- Page 2 and 3: Copyright C 2ooo by Anne Fausto-Ste

- Page 4 and 5: '"' Conrenrs Nous I lSJ Biblioaraph

- Page 6 and 7: x Preface nevertheless urge everyon

- Page 8 and 9: xii Acknowledgments have helped me

- Page 10 and 11: 2 S EXING THE B ODY Down but not ou

- Page 12 and 13: 4 S EXING THE B ODY as boys, the pr

- Page 14 and 15: 6 S EXING THE B ODY vidual body, an

- Page 16 and 17: 8 S EXING THE B ODY psychology, and

- Page 18 and 19: 10 S EXING THE B ODY ality remained

- Page 20 and 21: 12 S EXING THE B ODY Written in the

- Page 22 and 23: 14 S EXING THE B ODY and nervous il

- Page 24 and 25: 16 S EXING THE B ODY contemporary U

- Page 26 and 27: 18 S EXING THE B ODY ‘‘cultural

- Page 28 and 29: 20 S EXING THE B ODY gender—in th

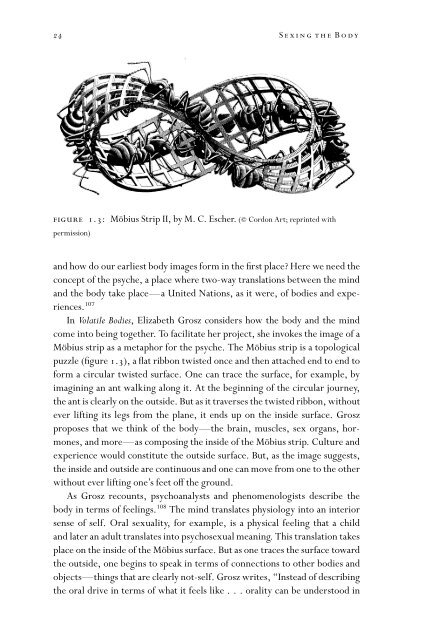

- Page 30 and 31: 22 S EXING THE B ODY structure . .

- Page 34 and 35: 26 S EXING THE B ODY How, specifica

- Page 36 and 37: 28 S EXING THE B ODY telling them t

- Page 38 and 39: 2 ‘‘THAT SEXE WHICH PREVAILETH

- Page 40 and 41: 32 S EXING THE B ODY FIGURE 2.1: Sl

- Page 42 and 43: 34 S EXING THE B ODY with interacti

- Page 44 and 45: 36 S EXING THE B ODY pate in the po

- Page 46 and 47: 38 S EXING THE B ODY Pseudohermaphr

- Page 48 and 49: 40 S EXING THE B ODY were demanding

- Page 50 and 51: 42 S EXING THE B ODY on the gonads

- Page 52 and 53: 44 S EXING THE B ODY Although less

- Page 54 and 55: 46 S EXING THE B ODY that ‘‘whi

- Page 56 and 57: 48 S EXING THE B ODY Luckily for th

- Page 58 and 59: 50 S EXING THE B ODY FIGURE 3.3: Th

- Page 60 and 61: 52 TABLE 3.1 Some Common Types of I

- Page 62 and 63: 54 S EXING THE B ODY varies widely

- Page 64 and 65: 56 S EXING THE B ODY seventy-five h

- Page 66 and 67: 58 S EXING THE B ODY surgery should

- Page 68 and 69: 60 S EXING THE B ODY TABLE 3.3 Rece

- Page 70 and 71: 62 S EXING THE B ODY FIGURE 3.6: Re

- Page 72 and 73: 64 S EXING THE B ODY their child’

- Page 74 and 75: 66 S EXING THE B ODY dren.’’ An

- Page 76 and 77: 68 S EXING THE B ODY Models of Psyc

- Page 78 and 79: 70 S EXING THE B ODY psychiatrists

- Page 80 and 81: 72 S EXING THE B ODY as one histori

- Page 82 and 83:

74 S EXING THE B ODY how intersexua

- Page 84 and 85:

76 S EXING THE B ODY sized penises

- Page 86 and 87:

4 SHOULD THERE BE ONLY TWO SEXES x

- Page 88 and 89:

80 S EXING THE B ODY implausible is

- Page 90 and 91:

TABLE 4.1 Outcomes of Reduction Cli

- Page 92 and 93:

84 S EXING THE B ODY patients and w

- Page 94 and 95:

86 S EXING THE B ODY goal. 37 In ou

- Page 96 and 97:

TABLE 4.2 Evaluation of Vaginoplast

- Page 98 and 99:

TABLE 4.2 (Continued) 90 # OF AGE A

- Page 100 and 101:

92 S EXING THE B ODY The Right To R

- Page 102 and 103:

94 S EXING THE B ODY FIGURE 4.1: Fr

- Page 104 and 105:

TABLE 4.3 Psychological Outcomes of

- Page 106 and 107:

TABLE 4.3 (Continued) DEVELOPMENTAL

- Page 108 and 109:

TABLE 4.3 (Continued) 100 DEVELOPME

- Page 110 and 111:

TABLE 4.4 Psychological Outcomes of

- Page 112 and 113:

TABLE 4.4 (Continued) 104 DEVELOPME

- Page 114 and 115:

TABLE 4.4 (Continued) 106 DEVELOPME

- Page 116 and 117:

108 S EXING THE B ODY tions and eve

- Page 118 and 119:

110 S EXING THE B ODY Toward the En

- Page 120 and 121:

112 S EXING THE B ODY and a woman,

- Page 122 and 123:

114 S EXING THE B ODY and methods.

- Page 124 and 125:

116 S EXING THE B ODY taken from ou

- Page 126 and 127:

118 S EXING THE B ODY At first ever

- Page 128 and 129:

120 S EXING THE B ODY TABLE 5.1 Nin

- Page 130 and 131:

122 S EXING THE B ODY anatomical la

- Page 132 and 133:

124 S EXING THE B ODY Mall engaged

- Page 134 and 135:

126 S EXING THE B ODY FIGURE 5.3: A

- Page 136 and 137:

TABLE 5.3 Absolute Sex Differences

- Page 138 and 139:

130 S EXING THE B ODY Genu Isthmus

- Page 140 and 141:

TABLE 5.4 Relative Sex Differences

- Page 142 and 143:

TABLE 5.5 Hand Preference, Sex, and

- Page 144 and 145:

136 S EXING THE B ODY law-abiding a

- Page 146 and 147:

138 S EXING THE B ODY they would us

- Page 148 and 149:

140 S EXING THE B ODY Well, 66 perc

- Page 150 and 151:

142 S EXING THE B ODY GENDER DIFFER

- Page 152 and 153:

GENDER DIFFERENCES GENDER DIFFERENC

- Page 154 and 155:

6 SEX GLANDS, HORMONES, AND GENDER

- Page 156 and 157:

148 S EXING THE B ODY Scientists di

- Page 158 and 159:

150 S EXING THE B ODY FIGURE 6.1: B

- Page 160 and 161:

152 TABLE 6.1 Thinking About Sex an

- Page 162 and 163:

154 S EXING THE B ODY plasms differ

- Page 164 and 165:

156 S EXING THE B ODY he considered

- Page 166 and 167:

158 S EXING THE B ODY much of the e

- Page 168 and 169:

TABLE 6.2 Steinach’s Experiments

- Page 170 and 171:

162 S EXING THE B ODY stronger than

- Page 172 and 173:

164 S EXING THE B ODY The naturally

- Page 174 and 175:

TABLE 6.3 Moore’s Transplantation

- Page 176 and 177:

168 S EXING THE B ODY less certain

- Page 178 and 179:

7 DO SEX HORMONES REALLY EXIST (GEN

- Page 180 and 181:

172 S EXING THE B ODY The early twe

- Page 182 and 183:

174 S EXING THE B ODY became Superi

- Page 184 and 185:

176 S EXING THE B ODY women’s rig

- Page 186 and 187:

178 S EXING THE B ODY In 1939 CRPS

- Page 188 and 189:

180 S EXING THE B ODY FIGURE 7.3: P

- Page 190 and 191:

182 S EXING THE B ODY mones came in

- Page 192 and 193:

184 S EXING THE B ODY sugar, the fe

- Page 194 and 195:

186 S EXING THE B ODY the role of s

- Page 196 and 197:

188 S EXING THE B ODY FIGURE 7.5: N

- Page 198 and 199:

190 S EXING THE B ODY which denoted

- Page 200 and 201:

192 S EXING THE B ODY the very thin

- Page 202 and 203:

194 S EXING THE B ODY steroids as o

- Page 204 and 205:

196 S EXING THE B ODY consolidated

- Page 206 and 207:

198 S EXING THE B ODY Sexual chaos

- Page 208 and 209:

200 S EXING THE B ODY omy in rabbit

- Page 210 and 211:

202 S EXING THE B ODY had no ovarie

- Page 212 and 213:

204 S EXING THE B ODY equated with

- Page 214 and 215:

206 S EXING THE B ODY measure hormo

- Page 216 and 217:

208 S EXING THE B ODY ‘‘environ

- Page 218 and 219:

210 S EXING THE B ODY FIGURE 8.2: B

- Page 220 and 221:

212 S EXING THE B ODY Young, who ob

- Page 222 and 223:

214 S EXING THE B ODY for anatomica

- Page 224 and 225:

216 S EXING THE B ODY activators. T

- Page 226 and 227:

218 S EXING THE B ODY and female ro

- Page 228 and 229:

220 S EXING THE B ODY Many of them

- Page 230 and 231:

222 S EXING THE B ODY androgen on t

- Page 232 and 233:

224 S EXING THE B ODY While Beach

- Page 234 and 235:

226 S EXING THE B ODY 1920s, by the

- Page 236 and 237:

228 S EXING THE B ODY FIGURE 8.6: A

- Page 238 and 239:

230 S EXING THE B ODY females, and

- Page 240 and 241:

232 S EXING THE B ODY ‘wiring’

- Page 242 and 243:

FIGURE 9.1: A budding scientist (So

- Page 244 and 245:

236 S EXING THE B ODY DNA needed an

- Page 246 and 247:

238 S EXING THE B ODY FIGURE 9.2: S

- Page 248 and 249:

240 S EXING THE B ODY In other word

- Page 250 and 251:

242 S EXING THE B ODY ponents and n

- Page 252 and 253:

244 S EXING THE B ODY others to ‘

- Page 254 and 255:

246 S EXING THE B ODY with other hu

- Page 256 and 257:

248 S EXING THE B ODY popped into m

- Page 258 and 259:

250 S EXING THE B ODY gender can mo

- Page 260 and 261:

252 S EXING THE B ODY with another

- Page 262 and 263:

254 S EXING THE B ODY FIGURE 9.4: T

- Page 264 and 265:

notes Chapter 1: Dueling Dualisms 1

- Page 266 and 267:

Notes 259 (and are) suspicious of g

- Page 268 and 269:

Notes 261 a veil that he refers to

- Page 270 and 271:

Notes 263 22 percent of women repor

- Page 272 and 273:

Notes 265 in previous historical er

- Page 274 and 275:

Notes 267 account of the history of

- Page 276 and 277:

Notes 269 93. Stein 1998. For a ful

- Page 278 and 279:

Notes 271 note that this approach t

- Page 280 and 281:

Notes 273 important. They urge caut

- Page 282 and 283:

Notes 275 26. Dreger 1998b. 27. Quo

- Page 284 and 285:

Notes 277 tailed yet accessible boo

- Page 286 and 287:

Notes 279 B. In females 1.Absence o

- Page 288 and 289:

Notes 281 36. Mercado et al. 1995.

- Page 290 and 291:

Notes 283 cluding that which we ter

- Page 292 and 293:

Notes 285 98. Money and Ehrhardt 19

- Page 294 and 295:

Notes 287 system. As I discuss in t

- Page 296 and 297:

Notes 289 masculine behavior’’

- Page 298 and 299:

Notes 291 Berenbaum and Hines’s m

- Page 300 and 301:

Notes 293 ‘‘early hormone expos

- Page 302 and 303:

Notes 295 injection is not discusse

- Page 304 and 305:

Notes 297 Three of the twelve appar

- Page 306 and 307:

Notes 299 Holmes chose to go public

- Page 308 and 309:

Notes 301 operation, refers to ‘

- Page 310 and 311:

Notes 303 51. Slijper et al. 1998,p

- Page 312 and 313:

Notes 305 68. Actually, this moment

- Page 314 and 315:

Notes 307 99. See de la Chapelle 19

- Page 316 and 317:

Notes 309 antilocalizers cheered th

- Page 318 and 319:

Notes 311 38. In1999 it is the sple

- Page 320 and 321:

Notes 313 popular PET scans are con

- Page 322 and 323:

Notes 315 64. Halpern (1998), p. 33

- Page 324 and 325:

Notes 317 France and England as the

- Page 326 and 327:

Notes 319 removed from that of Amer

- Page 328 and 329:

Notes 321 zie, Rule’s Q is most p

- Page 330 and 331:

Notes 323 evolution of brain asymme

- Page 332 and 333:

Notes 325 nature/nurture dichotomy

- Page 334 and 335:

Notes 327 literature on social worl

- Page 336 and 337:

Notes 329 driving force in many agi

- Page 338 and 339:

Notes 331 a story of quackery. Nor,

- Page 340 and 341:

Notes 333 came Dean of Biological S

- Page 342 and 343:

Notes 335 human biology, with virtu

- Page 344 and 345:

Notes 337 sion of Medical Sciences.

- Page 346 and 347:

Notes 339 mal, while all other form

- Page 348 and 349:

Notes 341 59. Frank and Goldberger

- Page 350 and 351:

Notes 343 93. While most readers ar

- Page 352 and 353:

Notes 345 15. Schlesinger 1958, p.6

- Page 354 and 355:

Notes 347 kind of struggle against

- Page 356 and 357:

Notes 349 ever, that in mice neithe

- Page 358 and 359:

Notes 351 Beach’s work and manner

- Page 360 and 361:

Notes 353 the majority of the femal

- Page 362 and 363:

Notes 355 ability to substitute for

- Page 364 and 365:

Notes 357 Here I discuss only matin

- Page 366 and 367:

Notes 359 heat . . . duration of ma

- Page 368 and 369:

Notes 361 In addition to attacking

- Page 370 and 371:

Notes 363 127. Clark 1993b, p. 37.

- Page 372 and 373:

Notes 365 the altered testosterone

- Page 374 and 375:

Notes 367 treatment (van de Poll et

- Page 376 and 377:

Notes 369 to understanding relation

- Page 378 and 379:

Notes 371 the brain—a region of t

- Page 380 and 381:

Notes 373 neuromuscular development

- Page 382 and 383:

Notes 375 der prophecies based on s

- Page 384 and 385:

Notes 377 to present-day studies on

- Page 386 and 387:

Notes 379 ties. Taylor, however, re

- Page 388 and 389:

382 Bibliography Abu-Arafeh, W., B.

- Page 390 and 391:

384 Bibliography Azziz, R., R. Mula

- Page 392 and 393:

386 Bibliography ———. 1968. T

- Page 394 and 395:

388 Bibliography Berenson, A., A. H

- Page 396 and 397:

390 Bibliography Breines, W. 1992.

- Page 398 and 399:

392 Bibliography ———. 1999. R

- Page 400 and 401:

394 Bibliography Corner, G. W. 1964

- Page 402 and 403:

396 Bibliography Deanesly, R., and

- Page 404 and 405:

398 Bibliography Dorsey, G. A. 1925

- Page 406 and 407:

400 Bibliography Elias, S., and G.

- Page 408 and 409:

402 Bibliography ally dimorphic beh

- Page 410 and 411:

404 Bibliography on its purificatio

- Page 412 and 413:

406 Bibliography development: A dev

- Page 414 and 415:

408 Bibliography Gustavson, R. G. 1

- Page 416 and 417:

410 Bibliography Hansen, B. 1989. A

- Page 418 and 419:

412 Bibliography Hill, R. T. 1937a.

- Page 420 and 421:

414 Bibliography mission of active

- Page 422 and 423:

416 Bibliography Jost, A., and Y. B

- Page 424 and 425:

418 Bibliography Klein, M., and A.

- Page 426 and 427:

420 Bibliography olution. In Discou

- Page 428 and 429:

422 Bibliography Lott, B., and D. M

- Page 430 and 431:

424 Bibliography Martin, J. B. 1993

- Page 432 and 433:

426 Bibliography ———. 1956. S

- Page 434 and 435:

428 Bibliography ual Differentiatio

- Page 436 and 437:

430 Bibliography Oppenheim, J. S.,

- Page 438 and 439:

432 Bibliography Phoenix, C. 1978.

- Page 440 and 441:

434 Bibliography Reilly, J. M., and

- Page 442 and 443:

436 Bibliography Russett, C. E. 198

- Page 444 and 445:

438 Bibliography Simpson, J. L. 198

- Page 446 and 447:

440 Bibliography ———. 1913. P

- Page 448 and 449:

442 Bibliography feminist perspecti

- Page 450 and 451:

444 Bibliography Van den Wijngaard,

- Page 452 and 453:

446 Bibliography Werner, M. H., J.

- Page 454 and 455:

448 Bibliography gic modulation of

- Page 456 and 457:

452 Index Moore cited by, 353(n65)

- Page 458 and 459:

454 Index clitoral recession, 60(ta

- Page 460 and 461:

456 Index Earhart, Amelia, 192 Eder

- Page 462 and 463:

458 Index Money and Ehrhardt’s de

- Page 464 and 465:

460 Index Hausman, Bernice, 23 Hawk

- Page 466 and 467:

462 Index clinical features, 52(tab

- Page 468 and 469:

464 Index Lichtenstern, R., 163, 33

- Page 470 and 471:

466 Index Nerve cells. See Brain; C

- Page 472 and 473:

468 Index sexual preference in, 225

- Page 474 and 475:

470 Index Young’s research/theori

- Page 476 and 477:

472 Index Uecker, A., 324(n104) Und