Download - Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study - Harvard University

Download - Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study - Harvard University

Download - Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study - Harvard University

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

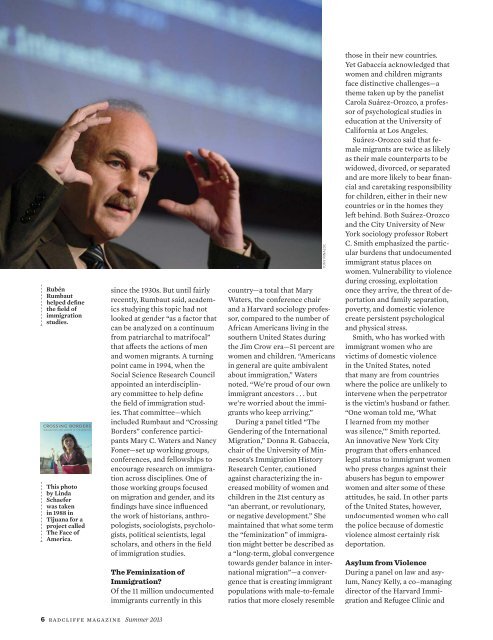

Rubén<br />

Rumbaut<br />

helped define<br />

the field of<br />

immigration<br />

studies.<br />

crossing borders<br />

immigration and gender in the americas<br />

This photo<br />

by Linda<br />

Schaefer<br />

was taken<br />

in 1988 in<br />

Tijuana <strong>for</strong> a<br />

project called<br />

The Face of<br />

America.<br />

since the 1930s. But until fairly<br />

recently, Rumbaut said, academics<br />

studying this topic had not<br />

looked at gender “as a factor that<br />

can be analyzed on a continuum<br />

from patriarchal to matrifocal”<br />

that affects the actions of men<br />

and women migrants. A turning<br />

point came in 1994, when the<br />

Social Science Research Council<br />

appointed an interdisciplinary<br />

committee to help define<br />

the field of immigration stud-<br />

ies. That committee—which<br />

included Rumbaut and “Crossing<br />

Borders” conference participants<br />

Mary C. Waters and Nancy<br />

Foner—set up working groups,<br />

conferences, and fellowships to<br />

encourage research on immigration<br />

across disciplines. One of<br />

those working groups focused<br />

on migration and gender, and its<br />

findings have since infl<br />

uenced<br />

the work of historians, anthropologists,<br />

sociologists, psychologists,<br />

political scientists, legal<br />

scholars, and others in the field<br />

of immigration studies.<br />

The Feminization of<br />

Immigration<br />

Of the 11 million undocumented<br />

immigrants currently in this<br />

TONY RINALDO<br />

country—a total that Mary<br />

Waters, the conference chair<br />

and a <strong>Harvard</strong> sociology professor,<br />

compared to the number of<br />

African Americans living in the<br />

southern United States during<br />

the Jim Crow era—51 percent are<br />

women and children. “Americans<br />

in general are quite ambivalent<br />

about immigration,” Waters<br />

noted. “We’re proud of our own<br />

immigrant ancestors . . . but<br />

we’re worried about the immigrants<br />

who keep arriving.”<br />

During a panel titled “The<br />

Gendering of the International<br />

Migration,” Donna R. Gabaccia,<br />

chair of the <strong>University</strong> of Minnesota’s<br />

Immigration History<br />

Research Center, cautioned<br />

against characterizing the increased<br />

mobility of women and<br />

children in the 21st century as<br />

“an aberrant, or revolutionary,<br />

or negative development.” She<br />

maintained that what some term<br />

the “feminization” of immigration<br />

might better be described as<br />

a “long-term, global convergence<br />

towards gender balance in international<br />

migration”—a convergence<br />

that is creating immigrant<br />

populations with male-to-female<br />

ratios that more closely resemble<br />

those in their new countries.<br />

Yet Gabaccia acknowledged that<br />

women and children migrants<br />

face distinctive challenges—a<br />

theme taken up by the panelist<br />

Carola Suárez-Orozco, a professor<br />

of psychological studies in<br />

education at the <strong>University</strong> of<br />

Cali<strong>for</strong>nia at Los Angeles.<br />

Suárez-Orozco said that female<br />

migrants are twice as likely<br />

as their male counterparts to be<br />

widowed, divorced, or separated<br />

and are more likely to bear finan-<br />

cial and caretaking responsibility<br />

<strong>for</strong> children, either in their new<br />

countries or in the homes they<br />

left behind. Both Suárez-Orozco<br />

and the City <strong>University</strong> of New<br />

York sociology professor Robert<br />

C. Smith emphasized the particular<br />

burdens that undocumented<br />

immigrant status places on<br />

women. Vulnerability to violence<br />

during crossing, exploitation<br />

once they arrive, the threat of deportation<br />

and family separation,<br />

poverty, and domestic violence<br />

create persistent psychological<br />

and physical stress.<br />

Smith, who has worked with<br />

immigrant women who are<br />

victims of domestic violence<br />

in the United States, noted<br />

that many are from countries<br />

where the police are unlikely to<br />

intervene when the perpetrator<br />

is the victim’s husband or father.<br />

“One woman told me, ‘What<br />

I learned from my mother<br />

was silence,’” Smith reported.<br />

An innovative New York City<br />

program that offers enhanced<br />

legal status to immigrant women<br />

who press charges against their<br />

abusers has begun to empower<br />

women and alter some of these<br />

attitudes, he said. In other parts<br />

of the United States, however,<br />

undocumented women who call<br />

the police because of domestic<br />

violence almost certainly risk<br />

deportation.<br />

Asylum from Violence<br />

During a panel on law and asylum,<br />

Nancy Kelly, a co–managing<br />

director of the <strong>Harvard</strong> Immigration<br />

and Refugee Clinic and<br />

6 radcliffe magazine Summer 2013