Verbyla, D.. 2008 The greening and browning of Alaska based on ...

Verbyla, D.. 2008 The greening and browning of Alaska based on ...

Verbyla, D.. 2008 The greening and browning of Alaska based on ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Global Ecology <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Biogeography, (Global Ecol. Biogeogr.) (<str<strong>on</strong>g>2008</str<strong>on</strong>g>) 17, 547–555<br />

Blackwell Publishing Ltd<br />

RESEARCH<br />

PAPER<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>greening</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>browning</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>based</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> 1982–2003 satellite data<br />

David <str<strong>on</strong>g>Verbyla</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Department <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Forest Sciences, University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g>, Fairbanks, AK 99775, USA<br />

ABSTRACT<br />

Aim To examine the trends <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 1982–2003 satellite-derived normalized difference<br />

vegetati<strong>on</strong> index (NDVI) values at several spatial scales within tundra <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> boreal<br />

forest areas <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g>.<br />

Locati<strong>on</strong> Arctic <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> subarctic <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g>.<br />

Methods Annual maximum NDVI data from the twice m<strong>on</strong>thly Global Inventory<br />

Modelling <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Mapping Studies (GIMMS) NDVI 1982–2003 data set with 64-km 2<br />

pixels were extracted from a spatial hierarchy including three large regi<strong>on</strong>s: ecoregi<strong>on</strong><br />

polyg<strong>on</strong>s within regi<strong>on</strong>s, ecoz<strong>on</strong>e polyg<strong>on</strong>s within boreal ecoregi<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 100-km<br />

climate stati<strong>on</strong> buffers. <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> 1982–2003 trends <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> mean annual maximum NDVI<br />

values within each area, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> within individual pixels, were computed using simple<br />

linear regressi<strong>on</strong>. <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> relati<strong>on</strong>ship between NDVI <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> temperature <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> precipitati<strong>on</strong><br />

was investigated within climate stati<strong>on</strong> buffers.<br />

Results At the largest spatial scale <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> polar, boreal <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> maritime regi<strong>on</strong>s, the str<strong>on</strong>gest<br />

trend was a negative trend in NDVI within the boreal regi<strong>on</strong>. At a finer scale <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

ecoregi<strong>on</strong> polyg<strong>on</strong>s, there was a str<strong>on</strong>g positive NDVI trend in cold arctic tundra<br />

areas, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> a str<strong>on</strong>g negative trend in interior boreal forest areas. Within boreal ecoz<strong>on</strong>e<br />

polyg<strong>on</strong>s, the weakest negative trends were from areas with a maritime climate or<br />

colder mountainous ecoz<strong>on</strong>es, while the str<strong>on</strong>gest negative trends were from warmer<br />

basin ecoz<strong>on</strong>es. <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> trends from climate stati<strong>on</strong> buffers were similar to ecoregi<strong>on</strong><br />

trends, with no significant trends from Bering tundra buffers, significant increasing<br />

trends am<strong>on</strong>g arctic tundra buffers <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> significant decreasing trends am<strong>on</strong>g interior<br />

boreal forest buffers. <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> interannual variability <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> NDVI am<strong>on</strong>g the arctic tundra<br />

buffers was related to the previous summer warmth index. <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> spatial pattern <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

increasing tundra NDVI at the pixel level was related to the west-to-east spatial pattern<br />

in changing climate across arctic <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g>. <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g>re was no significant relati<strong>on</strong>ship between<br />

interannual NDVI <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> precipitati<strong>on</strong> or temperature am<strong>on</strong>g the boreal forest buffers.<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> decreasing NDVI trend in interior boreal forests may be due to several factors<br />

including increased insect/disease infestati<strong>on</strong>s, reduced photosynthesis <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> a change in<br />

root/leaf carb<strong>on</strong> allocati<strong>on</strong> in resp<strong>on</strong>se to warmer <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> drier growing seas<strong>on</strong> climate.<br />

Corresp<strong>on</strong>dence: David <str<strong>on</strong>g>Verbyla</str<strong>on</strong>g>, Department<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Forest Sciences, University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g>,<br />

Fairbanks, AK 99775, USA.<br />

E-mail: D.<str<strong>on</strong>g>Verbyla</str<strong>on</strong>g>@uaf.edu<br />

Main c<strong>on</strong>clusi<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g>re was a c<strong>on</strong>trast in trends <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 1982–2003 annual maximum<br />

NDVI, with cold arctic tundra significantly increasing in NDVI <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> relatively warm<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> dry interior boreal forest areas c<strong>on</strong>sistently decreasing in NDVI. <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> annual<br />

maximum NDVI from arctic tundra areas was str<strong>on</strong>gly related to a summer warmth<br />

index, while there were no significant relati<strong>on</strong>ships in boreal areas between annual<br />

maximum NDVI <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> precipitati<strong>on</strong> or temperature. Annual maximum NDVI was<br />

not related to spring NDVI in either arctic tundra or boreal buffers.<br />

Keywords<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g>, boreal forest, <str<strong>on</strong>g>browning</str<strong>on</strong>g>, climate warming, drought, GIMMS, <str<strong>on</strong>g>greening</str<strong>on</strong>g>,<br />

NDVI, summer warmth index, tundra.<br />

© <str<strong>on</strong>g>2008</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> Author DOI: 10.1111/j.1466-8238.<str<strong>on</strong>g>2008</str<strong>on</strong>g>.00396.x<br />

Journal compilati<strong>on</strong> © <str<strong>on</strong>g>2008</str<strong>on</strong>g> Blackwell Publishing Ltd www.blackwellpublishing.com/geb 547

D. <str<strong>on</strong>g>Verbyla</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

An increasing trend in the satellite-derived normalized difference<br />

vegetati<strong>on</strong> index (NDVI) has been reported as a ‘<str<strong>on</strong>g>greening</str<strong>on</strong>g> trend’<br />

at global (Myneni et al., 1997; Slayback et al., 2003) <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> regi<strong>on</strong>al<br />

scales (Hicke et al., 2002; Jia et al., 2003). <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> NDVI is correlated<br />

to the fracti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> photosynthetically active radiati<strong>on</strong> absorbed by<br />

plants, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> thus to photosynthetic activity. A warming climate<br />

has led to earlier soil thaw, earlier green-up <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> l<strong>on</strong>ger growing<br />

seas<strong>on</strong>s in boreal <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> tundra regi<strong>on</strong>s that may result in increased<br />

gross photosynthetic activity (Slayback et al., 2003) <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> net primary<br />

productivity (Kimball et al., 2007).<br />

At the c<strong>on</strong>tinental scale <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> North America, NDVI trends in the<br />

boreal forest regi<strong>on</strong> have been weak or negative (Goetz et al.,<br />

2005; Bunn & Goetz, 2006), while tundra regi<strong>on</strong>s have increased<br />

in NDVI with the warming climate (Bunn et al., 2005, 2007).<br />

At the circumpolar scale, Bunn & Goetz (2006) found trends from<br />

the global boreal forest to vary by seas<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> cover type, with a<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>greening</str<strong>on</strong>g> trend in areas <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> sparse tree cover while more densely<br />

forested areas experienced a <str<strong>on</strong>g>browning</str<strong>on</strong>g> trend (decreasing NDVI),<br />

especially in late summer. <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g>y hypothesized that temperatureinduced<br />

drought stress was likely to be influencing the decreasing<br />

trend in NDVI in some boreal forest areas.<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> objective <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this paper is to examine the trends <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 1982–<br />

2003 NDVI within <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> western Yuk<strong>on</strong> Territory at several<br />

spatial scales. <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> study area c<strong>on</strong>sisted <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a spatial hierarchy <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

regi<strong>on</strong>s with mean summer temperatures ranging from 4 to 10 °C<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> summer precipitati<strong>on</strong> ranging from 75 to over 200 mm (Fig. 1).<br />

Mountain ranges such as the Brooks Range in northern <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> the <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g>, Chugach <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Wrangell ranges in central <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g> act<br />

as topographic barriers influencing vegetati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> climate. Cold<br />

arctic tundra <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> warmer boreal forest are separated by the Brooks<br />

Range, while a west to east gradient <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> maritime to c<strong>on</strong>tinental<br />

climate within the boreal regi<strong>on</strong> is due to topographic barriers.<br />

METHODS<br />

Advanced Very High Resoluti<strong>on</strong> Radiometer (AVHRR) NDVI<br />

data were acquired from the NASA Global Inventory, M<strong>on</strong>itoring<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Modelling project (GIMMS-G) for the period <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 1982–2003<br />

from the University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Maryl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Global L<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Cover Facility<br />

(http://www.l<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>cover.org/). <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g>se data are available as<br />

maximum NDVI values for each 64-km 2 pixel from each 15-day<br />

composite period. By selecting the maximum NDVI during a<br />

15-day period, the n<strong>on</strong>-vegetati<strong>on</strong> effects, such as cloud or<br />

smoke c<strong>on</strong>taminati<strong>on</strong>, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> view geometry effects are reduced.<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> data are available globally <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> have been calibrated to<br />

correct for orbital drift <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> sensor degradati<strong>on</strong> from a time series<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> five satellites (1982–85, NOAA-7; 1986–88, NOAA-9; 1989–<br />

93, NOAA-11; 1995–2000, NOAA-14; 2001–03, NOAA-16). <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

data were also processed to correct for atmospheric effects<br />

resulting from two major volcanic erupti<strong>on</strong>s, El Chich<strong>on</strong> in<br />

1982, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Mount Pinatubo in 1991 (Tucker et al., 2005).<br />

In this paper, the maximum NDVI value from each year was<br />

selected for each 64 km 2 pixel. Annual maximum NDVI values<br />

can vary interannually <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> by vegetati<strong>on</strong> type. For example,<br />

Hope et al., (2003) found annual maximum NDVI to vary from<br />

1–15 July to 1–15 August at an arctic tundra site in <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g>. Thus<br />

by using annual maximum NDVI, spatial variati<strong>on</strong> within any<br />

composite period due to phenology (<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> also possible cloud<br />

c<strong>on</strong>taminati<strong>on</strong>) was minimized.<br />

In additi<strong>on</strong>, the maximum spring NDVI was extracted from<br />

each pixel to examine the relati<strong>on</strong>ship between spring NDVI <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

annual maximum NDVI. Maximum spring NDVI was extracted<br />

Figure 1 Polar, Boreal <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Maritime regi<strong>on</strong>s<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> ecoregi<strong>on</strong> polyg<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> boreal <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> arctic<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g>. Ecoregi<strong>on</strong>s: 1, Arctic Coastal Plain;<br />

2, Arctic Foothills; 3, Brooks Range; 4, Bering<br />

Tundra; 5, Western Taiga; 6, Western Interior;<br />

7, Eastern Interior; 8, <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g>–Chugach–<br />

Wrangell ranges; 9, Cook Inlet. Albers equal<br />

area map projecti<strong>on</strong> (st<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>ard parallels<br />

55° N, 65° N). (Source: Nowacki et al., 2001).<br />

© <str<strong>on</strong>g>2008</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> Author<br />

548 Global Ecology <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Biogeography, 17, 547–555, Journal compilati<strong>on</strong> © <str<strong>on</strong>g>2008</str<strong>on</strong>g> Blackwell Publishing Ltd

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g> NDVI trends<br />

Figure 2 Buffers <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> radius 100 km centred<br />

<strong>on</strong> first-order climate stati<strong>on</strong>s used in this<br />

study. Arctic tundra stati<strong>on</strong>s: Barrow,<br />

Kuparuk, Umiat. Bering tundra stati<strong>on</strong>s:<br />

Kotzebue, Nome, Bethel, King Salm<strong>on</strong>. Boreal<br />

forest stati<strong>on</strong>s: Bettles, McGrath, Fairbanks,<br />

Delta, Talkeetna, Gulkana. Only pixels within<br />

100-m elevati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> each climate stati<strong>on</strong> were<br />

used in the analysis. Albers equal area map<br />

projecti<strong>on</strong> (st<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>ard parallels 55° N, 65° N).<br />

from the period 1–15 June for arctic tundra pixels, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> the<br />

period 15–30 May for boreal forest pixels, since these composite<br />

periods corresp<strong>on</strong>d to the spring green-up period for tundra <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

boreal forest regi<strong>on</strong>s in <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g>.<br />

Simple linear regressi<strong>on</strong> was used to summarize the trend in<br />

annual maximum NDVI within each regi<strong>on</strong> during the 22-year<br />

period. A spatial hierarchy <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> ecoregi<strong>on</strong> polyg<strong>on</strong>s was used as<br />

defined by Nowacki et al. (2001). At the largest spatial scale <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

analysis, the trends within polar, boreal <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> maritime regi<strong>on</strong>s<br />

(Fig. 1) were investigated. <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> polar regi<strong>on</strong> was predominantly a<br />

tundra z<strong>on</strong>e with cold summer temperatures. <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> boreal regi<strong>on</strong><br />

was predominantly boreal forest within the rain shadow <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> major<br />

mountain ranges. <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> maritime regi<strong>on</strong> was a wet regi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

coastal areas influenced by the Pacific Ocean.<br />

Within the polar <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> boreal regi<strong>on</strong>s, a smaller scale <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> ecoregi<strong>on</strong><br />

polyg<strong>on</strong>s was used because there is a west to east gradient <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

maritime to c<strong>on</strong>tinental climate within the <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g>n boreal forest<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> a coastal temperature gradient within the polar z<strong>on</strong>e. Each<br />

ecoregi<strong>on</strong> was a polyg<strong>on</strong> defined by physiography (Table 1,<br />

Fig. 1). At a smaller scale, ecoz<strong>on</strong>e polyg<strong>on</strong>s (Nowacki et al.,<br />

2001) within the boreal ecoregi<strong>on</strong>s were also examined to further<br />

assess the effect <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the east to west climatic gradient within the<br />

boreal regi<strong>on</strong>. Areas that were burned during 1973–2003 were<br />

excluded from the analysis since wildfire is comm<strong>on</strong> within<br />

boreal <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> can influence NDVI values.<br />

First-order climate stati<strong>on</strong>s within the polar <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> boreal<br />

regi<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g> were used to investigate the interannual<br />

relati<strong>on</strong>ship between annual maximum NDVI <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> temperature/<br />

precipitati<strong>on</strong> indices. A buffer was created around the locati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

each climate stati<strong>on</strong>, as all pixels within 100 m elevati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

within 100 km <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the climate stati<strong>on</strong>. <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g>re were few climate<br />

stati<strong>on</strong>s in <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g> with records from the period 1982–2003: three<br />

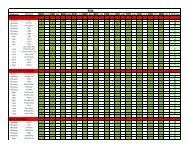

Table 1 Linear trends in annual maximum normalized difference<br />

vegetati<strong>on</strong> index (NDVI) (1982–2003) by ecoregi<strong>on</strong> (n = 22 years).<br />

Slopes represent changes in NDVI (unitless) per year (n = 22).<br />

Ecoregi<strong>on</strong> r 2 Slope P-value<br />

1. Arctic Coastal Plain 0.63 +0.005 < 0.01<br />

2. Arctic Foothills 0.52 +0.003 < 0.01<br />

3. Brooks Range 0.09 +0.0008 0.17<br />

4. Bering Tundra 0.04 –0.0008 0.37<br />

5. Western Taiga 0.17 –0.002 0.05<br />

6. Western Interior 0.38 –0.003 < 0.01<br />

7. Eastern Interior 0.53 –0.003 < 0.01<br />

8. Wrangell/<str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g> ranges 0.04 –0.0008 0.38<br />

9. Cook Inlet 0.16 –0.002 0.07<br />

stati<strong>on</strong>s from the arctic tundra regi<strong>on</strong>, four stati<strong>on</strong>s from the<br />

Bering tundra regi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> six stati<strong>on</strong>s from the interior boreal<br />

regi<strong>on</strong> (Fig. 2). Climate data for the period 1982–2003 were<br />

downloaded from the Western Regi<strong>on</strong>al Climate Center website<br />

(http://www.wrcc.dri.edu/). An annual summer warmth index<br />

(Jia et al., 2003) was computed for tundra climate stati<strong>on</strong>s as the<br />

sum <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> m<strong>on</strong>thly mean temperatures above 0 °C.<br />

Spring budburst <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> green-up typically occur in early June in<br />

tundra areas <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> early May in boreal areas <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g>. A tundra<br />

spring warmth index was computed for tundra buffers as the<br />

sum <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> m<strong>on</strong>thly mean temperatures for May plus June <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> each<br />

year. A boreal spring warmth index was computed for boreal<br />

buffers as the sum <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> m<strong>on</strong>thly mean temperatures for April plus<br />

May <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> each year.<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> finest grain size used in this study was the pixel level. <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

linear trend for each 64-km 2 pixel was computed using a linear<br />

© <str<strong>on</strong>g>2008</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> Author<br />

Global Ecology <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Biogeography, 17, 547–555, Journal compilati<strong>on</strong> © <str<strong>on</strong>g>2008</str<strong>on</strong>g> Blackwell Publishing Ltd 549

D. <str<strong>on</strong>g>Verbyla</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Table 2 Linear trends in annual maximum normalized difference vegetati<strong>on</strong> index (NDVI) (1982–2003) by ecoz<strong>on</strong>e polyg<strong>on</strong> within western<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> eastern boreal ecoregi<strong>on</strong>s. Slopes represent changes in NDVI (unitless) per year (n = 22). Mean temperature <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> precipitati<strong>on</strong> values were<br />

extracted from each ecoz<strong>on</strong>e polyg<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>based</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> climate data from Fleming et al. (2000). Climate <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> wildfire burn data were downloaded from<br />

http://agdc.usgs.gov/data/.<br />

Ecoz<strong>on</strong>e<br />

Including burns:<br />

Excluding burns:<br />

r 2 Slope P-value r 2 Slope P-value<br />

Mean May–Aug.<br />

temp. (°C)<br />

Total May–Aug.<br />

precip (mm)<br />

Davids<strong>on</strong> Mountains 0.14 –0.001 0.09 0.12 –0.001 0.11 4.2 129<br />

Kobuk Ridges <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Valleys 0.18 –0.002 0.05 0.18 –0.002 0.05 8.7 150<br />

Lower Yuk<strong>on</strong> Lowl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s 0.54 –0.004 < 0.01 0.54 –0.004 < 0.01 11.1 171<br />

Kuskokwim Upl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s 0.36 –0.003 < 0.01 0.33 –0.003 < 0.01 10.5 207<br />

Lime Hills 0.06 –0.001 0.27 0.06 –0.001 0.28 9.3 239<br />

Kuskokwim Lowl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s 0.28 –0.003 0.01 0.30 –0.003 < 0.01 10.6 192<br />

Cook Inlet 0.16 –0.002 0.06 0.16 –0.002 0.06 10.3 203<br />

Copper River Basin 0.30 –0.002 < 0.01 0.30 –0.002 < 0.01 9.2 263<br />

Tanana Lowl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s 0.51 –0.003 < 0.01 0.52 –0.003 < 0.01 11.1 196<br />

Ray Mountains 0.41 –0.003 < 0.01 0.41 –0.003 < 0.01 10.1 192<br />

Yuk<strong>on</strong>–Tanana Upl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s 0.45 –0.003 < 0.01 0.45 –0.003 < 0.01 9.3 203<br />

Yuk<strong>on</strong>–Old Crow Basin 0.52 –0.002 < 0.01 0.53 –0.002 < 0.01 8.2 108<br />

North Ogilvie Mountains 0.31 –0.002 < 0.01 0.30 –0.002 < 0.01 7.5 174<br />

regressi<strong>on</strong>. Linear trends were computed for over 28,000 pixels<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> outputted as rasters <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> P-values <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> slope from each pixel’s<br />

regressi<strong>on</strong>.<br />

RESULTS<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g>re were c<strong>on</strong>trasting linear trends from 1982–2003 between<br />

the polar <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> boreal regi<strong>on</strong>s, with the polar regi<strong>on</strong> increasing<br />

(r 2 = 0.13, slope = +0.0011, P = 0.10), <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> the boreal regi<strong>on</strong><br />

decreasing (r 2 = 0.41, slope = –0.0024, P = 0.002) in mean<br />

annual maximum NDVI. <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g>re was no significant trend in<br />

the maritime regi<strong>on</strong> (r 2 < 0.01, slope = –0.0003, P = 0.817). All<br />

regi<strong>on</strong>s had a decrease in NDVI in 1992, presumably due to the<br />

stratospheric aerosols <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> subsequent cooling resulting from the<br />

1991 Pinatubo erupti<strong>on</strong> (Lucht et al., 2002).<br />

At the ecoregi<strong>on</strong> polyg<strong>on</strong> scale, the <strong>on</strong>ly significant (P > 0.05)<br />

positive trends in mean annual maximum NDVI were from the<br />

arctic tundra ecoregi<strong>on</strong>s north <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the Brooks Range, with the<br />

str<strong>on</strong>gest trend from the Arctic Coastal Plain (Table 1). <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g>re<br />

were significant decreasing NDVI trends in boreal forest<br />

ecoregi<strong>on</strong>s, with the str<strong>on</strong>gest trend from the Eastern Interior.<br />

Trends from all other ecoregi<strong>on</strong>s were not significant (Table 1).<br />

Within smaller ecoz<strong>on</strong>e polyg<strong>on</strong>s from boreal ecoregi<strong>on</strong>s, the<br />

str<strong>on</strong>gest negative trends were from physiographic basins such as<br />

the Lower Yuk<strong>on</strong> Lowl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s, the Tanana Lowl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> the<br />

Yuk<strong>on</strong>–Old Crow Basin (Table 2). Physiographic regi<strong>on</strong>s with<br />

the weakest negative trends were from areas with a maritime<br />

climate (Lime Hills <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Cook Inlet) <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> colder mountainous<br />

regi<strong>on</strong>s (Davids<strong>on</strong> Mountains, Kobuk Ridges <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Valleys).<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> 1982–2003 trends from climate stati<strong>on</strong> buffers were similar<br />

to regi<strong>on</strong>al trends from the ecoregi<strong>on</strong> polyg<strong>on</strong> analysis. <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g>re<br />

were no significant trends (P > 0.05) in annual maximum NDVI<br />

am<strong>on</strong>g climate stati<strong>on</strong> buffers from the Bering tundra regi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

western <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g>. All arctic tundra buffers had significant positive<br />

trends <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> all boreal stati<strong>on</strong>s had significant negative trends in<br />

annual maximum NDVI (Table 3).<br />

In arctic <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g>, the interannual patterns <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> NDVI (both<br />

annual maximum <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 1–15 June maximum NDVI) from the<br />

climate stati<strong>on</strong> buffers were str<strong>on</strong>gly correlated (Pears<strong>on</strong>’s<br />

r > 0.80) with the interannual patterns NDVI from the Arctic<br />

Coastal Plain ecoregi<strong>on</strong>. If the interannual NDVI from buffers<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> the ecoregi<strong>on</strong> were not str<strong>on</strong>gly correlated, then local factors<br />

such as variable cloud cover or differing disturbances am<strong>on</strong>g<br />

climate stati<strong>on</strong> might dominate the NDVI trend relative to the<br />

ecoregi<strong>on</strong> NDVI trend.<br />

Over the 22-year period, the most rapid increase in NDVI in<br />

arctic tundra areas occurred during the 1–15 June composite<br />

period, probably due to snowmelt, budburst <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> leaf flush. <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

1–15 June maximum NDVI within each climate stati<strong>on</strong> buffer<br />

was related to the tundra spring warmth index from each climate<br />

stati<strong>on</strong> (r 2 ranging from 0.33 to 0.66, P < 0.01). However, the<br />

relati<strong>on</strong>ship between 1–15 June maximum NDVI <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> annual<br />

maximum NDVI was weak <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> not significant (r 2 ranging from<br />

0.05 to 0.03, P > 0.33), indicating that early growing seas<strong>on</strong> c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s<br />

may not c<strong>on</strong>trol annual maximum NDVI in the <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g>n<br />

arctic tundra.<br />

Jia et al. (2003) reported a significant linear relati<strong>on</strong>ship in<br />

arctic <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g> between maximum NDVI <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> a summer warmth<br />

index, expressed as the sum <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> m<strong>on</strong>thly mean temperatures<br />

above 0 °C. In this study, there was also a significant linear<br />

relati<strong>on</strong>ship (P < 0.01, r 2 = 0.58) between annual maximum<br />

NDVI <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> summer warmth index. However, the relati<strong>on</strong>ship<br />

between annual maximum NDVI values <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> the previous<br />

year’s summer warmth index values was str<strong>on</strong>ger (P < 0.01,<br />

r 2 = 0.66).<br />

Am<strong>on</strong>g boreal climate stati<strong>on</strong> buffers, the early spring NDVI<br />

(1–15 May) was linearly related to the boreal spring warmth<br />

index (r 2 ranging from 0.48 to 0.58, P < 0.01). <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g>re were no<br />

© <str<strong>on</strong>g>2008</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> Author<br />

550 Global Ecology <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Biogeography, 17, 547–555, Journal compilati<strong>on</strong> © <str<strong>on</strong>g>2008</str<strong>on</strong>g> Blackwell Publishing Ltd

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g> NDVI trends<br />

Table 3 Linear trend in annual maximum normalized difference vegetati<strong>on</strong> index (NDVI) (1982–2003) within climate stati<strong>on</strong> 100-km buffers.<br />

Slopes represent changes in NDVI (unitless) per year (n = 22).<br />

Climate stati<strong>on</strong> r 2 Slope P-value No. <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> pixels<br />

Mean May–Aug.<br />

temp. ( o C)<br />

Mean annual<br />

precipitati<strong>on</strong> (mm)<br />

Bering tundra regi<strong>on</strong><br />

Bethel 0.09 –0.002 0.16 455 10 453<br />

Kotzebue 0.007 0.0003 0.72 219 8 282<br />

Nome 0.01 +0.0005 0.59 145 8 438<br />

King Salm<strong>on</strong> 0.01 –0.0005 0.63 291 11 497<br />

Arctic tundra regi<strong>on</strong><br />

Barrow 0.56 +0.005 < 0.01 419 1 111<br />

Kuparuk 0.65 +0.005 < 0.01 235 3 97<br />

Umiat 0.55 +0.004 < 0.01 278 6 126<br />

Boreal forest regi<strong>on</strong><br />

Bettles 0.33 –0.002 < 0.01 122 12 380<br />

Delta 0.67 –0.004 < 0.01 118 13 309<br />

Fairbanks 0.46 –0.003 < 0.01 180 14 278<br />

Gulkana 0.30 –0.002 < 0.01 49 11 294<br />

McGrath 0.43 –0.004 < 0.01 185 12 465<br />

Talkeetna 0.19 –0.002 0.04 131 13 738<br />

significant (P > 0.16) linear relati<strong>on</strong>ships between annual<br />

maximum NDVI as a functi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> early spring NDVI for boreal<br />

buffers (r 2 ranging from < 0.01 to 0.09) Unlike the arctic tundra<br />

stati<strong>on</strong>s, there were no significant linear relati<strong>on</strong>ships between<br />

annual maximum NDVI <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> current or lagged summer warmth<br />

index values (P > 0.30, r 2 < 0.10).<br />

Bunn et al. (2005) found that the previous spring minimum<br />

temperature was an important variable in predicting summer<br />

NDVI in c<strong>on</strong>iferous <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> broadleaf boreal areas <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Canada. In this<br />

study, the linear relati<strong>on</strong>ships <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> annual maximum NDVI as a<br />

functi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> previous spring temperature were weak (r 2 ranging<br />

from < 0.01 to 0.22). <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> linear relati<strong>on</strong>ships <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> annual maximum<br />

NDVI as a functi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> August through July precipitati<strong>on</strong> were<br />

also weak (r 2 ranging from 0.06 to 0.24).<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> 1982–2003 pattern <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> an increasing NDVI trend in<br />

northern arctic <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> a decreasing trend in interior <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

also was evident from the pixel-level linear regressi<strong>on</strong>s. <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

highest rate <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> increase occurred al<strong>on</strong>g the central <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> eastern<br />

Arctic coastal plain, while the highest rate <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> decrease occurred in<br />

basins <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> interior <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g> (Fig. 3).<br />

DISCUSSION<br />

NDVI trends across the <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g>n tundra<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> growing seas<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the Arctic is now at its warmest relative to<br />

at least the past 400 years (Overpeck et al., 1997). Arctic <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g> is<br />

undergoing a system-wide resp<strong>on</strong>se to an altered climatic state<br />

(Hinzman et al., 2005). <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> summer warming in arctic <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

may be due to a lengthening <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the snow-free seas<strong>on</strong>, with early<br />

sensible heating <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the lower atmosphere (Chapin et al., 2005).<br />

Vegetati<strong>on</strong> resp<strong>on</strong>ses have included delayed senescence (March<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

et al., 2004) <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> increased broadleaf shrub abundance across the<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g>n arctic tundra (Sturm et al., 2001; Tape et al., 2006). <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

increase in annual maximum NDVI may be due to an increase<br />

in height <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> cover <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> shrubs <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> graminoids (Walker et al.,<br />

2006).<br />

Within the arctic climate stati<strong>on</strong> buffers there was a significant<br />

linear relati<strong>on</strong>ship between annual maximum NDVI <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> annual<br />

summer warmth index values, c<strong>on</strong>sistent with the results <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

March<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> et al. (2004), who found infrared heating <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> tundra<br />

plots significantly increased NDVI within a few weeks <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> heating.<br />

A str<strong>on</strong>ger linear relati<strong>on</strong>ship was observed between annual<br />

maximum NDVI <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> the previous year’s summer warmth index.<br />

For example, the highest summer warmth index at Barrow,<br />

Kuparuk <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Umiat occurred in 1989 <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> the highest residual<br />

from the NDVI trend lines occurred the next year. Spring greenup,<br />

expressed as maximum NDVI from the 1–15 June composite<br />

period, was a poor predictor <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> annual maximum NDVI at the<br />

climate stati<strong>on</strong> buffer scale <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> at the ecoregi<strong>on</strong> scale. Thus it<br />

appears that annual maximum NDVI was not dependent <strong>on</strong><br />

whether spring was early or late for any given year.<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g>re were significant positive temporal trends in NDVI from<br />

1982 to 2003 at all spatial scales examined in the arctic tundra<br />

regi<strong>on</strong>. However, there were no significant temporal trends in<br />

NDVI at any spatial scale in the shrub tundra regi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> western<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g>. This may be due to the much colder climate <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the arctic<br />

ecoregi<strong>on</strong>s relative to the Bering tundra ecoregi<strong>on</strong> (Table 3), with<br />

warming occurring at a faster rate in the arctic regi<strong>on</strong>. In general,<br />

there has been less warming <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> drying in western <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g> relative<br />

to central <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> eastern arctic <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g>, which has been described as<br />

a steepened gradient in c<strong>on</strong>tinentality over the past 20 years<br />

(Thomps<strong>on</strong> et al., 2006). <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> pattern <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> increasing NDVI over<br />

the period 1982–2003 in tundra regi<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g> followed this<br />

west–east trend, with the northern arctic trend str<strong>on</strong>gest east <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

160° W l<strong>on</strong>gitude (Fig. 3).<br />

© <str<strong>on</strong>g>2008</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> Author<br />

Global Ecology <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Biogeography, 17, 547–555, Journal compilati<strong>on</strong> © <str<strong>on</strong>g>2008</str<strong>on</strong>g> Blackwell Publishing Ltd 551

D. <str<strong>on</strong>g>Verbyla</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Figure 3 Linear trends in annual (1982–2003) maximum normalized difference vegetati<strong>on</strong> index (NDVI) values for each 64-km 2 pixel in the<br />

study regi<strong>on</strong>. Only pixels with significant (P < 0.05) linear regressi<strong>on</strong> slopes are displayed. Albers equal area map projecti<strong>on</strong> (st<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>ard parallels<br />

55° N, 65° N).<br />

NDVI trends across the <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g>n boreal forest<br />

Starting around 1976, the climate <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> boreal <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g> shifted to a<br />

regime with warmer winter <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> summer temperatures (Hartman<br />

& Wendler, 2005). <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> shift in climate regime coincided with a<br />

shift in the phase <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the Pacific Decadal Oscillati<strong>on</strong> (Mantua<br />

et al., 1997). Based <strong>on</strong> analyses <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Fairbanks tree rings <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> carb<strong>on</strong><br />

isotope data, the warmest summers in the past 200 years have<br />

occurred in the period since the mid-1970s (Barber et al., 2004).<br />

With warmer temperatures <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> no significant trend in precipitati<strong>on</strong>,<br />

an increase in potential evapotranspirati<strong>on</strong> has occurred in<br />

boreal <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g> (Riordan et al., 2006). Decreases in NDVI in boreal<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g> may be associated with several factors, including tree<br />

drought stress <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> mortality, wildfire dynamics, insect <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

disease infestati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> changes in leaf/root allocati<strong>on</strong>.<br />

In boreal <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g>, shrinking p<strong>on</strong>ds have occurred due to<br />

increased drainage associated with warming permafrost<br />

(Yoshikawa & Hinzman, 2003) <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> increased evaporati<strong>on</strong> (Klein<br />

et al., 2005). Analysis <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> tree rings has dem<strong>on</strong>strated reduced<br />

growth associated with climate warming <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> attributed to<br />

drought stress (Barber et al., 2000). <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> declining trend <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> NDVI<br />

may be due to a reducti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> photosynthesis during soil moisture<br />

deficits (Angert et al., 2005, Ueyama et al., 2006), although the<br />

resp<strong>on</strong>se may lag by several years <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> drought <strong>on</strong> wet black spruce<br />

sites (Kljun et al., 2006). A l<strong>on</strong>ger-term resp<strong>on</strong>se that also would lead<br />

to declining NDVI is a change in carb<strong>on</strong> allocati<strong>on</strong> in resp<strong>on</strong>se to<br />

drier c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s with decreasing foliage producti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> increasing<br />

root producti<strong>on</strong> (Runy<strong>on</strong> et al., 1994, Lapenis et al., 2005).<br />

Although wildfire is the major large-scale disturbance agent in<br />

boreal <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g>, the area burned between 1973 <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 2003 was a<br />

small proporti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> any ecoregi<strong>on</strong> polyg<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> excluding<br />

burned areas from the analysis did not substantially affect the<br />

trends (Table 2). However, at a pixel level (Fig. 3), two <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the<br />

hotspots <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> str<strong>on</strong>gest decline in 1982–2003 NDVI were from<br />

areas that burned during this period in boreal <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g>.<br />

Climate warming in boreal <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g> has resulted in increased<br />

tree <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> shrub mortality from insects <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> disease (Soja et al.,<br />

2007), with some insect species shortening their life cycle by half<br />

(Berg et al., 2006). Over the past 20 years, there have been<br />

substantial increases in insects <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>/or diseases infesting<br />

hundreds <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> thous<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> hectares <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> shrubl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> forests in<br />

boreal <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g> including spruce budworm <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> spruce bark beetle<br />

in white spruce (Malmstrom & Raffa, 2000; Berg et al., 2006),<br />

larch sawfly (Malmstrom & Raffa, 2000), leafblotch miner in<br />

willows (Furniss et al., 2001), aspen leaf miner (Doak et al.,<br />

2007), birch leaf mining sawflies (Snyder et al., 2007) <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> alder<br />

© <str<strong>on</strong>g>2008</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> Author<br />

552 Global Ecology <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Biogeography, 17, 547–555, Journal compilati<strong>on</strong> © <str<strong>on</strong>g>2008</str<strong>on</strong>g> Blackwell Publishing Ltd

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g> NDVI trends<br />

woolly sawfly/stem cankers in alders (Ruess et al., 2006). <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> area<br />

affected by insect <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> disease infestati<strong>on</strong>s exceeds wildfire in<br />

boreal <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g> (Malmstrom & Raffa, 2000) <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> would probably<br />

cause a decrease in NDVI.<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> lack <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> simple correlati<strong>on</strong>s between interannual maximum<br />

NDVI <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> precipitati<strong>on</strong> am<strong>on</strong>g boreal climate stati<strong>on</strong> buffers is<br />

not surprising. Spatial variati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> precipitati<strong>on</strong> is high relative<br />

to temperature (Simps<strong>on</strong> et al., 2002). For example, the Fairbanks<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Delta climate stati<strong>on</strong>s both occur <strong>on</strong> the Tanana River<br />

floodplain with overlapping 100-km climate buffers (Fig. 2),<br />

have str<strong>on</strong>gly correlated annual maximum NDVI values (Pears<strong>on</strong>’s<br />

r = 0.91, 1982–2003), <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> mean m<strong>on</strong>thly temperature (Pears<strong>on</strong>’s<br />

r = 0.99, 1982–2003). However, the correlati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> m<strong>on</strong>thly total<br />

precipitati<strong>on</strong> between these two stati<strong>on</strong>s is substantially lower<br />

(Pears<strong>on</strong>’s r = 0.61, 1982–2003), <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> the actual mean precipitati<strong>on</strong><br />

within 100 km <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> each climate buffer is likely to vary<br />

substantially relative to precipitati<strong>on</strong> at a climate stati<strong>on</strong>.<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> short-term resp<strong>on</strong>se <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> boreal trees to precipitati<strong>on</strong> may<br />

also be species- <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> site-specific. For example, Yarie & Van Cleve<br />

(2006) found reduced diameter growth <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> floodplain white<br />

spruce <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> balsam poplar trees, but not in most upl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> species<br />

in a rain-exclusi<strong>on</strong> experiment. Barr et al. (2004) found a decline<br />

in aspen maximum leaf area index during a 4-year drought, but<br />

no c<strong>on</strong>comitant decline from understorey hazelnut canopies.<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> l<strong>on</strong>g-term decreasing trend in NDVI in boreal <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g> is in<br />

c<strong>on</strong>trast to an increasing trend in the boreal forest <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the<br />

Komi Republic <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> north-west Russia (Lopatin et al., 2006). Both<br />

regi<strong>on</strong>s have experienced warming since the early 1980s.<br />

However, much <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> boreal <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g> is semi-arid with potential<br />

evapotranspirati<strong>on</strong> exceeding precipitati<strong>on</strong> (Barber et al., 2000;<br />

Gower et al., 2001), while precipitati<strong>on</strong> exceeds potential<br />

evapotranspirati<strong>on</strong> in the Komi Republic (Lopatin et al., 2006).<br />

In this study, the NDVI regressi<strong>on</strong> slopes were most negative <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

the R 2 values were greatest from the warmest <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> driest boreal<br />

ecoz<strong>on</strong>es (Table 2). <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> str<strong>on</strong>gest negative trends am<strong>on</strong>g boreal<br />

climate stati<strong>on</strong> buffers were also from relatively warm/dry areas<br />

with an annual precipitati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> less than 500 mm <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> mean<br />

summer temperature above 12 °C (Table 3).<br />

Although the GIMMS-NDVI data have been corrected for<br />

major volcanic erupti<strong>on</strong>s, sensor calibrati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> orbital drift<br />

over time, c<strong>on</strong>founding factors leading to residual error are<br />

possible, including reducti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> NDVI due to cloud <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> cloud<br />

shadow, extreme viewing angles, low solar elevati<strong>on</strong> early or late<br />

in the growing seas<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> atmospheric effects. <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> strategy <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

selecting the maximum NDVI during a composite period lessens<br />

the effect <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> these c<strong>on</strong>founding factors, but does not completely<br />

eliminate these problems. However, the NDVI trends in this<br />

study c<strong>on</strong>sistently occurred at a variety <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> spatial scales. For<br />

example, cold artic tundra had significant increasing trends in<br />

annual maximum NDVI at the ecoregi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 100-km buffer<br />

scale, while warmer shrub tundra from western <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g> had no<br />

significant trends at these spatial scales. Boreal forest had significant<br />

decreasing trends at all spatial scales examined <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> the<br />

trends were c<strong>on</strong>sistently str<strong>on</strong>gest in the eastern interior where<br />

growing seas<strong>on</strong>s are the warmest <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> driest relative to other areas<br />

in this study.<br />

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS<br />

I thank Scott Goetz, Martha Raynolds, John Yarie <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> the<br />

an<strong>on</strong>ymous referees for their useful suggesti<strong>on</strong>s that helped<br />

improved the manuscript. This research was supported by the<br />

B<strong>on</strong>anza Creek LTER (L<strong>on</strong>g-Term Ecological Research) program<br />

(funded jointly by NSF grant DEB-0423442 <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> USDA Forest<br />

Service, Pacific Northwest Research Stati<strong>on</strong> grant PNW01-<br />

JV11261952-231).<br />

REFERENCES<br />

Angert, A., Biraud, S., B<strong>on</strong>fils, C., Henning, C.C., Buermann, W.,<br />

Pinz<strong>on</strong>, J., Tucker, C.J. & Fung, I. (2005) Drier summers cancel<br />

out the CO 2 uptake enhancement induced by warmer springs.<br />

Proceedings <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the Nati<strong>on</strong>al Academy <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Sciences USA, 102,<br />

10823–10827.<br />

Barber, V.G., Juday, G.P. & Finney, B.P. (2000) Reduced growth<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g>n white spruce in the twentieth century from<br />

temperature-induced drought stress. Nature, 405, 668–<br />

673.<br />

Barber, V.G., Juday, G.P., Finney, B.P. & Wilmking, M. (2004)<br />

Rec<strong>on</strong>structi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> summer temperatures in interior <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

from tree-ring proxies: Evidence for changing climate regimes.<br />

Climatic Change, 63, 91–120.<br />

Barr, A.G., Black, T.A., Hogg, E.H., Kljun, N., Morgenstern, K. &<br />

Nesic, Z. (2004) Inter-annual variability in the leaf area index<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a boreal aspen-hazelnut forest in relati<strong>on</strong> to net ecosystem<br />

producti<strong>on</strong>. Agricultural <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Forest Meteorology, 126, 237–255.<br />

Berg, E., Henry, J.D., Fastie, C.L., De Volder, A.D. & Matsuoka, S.M.<br />

(2006) Spruce beetle outbreaks <strong>on</strong> the Kenai Peninsula, <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Kluane Nati<strong>on</strong>al Park <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Reserve, Yuk<strong>on</strong> Territory:<br />

relati<strong>on</strong>ship to summer temperatures <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> regi<strong>on</strong>al differences<br />

in disturbance regimes. Forest Ecology <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Management, 227,<br />

219–232.<br />

Bunn, A.G. & Goetz, S.J. (2006) Trends in satellite-observed<br />

circumpolar photosynthetic activity from 1982 to 2003: the<br />

influence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> seas<strong>on</strong>ality, cover type <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> vegetati<strong>on</strong> density.<br />

Earth Interacti<strong>on</strong>s, 10, 1–19.<br />

Bunn, A.G., Goetz, S.J. & Fiske, G.J. (2005) Observed <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

predicted resp<strong>on</strong>ses <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> plant growth to climate across Canada.<br />

Geophysical Research Letters, 32, L16710, doi:10.1029/<br />

2005GL023646.<br />

Bunn, A.G., Goetz, S.J., Kimball, J.S. & Zhang, K. (2007) Northern<br />

high-latitude ecosystems resp<strong>on</strong>d to climate change. EOS,<br />

Transacti<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the American Geophysical Uni<strong>on</strong>, 88, 333–340.<br />

Chapin, F.S. III, Sturm, M., Serreze, M.C., McFadden, J.P.,<br />

Key, J.R., Lloyd, A.H., McGuire, A.D., Rupp, T.S., Lynch, A.H.,<br />

Schimel, J.P., Beringer, J., Chapman, W.L., Epstein, H.E.,<br />

Euskirchen, E.S., Hinzman, L.D., Jia., G., Ping, C.L., Tape, K.D.,<br />

Thomps<strong>on</strong>, C.D., Walker, D.A. & Welker., J.M. (2005) Role <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

l<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>-surface changes in arctic summer warming. Science, 310,<br />

657–660.<br />

Doak, P., Wagner, D. & Wats<strong>on</strong>, A. (2007) Variable extrafloral<br />

nectary expressi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> its c<strong>on</strong>sequences in quaking aspen.<br />

Canadian Journal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Botany, 85, 1–9.<br />

© <str<strong>on</strong>g>2008</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> Author<br />

Global Ecology <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Biogeography, 17, 547–555, Journal compilati<strong>on</strong> © <str<strong>on</strong>g>2008</str<strong>on</strong>g> Blackwell Publishing Ltd 553

D. <str<strong>on</strong>g>Verbyla</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Fleming, M.D., Chapin, F.S. III, Cramer, W., Hufford, G.L. &<br />

Serreze, M.C. (2000) Geographic patterns <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> dynamics <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g>n climate interpolated from a sparse stati<strong>on</strong> record.<br />

Global Change Biology, 6(Suppl. 1), 49–58.<br />

Furniss, M.M., Holsten, E.H., Foote, M.J. & Bertram, M. (2001)<br />

Biology <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a willow leafblotch miner, Micrurapteryx salicifoliella<br />

in <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g>. Envir<strong>on</strong>mental Entomology, 30, 736–741.<br />

Goetz, S.J, Bunn, A.G., Fiske, G.J. & Hought<strong>on</strong>, R.A. (2005)<br />

Satellite-observed photosynthetic trends across boreal North<br />

America associated with climate <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> fire disturbance.<br />

Proceedings <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the Nati<strong>on</strong>al Academy <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Sciences USA, 102,<br />

13521–13525.<br />

Gower, S.T., Krankina, O., Ols<strong>on</strong>, R.J., Apps, M., Linder, S. &<br />

Wang, C. (2001) Net primary producti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> carb<strong>on</strong> allocati<strong>on</strong><br />

patterns <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> boreal forest ecosystems. Ecological Applicati<strong>on</strong>s,<br />

11, 1395–1411.<br />

Hartman, B. & Wendler, G. (2005) <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> significance <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the 1976<br />

Pacific Climate Shift in the climatology <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g>. Journal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Climate, 18, 4824–4839.<br />

Hicke, J.A., Asner, G.P., R<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>ers<strong>on</strong>, J.T., Tucker, C., Los, S.,<br />

Birdsey, R., Jenkins, J.C. & Field, C. (2002) Trends in North<br />

American net primary productivity derived from satellite<br />

observati<strong>on</strong>s, 1982–1998. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 16,<br />

1018, doi: 10.1029/2001GB001550.<br />

Hinzman, L.D., Bettez, N.D., Bolt<strong>on</strong>, W.R., Chapin, F.S. III,<br />

Dyurgerov, M.B., Fastie, C.L., Griffith, B., Hollister, R.D.,<br />

Hope, A., Huntingt<strong>on</strong>, H.P., Jensen, A.M., Jia, G.J., JorGens<strong>on</strong>,<br />

T. Kane, D.L., Klein, D.R, K<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>inas, G., Lynch, A.H., Lloyd,<br />

A.H., McGuire, A.D., Nels<strong>on</strong>, F.E., Oechel, W.C., Osterkamp,<br />

T.E., Racine, C.H., Romanovsky, V.E., St<strong>on</strong>e, R.S., Stow, D.A.,<br />

Sturm, M., Tweedie, C.E., Vourlitis, G.L., Walker, M.D.,<br />

Walker, D.A., Webber, P.J., Welker, J.M., Winker, K.S. &<br />

Yoshikawa, K. (2005) Evidence <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> implicati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> recent<br />

climate change in northern <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> other arctic regi<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

Climatic Change, 72, 251–298.<br />

Hope, A.S., Boynt<strong>on</strong>, W.L., Stow, D.A. & Douglas, D.C. (2003)<br />

Interannual growth dynamics <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> vegetati<strong>on</strong> in the Kuparuk<br />

River watershed, <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>based</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> the normalized difference<br />

vegetati<strong>on</strong> index. Internati<strong>on</strong>al Journal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Remote Sensing, 24,<br />

3413–3425.<br />

Jia, G., Epstein, H.E. & Walker D.A. (2003) Greening <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> arctic<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g>, 1981–2001. Geophysical Research Letters, 30, 2067,<br />

doi:10.1029/2003GL018268.<br />

Kimball, J.S., Zhao, M., McGuire, A.D., Heinsch, F.A., Clein, J.,<br />

Calef, M., Jolly, W.M., Kang, S.M., Euskirchen S.E., McD<strong>on</strong>ald,<br />

K.C. & Running, S.W. (2007) Recent climate-driven increases<br />

in vegetati<strong>on</strong> productivity for the western arctic: evidence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

an accelerati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the northern terrestrial carb<strong>on</strong> cycle. Earth<br />

Interacti<strong>on</strong>s, 11, 1–30.<br />

Klein, E.E., Berg, E. & Dial. R. (2005) Wetl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> drying <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> successi<strong>on</strong><br />

across the Kenai Peninsula Lowl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s, south-central <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g>.<br />

Canadian Journal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Forest Research, 35, 1931–1941.<br />

Kljun, N., Black, T.A., Griffis, T.J., Barr, A.G., Gaum<strong>on</strong>t-Guay, D.,<br />

Morgenstern, K., McCaughey, J.H. & Nesic, Z. (2006)<br />

Resp<strong>on</strong>se <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> net ecosystem productivity in three boreal forest<br />

st<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s to drought. Ecosystems, 9, 1128–1144.<br />

Lapenis, A., Shvidenko, A., Shepaschenko, D., Nilss<strong>on</strong>, S. &<br />

Aiyyer, A. (2005) Acclimati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Russian forests to recent<br />

changes in climate. Global Change Biology, 11, 2090–2102.<br />

Lopatin, E., Kolström, T. & Spiecker, H. (2006) Determinati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

forest growth trends in Komi Republic (northwestern Russia):<br />

combinati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> tree-ring analysis <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> remote sensing data.<br />

Boreal Envir<strong>on</strong>ment Research, 11, 341–353.<br />

Lucht, W., Prentice, I.C., Myneni, R.B., Sitch, S., Friedlingstein, P.,<br />

Cramer, W., Bousquet, P., Buermann, W. & Smith, B. (2002)<br />

Climatic c<strong>on</strong>trol <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the high-latitude vegetati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>greening</str<strong>on</strong>g> trend<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Pinatubo effect. Science, 296, 1687–1689.<br />

Malmstrom, C.M. & Raffa, K.F. (2000) Biotic disturbance agents<br />

in the boreal forest: c<strong>on</strong>siderati<strong>on</strong>s for vegetati<strong>on</strong> change<br />

models. Global Change Biology, 6(Suppl. 1), 35–48.<br />

Mantua, N.S., Hare, S.R., Zhang, Y., Wallace, J. & Francis, R.<br />

(1997) A pacific interdecadal climate oscillati<strong>on</strong> with impacts<br />

<strong>on</strong> salm<strong>on</strong> producti<strong>on</strong>. Bulletin <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the American Meteorological<br />

Society, 78, 1069–1079.<br />

March<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>, F.L., Nijs, I., Heuer, M., Mertens, S., Kockelbergh, F.,<br />

P<strong>on</strong>tailler, J., Impens, I. & Beyens, L. (2004) Climate warming<br />

postp<strong>on</strong>es senescence in high arctic tundra. Arctic <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Alpine<br />

Research, 36, 390–394.<br />

Myneni, R.B., Keeling, C.D., Tucker, C.J., Asrar, G. & Nemani, R.R.<br />

(1997) Increased plant growth in the northern high latitudes<br />

from 1981 to 1991. Nature, 386, 698–702.<br />

Nowacki, G., Spencer, P., Brock, T., Fleming, M. & Jorgens<strong>on</strong>, T.<br />

(2001) Unified ecoregi<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> neighboring territories.<br />

US Geological Survey Open-File Report 02–297. US Geological<br />

Survey, Anchorage, <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g>, USA.<br />

Overpeck, J., Hughen, K., Hardy, D., Bradley, R., Case, R.,<br />

Douglas, M., Finney, B., Gajewski, K., Jacoby, G., Jennings, A.,<br />

Lamoureux, S., Lasca, A., MacD<strong>on</strong>ald, G., Moore, J., Retelle, M.,<br />

Smith, S., Wolfe, A. & Zielinski, G. (1997) Arctic envir<strong>on</strong>mental<br />

change <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the last four centuries. Science, 278, 1251–1256.<br />

Riordan, B., <str<strong>on</strong>g>Verbyla</str<strong>on</strong>g>, D. & McGuire, A.D. (2006) Shrinking<br />

p<strong>on</strong>ds in subarctic <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>based</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> 1950–2002 remotely<br />

sensed images. Journal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Geophysical Research, 111, G4002,<br />

doi:10.1029/2005JG000150.<br />

Ruess, R.W., Anders<strong>on</strong>, M.D., Mitchell, J.S. & McFarl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>, J.W.<br />

(2006) Effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> defoliati<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> growth <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> N fixati<strong>on</strong> in Alnus<br />

tenuifolia: C<strong>on</strong>sequences for changing disturbance regimes at<br />

high latitudes. Ecoscience, 13, 404–412.<br />

Runy<strong>on</strong>, J., Waring, R.H., Goward, S.N. & Welles, J.M. (1994)<br />

Envir<strong>on</strong>mental limits <strong>on</strong> net primary producti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> light-use<br />

efficiency across the Oreg<strong>on</strong> transect. Ecological Applicati<strong>on</strong>s,<br />

4, 226–237.<br />

Simps<strong>on</strong>, J.J., Hufford, G.L., Fleming, M.D., Berg, J.S. &<br />

Asht<strong>on</strong>, J.B. (2002) L<strong>on</strong>g-term climate patterns in <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g>n<br />

surface temperature <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> precipitati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> their biological<br />

c<strong>on</strong>sequences. IEEE Transacti<strong>on</strong>s <strong>on</strong> Geoscience <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Remote<br />

Sensing, 40, 1164–1184.<br />

Slayback, D.A., Pinz<strong>on</strong>, J.E., Los, O.S. & Tucker, C.J. (2003)<br />

Northern Hemisphere photosynthetic trends 1982–1999.<br />

Global Change Biology, 9, 1–15.<br />

Snyder, C., MacQuarrie, C.J., Zogas, K., Kruse, J.J. & Hard, J.<br />

(2007) Invasive species in the last fr<strong>on</strong>tier: distributi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

© <str<strong>on</strong>g>2008</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> Author<br />

554 Global Ecology <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Biogeography, 17, 547–555, Journal compilati<strong>on</strong> © <str<strong>on</strong>g>2008</str<strong>on</strong>g> Blackwell Publishing Ltd

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g> NDVI trends<br />

phenology <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> birch leaf mining sawflies in <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g>. Journal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Forestry, 43, 113–155.<br />

Soja, A.J., Tchebakova, N.M., French, N.H.F., Flannigan, M.D.,<br />

Shugart, H.H., Stocks, B.J., Sukhinin, A.I., Parfenova, E.I.,<br />

Chapin, F.S. III & Stackhouse, P.W. Jr (2007) Climate-induced<br />

boreal forest change: predicti<strong>on</strong>s versus current observati<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

Global <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Planetary Change, 56, 274–296.<br />

Sturm, M., Racine, C. & Tape, K. (2001) Increasing shrub<br />

abundance in the Arctic. Nature, 411, 546–547.<br />

Tape, K., Sturm, M. & Racine, C. (2006) <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> evidence for shrub<br />

expansi<strong>on</strong> in northern <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> the pan-arctic. Global<br />

Change Biology, 12, 686–702.<br />

Thomps<strong>on</strong>, C.C., McGuire, A.D., Clein, J.S., Chapin, F.S. III &<br />

Beringer, J. (2006) Net carb<strong>on</strong> exchange across the arctic tundraboreal<br />

forest transiti<strong>on</strong> in <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g> 1981–2000. Mitigati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Adaptati<strong>on</strong> Strategies for Global Change, 11, 805–827.<br />

Tucker, C.J., Pinz<strong>on</strong>, J.E., Brown, M.E., Slayback, D.A., Pak, E.W.,<br />

Mah<strong>on</strong>ey, R., Vermote, E.F. & El Saleous, N. (2005) An<br />

extended AVHRR 8-km NDVI data set compatible with<br />

MODIS <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> SPOT vegetati<strong>on</strong> NDVI data. Internati<strong>on</strong>al<br />

Journal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Remote Sensing, 26, 4485–4498.<br />

Ueyama, M., Haraz<strong>on</strong>o, Y., Ohtaki, E. & Miyata, A. (2006) C<strong>on</strong>trolling<br />

factors <strong>on</strong> the interannual CO 2 budget at a subarctic<br />

black spruce forest in interior <str<strong>on</strong>g>Alaska</str<strong>on</strong>g>. Tellus B, 58, 491–<br />

501.<br />

Walker, M.D., Wahren, C.H., Hollister, R.D., Henry G.H.R.,<br />