<strong>own</strong> in Queensland,<br />

Australia. A nightmare to imagine, yet even more horrific to learn that this scene was a<br />

recurring reality throughout the world during the 1918–1919 influenza pandemic.<br />

My mother’s compelling stories about the devastating reaches <strong>of</strong> the pandemic have stayed<br />

with me since my earliest years. What started out as a spark <strong>of</strong> interest has led me to search<br />

the hows and whys <strong>of</strong> influenza pandemics through birds and mammals.<br />

The world has seen unprecedented advances in science and technology over the past 50 years,<br />

and, with it, a phenomenal increase in the availability <strong>of</strong> food, especially meat protein, largely<br />

through the intensification <strong>of</strong> poultry production in many parts <strong>of</strong> the world, notably Asia. But<br />

at what cost?<br />

Chicken, once consumed only on special occasions, has become a near-daily staple on dinner<br />

tables around the world as a result <strong>of</strong> animal agriculture practices that have dramatically<br />

changed the landscape <strong>of</strong> farming by confining ever greater numbers <strong>of</strong> animals in ever<br />

decreasing amounts <strong>of</strong> space. In China, the shift from small, backyard poultry rearing toward<br />

industrialized animal agribusiness began to take root in the early 1980s. In just two decades,<br />

Chinese poultry farming has increasingly intensified—and has developed an unintended byproduct:<br />

the prospect <strong>of</strong> an influenza pandemic <strong>of</strong> nightmarish proportions, one that could<br />

devastate humans, poultry, and ecosystems around the world.

Influenza epidemics and pandemics are not new. Yet it wasn’t until 1982 that the late<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Sir Charles Stuart-Harris and I put forward the hypothesis that southern China is an<br />

epicentre for the emergence <strong>of</strong> pandemic influenza <strong>virus</strong>es, the seeds for which had been<br />

germinating for 4,500 years when it was believed the duck was first domesticated in that<br />

region. This established the influenza <strong>virus</strong> gene pool in southern China’s farmyards.<br />

Indeed, molecular and genetic evidence suggests that the chicken is not a natural host for<br />

influenza. Rather, the domestic duck is the silent intestinal carrier <strong>of</strong> avian influenza <strong>virus</strong>es<br />

being raised in close proximity to habitation.<br />

It is the siting <strong>of</strong> large-scale chicken production units, particularly in southern China where<br />

avian influenza <strong>virus</strong>es abound, that is the crux <strong>of</strong> the problem. There, domestic ducks have<br />

been raised on rivers, waterways, and, more recently, with the flooded rice crops cultivated<br />

each year. The importation <strong>of</strong> industrial poultry farming into that same region introduced<br />

millions <strong>of</strong> chickens—highly stressed due to intensive production practices and unsanitary<br />

conditions—into this avian influenza <strong>virus</strong> milieu. The result? An influenza accident waiting to<br />

happen. The H5N1 <strong>virus</strong> signalled its appearance in Hong Kong in 1997, and has since made<br />

its way into dozens <strong>of</strong> countries, infected millions <strong>of</strong> birds, and threatens to trigger a human<br />

catastrophe.<br />

Michael Greger has taken on the formidable task <strong>of</strong> reviewing and synthesizing the many<br />

factors contingent upon chicken production that have brought us to the influenza threat the<br />

world now faces. Drawing upon scientific literature and media reports at large, Dr. Greger<br />

explores the hole we have dug for <strong>our</strong>selves with <strong>our</strong> <strong>own</strong> unsav<strong>our</strong>y practices.<br />

Indeed, while governments and the poultry industry are quick to blame migratory birds as the<br />

s<strong>our</strong>ce <strong>of</strong> the current H5N1 avian influenza <strong>virus</strong>, and to view pandemics as natural<br />

phenomena analogous to, say, sunspots and earthquakes, in reality, human choices and<br />

actions may have had—and may continue to have—a pivotal role in the changing ecology. Now<br />

that anthropogenic behavi<strong>our</strong> has reached unprecedented levels with a concomitant<br />

pronounced zoonotic skew in emerging infectious diseases <strong>of</strong> humans, H5N1 seems like a<br />

cautionary tale <strong>of</strong> how attempts to exploit nature may backfire. The use <strong>of</strong> antibiotics as farm<br />

meal growth promoters leading to antibiotic-resistance in humans or the feeding <strong>of</strong> meat or<br />

bone meal to cattle leading to mad cow disease are cases in point: pr<strong>of</strong>itable in the short term<br />

for animal agriculture, but with the potential for unforeseen and disastrous consequences.<br />

Intensified, industrial poultry production has given us inexpensive chicken, but at what cost to<br />

the animals and at what heightened risk to public health?

We have reached a critical point. We must dramatically change animal farming practices for all<br />

animals.<br />

Michael Greger has achieved much in this volume. He has taken a major step toward balancing<br />

humanity’s account with animals.<br />

Kennedy F. Shortridge<br />

"It was ‘the perfect storm’—a tempest that may happen only<br />

once in a century—a nor’easter created by so rare a<br />

combination <strong>of</strong> factors that it could not possibly have been<br />

worse. "<br />

Sebastian Junger, The Perfect Storm: A True Story <strong>of</strong> Men Against the<br />

Sea]<br />

Most <strong>of</strong> us know the flu—influenza—as a nuisance disease, an annual annoyance to be endured<br />

along with taxes, dentists, and visits with the in-laws. Why worry about influenza when there<br />

are so many more colorfully gruesome <strong>virus</strong>es out there like Ebola? Because influenza is<br />

scientists’ top pick for humanity’s next killer plague. Up to 60 million Americans come d<strong>own</strong><br />

with the flu every year. What if it suddenly turned deadly?<br />

H5N1, the new killer strain <strong>of</strong> avian influenza spreading out <strong>of</strong> Asia, has only killed about a<br />

hundred people as <strong>of</strong> mid-2006. In a world in which millions die <strong>of</strong> diseases like malaria,<br />

tuberculosis, and AIDS, why is there so much concern about bird flu?<br />

Because it’s happened before. Because an influenza pandemic in 1918 became the deadliest<br />

plague in human history, killing up to 100 million people around the world. Because the 1918<br />

flu <strong>virus</strong> was likely a bird flu <strong>virus</strong>. Because that <strong>virus</strong> made more than a quarter <strong>of</strong> all<br />

Americans ill and killed more people in 25 weeks than AIDS has killed in 25 years—yet in<br />

1918, the case mortality rate was less than 5%. H5N1, on the other hand, has <strong>of</strong>ficially killed<br />

half <strong>of</strong> its human victims.<br />

H5N1 took its first human life in Hong Kong in 1997 and has since rampaged west to Russia,<br />

the Middle East, Africa, and Europe. It remains almost exclusively a disease <strong>of</strong> birds, but as the<br />

<strong>virus</strong> has spread, it has continued to mutate. It has developed greater lethality and enhanced<br />

environmental stability, and has begun taking more species under its wing. Influenza <strong>virus</strong>es<br />

don’t typically kill mammals like rodents, but experiments have sh<strong>own</strong> that the latest H5N1<br />

mutants can kill 100% <strong>of</strong> infected mice, practically dissolving their lungs. The scientific world

has never seen anything like it. We’re facing an unprecedented outbreak <strong>of</strong> an unpredictable<br />

<strong>virus</strong>.<br />

Currently in humans, H5N1 is good at killing, but not at spreading. There are three essential<br />

conditions necessary to produce a pandemic. First, a new <strong>virus</strong> must arise from an animal<br />

reservoir, such that humans have no natural immunity to it. Second, the <strong>virus</strong> must evolve to<br />

be capable <strong>of</strong> killing human beings efficiently. Third, the <strong>virus</strong> must succeed in jumping<br />

efficiently from one human to the next. For the <strong>virus</strong>, it’s one small step to man, but one giant<br />

leap to mankind. So far, conditions one and two have been met in spades. Three strikes and<br />

we’re out. If the <strong>virus</strong> triggers a human pandemic, it will not be peasant farmers in Vietnam<br />

dying after handling dead birds or raw poultry—it will be New Yorkers, Parisians, Londoners,<br />

and people in every city, t<strong>own</strong>ship, and village in the world dying after shaking someone’s<br />

hand, touching a doorknob, or simply inhaling in the wrong place at the wrong time.<br />

Mathematical models suggest that it might be possible to snuff out an emerging flu pandemic<br />

at the s<strong>our</strong>ce if caught early enough, but practical considerations may render this an<br />

impossibility. Even if we were able to stamp it out, as long as the same underlying conditions<br />

remain, the <strong>virus</strong> would presumably soon pop back up again, just as it has in the past.<br />

This book explores what those underlying conditions are. The current dialogue surrounding<br />

avian influenza speaks <strong>of</strong> a potential H5N1 pandemic as if it were a natural phenomenon—like<br />

hurricanes, earthquakes, or even a “viral asteroid on a collision c<strong>our</strong>se with humanity” —which<br />

we couldn’t hope to control. The reality, however, is that the next pandemic may be more <strong>of</strong> an<br />

unnatural disaster <strong>of</strong> <strong>our</strong> <strong>own</strong> design.<br />

Since the mid-1970s, previously unkn<strong>own</strong> diseases have surfaced at a pace unheard <strong>of</strong> in the<br />

annals <strong>of</strong> medicine—more than 30 new diseases in 30 years, most <strong>of</strong> them newly discovered<br />

<strong>virus</strong>es. The concept <strong>of</strong> “emerging infectious diseases” used to be a mere curiosity in the field<br />

<strong>of</strong> medicine; now it’s an entire discipline. Where are these diseases coming from?<br />

According to the Smithsonian Institution, there have been three great disease transitions in<br />

human history. The first era <strong>of</strong> human disease began with the acquisition <strong>of</strong> diseases from<br />

domesticated animals, such as tuberculosis, measles, the common cold—and influenza. The<br />

second era came with the Industrial Revolution <strong>of</strong> the 18th and 19th centuries, resulting in an<br />

epidemic <strong>of</strong> the so-called “diseases <strong>of</strong> civilization,” such as cancer, heart disease, stroke, and<br />

diabetes. We are now entering the third age <strong>of</strong> human disease, which started around 30 years<br />

ago—described by medical historians as the age <strong>of</strong> “the emerging plagues.” Never in medical<br />

history have so many new diseases appeared in so short a time. An increasingly broad<br />

consensus <strong>of</strong> infectious disease specialists has concluded that nearly all <strong>of</strong> the ever more

frequent emergent disease episodes in the United States and elsewhere over the past few<br />

years have, in fact, come to us from animals. Their bugs are worse than their bite.<br />

In poultry, bird flu has gone from an exceedingly rare disease to one that crops up every year.<br />

The number <strong>of</strong> serious outbreaks in the first few years <strong>of</strong> the 21st century has already<br />

exceeded the total number <strong>of</strong> outbreaks recorded for the entire 20th century. Bird flu seems to<br />

be undergoing evolution in fast-forward.<br />

The increase in chicken outbreaks has gone hand-in-hand with increased transmission to<br />

humans. A decade ago, human infection with bird flu was essentially unheard <strong>of</strong>. Since H5N1<br />

emerged in 1997, though, chicken <strong>virus</strong>es H9N2 infected children in China in 1999 and 2003,<br />

H7N2 infected residents <strong>of</strong> New York and Virginia in 2002 and 2003, H7N7 infected people in<br />

the Netherlands in 2003, and H7N3 infected poultry workers in Canada in 2004 and a British<br />

farmer in 2006. The bird flu <strong>virus</strong> in the Netherlands outbreak infected more than a thousand<br />

people. What has changed in recent years that could account for this disturbing trend?<br />

All bird flu <strong>virus</strong>es seem to start out harmless to both birds and people. In its natural state, the<br />

influenza <strong>virus</strong> has existed for millions <strong>of</strong> years as an innocuous, intestinal, waterborne<br />

infection <strong>of</strong> aquatic birds such as ducks. If the true home <strong>of</strong> influenza <strong>virus</strong>es is the gut <strong>of</strong> wild<br />

waterfowl, the human lung is a long way from home. How does a waterfowl’s intestinal bug<br />

end up in a human cough? Free-ranging flocks and wild birds have been blamed for the recent<br />

emergence <strong>of</strong> H5N1, but people have kept chickens in their backyards for thousands <strong>of</strong> years,<br />

and birds have been migrating for millions.<br />

In a sense, pandemics aren’t born—they’re made. H5N1 may be a <strong>virus</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>our</strong> <strong>own</strong> <strong>hatching</strong><br />

coming home to roost. According to a spokesperson for the World Health Organization, “The<br />

bottom line is that humans have to think about how they treat their animals, how they farm<br />

them, and how they market them—basically the whole relationship between the animal<br />

kingdom and the human kingdom is coming under stress.” Along with human culpability,<br />

though, comes hope. If changes in human behavior can cause new plagues, changes in human<br />

behavior may prevent them in the future.

Purple Death<br />

Influenza ward in army general hospital, Fort Porter, New York (National Archives, 165-<br />

WW-269-B-4)<br />

What started for millions around the globe as muscle aches and a fever ended days later with<br />

many victims bleeding from their nostrils, ears, and eye sockets.17 Some bled inside their<br />

eyes;18 some bled around them.19 They vomited blood and coughed it up.20 Purple blood<br />

blisters appeared on their skin.21<br />

The Chief <strong>of</strong> the Medical Services, Major Walter V. Brem, described the horror at the time in<br />

the J<strong>our</strong>nal <strong>of</strong> the American Medical Association. He wrote that “<strong>of</strong>ten blood was seen to gush<br />

from a patient’s nose and mouth.”22 In some cases, blood reportedly spurted with such force<br />

as to squirt several feet.23 “When pneumonia appeared,” Major Brem recounted, “the patients<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten spat quantities <strong>of</strong> almost pure blood.”24 They were bleeding into their lungs.<br />

As victims struggled to clear their airways <strong>of</strong> the bloody froth that p<strong>our</strong>ed from their lungs,<br />

their bodies started to turn blue from the lack <strong>of</strong> oxygen, a condition kn<strong>own</strong> as violaceous<br />

heliotrope cyanosis.25 “They’re as blue as huckleberries and spitting blood,” one New York City<br />

physician told a colleague.26 U.S. Army medics noted that this was “not the dusky pallid<br />

blueness that one is accustomed to in failing pneumonia, but rather [a] deep blueness…an<br />

indigo blue color.”27 The hue was so dark that one physician confessed that “it is hard to<br />

distinguish the colored men from the white.”28 “It is only a matter <strong>of</strong> a few h<strong>our</strong>s then until<br />

death comes,” recalled another physician, “and it is simply a struggle for air until they<br />

suffocate.”29 They dr<strong>own</strong>ed in their <strong>own</strong> bloody secretions.30<br />

“It wasn’t always that quick, either,” one historian adds. “And along the way, you had<br />

symptoms like fingers and genitals turning black, and people reporting being able to literally<br />

smell the body decaying before the patient died.”31 “When you’re ill like that you don’t care,”<br />

recalls one flu survivor, now 100 years old. “You don’t care if you live or die.”32<br />

Major Brem described an autopsy: “Frothy, bloody serum p<strong>our</strong>ed from the nose and mouth<br />

when the body was moved, or the head lowered…. Pus streamed from the trachea when the<br />

lungs were removed.”33 Fellow autopsy surgeons discussed what they called a “pathological<br />

nightmare,” with lungs up to six times their normal weight, looking “like melted red currant

jelly.”34 An account published by the National Academies <strong>of</strong> Science describes the lungs taken<br />

from victims as “hideously transformed” from light, buoyant, air-filled structures to dense<br />

sacks <strong>of</strong> bloody fluid.35<br />

There was one autopsy finding physicians reported having never seen before. As people<br />

choked to death, violently coughing up as much as two pints <strong>of</strong> yellow-green pus per day,36<br />

their lungs would sometimes burst internally, forcing air under pressure up underneath their<br />

skin. In the Proceedings <strong>of</strong> the Royal Society <strong>of</strong> Medicine, a British physician noted “one thing<br />

that I have never seen before—namely the occurrence <strong>of</strong> subcutaneous emphysema”—pockets<br />

<strong>of</strong> air accumulating just beneath the skin—“beginning in the neck and spreading sometimes<br />

over the whole body.”37 These pockets <strong>of</strong> air leaking from ruptured lungs made patients crackle<br />

when they rolled onto their sides. In an unaired interview filmed for a PBS American<br />

Experience documentary on the 1918 pandemic, one Navy nurse compared the sound to a<br />

bowl <strong>of</strong> Rice Krispies. The memory <strong>of</strong> that sound—the sound <strong>of</strong> air bubbles moving under<br />

people’s skin—remained so vivid that for the rest <strong>of</strong> her life, she couldn’t be in a room with<br />

anyone eating that popping cereal.38<br />

“[A] dead man has no substance unless one has actually seen<br />

him dead; a hundred million corpses broadcast through<br />

history are no more than a puff <strong>of</strong> smoke in the imagination.”<br />

—Albert Camus, The Plague39<br />

Percent <strong>of</strong> population dying in U.S. cities<br />

In 1918, half the world became infected and 25% <strong>of</strong> all Americans fell ill.40 Unlike the regular<br />

seasonal flu, which tends to kill only the elderly and infirm, the flu <strong>virus</strong> <strong>of</strong> 1918 killed those in<br />

the prime <strong>of</strong> life Public health specialists at the time noted that most influenza victims were<br />

those who “had been in the best <strong>of</strong> physical condition and freest from previous disease.”41

Ninety-nine percent <strong>of</strong> excess deaths were among people under 65 years old.42 Mortality<br />

peaked in the 20- to 34-year-old age group.43 Women under 35 accounted for 70% <strong>of</strong> all<br />

female influenza deaths. In 1918, the average life expectancy in the United States dropped<br />

precipitously to only 37 years.44<br />

Calculations made in the 1920s estimated the global death toll in the vicinity <strong>of</strong> 20 million, a<br />

figure medical historians now consider “almost ludicrously low.”45 The number has been<br />

revised upwards ever since, as more and more records are unearthed. The best estimate<br />

currently stands at 50 to 100 million people dead.46 In some communities, like in Alaska, 50%<br />

<strong>of</strong> the population perished.47<br />

The 1918 influenza pandemic killed more people in a single year than the bubonic plague<br />

(“black death”) in the Middle Ages killed in a century.48 The 1918 <strong>virus</strong> killed more people in<br />

25 weeks than AIDS has killed in 25 years.49 According to one academic reviewer, this “single,<br />

brief epidemic generated more fatalities, more suffering, and more demographic change in the<br />

United States than all the wars <strong>of</strong> the Twentieth Century.”50<br />

In September 1918, according to the <strong>of</strong>ficial published American Medican Association (AMA)<br />

account, the deadliest wave <strong>of</strong> the pandemic spread over the world “like a tidal wave.”51 On<br />

the 11th, Washington <strong>of</strong>ficials disclosed that it had reached U.S. shores.52 September 11, 1918<br />

—the day Babe Ruth led the Boston Red Sox to victory in the World Series—three civilians<br />

dropped dead on the sidewalks <strong>of</strong> neighboring Quincy, Massachusetts.53 It had begun.<br />

When a “typical outbreak” struck Camp Funston in Kansas, the commander, a physician and<br />

former Army Chief <strong>of</strong> Staff, wrote the governor, “There are 1440 minutes in a day. When I tell<br />

you there were 1440 admissions in a day, you realize the strain put on <strong>our</strong> Nursing and Medical<br />

forces….”54 “Stated briefly,” summarized an Army report, “the influenza…occurred as an<br />

explosion.”55<br />

October 1918 became the deadliest month in U.S. history56 and the last week <strong>of</strong> October was<br />

the deadliest week from any cause, at any time. More than 20,000 Americans died in that<br />

week alone.57 Numbers, though, cannot reflect the true horror <strong>of</strong> the time.<br />

“This is a detective story. Here was a mass murderer that was<br />

around 80 years ago and who’s never been brought to justice.<br />

And what we’re trying to do is find the murderer.”<br />

—Jeffery Taubenberger, molecular pathologist and arche-virologist84

Johan Hultin and Mary<br />

Where did this disease come from? Popular explanations at the time included a covert German<br />

biological weapon, the foul atmosphere conjured by the war’s rotting corpses and mustard gas,<br />

or “spiritual malaise due to the sins <strong>of</strong> war and materialism.”85 This was before the influenza<br />

<strong>virus</strong> was discovered, we must remember, and is consistent with other familiar etymological<br />

examples—malaria was contracted from mal and aria (“bad air”) or such quaintly preserved<br />

terms as catching “a cold” and being “under the weather.”86 The committee set up by the<br />

American Public Health Association to investigate the 1918 outbreak could only speak <strong>of</strong> a<br />

“disease <strong>of</strong> extreme communicability.”87 Though the “prevailing disease is generally kn<strong>own</strong> as<br />

influenza,” they couldn’t even be certain that this was the same disease that had been<br />

previously thought <strong>of</strong> as such.88 As the J<strong>our</strong>nal <strong>of</strong> the American Medical Association observed<br />

in October 1918, “The ‘influence’ in influenza is still veiled in mystery.”89<br />

In the decade following 1918, thousands <strong>of</strong> books and papers were written on influenza in a<br />

frenzied attempt to characterize the pathogen. One <strong>of</strong> the most famous medical papers <strong>of</strong> all<br />

time, Alexander Fleming’s “On the Antibacterial Actions <strong>of</strong> Cultures <strong>of</strong> Penicillium,” reported an<br />

attempt to isolate the bug that caused influenza. The full title was “On the Antibacterial Actions<br />

<strong>of</strong> Cultures <strong>of</strong> Penicillium, with Special Reference to Their Use in the Isolation <strong>of</strong> B. Influenzae.”<br />

Fleming was hoping he could use penicillin to kill <strong>of</strong>f all the contaminant bystander bacteria on<br />

the culture plate so he could isolate the bug that caused influenza. The possibility <strong>of</strong> treating<br />

humans with penicillin was mentioned only in passing at the end <strong>of</strong> the paper.90<br />

The cause <strong>of</strong> human influenza was not found until 1933, when a British research team finally<br />

isolated and identified the viral culprit.91 What they discovered, though, was a <strong>virus</strong> that<br />

caused the typical seasonal flu. Scientists still didn’t understand where the flu <strong>virus</strong> <strong>of</strong> 1918<br />

came from or why it was so deadly. It would be more than a half-century before molecular<br />

biological techniques would be developed and refined enough to begin to answer these<br />

questions; but by then where would researchers find 1918 tissue samples to study the <strong>virus</strong>?

The U.S. Armed Forces Institute <strong>of</strong> Pathology originated almost 150 years ago. It came into<br />

being during the Civil War, created by an executive order from Abraham Lincoln to the Army<br />

Surgeon General to study diseases in the battlefield.92 It houses literally tens <strong>of</strong> millions <strong>of</strong><br />

pieces <strong>of</strong> preserved human tissue, the largest collection <strong>of</strong> its kind in the world.93 This is where<br />

civilian pathologist Jeffery Taubenberger first went to look for tissue samples in the mid ’90s. If<br />

he could find enough fragments <strong>of</strong> the <strong>virus</strong> he felt he might be able to decipher the genetic<br />

code and perhaps even resurrect the 1918 <strong>virus</strong> for study, the viral equivalent <strong>of</strong> bringing<br />

dinosaurs back to life in Jurassic Park.94<br />

He found remnants <strong>of</strong> two soldiers who succumbed to the 1918 flu on the same day in<br />

September—a 21-year-old private who died in South Carolina and a 30-year-old private who<br />

died in upstate New York. Tiny cubes <strong>of</strong> lung tissue preserved in wax were all that remained.<br />

Taubenberger’s team shaved <strong>of</strong>f microscopic sections and started hunting for the <strong>virus</strong> using<br />

the latest advances in modern molecular biology that he himself had helped devise. They<br />

found the <strong>virus</strong>, but only in tiny bits and pieces.95<br />

The influenza <strong>virus</strong> has eight gene segments, a genetic code less than 14,000 letters long (the<br />

human genome, in contrast, has several billion). The longest stands <strong>of</strong> RNA (the <strong>virus</strong>’s genetic<br />

material) that Taubenberger could find in the soldiers’ tissue were only about 130 letters long.<br />

He needed more tissue.96<br />

The 1918 pandemic littered the Earth with millions <strong>of</strong> corpses. How hard could it be to find<br />

more samples? Unfortunately, refrigeration was essentially nonexistent in 1918, and common<br />

tissue preservatives like formaldehyde tended to destroy any trace <strong>of</strong> RNA.97 He needed tissue<br />

samples frozen in time. Expeditions were sent north, searching for corpses frozen under the<br />

Arctic ice.<br />

Scientists needed to find corpses buried below the permafrost layer, the permanently frozen<br />

layer <strong>of</strong> subsoil beneath the topsoil, which itself may thaw in the summer.98 Many teams over<br />

the years tried and failed. U.S. Army researchers excavated a mass grave near Nome, Alaska,<br />

for example, only to find skeletons.99 “Lots <strong>of</strong> those people are buried in permafrost,”<br />

explained Pr<strong>of</strong>essor John Oxford, co-author <strong>of</strong> two standard virology texts, “but many <strong>of</strong> them<br />

were eaten by the huskies after they died. Or,” he added, “before they died.”100<br />

On a remote Norwegian Island, Kirsty Duncan, a medical geographer from Canada, led the<br />

highest pr<strong>of</strong>ile expedition in 1998, dragging 12 tons <strong>of</strong> equipment and a blue-ribbon academic<br />

team to the gravesite <strong>of</strong> seven coal miners who had succumbed to the 1918 flu.101 Years <strong>of</strong><br />

planning and research combined with surveys using ground-penetrating radar had led the<br />

team to believe that the bodies <strong>of</strong> the seven miners had been buried deep in the eternal

permafrost.102 Hunched over the unearthed c<strong>of</strong>fins in biosecure space suits, the team soon<br />

realized their search was in vain.103 The miners’ naked bodies, wrapped only in newspaper, lay<br />

in shallow graves above the permafrost. Subjected to thawing and refreezing over the<br />

decades, the tissue was useless.104<br />

Nearly 50 years earlier, scientists from the University <strong>of</strong> Iowa, including a graduate student<br />

recently arrived from Sweden named Johan Hultin, had made a similar trek to Alaska with<br />

similarly disappointing results.105 In the fall <strong>of</strong> 1918, the postal carrier delivered the mail—and<br />

the flu—via dogsled to a missionary station in Brevig, Alaska.106 Within five days, 72 <strong>of</strong> the 80<br />

or so missionaries lay dead.107 With help from a nearby Army base, the remaining eight buried<br />

the dead in a mass grave.108 Governor Thomas A. Riggs spent Alaska into bankruptcy caring<br />

for the orphaned children at Brevig and across the state. “I could not stand by and see <strong>our</strong><br />

people dying like flies.”109<br />

Learning <strong>of</strong> Taubenberger’s need for better tissue samples, Johan Hultin returned to Brevig a<br />

few weeks before his 73rd birthday.110 Hultin has been described as “the Indiana Jones <strong>of</strong> the<br />

scientific set.”111 In contrast to Duncan’s team, which spent six months just searching for the<br />

most experienced gravediggers, Hultin struck out alone.112 Hultin was “there with a pickaxe,”<br />

one colleague relates. “He dug a pit though solid ice in three days. This guy is unbelievable. It<br />

was just fantastic.”113<br />

Among the many skeletons lay a young woman whose obesity insulated her internal organs.<br />

“She was lying on her back, and on her left and right were skeletons, yet she was amazingly<br />

well preserved. I sat on an upside-d<strong>own</strong> pail, amid the icy pond water and the muck and<br />

fragrance <strong>of</strong> the grave,” Hultin told an interviewer, “and I thought, ‘Here’s where the <strong>virus</strong> will<br />

be found and shed light on the flu <strong>of</strong> 1918.’”114 He named her Lucy. A few days later,<br />

Taubenberger received a plain br<strong>own</strong> box in the mail containing both <strong>of</strong> Lucy’s lungs.115 As<br />

Hultin had predicted, hidden inside was the key to unlock the mystery.<br />

Many had assumed that the 1918 <strong>virus</strong> came from pigs. Although the human influenza <strong>virus</strong><br />

wasn’t even discovered until 1933, as early as 1919 an inspector with the U.S. Bureau <strong>of</strong><br />

Animal Industry was publishing research that suggested a role for farm animals in the<br />

pandemic. Inspector J.S. Koen <strong>of</strong> Fort Dodge, Iowa wrote:<br />

The similarity <strong>of</strong> the epidemic among people and the epidemic among pigs was so close, the<br />

reports so frequent, that an outbreak in the family would be followed immediately by an<br />

outbreak among the hogs, and vice versa, as to present a most striking coincidence if not<br />

suggesting a close relation between the two conditions. It looked like “flu,” and until proven it<br />

was not “flu,” I shall stand by that diagnosis.116<br />

According to the editor <strong>of</strong> the medical j<strong>our</strong>nal Virology, Koen’s views were decidedly unpopular,<br />

especially among pig farmers who feared that customers “would be put <strong>of</strong>f from eating pork if

such an association was made.”117 It was never clear, though, whether the pigs were the<br />

culprits or the victims. Did we infect the pigs or did they infect us?<br />

With the entire genome <strong>of</strong> the 1918 <strong>virus</strong> in hand thanks to Hultin’s expedition, Taubenberger<br />

was finally able to definitively answer the Holy Grail question posed by virologists the world<br />

over throughout the century: Where did the 1918 <strong>virus</strong> come from? The answer, published in<br />

October 2005,118 is that humanity’s greatest killer appeared to come from avian influenza—<br />

bird flu.119<br />

Evidence now suggests that all pandemic influenza <strong>virus</strong>es—in fact all human and mammalian<br />

flu <strong>virus</strong>es in general—owe their origins to avian influenza.120 Back in 1918, schoolchildren<br />

jumped rope to a morbid little rhyme:<br />

I had a little bird,<br />

Its name was Enza.<br />

I opened the window,<br />

And in-flu-enza.121<br />

The children <strong>of</strong> 1918 may have been more prescient than anyone dared imagine.<br />

Resurrection<br />

Dr. Taubenberger attempts to map out the 1918 <strong>virus</strong><br />

Sequencing the 1918 <strong>virus</strong> is one thing; bringing it back to life is something else. Using a new<br />

technique called “reverse genetics,” Taubenberger teamed up with groups at Mount Sinai and<br />

the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and set out to raise it from the<br />

dead.122 Using the genetic blueprint provided by Lucy’s frozen lungs, they painstakingly<br />

recreated each <strong>of</strong> the genes <strong>of</strong> the <strong>virus</strong>, one letter at a time. Upon completion, they stitched<br />

each gene into a loop <strong>of</strong> genetically manipulated bacterial DNA and introduced the DNA loops<br />

into mammalian cells.123 The 1918 <strong>virus</strong> was reborn.<br />

Ten vials <strong>of</strong> <strong>virus</strong> were created, each containing 10 million infectious <strong>virus</strong> particles.124 First<br />

they tried infecting mice. All were dead in a matter <strong>of</strong> days. “The resurrected <strong>virus</strong> apparently<br />

hasn’t lost any <strong>of</strong> its kick,” Taubenberger noted. Compared to a typical non-lethal human flu

strain, the 1918 <strong>virus</strong> generated 39,000 times more <strong>virus</strong> particles in the animals’ lungs. “I<br />

didn’t expect it to be as lethal as it was,” one <strong>of</strong> the co-authors <strong>of</strong> the study remarked.125<br />

The experiment was hailed as a “huge breakthrough,”126 a “t<strong>our</strong> de force.”127 “I can’t think <strong>of</strong><br />

anything bigger that’s happened in virology for many years,” cheered one leading scientist.128<br />

Not knowing the true identity <strong>of</strong> the 1918 flu had been “like a dark angel hovering over us.”129<br />

Critics within the scientific community, however, wondered whether the box Taubenberger had<br />

received from Hultin might just as well have been addressed to Pandora. One scientist<br />

compared the research to “looking for a gas leak with a lighted match.”130 “They have<br />

constructed a <strong>virus</strong>,” one biosecurity specialist asserted, “that is perhaps the most effective<br />

bioweapon kn<strong>own</strong>.”131 “This would be extremely dangerous should it escape, and there is a<br />

long history <strong>of</strong> things escaping,” warned a member <strong>of</strong> the Federation <strong>of</strong> American Scientists’<br />

Working Group on Biological Weapons.132 Taubenberger and his collaborators were criticized<br />

for using only an enhanced Biosafety Level 3 lab to resurrect the <strong>virus</strong> rather than the strictest<br />

height <strong>of</strong> security, Level 4. Critics cite three recent examples where deadly <strong>virus</strong>es had<br />

escaped accidentally from high-security labs.133<br />

In 2004, for example, a strain <strong>of</strong> influenza that killed a million people in 1957 was accidentally<br />

sent to thousands <strong>of</strong> labs around the globe within a routine testing kit. Upon learning <strong>of</strong> the<br />

error, the World Health Organization called for the immediate destruction <strong>of</strong> all the kits.<br />

Miraculously, none <strong>of</strong> the <strong>virus</strong> managed to escape any <strong>of</strong> the labs. Klaus Stöhr, head <strong>of</strong> the<br />

World Health Organization’s global influenza program, admitted that it was fair to say that the<br />

laboratory accident with the unlabeled <strong>virus</strong> could have started a flu pandemic. “If many badluck<br />

things had come together, it could have really caused a global health emergency.”134 “We<br />

can’t have this happen,” remarked Michael Osterholm, the director <strong>of</strong> the Center for Infectious<br />

Disease Research and Policy at the University <strong>of</strong> Minnesota. “Who needs terrorists or Mother<br />

Nature, when through <strong>our</strong> <strong>own</strong> stupidity, we do things like this?”135<br />

Not only was the 1918 <strong>virus</strong> revived, risking an accidental release from the lab, but in the<br />

interest <strong>of</strong> promoting further scientific exploration, Taubenberger’s group openly published the<br />

entire viral genome on the internet, letter for letter. This was intended to allow other scientists<br />

the opportunity to try to decipher the <strong>virus</strong>’s darkest secrets. The public release <strong>of</strong> the genetic<br />

code, however, meant that rogue nations or bioterrorist groups had been afforded the same<br />

access. “In an age <strong>of</strong> terrorism, in a time when a lot <strong>of</strong> folks have malicious intent toward us, I<br />

am very nervous about the publication <strong>of</strong> accurate [gene] sequences for these pathogens and<br />

the techniques for making them,” said a bioethicist at the University <strong>of</strong> Pennsylvania.136 “Once<br />

the genetic sequence is publicly available,” explained a virologist at the National Institute for<br />

Biological Standards and Control, “there’s a theoretical risk that any molecular biologist with<br />

sufficient knowledge could recreate this <strong>virus</strong>.”137

Even if the 1918 <strong>virus</strong> were to escape, there might be a graver threat waiting in the wings. As<br />

devastating as the 1918 pandemic was, on average the mortality rate was less than 5%.138<br />

The H5N1 strain <strong>of</strong> bird flu <strong>virus</strong> now spreading like a plague across the world currently kills<br />

about 50% <strong>of</strong> its kn<strong>own</strong> human victims, on par with some strains <strong>of</strong> Ebola,139 making it<br />

potentially ten times as deadly as the worst plague in human history.140,141 “The picture <strong>of</strong><br />

what the [H5N1] <strong>virus</strong> can do to humans,” said the former chief <strong>of</strong> infectious disease at<br />

Children’s Hospital in Boston, “is pretty gruesome in terms <strong>of</strong> its mortality.”142<br />

Leading public health authorities, from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to<br />

the World Health Organization, fear that this bird flu <strong>virus</strong> is but mutations away from<br />

spreading efficiently though the human population, triggering the next pandemic. “The lethal<br />

capacity <strong>of</strong> this <strong>virus</strong> is very, very high; so it’s a deadly <strong>virus</strong> that humans have not been<br />

exposed to before. That’s a very bad combination,” says Irwin Redlener, director <strong>of</strong> the<br />

National Center for Disaster Preparedness at Columbia University.143 Scientists have<br />

speculated worst-case scenarios in which H5N1 could end up killing a billion144 or more145<br />

people around the globe. “The only thing I can think <strong>of</strong> that could take a larger human death<br />

toll would be thermonuclear war,” said Council on Foreign Relations senior fellow Laurie<br />

Garrett.146 H5N1 could potentially become a <strong>virus</strong> as ferocious as Ebola and as contagious as<br />

the common cold.<br />

Tiny Terrorists<br />

Ebola <strong>virus</strong><br />

If, as Nobel laureate Peter Medawar has said, a <strong>virus</strong> “is a piece <strong>of</strong> bad news wrapped in a<br />

protein,”147 the world may have all the bad news it can handle with the emergence <strong>of</strong> the<br />

H5N1 <strong>virus</strong>. For more than a century, scientists have marveled at how a <strong>virus</strong>, one <strong>of</strong> the<br />

simplest, most marginal life forms, could present such a threat. “It’s on the edge <strong>of</strong> life,”<br />

explains a former director <strong>of</strong> the CDC’s viral diseases division, “between living organism and<br />

pure chemical—but it seems alive to me.”148<br />

For a <strong>virus</strong>, less is more. Viruses are measured in millionths <strong>of</strong> a millimeter.149 As one writer<br />

described them, “Like tiny terrorists, <strong>virus</strong>es travel light, switch identity easily and pursue their<br />

goals with deadly determination.”150

Viruses are simply pieces <strong>of</strong> genetic material, DNA or RNA, enclosed in a protective coat. As<br />

such, they face three challenges. First, they have genes, but no way to reproduce, so they<br />

must take over a living cell and parasitically hijack its molecular machinery for reproduction<br />

and energy production. The second problem <strong>virus</strong>es face is how to spread from one host to<br />

another. If the <strong>virus</strong> is too passive, it may not spread during the host’s natural lifespan and<br />

thus will be buried with its host. The <strong>virus</strong> must not be too virulent, though. If a <strong>virus</strong> comes<br />

on too strong, it may kill its host before it has a chance to infect others, in which case the<br />

<strong>virus</strong> will also perish. Finally, all <strong>virus</strong>es need to be able to evade the host’s defenses. Different<br />

<strong>virus</strong>es have found different strategies to accomplish each <strong>of</strong> these tasks.151<br />

“A hen is only an egg's way <strong>of</strong> making another egg.”<br />

—Samuel Butler<br />

Toxoplasma life cycle<br />

A <strong>virus</strong> is a set <strong>of</strong> instructions to make the proteins that allow it to spread and reproduce.<br />

Viruses have no legs, no wings, no way to move around. They even lack the whip-like<br />

appendages that many bacteria use for locomotion. So <strong>virus</strong>es must trick the host into doing<br />

the spreading for them. One sees similar situations throughout nature. Plants can’t walk from<br />

place to place, so many have evolved flowers with sweet nectar to attract bees who spread the<br />

plants’ reproductive pollen for them. Cockleburs have barbs to hitch rides on furry animals;<br />

berries developed sweetness so that birds would excrete seeds miles away. Viruses represent<br />

this evolutionary instinct boiled d<strong>own</strong> to its essence.<br />

The rabies <strong>virus</strong>, for example, is programmed to infect parts <strong>of</strong> the animal brain that induce<br />

uncontrollable rage, while at the same time replicating in the salivary glands to spread itself

est through the provoked frenzy <strong>of</strong> biting.152 Toxoplasma, though not a <strong>virus</strong>, uses a similar<br />

mechanism to spread. The disease infects the intestines <strong>of</strong> cats, is excreted in the feces, and is<br />

then picked up by an intermediate host—like a rat or mouse—who is eaten by another cat to<br />

complete the cycle. To facilitate its spread, the toxoplasma parasite worms its way into the<br />

rodent’s brain and actually alters the rodent’s behavior, amazingly turning the animal’s natural<br />

anti-predator aversion to cats into an imprudent attraction.153<br />

Diseases like cholera and rota<strong>virus</strong> spread through feces, so, not surprisingly, they cause<br />

explosive diarrhea. Ebola is spread by blood, so it makes you bleed. Blood-borne travel is not<br />

very efficient, though. Neither is dog or even mosquito saliva, at least not for a <strong>virus</strong> that sets<br />

its sights high. Viruses that “figure out” how to travel the respiratory route, or the venereal<br />

route, have the potential to infect millions. Of the two, though, it’s easier to practice safe sex<br />

than it is to stop breathing.<br />

Something in the Air<br />

Influenza <strong>virus</strong><br />

Viruses like influenza have only about a week to proliferate before the host kills them or, in<br />

extreme cases, they kill the host. During this contagious period there may be a natural<br />

selection toward <strong>virus</strong>es <strong>of</strong> greater virulence to overwhelm host defenses. Our bodies fight<br />

back with a triple firewall strategy to fend <strong>of</strong>f viral attackers. The first is <strong>our</strong> set <strong>of</strong> barrier<br />

defenses.<br />

The outermost part <strong>of</strong> <strong>our</strong> skin is composed <strong>of</strong> 15 or more layers <strong>of</strong> dead cells bonded together<br />

with a fatty cement.154 A new layer forms every day as dead cells are sloughed <strong>of</strong>f, so about<br />

every two weeks, the entire layer is completely replaced.155 Since <strong>virus</strong>es can only reproduce<br />

in live functional cells and the top layers <strong>of</strong> skin are dead, <strong>our</strong> intact skin represents a<br />

significant barrier to any viral infection.<br />

But the respiratory tract has no such protection. Not only is <strong>our</strong> respiratory tract lined with<br />

living tissue, it represents <strong>our</strong> primary point <strong>of</strong> contact with the external world. We only have<br />

about two square yards <strong>of</strong> skin, but the surface area within the convoluted inner passageways

<strong>of</strong> <strong>our</strong> lungs exceeds that <strong>of</strong> a tennis c<strong>our</strong>t.156 And every day we inhale more than 5,000<br />

gallons <strong>of</strong> air.157 For a <strong>virus</strong>, especially one not adapted to survive stomach acid, the lungs are<br />

the easy way in.<br />

Our bodies are well aware <strong>of</strong> these vulnerabilities. It’s not enough for a <strong>virus</strong> to be inhaled; it<br />

must be able to physically infect a live cell. This is where mucus comes in. Our airways are<br />

covered with a layer <strong>of</strong> mucus that keeps <strong>virus</strong>es at arm’s length from <strong>our</strong> cells. Many <strong>of</strong> the<br />

cells themselves are equipped with tiny sweeping hairs that brush the contaminated mucus up<br />

to the throat to be coughed up or swallowed into the killing acid <strong>of</strong> the stomach. One <strong>of</strong> the<br />

reasons smokers are especially susceptible to respiratory infections in general is that the toxins<br />

in cigarette smoke paralyze and destroy these fragile little sweeper cells.158<br />

Our respiratory tract produces a healthy half-cup <strong>of</strong> snot every day,159 but can significantly<br />

ramp up production in the event <strong>of</strong> infection. Influenza <strong>virus</strong>es belong to the “orthomyxo<strong>virus</strong>”<br />

family, from the Greek orthos- myxa-, meaning “straight mucus.” The influenza <strong>virus</strong> found a<br />

way to cut through this barrier defense.<br />

Unlike most <strong>virus</strong>es, which have a consistent shape, influenza <strong>virus</strong>es may exist as round balls,<br />

spaghetti-like filaments, or any shape in between.160 One characteristic they all share, though,<br />

is the presence <strong>of</strong> hundreds <strong>of</strong> spikes protruding from all over the surface <strong>of</strong> the <strong>virus</strong>, much<br />

like pins in a pincushion.161 There are two types <strong>of</strong> spikes. One is a triangular, rod-shaped<br />

protein called hemagglutinin.162 The other is a square, mushroom-shaped enzyme called<br />

neuraminidase.<br />

There have been multiple varieties <strong>of</strong> both enzymes described, so far 16 hemagglutinin (H1 to<br />

H16) and 9 neuraminidase (N1 to N9). Influenza strains are identified by which two surface<br />

enzymes they display. The strain identified as “H5N1” denotes that the <strong>virus</strong> is studded with<br />

the fifth hemagglutinin in the WHO-naming scheme, along with spikes <strong>of</strong> the first<br />

neuraminidase.163<br />

There is a reason the <strong>virus</strong> has neuraminidase jutting from its surface. Described by virologists<br />

as having a shape resembling a “strikingly long-stalked mushroom,”164 this enzyme has the<br />

ability to slash through mucus like a machete, dissolving through the mucus layer to attack the<br />

respiratory cells underneath.165 Then the hemagglutinin spikes take over.<br />

Hemagglutinin is the key the <strong>virus</strong> uses to get inside <strong>our</strong> cells. The external membrane that<br />

wraps each cell is studded with glycoproteins—complexes <strong>of</strong> sugars and proteins—that are<br />

used for a variety <strong>of</strong> functions, including cell-to-cell communication. The cells <strong>of</strong> <strong>our</strong> body are<br />

effectively sugar-coated. The viral hemagglutinin binds to one such sugar called sialic acid<br />

(from the Greek sialos for “saliva”) like Velcro hooks on a loop. In fact, that’s how

hemagglutinin got its name. If you mix the influenza <strong>virus</strong> with a sample <strong>of</strong> blood, the<br />

hundreds <strong>of</strong> surface hemagglutinin spikes on each viral particle form crosslinks between<br />

multiple sialic acid-covered red blood cells, effectively clumping them together. It agglutinates<br />

(glutinare or “to glue”) blood (heme-).166<br />

The docking maneuver prompts the cell to engulf the <strong>virus</strong>. Like some Saturday Night Live<br />

“landshark” skit, the <strong>virus</strong> fools the cell into letting it inside. Once inside it takes over, turning<br />

the cell into a <strong>virus</strong>-producing factory. The conquest starts with the <strong>virus</strong> chopping up <strong>our</strong> <strong>own</strong><br />

cell’s DNA and retooling the cell to switch over production to make more <strong>virus</strong> with a singlemindedness<br />

that eventually leads to the cell’s death through the neglect <strong>of</strong> its <strong>own</strong> needs.167<br />

Why has the <strong>virus</strong> evolved to kill the cell, to burn d<strong>own</strong> its <strong>own</strong> factory? Why bite the hand that<br />

feeds it? Why not just hijack half <strong>of</strong> the cell’s protein-making capacity and keep the cell alive to<br />

make more <strong>virus</strong>? After all, the more cells that end up dying, the quicker the immune system<br />

is tipped <strong>of</strong>f to the <strong>virus</strong>’s presence. The <strong>virus</strong> kills because killing is how the <strong>virus</strong> gets around.<br />

Influenza transmission is legendary. The dying cells in the respiratory tract trigger an<br />

inflammatory response, which triggers the cough reflex. The <strong>virus</strong> uses the body’s <strong>own</strong><br />

defenses to infect others. Each cough releases billions <strong>of</strong> newly made <strong>virus</strong>es from the body at<br />

an ejection velocity exceeding 75 miles an h<strong>our</strong>.168 Sneezes can exceed 100 miles per h<strong>our</strong>169<br />

and hurl germs as far away as 40 feet.170 Furthermore, the viral neuraminidase’s ability to<br />

liquefy mucus promotes the formation <strong>of</strong> tiny aerosolized droplets,171 which are so light they<br />

can hang in the air for minutes before settling to the ground.172 Each cough produces about<br />

40,000 such droplets,173 and each microdroplet can contain millions <strong>of</strong> <strong>virus</strong>es.174 One can see<br />

how easily a <strong>virus</strong> like this could spread around the globe.<br />

In terms <strong>of</strong> viral strategy, another advantage <strong>of</strong> the respiratory tract is its tennis c<strong>our</strong>t–sized<br />

surface area which allows the <strong>virus</strong> to go on killing cell after cell, thereby making massive<br />

quantities <strong>of</strong> <strong>virus</strong> without killing the host too quickly. The <strong>virus</strong> essentially turns <strong>our</strong> lungs into<br />

flu <strong>virus</strong> factories. In contrast, <strong>virus</strong>es that attack other vital organs like the liver can only<br />

multiply so fast without taking the host d<strong>own</strong> with them.175<br />

Unlike some other <strong>virus</strong>es, like the herpes <strong>virus</strong>, which go out <strong>of</strong> their way not to kill cells so as<br />

not to incur <strong>our</strong> immune system’s wrath, the influenza <strong>virus</strong> has no such option. It must kill to<br />

live, kill to spread. It must make us cough, and the more violently the better.

Makings <strong>of</strong> a Killer<br />

NS1 protein binding to RNA<br />

The first line <strong>of</strong> <strong>our</strong> triple firewall against infection is <strong>our</strong> barrier defense. Once this wall is<br />

breached, we have to rely on an array <strong>of</strong> nonspecific defenses kn<strong>own</strong> as the “innate” arm <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>our</strong> immune system. These are typified by Pacman-like roving cells called macrophages<br />

(literally from the Greek for “big eaters”), which roam the body chewing up any pathogens<br />

they can catch. In this way, any <strong>virus</strong>es caught outside <strong>our</strong> cells can get gobbled up. Once<br />

<strong>virus</strong>es invade <strong>our</strong> cells, however, they are effectively hidden from <strong>our</strong> roaming defenses. This<br />

is where <strong>our</strong> interferon system comes in.<br />

Interferon is one <strong>of</strong> the body’s many cytokines, inflammatory messenger proteins produced by<br />

cells under attack that can warn neighboring cells <strong>of</strong> an impending viral assault.176 Interferon<br />

acts as an early warning system, communicating the viral threat and activating in the cell a<br />

complex self-destruct mechanism should nearby cells find themselves infected. Interferon<br />

instructs cells to kill themselves at the first sign <strong>of</strong> infection and take the <strong>virus</strong> d<strong>own</strong> with<br />

them. They should take one for the team and jump on a grenade to protect the rest <strong>of</strong> the<br />

body. This order is not taken lightly; false alarms could be devastating to the body. Interferon<br />

pulls the pin, but the cell doesn’t drop the grenade unless it’s absolutely sure it’s infected.<br />

This is how it works. When scientists sit d<strong>own</strong> and try to create a new antibiotic (anti- bios,<br />

“against life”), they must find some difference to exploit between <strong>our</strong> living cells and the<br />

pathogen in question. It’s like trying to formulate chemotherapy to kill the cancer cells but<br />

leave normal cells alone. There is no doubt that bleach and formaldehyde are supremely<br />

effective at destroying bacteria and <strong>virus</strong>es, but the reason we don’t chug them at the first<br />

sign <strong>of</strong> a cold is they are toxic to us as well.<br />

Most antibiotics, like penicillin, target the bacterial cell wall. Since animal cells don’t have cell<br />

walls, these drugs can wipe out bacteria and leave us still standing. Pathogenic fungi don’t<br />

have bacterial cell walls, but they do have unique fatty compounds in their cell membranes

that <strong>our</strong> antifungals can target and destroy. Viruses have neither cell walls nor fungal<br />

compounds, and therefore these antibiotics and antifungals don’t work against <strong>virus</strong>es. There’s<br />

not much to a <strong>virus</strong> to single out and attack. There’s the viral RNA or DNA, <strong>of</strong> c<strong>our</strong>se, but<br />

that’s the same genetic material as in <strong>our</strong> cells.<br />

Human DNA is double-stranded (the famous spiral “double helix”), whereas human RNA is<br />

predominantly single-stranded.177 To copy its RNA genome to repackage into new <strong>virus</strong>es, the<br />

influenza <strong>virus</strong> carries along an enzyme that travels the length <strong>of</strong> the viral RNA to make a<br />

duplicate strand. For a split second, there are two intertwined RNA strands. That’s the body’s<br />

signal that something is awry. When a <strong>virus</strong> is detected, interferon tells neighboring cells to<br />

start making a suicide enzyme called PKR that shuts d<strong>own</strong> all protein synthesis in the cell,<br />

stopping the <strong>virus</strong>, but also killing the cell in the process.178 To start this deadly cascade, PKR<br />

must first be activated. PKR is activated by double-stranded RNA.179<br />

What interferon does is prime the cells <strong>of</strong> the body for viral attack. Cells preemptively build up<br />

PKR to be ready for the <strong>virus</strong>. An ever-vigilant sentry, PKR continuously scans cells for the<br />

presence <strong>of</strong> double-stranded RNA. As soon as the PKR detects that characteristic signal <strong>of</strong> viral<br />

invasion, the PKR kills the cell and hopes to take d<strong>own</strong> the <strong>virus</strong> with it. Our cells die, but they<br />

go d<strong>own</strong> fighting. This defense strategy is so effective in blunting a viral onslaught that biotech<br />

companies are now trying to genetically engineer double-stranded RNA to be taken in pill form<br />

during a viral attack in hopes <strong>of</strong> accelerating this process.180<br />

Cytokines like interferon have beneficial systemic actions as well. Interferon release leads to<br />

many <strong>of</strong> the other symptoms we associate with the flu, such as high fever, fatigue, and muscle<br />

aches.181 The fever is valuable since <strong>virus</strong>es like influenza tend to replicate poorly at high<br />

temperatures. Some like it hot, but not the influenza <strong>virus</strong>. The achy malaise enc<strong>our</strong>ages us to<br />

rest so <strong>our</strong> bodies can shift energies to mounting a more effective immune response.182 On a<br />

population level, these intentional side effects may also limit the spread <strong>of</strong> the <strong>virus</strong> by limiting<br />

the spread <strong>of</strong> the host, who may feel too lousy to go out and socialize. Cytokine side effects<br />

are <strong>our</strong> body’s way <strong>of</strong> telling us to call in sick.<br />

Normally when you pretreat cells in the lab with powerful antivirals like interferon, the cells are<br />

forewarned and forearmed, and viral replication is effectively blocked.183 Not so with H5N1,<br />

the deadly bird flu <strong>virus</strong> spreading out <strong>of</strong> Asia. Somehow this new influenza threat is<br />

counteracting the body’s antiviral defenses, but how?<br />

Viruses have evolved a blinding array <strong>of</strong> ways to counter <strong>our</strong> body’s finest attempts at control.<br />

The smallpox <strong>virus</strong>, for example, actually produces what are called “decoy receptors” to bind<br />

up the body’s cytokines so that less <strong>of</strong> them make it out to other cells.184 “I am in awe <strong>of</strong><br />

these minute creatures,” declared a Stanford microbiologist. “They know more about the

iology <strong>of</strong> the human cell than most cell biologists. They know how to tweak it and how to<br />

exploit it.”185<br />

How does H5N1 block interferon’s interference? After all, the <strong>virus</strong> can’t stop replicating its<br />

RNA. The H5N1 <strong>virus</strong> carries a trick up its sleeve called NS1 (for “Non-Structural” protein). If<br />

interferon is the body’s antiviral warhead, then the NS1 protein is the H5N1’s antiballistic<br />

missile.186 NS1 itself binds to the <strong>virus</strong>’s <strong>own</strong> double-stranded RNA, effectively hiding it from<br />

the cell’s PKR cyanide pill, preventing activation <strong>of</strong> the self-destruct sequence. Interferon can<br />

pull the pin, but the cell can’t let go <strong>of</strong> the grenade. NS1 essentially foils the body’s attempt by<br />

covering up the <strong>virus</strong>’s tracks. Influenza <strong>virus</strong>es have been called a “showcase for viral<br />

cleverness.”187<br />

All influenza <strong>virus</strong>es have NS1 proteins, but H5N1 carries a mutated NS1 with enhanced<br />

interferon-blocking abilities. The H5N1’s viral countermove isn’t perfect. The <strong>virus</strong> just needs<br />

to buy itself enough time to spew out new <strong>virus</strong>. Then it doesn’t care if the cell goes d<strong>own</strong> in<br />

flames—in fact, the <strong>virus</strong> prefers it, because the cell’s death may trigger more coughing. “This<br />

is a really nasty trick that this <strong>virus</strong> has learnt: to bypass all the innate mechanisms that cells<br />

have for shutting d<strong>own</strong> the <strong>virus</strong>,” laments the chief researcher who first unearthed H5N1’s<br />

deadly secret. “It is the first time this mechanism has sh<strong>own</strong> up and we wonder if it was not a<br />

similar mechanism that made the 1918 influenza <strong>virus</strong> so enormously pathogenic.”188<br />

Now that researchers actually had the 1918 <strong>virus</strong> in hand, it was one <strong>of</strong> the first things they<br />

tested in hopes <strong>of</strong> understanding why the apocalyptic pandemic was so extraordinarily deadly.<br />

They tested the <strong>virus</strong> in a tissue culture <strong>of</strong> human lung cells, and, indeed, the 1918 <strong>virus</strong> was<br />

using the same NS1 trick to undermine the interferon system.189 As the University <strong>of</strong><br />

Minnesota’s Osterholm told Oprah Winfrey, H5N1 is a “kissing cousin <strong>of</strong> the 1918 <strong>virus</strong>.”190<br />

H5N1 may come to mean 1918 all over again.<br />

“But what gave this pestilence particularly severe force was<br />

that whenever the diseased mixed with healthy people, like a<br />

fire through dry grass or oil, it would run upon the healthy.”<br />

—Boccaccio’s description <strong>of</strong> the plague in Florence in his classic<br />

Decameron, published in 1350191

1918 deaths peaked among young adults<br />

H5N1 shares another ominous trait with the <strong>virus</strong> <strong>of</strong> 1918: They both have a taste for the<br />

young. One <strong>of</strong> the greatest mysteries <strong>of</strong> the 1918 pandemic was, in the words <strong>of</strong> then Acting<br />

Surgeon General <strong>of</strong> the Army, why “the infection, like war, kills the young vigorous robust<br />

adults.”192 As the American Public Health Association put it rather crudely at the time: “The<br />

major portion <strong>of</strong> this mortality occurred between the ages <strong>of</strong> 20 and 40, when human life is <strong>of</strong><br />

the highest economic importance.”193<br />

Seasonal influenza, on the other hand, tends to seriously harm only the very young or the very<br />

old. The death <strong>of</strong> the respiratory lining that triggers fits <strong>of</strong> coughing accounts for the sore<br />

throat and hoarseness that typically accompany the illness. The mucus-sweeping cells are also<br />

killed, which opens up the body for a superimposed bacterial infection on top <strong>of</strong> the viral<br />

infection. This bacterial pneumonia is typically how stricken infants and elderly may die during<br />

flu season every year. Their immature or declining immune systems are unable to fend <strong>of</strong>f the<br />

infections in time.<br />

The resurrection <strong>of</strong> the 1918 <strong>virus</strong> <strong>of</strong>fered a chance to solve the great mystery. The reason the<br />

healthiest people were the most at risk, researchers discovered, was that the <strong>virus</strong> tricked the<br />

body into attacking itself—it used <strong>our</strong> <strong>own</strong> immune systems against us.<br />

Those who suffer anaphylactic reactions to bee stings or food allergies know the power <strong>of</strong> the<br />

human immune system. In their case, exposure to certain foreign stimuli can trigger a massive<br />

overreaction <strong>of</strong> the body’s immune system that, without treatment, could literally drop them<br />

dead within minutes. Our immune systems are equipped to explode at any moment, but there

are layers <strong>of</strong> fail-safe mechanisms that protect most people from such an overreaction. The<br />

influenza <strong>virus</strong> has learned, though, how to flick <strong>of</strong>f the safety.<br />

Both the 1918 <strong>virus</strong> and the current threat, H5N1, seem to trigger a “cytokine storm,” an<br />

overexuberant immune reaction to the <strong>virus</strong>. In laboratory cultures <strong>of</strong> human lung tissue,<br />

infection with the H5N1 <strong>virus</strong> led to the production <strong>of</strong> ten times the level <strong>of</strong> cytokines induced<br />

by regular seasonal flu <strong>virus</strong>es.194 The chemical messengers trigger a massive inflammatory<br />

reaction in the lungs. “It’s kind <strong>of</strong> like inviting in trucks full <strong>of</strong> dynamite,” says the lead<br />

researcher who first discovered the phenomenon with H5N1.195<br />

While cytokines are vital to antiviral defense, the <strong>virus</strong> may trigger too much <strong>of</strong> a good thing.<br />

196 The flood <strong>of</strong> cytokines overstimulates immune components like Natural Killer Cells, which<br />

go on a killing spree, causing so much collateral damage that the lungs start filling up with<br />

fluid. “It actually turns y<strong>our</strong> immune system on its head, and it causes that part to be the<br />

thing that kills you,” explains Osterholm.197 “All these cytokines get produced and [that] calls<br />

in every immune cell possible to attack y<strong>our</strong>self. It’s how people die so quickly. In 24 to 36<br />

h<strong>our</strong>s, their lungs just become bloody rags.”198<br />

People between 20 and 40 years <strong>of</strong> age tend to have the strongest immune systems. You<br />

spend the first 20 years <strong>of</strong> y<strong>our</strong> life building up y<strong>our</strong> immune system, and then, starting<br />

around age 40, the system’s strength begins to wane. That is why this age range is particularly<br />

vulnerable, because it’s y<strong>our</strong> <strong>own</strong> immune system that may kill you.199 A new dog learning old<br />

tricks, H5N1 may be following in the 1918 <strong>virus</strong>’s footsteps.200<br />

Either we wipe out the <strong>virus</strong> within days or the <strong>virus</strong> wipes out us. The <strong>virus</strong> doesn’t care<br />

either way. By the time the host wins or dies, it expects to have moved on to virgin territory—<br />

and in a dying host, the cytokine storm may even produce a few final spasms <strong>of</strong> coughing,<br />

allowing the <strong>virus</strong> to jump the burning ship. As one biologist recounted, the body’s desperate<br />

shotgun approach to defending against infection is “somewhat like trying to kill a mosquito<br />

with a machete—you may kill that mosquito, but most <strong>of</strong> the blood on the floor will be<br />

y<strong>our</strong>s.”201

“There is nothing permanent except change.”<br />

—Heraclitus<br />

Mutant swarm <strong>of</strong> influenza <strong>virus</strong>es<br />