The Differentiation of Frontotemporal Dementia ... - McLean Hospital

The Differentiation of Frontotemporal Dementia ... - McLean Hospital

The Differentiation of Frontotemporal Dementia ... - McLean Hospital

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

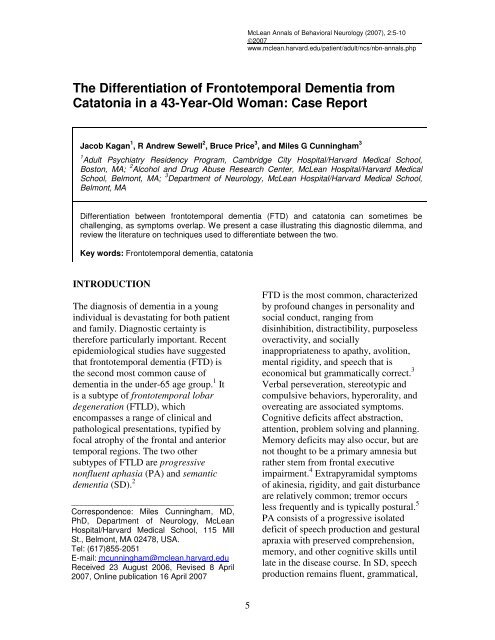

<strong>McLean</strong> Annals <strong>of</strong> Behavioral Neurology (2007), 2:5-10<br />

©2007<br />

www.mclean.harvard.edu/patient/adult/ncs/nbn-annals.php<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Differentiation</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Frontotemporal</strong> <strong>Dementia</strong> from<br />

Catatonia in a 43-Year-Old Woman: Case Report<br />

Jacob Kagan 1 , R Andrew Sewell 2 , Bruce Price 3 , and Miles G Cunningham 3<br />

1 Adult Psychiatry Residency Program, Cambridge City <strong>Hospital</strong>/Harvard Medical School,<br />

Boston, MA; 2 Alcohol and Drug Abuse Research Center, <strong>McLean</strong> <strong>Hospital</strong>/Harvard Medical<br />

School, Belmont, MA; 3 Department <strong>of</strong> Neurology, <strong>McLean</strong> <strong>Hospital</strong>/Harvard Medical School,<br />

Belmont, MA<br />

<strong>Differentiation</strong> between frontotemporal dementia (FTD) and catatonia can sometimes be<br />

challenging, as symptoms overlap. We present a case illustrating this diagnostic dilemma, and<br />

review the literature on techniques used to differentiate between the two.<br />

Key words: <strong>Frontotemporal</strong> dementia, catatonia<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

<strong>The</strong> diagnosis <strong>of</strong> dementia in a young<br />

individual is devastating for both patient<br />

and family. Diagnostic certainty is<br />

therefore particularly important. Recent<br />

epidemiological studies have suggested<br />

that frontotemporal dementia (FTD) is<br />

the second most common cause <strong>of</strong><br />

dementia in the under-65 age group. 1 It<br />

is a subtype <strong>of</strong> frontotemporal lobar<br />

degeneration (FTLD), which<br />

encompasses a range <strong>of</strong> clinical and<br />

pathological presentations, typified by<br />

focal atrophy <strong>of</strong> the frontal and anterior<br />

temporal regions. <strong>The</strong> two other<br />

subtypes <strong>of</strong> FTLD are progressive<br />

nonfluent aphasia (PA) and semantic<br />

dementia (SD). 2<br />

________________________________________<br />

Correspondence: Miles Cunningham, MD,<br />

PhD, Department <strong>of</strong> Neurology, <strong>McLean</strong><br />

<strong>Hospital</strong>/Harvard Medical School, 115 Mill<br />

St., Belmont, MA 02478, USA.<br />

Tel: (617)855-2051<br />

E-mail: mcunningham@mclean.harvard.edu<br />

Received 23 August 2006, Revised 8 April<br />

2007, Online publication 16 April 2007<br />

FTD is the most common, characterized<br />

by pr<strong>of</strong>ound changes in personality and<br />

social conduct, ranging from<br />

disinhibition, distractibility, purposeless<br />

overactivity, and socially<br />

inappropriateness to apathy, avolition,<br />

mental rigidity, and speech that is<br />

economical but grammatically correct. 3<br />

Verbal perseveration, stereotypic and<br />

compulsive behaviors, hyperorality, and<br />

overeating are associated symptoms.<br />

Cognitive deficits affect abstraction,<br />

attention, problem solving and planning.<br />

Memory deficits may also occur, but are<br />

not thought to be a primary amnesia but<br />

rather stem from frontal executive<br />

impairment. 4 Extrapyramidal symptoms<br />

<strong>of</strong> akinesia, rigidity, and gait disturbance<br />

are relatively common; tremor occurs<br />

less frequently and is typically postural. 5<br />

PA consists <strong>of</strong> a progressive isolated<br />

deficit <strong>of</strong> speech production and gestural<br />

apraxia with preserved comprehension,<br />

memory, and other cognitive skills until<br />

late in the disease course. In SD, speech<br />

production remains fluent, grammatical,<br />

5

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Differentiation</strong> <strong>of</strong> Catatonia from <strong>Frontotemporal</strong><br />

<strong>Dementia</strong> in a 43-Year-Old Woman<br />

J Kagan et al.<br />

and free <strong>of</strong> paraphrasias but<br />

comprehension deteriorates, face<br />

recognition disappears, and patients also<br />

exhibit difficulty in recognizing the<br />

significance <strong>of</strong> objects.<br />

Although catatonia is historically<br />

considered a symptom <strong>of</strong> schizophrenia,<br />

it actually occurs more frequently during<br />

the course <strong>of</strong> a mood disorder, 6 and the<br />

DSM-IV-TR reflects this newer thinking<br />

about catatonia by adding catatonia as a<br />

specifier in mood disorders and as a<br />

separate syndrome occurring secondary<br />

to a general medical disorder. 7 Catatonia<br />

shares a number <strong>of</strong> characteristics with<br />

FTD (see Table 1)—paucity <strong>of</strong> speech,<br />

stereotyped or repetitive behaviors,<br />

purposeless and excessive motor<br />

activity, and echolalia. <strong>Differentiation</strong><br />

between catatonia and FTD may<br />

therefore be challenging. <strong>The</strong> following<br />

case illustrates this clinical overlap and<br />

underscores the critical importance <strong>of</strong><br />

diagnostic certainty for accurate<br />

prognosis and delineation <strong>of</strong> patient and<br />

caregiver psychosocial burden.<br />

CASE REPORT<br />

A 43-year-old married white woman<br />

presented with what her family noted to<br />

be a two-year history <strong>of</strong> progressive<br />

behavioral changes, including flattened<br />

affect, social withdrawal, compulsions,<br />

increased appetite, decreased speech,<br />

depression, and complaints <strong>of</strong> memory<br />

loss. A year prior to admission, a<br />

psychiatric nurse practitioner had noted<br />

that the patient had complained <strong>of</strong><br />

depressed mood, had a significantly<br />

flattened affect, and spoke largely using<br />

“yes” and “no” answers. She had also<br />

become increasingly socially withdrawn,<br />

had recently been fired from her position<br />

as a kindergarten teachers’ aide, and had<br />

begun compulsively showering and<br />

using the dishwasher and clothes washer.<br />

She gained over 50 pounds, frequently<br />

binging on carbohydrate-rich foods. She<br />

had grown increasingly less able to care<br />

for herself and maintain safety within the<br />

house. A few months prior to admission,<br />

the patient accidentally lit a blanket on<br />

fire on the stove and in her confusion,<br />

did not know what to do with the<br />

burning blanket. Shortly thereafter, the<br />

patient’s 23-year-old son moved back<br />

home in order to help care for his mother<br />

while her husband was traveling.<br />

Because <strong>of</strong> her bizarre behavior and<br />

apparent depressed mood and<br />

neurovegetative symptoms, she was<br />

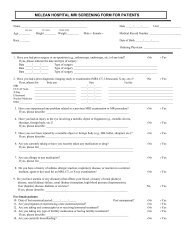

Criterion A. Any <strong>of</strong>: (two required in diagnosis <strong>of</strong> catatonic schizophrenia)<br />

Motoric immobility as evidenced by cataplexy or stupor<br />

Excessive motor activity (apparently purposeless)<br />

Mutism or extreme negativism (motiveless resistance to instructions or maintenance<br />

<strong>of</strong> rigid posture)<br />

Peculiarities <strong>of</strong> voluntary movement (inappropriate or bizarre postures, stereotyped<br />

movements, prominent mannerisms, or prominent grimacing)<br />

Echolalia or echopraxia<br />

Criterion B: Symptoms are the direct result <strong>of</strong> a general medical condition<br />

Criterion C: Symptoms are not better accounted for by another mental disorder<br />

Criterion D: Symptoms do not occur exclusively during the course <strong>of</strong> a delirium<br />

Table 1: DSM-IV-TR criteria for Catatonic Disorder due to a General Medical<br />

Condition 16.<br />

_________________________________<br />

<strong>McLean</strong> Annals <strong>of</strong> Behavioral Neurology<br />

6

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Differentiation</strong> <strong>of</strong> Catatonia from <strong>Frontotemporal</strong><br />

<strong>Dementia</strong> in a 43-Year-Old Woman<br />

J Kagan et al.<br />

diagnosed with depression with<br />

psychotic features, and given<br />

unsuccessful trials <strong>of</strong> citalopram,<br />

venlafaxine, bupropion, nortriptyline,<br />

methylphenidate, and risperidone. She<br />

then underwent 20 sessions <strong>of</strong> bilateral<br />

electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), also<br />

without response. One week following<br />

her course <strong>of</strong> ECT, the patient was<br />

hospitalized for suicidal ideation,<br />

stabilized, and discharged two weeks<br />

later, but soon after discharge again<br />

endorsed thoughts <strong>of</strong> cutting her wrists,<br />

so was brought into our acute psychiatric<br />

care center for evaluation.<br />

<strong>The</strong> patient was a high school graduate<br />

who had completed some college-level<br />

coursework before dropping out to begin<br />

working full time. She had worked as an<br />

aide in an elder care facility and in a<br />

kindergarten class. <strong>The</strong>re was no history<br />

<strong>of</strong> dementia in the family, although the<br />

patient’s mother had a history <strong>of</strong><br />

depression and the patient’s father had<br />

died at age 45 <strong>of</strong> lung cancer.<br />

On examination, she had a severely<br />

flattened affect, echolalia, poverty <strong>of</strong><br />

speech with almost exclusive use <strong>of</strong> the<br />

words “yes” and “no”, and mild<br />

psychomotor agitation. On cognitive<br />

testing she was inattentive and had<br />

impaired recall, abstraction, and a<br />

relative anomia, but preserved<br />

visuospatial functioning. Neurological<br />

exam showed a fine postural tremor in<br />

the patient’s left great toe and foot, but<br />

no rigidity, gait abnormalities, or<br />

primitive reflexes. Basic blood count,<br />

chemistries, liver function tests, and<br />

urinalysis were normal with the<br />

exception <strong>of</strong> a mild normocytic anemia.<br />

Serum vitamin B 12 , folate, erythrocyte<br />

sedimentation rate (ESR),<br />

ceruloplasmin, serum lyme titers, and<br />

autoimmune panel were negative. Rapid<br />

plasma reagin (RPR) was non-reactive.<br />

A lumbar puncture revealed a mildly<br />

elevated opening pressure (24 mm H 2 O),<br />

but normal glucose, protein, and cell<br />

counts, non-reactive CSF syphilis<br />

serology, and no cryptococcal antigens.<br />

An electroencephalogram (EEG)<br />

disclosed low-voltage beta activity,<br />

intermittent low-voltage 9 Hz alpha<br />

activity and low-voltage slowing with<br />

drowsiness, but no epileptiform activity.<br />

MRI revealed minimally increased extracerebral<br />

space, suggesting mild early<br />

involutional changes.<br />

Neuropsychological evaluation that had<br />

been performed four months prior to<br />

admission had demonstrated impaired<br />

attention and concentration, impaired<br />

verbal and narrative memory, and<br />

significant perseveration in her<br />

responses to the <strong>The</strong>matic Apperception<br />

Test and Rorschach Test.<br />

Visuoperceptual and organizational<br />

functions were also below average in<br />

unstructured situations (Rey figure<br />

memory), but normal when structure was<br />

applied (Hooper Test).<br />

On admission, the patient was taking<br />

methylphenidate, venlafaxine, and<br />

risperidone. Lorazepam was added and<br />

titrated to 8 mg a day in the first week <strong>of</strong><br />

admission, but the patient’s presentation<br />

varied little for the remainder <strong>of</strong><br />

hospitalization. She remained minimally<br />

communicative, perseverative, and<br />

echolalic, with flattened affect, persistent<br />

purposeless activity and compulsive<br />

grooming behaviors. Three weeks later,<br />

she was discharged with a presumptive<br />

diagnosis <strong>of</strong> FTD, with plans to followup<br />

in a partial hospitalization/day<br />

program. Venlafaxine was discontinued<br />

with plans to initiate treatment with a<br />

SSRI.<br />

_________________________________<br />

<strong>McLean</strong> Annals <strong>of</strong> Behavioral Neurology<br />

7

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Differentiation</strong> <strong>of</strong> Catatonia from <strong>Frontotemporal</strong><br />

<strong>Dementia</strong> in a 43-Year-Old Woman<br />

J Kagan et al.<br />

DISCUSSION<br />

While an age <strong>of</strong> onset younger than 45 is<br />

unusual in FTD, it can not be used as an<br />

exclusion criterion, as FTD has been<br />

documented in the fourth and even third<br />

decade <strong>of</strong> life. 1, 8 Similarly, while current<br />

hallucinations or delusions are not<br />

typical <strong>of</strong> FTD, they may also be absent<br />

in schizophrenia with predominantly<br />

negative symptoms or a catatonia from a<br />

mood disorder. 8 Delusions and<br />

hallucinations may likewise occur in a<br />

small percentage <strong>of</strong> FTD patients,<br />

although they occur less frequently than<br />

other behavioral symptoms. 9<br />

Multiple imaging modalities have been<br />

used to examine FTD and catatonia,<br />

although none have compared the two<br />

directly. MRI <strong>of</strong> patients with FTD<br />

typically reveals severe frontal, anterior<br />

temporal, and anterior parietal atrophy<br />

with a characteristic asymmetric pattern<br />

<strong>of</strong> atrophy. 10, 11 Specific patterns include<br />

disinhibition associated with<br />

predominant atrophy <strong>of</strong> the orbitomedial<br />

frontal and anterior temporal regions,<br />

apathy associated with extensive frontal<br />

lobe and dorsolateral frontal lobe<br />

atrophy, and semantic impairment<br />

associated with volume loss throughout<br />

the left anterior temporal lobe, right<br />

12, 13<br />

temporal pole and subcallosal gyrus.<br />

While there is some evidence to suggest<br />

prefrontal volume loss in schizophrenic<br />

patients, the evidence is inconclusive, 14<br />

and no studies have reported<br />

morphological abnormalities specific to<br />

catatonia. Single photon emission<br />

computed tomography (SPECT) imaging<br />

has revealed severe reductions in frontal<br />

rCBF in FTD patients, 10 but similar<br />

reductions in rCBF have been found in<br />

catatonic patients in the right lower and<br />

middle prefrontal regions and parietal<br />

cortical regions. 15 Positron emission<br />

tomography (PET) imaging <strong>of</strong> FTD has<br />

revealed glucose hypometabolism<br />

predominantly in the frontal and anterior<br />

temporal lobes and abnormalities in the<br />

cingulate gyri, uncus, insula, and<br />

subcortical structures including basal<br />

17, 18<br />

ganglia and medial thalamic regions.<br />

PET studies in catatonic patients have<br />

been more limited, however, one<br />

examination <strong>of</strong> three patients with<br />

speech-sluggish catatonia revealed<br />

bitemporal and bifrontal glucose<br />

hypometabolism and bi-thalamic<br />

hypermetabolism. 19 To date, multiple<br />

imaging modalities therefore show<br />

significant overlap in findings between<br />

catatonia and FTD—perhaps related to<br />

common frontal neurocircuitry—but<br />

there are no studies directly comparing<br />

the two groups.<br />

CONCLUSION<br />

We describe a patient with the early<br />

onset <strong>of</strong> a number <strong>of</strong> disabling,<br />

progressive symptoms including<br />

prominently flattened affect, paucity <strong>of</strong><br />

speech with maintained grammatical<br />

structure, verbal and physical<br />

perseveration, purposeless motor<br />

activity, and deficits in attention,<br />

concentration, abstraction, and memory.<br />

Laboratory investigations for infectious,<br />

metabolic and inflammatory processes<br />

were unrevealing and MRI suggested<br />

early frontal lobe atrophy. While the<br />

differential diagnosis <strong>of</strong> an early onset<br />

dementing process is large, this patient’s<br />

presentation was highly suggestive <strong>of</strong> a<br />

mood-disorder-associated catatonia or<br />

FTD. We are unaware <strong>of</strong> prior case<br />

reports describing this diagnostic<br />

challenge. <strong>The</strong> importance <strong>of</strong> correct<br />

diagnosis <strong>of</strong> FTD in a young, formerly<br />

_________________________________<br />

<strong>McLean</strong> Annals <strong>of</strong> Behavioral Neurology<br />

8

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Differentiation</strong> <strong>of</strong> Catatonia from <strong>Frontotemporal</strong><br />

<strong>Dementia</strong> in a 43-Year-Old Woman<br />

J Kagan et al.<br />

high-functioning individual can not be<br />

overestimated, given the rapid<br />

progression and limited life expectancy<br />

in this disorder. 20 Age <strong>of</strong> onset, clinical<br />

presentation, and neuroimaging are not<br />

helpful in differentiating catatonia from<br />

FTD, but our patient’s non-response to<br />

both ECT trials and lorazepam challenge<br />

proved diagnostic in this case, as<br />

catatonia has been shown to be<br />

remarkably responsive to both treatment<br />

modalities. 7, 21, 22 Future research directly<br />

comparing catatonia and FTD might<br />

further delineate the diagnostic utility <strong>of</strong><br />

MRI, PET, SPECT and fMRI, but until<br />

then, clinical judgment and judicious<br />

trials <strong>of</strong> lorazepam and ECT are the most<br />

appropriate tools available to clarify this<br />

difficult diagnostic challenge.<br />

REFERENCES<br />

1. Ratnavalli E, Brayne C, Dawson<br />

K, Hodges JR. <strong>The</strong> prevalence <strong>of</strong><br />

frontotemporal dementia.<br />

Neurology. Jun 11<br />

2002;58(11):1615-1621.<br />

2. Neary D, Snowden JS, Gustafson<br />

L, et al. <strong>Frontotemporal</strong> lobar<br />

degeneration: a consensus on<br />

clinical diagnostic criteria.<br />

Neurology. Dec<br />

1998;51(6):1546-1554.<br />

3. Johnson JK, Diehl J, Mendez<br />

MF, et al. <strong>Frontotemporal</strong> lobar<br />

degeneration: demographic<br />

characteristics <strong>of</strong> 353 patients.<br />

Arch Neurol. Jun<br />

2005;62(6):925-930.<br />

4. Tolnay M, Probst A.<br />

<strong>Frontotemporal</strong> lobar<br />

degeneration. An update on<br />

clinical, pathological and genetic<br />

findings. Gerontology. Jan-Feb<br />

2001;47(1):1-8.<br />

5. Rinne JO, Laine M, Kaasinen V,<br />

Norvasuo-Heila MK, Nagren K,<br />

Helenius H. Striatal dopamine<br />

transporter and extrapyramidal<br />

symptoms in frontotemporal<br />

dementia. Neurology. May 28<br />

2002;58(10):1489-1493.<br />

6. Taylor MA, Fink M. Catatonia in<br />

psychiatric classification: a home<br />

<strong>of</strong> its own. Am J Psychiatry. Jul<br />

2003;160(7):1233-1241.<br />

7. Fink M, Taylor M. Catatonia: a<br />

separate category for DSM-IV<br />

Integrative Psychiatry.<br />

1991(7):2-10.<br />

8. Faber R. <strong>Frontotemporal</strong> lobar<br />

degeneration: a consensus on<br />

clinical diagnostic criteria.<br />

Neurology. Sep 22<br />

1999;53(5):1159.<br />

9. Mourik JC, Rosso SM,<br />

Niermeijer MF, Duivenvoorden<br />

HJ, Van Swieten JC, Tibben A.<br />

<strong>Frontotemporal</strong> dementia:<br />

behavioral symptoms and<br />

caregiver distress. Dement<br />

Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2004;18(3-<br />

4):299-306.<br />

10. Varma AR, Adams W, Lloyd JJ,<br />

et al. Diagnostic patterns <strong>of</strong><br />

regional atrophy on MRI and<br />

regional cerebral blood flow<br />

change on SPECT in young onset<br />

patients with Alzheimer's<br />

disease, frontotemporal dementia<br />

and vascular dementia. Acta<br />

Neurol Scand. Apr<br />

2002;105(4):261-269.<br />

11. Boccardi M, Laakso MP,<br />

Bresciani L, et al. <strong>The</strong> MRI<br />

pattern <strong>of</strong> frontal and temporal<br />

brain atrophy in fronto-temporal<br />

dementia. Neurobiol Aging. Jan-<br />

Feb 2003;24(1):95-103.<br />

12. Williams GB, Nestor PJ, Hodges<br />

JR. Neural correlates <strong>of</strong> semantic<br />

_________________________________<br />

<strong>McLean</strong> Annals <strong>of</strong> Behavioral Neurology<br />

9

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Differentiation</strong> <strong>of</strong> Catatonia from <strong>Frontotemporal</strong><br />

<strong>Dementia</strong> in a 43-Year-Old Woman<br />

J Kagan et al.<br />

and behavioural deficits in<br />

frontotemporal dementia.<br />

Neuroimage. Feb 15<br />

2005;24(4):1042-1051.<br />

13. Snowden JS, Neary D, Mann<br />

DM. <strong>Frontotemporal</strong> dementia.<br />

Br J Psychiatry. Feb<br />

2002;180:140-143.<br />

14. Semkovska M, Bedard MA, Stip<br />

E. [Hyp<strong>of</strong>rontality and negative<br />

symptoms in schizophrenia:<br />

synthesis <strong>of</strong> anatomic and<br />

neuropsychological knowledge<br />

and ecological perspectives].<br />

Encephale. Sep-Oct<br />

2001;27(5):405-415.<br />

15. North<strong>of</strong>f G, Steinke R, Nagel<br />

DC, et al. Right lower prefrontoparietal<br />

cortical dysfunction in<br />

akinetic catatonia: a combined<br />

study <strong>of</strong> neuropsychology and<br />

regional cerebral blood flow.<br />

Psychol Med. May<br />

2000;30(3):583-596.<br />

16. American Psychiatric<br />

Association. Diagnostic and<br />

Statistical Manual <strong>of</strong> Mental<br />

Disorders, 4th edition, Text<br />

Revision. Washington, DC:<br />

American Psychiatric<br />

Association; 2000.<br />

17. Ishii K, Sakamoto S, Sasaki M,<br />

et al. Cerebral glucose<br />

metabolism in patients with<br />

frontotemporal dementia. J Nucl<br />

Med. Nov 1998;39(11):1875-<br />

1878.<br />

18. Jeong Y, Cho SS, Park JM, et al.<br />

18F-FDG PET findings in<br />

frontotemporal dementia: an<br />

SPM analysis <strong>of</strong> 29 patients. J<br />

Nucl Med. Feb 2005;46(2):233-<br />

239.<br />

19. Lauer M, Schirrmeister H,<br />

Gerhard A, et al. Disturbed<br />

neural circuits in a subtype <strong>of</strong><br />

chronic catatonic schizophrenia<br />

demonstrated by F-18-FDG-PET<br />

and F-18-DOPA-PET. J Neural<br />

Transm. 2001;108(6):661-670.<br />

20. Hodges JR, Davies R, Xuereb J,<br />

Kril J, Halliday G. Survival in<br />

frontotemporal dementia.<br />

Neurology. Aug 12<br />

2003;61(3):349-354.<br />

21. Rohland BM, Carroll BT, Jacoby<br />

RG. ECT in the treatment <strong>of</strong> the<br />

catatonic syndrome. J Affect<br />

Disord. Dec 1993;29(4):255-261.<br />

22. Bush G, Fink M, Petrides G,<br />

Dowling F, Francis A. Catatonia.<br />

II. Treatment with lorazepam and<br />

electroconvulsive therapy. Acta<br />

Psychiatr Scand. Feb<br />

1996;93(2):137-143.<br />

_________________________________<br />

<strong>McLean</strong> Annals <strong>of</strong> Behavioral Neurology<br />

10