Bocas del Toro Research Station - Smithsonian Tropical Research ...

Bocas del Toro Research Station - Smithsonian Tropical Research ...

Bocas del Toro Research Station - Smithsonian Tropical Research ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

EVA TOTH<br />

<strong>Smithsonian</strong> Institution Postdoctoral Fellow<br />

(2004), <strong>Smithsonian</strong> Marine Science Network<br />

Postdoctoral Fellow (2005-2007)<br />

Comparing the importance of colony relatedness<br />

and environmental factors in the evolution of<br />

eusociality in snapping shrimp<br />

The fact that social insects such as ants, honeybees,<br />

and termites give up their own chance to reproduce<br />

in order to help rear the offspring of one or a few<br />

individuals did not make much sense to Darwin,<br />

who thought that individuals maximize their own<br />

survival and reproduction. However, by helping<br />

their relatives, truly social (eusocial) animals may<br />

propagate their own genes indirectly.<br />

Social shrimp live in the internal canals of sponges<br />

and probably eat sponge tissue or detritus. Colony<br />

size ranges from tens to hundreds of individuals,<br />

depending on the species, colony age and sponge<br />

size. One or a few large queens produce all of the<br />

offspring from the colony. Once their eggs are<br />

fertilized, queens carry them in their abdominal<br />

pouch until they hatch. The rest of the colony<br />

consists of juveniles of different sizes and larger<br />

animals without developed gonads. Most are the<br />

queen’s offspring. The larger animals defend the<br />

sponge, and thus the colony, against intruders.<br />

Because social shrimp were discovered fairly<br />

recently and because they live underwater, they are<br />

one of the least-studied groups of social animals.<br />

Toth has been working to fill in the basic<br />

information that will help us to understand how<br />

these societies evolved. She has been developing<br />

and using genetic tools to see how closely related<br />

the animals are in each colony. She has also used<br />

behavioral experiments to examine interactions<br />

between colony members.<br />

13<br />

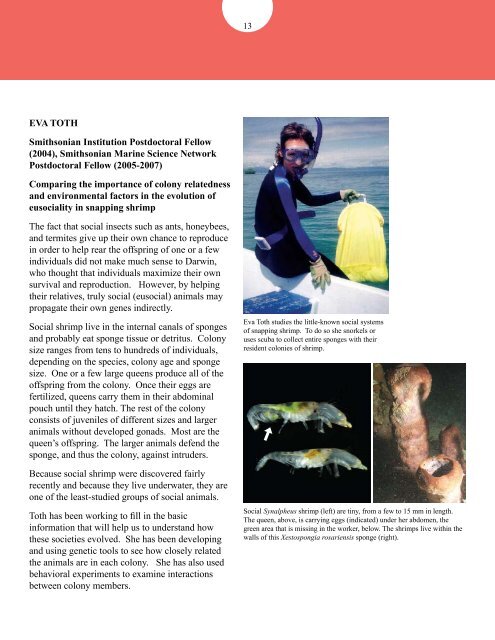

Eva Toth studies the little-known social systems<br />

of snapping shrimp. To do so she snorkels or<br />

uses scuba to collect entire sponges with their<br />

resident colonies of shrimp.<br />

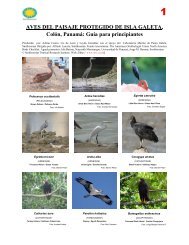

Social Synalpheus shrimp (left) are tiny, from a few to 15 mm in length.<br />

The queen, above, is carrying eggs (indicated) under her abdomen, the<br />

green area that is missing in the worker, below. The shrimps live within the<br />

walls of this Xestospongia rosariensis sponge (right).