THE BUSINESS & MANAGEMENT REVIEW - The Academy of ...

THE BUSINESS & MANAGEMENT REVIEW - The Academy of ...

THE BUSINESS & MANAGEMENT REVIEW - The Academy of ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

ISSN 2047-2854<br />

<strong>Academy</strong> <strong>of</strong> Business & Retail Management<br />

<strong>THE</strong> <strong>BUSINESS</strong> &<br />

<strong>MANAGEMENT</strong> <strong>REVIEW</strong><br />

Volume 2, Number 2<br />

www.abrmr.com

Executive Board Members<br />

Dr P R Datta, Executive Chair<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor P R Banerjee, Head <strong>of</strong> Research & Development, ABRMR<br />

Dr B.R.Chakraborty, Operations<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>. G. Dixon, Review Editor<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>. Lothar Auchte, Review editor<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>. Ogenyi Omar, Review-Editor<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>. Gairik Das, Review Editor<br />

Dr Soumitra N.Deb, Review Editor<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>. Fon Sim Ong, Review Editor<br />

Editorial Advisory Board<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>. G. Dixon, Pr<strong>of</strong>. A. Jayakumar, Pr<strong>of</strong>essor N.P Makarkin, Dr. Sudaporn Sawmong, Dr. John<br />

Dung-Gwom, Pr<strong>of</strong>. Victor Braga, Pr<strong>of</strong>. Luiz Alberto Alves dos Santos<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>. Mariia Sheluntcova, Pr<strong>of</strong>essor N.D Gooskova, Pr<strong>of</strong>essor P R Banerjee, Pr<strong>of</strong>. Dr. Hayri<br />

Ulgen, Dr. Saumitra N. Deb, Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Gairik Das, Pr<strong>of</strong>essor A.C Panday, Dr Nripendra Singh,<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>. Fon Sim Ong, Pr<strong>of</strong>. S. Rangnekar, Pr<strong>of</strong>. C. Michael Wernerheim, Pr<strong>of</strong>, srini Srinivasan<br />

Session Chairs<br />

Corporate Governance and Business Ethics<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>. Sal AmirKhalkhali<br />

<strong>The</strong> Growth and Economic Development<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>. Pr<strong>of</strong>. Marek Dziura<br />

HRM, Marketing and Information Technology<br />

Dr. P.R.Datta<br />

Ashru Bairagee-Project Manager & Research Fellow<br />

M Agalya-Research Executive<br />

i

Corporate Governance and Business Conference (CGBC)<br />

19-20 th July 2012<br />

Holiday Inn Boston-Somerville,<br />

30, Washington Street,<br />

Boston, MA, 02143, USA.<br />

Dear Conference Participants,<br />

It is my very great pleasure to welcome you to CGBC – Boston 2012. For some <strong>of</strong> you this will be<br />

your first visit to Boston and we trust that during your time with us you will gain fresh insights,<br />

engage in healthy discussions and forge new friendships in a spirit <strong>of</strong> academic enquiry. No one<br />

here present can be under any illusion that for many these are challenges times and the nature <strong>of</strong><br />

the global economy is such that it is beholden on academics to seek a broader understanding <strong>of</strong><br />

common themes and theories. <strong>The</strong> fall-out from the recent world economic crisis has been such<br />

that the issue <strong>of</strong> governance has moved centre stage. This 2 nd Boston conference on Corporate<br />

Governance and Business affords an opportunity to explore pressing issues in an international<br />

environment conducive to robust discussion and debate.<br />

I believe that we will all benefit from our engagement with the Conference and I trust that all<br />

concerned will have stimulating and intellectually enriching stay in Istanbul.<br />

With every good wish,<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor P. R. Banerjee<br />

Head <strong>of</strong> Research and Development<br />

<strong>Academy</strong> <strong>of</strong> Business and Retail Management (ABRM)<br />

ii

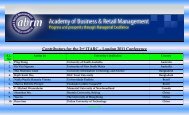

Sr.<br />

No.<br />

Contents<br />

Agenda & Articles<br />

Corporate Governance and Business Conference (CGBC)<br />

19-20 th July 2012<br />

Articles<br />

Agenda for Corporate Governance & Business Conference<br />

1 Board Governance Development for Civil Society Organisation: A Strategy for Systems<br />

1<br />

Strengthening and Sustainability<br />

2 Are Singapore Boards Global 7<br />

3 Corporate Governance in the Value Based Management Concept 13<br />

4 Investors` Reaction to the Implementation <strong>of</strong> Corporate Governance Mechanisms -<br />

5 Corporate Governance in Public Sector Banks-Tapping the Bee Hive 21<br />

6 Financial Reporting Standards as a Tool in Order to Ensure Corporate Transparency: <strong>The</strong> 25<br />

Case <strong>of</strong> Turkey<br />

7 Boardroom Pay, Performance and Corporate Governance in Malaysia 27<br />

8 An Analysis <strong>of</strong> Performance Appraisal Systems <strong>of</strong> Merchantile bank Limited 52<br />

9 On the Effectiveness <strong>of</strong> Quality Regulation: Some Empirical Results 53<br />

10 Compliance Versus Volatility <strong>of</strong> Performance in 2012, Corporate Influence in Bureaucratic<br />

Systems. Where Should the Focus for America lay Most<br />

59<br />

11 Exposing MBA Students to Corporate Governance 61<br />

12 Enterprise Restructuring in the Conditions <strong>of</strong> the Crisis and the Globalization Challenges.<br />

Based on the Experiences <strong>of</strong> the Polish Economy<br />

13 Corporate Governance and Performance <strong>of</strong> Commercial Banks in Nigeria 63<br />

14 Pr<strong>of</strong>it creation, intra and inter-generational Equity: Need for New Company Law 64<br />

15 <strong>The</strong> Publishing Scramble for Africa: A salutary tale <strong>of</strong> opportunity, bribery and censure 65<br />

16 A Panel Cointegration Approach to FDI and Growth in Africa: Evidences from ECOWAS,<br />

ECCAS, UMA, EAC and SADC Regions<br />

17 Technology Systems for Sustainable Development in Poland 78<br />

18 Risk in the Enterprise Value Creation 88<br />

19 Analysis <strong>of</strong> Causes and Consequences <strong>of</strong> the Global Economics Crisis –Poland`s Perspective 94<br />

Page<br />

20 <strong>The</strong> Disharmonies, Dilemmas and Effects <strong>of</strong> the Transformation <strong>of</strong> the Polish Economy 103<br />

21 Low Economic Awareness and Its Consequences: <strong>The</strong> Case <strong>of</strong> Turkey 112<br />

22 Ranking Indian States on Social Welfare & developmental Status in Globalisation Era using a<br />

MCDM Approach<br />

119<br />

23 Creating Consumer Based Brand Equity in Indian Sport Shoe Market 131<br />

24 A Conceptual Framework <strong>of</strong> Customer Retention Strategy (CRS) 139<br />

25 Reward or Penalty Inter-temporal Pricing <strong>of</strong> Decentralized Channel Supply Chain Under<br />

Asymmetric information Condition<br />

26 Succession Planning in Management Institutes: A critical Study 141<br />

27 Cultural Intelligence as Core Competency to Employability 142<br />

28 Opinion-Leading Role <strong>of</strong> Politically Aware Consumer 143<br />

62<br />

66<br />

140<br />

iii

Contents<br />

Agenda & Articles<br />

International Conference on Business & Economic Development (ICBED)<br />

23-24 th July 2012, Las Vegas, USA<br />

Sr.<br />

No.<br />

Articles<br />

Page<br />

Agenda for International Conference on Business & Economic Development<br />

1<br />

How Does Employee satisfaction Impact Information Flow during order fulfillment<br />

process<br />

151<br />

2<br />

An Exploration <strong>of</strong> Consumer Misbehaviours and their influences on Retail stores: An<br />

Application <strong>of</strong> the theory <strong>of</strong> Justice<br />

156<br />

3<br />

How Do Online Consumer Review Sentiments affect E-commerce Sales A Text Mining<br />

Analysis<br />

157<br />

4 Geographic Distribution <strong>of</strong> Population and Labor Force in Saudi Arabia 158<br />

5<br />

<strong>The</strong> Relationship Between Leadership and Learning Organisation: A Review <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Literature and Research Proposal<br />

168<br />

6 Relationship Marketing: Towards a Definition 174<br />

7 ERP System Implementation CSFs for Korean Organisations: A Delphi study 182<br />

8<br />

<strong>The</strong> Effects <strong>of</strong> Extrinsic Cues on the Relationship Between Brand Image and Purchasing<br />

Intention-Evidences from Chinese Exchabge Students` Perspective<br />

189<br />

9<br />

Employee Stock ownership and Employee Psychological ownership: <strong>The</strong> Moderating Role<br />

<strong>of</strong> Individual Characteristics<br />

190<br />

10 Adoption <strong>of</strong> Job Rotation as a Component <strong>of</strong> Staff Development in Polytechnics In Ghana 198<br />

11<br />

Water – <strong>The</strong> missing ingredient in real and sustained economic development<br />

209<br />

12<br />

Markets in Financial Instruments Europe Directive (MIFID): A Method <strong>of</strong> Controlling<br />

Ethical Banking<br />

210<br />

13<br />

Efficiency <strong>of</strong> EC Greenhouse Gas Abatement Measures and Firms in the European Union:<br />

Evidence from Plant Level Allocations and Surrendered Permits.<br />

220<br />

14 Corruption, Democracy and Tax Compliance: Cross-country Evidence 221<br />

15<br />

Are High Interest Loans a Debt Trap or Access to Credit Evidence from a Field<br />

Experiement <strong>of</strong> Payday Borrowers.<br />

231<br />

16<br />

<strong>The</strong> Expectations <strong>of</strong> Potential Acquirers <strong>of</strong> Real estate rights and decisions to Purchase<br />

property in times <strong>of</strong> Recesion<br />

232<br />

17<br />

<strong>The</strong> Role <strong>of</strong> Micro and Small Enterprise in Employment Opportunity and Poverty<br />

reduction in addis Ababa, Ethiopia: <strong>The</strong> Case <strong>of</strong> Addis ketema Sub City<br />

233<br />

18 Innovation Policy in Poland – Challenge for Intensive Growth 234<br />

19 Structural Changes and Development <strong>of</strong> the SME Sector in Poland after EU Membership 243<br />

20<br />

21<br />

22<br />

<strong>The</strong> Identification and Measurement <strong>of</strong> Financial Threats Vs the Causes <strong>of</strong> Insolvency in<br />

the period <strong>of</strong> Poland`s Economic Transformation<br />

Challenges <strong>of</strong> Sustainability and Urban Development in Nigeria: Reviewing the<br />

Millenium Development Goals<br />

Incentives to Encourage Social Environmental Responsible Corporate Actions:<br />

Willingness to pay for non-use value <strong>of</strong> Land-Case <strong>of</strong> Backpackers in Fiji<br />

255<br />

264<br />

265<br />

iv

Sr.<br />

No.<br />

Articles<br />

Page<br />

23<br />

Testing the Export-led Growth Hypothesis for Sub Saharan Africa Countries (SSA). A<br />

Panel Data Analysis<br />

24 Cross Country Analysis <strong>of</strong> GCC Economic Risk 267<br />

25 How to Transfer Knowledge to your work 278<br />

26 Enterprise Development under Globalisation and the New Economy Conditions 279<br />

27 Innovation in Enterprise Development Strategy 287<br />

28<br />

Research <strong>of</strong> Influencing Factors for Usage <strong>of</strong> Facebook Willingness-A case Study on<br />

College Students in the Tamsui Area<br />

29 Scientific Advance and Perceptions about the Effectiveness <strong>of</strong> Democracy in MENA 306<br />

30 What Explains Innovative Outcomes at the Start Up Stage 320<br />

31 Does Vice Pay A Traditional Investigation <strong>of</strong> “Irresponsible” Investing 321<br />

266<br />

296<br />

v

Corporate Governance and Business Conference (CGBC)<br />

19-20 th July 2012<br />

Holiday Inn Boston-Somerville,<br />

30, Washington Street,<br />

Boston, MA, 02143, USA.<br />

SCHEDULE FOR <strong>THE</strong> CONFERENCE 2012<br />

Tuesday 17 th July, 2012, thru Wednesday 18 th July, 2012<br />

Arrival and Independent traveling days in Boston, USA<br />

Thursday, 19 th July, 2012<br />

8.00 AM -9.00AM Registration<br />

Thursday 19 th July, 2012<br />

9.00AM-9.15AM<br />

OPENING ADDRESS & WELCOME<br />

9.15AM-13.00 PM<br />

Track: Corporate Governance and Business Ethics<br />

Session Chair: Sal AmirKhalkhali<br />

I<br />

II<br />

III<br />

IV<br />

V<br />

Board Governance Development for Civil Society Organisation: A Strategy for Systems<br />

Strengthening and Sustainability<br />

Anisa Ari Amunega, Sandra Osanmer and Abubakar Kurfi, Management<br />

Sciences for Health, Nigeria<br />

Are Singapore Boards Global<br />

Shital Jhunjhunwala and R.K Mishra, Institute <strong>of</strong> Public Enterprise, India<br />

Corporate Governance in the Value Based Management Concept<br />

Tomasz Rojek, Cracow University <strong>of</strong> Economics, Poland<br />

Investors` Reaction to the Implementation <strong>of</strong> Corporate Governance Mechanisms<br />

Nousheen Tariq Bhutta and Syed Zulfiqar Ali Shah, International Islamic University,<br />

Islamabad, Pakistan<br />

Corporate Governance in Public Sector Banks-Tapping the Bee Hive<br />

Mridula Sahay and S. Shiva Kumar, Amrita School <strong>of</strong> Business, Amrita Nagar, India<br />

vi

VI<br />

VII<br />

VIII<br />

IX<br />

X<br />

XI<br />

XII<br />

XIII<br />

XIV<br />

Financial Reporting Standards as a Tool in Order to Ensure Corporate Transparency: <strong>The</strong> Case <strong>of</strong><br />

Turkey<br />

N. Ata Atabey, Department <strong>of</strong> Business Administration, Selcuk University, Turkey and<br />

Huseyin Cetin, Department <strong>of</strong> Tourism management, Necmettin Erbakan University,<br />

Turkey<br />

Boardroom Pay, Performance and Corporate Governance in Malaysia<br />

Puan Yatim, UKM-Graduate School <strong>of</strong> Business, University <strong>of</strong> Kebangsaan, Malaysia<br />

An Analysis <strong>of</strong> Performance Appraisal Systems <strong>of</strong> Merchantile bank Limited<br />

Sheikh Abdur Rahim, Daffodil International University, Bangladesh<br />

On the Effectiveness <strong>of</strong> Quality Regulation: Some Empirical Results<br />

Sal AmirKhalkhali and Atul Dar, Saint Mary`s University, Halifax, Canada<br />

Compliance Versus Volatility <strong>of</strong> Performance in 2012, Corporate Influence in Bureaucratic<br />

Systems. Where Should the Focus for America lay Most<br />

David M Chapinski, School <strong>of</strong> Public Affairs and Administration, Rutgers University,<br />

Newark, USA<br />

Exposing MBA Students to Corporate Governance<br />

Patricia Miller Selvy, Bellarmine University, USA<br />

Enterprise Restructuring in the Conditions <strong>of</strong> the Crisis and the Globalization Challenges. Based<br />

on the Experiences <strong>of</strong> the Polish Economy<br />

Ryszard Borowiecki and Barbara Siuta-Tokarska Department <strong>of</strong> Economics and<br />

Organization <strong>of</strong> Enterprises, Cracow University <strong>of</strong> Economics, Poland<br />

Corporate Governance and Performance <strong>of</strong> Commercial Banks in Nigeria<br />

Olagunju Adebayo and Oluwa Temitope Mariam, Redeemer`s University,<br />

Nigeria<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>it creation, intra and inter-generational Equity: Need for New Company Law<br />

Olawale Ajai, Lagos Business School, Pan African University, Lagos, Nigeria,<br />

13.00-14.00<br />

BREAK FOR LUNCH<br />

Thursday 19 th July 2012<br />

14.00 PM-14.25 PM<br />

Key Note Speaker<br />

Mark T Jones<br />

Mark is a fervent internationalist, who is widely travelled. He has had a distinguished career in<br />

education and currently serves as the Director <strong>of</strong> External Affairs for Park Royal College. In the<br />

year 2000 he initiated and oversaw a major humanitarian venture into war-torn Sierra Leone,<br />

and then spent two years in the Middle East where he worked in Jordan (2002 – 2004). He<br />

vii

writes and speaks on a variety <strong>of</strong> subjects ranging from corporate governance to women’s health<br />

in the developing world.<br />

As well as being an orator <strong>of</strong> distinction, Mark believes that it is essential that we articulate our<br />

convictions with passion; in this regard he is eager to help the voice <strong>of</strong> others to be heard. He is a<br />

Legislative Leadership Training specialist, as well as being an advisor on Diaspora community<br />

engagement. He is the Co-Founder & Executive Director <strong>of</strong> the Horn <strong>of</strong> Africa Business<br />

Association (HABA) as well as sitting on the Board <strong>of</strong> the Kitenge Africa Foundation (Uganda),<br />

the Advisory Committee <strong>of</strong> the Expertise Forum (A Think Tank Society focusing on the<br />

Sustainable Development <strong>of</strong> South Asian Countries) and being Chair <strong>of</strong> Trustees <strong>of</strong> Daughters <strong>of</strong><br />

Eve. In 1994 he was elected a Freeman <strong>of</strong> the City <strong>of</strong> London, and is also a Fellow <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Chartered Management Institute.<br />

14.30 PM – 17.30<br />

Track: <strong>The</strong> Growth and Economic Development<br />

Session Chair: Pr<strong>of</strong>. Marek Dziura<br />

I<br />

A Panel Cointegration Approach to FDI and Growth in Africa: Evidences from ECOWAS,<br />

ECCAS, UMA, EAC and SADC Regions<br />

Rasheed Olajide Alao, Department <strong>of</strong> Economics, Adeyemi College <strong>of</strong> Education, Ondo,<br />

Nigeria<br />

II<br />

III<br />

IV<br />

VI<br />

VII<br />

VII<br />

Technology Systems for Sustainable Development in Poland<br />

Marek Dziura, Cracow University <strong>of</strong> Economics, Poland<br />

Risk in the Enterprise Value Creation<br />

Andrzei Tomasz Jaki, Cracow University <strong>of</strong> Economics, Poland<br />

Analysis <strong>of</strong> Causes and Consequences <strong>of</strong> the Global Economics Crisis –Poland`s Perspective<br />

Ryszard Borowiecki, Cracow University <strong>of</strong> Economics, Poland<br />

<strong>The</strong> Disharmonies, Dilemmas and Effects <strong>of</strong> the Transformation <strong>of</strong> the Polish Economy<br />

Jarosxaw Kagzmarek, Cracow University <strong>of</strong> Economics, Poland<br />

Low Economic Awareness and Its Consequences: <strong>The</strong> Case <strong>of</strong> Turkey<br />

Murat Arici, Department <strong>of</strong> Philosophy, Konya N.E University, Turkey<br />

Ranking Indian States on Social Welfare & developmental Status in Globalisation Era using a<br />

MCDM Approach<br />

Ayan Chattopadhya, IISWBM (aafiliated to Calcutta University), Kolkata, India and<br />

Arpita Banerjee Chattopadhya, Budge-Budge College (affiliated to Calcutta University),<br />

India.<br />

17.35PM<br />

CLOSING SPEECH FOR <strong>THE</strong> 1 st DAY CONFERENCE<br />

viii

Friday 20 th July, 2012<br />

10.00AM-10.15AM<br />

OPENING ADDRESS FOR DAY 2<br />

10.15 AM -13.00 PM<br />

Track: HRM, Marketing and Information Technology<br />

Session Chair: Dr P R Datta<br />

I<br />

II<br />

III<br />

IV<br />

V<br />

VI<br />

Creating Consumer Based Brand Equity in Indian Sport Shoe Market<br />

Ravindar Reddy and Chandrajeet Kumar, School <strong>of</strong> Management, National Institute <strong>of</strong><br />

Technology, Warangal, India<br />

A Conceptual Framework <strong>of</strong> Customer Retention Strategy (CRS)<br />

Palto Ranjan Datta, University <strong>of</strong> Hertfordshire, UK<br />

Reward or Penalty Inter-temporal Pricing <strong>of</strong> Decentralized Channel Supply Chain Under<br />

Asymmetric information Condition<br />

Weiping Liu, Department <strong>of</strong> Business Administration, Eastern Connecticut State<br />

University, USA<br />

Lindu Zhao, Southeast University, Nanjing, China<br />

Succession Planning in Management Institutes: A critical Study<br />

Priyanka Kulkarni and Arun Mokashi, MIT CoE, Centre for Management Studies and<br />

Research, Pune, India<br />

Cultural Intelligence as Core Competency to Employability<br />

Ruey-FaLIN, Nattawadee Korsakul and Nattharuja Korsakul, FengChia University,<br />

Taiwan<br />

Opinion-Leading Role <strong>of</strong> Politically Aware Consumer<br />

Mirza Ashfaq Ahmed, University <strong>of</strong> Gujrat, Pakistan and Suleman Aziz Lodhi<br />

Faculty <strong>of</strong> Management Sciences, Lahore Leads University, Pakistan<br />

13.00-14.00<br />

BREAK FOR LUNCH<br />

16.05 PM CLOSING SPEECH FOR <strong>THE</strong> CONFERENCE<br />

21 st April 2012<br />

<strong>The</strong>re will be no session or function scheduled for today. Please take this opportunity to<br />

explore Boston.<br />

ix

Board Governance Development for Civil Society Organizations:<br />

A Strategy for Systems Strengthening and Sustainability.<br />

Anisa Ari Amunega, Sandra Osanmor and Abubakar Kurfi<br />

PLAN -Health project, Management Sciences for Health, Abuja, Nigeria<br />

Keywords<br />

Board development, civil society organizations; sustainability, systems<br />

Abstract<br />

Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) in Nigeria play a critical role in transparency, accountability and<br />

responsiveness in the multi-sectoral approach to HIV/AIDS. CSO board members <strong>of</strong>ten lack knowledge <strong>of</strong> their roles<br />

and responsibilities and when they do fail to carry them out, which impacts negatively on organizational<br />

effectiveness. Management Sciences for Health (MSH), through the USAID-funded PLAN-Health Project in<br />

Nigeria, has developed an intervention to ensure strategic board governance programs promote transparency, social<br />

participation and accountability within Civil Society Organizations.<br />

Our strategy is rooted in a three stage process: defining roles and responsibilities; increasing knowledge and<br />

skills; and improving performance <strong>of</strong> board member’s roles and responsibilities. In the course <strong>of</strong> MSH PLAN-Health<br />

program implementation, organizations identified to receive technical support to strengthen their board were<br />

interviewed to ascertain the areas and level <strong>of</strong> support required. This resulted in a training programme to close<br />

identified governance gaps within these organizations.<br />

A total <strong>of</strong> thirty Board members were trained across two organizations. <strong>The</strong> structure <strong>of</strong> the training<br />

provided the opportunity for board members to start from the basic; vision, mission, and value statement which are<br />

the pillars <strong>of</strong> any organization. Members were also taken through various tools that will aid planning, scheduling<br />

and oversight in order to improve organizational performance.<br />

Capacity-building <strong>of</strong> Board members is a critical step to health systems strengthening and sustainability <strong>of</strong><br />

HIV Service Organizations in resource poor settings like Nigeria.<br />

Introduction<br />

Nigeria is the most populous country in Africa and was ranked third worst affected by<br />

HIV/AIDS in the world in 2003. Since the first case <strong>of</strong> HIV/AIDS in Nigeria was reported in 1986, there<br />

has been rapid increase in the total number <strong>of</strong> people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA). <strong>The</strong> national<br />

prevalence rose from 1.8% in 1991 to 5.8% in 2001 and reportedly declined to 5% in 2003 and 4.6% in 2008.<br />

Not only HIV but numerous other health indicators and outcomes have remained dramatically low in the<br />

country with the health related millennium development goals becoming obviously difficult and<br />

unrealistic to meet. <strong>The</strong> health sector in the country is characterized by the lack <strong>of</strong> stewardship;<br />

inadequate financing, weak health infrastructure and poor and ineffective coordination among all sectors<br />

in the nation’s health care system. In view <strong>of</strong> these challenges it is obvious that government alone cannot<br />

handle the complex task <strong>of</strong> providing affordable and qualitative health care to the populace, hence the<br />

need for the involvement <strong>of</strong> all stakeholders especially the civil society organizations.<br />

Civil society organizations denotes all those civil associations ; organizations, and networks that<br />

occupy the social space between governments and the families and the communities, this includes,<br />

community based organizations, faith based organizations and other channels <strong>of</strong> interactions like the<br />

traditional institutions that play a role in providing services to the populace such as private or voluntary<br />

unions, civic clubs, trade unions, gender clubs, cultural and religious groups, charities, social and sports<br />

clubs, cooperatives, environmental groups, pr<strong>of</strong>essional groups, consumer organizations and the media.<br />

Even though in Nigeria quantitative data on practically everything is difficult to come by, but there are<br />

<strong>The</strong> Business & Management Review, Vol.2 Number 2, July 2012<br />

1

indications That the civil society movement is one <strong>of</strong> the fastest growing sectors in the country, however<br />

growth and evolution <strong>of</strong> the civil society organizations is more dependent on the flow <strong>of</strong> foreign aid than<br />

on interests in specific areas <strong>of</strong> national development 6 .<br />

Civil society organizations play a critical role in translating government’s policies into actions by<br />

bridging the gap between public policy formulation and utilization ; they also serve as a pathway for<br />

facilitating community mobilization and sensitization as well as ensuring social and political<br />

accountability in the delivery <strong>of</strong> health services. In the multi-sectoral response to HIV and AIDS in<br />

Nigeria, civil society organizations help mostly in supporting the local and grass root dimension to the<br />

response in the country, with many <strong>of</strong> the most innovative initiatives to address HIV/AIDS been<br />

designed and implemented by civil society groups with little or no external support 7 .<br />

<strong>The</strong> increasing role <strong>of</strong> HIV and AIDS to global morbidity and mortality has led to the huge outcry<br />

by people for involvement in the affairs <strong>of</strong> HIV/AIDS response globally and at national level. Civil society<br />

have been seen as a way <strong>of</strong> enforcing the bottom up pathway <strong>of</strong> health care provision where people will<br />

be responsible for taking the initiative to determine the type <strong>of</strong> health care they need which led the WHO<br />

to form the first civil society platform by the world health organization in 2001 8 . Civil society if rightfully<br />

engaged can be a veritable platform for bringing in more equity into health service provision bearing in<br />

mind that governments and international donor organizations have largely failed to reach the most<br />

vulnerable and hard to reach populations which is a major prerequisite in providing health care for all.<br />

HIV/AIDS has become a manageable chronic illness rather than the terminal illness it was<br />

perceived to be in the past, this is mainly due to increased availability <strong>of</strong> ART. It has therefore become<br />

necessary for such gains to be sustained as this is a very important determinant <strong>of</strong> patient outcome. Civil<br />

society is vital in ensuring that patients have the best in terms <strong>of</strong> care and support and overall service<br />

provision. Being a chronic illness with a lot <strong>of</strong> stigma still associated with it, HIV/AIDS has social and<br />

economic implications on patients on ART, even though the drug itself is free in most settings. It is<br />

important to get the perspectives <strong>of</strong> those accessing and taking the treatment to inform policy; and indeed<br />

also obtain the perspectives <strong>of</strong> those delivering and funding the treatment programs, civil society<br />

organizations can do just this and more.<br />

Efforts by non-governmental organizations have been criticized by numerous stakeholders as<br />

been non sustainable in view <strong>of</strong> dwindling global support for HIV and AIDS services. But these comments<br />

tend to assess the local approaches <strong>of</strong> civil society engagement in isolation from wider factors, such as the<br />

existence or absence <strong>of</strong> supportive national health policies that attempts to insulate the csos from this<br />

challenges 7 . <strong>The</strong> predominant challenges confronting civil society engagement in Nigeria are numerous;<br />

some <strong>of</strong> which include lack <strong>of</strong> coordination among them, weak or dwindling funds; inadequate human<br />

resources, exclusion <strong>of</strong> civil society from the decision making process at the national level and above all<br />

poor or deficient oversight by the members <strong>of</strong> the board <strong>of</strong> these organizations. <strong>The</strong> board is a sine qua<br />

non to the evolution, development and functionality <strong>of</strong> civil society organizations and is responsible for<br />

maintaining and making strategic decisions on the organizations objectives, policies and procedures as<br />

well as ensuring proper compliance with laid down rules and regulations for the overall success <strong>of</strong> the<br />

organization. Every nonpr<strong>of</strong>it organization needs a strong foundation <strong>of</strong> compliance and a broad<br />

organizational awareness <strong>of</strong> laws and regulations related to fundraising, Conflict <strong>of</strong> interest, financial<br />

accountability, human resources, lobbying, political advocacy and taxation. However, the information and<br />

concepts apply broadly to all types <strong>of</strong> nonpr<strong>of</strong>it boards. Because <strong>of</strong> the diversity by size and maturity <strong>of</strong><br />

different Organizations, each organization must determine whether or not an individual practice is<br />

appropriate for its current situation. Board members and employees become involved with a nonpr<strong>of</strong>it<br />

because <strong>of</strong> the organization’s public benefit mission. <strong>The</strong>refore the continued success <strong>of</strong> nonpr<strong>of</strong>it<br />

organizations requires broad public support and confidence which is the specific remit <strong>of</strong> board members.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Business & Management Review, Vol.2 Number 2, July 2012<br />

2

<strong>The</strong> principles for good governance and ethical practice, which are designed to guide board<br />

members and staff leaders <strong>of</strong> every non -pr<strong>of</strong>it organization as they work to improve their own operations<br />

enables the board and staff leaders <strong>of</strong> every organization to examine these principles carefully and<br />

determine how best they should be applied to their own operations. Many organizations will find that<br />

they already follow—or go beyond—these principles. Others may wish to make changes in their current<br />

practices over time, and some may conclude that certain practices do not apply to their operations. <strong>The</strong><br />

purpose is to reinforce a common understanding <strong>of</strong> transparency, accountability, and good governance<br />

for the sector as a whole—not only to ensure ethical and trustworthy behavior, but equally important, to<br />

spotlight strong practices that contribute to the effectiveness, durability, and broad popular support for<br />

organizations <strong>of</strong> all kinds. Still, given the wide, necessary diversity <strong>of</strong> organizations, missions, and forms<br />

<strong>of</strong> activity that make up the nonpr<strong>of</strong>it community, it would be unwise, and in many cases impossible, to<br />

create a set <strong>of</strong> universal standards to be applied uniformly to every organization Instead, it is<br />

recommended that the following set <strong>of</strong> principles serve as a guideposts for every organization, adopting<br />

specific practices that best fit its particular size and organization’s purpose to evaluate their current<br />

standards.<br />

This study attempts to highlight those critical steps necessary for the designing and<br />

implementation <strong>of</strong> a capacity building intervention for the board <strong>of</strong> civil society organizations in low<br />

income nations like Nigeria as designed by Management Sciences for Health, and how if rightly applied<br />

this process can lead to the strengthening <strong>of</strong> the systems <strong>of</strong> these organizations to effectively govern<br />

themselves and scale-up HIV service-delivery, improve country-ownership, and promote long-term<br />

sustainability.<br />

Methodology<br />

Numerous Board members were trained across various organizations providing HIV and AIDS services in<br />

Nigeria, with support from the USAID funded PLAN Health project that is being implemented by<br />

management sciences for health. Our intervention strategy was based on the assumption that Board<br />

members will progress through three major stages:<br />

Analysis <strong>of</strong> the stages:<br />

As an entry point, the governance team carries out a consultative visit to better understand the<br />

governance structure, in terms <strong>of</strong> composition and how the Board carries out its operations as well as the<br />

Boards mental models, this <strong>of</strong> course varies bearing in mind the different contexts and dynamics <strong>of</strong> these<br />

organizations. This is imperative to understand the internal and external factors affecting the governance<br />

systems.<br />

<strong>The</strong> second step is conducting an assessment using governance assessment tool. This is a tool<br />

which gives an in depth exposition <strong>of</strong> the gaps in the board composition and operations. Prior to this,<br />

there is an overall organizational assessment conducted using the Management Sciences for Health<br />

<strong>The</strong> Business & Management Review, Vol.2 Number 2, July 2012<br />

3

Management and Organizational Sustainability Tool (MOST), this is a participatory assessment process<br />

for identifying an organization’s management needs and making concrete plans for improvement. <strong>The</strong><br />

MOST tool brings out the basic gaps at the periphery and actually identifies the organizational systems<br />

that needs to be strengthened, that is why the team has to go further in administering the Board<br />

governance assessment tool to illuminate specific gaps in governance practices.<br />

<strong>The</strong> third step is the design <strong>of</strong> intervention, basically the results from the assessment informs the<br />

design <strong>of</strong> intervention. This guides the team on what needs to be addressed, the area <strong>of</strong> focus for<br />

strengthening and what type <strong>of</strong> intervention will be appropriate. For some organizations, it could be just<br />

providing technical assistance in form <strong>of</strong> coaching and mentoring while for some it could be training in<br />

workshop setting or both. We could even go further in providing technical assistance in developing<br />

governance/guidance documents and support in governance enhancement plans. This stage <strong>of</strong> designing<br />

intervention is really critical because a whole lot <strong>of</strong> factors and determinants need to be considered for<br />

example, the Board composition, in terms <strong>of</strong> the level <strong>of</strong> literacy, mental models, and priorities.<br />

Simultaneously, the variable the capacity building team wants to change is key.<br />

<strong>The</strong> fourth step is the actual implementation <strong>of</strong> the intervention depending on what is most<br />

appropriate for the organization. <strong>The</strong> team mostly utilized training in a workshop setting and makes it<br />

participatory and really interactive, with a shift from the traditional training program which places so<br />

much emphasis on theories, to a program designed specially to have a real life impact on the participants<br />

with an eye on the beneficiaries, that is the organization and the community at large. It involves learning,<br />

reflecting and practicing what they have learnt. Information from the first visit gives the facilitator some<br />

sort <strong>of</strong> internal connection to the standards and operations <strong>of</strong> the organization and helps in linking their<br />

mission, vision, values and goals to the training, and from experience, it has made the training climate<br />

relaxing and intriguing. . A Standard <strong>of</strong> ethics manual for Board operations was adapted and used during<br />

the trainings. This document is designed to support the effective functioning <strong>of</strong> non-pr<strong>of</strong>it boards by<br />

recommending specific best practices, which are designed to guide board members and staff leaders <strong>of</strong><br />

every non -pr<strong>of</strong>it organization as they work to improve their own operations, it also enables the board and<br />

staff leaders <strong>of</strong> every organization to examine these principles carefully and determine how best they<br />

should be applied to their own operations. At the end <strong>of</strong> the trainings, the Board develops an action plan<br />

or Board work plan to close identified governance gaps within the organizations .This forms the Board<br />

calendar that guides Board activities and timelines for a year or six months (also depends on what the<br />

organization wants).<br />

<strong>The</strong> fifth step is basically following up with the action plans developed and providing feedback<br />

on how responsive they are in its implementation. Technical assistance is provided to support the Board<br />

on areas that they might be facing challenges. This is a continuous process until the governance system is<br />

really functional, both financially and programmatically. At this point, they are left to sustain the<br />

intervention themselves. (<strong>The</strong> PLAN –Health Project calls this “weaning <strong>of</strong>f”)<br />

Board governance training methodology/process<br />

<strong>The</strong> Business & Management Review, Vol.2 Number 2, July 2012<br />

4

Early Indicators <strong>of</strong> success<br />

An immediate result gotten from this intervention was an increase in knowledge and<br />

understanding <strong>of</strong> their roles and responsibilities evidenced by improved governance cycle <strong>of</strong> the<br />

organization. <strong>The</strong> governance practices and processes improved evidenced by locally-led development <strong>of</strong><br />

Board policy manuals, fundraising policies, organizational plans and other governance documents. <strong>The</strong><br />

Boards were also able to rebrand the image <strong>of</strong> the organizations, developed and reviewed vision, mission<br />

and value statements and had documented delineations <strong>of</strong> roles and responsibilities. <strong>The</strong> latter fostered<br />

team vitality and cohesion which is essential for any form <strong>of</strong> progress in achieving the goals <strong>of</strong> the<br />

organization and having a real impact on the beneficiaries<br />

<strong>The</strong> overall systems <strong>of</strong> the organizations have also been affected, no doubt by the shift in mental<br />

models <strong>of</strong> the Board. Policies never used have been reviewed and usage encouraged and enforced with<br />

more coordinated way <strong>of</strong> carrying out activities with a focus on results. This has eventually to an<br />

improvement in the provision <strong>of</strong> comprehensive HIV and AIDS services to the communities.<br />

Discussions<br />

Our methodology towards strengthening Board governance for civil society organizations in<br />

Nigeria focuses on building accountability, transparency, ownership, community linkages/engagement,<br />

Board activism and leadership. <strong>The</strong> success <strong>of</strong> this methodology counters the other methodologies that<br />

focus on only governance or operation practices <strong>of</strong> Board. <strong>The</strong> PLAN-Health approach challenges nonpr<strong>of</strong>it<br />

to consider alternative approaches to building organizational Board governance outside the<br />

traditional theoretical method <strong>of</strong> Board development to a more practical way that will have a huge and<br />

lasting impact on the Board, where creativity and problem solving practices is encouraged through a<br />

process <strong>of</strong> reflection and putting into practice what they have learnt towards achieving their overall<br />

organizational goals.<br />

From our experience board trainings with high dependency on theoretical means only serves as a<br />

quick fix as it is common to have re-occurring problems that perpetuate Board dysfunctions which is<br />

evidenced in poor team spirit, poor understanding <strong>of</strong> roles and responsibilities and ultimately poor Board<br />

performance. But our approach which hinges more on experiential method in the delivery <strong>of</strong> training<br />

allows members, who have not had the chance to work with other members to feel relaxed and open to<br />

share, learn, internalize and find ways to improve the boards operations and governance practices.<br />

Sadly, the state <strong>of</strong> the board governance development has not moved forward as have other areas<br />

<strong>of</strong> nonpr<strong>of</strong>it capacity building. Many boards still look to “board training” as the solution to its problems<br />

and far too many consultants continue to rely on outdated generic tools that go for the “quick fix,” rather<br />

than address underlying problems with the governance structure. <strong>The</strong> structure <strong>of</strong> most <strong>of</strong> the boards we<br />

have worked with are such that it is difficult to clearly state their roles and responsibilities, this is evident<br />

in the operations <strong>of</strong> the Board as board members involve themselves in the day to day management <strong>of</strong> the<br />

<strong>of</strong>fice and the implementation <strong>of</strong> programs. It is therefore important for board trainings to be adapted to<br />

meet the peculiar gaps identified following the board assessment. MSH –PLAN-health designs its<br />

trainings to suit the needs <strong>of</strong> specific boards, which is not a quick fix method as board members a involve<br />

in identifying their challenges and pr<strong>of</strong>fering actionable steps to address them.<br />

Conclusion<br />

In financial constraint settings, it is essential for the leaders <strong>of</strong> non-pr<strong>of</strong>it organizations to govern<br />

and lead their organizations in ways that will continuously build the confidence and trust <strong>of</strong> its<br />

beneficiaries, staff, funders, community and stakeholders at large. This is imperative if such organizations<br />

would stand the test <strong>of</strong> time and provide sustainable interventions because invariably, development funds<br />

and partners will not always be there. <strong>The</strong>refore, Capacity-building <strong>of</strong> Board members is a critical step to<br />

health system strengthening and sustainability <strong>of</strong> HIV Service Organizations. <strong>The</strong> organizations we have<br />

<strong>The</strong> Business & Management Review, Vol.2 Number 2, July 2012<br />

5

worked with demonstrated this as they effectively carry out their roles and responsibilities towards the<br />

board and the organization at large.<br />

Research limitations and directions for future research<br />

1. Even though the findings have shown that board development is critical to effective functioning <strong>of</strong><br />

civil society organizations; the challenge <strong>of</strong> organizations depending mostly on donor agencies to<br />

finance this kind <strong>of</strong> interventions makes it difficult to sustain.<br />

2. <strong>The</strong> research is more <strong>of</strong> a description <strong>of</strong> the process and the early indicators <strong>of</strong> success for the board<br />

development <strong>of</strong> these organizations, there is need to carry out further research to track how this<br />

interventions have directly benefited the communities these organizations serve.<br />

3. <strong>The</strong> challenges <strong>of</strong> funding to scale up the provision <strong>of</strong> such support to other grass root community<br />

based organizations and faith based organizations working in all sectors <strong>of</strong> health care not just HIV<br />

and AIDS in view <strong>of</strong> the obvious gains arising from it.<br />

4. Civil society organizations do not exist in isolation as a result they are subject to the influence <strong>of</strong> all<br />

the factors affecting the health system <strong>of</strong> the nation. This may affect the nature and benefit <strong>of</strong> this<br />

kind <strong>of</strong> intervention<br />

References<br />

Federal Ministry <strong>of</strong> Health, Nigeria; National Situation Analysis <strong>of</strong> the Health Sector Response to HIV and<br />

AIDS in Nigeria; FMOH/NASCP 2005; 1-198.<br />

UNAIDS AIDS epidemic update: Global summary <strong>of</strong> the AIDS epidemic 2009<br />

World Health Organization, UNAIDS and UNICEF 2010. Towards Universal Access: Scaling up priority<br />

HIV/AIDS interventions in the health sector. 2010 Progress Report. World Health Organization, UNAIDS and<br />

UNICEF 2010<br />

Gladys M, D. Mukurazita H. Jackson A; A review <strong>of</strong> household and community responses to the HIV/AIDS<br />

epidemic in the rural areas <strong>of</strong> sub-Saharan Africa (UNAIDS: Geneva, 1999), available at http://<br />

www.unaids.org/publications/documents/economics/agriculture/una99e39.pdf, last accessed 2 June 2012.<br />

B Rau; Politics <strong>of</strong> Civil Society in Confronting HIV and AIDS; Journal <strong>of</strong> International Affairs; 82.2 ; 2006<br />

Greet P; Laura M; Mary A. T; Saly S M; S<strong>of</strong>ia G; Increasing Civil Society Participation in the National HIV<br />

Response: <strong>The</strong> Role <strong>of</strong> UNGASS Reporting; J Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome Volume 52, Supplement 2,<br />

December 1, 2009<br />

Abdulazeez Y, Ismail B, Institutional Responses and the People Living with HIV/AIDS in Nigeria: <strong>The</strong> Gaps in<br />

Sustainable Prevention, Mitigation, Care and Support; European Journal <strong>of</strong> Social Sciences – Volume 17, Number 3<br />

(2010)<br />

Action Aid Nigeria; Integrated HIV /AIDS , Tuberculosis and Malaria (ATM) response resource kit for civil<br />

society organizations in Nigeria; 2010<br />

Judy Transforming the works <strong>of</strong> the Boards; Moving toward community driven governance, December, 2005<br />

Principles and practices <strong>of</strong> non-pr<strong>of</strong>it excellence; A guide for non-pr<strong>of</strong>it Board members, managers and staff.<br />

Minnesota Council <strong>of</strong> non-pr<strong>of</strong>it, 2010<br />

Acknowledgement<br />

<strong>The</strong> authors wish to acknowledge all the staff <strong>of</strong> the Program to build Leadership and Accountability in the<br />

Nigerian Health sector (PLAN-Health), Management Sciences more specifically Barry Smith, who believed in me and<br />

generously shared insights , wisdom and materials gathered from vast experience working in various international<br />

Boards. I would also like to thank Ochanya Iyaji-Paul, a HIV/AIDS community care advisor, with the PROACT<br />

project who prodded me to document the work I carry out with the Board <strong>of</strong> organizations.<br />

Special gratitude goes to the Board and members <strong>of</strong> Gede foundation and Lawanti Community Development<br />

Foundation who were open to learning and created an enabling environment for this intervention.<br />

Source <strong>of</strong> Funding<br />

<strong>The</strong> intervention that gave rise to this article was supported by the United States Presidents’ Emergency Plan<br />

for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) under the terms<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Program to build Leadership and Accountability in Nigeria’s Health System (PLAN-Health), Associate award<br />

No. 620-A-00-10-0009-00 under the Cooperative Agreement No. GPO-A-00-05-0024<br />

<strong>The</strong> Business & Management Review, Vol.2 Number 2, July 2012<br />

6

Are Singapore Boards Global<br />

Shital Jhunjhunwala<br />

Institute <strong>of</strong> Public Enterprise, India<br />

&<br />

R.K. Mishra<br />

Director, Institute <strong>of</strong> Public Enterprise, India<br />

Keywords<br />

Regional Diversity, Board Diversity, International Directors.<br />

Abstract<br />

While there is a rising acceptance that to be effective boards should be diverse, study <strong>of</strong> diversity is mostly limited to<br />

race or gender. This paper examines regional diversity <strong>of</strong> corporate boards <strong>of</strong> Singapore. Singapore boards do not<br />

have global representation but are biased towards local directors. Need for relevant talent on board appears to be a<br />

major reason to appoint international directors. <strong>The</strong> study did not find a strong relationship between boards’<br />

globalization and its size.<br />

Research Need and Objective<br />

<strong>The</strong>re is a growing belief that heterogeneous boards with wide range or skills, view points,<br />

experience and different ways <strong>of</strong> thinking will result in higher levels <strong>of</strong> boards’ productivity and<br />

effectiveness. Research in this respect has mainly focused on gender and race diversity suggesting that<br />

increase <strong>of</strong> women and minorities on boards improves their performance. Diversity goes beyond race and<br />

gender to encompass age, experience, ethnicity, lifestyle, culture, education, religion and many other<br />

facets that make each <strong>of</strong> us unique as individuals.<br />

In this paper we examine whether Singapore Boards are regionally diverse in terms <strong>of</strong> having<br />

global representation. People from different countries have different cultural and upbringing background.<br />

Further as businesses are now global, having a board that understands how different countries operate,<br />

their business environment and people is a necessity.<br />

Research Methodology<br />

To explore regional diversity in Singapore boards we asked the following research questions -<br />

1. Level <strong>of</strong> Global Representation<br />

2. Does talent and skill need increase regional diversity<br />

3. Impact <strong>of</strong> Board Size on Regional Diversity<br />

<strong>The</strong> sample consisted <strong>of</strong> 302 directors from 29 <strong>of</strong> the 30 Straits Times Index (STI) companies, the<br />

major index <strong>of</strong> Singapore for the year 2010. (Information on one company could not be obtained). Data<br />

was collected using Content analysis from annual reports and websites <strong>of</strong> the companies under study. <strong>The</strong><br />

country with which they spent the early years <strong>of</strong> life (referred to as country <strong>of</strong> origin or belonging<br />

henceforth) has been considered and not the country <strong>of</strong> residence or citizenship. <strong>The</strong>re country <strong>of</strong> origin<br />

has been estimated based on appearance, name, and early education. Country <strong>of</strong> 28 directors <strong>of</strong> the 302<br />

directors could not be identified making the final sample size <strong>of</strong> directors 274.<br />

Level <strong>of</strong> Global Representation<br />

As many as 24% <strong>of</strong> the boards have directors only from Singapore and more than ¾ had at list one<br />

international Director. (Figure 1) 55% <strong>of</strong> the 200 largest US companies have no non-US director 1 . At the<br />

same time 28% <strong>of</strong> the Singapore boards have directors representing 5 or more countries. Thus Singapore<br />

boards are more regionally disperse than US companies with some boards being more regionally diverse<br />

than others.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Business & Management Review, Vol.2 Number 2, July 2012<br />

7

Figure 1<br />

Regional Diversity <strong>of</strong> Boards<br />

NA<br />

10%<br />

6 Countries<br />

14%<br />

5 Countries<br />

14%<br />

4 Countries<br />

14%<br />

3 Countries<br />

10%<br />

2 Countries<br />

14%<br />

1 Country<br />

24%<br />

Figure 2<br />

Regional Dispersion<br />

0.7<br />

0.8<br />

0.7<br />

0.6<br />

0.6<br />

0.5<br />

0.4<br />

0.3<br />

0.2<br />

0.5<br />

0.1<br />

0<br />

Proportion <strong>of</strong> Directors<br />

0.4<br />

0.3<br />

0.2<br />

Local<br />

SEA & China & Singapore<br />

Other Asian Counties<br />

UK<br />

USA & Canada<br />

Europe<br />

Africa<br />

Australia & New Zeland<br />

South America<br />

0.1<br />

0<br />

Singapore SEA & China Other Asian<br />

Counties<br />

UK USA & Canada Europe Africa Australia &<br />

New Zeland<br />

Region<br />

South America<br />

As expected more than 60% <strong>of</strong> the directors belong to Singapore. (Figure 2) With South East<br />

Asian countries being the number two with almost 13 % share. More than 1/3 <strong>of</strong> the directors were from<br />

other countries. Only 6% <strong>of</strong> US directors are non-US. Some <strong>of</strong> the companies listed on STI are based in<br />

other countries particularly Hong Kong, Malaysia & Indonesia. When comparing directors’ country to<br />

country <strong>of</strong> the company the share <strong>of</strong> directors being local increased by about 4% (64.6 % to 68.2%).<br />

Unmistakably companies prefer local directors to directors from foreign countries. More than 82% <strong>of</strong> the<br />

directors were from Asia. Another 13% were from USA or UK. Less than 5% come from other parts <strong>of</strong> the<br />

world. <strong>The</strong> study <strong>of</strong> US companies had shown the <strong>of</strong> the non- US directors about 50% were from UK or<br />

Canada, 20% from Europe (Germany, France and Netherlands) and another 8% from Australia all western<br />

countries with little representation from Asia.<br />

Gender inequality is obvious with female directors being restricted to Singaporeans. In case <strong>of</strong> male<br />

directors only 62 % <strong>of</strong> the directors were from Singapore.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Business & Management Review, Vol.2 Number 2, July 2012<br />

8

Table 1: Duration on Board<br />

Home<br />

Duration years Country Other Countries<br />

Average 7 6<br />

Maximum 44 22<br />

Less Than 1 year 13% 20%<br />

1-20 years 79% 76%<br />

More than 20 years 8% 5%<br />

Directors from home country had served on the board <strong>of</strong> the company longer than directors from<br />

others countries with the maximum duration being double. (Table 1) 7% more <strong>of</strong> the directors from other<br />

countries had been on the board for less than one year and 3% less had been serving the board for more<br />

than 20 years implying a bias in favour <strong>of</strong> directors from home country. It also suggests that globalization<br />

<strong>of</strong> Singapore Boards has gained prominence only in recent years.<br />

Figure 3<br />

Regional Represention by Status<br />

100%<br />

90%<br />

80%<br />

2%<br />

0%<br />

2%<br />

2%<br />

13%<br />

9%<br />

0%<br />

8%<br />

12%<br />

8%<br />

2% 0%<br />

2%<br />

2%<br />

5%<br />

5%<br />

3%<br />

9%<br />

80%<br />

70%<br />

60%<br />

50%<br />

40%<br />

30%<br />

Executive<br />

Non-<br />

Executive<br />

Independent<br />

Percentage <strong>of</strong> Directors<br />

70%<br />

60%<br />

50%<br />

40%<br />

30%<br />

28%<br />

12%<br />

60%<br />

72%<br />

20%<br />

10%<br />

0%<br />

Other Asian Counties<br />

Local<br />

SEA & China & Singapore<br />

UK<br />

USA & Canada<br />

Europe<br />

Africa<br />

Australia & New Zeland<br />

South America<br />

20%<br />

45%<br />

Singapore<br />

Other Asian Counties<br />

SEA & China<br />

UK<br />

10%<br />

USA & Canada<br />

Europe<br />

Africa<br />

Australia & New Zeland<br />

0%<br />

Executive Non-Executive Independent<br />

Status<br />

South America<br />

As almost 65% <strong>of</strong> the directors are from Singapore it is no surprise that 60% <strong>of</strong> non- executive and 72% <strong>of</strong><br />

independent directors were from Singapore. What appears unusual is that only 45% <strong>of</strong> the executives are<br />

from Singapore. Executive directors tend to be from the same country as the where the company is based.<br />

In fact 64% <strong>of</strong> the executive directors are <strong>of</strong> local origin. (Figure 3)<br />

Table 2: Status break up for regions<br />

Non-<br />

Region<br />

Executive Executive Independent<br />

Singapore 12% 20% 68%<br />

Local 16% 21% 63%<br />

SEA & China 37% 20% 43%<br />

SEA & China & Singapore<br />

16% 16% 68%<br />

Other Asian Counties 29% 36% 36%<br />

UK 29% 33% 38%<br />

USA & Canada 7% 33% 60%<br />

Europe 20% 0% 80%<br />

Africa 0% 0% 100%<br />

Australia & New Zealand 0% 0% 100%<br />

South America 100% 0% 0%<br />

<strong>The</strong> Business & Management Review, Vol.2 Number 2, July 2012<br />

9

Of all the Singaporeans on boards 12% are executives, 20% non-executives and as much as 68%<br />

are independent directors. (Table 2) 35% <strong>of</strong> Asians directors (other than Singapore) were executive<br />

directors. This suggests that in selection <strong>of</strong> executive directors’ talent and ability to run the company gets<br />

more importance than country they belong to.<br />

Figure 4:<br />

Country <strong>of</strong> Chairman and CEO/MD<br />

Chairman<br />

CEO/MD<br />

UK, 10%<br />

SEA, 10%<br />

India, 0%<br />

HK/China,<br />

7%<br />

Others/NK<br />

, 0%<br />

Singapore,<br />

72%<br />

Others/N<br />

K, 18%<br />

UK, 4%<br />

SEA, 4%<br />

India, 7%<br />

HK/China,<br />

14%<br />

Singapore<br />

, 54%<br />

Singapore<br />

HK/China<br />

India<br />

SEA<br />

UK<br />

Others/NK<br />

When it came to selection <strong>of</strong> Chairman, Singaporeans were definitely the first preference (72%).<br />

In contrast about half the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) /Managing Director were not from Singapore.<br />

Table 3: Top Man: Local or Global<br />

Home Country Other Countries<br />

Chairperson 97% 3%<br />

CEO/MD 77% 23%<br />

*UK Chairpersons to Hong Kong based companies were considered as home Country as these<br />

companies were build and grew during the period HK was under the control <strong>of</strong> UK<br />

Is the top man from the home country With the exception <strong>of</strong> one company (Singtel) chairman<br />

was from the home country <strong>of</strong> the Company. CEO’s were slightly more broad-based with 23% being<br />

foreigners.<br />

Talent and Skill<br />

Companies are besieged with a huge talent gap that extends all the way up to the boardroom.<br />

Companies need talented, experienced and able directors who have the skills to meet new challenges and<br />

add immense value to the organization. <strong>The</strong> question arises that do companies widen their search to<br />

include international directors to fill this need.<br />

Figure 5<br />

Qualification vs Country<br />

45%<br />

44%<br />

40%<br />

35%<br />

30%<br />

34%<br />

25%<br />

27%<br />

23%<br />

20%<br />

21%<br />

18%<br />

15%<br />

14%<br />

10%<br />

5%<br />

9%<br />

3% 0%<br />

3% 4%<br />

0%<br />

Doctorate Pr<strong>of</strong>essional Post Graduate Graduates Civil Servants Diploma<br />

Qualification<br />

Home Country Other Countries<br />

*Only highest qualification considered<br />

<strong>The</strong> Business & Management Review, Vol.2 Number 2, July 2012<br />

10

Comparison between directors from home and other countries show that international directors<br />

are given preference if they have higher qualifications. 5% and 11% more foreign directors were<br />

doctorates or post graduates respectively than local directors. 44% <strong>of</strong> the local directors were graduates<br />

against 27% <strong>of</strong> the foreign directors. (Figure 5)<br />

<strong>The</strong> experiences <strong>of</strong> directors are classified into four categories. First those directly related to<br />

business, say marine experience <strong>of</strong> a board member in companies doing marine business. Secondly,<br />

experience that is closely associated to the company’s business, for instance investment experience <strong>of</strong> a<br />

director in a banking company or a board member in a company in the resort business who is an architect<br />

is considered related experience. Third are Directors with functional experience like accounting,<br />

marketing and law. Finally those directors whose experience is unrelated have no obvious linking to the<br />

nature <strong>of</strong> company’s business.<br />

Figure 6<br />

Experience vs. Country<br />

40%<br />

35%<br />

30%<br />

25%<br />

20%<br />

15%<br />

10%<br />

37%<br />

5%<br />

0%<br />

7%<br />

27%<br />

8%<br />

34%<br />

Direct<br />

Related<br />

Functional<br />

Nature <strong>of</strong> Experience<br />

40%<br />

31%<br />

Not Related<br />

16%<br />

Other Countries<br />

Home Country<br />

37% <strong>of</strong> international directors had experience directly related to the business <strong>of</strong> the company and<br />

40% had functional expertise. 10% less local board members had direct experience and almost double had<br />

experiences not related to the company activities. (Figure 6) Further all foreign CEO’s had significant<br />

expertise in the company’s business.<br />

An analysis <strong>of</strong> the age <strong>of</strong> board members suggests that directors from foreign countries are<br />

younger on an average by 3 years. 15% <strong>of</strong> local directors were more than 70 years old in contrast, only 6%<br />

international directors were more than 70 years old. 16% <strong>of</strong> international directors were young (less than<br />

50 years), double the local (8%) young directors. (Table 4)<br />

Table 4: Board Age<br />

Home<br />

Age<br />

Country Other Countries<br />

Minimum 43 39<br />

Maximum 82 74<br />

Range 39 35<br />

Average 60 57<br />

Less than 50 8% 16%<br />

50-69 years 77% 77%<br />

70 or more 15% 6%<br />

* based on 107 directors<br />

<strong>The</strong> Business & Management Review, Vol.2 Number 2, July 2012<br />

11

Singapore companies are definitely including international directors to bring more talent and skill<br />

on board both in terms <strong>of</strong> qualification and experience. Younger international directors are being<br />

appointed who can help the board gear up to face challenges <strong>of</strong> the modern world.<br />

Board Size and Regional Diversity<br />

Table 5 shows no evident relationship between board size and regional diversity. <strong>The</strong> correlation<br />

between board size and number <strong>of</strong> countries was only 0.46. <strong>The</strong> regression equation formed was<br />

y =0.5x - 1.93 at .019 significance level<br />

Table 5: Board Size and level <strong>of</strong> Regional Diversity<br />

Board Country per Director Total<br />

Size

Corporate Governance in the Value Based Management Concept<br />

Tomasz Rojek<br />

Cracow University <strong>of</strong> Economics, Poland<br />

Keywords<br />

Corporate governance, investor relations, value based management, enterprise stakeholders, agency<br />

theory<br />

Abstract<br />

Market economies <strong>of</strong> 21st century characterize with a distinct change in the priorities <strong>of</strong> business,<br />

expressing itself in implementing by enterprises strategies focused on the multiplication <strong>of</strong> wealth <strong>of</strong> their owners, as<br />

well as the common domination <strong>of</strong> so-called investor capitalism. <strong>The</strong> consequence is the occurrence <strong>of</strong> considerable<br />

dispersion <strong>of</strong> ownership, the isolation <strong>of</strong> the ownership function from the enterprise management function and<br />

dominating enterprise ownership structures by institutional investors. In these conditions, conflicts between the<br />

interests <strong>of</strong> owners and the interests <strong>of</strong> executives managing enterprises arise. All the more that the limitation <strong>of</strong><br />

exercising control function by the first ones is increased both by the dispersion <strong>of</strong> the titles <strong>of</strong> ownership and the very<br />

character <strong>of</strong> institutional owners on behalf <strong>of</strong> which hired managers perform ownership functions. Such a conflict,<br />

defined as the “agency problem”, primarily results from the diversification <strong>of</strong> the owners’ and the managers’ goals.<br />

In this situation it was necessary to search for instruments which could effectively integrate the goals <strong>of</strong> both <strong>of</strong> these<br />

groups and thus foster enterprise development, an increase in the effectiveness <strong>of</strong> its functioning and the<br />

maximization <strong>of</strong> its market value. In such conditions, the concept <strong>of</strong> value based management was born, the systems<br />

<strong>of</strong> active corporate governance began to be created, and the process <strong>of</strong> re-including “hired” managers in the circle <strong>of</strong><br />

the enterprise owners in order to create conditions motivating them to take decisions supporting the processes <strong>of</strong> the<br />

multiplication <strong>of</strong> enterprise market value was initiated.<br />

Thus, the paper will present the essence and the characteristics <strong>of</strong> the corporate governance system, its<br />

models and assumptions, as well as elements which are convergent and divergent with the value based management<br />

concept. In particular, attention will be paid to the fact that activities focused on creating value for the owners on the<br />

one hand enable to satisfy claims <strong>of</strong> all the interested enterprise stakeholders, and on the other hand allow to create its<br />

value.<br />

Introduction<br />

An era <strong>of</strong> so-called managerial capitalism, ongoing in the world economy, characterizes, among<br />

others, with a significant separation <strong>of</strong> the ownership function from the managerial function. Due to a<br />

clash among various groups <strong>of</strong> interest in an enterprise (the owners, the managers, the employees) and<br />

external entities, a conviction has established that the main aim <strong>of</strong> an enterprise is survival and<br />

development followed by the maximization <strong>of</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>it and value. An attempt to reconcile the mentioned<br />

three groups <strong>of</strong> interest in an enterprise requires the simultaneous implementation <strong>of</strong> economic and social<br />

tasks by it. In practice, it is extremely difficult. <strong>The</strong> multitude <strong>of</strong> these tasks seriously restricts efficient<br />

enterprise management, at the same time becoming a base for endless discussions on whose interests<br />

should be realized first.<br />

Enterprises which function according to this model have problems, among others, with making<br />

plans and settling results. In consequence, they may operate not effectively enough, which may bring<br />

negative universal social consequences as it may lead to the waste <strong>of</strong> resources and the slowdown <strong>of</strong> the<br />

development <strong>of</strong> the national economy. Imposing the implementation <strong>of</strong> divergent goals on an enterprise,<br />

such as: manufacturing goals, goals connected with the multiplication <strong>of</strong> capital, educational, cultural,<br />

ecological goals, etc., is the reason for which enterprises, wanting to implement a lot <strong>of</strong> goals, in practice<br />

do not implement any <strong>of</strong> them well, and they do not implement many <strong>of</strong> them at all. Moreover, the<br />

multiplicity <strong>of</strong> goals creates serious barriers for efficient management, such as: an inability to create<br />

consistent and long-term strategic plans, blurring the effectiveness <strong>of</strong> measurement systems, and, what<br />

<strong>The</strong> Business & Management Review, Vol.2 Number 2, July 2012<br />

13

follows, it brings about difficulties in building motivation systems. <strong>The</strong> questions: whose interests should<br />

be taken into consideration in the first place and how it is possible to reconcile conflicts within this scope<br />

are always a subject <strong>of</strong> heated debates. In practice, it is the bargaining power <strong>of</strong> a specific group connected<br />

with the enterprise that decides whose interest is the most important, <strong>of</strong>ten with harm or complete<br />

disregard for the interest <strong>of</strong> other groups.<br />

<strong>The</strong> biggest problems with establishing the hierarchy <strong>of</strong> goals concern primarily medium-sized<br />

and large enterprises in which the separation <strong>of</strong> ownership and managerial functions has occurred. In<br />

smaller enterprises, where owners very <strong>of</strong>ten also deal with management, at the same time performing<br />

ownership and managerial functions, the problems occur to a smaller extent. <strong>The</strong> question <strong>of</strong> defining the<br />

basic goal for the existence <strong>of</strong> the enterprise, and the balance <strong>of</strong> power <strong>of</strong> individual groups <strong>of</strong> interest<br />

depend on a corporate governance (CG) model adopted in a given enterprise, defined as an organization<br />

<strong>of</strong> relations among the owners, the management board and the employees in the process <strong>of</strong> exercising<br />

control over the enterprise. To be more specific, it is a system <strong>of</strong> assessing activities <strong>of</strong> the enterprise<br />

management bodies in the process <strong>of</strong> its value creation and the development for stakeholders, conditioned<br />

institutionally and customarily. Stimulating development and creating enterprise value, harmonizing<br />

interests <strong>of</strong> the parties involved in it, and ensuring investment attractiveness are considered the main<br />

objectives <strong>of</strong> CG. Thus, on the one hand, it enables effective ownership control, and on the other hand it<br />

creates a mechanism which integrates the goals <strong>of</strong> individual stakeholders <strong>of</strong> the enterprise.<br />

To a great extent, the CG tasks presented above are compatible with the assumptions <strong>of</strong> the value<br />

based management concept whose general model assumes the existence <strong>of</strong> balance between diverse goals<br />

<strong>of</strong> the individual groups <strong>of</strong> interest. Value based management, by its nature focused on the maximization<br />

<strong>of</strong> this value for the owners, does not mean that building strong loyalty bonds within its framework,<br />

which fosters gaining benefits from mutual cooperation with all the other stakeholders is less important.<br />

This fact is the reason for which the value based management concept is accepted by all entities <strong>of</strong> the<br />

enterprise’s environment, and is now considered a kind <strong>of</strong> a standard <strong>of</strong> strategic management <strong>of</strong> an<br />

organization, being one <strong>of</strong> the few management philosophies which, focusing on the implementation <strong>of</strong><br />

the enterprise owners’ goals, strives at its development and conduces the improvement <strong>of</strong> effectiveness,<br />

and at the same time creates benefits for other stakeholders.<br />

<strong>The</strong> essence and the models <strong>of</strong> corporate governance<br />