Download - Museum of Contemporary Art

Download - Museum of Contemporary Art

Download - Museum of Contemporary Art

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Introduction to this resource<br />

This resource is designed to introduce teachers and students to the MCA exhibition In the Balance: <strong>Art</strong> for a Changing World, 21 August – 31 October<br />

2010. It provides an overview <strong>of</strong> the themes <strong>of</strong> the exhibition, and pr<strong>of</strong>iles seven <strong>of</strong> the exhibiting artists. In each artist’s pr<strong>of</strong>ile, you will find quotes<br />

from the artist, biographical information and a description <strong>of</strong> their work on exhibition at the MCA. At the end <strong>of</strong> each artist’s pr<strong>of</strong>ile, points for<br />

discussion and focus questions are provided under the heading Thinking About it and art making activities are suggested under the heading Making<br />

it. A glossary and list <strong>of</strong> references are included to assist with further research; glossary terms appear in bold throughout the text and can be found at<br />

the end <strong>of</strong> the document.<br />

A catalogue is available for this exhibition from the MCA Store, and may be used in conjunction with the In the Balance: <strong>Art</strong> for a<br />

Changing World education resource. Visit the MCA website for full details <strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong>fsite events and programs, www.mca.com.au<br />

Contents<br />

Introduction to this resource<br />

Curriculum Connections<br />

Themes in the exhibition<br />

<strong>Art</strong>ist Pr<strong>of</strong>iles<br />

• Badger Bates<br />

• Lauren Berkowitz<br />

• Diego Bonetto<br />

• Nici Cumpston<br />

• Janet Laurence<br />

• James Newitt<br />

• Jeanne van Heeswijk<br />

Glossary<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

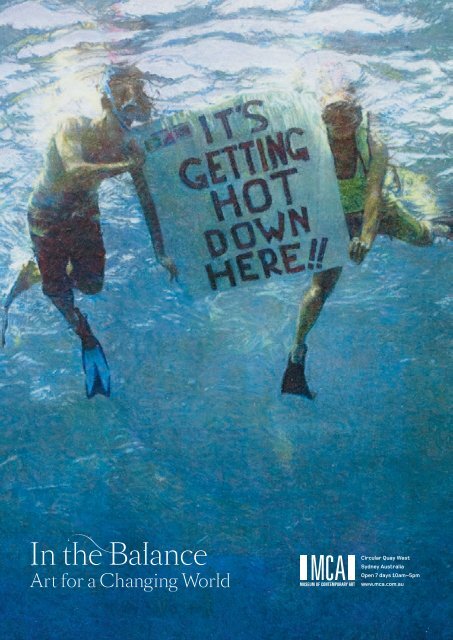

Cover:<br />

Andrea Bowers<br />

Step It Up Activist, Sand Key Reef, Key West, Florida<br />

Part <strong>of</strong> North America’s Only Remaining Coral Barrier Reef (detail) 2009<br />

coloured pencil on paper<br />

56.52 x 76.2 cm<br />

Courtesy the artist and Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York and Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects<br />

Image courtesy the artist, Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York and Suzanne Vielmetter Los Angeles<br />

Projects © the artist<br />

2

Curriculum Connections<br />

In the Balance: <strong>Art</strong> for a Changing World provides students with the opportunity to undertake cross-disciplinary study through the<br />

artworks on exhibition. Below are a list <strong>of</strong> key curriculum areas for each learning stage and some suggestions on appropriate content.<br />

Early Stage 1 – Stage 3 (K-Year 6)<br />

Creative <strong>Art</strong>s<br />

English<br />

HSIE<br />

Science and Technology<br />

Stage 4 & 5 (Year 7 - 10)<br />

Aboriginal Studies<br />

Australian Geography<br />

Design and Technology<br />

English<br />

Photographic & Digital Media<br />

Science<br />

Visual <strong>Art</strong>s<br />

Visual Design<br />

Stage 6 (Year 11 – 12)<br />

Aboriginal Studies<br />

Biology<br />

English<br />

Earth and Environmental Science<br />

Geography<br />

Photography, Video & Digital Imaging<br />

Society and Culture<br />

Visual <strong>Art</strong>s<br />

Visual Design<br />

ESL/NESB/CALD<br />

Developing a visual arts vocabulary<br />

Oral and written responses<br />

Cultural identity and other issues in the visual arts<br />

3

Themes in the exhibition<br />

In the Balance: <strong>Art</strong> for a Changing World presents a variety <strong>of</strong> works by Australian and selected international artists who respond to contemporary<br />

ecological issues in their art practice. This major exhibition is distinctive in its curatorial approach to the subject <strong>of</strong> the environment, as it not only<br />

reflects the diversity <strong>of</strong> environmental concerns prevailing both within and beyond Australia today, but it also showcases the many different ways<br />

in which contemporary artists are responding to these issues. Importantly, the works selected for this exhibition are not simply engaging with the<br />

landscape, or responding aesthetically to nature, but are made by artists who denote a more ‘political imperative’ in their practice.<br />

The exhibition encompasses a variety <strong>of</strong> media, including sculpture, installation, print making, photography, film and video. In the Balance also<br />

features a number <strong>of</strong> site-specific and commissioned works, performances and projects, many <strong>of</strong> which extend their reach beyond the MCA galleries<br />

and spill over into a wide range <strong>of</strong> public realms, including the MCA front lawn, publicly accessible areas <strong>of</strong> the central business district, urban<br />

precincts within Greater Sydney, and even virtual community environs like Facebook.<br />

Listed below are some <strong>of</strong> the key environmental themes and issues that are explored within the exhibition:<br />

• Landscape<br />

• Sustainability<br />

• Waste and recycling<br />

• Community engagement<br />

• Urban regeneration<br />

• Participatory practices<br />

• Water conservation<br />

• Indigenous approaches to conservation and natural resources<br />

• Clean energy; fossil fuels and their alternatives<br />

• Environmental politics<br />

The following sections will explore some <strong>of</strong> these themes in greater detail in relation to the work <strong>of</strong> seven key artists <strong>of</strong> the nearly 40 featured in<br />

In the Balance: <strong>Art</strong> for a Changing World. These artists are;<br />

• Badger Bates<br />

• Lauren Berkowitz<br />

• Diego Bonetto<br />

• Nici Cumpston<br />

• Janet Laurence<br />

• James Newitt<br />

• Jeanne van Heeswijk<br />

4

Badger Bates<br />

Badger Bates Mission Mob and Bend Mob 1950s (detail) 2009<br />

linocut print 57.5 x 90.5 cm (sheet) <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Contemporary</strong> <strong>Art</strong>, purchased with funds provided by the Coe and Mordant families,<br />

2009<br />

Image courtesy and © the artist<br />

5

Badger Bates<br />

We did that (traditional art practice) then, but today now, we’re into recycling. White people and black people go pick up rubbish over there; they<br />

(white people) will make art work and they’ll call it waste art or something. And our two races, you know, Aboriginal and European, we are doing the<br />

same thing, but we don’t realise it. We are doing the same thing by picking up junk over here and making something over here, but none <strong>of</strong> us realise<br />

we’re doing the same thing, but we are! 1 Badger Bates, 2010<br />

Born 1947, Darling River, Wilcannia, New South Wales. Lives and Works Wilcannia, New South Wales.<br />

People: Barkindji; Language: Barkindji 2<br />

William Brian (Badger) Bates was born on the Darling River at Wilcannia in 1947, and is <strong>of</strong> both Aboriginal and European descent. As a child, Badger<br />

was raised by his mother’s extended family and his grandmother, Granny Moysey, a well-known and knowledgeable Barkindji matriarch who spoke<br />

several Aboriginal languages. Throughout his childhood, Badger travelled the country with his grandmother, learning the language, history and<br />

culture <strong>of</strong> various Barkindji groups, and from a young age was taught how to carve traditional designs onto emu eggs and wooden artefacts. 3 Many<br />

years later, Badger would encounter similar designs in the rock engravings and paintings at the Mutawintji National Park, and in wooden artefacts<br />

at the Australian <strong>Museum</strong> in Sydney – ‘I just felt proud in my mind [that] I knew it through what Granny taught me’. 4 Now an Elder <strong>of</strong> the Barkindji<br />

people and a highly influential cultural broker, Badger is an authoritative figure on the subject <strong>of</strong> identity, culture and stories <strong>of</strong> the land through<br />

specific Barkindji designs. His artistic practice is diverse, ranging from sculpture, metalwork and printmaking to carved works in wood, stone, shell and<br />

emu eggs, and embodies a distinctive blend <strong>of</strong> traditional, historical and contemporary cultural conventions. He was also the Senior Archaeological<br />

Officer for the National Parks and Wildlife Service in Broken Hill for over twenty years, before retiring in 2005.<br />

The degradation <strong>of</strong> the Darling River, or Paaka, in western NSW, and the effects <strong>of</strong> drought, erosion and pollution are issues <strong>of</strong> great concern to<br />

Badger. The three linocut prints featured in this exhibition each tell an intricate story pertaining to important cultural sites and the artist’s own<br />

lived history and deeply personal connections to the Paaka. Mission Mob and Bend Mob, Wilcannia 1950s (2009) represents both a geographically<br />

accurate and culturally specific topography <strong>of</strong> the river landscape near Wilcannia, consistent with Badger’s upbringing from the 1950s. Whilst the<br />

colonial aspects <strong>of</strong> the landscape, such as the mission houses, the school and demarcated roads carry immense historical references in themselves,<br />

both on a personal and national level, they also serve as a stark and rigid linear contrast to the flowing lines <strong>of</strong> the river and organic motifs <strong>of</strong> the<br />

trees and creeks. The impact <strong>of</strong> colonisation on the landscape can also be seen in the wavering lines that delineate the opposite side <strong>of</strong> the riverbank,<br />

which Badger includes here as a reminder <strong>of</strong> the considerable effects that pastoral activities have had on the erosion <strong>of</strong> the land and the silting <strong>of</strong> the<br />

MacIntyre River<br />

river water.<br />

Paroo River<br />

Warrego River<br />

Culgoa River<br />

Boggabilla<br />

Toomelah<br />

Bourke<br />

Broken Hill<br />

Wilcannia<br />

Darling River<br />

NSW<br />

SA<br />

Lachlan River<br />

Lake Bonney<br />

Cowra<br />

Sydney<br />

Adelaide<br />

Mildura<br />

Hay<br />

Murrumbidgee River<br />

Wagga Wagga<br />

VIC<br />

Murray River<br />

Albury<br />

Map <strong>of</strong> Darling River and Wilcannia,<br />

New South Wales<br />

1 Author’s interview with the <strong>Art</strong>ist, July 2010<br />

2 Sometimes also referred to as Paarkindji or Paarkantji<br />

3 Lorraine Gibson, ‘’We don’t do dots – ours is lines’ – Asserting a Barkindji Style, Oceania, vol. 78, 2008, p.285<br />

4 ibid, p.285<br />

6

Badger Bates<br />

Iron Pole Bend, Darling River, Wilcannia 2007<br />

linocut print<br />

42.5 x 56 cm (sheet)<br />

<strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Contemporary</strong> <strong>Art</strong>, purchased with funds provided by the Coe and Mordant families, 2009<br />

Image courtesy and © the artist<br />

The bend in the river at the lower right-hand corner <strong>of</strong> Mission Mob and Bend Mob 1950s is depicted again in greater detail in the work, Iron Pole<br />

Bend, Darling River, Wilcannia (2007). This work directly illustrates different aspects <strong>of</strong> environmental changes in the area, such as the need for water<br />

and rain, along with the area’s natural inhabitants. On the left-hand side <strong>of</strong> the print, the skeletons <strong>of</strong> dead fish indicate the dry conditions <strong>of</strong> Lake<br />

Wytuycka, which hasn’t had water for a long time, and the body lines <strong>of</strong> the two Ngatyi (Rainbow Serpents) represent the serpent’s underground<br />

thoroughfare from one river bend to another (the end-points <strong>of</strong> which are indicated by the two Ngatyi depicted in Mission Mob and Bend Mob<br />

1950s). 5 The stories contained within these works not only articulate a deeply felt connection to the landscape; they also reflect a continuing<br />

relationship that we all share with the nature and culture <strong>of</strong> our land. Through his art, Badger continues on his path as the Paaka’s authorial voice<br />

and environmental guardian to inform and inspire an ever-expanding audience.<br />

5 Author’s interview with the <strong>Art</strong>ist, July 2010<br />

7

PRIMARY<br />

Thinking about it<br />

(K-2)<br />

Take a close look at Badger’s picture <strong>of</strong> Iron Pole bend, Darling River,<br />

Wilcannia. How many animals can you see Can you name all <strong>of</strong> the<br />

animals Out <strong>of</strong> these animals, which ones need water in order to<br />

survive<br />

(3-6)<br />

What effects can drought and erosion have on the landscape How<br />

does this affect the animals that live on the land and in the lakes<br />

and rivers Badger tells a story <strong>of</strong> an Irish friend and neighbour from<br />

Wilcannia who likes goats. Badger has hidden an image <strong>of</strong> a goat in his<br />

linocut print Mission Mob and Bend Mob, Wilcannia 1950s. Can you find<br />

it (Hint: you may have to turn your head sideways!)<br />

Making it<br />

Using white pencils on black paper, draw a picture <strong>of</strong> your street or<br />

school from an aerial or ‘bird’s eye’ view. Try using different kinds<br />

<strong>of</strong> lines – wavy, straight, thick, thin, dotted or dashed – to represent<br />

different things like roads, nearby water or tracks that you might walk or<br />

ride along. You might also like to include a key or legend to identify the<br />

patterns or symbols you use.<br />

Two <strong>of</strong> Badger’s prints tell the sky story <strong>of</strong> the Kaalthi (Emu) in the Milky<br />

Way. The Barkindji people know whether the emu is laying eggs just by<br />

reading the constellations in the stars – ‘when the emu’s head sticks<br />

straight up, that means it’s not laying, but when the emu’s head drops<br />

down, that means it’s trying to hide itself when it sits on the nest’. 6<br />

Create a short story based on the emu in the work Emu Sky (2008).<br />

What happens when the emu eggs hatch<br />

SECONDARY<br />

Thinking about it<br />

(7-9)<br />

The main road depicted in Mission Mob and Bend Mob, Wilcannia 1950s<br />

(2009) ‘represents the road that many Aboriginal children were taken<br />

away on by the Aboriginal Protection Board, which some returned on<br />

years later, and symbolically, the path for those still trying to find their<br />

way home’. 7 Research the history <strong>of</strong> Australia’s Stolen Generation. How<br />

does this affect the way you interpret Badger’s visual depiction <strong>of</strong> his<br />

childhood memories<br />

(10-12)<br />

Think about the different methods and tools that are required for<br />

carving into stone, wood, linoleum and emu eggs. How does this affect<br />

your understanding <strong>of</strong> Badger’s practice<br />

The practice <strong>of</strong> printmaking revolves around the design <strong>of</strong> positive and<br />

negative space. How do you think Badger’s childhood knowledge <strong>of</strong><br />

carving and his subsequent sculptural practice as an artist might have<br />

influenced his development into printmaking<br />

Making it<br />

Use your knowledge <strong>of</strong> your local environment as the basis for a body<br />

<strong>of</strong> work in lino. Collect photos and maps as both a visual reference and<br />

source <strong>of</strong> material. Use a computer-editing program, such as Adobe<br />

Photoshop, Gimp or Google SketchUp or to adjust the contrast on your<br />

design before transferring it to lino.<br />

Badger utilises lino printing in his practice which is primarily the removal<br />

<strong>of</strong> negative space from the lino tile and a print <strong>of</strong> the positive space that<br />

remains. Explore other forms <strong>of</strong> printmaking to document your personal<br />

history. Experiment with the process <strong>of</strong> monoprinting and collography,<br />

which is the opposite process to lino, where you build up the printed<br />

surface, rather than remove it as a relief process. How will your choice<br />

<strong>of</strong> materials and process reflect your conceptual ideas<br />

6 Author’s interview with the <strong>Art</strong>ist, July 2010<br />

7 Keith Munro, ‘Badger Bates’, In the Balance: <strong>Art</strong> for a Changing World, exhibition<br />

catalogue, <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Contemporary</strong> <strong>Art</strong>, Sydney, 2010, p.26<br />

8

Lauren Berkowitz<br />

Lauren Berkowitz<br />

Bags 1994 (remade 2010) (detail)<br />

plastic dimensions variable<br />

Installation view, National Gallery <strong>of</strong> Australia, Canberra<br />

Image courtesy and © the artist<br />

9

Lauren Berkowitz<br />

Born 1965, Melbourne, Victoria. Lives and Works Melbourne, Victoria.<br />

The work [Sustenance (2010)] incorporates indigenous plants that are adaptable and suited to our harsh climate, as well as introduced species that<br />

must be nurtured, watered and controlled, and [that in the] long-term are not sustainable; as our weather becomes more extreme, also included are<br />

cactus plants that are self-sustaining in climatically harsh conditions. 8 Lauren Berkowitz, 2010<br />

Lauren Berkowitz is a prominent Melbourne-based installation artist, primarily concerned with creating ephemeral and site-specific works made<br />

produced various recycled materials. Since the early 1990s, Berkowitz has accumulated and utilised a range <strong>of</strong> objects from nature and everyday<br />

modern living to create sculptures and installations intended for gallery exhibition, museum displays and public spaces. Her works are <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

temporal, or constructed only for the duration <strong>of</strong> their display, and are composed <strong>of</strong> consumer waste materials and botanical detritus either<br />

associated with, or collected within, the immediate locality in which they are displayed.<br />

For Berkowitz, the ever-changing modern-day landscape is both a source <strong>of</strong> inspiration and a resource for her art-making. Collecting<br />

is an important aspect <strong>of</strong> her practice and each individual work represents the fruits <strong>of</strong> extensive labour and research. By collating,<br />

assembling and re-arranging a combination <strong>of</strong> found objects, both natural and<br />

human-made, the artist not only participates in an active engagement with the world<br />

around us, but also instigates an ecological imperative in her art making practice,<br />

transforming proverbial environmental issues into tangible acts <strong>of</strong> regeneration.<br />

For this exhibition, Berkowitz delivers her distinctively ecological take on site-specificity and<br />

the wastage perpetuated by humanity. Bags (1994/2010), is an expanded reconstruction <strong>of</strong> a<br />

previous sculptural installation, made again expressly for display in the MCA galleries. For this<br />

piece, Berkowitz enlisted the help <strong>of</strong> volunteers, including MCA staff, to collect the 3000 recycled<br />

plastic shopping bags required to realise the installation. Attached to two parallel frameworks <strong>of</strong><br />

netting, and suspended mid-gallery space to create a gigantic aerated corridor, this work invites<br />

viewers to pass through a vast wall <strong>of</strong> discarded waste and physically comprehend the enormity <strong>of</strong><br />

the environmental consequence to our collective everyday actions. Minimalist in its approach and<br />

recyclable in its aesthetic 9 , the work’s temporality forces us to realise that, at the conclusion <strong>of</strong><br />

the exhibition, these temporarily re-valued objects <strong>of</strong> beauty are destined to rejoin the (re)cycle <strong>of</strong><br />

our mass-produced plastic consumables.<br />

Sustenance (2010) is a new installation project commissioned by the MCA specifically for this<br />

exhibition. The project began many months ago, with Berkowitz undertaking extensive research<br />

into the edible and medicinal qualities <strong>of</strong> various indigenous plants, succulents, and European<br />

and Asian herbs and vegetables found in New South Wales. 10 The artist then recruited a number<br />

<strong>of</strong> school students, community groups and green-thumbed individuals to assist in growing a<br />

collection <strong>of</strong> potted plants. In total, the artist presents 650 plants, with 300 on exhibition at any<br />

one time. What we see in the galleries is at once the material realisation <strong>of</strong> the project in the<br />

gallery space, both inside and out, and the ongoing cultivation <strong>of</strong> the plants as living organisms.<br />

Assembled along a low table made from recycled timber, and rotated on a regular basis from the<br />

Above, from top to botom:<br />

Plants being grown in preparation for Sustenance (detail),<br />

2010<br />

The Erskineville Community Garden, 52-54 Erskineville Rd,<br />

Erskineville.<br />

MCA Level 3 terrace, these miscellaneous specimens have been replanted into provisional pots generated from recycled plastic bottles and containers.<br />

Drawing inspiration from an ever-maturing environmental consciousness and exploring the artistic potential <strong>of</strong> cultural sustainability, Berkowitz’<br />

installations resonate meaningfully within a contemporary landscape <strong>of</strong> change and complexity. After the closure <strong>of</strong> the exhibition, the plants<br />

included in Sustenance will be given back to the growers, schools and community members who nurtured them in preparation for the exhibition.<br />

8 Lauren Berkowitz cited in Rachel Kent, ‘Lauren Berkowitz’, In the Balance: <strong>Art</strong> for a Changing World, <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Contemporary</strong> <strong>Art</strong>, Sydney, 2010, p.30<br />

9 Ibid.<br />

10 Ibid<br />

10

PRIMARY<br />

Thinking about it<br />

(K-2)<br />

Firstly, look at Lauren’s Bags installation from far away – what does it<br />

look like What do you imagine it would feel like As you move closer,<br />

what do you notice When you walk through the artwork’s corridor,<br />

listen carefully to the sounds made by the walls as you pass by them.<br />

Are the walls moving, or do you think they might be breathing What<br />

else might they be doing (i.e., shivering, shaking)<br />

(3-6)<br />

What plants do you have in your garden at home or at school Can<br />

you find them on Lauren’s table Why do you think Lauren chose only<br />

to include plants found in New South Wales In pairs or in groups,<br />

brainstorm what you think the artist should do with the plants after the<br />

exhibition finishes.<br />

Making it<br />

Start a collection in your class <strong>of</strong> plastic recyclable materials. Think<br />

about what kind <strong>of</strong> materials you want to work with – bags, bottles,<br />

coloured or clear, etc – and how many. Once your collection target is<br />

reached, use these collected items to create a sculptural artwork, in<br />

either pairs, small groups or as a class.<br />

Create a ‘plant exchange’ at your school. Encourage everyone in your<br />

class to bring in a cutting <strong>of</strong> a plant from home potted in a recycled<br />

milk carton. Be sure to record the name <strong>of</strong> the plant and the care<br />

instructions for encouraging growth. Organise a swap meet with your<br />

class and see the different varieties <strong>of</strong> local flora thrive. Choose one<br />

<strong>of</strong> the plants featured on Lauren’s gallery installation table. Complete<br />

a drawing <strong>of</strong> this plant, capturing its colours and different textures –<br />

don’t forget its unique recycled ‘bottle pot’! Find out the name <strong>of</strong> this<br />

plant and research a few <strong>of</strong> its interesting facts. Present your findings<br />

and drawing on a poster to hang on the wall so that others may learn<br />

about your chosen plant.<br />

SECONDARY<br />

Thinking about it<br />

(7-9)<br />

What is a “commissioned” art work Why would an institution, like<br />

the MCA, invite an artist to make a work specifically for an exhibition<br />

What aspects <strong>of</strong> Lauren Berkowitz’s project Sustenance have/will take<br />

place outside <strong>of</strong> the exhibition Why do you think this is important in<br />

terms <strong>of</strong> understanding the artist’s intentions<br />

(10-12)<br />

Think about the different ways in which Lauren Berkowitz’s artistic<br />

processes and material choices reflect her conceptual practice. In pairs<br />

or groups, examine the <strong>Art</strong>ist’s relationship with the other agencies<br />

<strong>of</strong> the artworld (the <strong>Art</strong>work, Audience and World) and present your<br />

findings on a mind map.<br />

In her catalogue essay, Rachel Kent discusses how the artist’s Jewish<br />

heritage is invoked through the use <strong>of</strong> salt in many <strong>of</strong> her installations.<br />

In Jewish tradition, salt is used in ritual as an expression <strong>of</strong> mourning 11 .<br />

Think about why salt might be a loaded symbol in exploring the<br />

themes that inform her art making.<br />

Making it<br />

Choose a pr<strong>of</strong>essional field <strong>of</strong> environmental conservation that you<br />

are interested in, and conduct a research project into issues pertaining<br />

to your local area or state. Your findings will form the basis <strong>of</strong> an art<br />

project and/or installation, for which you may like to invite your family<br />

and friends to participate in the process.<br />

Think <strong>of</strong> a list <strong>of</strong> consumer waste materials, other than those used<br />

by Lauren Berkowitz in her MCA installations, which can be re-used<br />

or recycled. Research the work <strong>of</strong> other artists who employ these<br />

materials in their art practice. For example, Australian artist Robert<br />

Klippel made sculptures out <strong>of</strong> recycled metal, and Rosalie Gascoigne<br />

collected disused road signs as the basis for her art works. Create<br />

a body <strong>of</strong> work that utilises retrieved materials in order to promote<br />

environmental awareness.<br />

11 Rachel Kent, ‘Lauren Berkowitz’, In the Balance: <strong>Art</strong> for a Changing World, <strong>Museum</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>Contemporary</strong> <strong>Art</strong>, Sydney, 2010, p.30<br />

11

Diego Bonetto<br />

Diego Bonetto<br />

Weedyconnection 2008<br />

guided Tour <strong>of</strong> Steel Park,<br />

Canterbury, New South Wales<br />

Image courtesy and © the artist<br />

Photograph: Diego Bonetto<br />

12

Diego Bonetto<br />

Born 1969, Pinerolo, Italy. Lives and Works Sydney, New South Wales<br />

The Terrariums represent the environment outside, without any added trick or intrusion. The project 5 Terrariums, 5 Tours and a World <strong>of</strong> facebook<br />

Friends is yet another intervention <strong>of</strong> mine, using technology, social media, games, mock-up documentaries, etc, aimed time and time again at<br />

problematising the simplistic attitude towards nature that feeds our environmental legislation today. I believe in befriending nature. 12<br />

The interdisciplinary practice <strong>of</strong> multimedia artist and activist, Diego Bonetto, presents an<br />

alternative merger <strong>of</strong> ecological, economical and political imperatives in the move towards<br />

sustainable art practice. Through a deliberate veto <strong>of</strong> allegiance to any given media or material,<br />

Bonetto’s work has taken shape in many different forms, whether it be object-based, performative<br />

or experiential. His creative interventions <strong>of</strong>ten take place beyond the galleries walls, infiltrating a<br />

variety <strong>of</strong> unexpected social platforms and networks. His work to date covers the diverse fields <strong>of</strong><br />

sculptural installation, internet projects, video and online performances, cooking classes, lectures<br />

and guided/audio tours. Often site-specific and project-driven, Bonetto utilises his chosen medium<br />

as a vehicle to communicate, educate and generate discussion. As an ardent collaborator,<br />

Bonetto is also a key member <strong>of</strong> artist group SquatSpace, the Network <strong>of</strong> UnCollectable<br />

<strong>Art</strong>ists, and founder <strong>of</strong> the internet-based Weedyconnection 13 project, just to name a few.<br />

Perhaps the most alluring attribute <strong>of</strong> Bonetto’s practice is his ability to re-sensitise his audiences<br />

to the overlooked and neglected elements <strong>of</strong> our natural surroundings, elevating their reputation<br />

amongst all living things and reinstating their value within the wider ecosystem. Of particular<br />

interest to the artist are the numerous and varied non-indigenous species <strong>of</strong> ‘spontaneous flora’,<br />

commonly referred to as ‘weeds’, which sustain a persistent presence in his work, both physically<br />

and metaphorically. Through his work, the artist explores the idea that weeds represent a human<br />

desire for control rather than co-existence, highlighting the inequality inherent within such<br />

beloved colonial ideals as the manicured ‘front lawn’. 14 In drawing attention to this concept as a<br />

social construct, Bonetto suggests that the threatening and invasive nature <strong>of</strong> weeds is a common<br />

misconception, and like many other living organisms, they have an origin and a traditional use,<br />

along with an equal right to existence, rather than the notion that weeds are “pests”. Bonetto’s<br />

work also puts forward a challenging social critique <strong>of</strong> the metaphorical link between these<br />

‘unwanted’ species and current socio-political attitudes towards migration and cultural diversity.<br />

Diego Bonetto, 2010<br />

Bonetto’s contribution to this exhibition is spread generously throughout and beyond the<br />

reaches <strong>of</strong> the gallery precinct. 5 terrariums, 5 tours and a world <strong>of</strong> Facebook friends (2010)<br />

is a new three-part work comprising five sculptural terrariums (or garden enclosures)<br />

containing local soil samples and the weeds that spring forth from them; five public<br />

walking tours through Sydney’s parks and gardens in search <strong>of</strong> naturally-sprouting weeds;<br />

and a Facebook campaign for networkers to ‘befriend’ various species <strong>of</strong> spontaneous<br />

flora. 15 Mimicking the mobile sprouting ability <strong>of</strong> weeds, Bonetto’s terrariums spring<br />

up and inhabit unexpected alcoves throughout the MCA’s level 3 galleries. Beyond the<br />

installation, however, Bonetto intends to highlight our increasing disenchantment with<br />

the real world, by re-acquainting audiences with the natural inhabitants <strong>of</strong> our local<br />

urban sprawl. He aims to disrupt the social networks <strong>of</strong> our virtual environments with<br />

the dissemination <strong>of</strong> information pertaining rather, to our natural environment.<br />

Diego Bonetto<br />

5 terrariums, 5 tours and a world <strong>of</strong><br />

Facebook friends 2010 (detail)<br />

terrariums, soil from 5 locations in the Sydney Basin, guided<br />

tours <strong>of</strong> the locations, Facebook pr<strong>of</strong>iles <strong>of</strong> the plants visited<br />

5 Terrariums: 80 x 55 x 55 cm (each) Courtesy the artist<br />

Image courtesy and © the artist<br />

Photograph: Arnel Javíer Rodríguez<br />

12 Email correspondence with the artist, 20 July, 2010<br />

13 See www.squatspace.com and www.weedyconnection.com for more information<br />

14 Josephine Skinner, ‘Weeds <strong>of</strong> thought: on Diego Bonetto and sustainability’, 2009, unpublished, np.<br />

15 Rachel Kent, ‘Diego Bonetto: weedy connections’, In the Balance: <strong>Art</strong> for a Changing World, <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Contemporary</strong> <strong>Art</strong>, Sydney, 2010, p.34<br />

13

PRIMARY<br />

Thinking about it<br />

(K-2)<br />

What are weeds What makes them different to other kinds <strong>of</strong> plants<br />

Where do you find Diego’s ‘weedy’ installations in the gallery space<br />

Is this where you would normally find works <strong>of</strong> art Why do you think<br />

Diego has decided to put his weeds in places that are good for hiding<br />

(3-6)<br />

Can you identify any plant species that are known as weeds in your<br />

garden at home or at school Check out Diego’s website, Weedy<br />

Connection at http://www.weedyconnection.com and research some<br />

<strong>of</strong> the weeds that naturally occur in your area. Where do they originate<br />

from and are they useful for anything<br />

Making it<br />

Make your own weedy terrarium! A terrarium is a miniature landscape<br />

<strong>of</strong> living plants. You can be as creative as you like in choosing your<br />

container in which to house your plants. You can either plant your own<br />

seedlings or nurture them to grow, or leave your soil-filled terrariums<br />

outside and see what naturally sprouts up!<br />

Imagine what weeds from other countries look like. What about<br />

weeds from another planet Create your own new weed species using<br />

various sculptural materials. You might like to ‘plant’ your sculpture<br />

in a pot and put it on display in your classroom, along with an<br />

information label that states their place <strong>of</strong> origin and what they can be<br />

used for. Go wild with your wacky creations!<br />

SECONDARY<br />

Thinking about it<br />

(7-9)<br />

Check out Diego Bonetto’s weed campaign on Facebook. Why do you<br />

think he chose to include an online element in his work How does<br />

this virtual network-based intervention inform the sculptural elements<br />

displayed in the gallery space<br />

(10-12)<br />

Diego Bonetto draws his audience’s attention to the concept <strong>of</strong><br />

‘permissible species’ as a social construct, and uses weeds in his<br />

work as an apt metaphor for issues surrounding immigration and<br />

multiculturalism. Discuss the political aspects <strong>of</strong> Bonetto’s practice<br />

in relation to his chosen platforms <strong>of</strong> art production – installation,<br />

performance and the internet – and also the intentions behind these<br />

processes – to educate, infiltrate and ultimately change cultural<br />

perceptions.<br />

Making it<br />

Create a proposal and design layout for a Facebook campaign<br />

that promotes awareness for an environmental cause that is important<br />

to you. Consider the ways in which your audience will become involved<br />

in your online campaign: what Facebook applications will you utilise,<br />

what interactive elements will you provide, will you incorporate images<br />

and video clips, will your online ‘friends’ be invited to become active<br />

participants in your campaign, will you have a set objective or target to<br />

reach at the end<br />

If you could conduct a series <strong>of</strong> public tours, highlighting and informing<br />

locals <strong>of</strong> the weird and wonderful facts <strong>of</strong> their immediate surroundings<br />

that they may be completely oblivious to in the conduct <strong>of</strong> their day-today<br />

lives, what would it be about In how many ways could you extend<br />

this topic to develop a body <strong>of</strong> work that encompasses many different<br />

forms <strong>of</strong> artistic practice, such as sculpture, installation, documentary,<br />

performance, and online interventions<br />

14

Nici Cumpston<br />

Nici Cumpston<br />

Cultural landscape - Nookamka I 2008<br />

archival print on canvas, hand-coloured with pencil and<br />

watercolour 65 x 177 cm Image courtesy the artist and<br />

Gallerysmith, Melbourne © the artis<br />

15

Nici Cumpston<br />

Born 1963, Adelaide, South Australia. Lives and Works Adelaide, South Australia<br />

Language: Barkindji<br />

I feel like I am an investigator when I go out into the bush, as I am always photographing everything I see, like I am gathering evidence. 16<br />

Nici Cumpston, 2008<br />

Nici Cumpston is an Australian photographic visual artist with a uniquely diverse family background <strong>of</strong> Aboriginal, Afghan, Irish and English<br />

decent. Cumpston is widely recognised for her distinctively creative style <strong>of</strong> photography in which she hand-colours camera-captured images <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Australian landscape. Prior to her exhibiting career as an artist, Cumpston put her photographic skills to use working for the South Australian Police<br />

Department, and through this workplace experience, she developed a familiarity with the process <strong>of</strong> developing colour film, which was used to<br />

document speed and red light <strong>of</strong>fenses, as well as to crime scenes. 17<br />

Cumpston utilises her knowledge <strong>of</strong> the land and her Barkindji family heritage to study and explore the landscape – by foot, through lens and<br />

by hand. Once she has captured her documentary-like images on black and white film, she will add colour directly onto the processed negatives<br />

using transparent watercolours and pencils, which will then be scanned and printed digitally onto canvas. 18 This purposeful and painstaking process<br />

infuses the subject with an artificial likeness, lending Australia’s drought-stricken landscape to a compelling and ghostly hyper-real representation.<br />

Cumpston’s large panoramic landscapes <strong>of</strong> dried-up waterways and exhausted trees are here given a new aura <strong>of</strong> life through the artist’s colourising<br />

intervention.<br />

Paroo River<br />

Warrego River<br />

Culgoa River<br />

MacIn<br />

Through her series <strong>of</strong> photographic prints from 2008-10, Cumpston has documented the deteriorating landscape <strong>of</strong> Nookamka Lake, otherwise<br />

known as Lake Bonney – a shallow catchment area connected to the Murray Darling river system in South Australia. This once pristine Bourke and flourishing<br />

environment undeniably substantiates the ineffective and neglectful farming<br />

Wilcannia<br />

methods and abusive, unsustainable water usage thatthe river systems have<br />

NSW<br />

suffered over the last two hundred years since colonisation. 19<br />

Bourke<br />

Broken Hill<br />

The receding water levels <strong>of</strong> Nookamka have not only left behind a weary<br />

landscape <strong>of</strong> uprooted trees, but many Aboriginal artefacts and remains<br />

were exposed on dry land where they had once been concealed by water.<br />

These markings and burial grounds are evidence <strong>of</strong> the abiding customary<br />

connections Aboriginal people have had with this place for thousands <strong>of</strong><br />

years. Cumpston’s strong connection with her Indigenous descendants and<br />

their culture has instilled in her a great deal <strong>of</strong> passion for seeking out and<br />

recording the Barkindji people’s enduring relationship with the land, and as<br />

such, her eerie and evocative landscapes <strong>of</strong> Nookamka are<br />

Adelaide<br />

SA<br />

Adelaide<br />

SA<br />

Lake Bonney<br />

Broken Hill<br />

Lake Bonney<br />

Mildura<br />

Mildura<br />

Wilcannia<br />

VIC<br />

VIC<br />

Darling River<br />

Darling River<br />

Murray River<br />

Paroo River<br />

Hay<br />

Murray River<br />

Hay<br />

Warrego River<br />

Murrumbidgee River<br />

Murrumbidgee River<br />

Albury<br />

NSW<br />

Lachlan River<br />

Wagga Wagga<br />

Culgoa River<br />

Albury<br />

Lachlan River<br />

Cowra<br />

MacIntyre River<br />

Boggabilla<br />

Toomelah<br />

Wagga Wagga<br />

Cowra<br />

Sydney<br />

about people as they are about place. Though the recorded effects <strong>of</strong><br />

drought and water mismanagement have potentially starved Nookamka<br />

beyond rescue, Cumpston’s careful colouration appears to restore the<br />

landscape with a quiet dignity, and what remains in the space between real<br />

and imagined is a sense <strong>of</strong> responsibility and remorse for the memory <strong>of</strong> a<br />

vanishing place and its people.<br />

Above: Map <strong>of</strong> Nookamka Lake, otherwise known as Lake Bonney,<br />

a shallow catchment area connected to the Murray Darling river<br />

system in South Australia.<br />

16 Tess Allas, ‘Nici Cumpston’, Dictionary <strong>of</strong> Australian <strong>Art</strong>ists Online 2008, accessed 21/05/2010, .<br />

17 Ibid.<br />

18 <strong>Art</strong>ist’s statement, ‘Our People – Nici Cumpston’ University <strong>of</strong> South Australia News, accessed 21/05/2010, .<br />

19 Keith Munro, ‘Nici Cumpston’, In the Balance: <strong>Art</strong> for a Changing World, <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Contemporary</strong> <strong>Art</strong>, Sydney, 2010, p.62<br />

16

PRIMARY<br />

Thinking about it<br />

(K-2)<br />

Look at the trees in Nici’s photographs. How do you imagine they are<br />

feeling Why do you think they are feeling that way Choose a tree in<br />

one <strong>of</strong> the artworks and write a story from its point <strong>of</strong> view.<br />

(3-6)<br />

The absence <strong>of</strong> water is the main issue being addressed by Nici’s<br />

large-scale images <strong>of</strong> Lake Bonney. If a lot <strong>of</strong> the Lake’s water supply<br />

is missing, what else do you think is missing from these landscapes<br />

What kind <strong>of</strong> plants and animals rely on water to survive and are<br />

therefore absent from these images<br />

Making it<br />

Using simple craft materials, like cardboard, create a photo-shaped<br />

viewfinder to explore your local landscape and waterways. Much like<br />

the way Nici uses her camera to capture a landscape image, use your<br />

viewfinder to ‘frame’ your landscape image, then draw it onto white<br />

paper using lead pencil. Then fill in this black and white image with<br />

colour, using pencils, textas, watercolours and collage materials to<br />

create a multi-layered landscape <strong>of</strong> different colours and textures.<br />

In groups or as a class, research the history <strong>of</strong> Lake Bonney and how it<br />

has changed over the many years since European settlement. Create<br />

an illustrated timeline <strong>of</strong> Lake Bonney’s history, including any recent<br />

attempts to improve the environmental conditions <strong>of</strong> the Lake, as well<br />

as any future plans for development.<br />

SECONDARY<br />

Thinking about it<br />

(7-9)<br />

Lake Bonney, like many other regions along the Murray Darling River<br />

system, has been significantly altered since European settlement due<br />

to the effects <strong>of</strong> drainage schemes and other environmental impacts.<br />

Research the history <strong>of</strong> Lake Bonney, including its previous recreational<br />

uses, poor water management schemes, local sources <strong>of</strong> pollution and<br />

causes for degradation. How does this inform your understanding <strong>of</strong><br />

Cumpston’s two prints, Cultural landscape – Nookamka I & Nookamka<br />

III What ideas does the title ‘Cultural landscape’ bring to mind<br />

(10-12)<br />

Take a close look at Campsite, Nookamka Lake V (2010) and Scar tree,<br />

Nookamka Lake (2008). The process involved in making these images<br />

is highly detailed and complex. Compare and contrast Cumpston’s<br />

artistic practice <strong>of</strong> hand-colouring black and white negatives and<br />

printing digitally onto canvas with the process <strong>of</strong> colour photography<br />

printed onto photographic paper. What are the differences in both the<br />

material and conceptual effect How does the artist’s chosen process<br />

add meaning<br />

Making it<br />

In pairs or groups, research different ways in which the landscape<br />

<strong>of</strong> Lake Bonney may be rescued or revitalised. Discover some <strong>of</strong> the<br />

principles <strong>of</strong> ecologically sustainable development and research<br />

various government projects that aim to increase biodiversity,<br />

improve environmental management and provide sustainable<br />

water management schemes. Create a large-scale landscape image<br />

that depicts Lake Bonney in 20 years time under your sustainable<br />

waterways plan, including the changes you would have implemented<br />

and their long-term environmental benefits.<br />

Using your local knowledge <strong>of</strong> your area, create a body <strong>of</strong> work<br />

that explores the environmental degradation <strong>of</strong> a location, area<br />

or region that is important to you or your family. How would you<br />

depict the landscape in order to draw attention to its ecological<br />

mismanagement<br />

17

Janet Laurence<br />

Janet Laurence<br />

Cellular Gardens (where breathing begins) 2005<br />

stainless steel, mild steel, acrylic, blown glass, rainforest plants<br />

dimensions variable<br />

<strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Contemporary</strong> <strong>Art</strong>, purchased 2005<br />

Image courtesy and © the artist<br />

18

Janet Laurence<br />

Born 1947, Sydney, New South Wales. Lives and Works in Sydney, New South Wales<br />

Both works address the fragility <strong>of</strong> our living environment. I’m interested in our interconnection and dependency on this environment<br />

and our own implication in its despoliation and loss. My concern has been the loss <strong>of</strong> habitat and resultant destruction <strong>of</strong> ecosystems<br />

and tragic decimation <strong>of</strong> species.<br />

Both m y breathing animals in ‘Vanishing’ and the plants in ‘Cellular Gardens’ could be seen as refugees from their natural habitat,<br />

with both on a form <strong>of</strong> life support.<br />

Janet Laurence, 2010<br />

Leading Australian artist, Janet Laurence, has maintained a strong personal commitment to promoting the preservation <strong>of</strong> our natural environment<br />

through her art, and continues to do so with an ever-increasing sense <strong>of</strong> urgency and devotion. Laurence’s work has always been inspired and<br />

informed by nature, driven by strong ecological imperatives and a deep-seated understanding <strong>of</strong> the interconnections that bind all matter, from the<br />

microcosm to the macrocosm, and from both the natural and built environments. Fixated on examining the interaction between nature and culture,<br />

Laurence’s work occupies a unique space in which art, science, memory and imagination meet.<br />

Laurence embraces a range <strong>of</strong> media and materials in her practice, extending across locations and forms in response to specific sites and<br />

environments. Along with an impressive record <strong>of</strong> gallery representation, Laurence is also well-known for her public commissions and architectural<br />

collaborations, most notably in Sydney for her project, Edge <strong>of</strong> Trees (1994-95), made in collaboration with Fiona Foley, and installed in the forecourt<br />

<strong>of</strong> the <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> Sydney; as well as her reparative waterway installation, In the Shadow (1998), at Sydney Olympic Park in Homebush Bay.<br />

Consistent with intimate gallery presentations and large-scale outdoor installations is the engagement with the environment and architecture.<br />

Since the late 1990s, Laurence’s work has expressed an increasing concern for the ominous aspects <strong>of</strong> human occupation that have resulted in<br />

environmental devastation such as wide-scale deforestation, land degradation, the depletion <strong>of</strong> precious natural resources and the diminishing <strong>of</strong><br />

species. 20 In this exhibition, we see two very different approaches to Laurence’s consistent thematic exploration <strong>of</strong> the fragile balance that exists<br />

between all natural and living things and the consequences <strong>of</strong> human activity driven by pr<strong>of</strong>it and greed. Exemplifying the diversity <strong>of</strong> her practice,<br />

these sculptural and video installations come together to create an intimate space for interaction and immersion, inviting the audience to linger,<br />

reflect and contemplate.<br />

Upon entering the space, viewers initially encounter the amplified sound <strong>of</strong> breathing. Vanishing (2009-10) is a new work filmed during the artist’s<br />

three month residency at Taronga Zoo in 2009. It comprises <strong>of</strong> a two-screen video projection revealing the contours, thick furs, curled claws and<br />

the gentle breathing motions <strong>of</strong> various endangered species, in a tranquil layering <strong>of</strong> imagery and sound. Through this work, Laurence has created<br />

a sense <strong>of</strong> ‘slowed space’, engaging with the architectural environment <strong>of</strong> the gallery to draw our attention to the beauty and vulnerability <strong>of</strong> the<br />

animal realm, suggesting that if we can slow down in time enough to reflect, then perhaps the world may stop changing for the worse.<br />

Breath continues as a parallel theme in Laurence’s remedial installation, Cellular Gardens (where breathing begins) (2005). Revealing her fascination<br />

with nature and systems through which it can be examined, collected and displayed, Cellular Gardens presents a series <strong>of</strong> glass vessels mounted<br />

on slender steel supports. Tenuously housing a selection <strong>of</strong> young rainforest saplings, these glass vials function like a gathering <strong>of</strong> miniature<br />

glasshouses, at once a site for germination, experimentation and preservation. Comparable to the vitreous equipment <strong>of</strong> a science laboratory or<br />

a medical life-support unit, the delicate plant specimens are interconnected by a system <strong>of</strong> tubes, exploring the notion that science has become<br />

integral to the way in which we relate to our natural surroundings. Whether this piece is a futuristic botanical shrine to a long-lost species, or a<br />

disturbing preview <strong>of</strong> the immanent alternative measures that loom along our current path <strong>of</strong> destruction, Laurence’s ecological agenda is evident.<br />

By bringing into her art a close examination <strong>of</strong> the fragility <strong>of</strong> the plant and animal realms, and the threat that we pose to them for the fate <strong>of</strong> future<br />

generations, Laurence poetically draws our attention to the issues that concern us all and resonate with today’s eco-conscious world.<br />

20 Rachel Kent, ‘Changing topographies: the environmental art <strong>of</strong> Janet Laurence’, catalogue essay in Janet Laurence: A Survey Exhibition, Drill Hall Gallery, Australian National University,<br />

Canberra, 2005, p.16.<br />

19

PRIMARY<br />

Thinking about it<br />

(K-2)<br />

What animals can you see in Janet’s video work, Vanishing Where<br />

might you find these animals What parts <strong>of</strong> the animals can you see<br />

close-up What words can you think <strong>of</strong> to describe their features, like<br />

their fur, their claws or their snouts<br />

(3-6)<br />

Look at Janet’s installation Cellular Gardens (where breathing begins)<br />

and discuss what you think the system <strong>of</strong> tubing might represent. What<br />

does it remind you <strong>of</strong> What does it make you think <strong>of</strong>, and how does it<br />

make you feel Use your imagination!<br />

Making it<br />

On your own or in groups, research some endangered plant species<br />

and create a series <strong>of</strong> drawings. You might like to cut out your drawings<br />

and make a mobile to hang them from, present them in a diorama,<br />

or include your drawings in a poster that promotes the conservation <strong>of</strong><br />

your chosen plant species.<br />

Go big and collaborate with your classmates to create an indoor plant<br />

sanctuary. You might like to use real plants and watch them grow, or<br />

make your own futuristic botanical species using various sculptural<br />

materials. (Hint: patty-cake cups make great flowers, or look up<br />

some ways you can make your own blooms using origami!)<br />

SECONDARY<br />

Thinking about it<br />

(7-9)<br />

The audio aspects <strong>of</strong> video installation can carry a lot <strong>of</strong> meaning<br />

in terms <strong>of</strong> setting the mood, conveying feeling and triggering<br />

an emotional response. Close your eyes and listen carefully to<br />

Janet Laurence’s video, Vanishing. What do you understand <strong>of</strong> the<br />

work just by listening to it Then open your eyes and turn to look at<br />

Laurence’s Cellular Gardens, in the same room - how does the audio <strong>of</strong><br />

the video piece affect your interpretation <strong>of</strong> her sculptural installation<br />

(10-12)<br />

Our ability to breath is fundamental to our existence and is facilitated<br />

by the plant life that surrounds us. Breath is also fundamental to the<br />

art <strong>of</strong> glassblowing, which was used to create the vessels that house<br />

the rainforest plantlets in Cellular Gardens (where breathing begins).<br />

Discuss the importance <strong>of</strong> the relationship between the artist’s concept<br />

and her chosen media in communicating meaning, with reference to<br />

both <strong>of</strong> Janet Laurence’s installation pieces.<br />

Making it<br />

Research an endangered plant or animal species that is native to<br />

your region or state. Create an artwork or body <strong>of</strong> work that explores<br />

the fragility and vulnerability <strong>of</strong> this species and draws attention to<br />

the precarious nature <strong>of</strong> its existence. You might like to incorporate<br />

drawing, photography, collage, installation or film.<br />

Janet Laurence has long been fascinated by glasshouses and<br />

other cultural constructs that function as sites <strong>of</strong> display, cultivation<br />

and conservation for botanical species. Explore a variety <strong>of</strong> these<br />

structures and systems that facilitate the examination, collection<br />

and display <strong>of</strong> the natural world, such as science laboratories,<br />

natural history museums, botanical gardens and glasshouses. Create<br />

your own artwork that re-interprets their function, purpose and<br />

methods <strong>of</strong> display.<br />

20

James Newitt<br />

James Newitt<br />

Landscape (detail) 2009<br />

type C photographs<br />

30 photographs: 20 x 30 cm (each); 200 x 180 cm (installation, approx.)<br />

Courtesy the artist and Criterion Gallery, Hobart, Tasmania Image courtesy the artist and Criterion Gallery, Hobart © the artist<br />

21

James Newitt<br />

My primary aim is to investigate the capacity for visual art to identify, describe and elaborate relationships between people and place. By focusing on<br />

relationships that are fragile, subtle, complex or in a state <strong>of</strong> change I aim to reveal micro-histories and subjective experiences that bind people into<br />

communities and to place. 21 James Newitt, 2007<br />

Since branching out from his formal training as a graphic designer, James Newitt has swiftly become one <strong>of</strong> the more prominent new media<br />

artists currently working in Tasmania. His video and photography works <strong>of</strong>ten incorporate objective documentary strategies, using observation and<br />

interviewing in tandem with facilitated performance and experimental narratives. Newitt explores concepts surrounding individual and collective<br />

identity, community memory, and a sense <strong>of</strong> place. In 2007, Newitt completed his doctorate in Fine <strong>Art</strong>s at the University <strong>of</strong> Tasmania’s<br />

School <strong>of</strong> <strong>Art</strong>, and was this year appointed as the School’s Associate Lecturer in Fine <strong>Art</strong>s, specialising in visual communication. Concerned with<br />

the inherent complexities <strong>of</strong> human social engagement, Newitt’s artistic practice is informed by his ongoing research into social and cultural<br />

relationships with place, as well as his own personal experiences. As such, many <strong>of</strong> Newitt’s new media works predominantly focus on localised issues<br />

and situations specific to his homeland <strong>of</strong> Tasmania, such as his 2007 project, Saturday Nights, in which the artist facilitated a country-dance in a<br />

small town hall on the Tasman Peninsula in Southern Tasmania, five kilometres from the site <strong>of</strong> the Port <strong>Art</strong>hur Massacre, and filmed on the 10 th<br />

anniversary <strong>of</strong> the tragedy. 22<br />

Newitt’s single-channel video work, Passive Aggressive (2009), and corresponding suite <strong>of</strong> 30 photographs titled Landscape (2009), are both part <strong>of</strong><br />

a body <strong>of</strong> work that investigates the long-standing social tensions between forestry workers and environmental activists in the Upper Florentine Valley<br />

<strong>of</strong> south-western Tasmania. For years, Government and privately-owned companies have been logging this expansive region <strong>of</strong> old growth forests<br />

that border the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area. In an ongoing campaign <strong>of</strong> political lobbying and environmental retribution,<br />

anti-forestry activists have devoted themselves to obstruct forestry practices by taking action in creative, rebellious and sometimes dangerous ways.<br />

Newitt utilises the familiar vehicles <strong>of</strong> documentary, film and photography to record the interactions between the police, loggers and protestors in the<br />

Upper Florentine Valley. His photographs capture the strategies used by protestors to disrupt the attempts <strong>of</strong> developers by ‘blocking roads, building<br />

elaborate rope structures attached to logging machines to make them inoperable, and establishing tree-sits to draw attention to their campaign.’ 23<br />

Collectively, these two works actively engage with the quarrels and controversy surrounding a specific time, location and community, without<br />

resorting to mere social commentary, and maintain a critical distance from the situation at hand by focusing instead on exploring the relationships<br />

between people and place.<br />

21 James Newitt, Relational Perspectives: A Visual Investigation into Social and Cultural Relationships with Space, PhD exegesis, University <strong>of</strong> Tasmania, 2007, p.13<br />

22 ‘Stories <strong>of</strong> Celebration and Dissent’, Rosalux Gallery, <br />

23 Elise Routledge,’James Newitt’, In the Balance: <strong>Art</strong> for a Changing World, <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Contemporary</strong> <strong>Art</strong>, Sydney, 2010, p.124<br />

22

PRIMARY<br />

Thinking about it<br />

(K-2)<br />

Look at the pictures in James’ photographic series, Landscape (2009).<br />

What is happening Who are the people in the photos Do the photos<br />

tell a story Where else might you find images like this On the TV<br />

news In the newspaper<br />

(3-6)<br />

James has used two pieces <strong>of</strong> equipment to create two different works<br />

that both relate to the same story. Can you identify them Discuss the<br />

varying affects that artists can create by altering their materials and<br />

techniques. Do you think they tell the same story in a different way<br />

How<br />

Making it<br />

What is something in your life that you would want to save if it were<br />

threatened Why is this thing so important to you Create a poster,<br />

photographic series or video that explores this idea.<br />

Think about the debate that is taking place in James’ video<br />

and photographic work between the forestry workers and the<br />

environmental activists. Create a poster you could use in an<br />

environmental campaign.<br />

SECONDARY<br />

Thinking about it<br />

(7-9)<br />

Watch James Newitt’s Passive Aggressive (2009) video closely and<br />

consider the technical and stylistic elements <strong>of</strong> the work, such as<br />

camera angles, moving and/or static camera shots, editing processes,<br />

audio overlays, scene durations, etc. Think about the ways in which<br />

these elements feed into a documentary style <strong>of</strong> filming and how this<br />

affects the way audiences will interpret the work.<br />

Do you think Newitt’s style creates an objective or subjective experience<br />

for the viewer Debate this in class.<br />

How does this work differ from a documentary, or a news piece What<br />

view is he putting forward What is his agenda, if any<br />

(10-12)<br />

Conduct further research into the forestry activity and environmental<br />

lobbying that has taken place in the Upper Florentine Valley in southwestern<br />

Tasmania. From your findings, discuss how you think James<br />

Newitt brings about an awareness <strong>of</strong> the broader implications <strong>of</strong> this<br />

conflict through his film and photographic work. Do you think his work<br />

raises significant questions relating to power and responsibility If so,<br />

how Consider the implications <strong>of</strong> this pertaining to the individual,<br />

community, commercial business, organisations and industry.<br />

How does the artist bring about awareness <strong>of</strong> the broader implications<br />

<strong>of</strong> this conflict and raise significant questions relating to power and<br />

responsibility<br />

Franklin River<br />

Gordon River<br />

Tarkine region<br />

TAS<br />

Upper<br />

Florentine<br />

Valley<br />

Lake<br />

Gordon<br />

Lake<br />

Pedder<br />

Styx<br />

Valley<br />

Florentine River<br />

Southwest<br />

National Park<br />

Making it<br />

Much <strong>of</strong> James Newitt’s video work is shaped through research and<br />

personal experience. Choose an important environmental issue that<br />

affects your school and/or local community. Develop a body <strong>of</strong> work<br />

that could be used to educate or inform the community about this<br />

issue. If there are two parties in opposition over the issue, will you<br />

decide to present the position/opinion <strong>of</strong> both sides Your artwork may<br />

take the form <strong>of</strong> a painting, sculpture, photography, installation, video<br />

or brochure.<br />

Above: Map <strong>of</strong> Upper Florentine Valley, Tasmania, where Passive Aggressive (2009) and<br />

Landscape (2009) were made.<br />

Start an archive <strong>of</strong> environmental conservation articles featured in the<br />

newspapers. Think about how the author’s opinions and perspectives<br />

can influence the representation <strong>of</strong> both written and visual content.<br />

Develop a project brief for a documentary video work based on an<br />

issue surrounding some <strong>of</strong> your findings. Think about the camera’s<br />

ability to capture a moment in time. How might you approach the<br />

project in order to objectively convey the environmental issue and<br />

its circumstances, as well as capture the subjective responses and<br />

opinions <strong>of</strong> those affected by it How will you propose to document the<br />

issue and capture its social significance to the community at large<br />

23

Jeanne van Heeswijk<br />

Jeanne van Heeswijk and Paul Sixta<br />

Talking Trash -- personal relationships with waste 2010<br />

type C photographs on dibond<br />

25 prints: 35 x 34 cm (each)<br />

Courtesy the artists<br />

Image courtesy and © the artists<br />

24

Jeanne van Heeswijk<br />

Born 1965, Schijndel, the Netherlands. Lives and Works in Rotterdam, the Netherlands<br />

<strong>Art</strong> has the capacity to contribute to life. From within the realm <strong>of</strong> art I try to create platforms where people can meet. It is vital that I am inside the<br />

community, become a part <strong>of</strong> it, and develop the ability to ‘listen’. I want to encourage people to take an active part in what I see as the starting point <strong>of</strong><br />

processes that may continue, which will ultimately give them more control over their environment. 24 Jeanne van Heeswijk, 2004<br />

For almost a decade, Dutch artist Jeanne van Heeswijk has dedicated her artistic practice to embarking on lengthy and socially strategic art projects<br />

that originate from, and take place within, the public realm. Committed to providing communities with agency in the art making process, van<br />

Heeswijk has gained international recognition and critical attention for her socially engaged works that generate communication frameworks<br />

where new relations and connections can be established. Often realised through community partnerships or in collaboration with other artists,<br />

designers, architects and s<strong>of</strong>tware developers, the projects invariably become a process <strong>of</strong> mediation between the vision <strong>of</strong> the artist and that <strong>of</strong><br />

her collaborators and volunteers. Though van Heeswijk’s ventures always commence with a strong and deliberate concept, the methodology <strong>of</strong> her<br />

practice lends itself to a process <strong>of</strong> negotiation and counter-action, and the outcomes <strong>of</strong>ten remain open-ended.<br />

Talking Trash –- personal relationships with waste (2010) was produced earlier this year by the artist in partnership with the C3West initiative and<br />

Veolia Environmental Services, an international waste management company, and was exhibited at Goulburn Regional Gallery from April to May<br />

2010. Working in close collaboration with filmmaker Paul Sixta to realise this project, van Heeswijk visited 25 households in Goulburn and Liverpool<br />

to talk about people’s diverse relationships with waste.<br />

Talking Trash began as a series <strong>of</strong> conversations conducted by van Heeswijk with volunteers across both communities. In posing the question, “what<br />

do you waste” the artist received detailed descriptions <strong>of</strong> personal approaches and practical actions taking place in the household or workplace,<br />

all in relation to waste. 25 The resulting dialogues presented a variety <strong>of</strong> individual perspectives on the concept <strong>of</strong> waste, ranging from the localised<br />

to global in scale, and anywhere in between, from predictable ecological concerns like wasting water, to more unexpected metaphorical matters,<br />

such as the loss <strong>of</strong> wasted time. From the initial conversation, the artist then scripted a short two to three minute narrative, which she then asked<br />

her participants to re-enact in front <strong>of</strong> Sixta’s camera. These ‘mini-clips’ are presented in the exhibition, along with a single-channel video work<br />

describing the transit and disposal <strong>of</strong> garbage from Sydney homes to landfill areas outside <strong>of</strong> Goulburn, and a display <strong>of</strong> objects donated by the<br />

project’s participants, which are central to their stories. 26<br />

In its exhibition format, van Heeswijk’s interventionist project presents a different kind <strong>of</strong> documentary, occupying an ambiguous space between<br />

reality and fiction, as well as turning private acts into public awareness. 27 Not only does van Heeswijk’s project <strong>of</strong>fer a unique insight into the<br />

community as it anticipates the necessity for revolution in the face <strong>of</strong> climate change predictions, but it also serves as a re-affirmation that the waste<br />

<strong>of</strong> our lives is as complex as it is consequential.<br />

24 Mirjam Westen, interview with the artist, ‘Jeanne van Heeswijk: The <strong>Art</strong>ist as Versatile Infiltrator <strong>of</strong> Public Space. Urban Curating in the 21st Century’, 2004, np.<br />

25 Abigail Moncrieff, Talking Trash – Personal Relationships with Waste, exhibition publication, <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Contemporary</strong> <strong>Art</strong>, 2010, np.<br />

26 Abigail Moncrieff, ‘You Are Not Alone’, In the Balance: <strong>Art</strong> for a Changing World, exhibition catalogue, <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Contemporary</strong> <strong>Art</strong>, Sydney, 2010, p.96<br />

27 Abigail Moncrieff, Talking Trash – Personal Relationships with Waste, exhibition publication, <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Contemporary</strong> <strong>Art</strong>, 2010, np.<br />

25

PRIMARY<br />

Thinking about it<br />

(K-2)<br />

What is waste What kind <strong>of</strong> things do we throw away<br />

Look at the objects chosen by Jeanne’s participants to be exhibited<br />

in the gallery. Objects can be special to a person for many different<br />

reasons. Do you own something that is important to you, but might be<br />

‘junk’ to somebody else<br />

(3-6)<br />

Where does waste go Research the process <strong>of</strong> waste removal and<br />

recycling in your school or local area. Can you think <strong>of</strong> new ways to<br />

reduce the waste you produce at school or at home<br />

Making it<br />

Start a collection box in your classroom and ask your classmates to<br />

bring in clean waste and recycle items, like egg cartons, cereal boxes,<br />

milk bottles or old newspapers. Either on your own or in groups, create<br />

an artwork using these materials. You could hold an exhibition <strong>of</strong> your<br />

‘trashy triumphs’!<br />

Conduct an interview with a friend or family member and ask them<br />

the question, ‘what do you waste’. From their response, develop an<br />

artwork that describes your participant’s personal view towards waste.<br />

What might be your personal view<br />

SECONDARY<br />

Thinking about it<br />

(7-9)<br />

Jeanne van Heeswijk’s project is about creating dialogue and the<br />

possibilities for social change. What outcomes do you think she set out<br />

to achieve through this project, if any<br />

Do you think the project is successful in solving the problem <strong>of</strong> waste<br />

If not, what do you think it has achieved How does the art context<br />

<strong>of</strong> this work inform the way you interpret the information presented<br />

through van Heeswijk’s gallery installation<br />

(10-12)<br />

Some <strong>of</strong> the terms used by art critics to describe the role assumed by<br />

Jeanne van Heeswijk include ‘mediator’, ‘versatile infiltrator <strong>of</strong> public<br />

space’ and ‘community worker’. The artist describes herself as an<br />

‘urban curator’.<br />

Do you think van Heeswijk’s interventions belong to the realm <strong>of</strong> art<br />

Why<br />

Making it<br />

Either on your own or in a group, develop your own documentarystyle<br />

art project that explores a significant environmental issue. What<br />

documentary formats will you utilise – video, photography, written<br />

texts and/or oral testimonies Don’t forget the active elements <strong>of</strong><br />

collecting information, such as meeting, interviewing, listening and<br />

responding. How will you present your findings in a meaningful and<br />

informative art installation<br />

Prepare to make a documentary video <strong>of</strong> the waste and<br />

recycling practices <strong>of</strong> the members <strong>of</strong> your own household. Use a<br />

storyboard to plan how you would go about realising your project in<br />

terms <strong>of</strong>: conducting interviews (if any), who you would film, what<br />

you would ask them, working from script or editing live shots, camera<br />

angles and frames, the mood you want to create, the message you<br />

want to convey to your audience, and how you would install and<br />

exhibit your work.<br />

26

Glossary<br />

Barkindji<br />

The Barkindji People are an Aboriginal clan from the<br />

western region <strong>of</strong> New South Wales. Barkindji can<br />

also be referred to as Paarkindji or Paarkantji<br />

Colonisation<br />

A process by which a different system <strong>of</strong> government is established<br />

by one nation over another group <strong>of</strong> peoples. It involves the<br />

colonial power asserting and enforcing its sovereignty according<br />

to its own law, rather than by the laws <strong>of</strong> the colonised<br />

Consumables<br />

A material or product that is produced for consumption;<br />

that is consumed or depleted upon use<br />

Commission<br />

An artwork that is produced specially to an order<br />

Darling River<br />

The Darling River is the fourth longest river in Australia,<br />