China's growing role in African peace and security - Saferworld

China's growing role in African peace and security - Saferworld

China's growing role in African peace and security - Saferworld

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

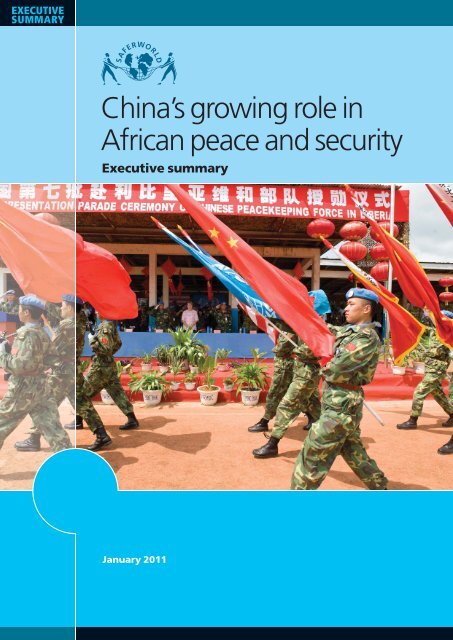

EXECUTIVE<br />

SUMMARY<br />

Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s <strong>grow<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>role</strong> <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>African</strong> <strong>peace</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>security</strong><br />

Executive summary<br />

January 2011

Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s <strong>grow<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>role</strong> <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>African</strong> <strong>peace</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>security</strong><br />

Executive summary<br />

SAFERWORLD<br />

january 2011

© <strong>Saferworld</strong>, January 2011. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be<br />

reproduced, stored <strong>in</strong> a retrieval system or transmitted <strong>in</strong> any form or by any means<br />

electronic, mechanical, photocopy<strong>in</strong>g, record<strong>in</strong>g or otherwise, without full attribution.<br />

<strong>Saferworld</strong> welcomes <strong>and</strong> encourages the utilisation <strong>and</strong> dissem<strong>in</strong>ation of the material<br />

<strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> this publication. Please contact <strong>Saferworld</strong> if you would like to translate<br />

this report.

i<br />

Executive summary<br />

c h i n a ’s e n g a g e m e n t w i t h a f r i c a has deepened substantially over the past<br />

decade. For <strong>African</strong> nations, this engagement presents both opportunities <strong>and</strong><br />

challenges at a critical conjuncture <strong>in</strong> the cont<strong>in</strong>ent’s history. This report critically<br />

assesses Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s <strong>grow<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>role</strong> <strong>in</strong> Africa <strong>and</strong> its effect on both the factors that drive<br />

conflict <strong>and</strong> those that promote <strong>peace</strong>. With 54 nations <strong>and</strong> one billion people, the<br />

<strong>African</strong> cont<strong>in</strong>ent is far from a homogenous unit of analysis. Its <strong>security</strong> challenges<br />

are numerous <strong>and</strong> varied, <strong>and</strong> as such it is not possible to form an all-encompass<strong>in</strong>g<br />

assessment of the way <strong>in</strong> which Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s engagement on the cont<strong>in</strong>ent affects these<br />

challenges. Instead, the report takes a thematic approach, look<strong>in</strong>g at a number of<br />

topics: Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s bilateral relations with <strong>African</strong> states; its military co-operation with<br />

their armed forces; the Ch<strong>in</strong>a-Africa arms trade; Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s relations with <strong>African</strong><br />

regional organisations; its <strong>in</strong>volvement <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternational co-operation; Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s <strong>role</strong> <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>peace</strong>keep<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> <strong>peace</strong>build<strong>in</strong>g; <strong>and</strong> its economic engagements on the cont<strong>in</strong>ent.<br />

The report draws on a wide spectrum of views <strong>and</strong> perspectives from Ch<strong>in</strong>ese, <strong>African</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternational experts. It also makes recommendations for how Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s engagement<br />

can better support the common goal of <strong>peace</strong>, <strong>security</strong> <strong>and</strong> development <strong>in</strong> Africa.<br />

Deepen<strong>in</strong>g relations,<br />

press<strong>in</strong>g challenges<br />

Economic co-operation lies at the forefront of contemporary Ch<strong>in</strong>a-Africa relations.<br />

In just ten years, between 1998 <strong>and</strong> 2008, Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s trade value with Africa grew from<br />

under $6 billion to $107 billion. 1 Natural resources have a prom<strong>in</strong>ent <strong>role</strong> <strong>in</strong> the trade<br />

relationship, but Africa also presents a <strong>grow<strong>in</strong>g</strong> market for Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s own goods <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>vestments. Ch<strong>in</strong>a has committed itself to becom<strong>in</strong>g a development partner for<br />

Africa <strong>and</strong> has started to deliver development assistance. Strategic objectives also have<br />

a place <strong>in</strong> Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s engagement, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g cement<strong>in</strong>g the diplomatic isolation of Taiwan<br />

<strong>and</strong> strengthen<strong>in</strong>g its own <strong>in</strong>ternational position. Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s relations with Africa – often<br />

referred to <strong>in</strong> terms of “south-south co-operation” – are largely managed through<br />

state-to-state bilateral relations. In complement to this, the triennial Forum on Ch<strong>in</strong>a-<br />

Africa Co-operation (FOCAC) provides an important multilateral mechanism for<br />

forg<strong>in</strong>g new commitments <strong>and</strong> strengthen<strong>in</strong>g political ties.<br />

Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s engagement <strong>in</strong> Africa has been welcomed by many <strong>African</strong> leaders, who see<br />

it as an opportunity to fuel economic growth, to put them <strong>in</strong>to a better negotiat<strong>in</strong>g<br />

position with traditional Western donors <strong>and</strong> to amplify Africa’s voice <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternational<br />

forums. At the same time, these leaders face the challenge of captur<strong>in</strong>g the benefits<br />

of the relationship while avoid<strong>in</strong>g some of the pitfalls that have marked Africa’s past<br />

engagement with outside powers. Ch<strong>in</strong>a itself faces challenges <strong>in</strong> better regulat<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

conduct of its commercial actors, improv<strong>in</strong>g its relations with a vocal <strong>African</strong> civil<br />

1 Trade Law Centre for Southern Africa (2010) Trade Data: Ch<strong>in</strong>a-Africa Trade Onl<strong>in</strong>e Database.

ii<br />

c h i n a’ s g r o w i n g r o l e <strong>in</strong> a f r i c a n p e a c e a n d s e c u r i t y<br />

society <strong>and</strong> ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g its image as a develop<strong>in</strong>g-country partner that shares the<br />

same <strong>in</strong>terests as Africa.<br />

One challenge for Ch<strong>in</strong>a-Africa relations is cont<strong>in</strong>ued <strong>in</strong><strong>security</strong> <strong>and</strong> conflict on the<br />

cont<strong>in</strong>ent. It holds only 14 percent of the world’s population but from 1990–2005 Africa<br />

accounted for half of the number of deaths caused by conflict. 2 While <strong>in</strong> recent years<br />

the cont<strong>in</strong>ent has experienced a decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> levels of conflict, a host of factors cont<strong>in</strong>ue<br />

to challenge both the <strong>security</strong> of <strong>African</strong> states <strong>and</strong> the <strong>security</strong> of their citizens,<br />

rang<strong>in</strong>g from ongo<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>surrection to politically motivated violence to armed crime.<br />

Between 1990 <strong>and</strong> 2005, conflict cost <strong>African</strong> countries almost $300 billion – roughly<br />

the same amount as these countries received <strong>in</strong> aid dur<strong>in</strong>g the same period. 3 Clearly, if<br />

development is to be successful <strong>and</strong> lead to a reduction <strong>in</strong> poverty, stakeholders both<br />

with<strong>in</strong> <strong>and</strong> outside the cont<strong>in</strong>ent must f<strong>in</strong>d ways to reduce the <strong>in</strong>cidence of violent<br />

conflict. Solutions to <strong>African</strong> <strong>peace</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>security</strong> threats are to be found primarily<br />

with<strong>in</strong> the cont<strong>in</strong>ent itself, <strong>in</strong> the h<strong>and</strong>s of governments, politicians <strong>and</strong> civil society<br />

who proactively use state <strong>in</strong>stitutions, regional structures <strong>and</strong> activism for <strong>peace</strong>ful<br />

ends. However it would be wrong to assume that Africa’s conflicts are Africa’s problems<br />

alone. The repercussions of Africa’s <strong>in</strong>ternal problems reach beyond its natural borders.<br />

Furthermore, external actors can play direct <strong>role</strong>s <strong>in</strong> the cont<strong>in</strong>ent’s <strong>security</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scape<br />

– with both positive <strong>and</strong> negative ramifications.<br />

Ch<strong>in</strong>a is one such <strong>in</strong>fluential actor. Its <strong>grow<strong>in</strong>g</strong> presence on the cont<strong>in</strong>ent has meant<br />

that it <strong>in</strong>evitably plays a <strong>role</strong> – albeit often <strong>in</strong>direct – <strong>in</strong> some of Africa’s conflicts.<br />

Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s <strong>in</strong>terests have <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly come under threat, plac<strong>in</strong>g its energy <strong>security</strong>,<br />

economic <strong>in</strong>vestments <strong>and</strong> the lives of its citizens at risk. More broadly, Ch<strong>in</strong>a has an<br />

<strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> act<strong>in</strong>g – <strong>and</strong> be<strong>in</strong>g seen to act – as a responsible global power, <strong>and</strong> therefore<br />

one that assists Africa <strong>in</strong> address<strong>in</strong>g its <strong>in</strong>terrelated <strong>peace</strong> <strong>and</strong> development challenges.<br />

Def<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the<br />

boundaries of non<strong>in</strong>terference<br />

S<strong>in</strong>ce the end of the Cold War, Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s bilateral relations with <strong>African</strong> states have<br />

been largely determ<strong>in</strong>ed by the pr<strong>in</strong>ciples of non-<strong>in</strong>terference <strong>and</strong> respect for state<br />

sovereignty. Domestic political affairs are seen as the exclusive concern of national<br />

governments: other states must respect this basic pr<strong>in</strong>ciple no matter the conduct of<br />

the government. Ch<strong>in</strong>a has developed close relationships with <strong>African</strong> regimes that<br />

the <strong>in</strong>ternational community, or more specifically Western countries, only engage<br />

with <strong>in</strong> a manner that is conditional on improvements <strong>in</strong> governance. Ch<strong>in</strong>ese officials<br />

ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> that such improvements must come from with<strong>in</strong> <strong>and</strong> that, <strong>in</strong> order to allow<br />

this to happen, sovereignty must be respected.<br />

Many would agree that good governance cannot be imposed from the outside.<br />

However, through its diplomatic relations <strong>and</strong> <strong>grow<strong>in</strong>g</strong> economic <strong>role</strong> – not to<br />

mention through its co-operation on military affairs <strong>and</strong> trade <strong>in</strong> arms – Ch<strong>in</strong>a already<br />

has an impact on the <strong>in</strong>ternal affairs of many <strong>African</strong> countries. Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s own <strong>in</strong>vestments<br />

are placed at risk when these countries become unstable. In addition, Beij<strong>in</strong>g’s<br />

pr<strong>in</strong>ciple of non-<strong>in</strong>terference has led it to become closely associated with rul<strong>in</strong>g elites<br />

<strong>in</strong> countries with which it has relations. This makes Ch<strong>in</strong>a <strong>and</strong> Ch<strong>in</strong>ese <strong>in</strong>vestments<br />

a target for opposition leaders, civil society activists <strong>and</strong> rebels, some of whom may<br />

come to be power holders themselves. By choos<strong>in</strong>g to ignore the political situation <strong>in</strong><br />

countries <strong>in</strong> which it <strong>in</strong>vests, Ch<strong>in</strong>a places both its <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>and</strong> image at stake.<br />

Dur<strong>in</strong>g periods of violent domestic crisis <strong>in</strong> Africa, Ch<strong>in</strong>ese policy has tended to<br />

recog nise the legitimacy of the relevant government’s position. Because of this, Ch<strong>in</strong>a<br />

has been accused of allow<strong>in</strong>g crises to cont<strong>in</strong>ue. Ch<strong>in</strong>ese officials <strong>and</strong> scholars reject<br />

the proposition that Ch<strong>in</strong>a is a passive actor <strong>and</strong> suggest that <strong>in</strong>stead it has started to<br />

2 Human Security Report Project (2009) Human Security Report 2009 – The Shr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g Costs of War, Vancouver: HSRP.<br />

3 IANSA, Oxfam & <strong>Saferworld</strong> (2007) Africa’s Miss<strong>in</strong>g Billions: International arms flows <strong>and</strong> the cost of armed conflict,<br />

London: IANSA, Oxfam & <strong>Saferworld</strong>.

s a f e r w o r l d iii<br />

use ‘<strong>in</strong>fluence’ to press for a resolution of conflicts. There is some evidence that this is<br />

the case. For example, after 2006, Ch<strong>in</strong>a played an important <strong>role</strong> <strong>in</strong> secur<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Khartoum’s acceptance of the deployment of <strong>peace</strong>keepers <strong>in</strong> Darfur. In late 2008<br />

Ch<strong>in</strong>a actively pushed the governments of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC)<br />

<strong>and</strong> Rw<strong>and</strong>a to resolve the conflict <strong>in</strong> eastern DRC, where Rw<strong>and</strong>a was support<strong>in</strong>g<br />

rebel groups.<br />

Several Ch<strong>in</strong>ese scholars argue that <strong>in</strong> recent years Ch<strong>in</strong>a has become more flexible <strong>in</strong><br />

its <strong>in</strong>terpretation of non-<strong>in</strong>terference <strong>and</strong> is will<strong>in</strong>g to take a more active diplomatic<br />

<strong>role</strong> <strong>in</strong> the resolution of <strong>in</strong>ternal conflicts. This should be strongly welcomed by those<br />

with an <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> Africa’s <strong>peace</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>security</strong>. However, non-<strong>in</strong>terference <strong>and</strong><br />

sovereignty will rema<strong>in</strong> at the core of Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s engagement <strong>and</strong> any policy changes to<br />

their <strong>in</strong>terpretation will be gradual, cautious <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> many cases restricted to ad hoc<br />

responses to specific contexts. Ch<strong>in</strong>a has little experience of engag<strong>in</strong>g on conflicts<br />

overseas <strong>and</strong> rema<strong>in</strong>s reluctant to take the lead. More generally Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s bilateral<br />

<strong>in</strong>fluence should not be overemphasised: it cannot magically solve conflicts alone.<br />

But as Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s presence <strong>in</strong> Africa <strong>in</strong>creases, Beij<strong>in</strong>g should prepare for the fact that <strong>in</strong><br />

many cases it will be expected to play a major <strong>role</strong>. It should do so more regularly if it<br />

seeks to prove that it is not a passive actor <strong>in</strong> the face of ongo<strong>in</strong>g conflicts <strong>and</strong> human<br />

suffer<strong>in</strong>g. Policy focus could also be placed on how Ch<strong>in</strong>a can move beyond crisis<br />

reaction to more proactive conflict prevention. Sudan, where at the time of writ<strong>in</strong>g<br />

tensions are mount<strong>in</strong>g between the North <strong>and</strong> the South, presents a specific case<br />

where this will prove to be the less costly option for Ch<strong>in</strong>a <strong>in</strong> the long term.<br />

Ultimately, Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s impact on a given country is determ<strong>in</strong>ed by how its leaders choose<br />

to utilise Ch<strong>in</strong>ese support. <strong>African</strong> governments <strong>and</strong> civil society hold the key to both<br />

improv<strong>in</strong>g governance <strong>in</strong> their countries <strong>and</strong> to hold<strong>in</strong>g Ch<strong>in</strong>a to account. However,<br />

Ch<strong>in</strong>ese policy makers need to be more sensitive to the impact of Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s engagement<br />

<strong>in</strong> Africa’s <strong>in</strong>ternal affairs. While Beij<strong>in</strong>g is unlikely to start push<strong>in</strong>g for a political<br />

reform agenda as part of its state-to-state relations, better dist<strong>in</strong>guish<strong>in</strong>g between the<br />

<strong>in</strong>terests of regimes <strong>and</strong> those of their citizens will ultimately serve its long-term<br />

<strong>in</strong>terests. For their part, Western states need to avoid s<strong>in</strong>gl<strong>in</strong>g out for criticism Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s<br />

relations with problematic <strong>African</strong> regimes – unless they can also acknowledge that<br />

they have very often acted similarly. Failure to do so feeds <strong>in</strong>to Ch<strong>in</strong>ese fears that the<br />

foundation of Western criticism is geopolitical. Greater levels of dialogue <strong>and</strong> engagement<br />

with Beij<strong>in</strong>g on what are very often shared concerns – for both <strong>in</strong>ternal <strong>and</strong><br />

other external stakeholders <strong>in</strong> Africa – could help to resolve what is a complex web of<br />

differ<strong>in</strong>g perspectives, normative judgements <strong>and</strong> national <strong>in</strong>terests.<br />

Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s military<br />

co-operation <strong>in</strong> Africa<br />

Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s military co-operation is modest compared to its wider engagements <strong>in</strong> Africa,<br />

<strong>and</strong> it is primarily used to strengthen political ties with <strong>African</strong> governments. It is<br />

facilitated through high-level political delegations, military exchanges <strong>and</strong> defence<br />

attachés based <strong>in</strong> embassies. The content of military co-operation varies from country<br />

to country, but <strong>in</strong>cludes f<strong>in</strong>ancial assistance for military <strong>in</strong>frastructure, de-m<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g<br />

support <strong>and</strong> tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g for <strong>African</strong> armed forces. Although Ch<strong>in</strong>a has contributed to<br />

<strong>peace</strong>keep<strong>in</strong>g operations <strong>in</strong> Africa <strong>and</strong> participates <strong>in</strong> anti-piracy efforts <strong>in</strong> the Gulf<br />

of Aden, it ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>s no permanent military presence on the cont<strong>in</strong>ent.<br />

That Ch<strong>in</strong>a has committed to support<strong>in</strong>g <strong>African</strong> militaries to develop their <strong>peace</strong>keep<strong>in</strong>g<br />

capabilities <strong>and</strong> given assistance to de-m<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g operations is positive <strong>and</strong><br />

should cont<strong>in</strong>ue. On the other h<strong>and</strong>, given the secrecy surround<strong>in</strong>g the extent of<br />

Ch<strong>in</strong>ese-<strong>African</strong> military co-operation, it is difficult to fully assess its impact on<br />

<strong>African</strong> <strong>peace</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>security</strong>. This lack of transparency may re<strong>in</strong>force problems related<br />

to the civilian accountability of <strong>African</strong> armed forces. A serious challenge for all<br />

external actors is that while <strong>African</strong> <strong>security</strong> might be improved by provid<strong>in</strong>g tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g<br />

to militaries, these very militaries are often themselves obstacles to <strong>security</strong>. In Gu<strong>in</strong>ea,

iv<br />

c h i n a’ s g r o w i n g r o l e <strong>in</strong> a f r i c a n p e a c e a n d s e c u r i t y<br />

Ch<strong>in</strong>ese-tra<strong>in</strong>ed comm<strong>and</strong>os were <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> the kill<strong>in</strong>g of 150 protesters <strong>in</strong> 2009,<br />

while the national armed forces of the DRC – to which Ch<strong>in</strong>a has also provided<br />

tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g – have been accused of various violations of <strong>in</strong>ternational humanitarian law. 4<br />

These are <strong>in</strong> fact challenges faced by all external actors. For example, American <strong>and</strong><br />

French tra<strong>in</strong>ed units were also implicated <strong>in</strong> the events <strong>in</strong> Gu<strong>in</strong>ea <strong>in</strong> 2009 <strong>and</strong> several<br />

countries provide military assistance to the national army <strong>in</strong> the DRC. Greater levels<br />

of co-operation between external actors would help resolve some of the problems they<br />

face <strong>and</strong> make assistance more effective. Ch<strong>in</strong>a itself should ensure that the pr<strong>in</strong>ciples<br />

of civilian protection <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternational humanitarian law are a significant component<br />

of its tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g. Military assistance is most effective when it supports the emergence of<br />

armed forces that are accountable to civilian oversight, delivered as part of a holistic<br />

process of <strong>security</strong> sector development. <strong>African</strong> policy makers <strong>and</strong> civil society should<br />

ensure that military co-operation with Ch<strong>in</strong>a is congruent with these wider processes.<br />

End-users <strong>and</strong> the<br />

impact of Ch<strong>in</strong>ese arms<br />

The paucity of reliable data <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation makes it difficult to provide a completely<br />

accurate <strong>and</strong> comprehensive picture of Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s arms transfers to Africa. Although<br />

Ch<strong>in</strong>a rema<strong>in</strong>s a modest player <strong>in</strong> the global arms market, between 2006 <strong>and</strong> 2009<br />

over 98 percent of its exports went to the develop<strong>in</strong>g world. 5 In fact, accord<strong>in</strong>g to some<br />

estimates, Ch<strong>in</strong>a was the s<strong>in</strong>gle largest arms exporter to sub-Saharan Africa dur<strong>in</strong>g<br />

this period, provid<strong>in</strong>g a wide range of conventional weapons to a large number of<br />

states. 6 Ch<strong>in</strong>a is a particularly large supplier of small arms <strong>and</strong> light weapons (SALW). 7<br />

Africa is seen as a <strong>grow<strong>in</strong>g</strong> market for Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s state-owned but commercially focused<br />

defence <strong>in</strong>dustry. Ch<strong>in</strong>a presents a source of affordable weapons for <strong>African</strong> militaries,<br />

while for some it is a viable alternative to Western states that refuse to supply them.<br />

More broadly, Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s arms agreements with <strong>African</strong> states are used to cement political<br />

ties as part of its wider diplomacy.<br />

The challenge with Ch<strong>in</strong>ese arms exports lies with how some of these weapons are<br />

used <strong>and</strong> the h<strong>and</strong>s <strong>in</strong> which they end up. Ch<strong>in</strong>ese arms, utilised responsibly by<br />

legitimate <strong>and</strong> accountable police forces, militaries or <strong>peace</strong>keepers, can serve to<br />

improve <strong>security</strong>. At the same time, <strong>in</strong> several contexts Ch<strong>in</strong>ese-made weapons <strong>and</strong><br />

ammunition are likely to have worsened conflict <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong><strong>security</strong>. For example, Ch<strong>in</strong>ese<br />

weapons have been used <strong>in</strong> Sudan to commit violations of human rights <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternational<br />

humanitarian law by government forces, militias <strong>and</strong> rebel groups. 8 Furthermore,<br />

Ch<strong>in</strong>a has cont<strong>in</strong>ued to supply Khartoum despite the Sudanese Government’s<br />

persistent violations of a United Nations (UN) arms embargo on Darfur.<br />

Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s arms trade came under the spotlight <strong>in</strong> April 2008 when a Ch<strong>in</strong>ese vessel tried<br />

to deliver to Zimbabwe significant quantities of weapons dur<strong>in</strong>g a period of violent<br />

<strong>in</strong>ternal unrest. 9 While the shipment was recalled <strong>and</strong> justified as a case of mistaken<br />

tim<strong>in</strong>g, Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s image as a responsible global actor was tarnished. Supplies to Zimbabwe<br />

have played a facilitat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>role</strong> <strong>in</strong> allow<strong>in</strong>g the government to suppress opposition <strong>and</strong><br />

hang on to state power. Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s regulations govern<strong>in</strong>g arms transfers state that they<br />

should not <strong>in</strong>terfere <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>ternal affairs of recipients. However, if arms transfers<br />

contribute to underm<strong>in</strong>e stability, or facilitate human rights violations, one could well<br />

argue that such transfers do <strong>in</strong>terfere <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>ternal affairs of recipient countries.<br />

4 Amnesty International (2010) Gu<strong>in</strong>ea: You did not want the military, so now we are go<strong>in</strong>g to teach you a lesson – The events<br />

of 28 September 2009 <strong>and</strong> their aftermath, London: Amnesty International, p 32; United Nations Security Council (2009)<br />

F<strong>in</strong>al Report of the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of Congo United Nations Report S/2009/603.<br />

5 Grimmett, Richard F (2010), Conventional Arms Transfers to Develop<strong>in</strong>g Nations, 2002–2009, United States Congressional<br />

Research Service, p 32.<br />

6 Ibid.<br />

7 Small Arms Survey (2009) Small Arms Survey 2009: Shadows of war, Oxford: Oxford University Press, p 24.<br />

8 Amnesty International (2006) Ch<strong>in</strong>a: Susta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g Conflict <strong>and</strong> Human Rights Abuses: The Flow of Arms Cont<strong>in</strong>ues.<br />

9 Spiegel, Samuel J & Le Billon, Philippe (2009) ‘Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s weapons trade: from ships of shame to the ethics of global resistance’<br />

<strong>in</strong> International Affairs, vol. 85:2, pp 323–346.

s a f e r w o r l d v<br />

While Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s arms regulations oppose the re-transfer of weapons <strong>and</strong> the supply of<br />

weapons to non-state actors, lax risk assessments <strong>and</strong> monitor<strong>in</strong>g mechanisms mean<br />

that they have at times been diverted <strong>and</strong> ended up <strong>in</strong> the wrong h<strong>and</strong>s. For example,<br />

<strong>in</strong> the DRC Ch<strong>in</strong>ese-made weapons are commonly found among rebel groups. 10<br />

Weapons deals are often shrouded <strong>in</strong> secrecy, mak<strong>in</strong>g it difficult to track supply <strong>and</strong><br />

disrupt illegal arms supply cha<strong>in</strong>s. Although Ch<strong>in</strong>a has made commitments with<strong>in</strong><br />

FOCAC to assist <strong>African</strong> efforts to help tackle the illicit trade <strong>in</strong> SALW, these have yet<br />

to materialise on the ground.<br />

Policy makers <strong>and</strong> scholars <strong>in</strong> Ch<strong>in</strong>a are <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly aware of the problems <strong>and</strong><br />

contradictions of Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s arms transfers. While the responsibility for their end-use<br />

lies primarily with recipient states, Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s policy makers need to start better assess<strong>in</strong>g<br />

the risks associated with end-use of arms when mak<strong>in</strong>g transfer decisions <strong>and</strong> work to<br />

improve transparency <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation shar<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Ch<strong>in</strong>a is hardly alone <strong>in</strong> transferr<strong>in</strong>g arms that are eventually used <strong>in</strong> <strong>African</strong> conflicts.<br />

Most of the <strong>African</strong> countries that have received arms from Ch<strong>in</strong>a have also received<br />

arms from the other major exporters. Any critical engagement with Ch<strong>in</strong>a needs to<br />

reflect a nuanced underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g of the responsibility of all key actors <strong>and</strong> a will<strong>in</strong>gness<br />

to address the problem collectively. The Arms Trade Treaty (ATT) discussions at the<br />

UN present a real opportunity to take this next step.<br />

The regional l<strong>and</strong>scape<br />

The multilateral political l<strong>and</strong>scape of Africa has seen many changes over the past<br />

decade with the <strong>African</strong> Union (AU) <strong>and</strong> sub-regional organisations play<strong>in</strong>g a larger<br />

<strong>role</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>peace</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>security</strong> issues. The AU’s Peace <strong>and</strong> Security Council (PSC) <strong>and</strong> the<br />

Africa St<strong>and</strong>by Force (ASF) allow it to more actively engage <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>tervene to prevent<br />

or resolve conflicts <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong><strong>security</strong>. It has deployed <strong>peace</strong>keepers <strong>in</strong> Burundi, Somalia<br />

<strong>and</strong> Sudan <strong>and</strong> has taken diplomatic measures <strong>in</strong> response to various other conflicts.<br />

Sub-regional organisations have been equally active <strong>in</strong> <strong>peace</strong>keep<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> diplomatic<br />

efforts, as well as creat<strong>in</strong>g early warn<strong>in</strong>g systems <strong>and</strong> measures to prevent the proliferation<br />

of SALW. Even though regional mechanisms for respond<strong>in</strong>g to conflict <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong><strong>security</strong> have suffered from weak capacity, limited resources <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> some cases an<br />

absence of political will, their <strong>role</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>fluence are slowly <strong>grow<strong>in</strong>g</strong>.<br />

As these multilateral organisations take on greater <strong>role</strong>s, Ch<strong>in</strong>a is <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly engag<strong>in</strong>g<br />

with the AU <strong>and</strong>, to a lesser degree, sub-regional organisations. Ch<strong>in</strong>a has played<br />

a constructive <strong>role</strong> <strong>in</strong> encourag<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>in</strong>ternational community to support <strong>African</strong><br />

regional <strong>and</strong> sub-regional actors <strong>in</strong> tackl<strong>in</strong>g <strong>security</strong> threats. Ch<strong>in</strong>a has also made<br />

pledges to assist regional <strong>security</strong> bodies. F<strong>in</strong>ancially, this support has largely been<br />

symbolic, for example Ch<strong>in</strong>a has provided the AU with $1.8 million for its <strong>peace</strong>keep<strong>in</strong>g<br />

mission <strong>in</strong> Sudan <strong>and</strong> given smaller amounts of money to the AU mission <strong>in</strong><br />

Somalia <strong>and</strong> West Africa’s sub-regional <strong>peace</strong> fund. 11 Though Ch<strong>in</strong>a may yet be<br />

reluctant to provide f<strong>in</strong>ancial assistance on the scale of other donors, <strong>in</strong>stitutionalis<strong>in</strong>g<br />

dialogue on <strong>security</strong> matters with the AU PSC <strong>and</strong> the relevant bodies of sub-regional<br />

organisations will allow Ch<strong>in</strong>a to identify other ways <strong>in</strong> which it can provide support.<br />

The provision of <strong>peace</strong>keep<strong>in</strong>g tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g to the ASF could be one such area.<br />

As regional bodies cont<strong>in</strong>ue to play a larger <strong>role</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>African</strong> political relations, Ch<strong>in</strong>a<br />

will follow suit. Yet for their part, the AU <strong>and</strong> its member states do not have any<br />

collective strategy to guide their own deal<strong>in</strong>gs with Ch<strong>in</strong>a. For Ch<strong>in</strong>a to provide<br />

greater levels of support to their <strong>peace</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>security</strong> efforts, <strong>African</strong> leaders will have<br />

to work more closely together <strong>and</strong> make a collective dem<strong>and</strong> for it.<br />

10 Amnesty International (2005), Democratic Republic of the Congo: Arm<strong>in</strong>g the East, London: Amnesty International.<br />

11 Van Hoeymissen, Sara (2010) ‘Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s Support to Africa’s Regional Security Architecture: Help<strong>in</strong>g Africa to Settle<br />

Conflicts <strong>and</strong> Keep the Peace’ <strong>in</strong> New Avenues for S<strong>in</strong>o-<strong>African</strong> Partnership & Co-operation – Ch<strong>in</strong>a & <strong>African</strong> Regional<br />

Organisations, The Ch<strong>in</strong>a Monitor, issue 49, March 2010, p 13.

vi<br />

c h i n a’ s g r o w i n g r o l e <strong>in</strong> a f r i c a n p e a c e a n d s e c u r i t y<br />

Co-operat<strong>in</strong>g with<br />

others<br />

Currently, most of Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s diplomatic engagement on <strong>African</strong> <strong>peace</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>security</strong> takes<br />

place at the UN Security Council (UNSC). S<strong>in</strong>ce rega<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s seat at the UN <strong>in</strong><br />

1971, Beij<strong>in</strong>g has become slowly but progressively more engaged at the UNSC, where<br />

nearly 60 percent of discussions focus on <strong>African</strong> <strong>security</strong> issues. Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s FOCAC<br />

commitments state that it will use its position on the UNSC to br<strong>in</strong>g <strong>African</strong> conflicts<br />

to the attention of the <strong>in</strong>ternational community. In this regard Ch<strong>in</strong>a has played a<br />

generally positive <strong>role</strong>, for example <strong>in</strong> push<strong>in</strong>g for action on Somalia. However, Ch<strong>in</strong>a<br />

ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>s that military <strong>in</strong>tervention <strong>in</strong> a state’s <strong>in</strong>ternal affairs is only legitimate if it<br />

has both UNSC authorisation <strong>and</strong> the consent of the host state. More broadly, Ch<strong>in</strong>a<br />

has argued that many <strong>in</strong>ternal crises fall outside of the UNSC’s m<strong>and</strong>ate. Officials have<br />

also made clear their scepticism regard<strong>in</strong>g the effectiveness of sanctions <strong>and</strong> other<br />

tools of coercion.<br />

Critics have argued that Ch<strong>in</strong>a has used the UNSC to protect partner regimes <strong>and</strong> its<br />

economic <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>in</strong> Africa. For example between 2004 <strong>and</strong> 2007 Ch<strong>in</strong>a consistently<br />

absta<strong>in</strong>ed from or weakened resolutions on the Darfur issue, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g those related<br />

to sanctions <strong>and</strong> the deployment of UN <strong>peace</strong>keepers. However, <strong>in</strong> 2007 Ch<strong>in</strong>a voted<br />

for the deployment of a jo<strong>in</strong>t UN-AU force <strong>in</strong> Darfur after Khartoum gave its consent –<br />

<strong>and</strong> this consent was to a large degree the result of Ch<strong>in</strong>ese pressure. While this<br />

develop ment perhaps signified that Beij<strong>in</strong>g was beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g to accept a more active <strong>role</strong><br />

for UN <strong>in</strong>tervention, it also shows that Ch<strong>in</strong>a has kept to its pr<strong>in</strong>cipled stance throughout.<br />

Some argue that this stance obstructs urgently needed <strong>in</strong>ternational action.<br />

Overall however, that Beij<strong>in</strong>g is will<strong>in</strong>g to demonstrate a commitment to multilateral<br />

responses to <strong>African</strong> <strong>security</strong> challenges is positive – even if some doubts rema<strong>in</strong> about<br />

the extent of this commitment.<br />

Through various FOCAC agreements Ch<strong>in</strong>a has pledged to represent <strong>African</strong> views at<br />

the UNSC, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> 2007 Ch<strong>in</strong>ese <strong>and</strong> <strong>African</strong> delegates at the UN set up a consultation<br />

mechanism. When Ch<strong>in</strong>a vetoed a UNSC resolution for sanctions on Zimbabwe <strong>in</strong><br />

2008, it claimed that the sanctions were not only <strong>in</strong>effective <strong>and</strong> poorly timed, but that<br />

Ch<strong>in</strong>a was represent<strong>in</strong>g the views of <strong>African</strong> states. However, some critical observers<br />

feel that Ch<strong>in</strong>a hides beh<strong>in</strong>d its stated policy of promot<strong>in</strong>g <strong>African</strong> positions as a<br />

means of legitimis<strong>in</strong>g its resistance to <strong>in</strong>ternational action. On the other h<strong>and</strong>, there<br />

is some evidence to suggest that Ch<strong>in</strong>a has voted for resolutions it would otherwise<br />

have opposed, on the basis of <strong>African</strong> pressure. How Ch<strong>in</strong>a balances <strong>and</strong> adapts its<br />

diplomatic <strong>role</strong> at the UNSC <strong>in</strong> relation to various dem<strong>and</strong>s placed on it from different<br />

stakeholders with<strong>in</strong> Africa rema<strong>in</strong>s to be seen.<br />

It is also unclear to what extent Beij<strong>in</strong>g is will<strong>in</strong>g to participate <strong>in</strong> other <strong>in</strong>ternational<br />

<strong>in</strong>itiatives. Ch<strong>in</strong>a has endorsed the pr<strong>in</strong>ciple of the Responsibility to Protect (R2P),<br />

although its <strong>in</strong>terpretation of its implementation rema<strong>in</strong>s qualified <strong>and</strong> cautious.<br />

Ch<strong>in</strong>a also supported the pr<strong>in</strong>ciples beh<strong>in</strong>d the International Crim<strong>in</strong>al Court (ICC),<br />

although it refused to endorse the Rome Statute that activated it. Beij<strong>in</strong>g has s<strong>in</strong>ce<br />

rema<strong>in</strong>ed vocally critical of the tim<strong>in</strong>g of the ICC’s <strong>in</strong>dictments of Sudan’s President<br />

Omar al-Bashir <strong>and</strong> while it has agreed that <strong>in</strong>dividuals must be bought to justice over<br />

violations of human rights <strong>and</strong> humanitarian law <strong>in</strong> Darfur, it has argued that no one<br />

has the right to challenge the immunity of a head of state.<br />

Another important aspect of Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s multilateral engagement on <strong>African</strong> <strong>peace</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>security</strong> has been its participation <strong>in</strong> anti-piracy efforts <strong>in</strong> the Gulf of Aden. While<br />

this deployment is <strong>in</strong> part motivated by geo-politics <strong>and</strong> the protection of national<br />

<strong>in</strong>terests, Ch<strong>in</strong>ese scholars have argued that it shows that Ch<strong>in</strong>a is will<strong>in</strong>g to share<br />

the burden of uphold<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>ternational <strong>peace</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>security</strong> as a responsible big power.<br />

This recognition is positive <strong>in</strong> view of Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s specific responsibilities vis-à-vis Africa’s<br />

challenges. In fact, Ch<strong>in</strong>ese officials have consistently argued that the <strong>in</strong>ternational<br />

community must do more to tackle the root of the problem: Somalia’s perpetual crisis.<br />

Furthermore, Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s participation <strong>in</strong> the anti-piracy mission has demonstrated that it<br />

is will<strong>in</strong>g to work <strong>in</strong> closer co-operation with other external actors.

s a f e r w o r l d vii<br />

This example may be an exception. In general, Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s <strong>in</strong>ternational co-operation with<br />

other external actors <strong>in</strong> Africa is extremely limited. Both the United States <strong>and</strong> the<br />

European Union have made efforts to co-operate more closely with Ch<strong>in</strong>a, with disappo<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g<br />

results. A host of factors underm<strong>in</strong>e such co-operation, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g a degree<br />

of scepticism <strong>in</strong> parts of Africa as to the underly<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>tentions of Western powers<br />

<strong>and</strong> the actual benefits of trilateral co-operation. Instead of seek<strong>in</strong>g co-operation on<br />

a broad range of generalised issues, Western states <strong>and</strong> Ch<strong>in</strong>a should look for specific<br />

areas for practical co-operation. However, it is <strong>African</strong> leaders who hold the key to<br />

successful co-operation <strong>and</strong> if they are serious about maximis<strong>in</strong>g the effectiveness of<br />

outside support they should actively promote it. In the long term, encourag<strong>in</strong>g<br />

co-operation between traditional <strong>and</strong> emerg<strong>in</strong>g powers may prove to be pivotal <strong>in</strong><br />

tackl<strong>in</strong>g <strong>grow<strong>in</strong>g</strong> suspicion between external actors ‘compet<strong>in</strong>g’ <strong>in</strong> Africa, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong><br />

prevent<strong>in</strong>g geopolitical competition from be<strong>in</strong>g violently played out <strong>in</strong> Africa as it has<br />

<strong>in</strong> the past.<br />

Keep<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> build<strong>in</strong>g<br />

the <strong>peace</strong><br />

UN <strong>peace</strong>keep<strong>in</strong>g missions <strong>in</strong> Africa play a significant <strong>role</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternational efforts to<br />

help resolve some of the cont<strong>in</strong>ent’s most persistent <strong>peace</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>security</strong> challenges.<br />

The 2009 FOCAC agreement states that the Ch<strong>in</strong>ese government will “cont<strong>in</strong>ue to<br />

support <strong>and</strong> participate <strong>in</strong> [these] <strong>peace</strong>keep<strong>in</strong>g missions.” 12 In parallel with its <strong>grow<strong>in</strong>g</strong><br />

engagement at the UNSC, Ch<strong>in</strong>a has <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly supported the deployment of<br />

UN <strong>peace</strong>keep<strong>in</strong>g operations. This marks a dramatic change from the 1970s when<br />

it refused to even vote on resolutions related to <strong>peace</strong>keep<strong>in</strong>g. From 1999 onwards,<br />

Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s stance on the use of force has become more flexible <strong>and</strong> less conservative, with<br />

some Ch<strong>in</strong>ese officials argu<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>peace</strong>keepers need to <strong>in</strong>tervene “earlier, faster <strong>and</strong><br />

more forcefully”. 13 Despite this shift, Ch<strong>in</strong>a cont<strong>in</strong>ues to require host state consent to<br />

<strong>peace</strong>keep<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>terventions. Given that some regimes lack legitimacy <strong>and</strong> may have<br />

only tenuous claims to represent the wishes of all parties to a conflict, this position will<br />

cont<strong>in</strong>ue to cause tensions with other members of the <strong>in</strong>ternational community. Nonetheless,<br />

that Ch<strong>in</strong>a has become an engaged party <strong>in</strong> UNSC deliberations on <strong>peace</strong>keep<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>and</strong> become more flexible over their m<strong>and</strong>ate is a very positive development.<br />

Ch<strong>in</strong>a has also begun to participate more actively <strong>in</strong> <strong>peace</strong>keep<strong>in</strong>g operations on the<br />

ground. S<strong>in</strong>ce 2000, when it deployed less than 100 <strong>peace</strong>keepers, Ch<strong>in</strong>a has <strong>in</strong>creased<br />

contributions of personnel 20-fold. 14 Of the Permanent Five members (P5) of the<br />

UNSC, Ch<strong>in</strong>a is the largest contributor of troops. The majority of Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s <strong>peace</strong>keepers<br />

are stationed <strong>in</strong> Africa. Ch<strong>in</strong>a has not yet contributed any combat troops to UN<br />

missions. Its <strong>peace</strong>keepers <strong>in</strong>stead hold positions as military observers, civilian police<br />

<strong>and</strong> units that provide <strong>in</strong>frastructure, medical, logistical <strong>and</strong> transport support.<br />

Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s <strong>grow<strong>in</strong>g</strong> personnel contributions to <strong>peace</strong>keep<strong>in</strong>g may be greatly beneficial to<br />

<strong>African</strong> <strong>peace</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>security</strong>. The UN’s dem<strong>and</strong> for <strong>peace</strong>keepers far outstrips supply:<br />

larger contributions from Ch<strong>in</strong>a help address this problem. Operationally, the professionalism<br />

of Ch<strong>in</strong>ese <strong>peace</strong>keepers has been praised. There are significant opportunities<br />

for Ch<strong>in</strong>a to widen the <strong>role</strong>s that its <strong>peace</strong>keepers play to <strong>in</strong>clude combat troops<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>volvement <strong>in</strong> more complex operations, for example actively carry<strong>in</strong>g out the<br />

disarmament of combatants. Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s participation <strong>in</strong> <strong>peace</strong>keep<strong>in</strong>g is likely to push<br />

it towards becom<strong>in</strong>g a more engaged actor on <strong>African</strong> <strong>peace</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>security</strong> challenges.<br />

This will also expose some of the latent contradictions of its current engagements, for<br />

example deploy<strong>in</strong>g its <strong>peace</strong>keepers to a country where the government cont<strong>in</strong>ues to<br />

fuel conflicts with arms that may be supplied by Ch<strong>in</strong>a.<br />

12 FOCAC (2009) Sharm el-Sheikh FOCAC Action Plan (2010–2012), 2.6.1.<br />

13 Zhang, Yishan, Ch<strong>in</strong>ese Ambassador to the UN, cited <strong>in</strong> Gill, Bates & Huang, Ch<strong>in</strong>-Hao (2009) Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s Exp<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g Role <strong>in</strong><br />

Peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g: Prospects <strong>and</strong> Policy Implications, SIPRI Policy Paper no. 25, p 11.<br />

14 Gill & Huang (2009), p 1.

viii<br />

c h i n a’ s g r o w i n g r o l e <strong>in</strong> a f r i c a n p e a c e a n d s e c u r i t y<br />

Ch<strong>in</strong>ese scholars suggest that their country is prepar<strong>in</strong>g to become more <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong><br />

post-conflict <strong>peace</strong>build<strong>in</strong>g, i.e. the use of a spectrum of <strong>security</strong>, civilian, adm<strong>in</strong>istrative,<br />

political, humanitarian <strong>and</strong> economic tools <strong>in</strong> order to support the establishment<br />

of longer term <strong>peace</strong>. Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s <strong>grow<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> this area is notable as <strong>in</strong> the past<br />

Beij<strong>in</strong>g was reluctant to get so <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> what it saw as domestic affairs. Given that<br />

half of all civil wars are actually post-conflict relapses, 15 extra support from Ch<strong>in</strong>a for<br />

<strong>peace</strong>build<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>itiatives will potentially be very valuable. While Ch<strong>in</strong>a shares with<br />

the West a belief <strong>in</strong> the benefits of strong state-build<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> economic development for<br />

post-conflict states, officials rema<strong>in</strong> deeply sceptical towards <strong>peace</strong>build<strong>in</strong>g agendas<br />

that <strong>in</strong>clude democratisation. Clearly, as <strong>in</strong> other areas, differences <strong>in</strong> approach<br />

may become obstacles to co-operation. There is a need for more discussion on what<br />

<strong>peace</strong>build<strong>in</strong>g should constitute <strong>in</strong> order to f<strong>in</strong>d areas where <strong>in</strong>ternational actors can<br />

co-operate more closely or, at the very least, identify areas where Western states <strong>and</strong><br />

Ch<strong>in</strong>a may be able to make complementary contributions.<br />

Conflict, <strong>security</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

development<br />

Ch<strong>in</strong>ese scholars <strong>and</strong> officials subscribe to the view that underdevelopment is a root<br />

cause of conflict. They argue that through its trade, <strong>in</strong>vestment <strong>and</strong> development<br />

assistance, Ch<strong>in</strong>a contributes to <strong>African</strong> economic growth <strong>and</strong> thus plays a positive<br />

<strong>role</strong> <strong>in</strong> promot<strong>in</strong>g <strong>African</strong> <strong>peace</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>security</strong>. That Ch<strong>in</strong>ese scholars <strong>and</strong> policy<br />

makers recognise the relationship between development <strong>and</strong> conflict <strong>and</strong> believe that<br />

Ch<strong>in</strong>a can play a beneficial <strong>role</strong> <strong>in</strong> seek<strong>in</strong>g to address these issues is commendable.<br />

However there are some critical questions over whether this engagement is as effective<br />

as believed.<br />

Firstly, while economic development is important, it cannot be delivered <strong>in</strong> a context<br />

of <strong>in</strong><strong>security</strong>. For example <strong>in</strong> post-conflict states Ch<strong>in</strong>a can potentially play a very constructive<br />

<strong>role</strong> <strong>in</strong> provid<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>vestment, much-needed <strong>in</strong>frastructure <strong>and</strong> employment.<br />

However, there is a risk that economic assistance will come to be prioritised at the cost<br />

of <strong>security</strong> factors such as tackl<strong>in</strong>g arms proliferation or demobilis<strong>in</strong>g militias. Peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g<br />

must be delivered <strong>in</strong> a holistic manner: economic assistance is not a substitute<br />

for work<strong>in</strong>g directly to tackle conflict. There is a wider danger that the supposed<br />

benefits of economic assistance will be used to justify <strong>in</strong>action on other equally<br />

important fronts such as address<strong>in</strong>g deeply entrenched political grievances.<br />

Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s non-<strong>in</strong>terference pr<strong>in</strong>ciples mean that it is uncomfortable becom<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>volved<br />

<strong>in</strong> what it underst<strong>and</strong>s to be <strong>in</strong>ternal political affairs. However, through its economic<br />

engagements Ch<strong>in</strong>a <strong>in</strong>evitably does. This is illustrated most strik<strong>in</strong>gly by its <strong>in</strong>volvement<br />

<strong>in</strong> conflicts surround<strong>in</strong>g natural resources. Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s unparalleled <strong>and</strong> rapid<br />

economic growth over the last three decades has created a dem<strong>and</strong> for energy <strong>and</strong><br />

m<strong>in</strong>eral resources from outside Ch<strong>in</strong>a. In 2006 alone, its <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> oil dem<strong>and</strong><br />

represented nearly half of the world’s total <strong>in</strong>crease. 16 Today Ch<strong>in</strong>a is the world’s largest<br />

consumer of oil.<br />

Africa has assumed a critical <strong>role</strong> <strong>in</strong> meet<strong>in</strong>g Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s dem<strong>and</strong> for resources. However,<br />

this quest for resource <strong>security</strong> has drawn Ch<strong>in</strong>a <strong>in</strong>to <strong>in</strong>ternal conflicts surround<strong>in</strong>g<br />

natural resources. Ch<strong>in</strong>ese oil <strong>in</strong>stallations <strong>and</strong> workers have been directly targeted by<br />

armed groups <strong>in</strong> several countries. In cases where the ownership of natural resources<br />

is highly contested – as <strong>in</strong> Nigeria – Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s <strong>role</strong> <strong>in</strong> their extraction has made it a party<br />

to the conflict <strong>in</strong> the eyes of those who feel cheated of the profits from resources.<br />

Revenue from resources sold to Ch<strong>in</strong>a has on occasions been used to buy weapons<br />

that fuel conflict, for example <strong>in</strong> Sudan. More broadly, there have been <strong>in</strong>stances<br />

where this revenue has allowed patronage-based regimes to ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> their grip on<br />

power <strong>and</strong> enrich themselves. In the long term, this impact on governance may lead<br />

15 Collier, Paul (2007) The Bottom Billion: why the poorest countries are fail<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> what can be done about it, Oxford: Oxford<br />

University Press.<br />

16 International Crisis Group (2009) Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s Grow<strong>in</strong>g Role <strong>in</strong> UN Peacekeep<strong>in</strong>g, Asia Report no.166, p 3.

s a f e r w o r l d ix<br />

to further cycles of <strong>in</strong>stability <strong>and</strong> violence. Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s dem<strong>and</strong> for natural resources has<br />

meant that it has not only become an <strong>in</strong>volved actor <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternal affairs, but that <strong>in</strong> some<br />

cases it has re<strong>in</strong>forced <strong>and</strong> fuelled pre-exist<strong>in</strong>g conflict dynamics. This be<strong>in</strong>g the case,<br />

it is of fundamental importance that Beij<strong>in</strong>g develops better policies <strong>and</strong> regulations<br />

govern<strong>in</strong>g the trade <strong>in</strong> resources from countries or regions fac<strong>in</strong>g ongo<strong>in</strong>g conflicts.<br />

Such dynamics are by no means unique to Ch<strong>in</strong>a. Plenty of Western companies<br />

operate <strong>in</strong> the resource sectors of the same unstable countries as Ch<strong>in</strong>a <strong>and</strong> have been<br />

dragged <strong>in</strong>to local dynamics, fuelled conflicts <strong>and</strong> enriched dubious regimes. That<br />

Ch<strong>in</strong>a buys <strong>African</strong> resources is by no means <strong>in</strong>herently negative <strong>and</strong> it is <strong>African</strong><br />

governments that hold primary responsibility for their management: resources do<br />

not cause conflict on their own. Moreover, many of the resources Ch<strong>in</strong>a imports from<br />

Africa are manufactured <strong>in</strong>to consumer goods that are sold on <strong>in</strong>ternational markets.<br />

In a globalised world the attribution of blame for Africa’s resource conflicts is multilayered<br />

<strong>and</strong> complex. As such, the solutions must be global. Initiatives such as the<br />

Kimberly Process to stop trade <strong>in</strong> conflict diamonds <strong>and</strong> the Extractive Industries<br />

Transparency Initiative (EITI) suggest that progress <strong>in</strong> this direction is start<strong>in</strong>g to be<br />

made. Ch<strong>in</strong>ese officials <strong>and</strong> scholars frequently contend that globalisation benefits rich<br />

Western countries at the expense of the poor. Tak<strong>in</strong>g the lead <strong>in</strong> driv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>ter national<br />

co-operation to more effectively ensure that the global trade <strong>in</strong> Africa’s natural<br />

resources best serves Africa’s people would be a positive example of south-south<br />

co-operation.<br />

Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s <strong>role</strong> <strong>in</strong> Africa’s water management illustrates how even seem<strong>in</strong>gly harmless<br />

development assistance can fuel conflict. As part of Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s wider participation <strong>in</strong><br />

Africa’s <strong>in</strong>frastructure development, Ch<strong>in</strong>ese f<strong>in</strong>ance <strong>and</strong> companies had been<br />

<strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> the construction of 25 dams <strong>in</strong> Africa by 2008. 17 Some of these projects<br />

have been highly controversial because they may fuel localised conflict dynamics <strong>and</strong><br />

competition over scarce water supplies. Peaceful aims do not always guarantee <strong>peace</strong>ful<br />

outcomes <strong>and</strong> even well mean<strong>in</strong>g development programmes can fuel conflict.<br />

As the cases of post-conflict economic assistance, natural resource extraction <strong>and</strong><br />

water all highlight, the assumption that Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s economic relations <strong>and</strong> assistance to<br />

Africa are always <strong>in</strong>herently pro-<strong>peace</strong> is a simplified <strong>and</strong> mistaken one. Without<br />

ab<strong>and</strong>on<strong>in</strong>g what are admirable <strong>in</strong>tentions, Ch<strong>in</strong>ese scholars <strong>and</strong> policy makers<br />

should beg<strong>in</strong> to take a more conflict-sensitive approach to development if their<br />

country is to become the partner for <strong>African</strong> development that they aspire it to be.<br />

Towards a more<br />

co-operative approach<br />

to <strong>African</strong> <strong>peace</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>security</strong><br />

Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s <strong>role</strong> <strong>in</strong> Africa <strong>and</strong> the impact of this <strong>role</strong> on Africa’s various conflict <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong><strong>security</strong> challenges has been neither wholly positive nor wholly negative. Given its<br />

deepen<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>terests on the cont<strong>in</strong>ent, its commitment to <strong>African</strong> development <strong>and</strong><br />

its wish to be seen as a responsible power, there is scope for Ch<strong>in</strong>a to become more<br />

supportive of <strong>African</strong> <strong>peace</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>security</strong>. In some cases, most press<strong>in</strong>gly with regards<br />

to arms transfers, policies could <strong>and</strong> should be improved. In other cases, such as its<br />

economic engagement, policies could be made more sensitive to conflict risks. In other<br />

areas, such as <strong>peace</strong>keep<strong>in</strong>g, Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s successful contributions should be built upon.<br />

Several themes are highlighted throughout this report. Firstly, although economic<br />

co-operation will rema<strong>in</strong> a priority <strong>in</strong> its relations with <strong>African</strong> countries, Ch<strong>in</strong>a is<br />

<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly engag<strong>in</strong>g on conflict <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong><strong>security</strong> issues across the cont<strong>in</strong>ent. This<br />

engagement has gradually become more proactive <strong>and</strong>, to a degree, more flexible.<br />

Secondly, <strong>and</strong> despite these tentative changes, there clearly rema<strong>in</strong> entrenched differences<br />

with traditional Western states over how assistance to Africa is best delivered.<br />

Greater levels of dialogue between Western <strong>and</strong> Ch<strong>in</strong>ese policy makers will help<br />

17 International Rivers (2008) The New Great Walls: A Guide to Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s Overseas Dam Industry, Berkeley: International Rivers<br />

p 17.

x<br />

c h i n a’ s g r o w i n g r o l e <strong>in</strong> a f r i c a n p e a c e a n d s e c u r i t y<br />

navigate differences <strong>and</strong> promote greater co-operation to meet common goals <strong>and</strong><br />

overcome shared fail<strong>in</strong>gs. Thirdly, solutions to Africa’s <strong>peace</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>security</strong> challenges<br />

are ultimately the responsibility of the cont<strong>in</strong>ent’s own governments <strong>and</strong> civil society.<br />

To this end they should dem<strong>and</strong> that Ch<strong>in</strong>a contributes more to support<strong>in</strong>g <strong>peace</strong>,<br />

that it is sensitive to <strong>African</strong> <strong>security</strong> <strong>and</strong> that it is held to account when it is not.<br />

Furthermore they must ensure that all external actors work together rather than<br />

aga<strong>in</strong>st one another. At such a critical juncture <strong>in</strong> Africa’s history, the management of<br />

these relations will greatly determ<strong>in</strong>e future prospects for the cont<strong>in</strong>ent’s <strong>peace</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

development.

<strong>Saferworld</strong> works to prevent <strong>and</strong> reduce violent conflict <strong>and</strong> promote<br />

co-operative approaches to <strong>security</strong>. We work with governments,<br />

<strong>in</strong>ternational organisations <strong>and</strong> civil society to encourage <strong>and</strong> support<br />

effective policies <strong>and</strong> practices through advocacy, research <strong>and</strong> policy<br />

development <strong>and</strong> through support<strong>in</strong>g the actions of others.<br />

COVER PHOTO: Zwedru, Liberia – A medal parade honour<strong>in</strong>g the Ch<strong>in</strong>ese<br />

<strong>peace</strong>keep<strong>in</strong>g cont<strong>in</strong>gent of the United Nations Mission <strong>in</strong> Liberia (UNMIL).<br />

First deployed <strong>in</strong> March 2004, Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s largest cont<strong>in</strong>gent of <strong>peace</strong>keepers<br />

serves <strong>in</strong> Liberia. © 2008 CHRISTOPHER HERWIG<br />

UK OFFICE<br />

The Grayston Centre<br />

28 Charles Square<br />

London N1 6HT<br />

UK<br />

Phone: +44 (0)20 7324 4646<br />

Email: general@saferworld.org.uk<br />

Web: www.saferworld.org.uk<br />

KENYA OFFICE<br />

PO Box 21484-00505<br />

Adams Arcade<br />

Nairobi<br />

Kenya<br />

+254 (0)20 271 3603<br />

+254 (0)20 273 3250/<br />

6480/6484<br />

SUDAN OFFICE<br />

Hamza Inn<br />

Juba Town<br />

Juba<br />

Southern Sudan<br />

+249 (0)924 430042<br />

+249 (0)955 083361<br />

UGANDA OFFICE<br />

PO Box 8415<br />

Kampala<br />

Ug<strong>and</strong>a<br />

+256 (0)414 231130/<br />

+256 (0)414 231150<br />

Registered charity no. 1043843<br />

A company limited by guarantee<br />

no. 3015948<br />

ISBN 978–1–904833–57–4