JUVENILE JUSTICE - The Bar Association of San Francisco

JUVENILE JUSTICE - The Bar Association of San Francisco

JUVENILE JUSTICE - The Bar Association of San Francisco

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

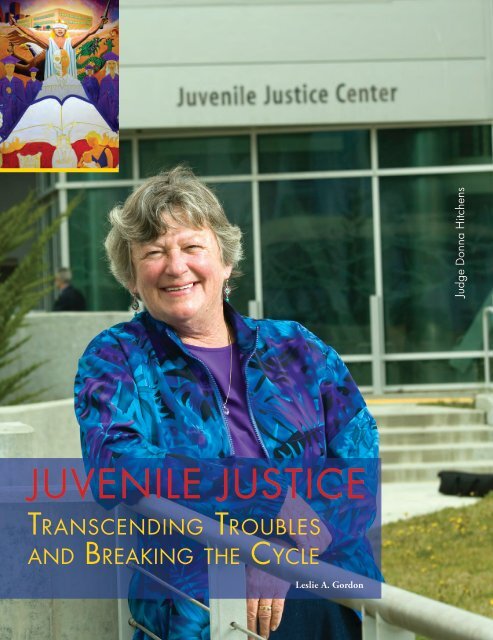

Judge Donna Hitchens<br />

<strong>JUVENILE</strong> <strong>JUSTICE</strong><br />

Transcending Troubles<br />

and Breaking the Cycle<br />

Leslie A. Gordon<br />

16 SUMMER 2009

One <strong>of</strong> the principle tenets <strong>of</strong> juvenile court is<br />

that all proceedings are confidential. As a result,<br />

juvenile courts, which are a part <strong>of</strong> <strong>San</strong><br />

<strong>Francisco</strong>’s Unified Family Court, are mysterious<br />

places to most people. But the attorneys who practice<br />

there—along with the judges—are part <strong>of</strong> a distinct<br />

universe, where lawyers on opposing sides have close relationships<br />

and, uniquely, the same goal: to help troubled<br />

youth navigate the system and to get them the help they<br />

need so they can get on with their lives.<br />

Because cases involving youth are <strong>of</strong>ten complicated by<br />

psychological, educational, and behavioral issues, problems<br />

cannot necessarily be solved by a legal resolution<br />

alone. As a result, attorneys in this area also have to be<br />

quasi social workers.<br />

Meanwhile, under the mandates <strong>of</strong> the California Welfare<br />

and Institutions Code, judges face the very tricky task<br />

<strong>of</strong> formulating the “least restrictive” plan for delinquent<br />

juveniles while still protecting the community. Resolving<br />

tension between rehabilitation and punishment is especially<br />

challenging when many kids in the system have<br />

absent parents and, increasingly, mental health problems<br />

including posttraumatic stress disorder from witnessing<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>ound violence, with many <strong>of</strong> the problems cycling<br />

through generations <strong>of</strong> families.<br />

Yet <strong>San</strong> <strong>Francisco</strong> has built a reputation for cutting-edge<br />

approaches with collaborative justice programming.<br />

Commonly referred to as “problem-solving” courts, the<br />

collaborative courts combine judicial supervision with rehabilitation<br />

services. It requires an unusual, coordinated<br />

effort among attorneys, law enforcement, and public service<br />

agencies.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Youth Family Violence Court, for instance, was<br />

founded specifically to rehabilitate youth who have committed<br />

violence toward a family member or in the context<br />

<strong>of</strong> a dating relationship. Services include court supervision<br />

and appearances, violence intervention programs, mental<br />

health services, and child trauma services.<br />

Similarly, the Youth Treatment and Education Center<br />

runs three programs for youth in the juvenile justice system.<br />

<strong>The</strong> core program is the Principal Center Collaborative,<br />

a high school for youth on probation that integrates<br />

behavioral health services<br />

within the school day.<br />

<strong>San</strong> <strong>Francisco</strong>’s unique Unified<br />

Family Court and collaborative<br />

courts create<br />

multiple stakeholders in<br />

the success <strong>of</strong> youth in the<br />

system, including judges,<br />

district attorneys, public<br />

defenders, panel attorneys,<br />

court administrators, community organizations, and<br />

pro bono lawyers. In contrast to typical adversarial<br />

relationships, these stakeholders problem-solve collaboratively,<br />

making youth law both one <strong>of</strong> the most troubling<br />

and and also one <strong>of</strong> the most rewarding areas to<br />

practice law.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Judge<br />

Perhaps no person is more responsible for improvements<br />

in the administration <strong>of</strong> youth law in <strong>San</strong> <strong>Francisco</strong><br />

than Donna Hitchens, supervising judge <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Unified Family Court.<br />

After founding the National Center for Lesbian Rights,<br />

Hitchens won election in 1990 to an open seat on the<br />

bench. She soon witnessed many overlapping issues slip<br />

through the administrative cracks and set forth to unify<br />

the family courts.<br />

As a result, family court judges now take a holistic approach<br />

to families, with delinquency, dependency, family<br />

law, and child support cases all coordinated. Today,<br />

if a foster youth (dependency court) gets arrested (delinquency<br />

court), the two judges are now aware <strong>of</strong> both<br />

cases. For the moment, the courts are not colocated:<br />

delinquency (criminal matters) is at the <strong>San</strong> <strong>Francisco</strong><br />

Youth Guidance Center (YGC), also known as juvenile<br />

hall, in Twin Peaks; dependency, family law, and child<br />

support are at the Civic Center Courthouse.<br />

“<strong>The</strong> goal is ‘one family, one judge.’ We’re not there exactly,<br />

but we’re close. We’ve made a 90 percent improvement,”<br />

Hitchens says during an interview in her chambers,<br />

which is decorated with bears and other stuffed<br />

animals and a framed “I love you mom” card.<br />

Youth Guidance Center photos by Jim Block except as noted.<br />

THE BAR ASSOCIATION OF SAN FRANCISCO SAN FRANCISCO ATTORNEY 17

Today, the growing number<br />

<strong>of</strong> youth in the system with<br />

serious mental health issues and<br />

the dwindling resources to help<br />

them is “an incredible problem,”<br />

she says. “In my opinion,<br />

it’s the result <strong>of</strong> violence<br />

in the home and in the community.<br />

Many <strong>of</strong> the kids<br />

have undiagnosed posttraumatic<br />

stress disorder.”<br />

Fortunately, Hitchens adds, <strong>San</strong> <strong>Francisco</strong> has “an incredibly<br />

dedicated group <strong>of</strong> attorneys” working together to<br />

help them. “<strong>The</strong> PDs, the DAs, the panel attorneys: it’s a<br />

community.” <strong>The</strong>y may technically be on opposing sides<br />

<strong>of</strong> a case, but, “ultimately, they do want the same thing.”<br />

Anyone practicing law in this area must be “incredibly patient,”<br />

Hitchens adds. “You have to have a little bit <strong>of</strong> a<br />

social worker in you—you step out <strong>of</strong> a straight lawyer<br />

or straight judge role. <strong>The</strong> task is more complex, much<br />

broader than looking up sentencing guidelines.”<br />

In particular, judges in this area must be willing to take<br />

risks. “<strong>The</strong> hardest cases to decide are those involving<br />

younger juveniles who’ve committed an act <strong>of</strong> violence or<br />

who’ve been caught with a gun, even if they never used<br />

it. You can’t lock every kid up. You put the best orders<br />

in place. And remember, no one counts the kids who are<br />

released and do just fine. <strong>The</strong> vast majority <strong>of</strong> kids don’t recidivate.”<br />

Indeed, most kids at the Youth Guidance Center<br />

are not repeat <strong>of</strong>fenders: in 2008, the recidivism rate was<br />

only 3 percent.<br />

result, decisions “are harder than they used to be. On a<br />

case-by-case basis, we construct orders that can rehabilitate<br />

a child and improve the child’s opportunities for success.<br />

But no one has the crystal ball; there’s no cookie cutter.<br />

Kids come from very different circumstances.”<br />

Not surprisingly, for lawyers and judges focused on troubled<br />

youth, coping mechanisms are essential. “It helps to<br />

have a good family life,” says Hitchens, whose partner is<br />

Nancy Davis, a civil division judge. <strong>The</strong>y have two daughters.<br />

“Our kids have left the nest, but they were four and<br />

six when I became a judge. I could come home from work<br />

and be so grateful that my kids were healthy and they had<br />

hopes and dreams.” Hitchens also spends time gardening<br />

and fishing.<br />

For Bay Area attorneys who may be learning about <strong>San</strong><br />

<strong>Francisco</strong> youth law for the first time, Hitchens says the<br />

most important service adults can provide these kids is<br />

that <strong>of</strong> a mentor. “An adult mentor helps them focus, gives<br />

them positive ways to use their energy, provides job readiness,<br />

and helps them achieve academically. Any successful<br />

person in the world will tell you they had parent mentors<br />

or a coach or an eleventh-grade math teacher who cared<br />

about them one on one.”<br />

<strong>The</strong> Assistant District Attorney<br />

By way <strong>of</strong> example, Hitchens recalls when a young man<br />

wearing a suit came into her court unannounced a few<br />

years ago and asked to speak with her. “It turns out he<br />

came in to thank me. I had given him a second chance<br />

[when he was younger], and he was on his way to college.”<br />

Yet other cases still haunt her, like the teenage mother who<br />

had committed violence. Hitchens chose to place the girl<br />

and her child in a safe, appropriate place. <strong>The</strong> Court <strong>of</strong><br />

Appeal overruled Hitchens and the girl was sent to adult<br />

court. “She hooked up with tough folks,” Hitchens recalls.<br />

“She was rearrested and ended up abandoning her child.”<br />

Today, more kids with weapons and more kids committing<br />

robberies are winding up in Hitchens’s court. As a<br />

18 FALL 2009<br />

Rani Singh

When District Attorney Kamala Harris was looking for<br />

someone to handle juvenile gun cases after receiving a<br />

grant in 2005, Rani Singh threw up her hand.<br />

“I have always been interested in juvenile work,” explains<br />

Singh, who had been handling felony domestic violence<br />

and stalking cases in adult court. “I was a sociology major<br />

with an emphasis in juvenile justice and had even considered<br />

getting a master’s in social work.”<br />

Today, Singh is one <strong>of</strong> six assistant district attorneys who<br />

work with juveniles. She is the assigned DA for the collaborative<br />

courts, and her specialties include gun and serious<br />

sex crimes cases.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Public Defender<br />

Representing youth in delinquency<br />

court requires public<br />

defenders to get involved in a<br />

host <strong>of</strong> “collateral” issues, says<br />

Patricia Lee, <strong>of</strong> the <strong>San</strong> <strong>Francisco</strong><br />

Office <strong>of</strong> the Public Defender,<br />

which represents 1,400<br />

youth a year, some as young as<br />

eleven. Lee, the managing attorney,<br />

oversees a staff <strong>of</strong> seventeen<br />

in the juvenile unit, including seven attorneys.<br />

Unlike adult court, the juvenile court operates on a rehabilitation<br />

model rather than a punishment model, says<br />

Singh, who handles about one hundred files at a time.<br />

Plus, she adds, “it’s much more collaborative than adult<br />

court. I’m getting involved with parents even though I’m<br />

a DA.” Singh says kids in delinquency court have even<br />

called her personally before a hearing to admit, “I’m not<br />

clean.” In adult court, in contrast, Singh “never personalized<br />

the defendants. I never looked at them.”<br />

A mother <strong>of</strong> two young children and a native <strong>San</strong> Franciscan,<br />

Singh believes that DAs who want to work in juvenile<br />

court need to have a sixth sense. “Some kids, you know<br />

you’ll see later in adult court,” she explains, noting factors<br />

like the severity <strong>of</strong> the crime, the age they enter the system,<br />

the family structure, and collateral problems like school,<br />

gang, or drug issues. “Other times, you see the kid and you<br />

know they’ll never come back.”<br />

Singh is married to a deputy sheriff, and their two sometimes<br />

“icky jobs” make them realize how lucky they are—<br />

and how important parents are. Singh recalls a mother<br />

who reeked <strong>of</strong> marijuana in a courtroom, yet yelled at<br />

her. “‘Why are you locking up my baby’ Doing this work<br />

makes me sad and grateful. It makes me angry at parents,”<br />

Singh says.<br />

Yet while some DAs hate doing juvenile work, Singh<br />

doesn’t. “If I see one success story in ten, that’s great because<br />

in adult court, I saw no success.”<br />

Patricia Lee<br />

Collateral issues include educational proceedings like<br />

expulsion and individualized education plans. “We know<br />

the importance <strong>of</strong> keeping kids in school. Many kids<br />

are not bad kids but simply failures <strong>of</strong> the school system.<br />

Many are special education or have mental or behavior<br />

health issues,” Lee explains. “We’ve approached<br />

the problems holistically. Success can be measured by<br />

THE BAR ASSOCIATION OF SAN FRANCISCO SAN FRANCISCO ATTORNEY 19

ecidivism, but also by the<br />

right school placement.”<br />

Many <strong>of</strong> the public defender’s<br />

clients are at the Youth Guidance<br />

Center, a short-term<br />

youth detention facility that<br />

provides residential services<br />

for 132 youth. Those kids are<br />

in custody awaiting investigative<br />

action immediately after<br />

admission, in custody per court order pending further<br />

court hearings, or in custody awaiting placement. Kids<br />

at the YGC receive educational, medical, and mental<br />

health services as well as socialization skills training and<br />

general counseling.<br />

Because some youth wind up on probation for several<br />

years, Lee and her staff get to know them and their complicated<br />

issues. “We don’t just defend. We help them get<br />

guardianship, relocate, find tutoring services.”<br />

She’s also observed an increase in territorial or “turf” issues.<br />

“When the city had it’s backpack giveaway, one giveaway<br />

location had to be up a hill and then we had to provide a<br />

separate giveaway down the hill” because the kids wouldn’t<br />

travel even short distances through areas inhabited by<br />

rival gangs.<br />

Despite the institutional obstacles and emotional challenges<br />

<strong>of</strong> defending delinquent youth, Lee firmly believes<br />

every child should be afforded an opportunity. “Most<br />

youth who come through here don’t know what opportunity<br />

means. If we save one child in a year, that’s the reward<br />

for working in the juvenile justice system. We give them<br />

tools and opportunities to move out <strong>of</strong> the system. Ten<br />

percent are hard core and will move into the adult system.<br />

But first-time <strong>of</strong>fenders A lot <strong>of</strong> these kids will succeed.<br />

We’ve had kids go on to college. To be part <strong>of</strong> that process,<br />

that’s the reward.”<br />

<strong>The</strong> Court Administrator<br />

According to Lee, few public defenders provide the level <strong>of</strong><br />

representation to youth that <strong>San</strong> <strong>Francisco</strong>’s does. “Many<br />

kids in other jurisdictions joke about ‘public pretenders’<br />

or ‘public <strong>of</strong>fenders.’ But we don’t hear that,” she says.<br />

“We’ve developed a level <strong>of</strong> credibility within the system<br />

and community.”<br />

<strong>The</strong> mother <strong>of</strong> four daughters, Lee joined the public defender’s<br />

<strong>of</strong>fice in 1985. She began her career focusing on<br />

gender differences and found that more resources were allocated<br />

to boys in the system. Now more services are devoted<br />

to girls, which is fortunate because the majority <strong>of</strong><br />

girls—as many as 90 percent—have suffered sexual abuse,<br />

abandonment, neglect, mental health, or behavioral issues,<br />

Lee says.<br />

Other changes that Lee has witnessed include fewer crack<br />

cases, but a surge in violent crimes—robberies, weapons<br />

possessions, shootings—by “teenage boys from the poorest<br />

<strong>of</strong> poor communities,” Lee says. “<strong>The</strong>y’re raised by family<br />

members because their fathers are in jail, are in prison, are<br />

deceased, or have been killed. <strong>The</strong>se boys don’t expect to<br />

live past age twenty. We have a high level <strong>of</strong> young people<br />

with serious mental health issues and cognitive deficiencies,<br />

especially those from drug-addicted mothers.”<br />

Claire Williams<br />

20 FALL 2009

<strong>The</strong> main premise <strong>of</strong> <strong>San</strong> <strong>Francisco</strong>’s Unified Family Court<br />

is to deal with families, not individual cases, explains Claire<br />

Williams, the court’s administrative director.<br />

Before unification, a situation might occur in which parental<br />

rights would be terminated in a dependency case;<br />

but if the child later faced criminal charges, the delinquency<br />

court judge, unaware <strong>of</strong> the dependency case, might<br />

release the child back to that parent. Today, however, cross<br />

cases are flagged. At the very least, each judge dealing with<br />

the family now knows about what the other judge is doing.<br />

“We’re headed to one judge, one family: no matter what<br />

door the child came through, the judge would keep the<br />

case,” Williams says. “We’re still working on that. It’s baby<br />

steps.” In the meantime, the judges talk to each other and<br />

to relevant agencies on an as-needed basis. Standing orders<br />

are in place allowing attorneys to communicate.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Public Interest<br />

Lawyer<br />

Public interest attorneys representing<br />

youth <strong>of</strong>ten have to<br />

shift their legal practices to<br />

respond to community needs.<br />

Case in point: a year-old city<br />

policy established by the mayor’s<br />

<strong>of</strong>fice requires that any<br />

undocumented minor who is<br />

booked—not charged—with a<br />

felony must be reported to immigration. Since last July,<br />

130 youth have been reported, resulting in an “onslaught”<br />

<strong>of</strong> cases for Legal Services for Children (LSC), a nonpr<strong>of</strong>it<br />

agency providing legal services to disadvantaged youth,<br />

says director Abigail Trillin.<br />

Another goal is to create consistency and efficiencies across<br />

court orders. “We don’t want the family to have to do one<br />

thing in one system and another thing in another system.”<br />

A former family law lawyer, Williams found herself<br />

“burned out” with family law practice, largely because<br />

she wasn’t good at setting boundaries. “Families will<br />

continue to have problems after representation,” she explains.<br />

“You’re not a knight in shining armor—and you<br />

have to know you’re not or else you’ll take on too<br />

much responsibility.”<br />

Today, most <strong>of</strong> Williams’s work at the court deals with<br />

programs—specifically, finding grants and then overseeing<br />

the administration. She also serves as a liaison to the bench<br />

for dealing with outside agencies. “My job is extremely<br />

collaborative,” says Williams, who has five managers reporting<br />

to her and has no fewer than twenty-five regularly<br />

scheduled meetings. “We’re fortunate in <strong>San</strong> <strong>Francisco</strong>.<br />

We have a fabulous group <strong>of</strong> attorneys, an extremely committed<br />

bar.”<br />

Lawyers who work on youth cases need to be flexible, she<br />

adds. “It’s quasi social work. Lawyers must be empathetic<br />

and understand the bigger picture: how best to create a<br />

resolution that the child and the family can live with.”<br />

Attorneys in this area who are “strict and formal” are too<br />

short sighted, she says. “<strong>The</strong>y may win the battle today,<br />

but you need to look down the road. You can’t look at the<br />

child in a vacuum.”<br />

Abigail Trillin<br />

THE BAR ASSOCIATION OF SAN FRANCISCO SAN FRANCISCO ATTORNEY 21<br />

Photo by Lorraine Lee Nelsen

This immigration rule is so<br />

broad, according to Trillin, that<br />

it includes youth who’ve lived in<br />

the United States “forever” with<br />

their parents. “<strong>The</strong>y’re facing<br />

deportation to countries they<br />

don’t consider their home,” she<br />

says. In many cases, “they don’t<br />

even speak the language.”<br />

As a result, LSC has shifted its<br />

focus to assist immigrant youth<br />

in federal detention. If they’ve committed a minor <strong>of</strong>fense,<br />

they’re sent to the Office <strong>of</strong> Refugee Resettlement, an arm<br />

<strong>of</strong> the U.S. Department <strong>of</strong> Health and Human Services.<br />

<strong>The</strong> level <strong>of</strong> placement—a shelter, a staff-secure facility or<br />

juvenile hall—depends on the child’s age and the charges.<br />

Children charged with major <strong>of</strong>fenses are put directly in<br />

the custody <strong>of</strong> U.S. Immigration Services.<br />

LSC helps families reunite while cases are pending and<br />

also lobbies for lower placement, explains Trillin, who has<br />

worked at LSC for thirteen years.<br />

“This is devastating the lives <strong>of</strong> many families,” she says.<br />

“It also undermines the neutrality and confidentiality <strong>of</strong><br />

the system.”<br />

Now unauthorized individuals are looking at otherwise<br />

confidential juvenile files, and youth are being charged<br />

with felonies for otherwise minor violations like graffiti,<br />

Trillin says. “This policy undermines the work <strong>of</strong> the court<br />

to rehabilitate and, frankly, undermines public safety in<br />

our city. Now immigrant youth are more isolated and<br />

more likely to commit crimes. A graffiti charge is a very<br />

solvable case: they used to be able go into the public art<br />

program and do murals.”<br />

Especially troubling for Trillin is that the mounting immigration<br />

cases take her staff away from other pro bono<br />

work they could be doing.<br />

Founded in 1975 as one <strong>of</strong> country’s first nonpr<strong>of</strong>it law<br />

firms devoted to youth, LSC provides multidisciplinary,<br />

holistic advocacy with social worker–attorney teams. Although<br />

it doesn’t practice in delinquency court, LSC handles<br />

legal issues regarding dependency, education, guardianship,<br />

and immigration. It also <strong>of</strong>fers an advice line and<br />

drop-in clinics.<br />

Last year, LSC provided counsel to 121 youth in dependency<br />

court and helped 288 youth avoid foster care by<br />

establishing guardianships. <strong>The</strong> organization is funded by<br />

county money, foundations, grants, individual giving, and<br />

some court fees.<br />

A former teacher <strong>of</strong> bilingual third graders, Trillin now<br />

manages LSC’s social workers and seven attorneys as well<br />

as the two hundred lawyers on a pro bono panel. Everyone<br />

on her team is either a “closet social worker or a closet<br />

lawyer,” she quips. “<strong>The</strong>y have an interest in both areas.<br />

Family problems are complex and are rarely solved by a<br />

legal solution only.”<br />

For the kids, the process <strong>of</strong> receiving good representation<br />

is “really powerful for them,” Trillin adds. “Even in cases<br />

when they lose, they learn that a person believes in them.<br />

And for the lawyer, the work is incredibly rewarding.”<br />

LSC’s model, Trillin adds, is to be the attorneys for the minor—not<br />

the guardian ad litem. “<strong>The</strong>y are the client,” she<br />

says. “And people are surprised to hear that young people<br />

need lawyers.”<br />

BASF’s Conflicts Panel<br />

Since the 1970s the juvenile courts, which are a part <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>San</strong> <strong>Francisco</strong>’s Unified Family Court, have looked to <strong>The</strong><br />

<strong>Bar</strong> <strong>Association</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>San</strong> <strong>Francisco</strong>’s Lawyer Referral and Information<br />

Service Conflicts Panel to provide qualified and<br />

experienced lawyers to represent minors that cannot be<br />

represented by the public defender because <strong>of</strong> a conflict <strong>of</strong><br />

interest. Panel attorneys, like their public defender counterparts,<br />

must be knowledgeable about public and private<br />

resources, for each minor presents a myriad <strong>of</strong> problems<br />

that have led him or her to juvenile court.<br />

<strong>The</strong> panel attorney not only defends the criminal charge<br />

but also acts as an advocate in special education proceedings,<br />

school expulsion hearings, and program placement.<br />

Panel attorneys access social workers, mental health consultants,<br />

community-based programs, and other resources<br />

necessary for a holistic representation <strong>of</strong> their clients.<br />

22 FALL 2009

Some attorneys form relationships with their young clients<br />

that may last into adulthood.<br />

Three members <strong>of</strong> BASF’s Conflicts Panel, Lisa Dewberry,<br />

Joseph Tomsic, and Ruth Edelstein represent a cross-section<br />

<strong>of</strong> the panel and its experience.<br />

Lisa Dewberry<br />

Lisa Dewberry<br />

“It’s the autonomy I like,” reports Lisa Dewberry. As a former<br />

public defender and former supervising attorney for<br />

the public defender’s juvenile division, Dewberry’s practice<br />

has spanned both public and private <strong>of</strong>fices. “I’m not<br />

subjected to any policy considerations <strong>of</strong> a government <strong>of</strong>fice;<br />

my practice, my resources, my experience, and what I<br />

bring to each case have expanded dramatically by virtue <strong>of</strong><br />

a private practice.” <strong>The</strong>re is camaraderie and a sharing <strong>of</strong><br />

experience broader than the support <strong>of</strong>fered by the public<br />

defender, for Dewberry practices in multiple jurisdictions,<br />

gaining experience, insight, and a longer list <strong>of</strong> experts<br />

and consultants to add to her already remarkable experience<br />

during twenty-nine years, including twenty-three as<br />

a public defender.<br />

Though Dewberry’s caseload includes adults in the criminal<br />

courts, the draw to work with youth is a strong one.<br />

“We are so much more creative in our approach with<br />

youth. We have real impact on the outcome for many <strong>of</strong><br />

these juveniles for we must do<br />

more than defend the charges;<br />

we work hard to shape futures<br />

by presenting the court with<br />

workable options.”<br />

Too <strong>of</strong>ten the court is the only<br />

“safety net” available to these<br />

youth. Dewberry <strong>of</strong>fers an example<br />

<strong>of</strong> a young client who<br />

faced robbery charges. His<br />

mother, a crack addict, lost parental<br />

rights by court order. With no one to care for him,<br />

he found himself in the care <strong>of</strong> a stranger who not only<br />

used him sexually but, “to earn his keep,” instructed him<br />

how to commit strong-arm robberies. Although the case<br />

was factually difficult to defend, “I convinced the prosecutor<br />

to keep the case at YGC instead <strong>of</strong> sending this kid<br />

downtown to be prosecuted as an adult; we not only found<br />

real program support for this kid, the psychological evaluation<br />

was so compelling that the two prosecutors were<br />

clearly moved and became role models, letting this kid<br />

know that they cared about him—that they cared about<br />

his future. Sure, he has to be accountable, but what’s so<br />

interesting about juvenile practice is that the very same<br />

people who are prosecuting can actually play a therapeutic<br />

role given the collaboration possible only at YGC.”<br />

Joseph Tomsic<br />

Joe Tomsic is a private practitioner specializing in juvenile<br />

law and a member <strong>of</strong> BASF’s Conflicts Panel since 1991.<br />

His private practice takes him to Marin, <strong>San</strong> Mateo, Sonoma,<br />

and <strong>San</strong>ta Clara, but Tomsic finds that <strong>San</strong> Fran-<br />

Joseph Tomsic<br />

Photo courtesy <strong>of</strong> Joseph Tomsic

cisco’s juvenile court—unlike<br />

those in neighboring counties—<br />

creates an atmosphere conducive<br />

to collaboration. “This collaborative<br />

approach makes the<br />

work here highly productive;<br />

here, attorneys have ready access<br />

to probation <strong>of</strong>ficers, district attorneys,<br />

and bench <strong>of</strong>ficers. This<br />

facilitates, rather than frustrates<br />

the goals <strong>of</strong> the work.”<br />

Tomsic finds that not only do panel attorneys share the<br />

same passion for this work but they also are a highly skilled<br />

group. “Panel attorneys know what they’re doing; we must<br />

apply regularly to do panel work, hone and improve our<br />

skills constantly, all <strong>of</strong> which is reviewed regularly. We are<br />

not members <strong>of</strong> an agency or <strong>of</strong>fice where it’s difficult to<br />

get fired.” According to Tomsic, attorneys who practice at<br />

YGC are a tight-knit group and regularly exchange and<br />

discuss ideas, research, pleadings, and experience. Practice<br />

at YCG has been and remains a perfect fit for Joe Tomsic.<br />

Ruth Edelstein<br />

Former public defender, former city attorney with seven<br />

years <strong>of</strong> private practice sandwiched in between, Ruth<br />

Edelstein returned to private practice in 2004 and is highly<br />

regarded at YGC, the Hall <strong>of</strong> Justice, and dependency<br />

departments. Her clients, <strong>of</strong>ten accused <strong>of</strong> the most serious<br />

crimes in adult and juvenile court, have also included<br />

parents and children in the dependency system. Her<br />

experience as a city attorney representing social workers<br />

in dependency proceedings provided the additional background<br />

unique to dependency court. In short, there’s<br />

almost no aspect <strong>of</strong> juvenile work that Edelstein<br />

“doesn’t get.”<br />

Edelstein finds that working with youth is far more compelling<br />

than adults. “Kids need and are open to relationships<br />

with caring adults; they are truly looking for a way<br />

to connect and this permits the practitioner a window <strong>of</strong><br />

opportunity to impact kids’ lives; relationships make the<br />

critical difference.”<br />

As a private attorney, “I have more time to develop these<br />

relationships than I did when I ran a calendar in a courtroom.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re’s a freedom to connect, really connect, that’s<br />

unique to private practice and highly rewarding.”<br />

<strong>The</strong> stakes in criminal prosecutions are extraordinarily<br />

high, and “if we can save our youth from the adult system,<br />

we’ve done our job.” Kids make incredible mistakes,<br />

rarely able to calculate the risks or consequences <strong>of</strong> their<br />

actions given their developmental limitations. As a result,<br />

many face a lifetime in prison if they reach adult court.<br />

<strong>The</strong>refore, keeping them in the juvenile system while they<br />

mature is paramount to the work <strong>of</strong> the juvenile practitioner.<br />

“Our job is to know our clients and advocate that each<br />

child is a valuable human being, capable <strong>of</strong> change, deserving<br />

to be saved from a lifetime <strong>of</strong> incarceration.”<br />

A former lawyer, Leslie A. Gordon is a freelance legal journalist<br />

living in <strong>San</strong> <strong>Francisco</strong>. She can be reached at leslie.<br />

gordon@stanfordalumni.org.<br />

Julie Traun, a private practitioner and attorney administrator<br />

for BASF’s Lawyer Referral and Information Service’s Indigent<br />

Defense Administration, assisted with this article.<br />

Ruth Edelstein<br />

24 FALL 2009